Project Gutenberg's A Doctor of the Old School, Complete, by Ian Maclaren This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: A Doctor of the Old School, Complete Author: Ian Maclaren Release Date: November 1, 2006 [EBook #9320] Last Updated: March 1, 2018 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A DOCTOR OF THE OLD SCHOOL, *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Widger and PG Distributed Proofreaders

[A click on the face of any illustration

will enlarge it to full

size.]

DR. MacLURE

BOOK I. A GENERAL PRACTITIONER

Sandy Stewart “Napped” Stones

The Gudewife is Keepin' up a Ding-Dong

His House—little more than a cottage

Whirling Past in a Cloud of Dust

Will He Never Come?

The

Verra Look o' Him wes Victory

Weeping by

Her Man's Bedside

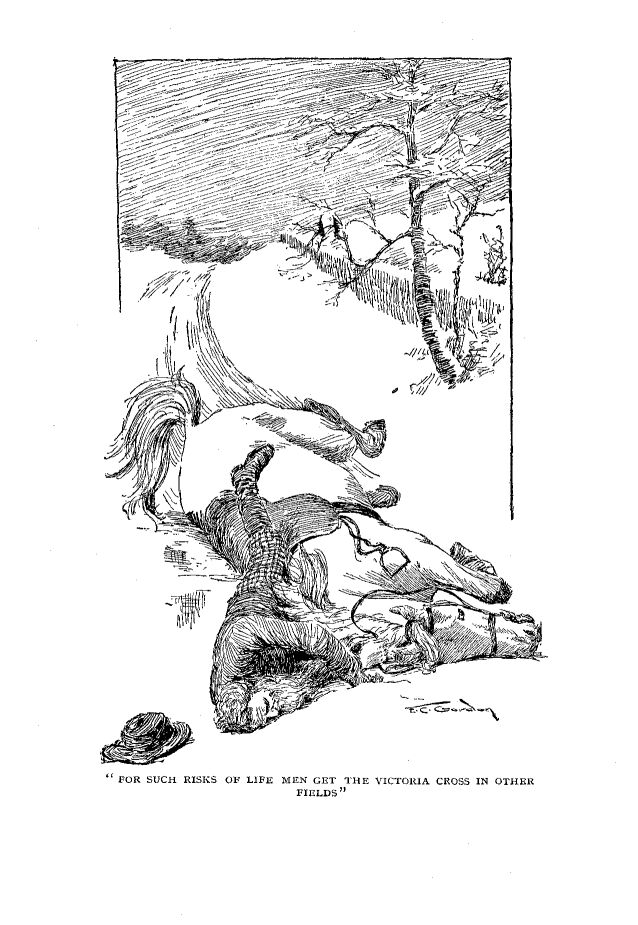

Men Get the Victoria

Cross in Other Fields

Hopps' Laddie Ate

Grosarts

There werna Mair than Four at

Nicht

BOOK II. THROUGH THE

FLOOD

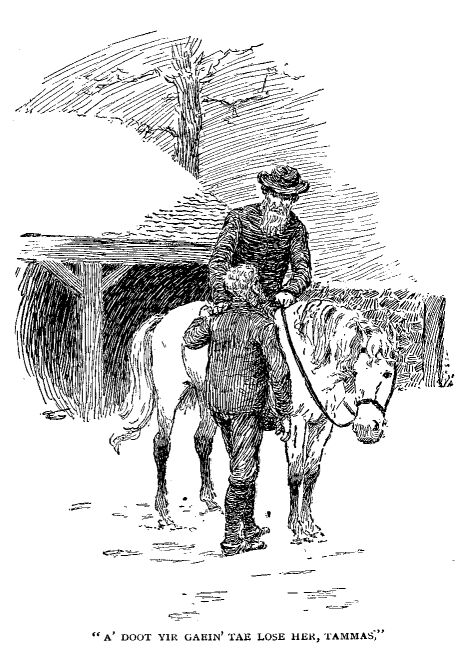

A' doot Yir Gaein' tae Lose Her,

Tammas

The Bonniest, Snoddest, Kindliest

Lass in the Glen

The Winter Night was

Falling Fast

Comin' tae Meet Me in the

Gloamin?

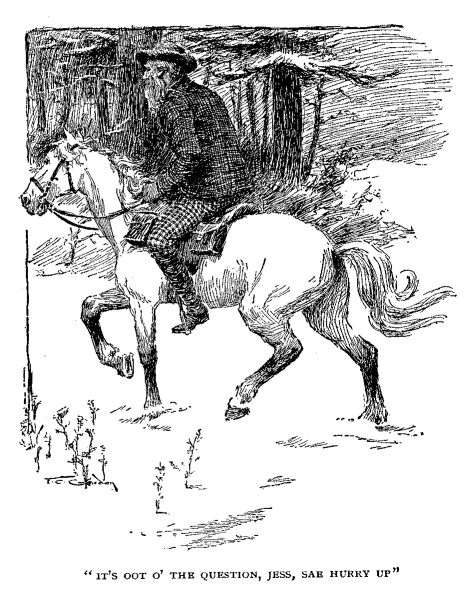

It's oot o' the Question, Jess,

sae Hurry up

It's a Fell Chairge for a

Short Day's Work

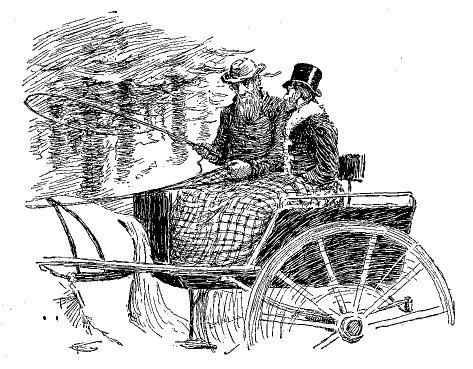

The East had Come to

Meet the West

MacLure Explained that it

would be an Eventful Journey

They Passed

through the Shallow Water without Mishap

A

Heap of Speechless Misery by the Kitchen Fire

Ma ain Dear Man

I'm Proud

to have Met You

BOOK III. A

FIGHT WITH DEATH

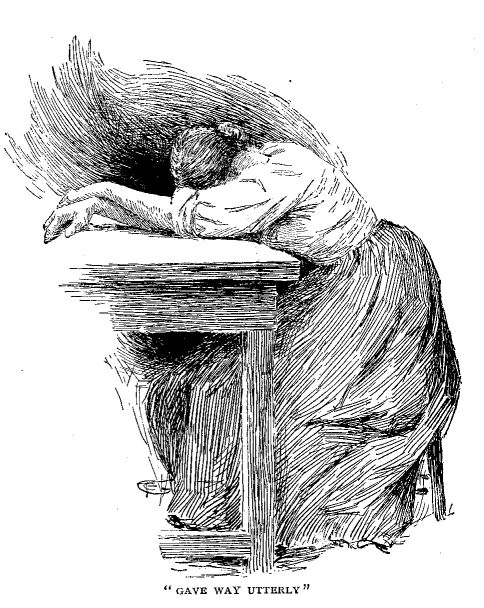

Gave Way Utterly

Fillin' His Lungs for Five and Thirty Year wi' Strong

Drumtochty Air

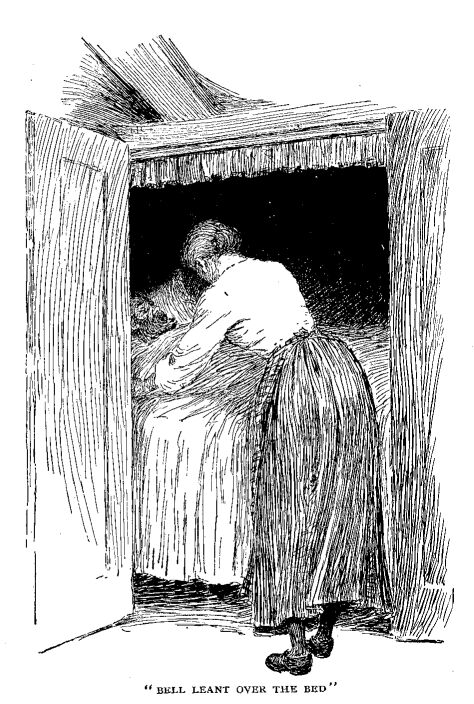

Bell Leant Over the Bed

A Large Tub

The

Lighted Window in Saunder's Cottage

A

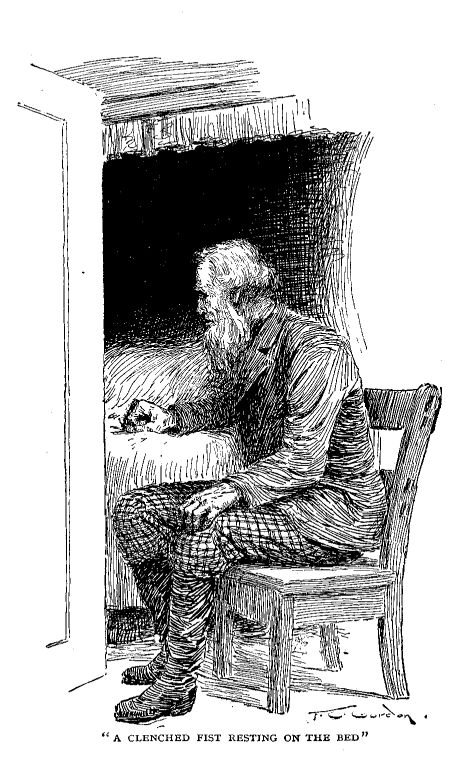

Clenched Fist Resting on the Bed

The

Doctor was Attempting the Highland Fling

Sleepin'

on the Top o' Her Bed

A' Prayed Last

Nicht

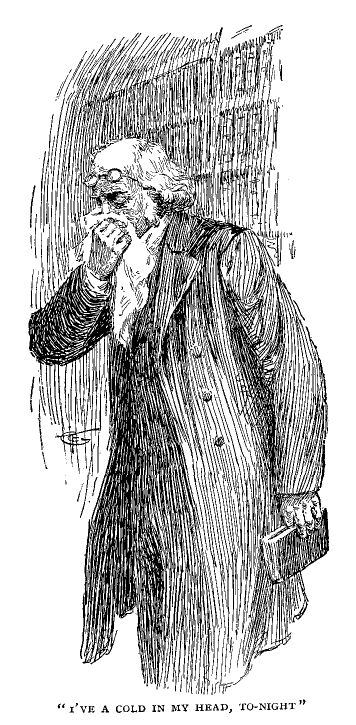

I've a Cold in My Head To-night

Jess Bolted without Delay

BOOK IV. THE DOCTOR'S LAST JOURNEY

Comin' in Frae Glen Urtach

Drumsheugh

was Full of Tact

Told Drumsheugh that the

Doctor was not Able to Rise

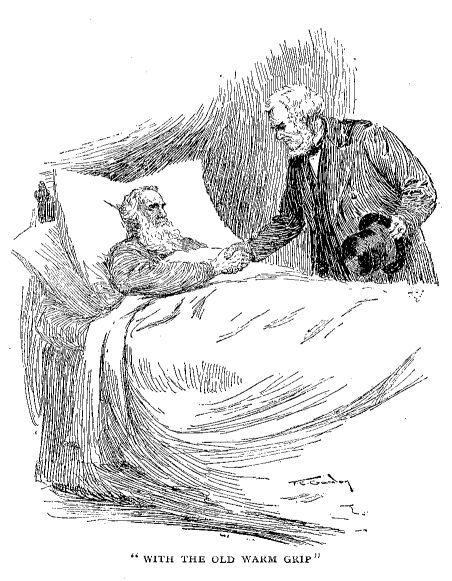

With the Old

Warm Grip

Drumsheugh Looked Wistfully

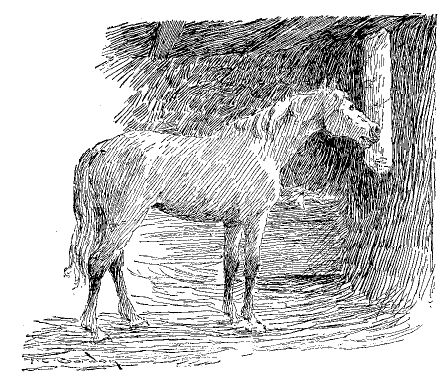

Wud Gie Her a Bite o' Grass

Ma Mither's Bible

It's a

Coorse Nicht, Jess

She's Carryin' a Licht

in Her Hand

BOOK V. THE

MOURNING OF THE GLEN

The Tochty Ran with

Black, Swollen Stream

Toiled Across the

Glen

There was Nae Use Trying tae Dig Oot

the Front Door

Ane of Them Gied Ower the

Head in a Drift

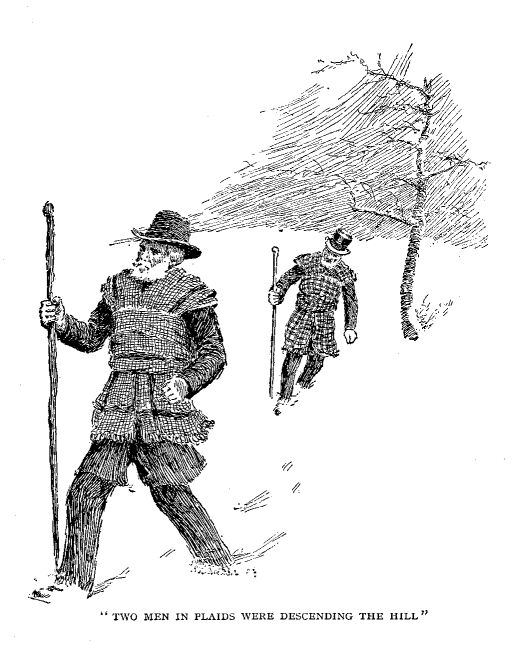

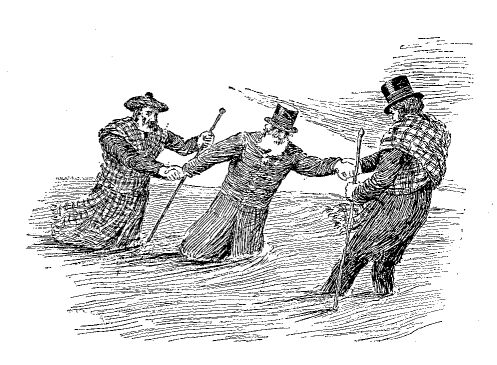

Two Men in Plaids were

Descending the Hill

Jined Hands and Cam

ower Fine

Twa Horses, Ane afore the Ither

He had Left His Overcoat, and was in Black

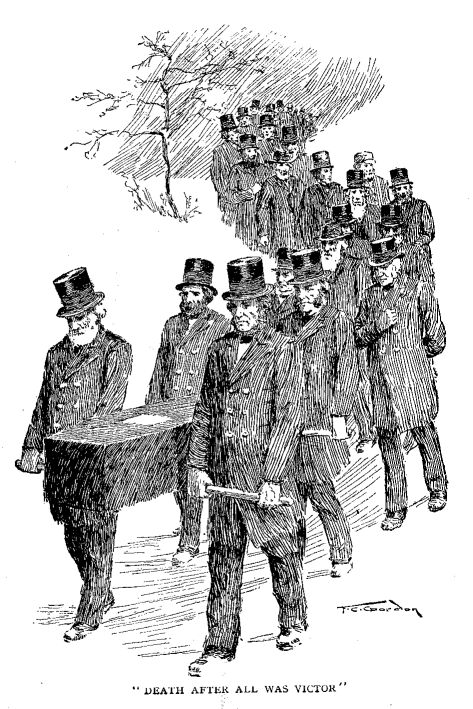

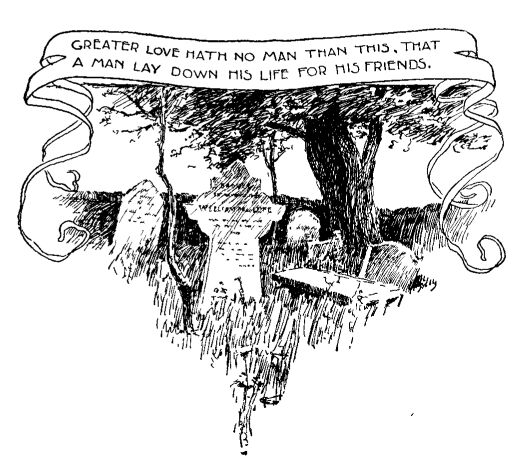

Death after All was Victor

She Began to Neigh

They

had Set to Work

Standing at the Door

Finis

It is with great good will that I write this short preface to the edition of “A Doctor of the Old School” (which has been illustrated by Mr. Gordon after an admirable and understanding fashion) because there are two things that I should like to say to my readers, being also my friends.

One, is to answer a question that has been often and fairly asked. Was there ever any doctor so self-forgetful and so utterly Christian as William MacLure? To which I am proud to reply, on my conscience: Not one man, but many in Scotland and in the South country. I will dare prophecy also across the sea.

It has been one man's good fortune to know four country doctors, not one of whom was without his faults—Weelum was not perfect—but who, each one, might have sat for my hero. Three are now resting from their labors, and the fourth, if he ever should see these lines, would never identify himself.

Then I desire to thank my readers, and chiefly the medical profession for the reception given to the Doctor of Drumtochty.

For many years I have desired to pay some tribute to a class whose service to the community was known to every countryman, but after the tale had gone forth my heart failed. For it might have been despised for the little grace of letters in the style and because of the outward roughness of the man. But neither his biographer nor his circumstances have been able to obscure MacLure who has himself won all honest hearts, and received afresh the recognition of his more distinguished brethren. From all parts of the English-speaking world letters have come in commendation of Weelum MacLure, and many were from doctors who had received new courage. It is surely more honor than a new writer could ever have deserved to receive the approbation of a profession whose charity puts us all to shame.

May I take this first opportunity to declare how deeply my heart has been touched by the favor shown to a simple book by the American people, and to express my hope that one day it may be given me to see you face to face.

IAN MACLAREN. Liverpool, Oct. 4, 1895.

Drumtochty was accustomed to break every law of health, except wholesome food and fresh air, and yet had reduced the Psalmist's farthest limit to an average life-rate. Our men made no difference in their clothes for summer or winter, Drumsheugh and one or two of the larger farmers condescending to a topcoat on Sabbath, as a penalty of their position, and without regard to temperature. They wore their blacks at a funeral, refusing to cover them with anything, out of respect to the deceased, and standing longest in the kirkyard when the north wind was blowing across a hundred miles of snow. If the rain was pouring at the Junction, then Drumtochty stood two minutes longer through sheer native dourness till each man had a cascade from the tail of his coat, and hazarded the suggestion, halfway to Kildrummie, that it had been “a bit scrowie,” a “scrowie” being as far short of a “shoor” as a “shoor” fell below “weet.”

This sustained defiance of the elements provoked occasional judgments in the shape of a “hoast” (cough), and the head of the house was then exhorted by his women folk to “change his feet” if he had happened to walk through a burn on his way home, and was pestered generally with sanitary precautions. It is right to add that the gudeman treated such advice with contempt, regarding it as suitable for the effeminacy of towns, but not seriously intended for Drumtochty. Sandy Stewart “napped” stones on the road in his shirt sleeves, wet or fair, summer and winter, till he was persuaded to retire from active duty at eighty-five, and he spent ten years more in regretting his hastiness and criticising his successor. The ordinary course of life, with fine air and contented minds, was to do a full share of work till seventy, and then to look after “orra” jobs well into the eighties, and to “slip awa” within sight of ninety. Persons above ninety were understood to be acquitting themselves with credit, and assumed airs of authority, brushing aside the opinions of seventy as immature, and confirming their conclusions with illustrations drawn from the end of last century.

When Hillocks' brother so far forgot himself as to “slip awa” at sixty, that worthy man was scandalized, and offered laboured explanations at the “beerial.”

“It's an awfu' business ony wy ye look at it, an' a sair trial tae us a'. A' never heard tell o' sic a thing in oor family afore, an' it's no easy accoontin' for't.

“The gudewife was sayin' he wes never the same sin' a weet nicht he lost himsel on the muir and slept below a bush; but that's neither here nor there. A'm thinkin' he sappit his constitution thae twa years he wes grieve aboot England. That wes thirty years syne, but ye're never the same aifter thae foreign climates.”

Drumtochty listened patiently to Hillocks' apology, but was not satisfied.

“It's clean havers about the muir. Losh keep's, we've a' sleepit oot and never been a hair the waur.

“A' admit that England micht hae dune the job; it's no cannie stravagin' yon wy frae place tae place, but Drums never complained tae me if he hed been nippit in the Sooth.”

The parish had, in fact, lost confidence in Drums after his wayward experiment with a potato-digging machine, which turned out a lamentable failure, and his premature departure confirmed our vague impression of his character.

“He's awa noo,” Drumsheugh summed up, after opinion had time to form; “an' there were waur fouk than Drums, but there's nae doot he was a wee flichty.”

When illness had the audacity to attack a Drumtochty man, it was described as a “whup,” and was treated by the men with a fine negligence. Hillocks was sitting in the post-office one afternoon when I looked in for my letters, and the right side of his face was blazing red. His subject of discourse was the prospects of the turnip “breer,” but he casually explained that he was waiting for medical advice.

“The gudewife is keepin' up a ding-dong frae mornin' till nicht aboot ma face, and a'm fair deaved (deafened), so a'm watchin' for MacLure tae get a bottle as he comes wast; yon's him noo.”

The doctor made his diagnosis from horseback on sight, and stated the result with that admirable clearness which endeared him to Drumtochty.

“Confoond ye, Hillocks, what are ye ploiterin' aboot here for in the weet wi' a face like a boiled beet? Div ye no ken that ye've a titch o' the rose (erysipelas), and ocht tae be in the hoose? Gae hame wi' ye afore a' leave the bit, and send a haflin for some medicine. Ye donnerd idiot, are ye ettlin tae follow Drums afore yir time?” And the medical attendant of Drumtochty continued his invective till Hillocks started, and still pursued his retreating figure with medical directions of a simple and practical character.

“A'm watchin', an' peety ye if ye pit aff time. Keep yir bed the mornin', and dinna show yir face in the fields till a' see ye. A'll gie ye a cry on Monday—sic an auld fule—but there's no are o' them tae mind anither in the hale pairish.”

Hillocks' wife informed the kirkyaird that the doctor “gied the gudeman an awfu' clear-in',” and that Hillocks “wes keepin' the hoose,” which meant that the patient had tea breakfast, and at that time was wandering about the farm buildings in an easy undress with his head in a plaid.

It was impossible for a doctor to earn even the most modest competence from a people of such scandalous health, and so MacLure had annexed neighbouring parishes. His house—little more than a cottage—stood on the roadside among the pines towards the head of our Glen, and from this base of operations he dominated the wild glen that broke the wall of the Grampians above Drumtochty—where the snow drifts were twelve feet deep in winter, and the only way of passage at times was the channel of the river—and the moorland district westwards till he came to the Dunleith sphere of influence, where there were four doctors and a hydropathic. Drumtochty in its length, which was eight miles, and its breadth, which was four, lay in his hand; besides a glen behind, unknown to the world, which in the night time he visited at the risk of life, for the way thereto was across the big moor with its peat holes and treacherous bogs. And he held the land eastwards towards Muirtown so far as Geordie, the Drumtochty post, travelled every day, and could carry word that the doctor was wanted. He did his best for the need of every man, woman and child in this wild, straggling district, year in, year out, in the snow and in the heat, in the dark and in the light, without rest, and without holiday for forty years.

One horse could not do the work of this man, but we liked best to see him on his old white mare, who died the week after her master, and the passing of the two did our hearts good. It was not that he rode beautifully, for he broke every canon of art, flying with his arms, stooping till he seemed to be speaking into Jess's ears, and rising in the saddle beyond all necessity. But he could rise faster, stay longer in the saddle, and had a firmer grip with his knees than any one I ever met, and it was all for mercy's sake. When the reapers in harvest time saw a figure whirling past in a cloud of dust, or the family at the foot of Glen Urtach, gathered round the fire on a winter's night, heard the rattle of a horse's hoofs on the road, or the shepherds, out after the sheep, traced a black speck moving across the snow to the upper glen, they knew it was the doctor, and, without being conscious of it, wished him God speed.

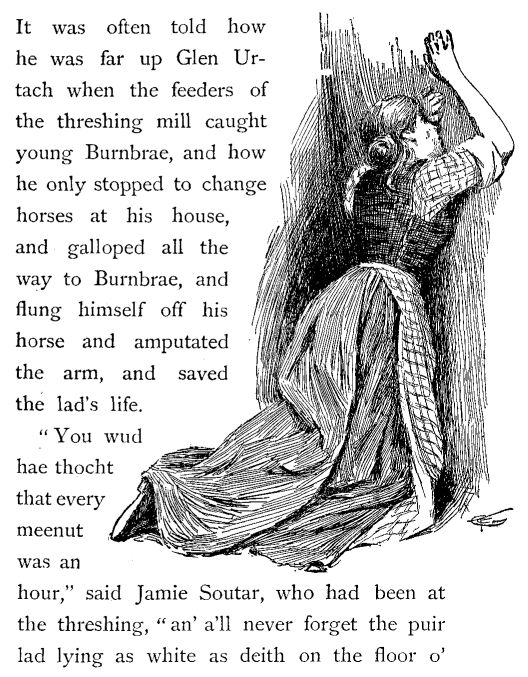

Before and behind his saddle were strapped the instruments and medicines the doctor might want, for he never knew what was before him. There were no specialists in Drumtochty, so this man had to do everything as best he could, and as quickly. He was chest doctor and doctor for every other organ as well; he was accoucheur and surgeon; he was oculist and aurist; he was dentist and chloroformist, besides being chemist and druggist. It was often told how he was far up Glen Urtach when the feeders of the threshing mill caught young Burnbrae, and how he only stopped to change horses at his house, and galloped all the way to Burnbrae, and flung himself off his horse and amputated the arm, and saved the lad's life.

“You wud hae thocht that every meenut was an hour,” said Jamie Soutar, who had been at the threshing, “an' a'll never forget the puir lad lying as white as deith on the floor o' the loft, wi' his head on a sheaf, an' Burnbrae haudin' the bandage ticht an' prayin' a' the while, and the mither greetin' in the corner.

“'Will he never come?' she cries, an' a' heard the soond o' the horse's feet on the road a mile awa in the frosty air.

“'The Lord be praised!' said Burnbrae, and a' slippit doon the ladder as the doctor came skelpin' intae the close, the foam fleein' frae his horse's mooth.

“Whar is he?' wes a' that passed his lips, an' in five meenuts he hed him on the feedin' board, and wes at his wark—sic wark, neeburs—but he did it weel. An' ae thing a' thocht rael thochtfu' o' him: he first sent aff the laddie's mither tae get a bed ready.

“Noo that's feenished, and his constitution 'ill dae the rest,” and he carried the lad doon the ladder in his airms like a bairn, and laid him in his bed, and waits aside him till he wes sleepin', and then says he: 'Burnbrae, yir gey lad never tae say 'Collie, will yelick?' for a' hevna tasted meat for saxteen hoors.'

“It was michty tae see him come intae the yaird that day, neeburs; the verra look o' him wes victory.”

Jamie's cynicism slipped off in the enthusiasm of this reminiscence, and he expressed the feeling of Drumtochty. No one sent for MacLure save in great straits, and the sight of him put courage in sinking hearts. But this was not by the grace of his appearance, or the advantage of a good bedside manner. A tall, gaunt, loosely made man, without an ounce of superfluous flesh on his body, his face burned a dark brick color by constant exposure to the weather, red hair and beard turning grey, honest blue eyes that look you ever in the face, huge hands with wrist bones like the shank of a ham, and a voice that hurled his salutations across two fields, he suggested the moor rather than the drawing-room. But what a clever hand it was in an operation, as delicate as a woman's, and what a kindly voice it was in the humble room where the shepherd's wife was weeping by her man's bedside.

He was “ill pitten the gither” to begin with, but many of his physical defects were the penalties of his work, and endeared him to the Glen. That ugly scar that cut into his right eyebrow and gave him such a sinister expression, was got one night Jess slipped on the ice and laid him insensible eight miles from home. His limp marked the big snowstorm in the fifties, when his horse missed the road in Glen Urtach, and they rolled together in a drift. MacLure escaped with a broken leg and the fracture of three ribs, but he never walked like other men again. He could not swing himself into the saddle without making two attempts and holding Jess's mane. Neither can you “warstle” through the peat bogs and snow drifts for forty winters without a touch of rheumatism. But they were honorable scars, and for such risks of life men get the Victoria Cross in other fields.

MacLure got nothing but the secret affection of the Glen, which knew that none had ever done one-tenth as much for it as this ungainly, twisted, battered figure, and I have seen a Drumtochty face soften at the sight of MacLure limping to his horse.

Mr. Hopps earned the ill-will of the Glen for ever by criticising the doctor's dress, but indeed it would have filled any townsman with amazement. Black he wore once a year, on Sacrament Sunday, and, if possible, at a funeral; topcoat or waterproof never. His jacket and waistcoat were rough homespun of Glen Urtach wool, which threw off the wet like a duck's back, and below he was clad in shepherd's tartan trousers, which disappeared into unpolished riding boots. His shirt was grey flannel, and he was uncertain about a collar, but certain as to a tie which he never had, his beard doing instead, and his hat was soft felt of four colors and seven different shapes. His point of distinction in dress was the trousers, and they were the subject of unending speculation.

“Some threep that he's worn thae eedentical pair the last twenty year, an' a' mind masel him gettin' a tear ahint, when he was crossin' oor palin', and the mend's still veesible.

“Ithers declare 'at he's got a wab o' claith, and hes a new pair made in Muirtown aince in the twa year maybe, and keeps them in the garden till the new look wears aff.

“For ma ain pairt,” Soutar used to declare, “a' canna mak up my mind, but there's ae thing sure, the Glen wud not like tae see him withoot them: it wud be a shock tae confidence. There's no muckle o' the check left, but ye can aye tell it, and when ye see thae breeks comin' in ye ken that if human pooer can save yir bairn's life it 'ill be dune.”

The confidence of the Glen—and tributary states—was unbounded, and rested partly on long experience of the doctor's resources, and partly on his hereditary connection.

“His father was here afore him,” Mrs. Macfadyen used to explain; “atween them they've hed the countyside for weel on tae a century; if MacLure disna understand oor constitution, wha dis, a' wud like tae ask?”

For Drumtochty had its own constitution and a special throat disease, as became a parish which was quite self-contained between the woods and the hills, and not dependent on the lowlands either for its diseases or its doctors.

“He's a skilly man, Doctor MacLure,” continued my friend Mrs. Macfayden, whose judgment on sermons or anything else was seldom at fault; “an' a kind-hearted, though o' coorse he hes his faults like us a', an' he disna tribble the Kirk often.

“He aye can tell what's wrang wi' a body, an' maistly he can put ye richt, and there's nae new-fangled wys wi' him: a blister for the ootside an' Epsom salts for the inside dis his wark, an' they say there's no an herb on the hills he disna ken.

“If we're tae dee, we're tae dee; an' if we're tae live, we're tae live,” concluded Elspeth, with sound Calvinistic logic; “but a'll say this for the doctor, that whether yir tae live or dee, he can aye keep up a sharp meisture on the skin.”

“But he's no veera ceevil gin ye bring him when there's naethin' wrang,” and Mrs. Macfayden's face reflected another of Mr. Hopps' misadventures of which Hillocks held the copyright.

“Hopps' laddie ate grosarts (gooseberries) till they hed to sit up a' nicht wi' him, an' naethin' wud do but they maun hae the doctor, an' he writes 'immediately' on a slip o' paper.

“Weel, MacLure had been awa a' nicht wi' a shepherd's wife Dunleith wy, and he comes here withoot drawin' bridle, mud up tae the cen.

“'What's a dae here, Hillocks?” he cries; 'it's no an accident, is't?' and when he got aff his horse he cud hardly stand wi' stiffness and tire.

“'It's nane o' us, doctor; it's Hopps' laddie; he's been eatin' ower mony berries.'

“If he didna turn on me like a tiger.

“Div ye mean tae say——'

“'Weesht, weesht,' an' I tried tae quiet him, for Hopps wes comin' oot.

“'Well, doctor,' begins he, as brisk as a magpie, 'you're here at last; there's no hurry with you Scotchmen. My boy has been sick all night, and I've never had one wink of sleep. You might have come a little quicker, that's all I've got to say.'

“We've mair tae dae in Drumtochty than attend tae every bairn that hes a sair stomach,' and a' saw MacLure wes roosed.

“'I'm astonished to hear you speak. Our doctor at home always says to Mrs. 'Opps “Look on me as a family friend, Mrs. 'Opps, and send for me though it be only a headache.”'

“'He'd be mair sparin' o' his offers if he hed four and twenty mile tae look aifter. There's naethin' wrang wi' yir laddie but greed. Gie him a gude dose o' castor oil and stop his meat for a day, an' he 'ill be a' richt the morn.'

“'He 'ill not take castor oil, doctor. We have given up those barbarous medicines.'

“'Whatna kind o' medicines hae ye noo in the Sooth?'

“'Well, you see, Dr. MacLure, we're homoeopathists, and I've my little chest here,' and oot Hopps comes wi' his boxy.

“'Let's see't,' an' MacLure sits doon and taks oot the bit bottles, and he reads the names wi' a lauch every time.

“'Belladonna; did ye ever hear the like? Aconite; it cowes a'. Nux Vomica. What next? Weel, ma mannie,' he says tae Hopps, 'it's a fine ploy, and ye 'ill better gang on wi' the Nux till it's dune, and gie him ony ither o' the sweeties he fancies.

“'Noo, Hillocks, a' maun be aff tae see Drumsheugh's grieve, for he's doon wi' the fever, and it's tae be a teuch fecht. A' hinna time tae wait for dinner; gie me some cheese an' cake in ma haund, and Jess 'ill tak a pail o' meal an' water.

“'Fee; a'm no wantin' yir fees, man; wi' that boxy ye dinna need a doctor; na, na, gie yir siller tae some puir body, Maister Hopps,' an' he was doon the road as hard as he cud lick.”

His fees were pretty much what the folk chose to give him, and he collected them once a year at Kildrummie fair.

“Well, doctor, what am a' awin' ye for the wife and bairn? Ye 'ill need three notes for that nicht ye stayed in the hoose an' a' the veesits.”

“Havers,” MacLure would answer, “prices are low, a'm hearing; gie's thirty shillings.”

“No, a'll no, or the wife 'ill tak ma ears off,” and it was settled for two pounds. Lord Kilspindie gave him a free house and fields, and one way or other, Drumsheugh told me, the doctor might get in about £150 a year, out of which he had to pay his old housekeeper's wages and a boy's, and keep two horses, besides the cost of instruments and books, which he bought through a friend in Edinburgh with much judgment.

There was only one man who ever complained of the doctor's charges, and that was the new farmer of Milton, who was so good that he was above both churches, and held a meeting in his barn. (It was Milton the Glen supposed at first to be a Mormon, but I can't go into that now.) He offered MacLure a pound less than he asked, and two tracts, whereupon MacLure expressed his opinion of Milton, both from a theological and social standpoint, with such vigor and frankness that an attentive audience of Drumtochty men could hardly contain themselves. Jamie Soutar was selling his pig at the time, and missed the meeting, but he hastened to condole with Milton, who was complaining everywhere of the doctor's language.

“Ye did richt tae resist him; it 'ill maybe roose the Glen tae mak a stand; he fair hands them in bondage.

“Thirty shillings for twal veesits, and him no mair than seeven mile awa, an' a'm telt there werena mair than four at nicht.

“Ye 'ill hae the sympathy o' the Glen, for a' body kens yir as free wi' yir siller as yir tracts.

“Wes't 'Beware o' gude warks' ye offered him? Man, ye choose it weel, for he's been colleckin' sae mony thae forty years, a'm feared for him.

“A've often thocht oor doctor's little better than the Gude Samaritan, an' the Pharisees didna think muckle o' his chance aither in this warld or that which is tae come.”

Doctor MacLure did not lead a solemn procession from the sick bed to the dining-room, and give his opinion from the hearthrug with an air of wisdom bordering on the supernatural, because neither the Drumtochty houses nor his manners were on that large scale. He was accustomed to deliver himself in the yard, and to conclude his directions with one foot in the stirrup; but when he left the room where the life of Annie Mitchell was ebbing slowly away, our doctor said not one word, and at the sight of his face her husband's heart was troubled.

He was a dull man, Tammas, who could not read the meaning of a sign, and labored under a perpetual disability of speech; but love was eyes to him that day, and a mouth.

“Is't as bad as yir lookin', doctor? tell's the truth; wull Annie no come through?” and Tammas looked MacLure straight in the face, who never flinched his duty or said smooth things.

“A' wud gie onything tae say Annie hes a chance, but a' daurna; a' doot yir gaein' tae lose her, Tammas.”

MacLure was in the saddle, and as he gave his judgment, he laid his hand on Tammas's shoulder with one of the rare caresses that pass between men.

“It's a sair business, but ye 'ill play the man and no vex Annie; she 'ill dae her best, a'll warrant.”

“An' a'll dae mine,” and Tammas gave MacLure's hand a grip that would have crushed the bones of a weakling. Drumtochty felt in such moments the brotherliness of this rough-looking man, and loved him.

Tammas hid his face in Jess's mane, who looked round with sorrow in her beautiful eyes, for she had seen many tragedies, and in this silent sympathy the stricken man drank his cup, drop by drop.

“A' wesna prepared for this, for a' aye thocht she wud live the langest.... She's younger than me by ten years, and never wes ill.... We've been mairit twal year laist Martinmas, but it's juist like a year the day... A' wes never worthy o' her, the bonniest, snoddest (neatest), kindliest lass in the Glen.... A' never cud mak oot hoo she ever lookit at me, 'at hesna hed ae word tae say aboot her till it's ower late.... She didna cuist up tae me that a' wesna worthy o' her, no her, but aye she said, 'Yir ma ain gudeman, and nane cud be kinder tae me.' ... An' a' wes minded tae be kind, but a' see noo mony little trokes a' micht hae dune for her, and noo the time is bye.... Naebody kens hoo patient she wes wi' me, and aye made the best o 'me, an' never pit me tae shame afore the fouk.... An' we never hed ae cross word, no ane in twal year.... We were mair nor man and wife, we were sweethearts a' the time.... Oh, ma bonnie lass, what 'ill the bairnies an' me dae withoot ye, Annie?”

The winter night was falling fast, the snow lay deep upon the ground, and the merciless north wind moaned through the close as Tammas wrestled with his sorrow dry-eyed, for tears were denied Drumtochty men. Neither the doctor nor Jess moved hand or foot, but their hearts were with their fellow creature, and at length the doctor made a sign to Marget Howe, who had come out in search of Tammas, and now stood by his side.

“Dinna mourn tae the brakin' o' yir hert, Tammas,” she said, “as if Annie an' you hed never luved. Neither death nor time can pairt them that luve; there's naethin' in a' the warld sae strong as luve. If Annie gaes frae the sichot' yir een she 'ill come the nearer tae yir hert. She wants tae see ye, and tae hear ye say that ye 'ill never forget her nicht nor day till ye meet in the land where there's nae pairtin'. Oh, a' ken what a'm saying', for it's five year noo sin George gied awa, an' he's mair wi' me noo than when he wes in Edinboro' and I was in Drumtochty.”

“Thank ye kindly, Marget; thae are gude words and true, an' ye hev the richt tae say them; but a' canna dae without seem' Annie comin' tae meet me in the gloamin', an' gaein' in an' oot the hoose, an' hearin' her ca' me by ma name, an' a'll no can tell her that a'luve her when there's nae Annie in the hoose.

“Can naethin' be dune, doctor? Ye savit Flora Cammil, and young Burnbrae, an' yon shepherd's wife Dunleith wy, an' we were a sae prood o' ye, an' pleased tae think that ye hed keepit deith frae anither hame. Can ye no think o' somethin' tae help Annie, and gie her back tae her man and bairnies?” and Tammas searched the doctor's face in the cold, weird light.

“There's nae pooer on heaven or airth like luve,” Marget said to me afterwards; “it maks the weak strong and the dumb tae speak. Oor herts were as water afore Tammas's words, an' a' saw the doctor shake in his saddle. A' never kent till that meenut hoo he hed a share in a'body's grief, an' carried the heaviest wecht o' a' the Glen. A' peetied him wi' Tammas lookin' at him sae wistfully, as if he hed the keys o' life an' deith in his hands. But he wes honest, and wudna hold oot a false houp tae deceive a sore hert or win escape for himsel'.”

“Ye needna plead wi' me, Tammas, to dae the best a' can for yir wife. Man, a' kent her lang afore ye ever luved her; a' brocht her intae the warld, and a' saw her through the fever when she wes a bit lassikie; a' closed her mither's een, and it was me hed tae tell her she wes an orphan, an' nae man wes better pleased when she got a gude husband, and a' helpit her wi' her fower bairns. A've naither wife nor bairns o' ma own, an' a' coont a' the fouk o' the Glen ma family. Div ye think a' wudna save Annie if I cud? If there wes a man in Muirtown 'at cud dae mair for her, a'd have him this verra nicht, but a' the doctors in Perthshire are helpless for this tribble.

“Tammas, ma puir fallow, if it could avail, a' tell ye a' wud lay doon this auld worn-oot ruckle o' a body o' mine juist tae see ye baith sittin' at the fireside, an' the bairns roond ye, couthy an' canty again; but it's no tae be, Tammas, it's no tae be.”

“When a' lookit at the doctor's face,” Marget said, “a' thocht him the winsomest man a' ever saw. He was transfigured that nicht, for a'm judging there's nae transfiguration like luve.”

“It's God's wull an' maun be borne, but it's a sair wull for me, an' a'm no ungratefu' tae you, doctor, for a' ye've dune and what ye said the nicht,” and Tammas went back to sit with Annie for the last time.

Jess picked her way through the deep snow to the main road, with a skill that came of long experience, and the doctor held converse with her according to his wont.

“Eh, Jess wumman, yon wes the hardest wark a' hae tae face, and a' wud raither hae ta'en ma chance o' anither row in a Glen Urtach drift than tell Tammas Mitchell his wife wes deein'.

“A' said she cudna be cured, and it wes true, for there's juist ae man in the land fit for't, and they micht as weel try tae get the mune oot o' heaven. Sae a' said naethin' tae vex Tammas's hert, for it's heavy eneuch withoot regrets.

“But it's hard, Jess, that money wull buy life after a', an' if Annie wes a duchess her man wudna lose her; but bein' only a puir cottar's wife, she maun dee afore the week's oot.

“Gin we hed him the morn there's little doot she would be saved, for he hesna lost mair than five per cent, o' his cases, and they 'ill be puir toon's craturs, no strappin women like Annie.

“It's oot o' the question, Jess, sae hurry up, lass, for we've hed a heavy day. But it wud be the grandest thing that was ever dune in the Glen in oor time if it could be managed by hook or crook.

“We 'ill gang and see Drumsheugh, Jess; he's anither man sin' Geordie Hoo's deith, and he wes aye kinder than fouk kent;” and the doctor passed at a gallop through the village, whose lights shone across the white frost-bound road.

“Come in by, doctor; a' heard ye on the road; ye 'ill hae been at Tammas Mitchell's; hoo's the gudewife? a' doot she's sober.”

“Annie's deein', Drumsheugh, an' Tammas is like tae brak his hert.”

“That's no lichtsome, doctor, no lichtsome ava, for a' dinna ken ony man in Drumtochty sae bund up in his wife as Tammas, and there's no a bonnier wumman o' her age crosses our kirk door than Annie, nor a cleverer at her wark. Man, ye 'ill need tae pit yir brains in steep. Is she clean beyond ye?”

“Beyond me and every ither in the land but ane, and it wud cost a hundred guineas tae bring him tae Drumtochty.”

“Certes, he's no blate; it's a fell chairge for a short day's work; but hundred or no hundred we'll hae him, an' no let Annie gang, and her no half her years.”

“Are ye meanin' it, Drumsheugh?” and MacLure turned white below the tan. “William MacLure,” said Drumsheugh, in one of the few confidences that ever broke the Drumtochty reserve, “a'm a lonely man, wi' naebody o' ma ain blude tae care for me livin', or tae lift me intae ma coffin when a'm deid.

“A' fecht awa at Muirtown market for an extra pound on a beast, or a shillin' on the quarter o' barley, an' what's the gude o't? Burnbrae gaes aff tae get a goon for his wife or a buke for his college laddie, an' Lachlan Campbell 'ill no leave the place noo without a ribbon for Flora.

“Ilka man in the Klldrummie train has some bit fairin' his pooch for the fouk at hame that he's bocht wi' the siller he won.

“But there's naebody tae be lookin' oot for me, an' comin' doon the road tae meet me, and daffin' (joking) wi' me about their fairing, or feeling ma pockets. Ou ay, a've seen it a' at ither hooses, though they tried tae hide it frae me for fear a' wud lauch at them. Me lauch, wi' ma cauld, empty hame!

“Yir the only man kens, Weelum, that I aince luved the noblest wumman in the glen or onywhere, an' a' luve her still, but wi' anither luve noo.

“She had given her heart tae anither, or a've thocht a' micht hae won her, though nae man be worthy o' sic a gift. Ma hert turned tae bitterness, but that passed awa beside the brier bush whar George Hoo lay yon sad simmer time. Some day a'll tell ye ma story, Weelum, for you an' me are auld freends, and will be till we dee.”

MacLure felt beneath the table for Drumsheugh's hand, but neither man looked at the other.

“Weel, a' we can dae noo, Weelum, gin we haena mickle brichtness in oor ain names, is tae keep the licht frae gaein' oot in anither hoose. Write the telegram, man, and Sandy 'ill send it aff frae Kildrummie this verra nicht, and ye 'ill hae yir man the morn.”

“Yir the man a' coonted ye, Drumsheugh, but ye 'ill grant me ae favor. Ye 'ill lat me pay the half, bit by bit—a' ken yir wullin' tae dae't a'—but a' haena mony pleasures, an' a' wud like tae hae ma ain share in savin' Annie's life.”

Next morning a figure received Sir George on the Kildrummie platform, whom that famous surgeon took for a gillie, but who introduced himself as “MacLure of Drumtochty.” It seemed as if the East had come to meet the West when these two stood together, the one in travelling furs, handsome and distinguished, with his strong, cultured face and carriage of authority, a characteristic type of his profession; and the other more marvellously dressed than ever, for Drumsheugh's topcoat had been forced upon him for the occasion, his face and neck one redness with the bitter cold; rough and ungainly, yet not without some signs of power in his eye and voice, the most heroic type of his noble profession. MacLure compassed the precious arrival with observances till he was securely seated in Drumsheugh's dog cart—a vehicle that lent itself to history—with two full-sized plaids added to his equipment—Drumsheugh and Hillocks had both been requisitioned—and MacLure wrapped another plaid round a leather case, which was placed below the seat with such reverence as might be given to the Queen's regalia. Peter attended their departure full of interest, and as soon as they were in the fir woods MacLure explained that it would be an eventful journey.

“It's a richt in here, for the wind disna get at the snaw, but the drifts are deep in the Glen, and th'ill be some engineerin' afore we get tae oor destination.”

Four times they left the road and took their way over fields, twice they forced a passage through a slap in a dyke, thrice they used gaps in the paling which MacLure had made on his downward journey.

“A' seleckit the road this mornin', an' a' ken the depth tae an inch; we 'ill get through this steadin' here tae the main road, but oor worst job 'ill be crossin' the Tochty.

“Ye see the bridge hes been shaken wi' this winter's flood, and we daurna venture on it, sae we hev tae ford, and the snaw's been melting up Urtach way. There's nae doot the water's gey big, and it's threatenin' tae rise, but we 'ill win through wi' a warstle.

“It micht be safer tae lift the instruments oot o' reach o' the water; wud ye mind haddin' them on yir knee till we're ower, an' keep firm in yir seat in case we come on a stane in the bed o' the river.”

By this time they had come to the edge, and it was not a cheering sight. The Tochty had spread out over the meadows, and while they waited they could see it cover another two inches on the trunk of a tree. There are summer floods, when the water is brown and flecked with foam, but this was a winter flood, which is black and sullen, and runs in the centre with a strong, fierce, silent current. Upon the opposite side Hillocks stood to give directions by word and hand, as the ford was on his land, and none knew the Tochty better in all its ways.

They passed through the shallow water without mishap, save when the wheel struck a hidden stone or fell suddenly into a rut; but when they neared the body of the river MacLure halted, to give Jess a minute's breathing.

“It 'ill tak ye a' yir time, lass, an' a' wud raither be on yir back; but ye never failed me yet, and a wumman's life is hangin' on the crossin'.”

With the first plunge into the bed of the stream the water rose to the axles, and then it crept up to the shafts, so that the surgeon could feel it lapping in about his feet, while the dogcart began to quiver, and it seemed as if it were to be carried away. Sir George was as brave as most men, but he had never forded a Highland river in flood, and the mass of black water racing past beneath, before, behind him, affected his imagination and shook his nerves. He rose from his seat and ordered MacLure to turn back, declaring that he would be condemned utterly and eternally if he allowed himself to be drowned for any person.

“Sit doon,” thundered MacLure; “condemned ye will be suner or later gin ye shirk yir duty, but through the water ye gang the day.”

Both men spoke much more strongly and shortly, but this is what they intended to say, and it was MacLure that prevailed.

Jess trailed her feet along the ground with cunning art, and held her shoulder against the stream; MacLure leant forward in his seat, a rein in each hand, and his eyes fixed on Hillocks, who was now standing up to the waist in the water, shouting directions and cheering on horse and driver.

“Haud tae the richt, doctor; there's a hole yonder. Keep oot o't for ony sake.

That's heap of speechless misery by the kitchen fire, and carried him off to the barn, and spread some corn on the threshing floor and thrust a flail into his hands.

“Noo we've tae begin, an' we 'ill no be dune for an' oor, and ye've tae lay on withoot stoppin' till a' come for ye, an' a'll shut the door tae haud in the noise, an' keep yir dog beside ye, for there maunna be a cheep aboot the hoose for Annie's sake.”

“A'll dae onything ye want me, but if—if—”

“A'll come for ye, Tammas, gin there be danger; but what are ye feared for wi' the Queen's ain surgeon here?”

Fifty minutes did the flail rise and fall, save twice, when Tammas crept to the door and listened, the dog lifting his head and whining.

It seemed twelve hours instead of one when the door swung back, and MacLure filled the doorway, preceded by a great burst of light, for the sun had arisen on the snow.

His face was as tidings of great joy, and Elspeth told me that there was nothing like it to be seen that afternoon for glory, save the sun itself in the heavens.

“A' never saw the marrow o't, Tammas, an' a'll never see the like again; it's a' ower, man, withoot a hitch frae beginnin' tae end, and she's fa'in' asleep as fine as ye like.”

“Dis he think Annie ... 'ill live?”

“Of coorse he dis, and be aboot the hoose inside a month; that's the gud o' bein' a clean-bluided, weel-livin'——”

“Preserve ye, man, what's wrang wi' ye? it's a mercy a' keppit ye, or we wud hev hed anither job for Sir George.

“Ye're a richt noo; sit doon on the strae. A'll come back in a whilie, an' ye i'll see Annie juist for a meenut, but ye maunna say a word.” Marget took him in and let him kneel by Annie's bedside.

He said nothing then or afterwards, for speech came only once in his lifetime to Tammas, but Annie whispered, “Ma ain dear man.”

When the doctor placed the precious bag beside Sir George in our solitary first next morning, he laid a cheque beside it and was about to leave.

“No, no,” said the great man. “Mrs. Macfayden and I were on the gossip last night, and I know the whole story about you and your friend.

“You have some right to call me a coward, but I'll never let you count me a mean, miserly rascal,” and the cheque with Drumsheugh's painful writing fell in fifty pieces on the floor.

As the train began to move, a voice from the first called so that all the station heard. “Give's another shake of your hand, MacLure; I'm proud to have met you; you are an honor to our profession. Mind the antiseptic dressings.”

It was market day, but only Jamie Soutar and Hillocks had ventured down.

“Did ye hear yon, Hillocks? hoo dae ye feel? A'll no deny a'm lifted.”

Halfway to the Junction Hillocks had recovered, and began to grasp the situation.

“Tell's what he said. A' wud like to hae it exact for Drumsheugh.”

“Thae's the eedentical words, an' they're true; there's no a man in Drumtochty disna ken that, except ane.”

“An' wha's thar, Jamie?”

“It's Weelum MacLure himsel. Man, a've often girned that he sud fecht awa for us a', and maybe dee before he kent that he hed githered mair luve than ony man in the Glen.

“'A'm prood tae hae met ye', says Sir George, an' him the greatest doctor in the land. 'Yir an honor tae oor profession.'

“Hillocks, a' wudna hae missed it for twenty notes,” said James Soutar, cynic-in-ordinary to the parish of Drumtochty.

When Drumsheugh's grieve was brought to the gates of death by fever, caught, as was supposed, on an adventurous visit to Glasgow, the London doctor at Lord Kilspindie's shooting lodge looked in on his way from the moor, and declared it impossible for Saunders to live through the night.

“I give him six hours, more or less; it is only a question of time,” said the oracle, buttoning his gloves and getting into the brake; “tell your parish doctor that I was sorry not to have met him.”

Bell heard this verdict from behind the door, and gave way utterly, but Drumsheugh declined to accept it as final, and devoted himself to consolation.

“Dinna greet like that, Bell wumman, sae lang as Saunders is still living'; a'll never give up houp, for ma pairt, till oor ain man says the word.

“A' the doctors in the land dinna ken as muckle aboot us as Weelum MacLure, an' he's ill tae beat when he's trying tae save a man's life.”

MacLure, on his coming, would say nothing, either weal or woe, till he had examined Saunders. Suddenly his face turned into iron before their eyes, and he looked like one encountering a merciless foe. For there was a feud between MacLure and a certain mighty power which had lasted for forty years in Drumtochty.

“The London doctor said that Saunders wud sough awa afore mornin', did he? Weel, he's an authority on fevers an' sic like diseases, an' ought tae ken.

“It's may be presumptous o' me tae differ frae him, and it wudna be verra respectfu' o' Saunders tae live aifter this opeenion. But Saunders wes awe thraun an' ill tae drive, an' he's as like as no tae gang his own gait.

“A'm no meanin' tae reflect on sae clever a man, but he didna ken the seetuation. He can read fevers like a buik, but he never cam across sic a thing as the Drumtochty constitution a' his days.

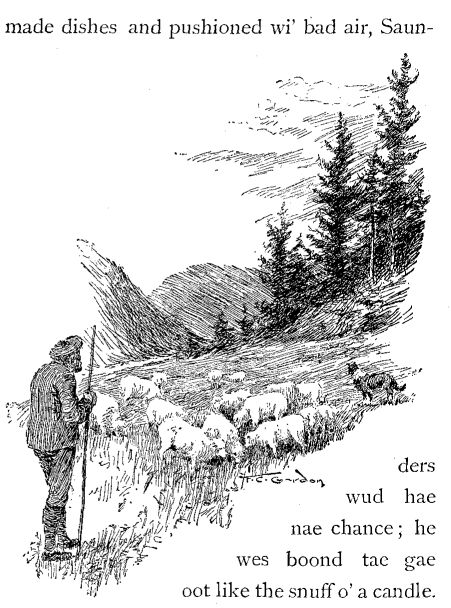

“Ye see, when onybody gets as low as puir Saunders here, it's juist a hand to hand wrastle atween the fever and his constitution, an' of coorse, if he had been a shilpit, stuntit, feckless effeegy o' a cratur, fed on tea an' made dishes and pushioned wi' bad air, Saunders wud hae nae chance; he wes boond tae gae oot like the snuff o' a candle.

“But Saunders hes been fillin' his lungs for five and thirty year wi' strong Drumtochty air, an' eatin' naethin' but kirny aitmeal, and drinkin' naethin' but fresh milk frae the coo, an' followin' the ploo through the new-turned sweet-smellin' earth, an' swingin' the scythe in haytime and harvest, till the legs an' airms o' him were iron, an' his chest wes like the cuttin' o' an oak tree.

“He's a waesome sicht the nicht, but Saunders wes a buirdly man aince, and wull never lat his life be taken lichtly frae him. Na, na, he hesna sinned against Nature, and Nature 'ill stand by him noo in his oor o' distress.

“A' daurna say yea, Bell, muckle as a' wud like, for this is an evil disease, cunnin, an' treacherous as the deevil himsel', but a' winna say nay, sae keep yir hert frae despair.

“It wull be a sair fecht, but it 'ill be settled one wy or anither by sax o'clock the morn's morn. Nae man can prophecee hoo it 'ill end, but ae thing is certain, a'll no see deith tak a Drumtochty man afore his time if a' can help it.

“Noo, Bell ma wumman, yir near deid wi' tire, an' nae wonder. Ye've dune a' ye cud for yir man, an' ye'll lippen (trust) him the nicht tae Drumsheugh an' me; we 'ill no fail him or you.

“Lie doon an' rest, an' if it be the wull o' the Almichty a'll wauken ye in the mornin' tae see a livin' conscious man, an' if it be ither-wise a'll come for ye the suner, Bell,” and the big red hand went out to the anxious wife. “A' gie ye ma word.”

Bell leant over the bed, and at the sight of Saunders' face a superstitious dread seized her.

“See, doctor, the shadow of deith is on him that never lifts. A've seen it afore, on ma father an' mither. A' canna leave him, a' canna leave him.”

“It's hoverin', Bell, but it hesna fallen; please God it never wull. Gang but and get some sleep, for it's time we were at oor work.

“The doctors in the toons hae nurses an' a' kinds o' handy apparatus,” said MacLure to Drumsheugh when Bell had gone, “but you an' me 'ill need tae be nurse the nicht, an' use sic things as we hev.

“It 'ill be a lang nicht and anxious wark, but a' wud raither hae ye, auld freend, wi' me than ony man in the Glen. Ye're no feared tae gie a hand?”

“Me feared? No, likely. Man, Saunders cam tae me a haflin, and hes been on Drumsheugh for twenty years, an' though he be a dour chiel, he's a faithfu' servant as ever lived. It's waesome tae see him lyin' there moanin' like some dumb animal frae mornin' tae nicht, an' no able tae answer his ain wife when she speaks.

“Div ye think, Weelum, he hes a chance?”

“That he hes, at ony rate, and it 'ill no be your blame or mine if he hesna mair.”

While he was speaking, MacLure took off his coat and waistcoat and hung them on the back of the door. Then he rolled up the sleeves of his shirt and laid bare two arms that were nothing but bone and muscle.

“It gar'd ma very blood rin faster tae the end of ma fingers juist tae look at him,” Drumsheugh expatiated afterwards to Hillocks, “for a' saw noo that there was tae be a stand-up fecht atween him an' deith for Saunders, and when a' thocht o' Bell an' her bairns, a' kent wha wud win.

“'Aff wi' yir coat, Drumsheugh,' said MacLure; 'ye 'ill need tae bend yir back the nicht; gither a' the pails in the hoose and fill them at the spring, an' a'll come doon tae help ye wi' the carryin'.'”

It was a wonderful ascent up the steep pathway from the spring to the cottage on its little knoll, the two men in single file, bareheaded, silent, solemn, each with a pail of water in either hand, MacLure limping painfully in front, Drumsheugh blowing behind; and when they laid down their burden in the sick room, where the bits of furniture had been put to a side and a large tub held the centre, Drumsheugh looked curiously at the doctor.

“No, a'm no daft; ye needna be feared; but yir tae get yir first lesson in medicine the nicht, an' if we win the battle ye can set up for yersel in the Glen.

“There's twa dangers—that Saunders' strength fails, an' that the force o' the fever grows; and we have juist twa weapons.

“Yon milk on the drawers' head an' the bottle of whisky is tae keep up the strength, and this cool caller water is tae keep doon the fever.

“We 'ill cast oot the fever by the virtue o' the earth an' the water.”

“Div ye mean tae pit Saunders in the tub?”

“Ye hiv it noo, Drumsheugh, and that's hoo a' need yir help.”

“Man, Hillocks,” Drumsheugh used to moralize, as often as he remembered that critical night, “it wes humblin' tae see hoo low sickness can bring a pooerfu' man, an' ocht tae keep us frae pride.”

“A month syne there wesna a stronger man in the Glen than Saunders, an' noo he wes juist a bundle o' skin and bone, that naither saw nor heard, nor moved nor felt, that kent naethin' that was dune tae him.

“Hillocks, a' wudna hae wished ony man tae hev seen Saunders—for it wull never pass frae before ma een as long as a' live—but a' wish a' the Glen hed stude by MacLure kneelin' on the floor wi' his sleeves up tae his oxters and waitin' on Saunders.

“Yon big man wes as pitifu' an' gentle as a wumman, and when he laid the puir fallow in his bed again, he happit him ower as a mither dis her bairn.”

Thrice it was done, Drumsheugh ever bringing up colder water from the spring, and twice MacLure was silent; but after the third time there was a gleam in his eye.

“We're haudin' oor ain; we're no bein' maistered, at ony rate; mair a' canna say for three oors.

“We 'ill no need the water again, Drumsheugh; gae oot and tak a breath o' air; a'm on gaird masel.”

It was the hour before daybreak, and Drumsheugh wandered through fields he had trodden since childhood. The cattle lay sleeping in the pastures; their shadowy forms, with a patch of whiteness here and there, having a weird suggestion of death. He heard the burn running over the stones; fifty years ago he had made a dam that lasted till winter. The hooting of an owl made him start; one had frightened him as a boy so that he ran home to his mother—she died thirty years ago. The smell of ripe corn filled the air; it would soon be cut and garnered. He could see the dim outlines of his house, all dark and cold; no one he loved was beneath the roof. The lighted window in Saunders' cottage told where a man hung between life and death, but love was in that home. The futility of life arose before this lonely man, and overcame his heart with an indescribable sadness. What a vanity was all human labour, what a mystery all human life.

But while he stood, subtle change came over the night, and the air trembled round him as if one had whispered. Drumsheugh lifted his head and looked eastwards. A faint grey stole over the distant horizon, and suddenly a cloud reddened before his eyes. The sun was not in sight, but was rising, and sending forerunners before his face. The cattle began to stir, a blackbird burst into song, and before Drumsheugh crossed the threshold of Saunders' house, the first ray of the sun had broken on a peak of the Grampians.

MacLure left the bedside, and as the light of the candle fell on the doctor's face, Drumsheugh could see that it was going well with Saunders.

“He's nae waur; an' it's half six noo; it's ower sune tae say mair, but a'm houpin' for the best. Sit doon and take a sleep, for ye're needin' 't, Drumsheugh, an', man, ye hae worked for it.”

As he dozed off, the last thing Drumsheugh saw was the doctor sitting erect in his chair, a clenched fist resting on the bed, and his eyes already bright with the vision of victory.

He awoke with a start to find the room flooded with the morning sunshine, and every trace of last night's work removed.

The doctor was bending over the bed, and speaking to Saunders.

“It's me, Saunders, Doctor MacLure, ye ken; dinna try tae speak or move; juist let this drap milk slip ower—ye 'ill be needin' yir breakfast, lad—and gang tae sleep again.”

Five minutes, and Saunders had fallen into a deep, healthy sleep, all tossing and moaning come to an end. Then MacLure stepped softly across the floor, picked up his coat and waistcoat, and went out at the door. Drumsheugh arose and followed him without a word. They passed through the little garden, sparkling with dew, and beside the byre, where Hawkie rattled her chain, impatient for Bell's coming, and by Saunders' little strip of corn ready for the scythe, till they reached an open field. There they came to a halt, and Doctor MacLure for once allowed himself to go.

His coat he flung east and his waistcoat west, as far as he could hurl them, and it was plain he would have shouted had he been a complete mile from Saunders' room. Any less distance was useless for the adequate expression. He struck Drumsheugh a mighty blow that well-nigh levelled that substantial man in the dust and then the doctor of Drumtochty issued his bulletin.

“Saunders wesna tae live through the nicht, but he's livin' this meenut, an' like to live.

“He's got by the warst clean and fair, and wi' him that's as good as cure.

“It' ill be a graund waukenin' for Bell; she 'ill no be a weedow yet, nor the bairnies fatherless.

“There's nae use glowerin' at me, Drumsheugh, for a body's daft at a time, an' a' canna contain masel' and a'm no gaein' tae try.”

Then it dawned on Drumsheugh that the doctor was attempting the Highland fling.

“He's 'ill made tae begin wi',” Drumsheugh explained in the kirkyard next Sabbath, “and ye ken he's been terrible mishannelled by accidents, sae ye may think what like it wes, but, as sure as deith, o' a' the Hielan flings a' ever saw yon wes the bonniest.

“A' hevna shaken ma ain legs for thirty years, but a' confess tae a turn masel. Ye may lauch an' ye like, neeburs, but the thocht o' Bell an' the news that wes waitin' her got the better o' me.”

Drumtochty did not laugh. Drumtochty looked as if it could have done quite otherwise for joy.

“A' wud hae made a third gin a hed been there,” announced Hillocks, aggressively.

“Come on, Drumsheugh,” said Jamie Soutar, “gie's the end o't; it wes a michty mornin'.”

“'We're twa auld fules,' says MacLure tae me, and he gaithers up his claithes. 'It wud set us better tae be tellin' Bell.'

“She wes sleepin' on the top o' her bed wrapped in a plaid, fair worn oot wi' three weeks' nursin' o' Saunders, but at the first touch she was oot upon the floor.

“'Is Saunders deein', doctor?' she cries. 'Ye promised tae wauken me; dinna tell me it's a' ower.'

“'There's nae deein' aboot him, Bell; ye're no tae lose yir man this time, sae far as a' can see. Come ben an' jidge for yersel'.'

“Bell lookit at Saunders, and the tears of joy fell on the bed like rain.

“'The shadow's lifted,' she said; 'he's come back frae the mooth o' the tomb.

“'A' prayed last nicht that the Lord wud leave Saunders till the laddies cud dae for themselves, an' thae words came intae ma mind, 'Weepin' may endure for a nicht, but joy cometh in the mornin'.”

“'The Lord heard ma prayer, and joy hes come in the mornin',' an' she gripped the doctor's hand.

“'Ye've been the instrument, Doctor MacLure. Ye wudna gie him up, and ye did what nae ither cud for him, an' a've ma man the day, and the bairns hae their father.'

“An' afore MacLure kent what she was daein', Bell lifted his hand to her lips an' kissed it.”

“Did she, though?” cried Jamie. “Wha wud hae thocht there wes as muckle spunk in Bell?”

“MacLure, of coorse, was clean scandalized,” continued Drumsheugh, “an' pooed awa his hand as if it hed been burned.

“Nae man can thole that kind o' fraikin', and a' never heard o' sic a thing in the parish, but we maun excuse Bell, neeburs; it wes an occasion by ordinar,” and Drumsheugh made Bell's apology to Drumtochty for such an excess of feeling.

“A' see naethin' tae excuse,” insisted Jamie, who was in great fettle that Sabbath; “the doctor hes never been burdened wi' fees, and a'm judgin' he coonted a wumman's gratitude that he saved frae weedowhood the best he ever got.”

“A' gaed up tae the Manse last nicht,” concluded Drumsheugh, “and telt the minister hoo the doctor focht aucht oors for Saunders' life, an' won, and ye never saw a man sae carried. He walkit up and doon the room a' the time, and every other meenut he blew his nose like a trumpet.

“'I've a cold in my head to-night, Drumsheugh,' says he; 'never mind me.'”

“A've hed the same masel in sic circumstances; they come on sudden,” said Jamie.

“A' wager there 'ill be a new bit in the laist prayer the day, an' somethin' worth hearin'.”

And the fathers went into kirk in great expectation.

“We beseech Thee for such as be sick, that Thy hand may be on them for good, and that Thou wouldst restore them again to health and strength,” was the familiar petition of every Sabbath.

The congregation waited in a silence that might be heard, and were not disappointed that morning, for the minister continued:

“Especially we tender Thee hearty thanks that Thou didst spare Thy servant who was brought down into the dust of death, and hast given him back to his wife and children, and unto that end didst wonderfully bless the skill of him who goes out and in amongst us, the beloved physician of this parish and adjacent districts.”

“Didna a' tell ye, neeburs?” said Jamie, as they stood at the kirkyard gate before dispersing; “there's no a man in the coonty cud hae dune it better. 'Beloved physician,' an' his 'skill,' tae, an' bringing in 'adjacent districts'; that's Glen Urtach; it wes handsome, and the doctor earned it, ay, every word.

“It's an awfu' peety he didna hear you; but dear knows whar he is the day, maist likely up—”

Jamie stopped suddenly at the sound of a horse's feet, and there, coming down the avenue of beech trees that made a long vista from the kirk gate, they saw the doctor and Jess.

One thought flashed through the minds of the fathers of the commonwealth.

It ought to be done as he passed, and it would be done if it were not Sabbath. Of course it was out of the question on Sabbath.

The doctor is now distinctly visible, riding after his fashion.

There was never such a chance, if it were only Saturday; and each man reads his own regret in his neighbor's face.

The doctor is nearing them rapidly; they can imagine the shepherd's tartan.

Sabbath or no Sabbath, the Glen cannot let him pass without some tribute of their pride.

Jess had recognized friends, and the doctor is drawing rein.

“It hes tae be dune,” said Jamie desperately, “say what ye like.” Then they all looked towards him, and Jamie led.

“Hurrah,” swinging his Sabbath hat in the air, “hurrah,” and once more, “hurrah,” Whinnie Knowe, Drumsheugh, and Hillocks joining lustily, but Tammas Mitchell carrying all before him, for he had found at last an expression for his feelings that rendered speech unnecessary.

It was a solitary experience for horse and rider, and Jess bolted without delay. But the sound followed and surrounded them, and as they passed the corner of the kirkyard, a figure waved his college cap over the wall and gave a cheer on his own account.

“God bless you, doctor, and well done.”

“If it isna the minister,” cried Drumsheugh, “in his goon an' bans, tae think o' that; but a' respeck him for it.”

Then Drumtochty became self-conscious, and went home in confusion of face and unbroken silence, except Jamie Soutar, who faced his neighbors at the parting of the ways without shame.

“A' wud dae it a' ower again if a' hed the chance; he got naethin' but his due.” It was two miles before Jess composed her mind, and the doctor and she could discuss it quietly together.

“A' can hardly believe ma ears, Jess, an' the Sabbath tae; their verra jidgment hes gane frae the fouk o' Drumtochty.

“They've heard about Saunders, a'm thinkin', wumman, and they're pleased we brocht him roond; he's fairly on the mend, ye ken, noo.

“A' never expeckit the like o' this, though, and it wes juist a wee thingie mair than a' cud hae stude.

“Ye hev yir share in't tae, lass; we've hed mony a hard nicht and day thegither, an' yon wes oor reward. No mony men in this warld 'ill ever get a better, for it cam frae the hert o' honest fouk.”

Drumtochty had a vivid recollection of the winter when Dr. MacLure was laid up for two months with a broken leg, and the Glen was dependent on the dubious ministrations of the Kildrummie doctor. Mrs. Macfayden also pretended to recall a “whup” of some kind or other he had in the fifties, but this was considered to be rather a pyrotechnic display of Elspeth's superior memory than a serious statement of fact. MacLure could not have ridden through the snow of forty winters without suffering, yet no one ever heard him complain, and he never pled illness to any messenger by night or day.

“It took me,” said Jamie Soutar to Milton afterwards, “the feck o' ten meenuts tae howk him 'an' Jess oot ae snawy nicht when Drums turned bad sudden, and if he didna try to excuse himself for no hearing me at aince wi' some story aboot juist comin' in frae Glen Urtach, and no bein' in his bed for the laist twa nichts.

“He wes that carefu' o' himsel an' lazy that if it hedna been for the siller, a've often thocht, Milton, he wud never hae dune a handstroke o' wark in the Glen.

“What scunnered me wes the wy the bairns were ta'en in wi' him. Man, a've seen him tak a wee laddie on his knee that his ain mither cudna quiet, an' lilt 'Sing a song o' saxpence' till the bit mannie would be lauchin' like a gude are, an' pooin' the doctor's beard.

“As for the weemen, he fair cuist a glamour ower them; they're daein' naethin' noo but speak aboot this body and the ither he cured, an' hoo he aye hed a couthy word for sick fouk. Weemen hae nae discernment, Milton; tae hear them speak ye wud think MacLure hed been a releegious man like yersel, although, as ye said, he wes little mair than a Gallio.

“Bell Baxter was haverin' awa in the shop tae sic an extent aboot the wy MacLure brocht roond Saunders when he hed the fever that a' gied oot at the door, a' wes that disgusted, an' a'm telt when Tammas Mitchell heard the news in the smiddy he wes juist on the greeting.

“The smith said that he wes thinkin' o' Annie's tribble, but ony wy a' ca' it rael bairnly. It's no like Drumtochty; ye're setting an example, Milton, wi' yir composure. But a' mind ye took the doctor's meesure as sune as ye cam intae the pairish.”

It is the penalty of a cynic that he must have some relief for his secret grief, and Milton began to weary of life in Jamie's hands during those days.

Drumtochty was not observant in the matter of health, but they had grown sensitive about Dr. MacLure, and remarked in the kirkyard all summer that he was failing.

“He wes aye spare,” said Hillocks, “an' he's been sair twisted for the laist twenty year, but a' never mind him booed till the year. An' he's gaein' intae sma' buke (bulk), an' a' dinna like that, neeburs.

“The Glen wudna dae weel withoot Weelum MacLure, an' he's no as young as he wes. Man, Drumsheugh, ye micht wile him aff tae the saut water atween the neeps and the hairst. He's been workin' forty year for a holiday, an' it's aboot due.”

Drumsheugh was full of tact, and met MacLure quite by accident on the road.

“Saunders'll no need me till the shearing begins,” he explained to the doctor, “an' a'm gaein' tae Brochty for a turn o' the hot baths; they're fine for the rheumatics.

“Wull ye no come wi' me for auld lang syne? it's lonesome for a solitary man, an' it wud dae ye gude.”

“Na, na, Drumsheugh,” said MacLure, who understood perfectly, “a've dune a' thae years withoot a break, an' a'm laith (unwilling) tae be takin' holidays at the tail end.

“A'll no be mony months wi' ye a' thegither noo, an' a'm wanting tae spend a' the time a' hev in the Glen. Ye see yersel that a'll sune be getting ma lang rest, an' a'll no deny that a'm wearyin' for it.”

As autumn passed into winter, the Glen noticed that the doctor's hair had turned grey, and that his manner had lost all its roughness. A feeling of secret gratitude filled their hearts, and they united in a conspiracy of attention. Annie Mitchell knitted a huge comforter in red and white, which the doctor wore in misery for one whole day, out of respect for Annie, and then hung it in his sitting-room as a wall ornament. Hillocks used to intercept him with hot drinks, and one drifting day compelled him to shelter till the storm abated. Flora Campbell brought a wonderful compound of honey and whiskey, much tasted in Auchindarroch, for his cough, and the mother of young Burnbrae filled his cupboard with black jam, as a healing measure. Jamie Soutar seemed to have an endless series of jobs in the doctor's direction, and looked in “juist tae rest himsel” in the kitchen.

MacLure had been slowly taking in the situation, and at last he unburdened himself one night to Jamie.

“What ails the fouk, think ye? for they're aye lecturin' me noo tae tak care o' the weet and tae wrap masel up, an' there's no a week but they're sendin' bit presents tae the house, till a'm fair ashamed.”

“Oo, a'll explain that in a meenut,” answered Jamie, “for a' ken the Glen weel. Ye see they're juist try in' the Scripture plan o' heapin' coals o' fire on yer head.

“Here ye've been negleckin' the fouk in seeckness an' lettin' them dee afore their freends' eyes withoot a fecht, an' refusin' tae gang tae a puir wumman in her tribble, an' frichtenin' the bairns—no, a'm no dune—and scourgin' us wi' fees, and livin' yersel' on the fat o' the land.

“Ye've been carryin' on this trade ever sin yir father dee'd, and the Glen didna notis. But ma word, they've fund ye oot at laist, an' they're gaein' tae mak ye suffer for a' yir ill usage. Div ye understand noo?” said Jamie, savagely.

For a while MacLure was silent, and then he only said:

“It's little a' did for the puir bodies; but ye hev a gude hert, Jamie, a rael good hert.”

It was a bitter December Sabbath, and the fathers were settling the affairs of the parish ankle deep in snow, when MacLure's old housekeeper told Drumsheugh that the doctor was not able to rise, and wished to see him in the afternoon. “Ay, ay,” said Hillocks, shaking his head, and that day Drumsheugh omitted four pews with the ladle, while Jamie was so vicious on the way home that none could endure him.

Janet had lit a fire in the unused grate, and hung a plaid by the window to break the power of the cruel north wind, but the bare room with its half-a-dozen bits of furniture and a worn strip of carpet, and the outlook upon the snow drifted up to the second pane of the window and the black firs laden with their icy burden, sent a chill to Drumsheugh's heart.

The doctor had weakened sadly, and could hardly lift his head, but his face lit up at the sight of his visitor, and the big hand, which was now quite refined in its whiteness, came out from the bed-clothes with the old warm grip.

“Come in by, man, and sit doon; it's an awfu' day tae bring ye sae far, but a' kent ye wudna grudge the traivel.

“A' wesna sure till last nicht, an' then a' felt it wudna be lang, an' a' took a wearyin' this mornin' tae see ye.

“We've been friends sin' we were laddies at the auld school in the firs, an' a' wud like ye tae be wi' me at the end. Ye 'ill stay the nicht, Paitrick, for auld lang syne.”

Drumsheugh was much shaken, and the sound of the Christian name, which he had not heard since his mother's death, gave him a “grue” (shiver), as if one had spoken from the other world.

“It's maist awfu' tae hear ye speakin' aboot deein', Weelum; a' canna bear it. We 'ill hae the Muirtown doctor up, an' ye 'ill be aboot again in nae time.

“Ye hevna ony sair tribble; ye're juist trachled wi' hard wark an' needin' a rest. Dinna say ye're gaein' tae leave us, Weelum; we canna dae withoot ye in Drumtochty;” and Drumsheugh looked wistfully for some word of hope.

“Na, na, Paitrick, naethin' can be dune, an' it's ower late tae send for ony doctor. There's a knock that canna be mista'en, an' a' heard it last night. A've focht deith for ither fouk mair than forty year, but ma ain time hes come at laist.

“A've nae tribble worth mentionin'—a bit titch o' bronchitis—an' a've hed a graund constitution; but a'm fair worn oot, Paitrick; that's ma complaint, an' its past curin'.”

Drumsheugh went over to the fireplace, and for a while did nothing but break up the smouldering peats, whose smoke powerfully affected his nose and eyes.

“When ye're ready, Paitrick, there's twa or three little trokes a' wud like ye tae look aifter, an' a'll tell ye aboot them as lang's ma head's clear.

“A' didna keep buiks, as ye ken, for a' aye hed a guid memory, so naebody 'ill be harried for money aifter ma deith, and ye 'ill hae nae accoonts tae collect.

“But the fouk are honest in Drumtochty, and they 'ill be offerin' ye siller, an' a'll gie ye ma mind aboot it. Gin it be a puir body, tell her tae keep it and get a bit plaidie wi' the money, and she 'ill maybe think o' her auld doctor at a time. Gin it be a bien (well-to-do) man, tak half of what he offers, for a Drumtochty man wud scorn to be mean in sic circumstances; and if onybody needs a doctor an' canna pay for him, see he's no left tae dee when a'm oot o' the road.”

“Nae fear o' that as lang as a'm livin', Weelum; that hundred's still tae the fore, ye ken, an' a'll tak care it's weel spent.

“Yon wes the best job we ever did thegither, an' dookin' Saunders, ye 'ill no forget that nicht, Weelum”—a gleam came into the doctor's eyes—“tae say neathin' o' the Highlan' fling.”

The remembrance of that great victory came upon Drumsheugh, and tried his fortitude.

“What 'ill become o's when ye're no here tae gie a hand in time o' need? we 'ill tak ill wi' a stranger that disna ken ane o's frae anither.”

“It's a' for the best, Paitrick, an' ye 'ill see that in a whilie. A've kent fine that ma day wes ower, an' that ye sud hae a younger man.

“A' did what a' cud tae keep up wi' the new medicine, but a' hed little time for readin', an' nane for traivellin'.

“A'm the last o' the auld schule, an' a' ken as weel as onybody thet a' wesna sae dainty an' fine-mannered as the town doctors. Ye took me as a' wes, an' naebody ever cuist up tae me that a' wes a plain man. Na, na; ye've been rael kind an' conseederate a' thae years.”

“Weelum, gin ye cairry on sic nonsense ony langer,” interrupted Drumsheugh, huskily, “a'll leave the hoose; a' canna stand it.”

“It's the truth, Paitrick, but we 'ill gae on wi' our wark, far a'm failin' fast.

“Gie Janet ony sticks of furniture she needs tae furnish a hoose, and sell a' thing else tae pay the wricht (undertaker) an' bedrel (grave-digger). If the new doctor be a young laddie and no verra rich, ye micht let him hae the buiks an' instruments; it 'ill aye be a help.

“But a' wudna like ye tae sell Jess, for she's been a faithfu' servant, an' a freend tae. There's a note or twa in that drawer a' savit, an' if ye kent ony man that wud gie her a bite o' grass and a sta' in his stable till she followed her maister—'

“Confoond ye, Weelum,” broke out Drumsheugh; “its doonricht cruel o' ye to speak like this tae me. Whar wud Jess gang but tae Drumsheugh? she 'ill hae her run o' heck an' manger sae lang as she lives; the Glen wudna like tae see anither man on Jess, and nae man 'ill ever touch the auld mare.”

“Dinna mind me, Paitrick, for a” expeckit this; but ye ken we're no verra gleg wi' oor tongues in Drumtochty, an' dinna tell a' that's in oor hearts.

“Weel, that's a' that a' mind, an' the rest a' leave tae yersel'. A've neither kith nor kin tae bury me, sae you an' the neeburs 'ill need tae lat me doon; but gin Tammas Mitchell or Saunders be stannin' near and lookin' as if they wud like a cord, gie't tae them, Paitrick. They're baith dour chiels, and haena muckle tae say, but Tammas hes a graund hert, and there's waur fouk in the Glen than Saunders.

“A'm gettin' drowsy, an' a'll no be able tae follow ye sune, a' doot; wud ye read a bit tae me afore a' fa' ower?

“Ye 'ill find ma mither's Bible on the drawers' heid, but ye 'ill need tae come close tae the bed, for a'm no hearin' or seein' sae weel as a' wes when ye cam.”

Drumsheugh put on his spectacles and searched for a comfortable Scripture, while the light of the lamp fell on his shaking hands and the doctor's face where the shadow was now settling.

“Ma mither aye wantit this read tae her when she wes sober” (weak), and Drumsheugh began, “In My Father's house are many mansions,” but MacLure stopped him.

“It's a bonnie word, an' yir mither wes a sanct; but it's no for the like o' me. It's ower gude; a' daurna tak it.

“Shut the buik an' let it open itsel, an' ye 'ill get a bit a've been readin' every nicht the laist month.”

Then Drumsheugh found the Parable wherein the Master tells us what God thinks of a Pharisee and of a penitent sinner, till he came to the words: “And the publican, standing afar off, would not lift up so much as his eyes to heaven, but smote upon his breast, saying, God be merciful to me a sinner.”

“That micht hae been written for me, Paitrick, or ony ither auld sinner that hes feenished his life, an' hes naethin' tae say for himsel'.

“It wesna easy for me tae get tae kirk, but a' cud hae managed wi' a stretch, an' a' used langidge a' sudna, an' a' micht hae been gentler, and not been so short in the temper. A' see't a' noo.

“It's ower late tae mend, but ye 'ill maybe juist say to the fouk that I wes sorry, an' a'm houpin' that the Almichty 'ill hae mercy on me.

“Cud ye ... pit up a bit prayer, Paitrick?”

“A' haena the words,” said Drumsheugh in great distress; “wud ye like's tae send for the minister?”

“It's no the time for that noo, an' a' wud rather hae yersel'—juist what's in yir heart, Paitrick: the Almichty 'ill ken the lave (rest) Himsel'.”

So Drumsheugh knelt and prayed with many pauses.

“Almichty God ... dinna be hard on Weelum MacLure, for he's no been hard wi' onybody in Drumtochty.... Be kind tae him as he's been tae us a' for forty year.... We're a' sinners afore Thee.... Forgive him what he's dune wrang, an' dinna cuist it up tae him.... Mind the fouk he's helpit .... the wee-men an' bairnies.... an' gie him a welcome hame, for he's sair needin't after a' his wark.... Amen.”

“Thank ye, Paitrick, and gude nicht tae ye. Ma ain true freend, gie's yir hand, for a'll maybe no ken ye again.

“Noo a'll say ma mither's prayer and hae a sleep, but ye 'ill no leave me till a' is ower.”

Then he repeated as he had done every night of his life:

“This night I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

And if I die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.”

He was sleeping quietly when the wind drove the snow against the window with a sudden “swish;” and he instantly awoke, so to say, in his sleep. Some one needed him.

“Are ye frae Glen Urtach?” and an unheard voice seemed to have answered him.

“Worse is she, an' suffering awfu'; that's no lichtsome; ye did richt tae come.

“The front door's drifted up; gang roond tae the back, an' ye 'ill get intae the kitchen; a'll be ready in a meenut.

“Gie's a hand wi' the lantern when a'm saidling Jess, an' ye needna come on till daylicht; a' ken the road.”

Then he was away in his sleep on some errand of mercy, and struggling through the storm. “It's a coorse nicht, Jess, an' heavy traivellin'; can ye see afore ye, lass? for a'm clean confused wi' the snaw; bide a wee till a' find the diveesion o' the roads; it's aboot here back or forrit.

“Steady, lass, steady, dinna plunge; i'ts a drift we're in, but ye're no sinkin'; ... up noo; ... there ye are on the road again.

“Eh, it's deep the nicht, an' hard on us baith, but there's a puir wumman micht dee if we didna warstle through; ... that's it; ye ken fine what a'm sayin.'

“We 'ill hae tae leave the road here, an' tak tae the muir. Sandie 'ill no can leave the wife alane tae meet us; ... feel for yersel” lass, and keep oot o' the holes.

“Yon's the hoose black in the snaw. Sandie! man, ye frichtened us; a' didna see ye ahint the dyke; hoos the wife?”

After a while he began again:

“Ye're fair dune, Jess, and so a' am masel'; we're baith gettin' auld, an' dinna tak sae weel wi' the nicht wark.

“We 'ill sune be hame noo; this is the black wood, and it's no lang aifter that; we're ready for oor beds, Jess.... ay, ye like a clap at a time; mony a mile we've gaed hegither.

“Yon's the licht in the kitchen window; nae wonder ye're nickering (neighing).... it's been a stiff journey; a'm tired, lass.... a'm tired tae deith,” and the voice died into silence.

Drumsheugh held his friend's hand, which now and again tightened in his, and as he watched, a change came over the face on the pillow beside him. The lines of weariness disappeared, as if God's hand had passed over it; and peace began to gather round the closed eyes.

The doctor has forgotten the toil of later years, and has gone back to his boyhood.

“The Lord's my Shepherd, I'll not want,” he repeated, till he came to the last verse, and then he hesitated.

“Goodness and mercy all my life

Shall surely follow me.

“Follow me ... and ... and ... what's next? Mither said I wes tae haed ready when she cam.

“'A'll come afore ye gang tae sleep, Wullie, but ye 'ill no get yir kiss unless ye can feenish the psalm.'

“And ... in God's house ... for evermore my ... hoo dis it rin? a canna mind the next word ... my, my—