This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Boy Scouts Afoot in France

or, With the Red Cross Corps at the Marne

Author: Herbert Carter

Release Date: November 15, 2014 [eBook #47358]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOY SCOUTS AFOOT IN FRANCE***

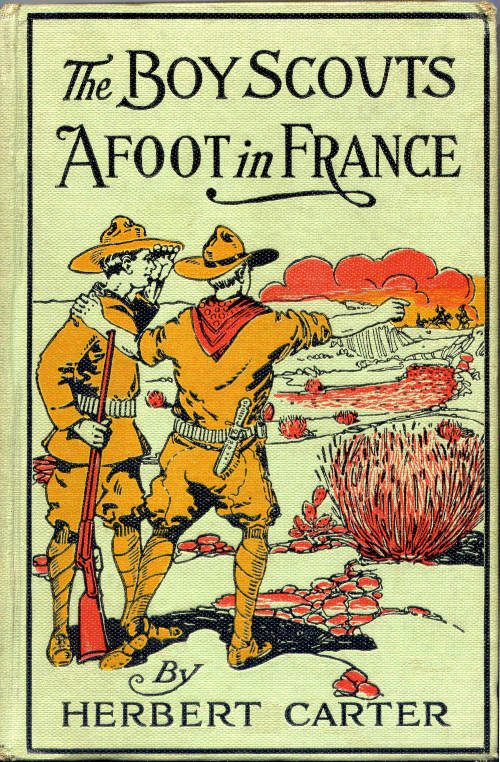

Those boys would never forget that furious race. It was impressed on their memories after a fashion that time could not efface.

Page 60.

OR

With the Red Cross Corps at the Marne

By HERBERT CARTER

Author of

“The Boy Scouts at the Battle of Saratoga”

“The Boy Scouts Through the Big Timber”

“The Boy Scouts on Sturgeon Island”

“The Boy Scouts in the Blue Ridge”

“The Boy Scouts’ First Camp Fire”

“The Boy Scouts in the Rockies”

“The Boy Scouts on the Trail”

“The Boy Scouts on War Trails in Belgium”

“The Boy Scouts Down in Dixie”

“The Boy Scouts in the Maine Woods”

“The Boy Scouts Along the Susquehanna”

Copyright, 1917

By A. L. Burt Company

“Well, here we are, up the River Schelde at last, and landing at old Antwerp, boys.”

“Yes, that’s right, Thad, and glad to set foot again on solid ground, after that long trip over the North Sea from Rotterdam, away up in Holland.”

“Of course Bumpus is happy, because he expects to join his mother here at the Sanitarium. We all hope you’ll find her much improved, and ready to start for the good old United States, where peace hangs out and folks don’t dream of lining up in battle array like they’re all doing over here in Europe.”

“Thank you, Thad, I am hugging that same wish to my heart myself right along. Just as soon as we can get some sort of vehicle let’s head for the Institution. I’m in a cold sweat for fear something may have happened. It’s a long time since I heard from my poor mother, you know, boys.”

“Yes, you worried all the time we were drifting down the Rhine on that boat we chartered; and Bumpus, I really believe you’ve been thinking of your mother every hour we spent trying our best to get through Belgium, while running into so many snags at every turn that we finally had to go into Holland and take a steamer here.”

“I admit all you say, Giraffe, I humbly do, for you see she’s the only mother I’ve got. But please look for a vehicle, Thad, or you, Allan. I have cold spells, and then flashes of fever by turns.”

“I’m thinking we may have considerable trouble finding any sort of conveyance, because most horses and cars have been seized by the Belgian military authorities. But we’ll do our best, and money generally talks over here as it does in America.”

There were four of the boys in the bunch. All of them wore more or less faded khaki suits, and had battered campaign hats on their heads, which facts told louder than words could have done that they must belong to that famous organization known as the Boy Scouts of America.

First, to introduce them in as short a space as possible, for the convenience of any reader who may be making their acquaintance for the first time, let it be set down that their names were Thad Brewster, Allan Hollister, “Bumpus” Hawtree and “Giraffe” Stedman.

The Hawtree lad was once in a while known as “Cornelius Jasper”; and on rare occasions he who answered to the family name of Stedman, a lanky chap in the bargain, had “Conrad” tacked to his address; but never when in the society of his comrades of the baseball or football field, or when scouring the country in the company of those who wore the khaki.

These lads were all members of the Silver Fox Patrol connected with Cranford Troop of Boy Scouts; and the enterprising town in which they lived was located in the eastern part of the States.

They had seen many strange sights, and passed through a host of experiences, both singular and thrilling, as any one who has read previous volumes in this series can attest. Perhaps the most remarkable of all their exploits had come to them during this summer upon finding themselves in Germany when the Great War suddenly broke out, and they had the time of their lives trying to get past the fiercely contending Belgian and Teuton armies, in the endeavor to reach the city of Antwerp on the River Schelde.[1]

A few words with regard to the reason for their being abroad would perhaps not come in amiss here, in order that the reader may understand what follows: It had come about that Mrs. Hawtree, being ill, was recommended to go to Antwerp and stop for a season at a famous Sanitarium, where celebrated physicians who had made a specialty of such cases as hers would very likely be able to render her more or less assistance, possibly effect a permanent cure.

Mr. Hawtree, being unable to accompany his wife on account of pressing business engagements, sent his son instead. As Bumpus was usually an “easy mark” on account of his good nature, it was arranged that his faithful chums, Thad, Allan and Giraffe, accompany him, half of the expense being paid by the Hawtrees.

So they had left the lady in Antwerp, and then started out to put a long-cherished plan into operation. At a certain city on the Upper Rhine they chartered a boat, aboard which they began to descend the wonderfully beautiful river, admiring the famous old castles on its banks, and having a “simply glorious time,” as Bumpus himself always put it.

Then came the thunderbolt when they learned how war had suddenly broken out, with the great German military machine pouring troops over the Belgian border by tens and hundreds of thousands, thinking to catch France totally unprepared, so that Paris could be taken, and the country forced to its knees.

The boys had hastily abandoned their cruise on the Rhine, and, securing an old rattletrap of a car, for fear a good one might be taken from them, they started for the border, in hopes of getting across, and finally reaching Antwerp.

But after many adventures they had finally been forced to change their plans, retreating to Holland instead, and then coming around by way of the North Sea. So here they were, safe at last at their destination, and glad to know that they had broken down all obstacles to their progress.

Thad Brewster was the leader. He held the position by virtue of his commanding nature, as well as the fact that he was at the head of the Silver Fox Patrol, and indeed often served as scout-master of the troop in the absence of the duly authorized gentleman who occupied that lofty office.

On his part Allan Hollister could claim to be the best-posted member of the troop when it came to a knowledge of woodcraft and an acquaintance with the denizens of the wilderness in the shape of fur, fin and feather, for he was a Maine boy, and that stands for a great deal.

Giraffe, he of the long “rubber-neck,” was a master hand at several things, though it must be admitted that he took more pride in his ability to start a fire in a dozen different ways than concerning anything else he did.

As for Bumpus, he did not claim to excel in anything, unless it was a remarkably good judgment with various kinds of food and ways in which to prepare them so as to arouse the appetites of his mates.

It happened that they found little difficulty in securing the services of a driver, since they had made up their minds not to scorn any sort of vehicle so long as it got them to the Sanitarium on that August morning.

As they bundled in with their scanty luggage and started off from the quay at which the steamer from Rotterdam had tied up, the boys naturally found themselves keenly interested in all they saw. Antwerp under war conditions was quite a different city from the rather quiet, staid place they had thought it before. Indeed, all of them admitted that it fairly seethed with excitement, and was full of most thrilling sights just then.

Men in soldierly garments could be seen on the streets, all apparently hurrying toward some central point of mobilization. Twice the boys heard the clatter of many horses’ hoofs as their carriage was drawn hastily aside to allow a battery of field-pieces to pass by with a whirl. These were possibly heading for the front, where the Belgians still heroically resisted this forced invasion of their country by their powerful and unscrupulous northern neighbor, one of the countries guaranteeing the neutrality of Belgium at that.

Cars shot this way and that like hurrying meteors. Often they could see that officers of rank occupied them. For all they knew the boys may have been looking on the King of the Belgians himself, though it was more probable that Albert kept much closer to the firing line while his men were sacrificing themselves for the national honor.

“Honest to goodness!” Giraffe was heard saying as they surveyed all these interesting sights, turning their heads constantly from side to side like boys in a “three-ringed” circus. “I kind-a hate to get away from here while things are booming this way. It’s a chance in a life-time to see what war means. I seem to feel something strange stirring within me every time I think of how these brave Belgians are trying to hold the Kaiser’s terrible military machine in check, and somehow I imagine it may be hero-worship that ails me.”

“Huh!” grunted the more practical Bumpus, “more’n likely it’s that cucumber salad you had aboard the steamer for supper last night. It gave me a few spasms myself, and you know I’m nearly fool-proof.”

“Well, there’s the Sanitarium ahead of us,” suggested Thad just then, and of course Bumpus had nothing more to say; though his face again assumed that anxious expression so foreign to its usually calm and satisfied condition.

Holding the vehicle at their service, the four boys hastened to enter the grounds of the big and famous institution. Somehow it struck Thad as though there was lacking considerable of the bustle he had noticed when there before. He fell to wondering what that sign could mean, and if poor Bumpus was to have a bitter disappointment after all his trouble.

Gaining the office they found that instead of the pompous individual whom they had met before, a rather obscure-looking party now held forth, undoubtedly a subordinate. Bumpus hastened to push forward, and they saw him talking with this party, who evidently was able to comprehend and speak English. Indeed, many of the patients came from foreign parts, even distant America, so it was only natural that those in charge must be linguists.

Bumpus looked as though far from happy, Thad noticed. The official, after satisfying himself that the stout, red-cheeked boy was the party he claimed to be, had produced a letter, which he handed over. This Bumpus had opened with trembling hands and was seen to devour greedily.

“There’s something gone wrong, take it from me,” remarked Giraffe, as they saw the other starting toward them, still gripping his letter and looking pretty pale. “What’s hit you, Bumpus?” he continued, not coldly, but really with a touch of brotherly sympathy in his voice.

“Oh! what do you think!” exclaimed Bumpus, bitterly; “my mother has gone to Paris with the head doctor, most of the staff and some of the patients, and she wants me to join her there.”

When Bumpus put up this piteous plaint the other scouts exchanged glances. Here was an unexpected complication that faced them, a puzzling riddle that would have to be solved.

Undoubtedly, when the news reached Antwerp that the great Kaiser had sent his terrible army into Belgium, it was realized that although King Albert’s little army might offer a desperate defense that would cover them with immortal fame, there would be but one end to such an uneven struggle. The Belgians might inflict more or less sanguinary losses on the Teuton host, but the machine-roller would eventually overwhelm them, and even Antwerp must fall into the hands of the invaders. And so the managers of the famous Spa had concluded that it would be just as well if they changed their location. They had a companion Cure in Paris, as the boys well knew, and, accordingly, the entire faculty, together with the trained nurses and most of the rich patients as well, had taken their departure some time before.

If, indeed, Paris were seriously threatened by the Germans, it might be like jumping from the frying-pan into the fire. At least the step had been taken, and here was Bumpus looking aghast at the idea of trying to follow his mother, when the whole of Northern France must be seething with war preparations, trains taken over for military purposes, private cars commandeered, and every available horse drafted into the service of the government.

No wonder, then, that Giraffe presently broke out in his explosive way:

“Gee whiz! Here’s a pretty kettle of fish, now!” he ejaculated. “Your mother is in Paris, it seems like, just when the Kaiser’s army is heading that way hot-footed. And she asks you to follow after her, does she, Bumpus? Whew! I can see a bunch of fellows I know breaking into a lot of new trouble trying to dodge a million fighters, more or less. But remember. Bumpus, we’re bound to stick to you whatever happens.”

The party addressed gave Giraffe a look of affection. He could not trust his voice to utter a single word just then, being so completely overcome with emotion, brought on by his bitter disappointment.

As usual, they turned to Thad. When things all went wrong it was queer how these boys of the Silver Fox Patrol placed their dependence on Thad Brewster to guide them out of the wilderness; and rarely had he failed them in an emergency.

“We might be able to make it,” the leader told them, seriously, as though he had been weighing the chances in his mind and already reached a decision; “that is, if things favored us about getting away from here. We ought to go to the railway station at once and see when the first train for Paris starts.”

“But, from all accounts we’ve had, the Germans are already far over the border, and there is desperate fighting going on in a dozen places on French soil,” observed the cautious Allan. “I’m mentioning this fact, not because you’ll find me hanging back whatever you decide to do, but only to get the situation clear in our minds before we take the jump.”

“You’ve got an idea of your own, I take it, Allan?” suggested Thad quickly.

“Well, since we’ve come all the way from Rotterdam by sea and found the going good, what’s to hinder our looking up a boat starting that would carry us to Calais, Dunkirk or Boulogne? It strikes me that if we did manage to land at one of those seaports we’d stand a much better chance of getting through to Paris over the railroad than by coming down here from Belgium.”

“A bright thought, Allan,” admitted Thad, “so let’s climb aboard our rig and scurry back to the docks again, to inquire about the departure of southbound steamers.”

They were speedily hastening back to the river, where those bustling scenes were hourly taking place, for even at this early date every boat leaving for London was packed to its capacity with fugitive tourists trying to get out of the war-stricken country.

Upon inquiry the boys found that they were up against a disappointment. A boat had left only an hour before for Boulogne; indeed, they remembered seeing it passing down the Schelde as they neared the docks. There would not be another bound for a port in France for three days, as most of the vessels were being impressed into the cross channel service just then, heading for England.

Realizing that there was no help for it, Thad suggested that they give up the scheme of going by sea. That long delay was terrible to even think of, and Bumpus could never stand idling his time away when he wanted so much to be on the move.

It was thereupon decided that they seek the railway gare and board the first train that left for Paris. Of course this meant they would have to take great risks, for it could be understood that there was no telling what delays they were likely to face. Still, they had no choice in the matter, unless they chose to cross to London and take chances of being able to reach France in that roundabout way.

Shortly afterward they drove up to the railway gare and dismissed their driver. Here, as everywhere, they found things in the utmost confusion. Every uniformed man was being besieged by a score of wild-eyed persons all wanting to know how soon their train would start, and if there was any hope that it might reach the destination for which it was billed. They had the poor servants of the company almost frantic with trying to pacify them and be civil at the same time.

Thad went about the business in his customary cool, deliberate fashion. First, he learned that a train would actually start for Paris within the hour, though the official who gave him this information merely shrugged his shoulders in an eloquent way when asked whether there was any chance of its reaching the French capital.

Next Thad booked himself and three chums for the journey. They would have to share the third-class compartment with a number of other fugitives, all wild to shake the dust of Belgium off their shoes before those terrible Germans overran the whole country. This, however, did not bother the boys, for they were accustomed to camping out and taking things as they found them. A little crowding was to be expected under such remarkable conditions as prevailed at such a time as this. All of them said they could stand it if the other people were able to endure the crush.

When, later on, the signal was given for the heavily laden train to start, there were numerous persons who had not been able to find accommodations aboard. This came through the ever-growing desire to get away from the city which undoubtedly sooner or later would hear the crashing detonations of the monster mortars that had already smashed the steel-domed defenses of Liege and Namur.

“Well, this is what I call rushing things some,” observed Giraffe, as he looked out from the window near his elbow and saw that they were already leaving the environs of the Belgian seaport behind them. “It isn’t as much as two hours ago that we landed here expecting to pick up Bumpus’ mother and then take passage across the English Channel to London, yet here we are heading right into trouble again, and like as not with a good chance of seeing more fighting than fell to our share before.”

As the minutes continued to glide by and they kept going at a good pace the boys began to hope they might by great luck manage to get by the scene of hostilities without being held up. Bumpus looked at his little nickel watch ever so often. No doubt the time dragged with him as never before, for his faithful heart must be filled with misgivings concerning his sick mother.

Thad, always observing, saw how the boy was worrying, and he several times uttered words of cheer that were calculated to buoy the other’s hopes up more or less.

“Take courage, Bumpus,” he told him, “and look back at our record when you feel despondent. We have always managed, somehow or other, to accomplish whatever we set out to do, you’ll remember. No matter how difficult the task may have seemed, we have been highly favored by good fortune. And we’ll come through this time with colors flying.”

“I ought to be ashamed to let myself have a single doubt, Thad,” Bumpus frankly admitted, as he turned his eyes upon the leader in whom he had such implicit faith, “when right now I’ve got the backing of the best pards that ever donned the khaki. Yes, I’m going to shut my teeth hard together, and tell myself that we’ve got to get to Paris, no matter if a whole German army corps stands in the way.”

“Shucks! I should say so,” Giraffe hastened to remark, for he had been listening to all that went on in spite of the jabbering of other inmates of the compartment, mostly French people hastening back home. “And, say, a railway train isn’t the only means of travel in these enlightened days; there are cars, and even aeroplanes, if you must come to it; though it’d have to be a buster of a heavier-than-air machine that could tote Bumpus fifty miles across country, I reckon.”

They talked from time to time as they continued to progress over the low country that lies toward the border from Antwerp, where canals seemed to predominate; and the boys were often reminded of the Dutch lands that had been reclaimed from the sea by the erection of the great dikes to shut the water out of Flanders.

They knew that as the minutes passed they were undoubtedly drawing closer to that region where trouble would possibly be lying in wait for them, if it came about that they were fated to be held up on their journey to the French capital.

Hence every time the train slackened speed Bumpus would glue his eyes on the landscape as seen through the open window, just as if he more than half-expected to discover a horde of Uhlans, with their lances and pennons and prancing horses, waiting to take the fugitives into camp as prisoners.

Finally as the afternoon began to wear away they did come to a halt in a small town. Thad announced that he believed they must now be on the border between Belgium and France. Here, if anywhere, they ought to be able to learn what the immediate future held in store for them.

A guard unlocked the door of their carriage. Thad could see that the man was looking displeased, as he made gestures with his hand to indicate that they must all get out.

“Of course they mean to search us for prohibited articles, such as tobacco and spirits,” Allan went on to say, as they hastened to comply with the order.

“I hope that’s the extent of the trouble,” ventured the doubting Bumpus; “but I’m awfully afraid this means we’re going to find ourselves in the soup. I wish we could coax that fellow to give us a little information; try him, won’t you, Thad?”

There was only one way of making the guard talk, and Thad understood the value of a generous tip; so he managed to slip a coin in the willing palm of the uniformed man, and then asked him something.

Thad had picked up a little French and could manage to make himself understood. Then again the guard would readily guess just what each and every passenger aboard the detained train must be anxious about, for it concerned their chances of continuing the journey into France.

While their leader was holding this animated talk with the guard, supplemented on the part of the native with sundry expressive shrugs that spoke more eloquently than words, the other three boys stood near by, holding their luggage, and wondering what fortune had in store for them next. So many strange things had happened to the party since coming across the sea that they were rapidly getting to a point where nothing surprised them very much.

Presently Thad joined them. His face looked grave, and poor Bumpus groaned as he anticipated the worst.

“This train is going to be abandoned right here, boys,” Thad told them. “They had information that the Germans have overrun the country it must pass through, and there would be no hope of our getting to Paris. We’ve got to try some other way around.”

Upon hearing this unpleasant news poor Bumpus looked broken-hearted. He seemed to see a host of obstacles confronting him. Paris must have been something like a thousand miles away just then, according to his enlarged view.

“Just like the luck,” he sighed desolately; “things were moving along too fine to last. I had a sneaking idea in my mind something was bound to blow up before long. What under the sun will we do, Thad?”

“Not give up our plan of getting to Paris, for one thing,” replied the leader firmly, with that determined look on his face the others knew so well.

“Hurrah!” exclaimed Giraffe; “that’s the stuff I like to hear! Nil desperandum it is, Bumpus, and we’ll carry it out on that line if it takes all the balance of the summer. Grant said that, but any fellow with a backbone can feel it.”

“First of all,” continued the practical Thad, “I’m meaning to skirmish around some more and find out what can be done. You see, all the passengers have been pulled out of the carriages. Listen to them babble, will you? They are mostly French, and as excitable as wildfire. Everybody wants to get away from the border here in a hurry. Their dear old France lies just over yonder, and they’re bound to travel if it has to be on foot.”

“Oh, my stars!” ejaculated Bumpus, and then he stopped short, remembering that much as he disliked walking any great distance, he should be the last one of the quartette to complain now, for it was his errand that beckoned them on to Paris.

They immediately bestirred themselves. Each fellow was to mingle with the bustling passengers and pick up any and all information possible. Since they knew so little of the language it was hardly likely that Allan, Bumpus or Giraffe would meet with much success; but at least they would be doing their best.

As usual, they depended a great deal on Thad. He had a happy faculty for doing things; moreover, in this case, he was better fitted for catching snatches of conversation on the part of the voluble French people than any one of his comrades.

About ten minutes later Thad made signals to his chums, on catching their eyes, bidding them join him. This they did only too gladly, for up to that moment none of the trio had learned anything worth mentioning.

“It’s going to be all right, I guess,” Thad told them first of all.

“Then you’ve heard of a train we can take, eh?” queried Bumpus eagerly, while a thankful glow began to appear in his eyes.

“Yes,” replied the other; “it seems there’s another road tapping this place that leads to Calais, which, you know, is on the Channel, and the terminus of a boat line coming from Dover over in England.”

“Sure thing,” remarked Giraffe; “and we figured that since England has butted into this war game she must be sending her little army across the Channel, or the Straits of Dover that way, to help her ally France hold the Kaiser in check.”

“Well, they have a great need of every kind of car at Calais, it seems, passenger and freight, to carry men and munitions from there into the interior. So there has been made up a long train of empties that is going to start across country right away, aiming for Calais. And the railway people here have made arrangements to carry all those who want to head that way, if they promise not to kick at the poor accommodations.”

“Well, any port in a storm,” said Giraffe; “we’ll shut our eyes and go in a cattle van if necessary and not say a single word.”

“Only too glad of the chance,” added Bumpus gratefully; “because once we get to Calais we’ll be out of the line of the invading German army; and it ought to be a whole lot easier for us to make Paris from that point than away up here on the border of Belgium.”

“Yes, it would seem so,” Thad added, with a wrinkle across his forehead; as if even at that time he might be having a faint vision of the terrible difficulties they were destined to meet later on while trying to accomplish their object.

“Lead us to it, Thad,” implored the impatient Giraffe.

Already they could see that some of the excited passengers had commenced to move away. The word was being passed along the line that if they chose to head for the city on the Channel there was an opportunity offered, and few, if any, declined the opening, for they were fairly wild to get deeper into their native country.

When the four American scouts, a little later on, found themselves at another station and gazing upon a long string of traffic vehicles they could not keep from exchanging smiles.

It certainly looked as though already the sudden and violent demands made upon all the railways of Northern France for transportation on account of the mobilization of the troops, with their batteries, and horses, had caused a tremendous drain on their limited resources. They did not have these things “down pat” to the minutest detail, as in Germany, where every man, young and old, knew exactly what was expected of him when a certain order went forth, and the whole nation moved like a gigantic machine, in unison.

The cars were of a polyglot type. There were a few “carriages” as they call the passenger cars across the sea, some first-class, others descending the scale rapidly until they reached the lowest depth of unpainted transportation vehicles, no doubt taken hurriedly from the repair shops. So long as they were apparently sound, and would not break down under a strain, they had been drafted into service.

Besides these there were numerous freight vans, much shorter than even the ordinary open flat cars seen on all American railways. Box cars are not in great use abroad, the goods being covered with heavy tarpaulins instead.

Already most of the carriages had been reserved for the women and children. Little did the four boys care about this. The day was pretty hot, and the sun beamed down from a clear sky, but they were well used to this sort of thing, and had no thought of venturing the first complaint.

“Pick out as solid a van as you can find, Thad,” remarked Bumpus, as they started to walk along this string of antequated traffic carriers.

“Yes, please do,” Giraffe chuckled, “for the sake of Bumpus here, who needs to have things good and strong when he travels. No ordinary coach will do for a fellow of his heft. How about that third van, Thad; it looks as if it might be a fair article?”

Apparently the patrol leader thought the same himself, for he proceeded to climb aboard, after tossing his bag and other “duffle” ahead of him. The others copied his example without delay. Men were boarding the train all along the line, picking out their locations as the whim moved them. There was more or less laughter, and no doubt they joked with one another in their native tongue; for never before had the majority ever deigned to travel upon cattle and goods vans.

Men in uniform bustled around to hasten things. From this Thad judged that there had a hurry call come for the means of transportation over at Calais, where possibly British troops and munitions and batteries were landing daily, and must be taken to the front in haste, for the German invasion threatened Paris by now.

“Here we go,” sang out Giraffe, presently; “that must have been the signal from the man in the motor ahead, to start the string moving. Yes, we’re off at last, and over the border in France.”

Bumpus had managed to settle himself upon his bag, and was looking fairly comfortable, though that anxious expression did not leave his round face entirely.

The long and singularly mixed train pulled out of the border town. People waved after it, for there was such a tingle of excitement in the air these days all over the land that few could settle down to doing any ordinary business. The younger men had rushed off to mobilization centres, and were even now fighting valiantly on the front line, in the endeavor to delay the forward push of the Teuton host, until the defences of Paris could be strengthened. And while the hearts of fathers and mothers went out to the boys in the French army in blue, at this early stage of the great war they did not doubt but that the invaders would be soon driven back to their Northern country.

While at the border town Giraffe had particularly noticed a man whom he vowed paid unusual attention to them. A number of times the boy had declared the other hung around as though trying to listen to what they might be saying. And really Allan himself confessed that the mysterious fellow did have some of the ear-marks of a spy, or secret agent.

Giraffe had made up his mind about that. He vowed the other was a German spy who foolishly believed they must be English boys, and was watching them for some strange purpose. In support of this rather wild statement, Giraffe had even stated that it was already well known how the Germans had planted a host of secret agents all over Belgium and Northern France. Many of these people had lived there for a long term of years, and were in daily touch with their neighbors, picking up all manner of valuable information, which was regularly and systematically forwarded to Headquarters at Berlin, to be entered in ponderous volumes in the archives of the Secret Service, and to be used in event of war.

Every now and then Giraffe would refer to this unknown party. He seemed unable to get the other out of his mind; but then that was Giraffe’s usual way; for once he formed an opinion he always displayed extraordinary obstinacy in sticking to it.

“I only hope that skulker got left at the post, and didn’t make up his mind to go to Calais to find out what was happening there,” he was saying, after taking a good look over their fellow passengers on the van, and failing to discover any sign of the unwelcome one.

Thad and Allan watched the shifting scenery, and commented on its similarity to the Belgian canal country through which they had passed below Antwerp, only that now they met with occasional low hills, and there were times when the motor seemed to be put to its best “licks,” as Allan called it, in order to carry the long train over a rise.

Bumpus still sat there, balancing on his luggage, and possibly trying to count the miles as they were left behind. Whenever he raised his eyes to look steadily toward the southeast there appeared a wistful expression in their depths that did credit to the boy’s faithful heart; because he must be thinking just then of the mother he loved, and how she would be eagerly awaiting his arrival in the French capital.

“We’re coming to another climb, it looks like, Thad,” remarked Allan about this time, as he pointed ahead, and to one side.

The road made something of a bend in order to strike the hill at its lowest point, and consequently they could see what lay before them. Just as Allan had said, the train was soon slowly and laboriously ascending the grade. Giraffe became interested, and soon expressed the opinion that the little motor would have all it could do to drag that heavy train over the crown of the rise.

“Still,” he added thoughtfully, “they seem to have enormous power for such baby engines compared with our big machines, and I guess we’ll make the riffle in decent shape. I’d hate to get stuck here on the slope, and have to wait for help to come along so as to push or pull us to the top.”

He had hardly said this when the boys felt a sudden slackening of the motion.

“Oh! look there, will you?” almost shouted Giraffe, jumping to his feet. “Something’s busted, and the train is going on without these four last vans. There, we’ve commenced to start back down the slope again; and say, it’s too late to jump off! Everybody hold fast, and set your teeth for the worst!”

While Giraffe was saying this the remnant of the train was indeed attaining considerable velocity in its backward rush. Thad knew that a coupling must have broken under the great strain, a no infrequent occurrence across in America.

Of course by now a pandemonium of loud cries and shrieks had broken forth. Some of the more excitable passengers aboard the rear vans acted as though almost ready to hurl themselves out of the open vehicles of transportation. Indeed, Thad just caught one frightened little boy in time to prevent him from jumping wildly.

There was a guard’s van at the extreme rear, and the man in this must have immediately guessed the nature of the accident. Perhaps he had prepared against such a thing, knowing that it was liable to happen.

At any rate he seemed to have some means for putting on the brakes, for while they continued to slip rather swiftly down the grade their progress was not anything like it would have been had the wheels turned unimpeded.

“It’s all right, and nothing is going to happen to hurt us!” called Thad, as he held the struggling French lad fast, despite his efforts to break away.

Although few of those who heard what he said may have exactly understood what the American scout meant, at least his actions were reassuring, and they could comprehend the fact that he must be discounting the danger that menaced them. Then besides they also discovered for themselves that they were not whirling madly down to destruction, as they had at first anticipated would be the case.

Reaching the bottom of the slope the action of the brakes became more pronounced, and presently the fragment of the mixed train came to a stop at the bend. Already had the man in the motor been informed of the disaster that had happened. By looking up the boys could see that the train was backing down toward them.

Everybody breathed easy again. Faces that had turned ghastly white now burned red with the reaction. Some even laughed hysterically, and of course boldly disclaimed anything in the nature of fear. It is always so after the cause of alarm has been effectually dissipated, for people are pretty much alike all over the civilized world.

Giraffe was rubbing his chin, while a shrewd expression stole gradually over his lean and suspicious face. Bumpus was puffing with the excitement, and as red as he could well be. He looked over the edge of the van at the hard ground, with the air of one who might be figuring on how it would feel to be tossed out, and flung on that unfriendly soil.

“Only another little incident in our career over here,” remarked Allan, as though by now they ought to be pretty well accustomed to having thrilling events turn up every little while.

“Well, now, are you quite sure it was just an accident?” asked Giraffe, at which remark all the others immediately turned their eyes on the speaker in surprise.

“What’s bothering you, Giraffe?” spluttered Bumpus, always the slowest to size up a situation when quickness of thought was an asset. “Course a coupling broke and let us slip backwards. It often happens around our part of the country, where the trains have to pull over hills. I’ve seen a coal train dumped in a hollow because of a defective iron coupling pin. And we’re the luckiest fellows going, in the bargain, to have escaped a smash.”

Still Giraffe only wagged that head of his, poised on the longest neck any boy in Cranford could boast, and looked mysterious. Even the way he turned his eyes to the right and to the left added to his solemn manner.

“Go on and tell us what ails you, Giraffe, that’s a decent fellow,” urged Allan Hollister, understanding that unless some one hurried the other along he would keep everlastingly at this business of looking so “knowing.”

“Well, then,” began the tall scout, in a low hoarse tone that he tried to make impressive, “I believe it wasn’t an accident at all, but a deliberate and dastardly attempt at wrecking the train!”

“Whee! who’d want to bother trying to smash such a collection of old traps as these carriages and goods vans are, tell me?” wheezed Bumpus. “You must be dreaming, Giraffe, that’s what.”

“Mebbe I am, Bumpus, mebbe I am,” muttered the other, as he watched the coming of the front part of the long train, “but all the same I’ve got a hunch that there’s something crooked about this thing. You ask who’d want to bother making kindling-wood of these lovely cars? Well, that German spy I warned you about, for one!”

He looked at them triumphantly as he said this. Allan and Thad exchanged glances, though it was hard to tell whether they had been duly impressed or not.

“Now don’t you see, fellows,” the artful Giraffe went on to say, following up his attack while the “iron was hot,” and Bumpus at least was thrilled; “even such a makeshift train as this is going to be mighty useful to the French, for it’ll get a pack of British soldiers to the fighting line much sooner than if they had to walk all the way across country. So wouldn’t it pay a real cunning secret agent of the Kaiser to plot so as to smash things? Why, if he could cause a wreck, and put the old line out of business for twenty-four hours it would count something.”

“Why, it does look like that might be so,” admitted Bumpus; “but I can’t hardly believe any man would put so many innocent lives in danger just to hold back a few cars and vans.”

“But this is war, and we’ve already learned that Germans never hesitate at anything terrible if only they can serve the Fatherland,” Giraffe finished triumphantly.

However, neither Thad nor Allan seemed to be convinced. The former even jumped off and went forward to where some of the men were clustered, endeavoring to repair the damages so that the reunited train could proceed once more. When later on he came back again, it was to tell the others that all was serene, and they were about to proceed, which they soon found to be the case.

“Did you hear anything said about trickery, Thad?” demanded Giraffe, after the hill had been successfully negotiated, and they were once more gliding along at an accelerated pace, perhaps to make up for lost time.

“Not a single word,” the other told him.

“Well, even that doesn’t prove that the thing wasn’t a set-up job,” complained the stubborn Giraffe. “That rascal could cover his work, and make it appear as though it had happened by accident. They’re mighty sly, let me tell you. And I glimpsed him moving about among the people when repairs were being made. Yes, and he even seemed to be having a hand in the work, which I take it was only done to throw off suspicion. But I’m watching him, don’t you forget that. Giraffe’s right on the job. Sooner or later I calculate to trip that spy up.”

Thad was used to hearing the other talk in that strain, for Giraffe invariably went in for things with all his heart and soul. That in a measure accounted for his success in many games in which he took part; and his vim covered up a multitude of minor shortcomings, according to Thad’s way of looking at it.

Of course what the suspicious one had said was not entirely without the bounds of reason. Thad knew that German spies were circulating through Belgium and Northern France by thousands, and taking all sorts of desperate chances in order to do something for their native land. Many of them lived amidst people who had known and respected them for years; and they even carried on extensive business enterprises; but these were only masks for the real reason that kept them exiles from home.

There were no signs of war in the country through which they were now passing, except now and then they glimpsed some man in uniform guarding a bridge. Women, to be sure, were busily engaged caring for the growing crops in the fields; but then in times of peace that is a common sight through most European countries, where they do much of the farm and garden work, while the men go to town with the produce, carry on the voting, and “boss things generally, as our American Indians used to do,” Giraffe had more than once remarked when noticing these things.

In a town they came to, however, there were more stirring sights awaiting them. A regiment was being embarked on a train bound for the front, though just why it had been delayed so long of course the boys never knew. It was a martial spectacle indeed, and one they would often look back to with a thrill. The men were bidding their wives, children, or sweethearts goodbye, well knowing that many of them would never look on those dear faces again.

Those aboard the patched-up train took a deep interest in the going of the reserves to where duty and honor, perhaps a soldier’s grave, awaited them. Being detained on account of the other train that was lying across their track, they could watch all that went on. And when finally it moved off, amidst loud huzzas, and frantic waving of handkerchiefs together with a flood of tender farewells, every one joined in the thrilling shouts, even the four American boys.

Such sights were bound to make a lasting impression on the minds of the young scouts. In years to come they would surely remember them, and in imagination once more see the waving hands, the anxious tear-wet faces of girls and women and children, not to mention the old men; and note how those aboard the departing troop train thrust their hands far out from the windows of the carriages so as to get the very last glimpse of the ones left behind.

But it was over at last. The loaded train bearing brave hearts and valiant souls devoted to the defense of their beloved country had vanished, and those who were bound for Calais could now once more proceed.

“How few of them may ever see their folks again,” said Bumpus, shaking his head sadly; “for we happen to know how men are mowed down like ripe grain before those terrible guns of the Germans.”

“Well, it’s always been going on that way,” added Giraffe, who could survey such things without feeling so “squeamish” as tender-hearted Bumpus, “since the time this world began. Men and animals keep on scrapping, and it’ll be the same to the end of time. Men must fight, and women must weep. But if the women get the vote mebbe they’ll want to do some of the scrapping themselves.”

They understood that by now they were getting well along on their journey, and also if everything went smoothly, in another half-hour or so the slow-moving mixed train could be expected to pull into the seaport whither it was bound.

“Then a whole lot depends on whether we can get transportation to Paris,” Bumpus was telling them, as they discussed this matter.

“Don’t cross a bridge till you come to the same,” warned Giraffe, always confident. “We’ll find a way to get there, make your mind easy, Bumpus. We always do, you know, and that isn’t bragging, either, only telling bald facts.”

Just then the train slackened its speed as though signalled to pull up at the next station, where there was another big crowd awaiting it, perhaps some of whom meant to go on to Calais so as to get across the Channel.

“We’ll stop here for ten minutes, I heard a guard say,” observed Thad; “so if any of you feel like stretching your legs, now’s the time to do it.”

Only Allan took advantage of the opportunity, besides the scout leader. Giraffe and Bumpus continued to sit there and watch all that was going on, at the same time keeping track of such luggage as they possessed.

Giraffe amused himself in trying to mentally figure out what each queer person he chanced to pick out of the jostling throng might be when at home. It was a favorite game with the tall scout, for he had the habit of observation highly developed, as many scouts do, since it grows upon one.

In the midst of his occupation Giraffe received a sudden, violent shock. It really affected him so that he seized Bumpus by the arm and gave that worthy a duplicate thrill.

“Well, wouldn’t that jar you now, Bumpus?” was what Giraffe burst out with. “If you please, there’s our chums talking to beat the band with a man; and what do you think, it’s that crafty German spy. Now what does that mean, I’d like to know?”

Of course, Bumpus was duly impressed with the amazing fact. He sat up and craned his neck in imitation of Giraffe, as well as the difference in their build permitted. Sure enough, the two boys were seen earnestly talking with a man; and just as the watchful Giraffe had declared, he did look a bit mysterious when one came to remember the surrounding circumstances.

But Thad and Allan seemed to have no fear. In fact, they were apparently on very good terms with the other, for while Giraffe looked he saw the man actually shake hands with each in turn, as though he had some reason to be grateful to them.

Well, Giraffe could stand it no longer. He feared some gigantic catastrophe must be threatening the safety of his chums, and that it was high time he hastened to their relief.

Accordingly, he told Bumpus to “sit tight” and watch their luggage.

“I’m bound to find out what all this means, don’t you see?” he explained.

“Go to it, Giraffe; and don’t let that fellow kidnap our chums,” Bumpus told him; and possibly there was a slight vein of sarcasm in the manner of the speaker, though, as a rule, Bumpus was not given to making cutting remarks.

Giraffe quickly joined the others.

“Glad you came, Giraffe,” said Allan, “for you’re just in time to chin in and help a chap in distress. Come, pony up a dollar, and it’ll square the account, both Thad and myself have hit that amount apiece, and he needs three to get back home again from Calais.”

“W-w-why, w-what’s it all about?” gasped Giraffe, almost stunned when he saw all his wonderful castles in the air connected with stealthy German spies tumbling to the ground.

“Nothing out of the way,” explained Thad with a smile, for he understood that Giraffe was up against the fence and pretty nearly “all in.” “You see, this gentleman is Mr. Algernon Smikes. He’s a commercial traveler from London, who, like some other people, chanced to be caught abroad when the war broke out, and has been having a hard time trying to get back to Old England. He’s shown us letters to prove all he says, too; so there’s no doubt about it. His money has run low because of the many delays; and thinking that we were English fellows, he ventured to speak to us. We’ve set him straight about our nationality; but at the same time loaned him eight francs, which he will return when he gets back home again. How about you helping him out, Giraffe?”

Thereupon the drummer started in to beg that Giraffe would pardon him for playing such a contemptible role as that of a “beggar,” something he had never done before in all his life; but the conditions were remarkable, and he did not know how else he could make the home port.

When Giraffe heard him speak he knew instantly that his suspicions had been altogether unfounded, for no German spy could ever assume that cockney brogue. Of course, when he thought the man was watching them in the capacity of a secret agent, he had been only trying to pick up courage enough to “touch” them for a small loan, under the impression that they were also English.

So Giraffe, without a murmur, took out some money and handed it to the other. He probably thought he owed Algernon that much for having so unjustly suspected him of espionage when the poor drummer was only worrying about his inability to cross the Channel after reaching Calais.

They had no further time for engaging in conversation, because the cry went out that the train was about to start. So the boys hastened to join Bumpus, who, in turn, must be told how the “suspect” had turned out to be a most innocent chap indeed. Bumpus grinned a little, upon seeing which Giraffe, with his face much redder than usual, tried to defend his blunder.

“That’s all right,” he said, stoutly; “and I acknowledge the corn. I was mistaken, but, then, nobody can be perfect. I saw my duty, and I did it. Who’s got any fault to find with that policy, tell me? A scout must always keep his eyes open and see what’s going on around him. And he oughtn’t to take things for granted, either. Better to make ten mistakes than to overlook something important just once. And now let’s forget all about it. A dollar was a small sum to pay for such an experience.”

Evidently the lanky chum did not mean to alter his ways, for he was very stubborn, and often remarked that a “giraffe can’t change his spots any more than a leopard.”

Well, they were once more moving along at a fair speed and heading for Calais, on the coast. Allan said it could not be far away, because he could surely detect something like salt air when he sniffed in a knowing way; and the others agreed that this was a fact.

In due time they arrived at Calais. Even before entering the city they could understand that it was altered from the old Calais, where the most exciting events of the day used to be the docking of the over-Channel steamer from London and the arrival and departure of the Paris trains.

It was well along in the afternoon. All sorts of whistles could be heard, as if an unusual number of motors on the railway might be switching and making up extra trains for transporting the troops and batteries and munitions that kept arriving from across the Channel in increasing quantities.

They were soon in the bustle, and it thrilled them to actually see the khaki uniforms of the British “Tommies” everywhere. Up to now, in their wanderings over a part of Belgium, they had never happened to come across any of King George’s soldiers, for the very good reason that none were to be found in that region. But apparently a constant stream must be coming over to join hands with the French in trying to save Paris from the invading host.

Of course all the boys were intensely interested in the wonderful sights they saw on every hand. They drank them in eagerly, and Bumpus was round-eyed with a greedy avidity as he tried to watch both sides of the street while they were going to find a hotel.

At the same time, Thad did not mean to neglect their own mission, although realizing more than ever the stupendous difficulties that were bound to confront them as soon as they tried to find a means for reaching Paris.

Of course every train that pulled out would be filled to overflowing with troops, and if there chanced to be room for any regular passengers those who lived in the French capital would be favored first of all.

Excitement filled the air. Music could be heard, for soldiers will show a certain amount of gaiety even though facing a terrible battle on the morrow. And whichever way one looked it was to see marching men in khaki. Bumpus reckoned that there must be thousands of them in Calais.

“They’ll need to be many times over what the British army boasts, to stand up before the millions of the Kaiser,” Giraffe told him; for, as may be remembered, he had a strain of that same Teuton blood in his veins himself, though claiming to be American to the backbone.

They were fortunate enough to find lodging in a private house, for the hotels could not accommodate another person, being filled to overflowing. When this had been finally accomplished Thad and Allan left the others and sauntered out to discover what chance there was of the journey to Paris being carried through.

They were not long in determining that nothing could be done, that day at least. Bumpus would be grievously disappointed, but it could not be helped. Lots of other folks besides the four chums were being held up there and unable to reach their intended destinations, and Thad soon learned that many of these people were burning with anxiety, since their homes lay directly along the path taken by the German army in making for Paris. Of course they pictured the most terrible things as coming to pass, so the two boys agreed that at least they had something to be thankful for.

They did manage to find a little encouragement, and this led them to hope they might get away on the following morning. A train would be pulling out, and unless another boat came in meanwhile, laden with fresh troops, there might be room for them.

That was a very long night to poor Bumpus. And what made it even worse was the fact that they heard how many thousands of people were quitting the French capital by every sort of conveyance, anticipating that the Germans would soon be surrounding Paris, and another terrible siege would be on like that of ’71. Even the official headquarters and members of the National Legislature had gone south so as to prepare for the worst. And there would always be a possibility that Mrs. Hawtree might have accompanied the staff of the sanitarium to some city in the south of France.

With the coming of morning the boys were astir. Hardly waiting to devour a hasty breakfast, Thad and Allan, together with Giraffe this time, set out to ascertain what the chances might be for an early departure. Luck was with them, since they managed to book for the capital, though duly warned that the train might have to be abandoned long before it reached its intended destination, since one of the three great tidal waves of invaders was said to be threatening communications by way of that very line.

A little thing like that could not deter the boys, and, accordingly, when the train pulled out on schedule time, they were aboard, with Bumpus exceedingly hopeful, though at times also given to serious doubts.

Every mile passed over they knew was taking them closer to where the two hostile armies were maneuvring, each trying to flank the other and gain some decided advantage. At every stop on the way Giraffe could be seen thrusting his head out of the window and evidently straining his hearing.

“I’m almost dead sure I could catch a queer distant rumbling sound when the little wind there is came from out of the southeast,” he remarked after one of these occasions.

“You mean it may have been thunder or big guns working, don’t you, Giraffe?” asked Bumpus, deeply interested himself.

“There’s some sort of a battle on, as sure as you live!” declared the other.

Thad knew he spoke the truth, for he, too, had caught that same low mutter that could mean only one thing, for there was not a cloud in the sky to tell of rain. From the hour the Kaiser’s hosts had crossed the French border there had started a series of earth quakings that would never cease as long as one invader’s foot remained on French soil, no matter if it took years to eject them.

Some time later the train came to a small village and stopped. The boys quickly realized that something had happened, for the guards came along telling the passengers to alight.

“We dare go no further,” Thad told his comrades after listening to what was being said by the chattering throng. “It seems that they’ve got word a portion of one of the great divisions of the German army is overrunning the line ahead of us. It is no longer possible to get to Paris this way. We are just a day too late!”

Bumpus was tugging at Thad’s sleeve immediately.

“But do we have to give it up altogether, Thad?” he asked in a quivering voice. “Isn’t there some sort of way in which we might get around the Germans and come in on Paris from the southwest?”

“Well, we can do our level best and try,” the other assured him. “You know we’ve never been the fellows to give up anything easily, Bumpus. So let’s hustle around to see what sort of conveyance we can strike. And as beggars shouldn’t be choosers we’ll be glad to take whatever comes along.”

Concerning one thing, at least, there was no longer any doubt. They could plainly hear the deep grumble of big guns, while the very earth under them trembled perceptibly with the tremendous shock of the explosions that were miles away.

Undoubtedly the battle was on that must decide the fate of the gay French capital. Von Kluck and those other daring Teuton commanders were converging in toward Paris just as the spokes of a giant wheel draw closer as they approach the hub. If General Joffre, the veteran French leader, could manage through strategy to baffle their designs he would win such immortal fame as no man short of Napoleon had ever attained in the estimation of the French nation.

The boys hunted high and low for some means of transportation. Others were doing the same thing, white of face, as they listened to those dreadful sounds. For aught some of these people knew tens of thousands of Germans might be covering the roads in that section of the country where their beloved homes lay, and their hearts were filled with dire forebodings whenever they thought of the innocent ones toward whom they were endeavoring to hasten.

“We’re mighty lucky to get even this ricketty old rig!” Allan declared as Bumpus and Giraffe were mounting to seats in the wagon. “It’ll help us on our way some miles, and when the horse lays down on us, why we’ll be that much closer to Paris. Then walking is good in the bargain, you know.”

“Oh, I’ll agree to try anything you say, fellows!” Bumpus groaned, “if only it promises to help things along. We must manage to get there by hook or by crook.”

They were duly warned concerning the chances of meeting with detachments of the enemy while on the road; since it must be taken for granted that the moving army would have skirmishers and cavalry forces guarding its flanks, so that the French might not execute a brilliant flank attack and throw the main line into temporary confusion.

It was all very thrilling, especially when they could constantly hear the rumble of artillery far in the distance. The battle that this marked was being fought many miles away; but even at that, they had no reason to believe the country lying between would be free from the invaders.

To Bumpus their progress was terribly slow. True, the poor horse did his best under the lash that the peasant boy in the wooden sabots administered almost without cessation; but at that it seemed a snail’s pace to the impatient boy.

Giraffe advised him to get out and run ahead if he felt that way.

“Time enough to do that when I have to,” Bumpus retorted. “I’m saving myself for an emergency. And from the way this crowbait keeps stumbling along I reckon it’s going to come to a case of shank’s mare right soon with us.”

Thad, however, was bent on keeping their seats just as long as they could. There would be plenty of time for walking when they were forced to that extremity. And he had found other things to attract his attention in the bargain.

Once, when they chanced to be passing over a little rise, he discovered a moving mass of men a couple of miles away. The sun glinted from their accoutrements and disclosed the fact that they must be marching soldiers. When he called the attention of the others to that particular quarter Giraffe, who had extra strong eyesight, immediately declared they were German soldiers without doubt.

“I could tell the French blue right away if I saw it,” he said. “Those men are wearing a sort of greenish-gray uniform, the same as we saw on the Germans up in Belgium when we were trying to make Antwerp. Yes, and they’ve got those odd spiked helmets on that only the Germans fancy.”

The alarming fact that they were now so very close to the oncoming invading army gave them all a new thrill. Even the peasant boy stared at the vision, and looked as though almost heart-broken; for he had doubtless heard terrible stories connected with that other raid through his beloved France, long before he was born, and, of course, he could only fear the worst.

As their road seemed to turn somewhat toward the south just there the boys determined to go on, trusting to luck to see them through. At the worst, if they did come in contact with any troop of raiding Uhlans, they could fall back on the fact of being Americans, and perhaps manage to pass muster.

Among themselves they talked it over as the boy continued to beat the horse and cause him to keep jogging along the winding road. It was soon decided that the moving stream of men they had glimpsed could not belong to the corps that was engaged so fiercely in battle with the Allies defending the approaches to Paris. They must be another section entirely, heading so as to attack the forts around Paris from the west. And it turned out later on just as they had figured, so that the boys could plume themselves on their sagacity.

Just a quarter of an hour afterward Giraffe uttered a cry.

“What’s this I see away over yonder, fellows?” he called out, pointing as he spoke. “Another army in motion and heading so as to come smack up against those chaps in the gray-green uniforms. But say, these troops are in the French blue. Bully for them, they are meaning to make it hot for the Kaiser when he tries to sneak into Paris by the back door. It’s true some of my folks did come from that same Rhine country a long while ago, but now I’m backing the under dog in the fight, and somehow my sympathies seem to be with poor France.”

“But see here, how about us?” ejaculated Bumpus. “Suppose those two armies get to smashing away at each other and with four boys caught between the lines? If that happens, wouldn’t we be apt to find ourselves in a pickle enough? I guess we’d better be looking around for a hiding place. And a deep cyclone cellar’d just about suit me right now.”

“We couldn’t go back if we wanted to,” announced Thad, decisively, “because the Germans must have swarmed across the road a few miles over there where we came from. And so far as I can see, there isn’t much chance of our hiding around here.”

The horse was showing positive signs of giving out. Indeed, the peasant boy had used his whip up in urging the beast on, and, moreover, he could hardly lift his own arm to ply it any longer.

Seeing this, Thad decided that the critical moment had come. They must abandon the wagon and most of their luggage, which latter happened to be exceedingly limited, for by degrees they had gotten rid of most of their things ere this.

When necessity drives there is no use complaining, and these scouts had been through so much in the time they were comrades that by now they could meet an emergency without a grumble. Even Bumpus refrained from complaining. He knew Thad could be depended on to do the very best for them. There must always be a way out of a difficulty if only a fellow was smart enough to find it; and Thad had that happy faculty highly developed.

So they paid off the peasant boy and advised him to start back toward home, even though he might be detained a long time on the road. Once they found themselves afoot again the four boys started off bravely, each carrying a share of what luggage they wished to keep, if it could be managed.

The one hope they hugged to their hearts was that they might come in contact with the advancing French forces rather than be overwhelmed by the Germans. In case the former came about they had arranged their plan of action, meaning to ask only the liberty of keeping on toward Paris, skirting the crowded road and making progress toward their destination.

It struck Thad that the noise of the cannon had grown much louder. This would appear to indicate that the range of the battle must be spreading; also, that it was coming nearer and nearer all the time as fresh detachments took up the fight.

Giraffe sniffed now and then, very much like a war-horse scenting battle-smoke.

“And it certainly does smell like burnt powder, believe me, fellows,” he told his chums. “You can see that the breeze sets from that direction, which is why we hear the guns so plainly. Whee! but there must be heaps of exciting events happening right now, and I’d give something to be able to glimpse the same.”

Strange to say, the others were feeling more or less in the same mood. It must be in the blood for human beings to wish to gaze upon terrible scenes of carnage and valor; for no one had before this ever accused either Thad or Allan of being the possessor of a blood-thirsty spirit. They just realized that history was being made close to them, and that scenes were being enacted every hour that would in future days be immortalized by some skilful painter with his brush. And they were, after all, boys with inquiring minds, as well as having a fair amount of curiosity in their make-up.

It must have been a great temptation, and they surrendered to its wiles. Besides, there was really nothing for them but to either go on or stand still; and no matter which they decided to do, the end would likely be the same. If they were caught between the lines they could hardly expect to get out of the jaws of the trap without seeing something of the conflict that hung in the balance.

“Oh!” suddenly exclaimed Bumpus when there came a peculiarly sharp crash not more than half a mile away from them; “was that an exploding shell, do you think?”

“Just what it was,” asserted Giraffe promptly. “Which shows that things are closing in on us right smart, as our Southern chum, Bob White Quail, would say if he was along now. And, what’s more, we’ll be hearing a lot of the same before we get out of this neck of the woods.”

Bumpus had reason for looking worried. He knew what a terrible amount of damage an exploding shell might accomplish, even when it came from only an ordinary field battery, and he had no wish to offer his pudgy form as a target for the gunner.

They hurried along the road, hoping every minute that a turn would disclose the presence of men in the French blue. A second crash did not make Bumpus feel any more cheerful, especially since this detonation came from still another quarter.

“Do you suppose they’ve glimpsed us and are trying to drop one of those horrible shells right in our midst?” he asked Thad.

Before the scout leader could make any reply there was a sudden wild burst of cannonading from a point close by. Thad guessed the truth at once as if by some instinct. Evidently there must be an advanced French field battery secreted in the region, where it commanded the road over which the Germans were thronging, and this had commenced action. Those several German shells had been dropped just to disclose the position of this battery; its presence being suspected, thanks to some air scout who had passed over previously and communicated the facts to the invading general.

A tremendous din quickly broke out. Guns were fired by the dozen, and the crash of bursting bombs almost deafened the four hurrying boys.

They had good reason to hasten their steps, for to the right and to the left the shells exploded. One tore a great hole in the roadway not a hundred yards in front of them, causing the stones and dirt to fly in every direction.

It was almost impossible to know which way to turn, and as for finding a place of refuge, that was utterly out of the question. There did not seem to be a rod of territory that those searching shells might not fall upon. One place was just as safe as another, since it was all a matter of luck. So Thad kept them on the move, huddled in as small a compass as possible, with the idea of presenting as minute a target to the rain of bombs as they could.

“Listen!” yelled Giraffe as they ran along, with Bumpus puffing like a winded horse dragging a load up hill, “they’re coming right now—the French battery, I mean. Got too hot for ’em where they were, and they’re on the jump for safer quarters. Thad, if we get half a chance, let’s try to hook on to some ammunition caisson! Anything to give those shells the slip! And there the guns come with a whirl!”

It was an inspiring spectacle. The French field battery had done its utmost to inflict more or less damage upon the advancing German hosts, but evidently the time had come for discretion to take the part of desperate valor.

They had no orders to stick it out until every gun was smashed or the enemy had come swarming up to bayonet each reckless gunner. “Those who fight and run away may live to fight another day”; and the policy of these clever Frenchmen was to pester and annoy the oncoming invaders as much as possible in order to delay their progress, since every hour counted in the gathering of a force to defend Paris.

The boys hastened to step aside in order to let the galloping horses and the swinging guns and caissons sweep past. Bumpus looked at the wild way in which they were hastening along the dusty road and gave it up. It would take a much better athlete than he professed to be to manage such a thing as boarding one of those hurrying guns, even though they were invited to climb aboard. If the others tried it he, Bumpus, would have to keep going afoot, that was all.

But of course Thad had no such scheme in his mind.... Far in the rear he had sighted a caisson on which there was but a lone Frenchman. Doubtless his companion must have met with some catastrophe, one of the bursting shells having “got him” in the wild flight.

The horses drawing this caisson did not seem capable of equalling the speed displayed by the other animals. Perhaps they, too, had suffered from particles of a bursting bomb, and, being sorely wounded, they could not exert their customary strength.

The man was using a whip vigorously. Apparently he did not fancy being left in the lurch by his mates, nor could it be pleasant to have all those explosions taking place so near by.

Thad believed he saw a small chance, if only the driver displayed heart enough to stop and allow poor Bumpus to climb aboard. He meant to do all in his power to influence the man, and for that purpose commenced making motions with his hands as the other drew near.

Of course it did not require any wonderful degree of sagacity to enable the driver to understand what was wanted. Anybody would wish to get away from that region if such a thing were at all possible. And, being a Frenchman, and a gallant fellow in the bargain, what did he do but hold his frightened horses in as he reached the spot where the four boys stood in a bunch.

He also shouted something at them in French. They may not have known just what the exact meaning of the few words were, but understood his generous act. He was inviting them to get up beside him and have a ride.

Bumpus almost frantically climbed aboard amidst much grunting, which, however, could not be heard, such was the terrific din all around them. And hardly had he managed to get a seat than the driver whipped his horses into another mad gallop.

Those boys would never forget that furious race. It was impressed on their memories after a fashion that time could not efface. The straining horses, speeding through the cloud of dust raised by the other units of the field battery; the detonations of exploding shells, which still continued to drop around them as though the unseen German gunners had the range down to a fraction; the difficulty of keeping their seats on the jumping caisson—all these things conspired to form a species of excitement that kept their nerves tingling with a constant dread lest something would suddenly happen to bring about disaster.

Once only through a miracle did they escape from death. A shell dropped upon the road back of them not ten seconds after they had passed. Had they been delayed just that length of time it must have blown caisson and all aboard into atoms; for, of course, the ammunition in the chest would also have exploded.

No one tried to talk, which was somewhat strange on the part of Giraffe, who always wanted to be heard. With all that fierce jolting knocking the wind out of them, even he realized the folly of wasting any breath.

Besides, it could do no good. They were in a position where the utmost that was possible would be to grimly hold on and trust to good fortune to presently carry them out of range of the German guns. Perhaps presently, too, they might reach the advance line of the French army, where they could hope to find shelter behind the bristling defense guns.

Down along the dusty road Thad stared. He fancied that he could see what looked like a covered bridge crossing some branch of the river. Yes, now the first gun was starting to pass over it, with the others, as well as the caissons, following swiftly behind. And higher rose that billow of dust, betraying their location to the eyes of the enemy doubtless through field-glasses and by means of aerial scouts hovering aloft.

Thad saw that one gun was missing, and he discovered it alongside the road almost at the same moment. Horses lay there with the shattered carriage supporting the gun and a human leg protruding from underneath the mass told of the terrible fate that had overwhelmed the driver. The second man was not in sight, and Thad had a suspicion that he might have been picked up by one of the other teams in passing.

Bumpus, too, caught a passing glimpse of this terrible sight, and his face was lacking its customary rosy hue; still he had as much grit as the next one when it came down to a showing, and uttered no sound to indicate his dismay, only clinched his jaws together and set the muscles of his fat cheeks as if summoning all his resolution to the fore.

They were now approaching the bridge.

Once across it and there was some hope that they might find themselves in less peril. Surely there must be a limit to the range of the guns that were sending all those bombs around them, and the stream might mark this. Thad hoped so most certainly, as he mentally counted the seconds that must elapse before they could gain the bridge.

The horses did not run as they should, and Thad knew they had been injured, for there was a perceptible limp to the gait of both animals. Only that constant lashing on the part of the driver caused them to keep going; and even that must fail before a great while.

What would happen then he knew not. At the most, they would find themselves no worse off than before they were taken aboard the caisson by the obliging driver. Afoot they would have to seek some sort of shelter and try to hide until that rain of shells had ceased.

Several times they had other narrow escapes. Once Giraffe gave a perceptible start, and Thad saw him clap a hand to his shoulder. It gave the scout leader a chill, for he, of course, believed the tall chum must have received a wound that might prove more or less serious.

“Are you hit, Giraffe?” he shouted in the other’s ear, for the din made talking in ordinary tones utterly out of the question.

“Oh, I guess it didn’t amount to much,” came the reply; “but something struck me on the arm. Still, I can’t see any sign of blood.”

Thad himself took a look.

“Your coat sleeve is torn, Giraffe,” he told the other, “and I expect you’ve had a wonderfully close shave of it. You’re in great luck, let me tell you!”

Indeed, it even seemed as if the German gunners far away were concentrating all their fire upon the vicinity of that covered bridge across the stream, for the bursting shells were more numerous than ever. It would be next door to a miracle if they were allowed to run the gantlet unscathed. At any second something might happen, and Thad did not like to imagine what this was apt to be like.

It would be only natural if all of the boys realized just then that they had been overbold in trying to reach Paris from the northwest instead of going on down the coast to Boulogne and approaching from the rear, where they might only have met swarm of fugitives fleeing from the capital and no German armies closing in.