The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Scout of To-day, by Isabel Hornibrook This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: A Scout of To-day Author: Isabel Hornibrook Release Date: January 10, 2012 [EBook #38540] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SCOUT OF TO-DAY *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Paul Fernandez and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

| “WHAT IS IT? WHAT IS IT?” |

BY

ISABEL HORNIBROOK

Author of “Camp and Trail,” “Lost in Maine Woods,” “Captain Curly’s Boy,” etc., etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1913

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY ISABEL HORNIBROOK

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published June 1913

AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED TO

“NED”

The Author expresses her indebtedness to Edmund

Richard Cummins for the song, “The Scouts of

the U.S.A.”

CONTENTS

| I. | The Great Woods | 1 |

| II. | Only a Chip’ | 17 |

| III. | Raccoon Junior | 34 |

| IV. | Varney’s Paintpot | 55 |

| V. | “You Must Look Out!” | 70 |

| VI. | The Friction Fire | 82 |

| VII. | Members of the Local Council | 104 |

| VIII. | The Bowline Knot | 121 |

| IX. | Godey Peck | 145 |

| X. | The Baldfaced House | 159 |

| XI. | Estu Preta! | 178 |

| XII. | The Christmas Brigade | 196 |

| XIII. | The Big Minute | 207 |

| XIV. | A River Duel | 215 |

| XV. | The Camp on the Dunes | 230 |

| XVI. | The Pup-Seal’s Creek | 244 |

| XVII. | The Signalman | 262 |

| XVIII. | The Log Shanty Again | 271 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

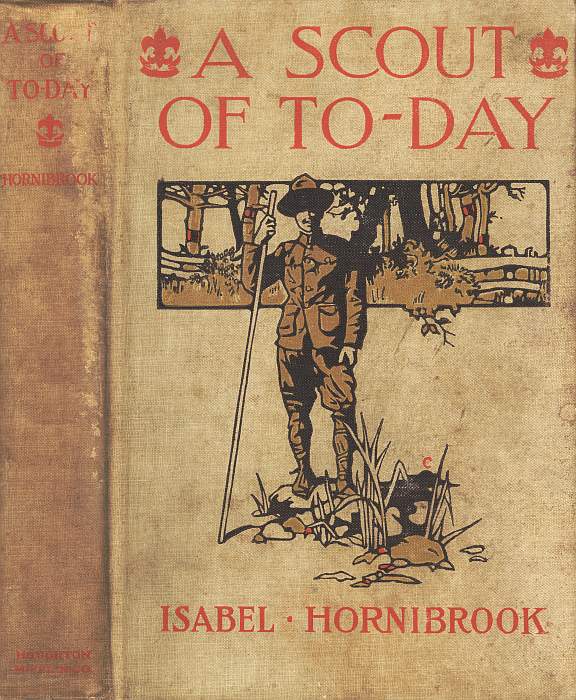

| “What is it? What is it?” (page 99) | Colored Frontispiece |

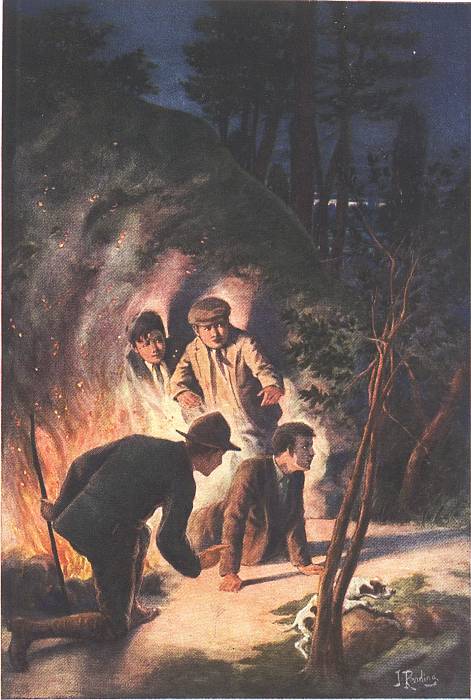

| “Help! Help!” | 56 |

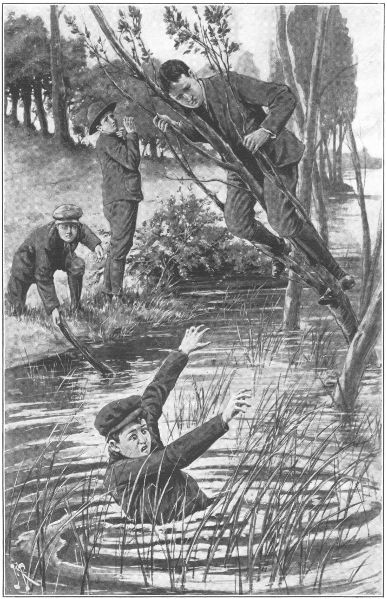

| “Mak’ you s-silent! W’at for you spik lak dat?” | 150 |

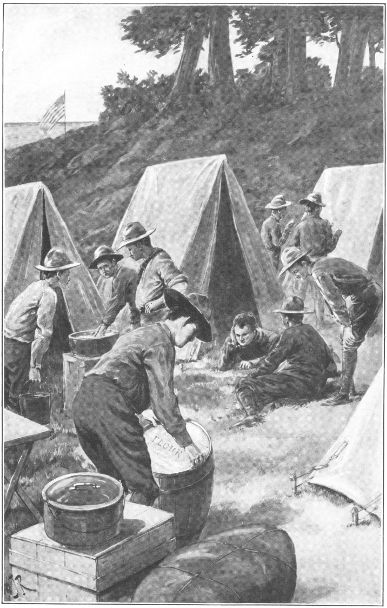

| In Camp | 238 |

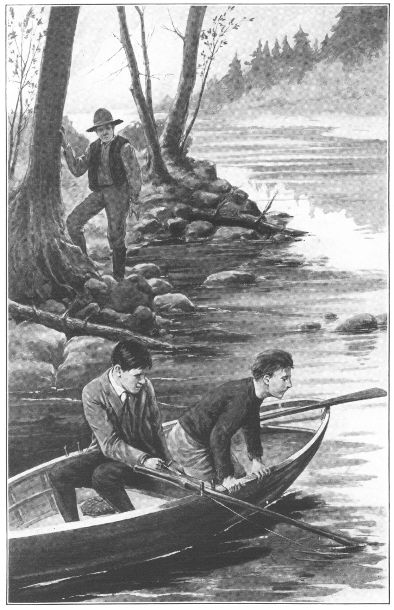

| “Can’t you see the tide is leaving you?” | 252 |

From drawings by J. Reading

A SCOUT OF TO-DAY

CHAPTER I

THE GREAT WOODS

“Well! this would be the very day for a long tramp up into the woods. Tooraloo! I feel just in the humor for that.”

Colin Estey stretched his well-developed fourteen-year-old body among the tall feathery grasses of the broad salt-marsh whereon he lay, kicking his heels in the September sunshine, and gazed longingly off toward the grand expanse of New England woodland that bordered the marshes and, rising into tree-clad hills, stretched away much farther than the eye could reach in apparently illimitable majesty.

Those woods were the most imposing and mysterious feature in Colin’s world. They bounded it in a way. Beyond a certain shallow point in them lay the Unknown, the Woodland Wonder, whereof he had heard much, but which he had never explored for himself. And this reminded him unpleasantly that he was barely fourteen, [Pg 2] in stature measuring five feet three and three eighths, facts which never obtruded themselves baldly upon his memory when he romped about the salt-marshes, or rowed a boat—or if no boat was forthcoming, paddled a washtub—on the broad tidal river that wound in and out between the marshes.

Yet though the unprobed mystery of the dense woods vexed him with the feeling of being immature and young—woodland distances look vaster at fourteen than at eighteen—it fascinated him, too, more than did any riddle of the salt-marshes or lunar enigma of the ebb and flow of tide in the silvery, brackish river formed by an arm of sea that coursed inland for many a mile to meet a freshwater stream near the town where Colin was born.

Any daring boy above the age of ten could learn pretty nearly all there was to know about that tidal river: of the mammal and fish wherewith it teemed, from the great harbor seal, once the despot of the river, to the tiny brit that frolicked in the eddies; and about the graceful bird-life that soared above its brackish current.

He could bathe, shrieking with excitement, as wild from delight as any young water-bird, in the foam of the rocky bar where fresh stream and [Pg 3] salt stream met with a great crowing of waters and laughter of spray.

He could imitate the triple whistle, the shrill “Wheu! Wheu! Wheu!” of the greater yellow-legs so cleverly as to beguile that noisy bird, which is said to warn every other feathered thing within hearing, into forgetting its panic and alighting near him.

He could give the drawn-out, plaintive “Ter-lee-ee!” call of the black-breasted plover, and find the crude nest of the spotted sandpiper nestling beneath a tall clump of candle-grass.

All these secrets and many more were within easy reach and could be studied in his unwritten Nature Primer whose pages were traced in the flight of each bird and the spawn of every fish.

But the Heart of the Woods was a closed book to most fourteen-year-old boys born and brought up in the little tidal town of Exmouth.

Colin had often longed to turn the pages of that book—to penetrate farther into the woods than he had dared to do yet. This longing was fanned by the tales of men who had hunted, trapped or felled trees in them, who could spell out each syllable of the woodlore to be studied in their golden twilight; and who, as they roved and read, could put a finger on many a colored [Pg 4] illustration of Nature’s methods set against a green background of branches or fluttering underbrush, like the flitting foliage of moving pictures.

To-day the wood-longing possessed Colin so strongly that it actually stung him all over, from his neck to his drumming, purposeless heels.

He glanced up into the brilliant September sky arching the salt-marshes, questioning it as to what might be going on in the woods at this moment under its imperial canopy.

And the blue eye of the sky winked back at him, hinting that it knew of forest secrets to be discovered to-day—of fascinating woodland creatures to be seen for a moment at their whisking gambols.

The sunlight’s energy raced through him. The briny ozone of the salt-marshes was a tickling feather in his nostrils, teasing him with a desire to find an outlet for that energy in some new and unprecedented form of activity.

He sprang to his feet, spurning the plumy grass.

“Gee whiz! I’m not going to lie here any longer, smelling marsh-hay,” he cried half articulately, his eye taking in the figures of two hay-makers who were mowing the tall marsh-grass [Pg 5] and letting it lie in fragrant swathes to dry into the salt hay that forms such juicy fodder for cattle. “It’s me for the woods to-day! I want to go farther into those old woods than I’ve ever gone before—far enough to find Varney’s Paintpot and the Bear’s Den—and the coon’s hole that Toiney Leduc saw among the alders an’ ledges near Big Swamp!”

He halted on the first footstep, whistling blithely to a gray-winged yellow-legs that skimmed above his head. The curly, boyish whistle, ascending in spirals, carried the musical challenge aloft: “I’m glad I’m alive and athirst for adventure; aren’t you?”

To which the bird’s noisy three-syllabled cry responded like three cheers!

“It’s me for the woods to-day!” Colin set off at an easy lope across the marshes. “I’m going to look up Coombsie and Starrie Chase—and Kenjo Red! Us boys won’t have much more time for fun before school reopens!” grammar capsizing in the sudden, boisterous eddy within him.

That eddy of excitement carried him like a feather up an earthy embankment that ascended from the low-lying marshes, over a fence, and out onto the drab highroad which a little farther [Pg 6] on blossomed out into houses on either side and became the quiet main street of Exmouth.

Colin turned his face westward toward the home of “Coombsie,” otherwise Mark Coombs—also shortened into “Marcoo” by nickname-loving boydom.

He had not gone far when his loping speed slackened abruptly to a contemplative trot. The trot sobered down to a crestfallen walk. The walk dwindled into a halt right in the middle of the sunny road.

“Tooraloo! here comes Coombsie now,” he ejaculated behind his twitching lips. “And some one with him! Oh, I forgot all about that!” Dismay stole over his face at the thought. “Of course it’s the strange boy, Marcoo’s cousin, who came from Philadelphia yesterday and is going to stay here for ever so long—six months or so—while his parents travel in Europe. This spoils our fun. Probably he won’t want to start off on a long hike through the woods,” rigidly scanning the approaching stranger as a stiffened terrier might size up a dog of a different breed. “His folks are rich, so Marcoo said; I suppose he’s been brought up in a city flowerpot—and isn’t much of a fellow anyhow!” with a disgruntled grin.

But as the oncoming pair drew within twenty yards of the youthful critic the latter’s tense face-muscles relaxed. Reassurance crept into his expression.

“Gee! he looks all right, this city boy. He’s not dolled-up much anyway! And he doesn’t look ‘Willified’ either!” was Colin’s complacent comment.

No, the stranger’s dress was certainly not patterned after the fashion of the boy-doll which Colin Estey had seen simpering in store-windows. He wore a khaki shirt stained with service, rough tweed knickerbockers and a soft broad-brimmed hat. He carried his coat; the ends of his blue necktie dangled outside his shirt, one was looped up into a careless knot. His gray eye was rather more than usually alert and bright, his general appearance certainly not suggestive of a flowerpot plant; his step, quick and springy, embodied the saline breeze that skipped over the salt-marshes.

So much Colin took in before criticism was blown out of his mind by a shout from Coombsie.

“Hullo! Col,” exclaimed Marcoo. “Say, this is fine! We were just starting off to hunt you up—Nix and I! This is my cousin, Nixon Warren, who popped up here from Philadelphia [Pg 8] late last night. Nix, this is my chum, Colin Estey!”

The two boys acknowledged the introduction with gruff shyness.

“Nixon and I settled on going down the river to-day in Captain Andy’s power-boat, and Mother put us up a corking good luncheon,” Marcoo significantly swung a basket pendant from his right hand. “But we’ve just been talking to Captain Andy,” glancing backward over his shoulder at the receding figure of an elderly man who limped as he walked, “and he says he can’t take us to-day. He won’t even loan us the Pill.” Coombsie gesticulated with the basket toward the broad tidal river gleaming in the sunshine, on which rode a trim gasolene launch with a little rowboat, so tubby that it was almost round and aptly named the Pill, lying as tender beside it.

“Pshaw! the Pill isn’t much of a boat. One might as well put to sea in a shoebox!” Colin chuckled.

“I know! Well, we can’t go on the river anyhow, so we’ve determined to take the basket along and spend the whole day in the woods. Nix is—”

“Great O!” whooped Colin, breaking in. [Pg 9] “That’s what I’ve been planning on doing too. I want to go far into the woods to-day,”—his hands doubled and opened excitedly, as if grasping at something hitherto out of reach,—”farther than I’ve ever been before,—far enough to see Varney’s Paintpot and the old Bear’s Den—and some of the other wonders that the men tell about!”

“But there aren’t any bears in these Massachusetts woods now?” It was the strange boy, Nixon Warren, who eagerly spoke.

“Not that we know of!” Coombsie answered. “If one should stray over the border from New Hampshire he manages to lie low. Apparently there’s nothing bigger than a deer traveling in our woods to-day—together with foxes in plenty and an occasional coon. The last bear seen in this region, Nix, had his den in the cave of a great rock in the thickest part o’ the woods. He was such an everlasting nuisance, killing calves and lambs, that a hunter tracked him into the cave and killed him with his knife. Ever since it has been called the Bear’s Den. I’ve never seen it; nor you, Col!”

“No, but Starrie Chase has! I was going to hunt him up too, and Kenjo Red: they’re a team if you want to go into the woods; they [Pg 10] know more about them than any other boy in Exmouth.”

“Kenjo has gone to Salem to-day. And Leon Chase?” Coombsie’s expression was doubtful. “I guess Leon makes a bluff of knowing the woods better than he does. He’ll scare everything away with his dog and shotgun. Captain Andy is hunting for him now,” with another backward glance to where the massive figure of the old sea-captain was melting from view. “He’s threatening to shake Starrie until his heels change places with his head for fixing the Doctor’s doorbell last night, wedging a pin into it so that it kept on ringing until the electricity gave out—and for teasing old Ma’am Baldwin again.”

“’Mom Baldwin,’ who lives in that old baldfaced house ’way over on the salt-marshes!” Colin hooted. “Pshaw! she ought to wash her clothes at the Witch Rock, where Dark Tammy was made to wash hers, over a hundred years ago. I guess Leon knows the way to Varney’s Paintpot anyhow,” he advanced clinchingly.

“What sort of queer Paintpot is that?” Nixon Warren spoke; his stranger’s part in the conversation was limited to putting excited questions.

“It’s a red-ochre swamp—a bed of moist red [Pg 11] clay—that’s hidden somewhere in the woods,” Colin explained. “The Indians used it for making paint. So did the farmers, hereabouts, until a few years ago. I believe it’s mostly dried up now.”

“Whoopee! if we could only find it, we might paint ourselves to our waists, make believe we were Indians and go yelling through the woods!” Nixon’s eye sparkled like sun-touched granite, and Colin parted with the last lingering suspicion of his being a flowerpot fellow.

This suggestion settled it. Starrie Chase, otherwise Leon, might let his boyish energy leak off as waste steam in planting another thorn in the side of the hard-worked doctor who bore the burdens of half the community, and in persecuting lonely old women, but—he was supposed to know the way to Varney’s Paintpot!

And the three started along the road to find him.

The quest did not lead them far. Rounding a bend in the highroad, they came abruptly upon Leon Starr Chase, familiarly called Starrie, almost a fifteen-year-old boy, of Nixon’s age.

He was leaning against a low fence above the marshes, holding a dead bird high above the head of a very lively fox-terrier whose tan ears [Pg 12] gesticulated like tiny signal flags as he jumped into the air to capture it, with a short one-syllabled bark.

“Ha! you can’t catch it, Blink—and you shan’t have it till you do,” teased his master, lowering its limp yellow legs a little.

The dog’s nose touched them. The next instant he had the bird in his mouth.

With equal swiftness he dropped it on the sidewalk, growling and gagging at the warm feathers which almost choked him. “Ugh-r-r!” He spurned it with his black nose along the ground, the tiny yellow claws raking up minute spirals of dust.

“There! I knew you wouldn’t eat it,” remarked his master indifferently. “You’re a spoiled pup!” Simultaneously Leon caught sight of the three boys making toward him and burst into a complacent shout of recognition.

“Hullo, Colin! Hullo, Coombsie!” he cried. “See what I’ve got! Six yellow-legs! I fired into a flock; the first I’ve seen this year. They were going from me and I dropped half a dozen of them together, with this old ‘fuzzee’!” He touched an ancient shotgun propped beside him. “I’ve shot quite a number one at a time this week. [Pg 13]”

His left hand went out to a huddle of still quivering feathers on top of the fence in which five pairs of yellow spindle-legs were tangled like slim twigs.

Colin, as was expected of him, burst into an exclamation of wonder at this destructive skill. Coombsie’s admiration was more forced.

Blink, the terrier, scornfully rolled over the feathered thing in the dust. He snapped angrily at the stranger, Nixon Warren, who tried to pick it up and examine it.

“That bird won’t be fit to eat now, after the dog has played with it,” suggested the latter, addressing Leon without the benefit of an introduction.

“I don’t care. Probably I’ll give the whole bunch of yellow-legs away, anyhow—Mother doesn’t like their sedgy flavor. She’d rather I’d let the birds alone, I guess!”

“Why do you shoot so many if you don’t want them?”

“Oh! partly for the sport and partly because these ‘Greater Yellow-legs’ are such telltales that they warn every duck and other bird within hearing by their noisy whistle.”

Impulsively Nixon put out a finger and touched one slim leg with its limp claw that protruded [Pg 14] from the fence. At the same moment he glanced upward.

Over the boys’ heads, having just risen from the feathery marshes, skimmed a feathered telltale, live counterpart of the one he touched, its legs golden spindles in the sunshine, its shrill joy-whistle: “Wheu! Wheu! Whe-eu!” proclaiming the thanksgiving which had rioted through Colin’s mind on the fragrant salt-marshes: “Glad I’m alive! Glad I’m alive! Glad—I’m alive!”

A smothered exclamation broke from Coombsie as he followed the finger and the flight.

Leon snatched up the gun.

“One can’t have too much of a good thing: I guess I could drop that ‘telltale,’ too!”

But Marcoo’s hand fastened upon his arm with an impulsive cry.

“Eh! What’s the matter with you—Flutter-budget?” Lowering the pointed shotgun, Leon whisked round; his restless brown eyes had a lightning trick of shutting and opening, as if he were taking a photograph of the person addressed, which was in general highly disconcerting to the boy who differed from him. “No need to make a fuss! I wouldn’t let her off here, anyhow,” he added, fondling the gun. “Father [Pg 15] would be fined if I should fire a shot on the highroad.”

“We’re starting off on a hike—for a long tramp into the woods, Leon,” began Coombsie hurriedly, anxious to create a diversion. “We want you to come with us, as leader; Colin says that you know the way to Varney’s Paintpot!”

The other’s expression changed like a rocket: Starrie Chase enjoyed leading other boys, even more than he reveled in “popping yellow-legs”—for the former Nature had intended him.

“All right!” he responded with swift eagerness. “Just, you fellows, keep an eye on my gun while I run home with the birds; I’ll be back in a minute!”

“Oh! you’re not going to take your gun into the woods?”

“Sure—I am! I might get a chance at a fox!”

“Won’t it be an awful nuisance carrying it all the way through the thick undergrowth—we want to go as far into the woods as the Bear’s Den?” suggested Marcoo tactfully.

“Well, perhaps it would. I’ll just scoot home then, and be back in no time!”

He snatched the dead birds from the fence, raced away and reappeared in three minutes, with the terrier barking at his heels.

“I’m going to let Blink come anyhow; he’ll have a great time chasing things—eh, Blinkie?” Leon made a hurdle of his outstretched arm for the scampering dog to jump over it.

And the terrier replied in a volley of excited barks, saying in doggy talk: “Fellows! if there’s fun ahead, I’m in with you. The woods are a grand old playground!”

He led the way, and the four boys followed, jostling each other merrily, rubbing their high spirits together and bringing sparks from the contact—bound for that mysterious forest Paintpot.

But the stranger, Nixon Warren, could not forbear throwing one backward glance from under his wide-brimmed hat at the poor dog-scorned yellow-legs, its joy-whistle silenced, stiffening in the dust.

CHAPTER II

ONLY A CHIP’

“Oh! I wish I had worn my tramping togs,” exclaimed Nixon Warren as the four boys, after covering an easy mile along the highroad and over the uplands that lay between marsh and woodland, plunged, whooping, in amid the forest shadows roofed by the meeting branches of pines, hemlocks, oaks, and birches, with here and there a maple already turning ruddy, that formed the outposts of the dense woods.

A dwarf counterpart of the same trees laced with vines and prickly brambles made an undergrowth so thick that they parted with shreds of their clothing as they went threshing through it, in a fascinating gold-misted twilight, through which the slender sunbeams flashed like fairy knitting-needles weaving a scarf of light and shade around each tall trunk.

“Why! you’re better ‘togged’ for the woods than the rest of us are,” answered Leon Starr Chase, looking askance at the new boy. “That’s a dandy hat; must shade your eyes a whole lot [Pg 18] when you’re tramping on open ground! I guess ours don’t need any shading!”

A wandering sunbeam kindled a brassy spark in Leon’s brown eye which looked as if it could face anything unabashed. In his mind lurked the same suspicion that had hovered over Colin’s at first sight of Nixon, that this newcomer from a distant city might be somewhat of a flowerpot fellow, delicately reared and coddled, not a hardy plant that could revel and rough it in the wilderness atmosphere of the thick woods.

Nothing about the boy-stranger supported such an idea for a moment, except to Leon, as the party progressed, the interest which he took in the floral life of the woodland: in objects which Starrie Chase who invariably “hit the woods” as he phrased it, with destruction in the forefront of his thoughts, generally overlooked, and therefore did not consider worth a second glance.

He stood and gaped as Nixon, with a shout of delight, pounced upon some rosy pepper-grass, stooped to pick a wood aster or gentian, or pointed out to Coombsie the green sarsaparilla plant flaunting and prolific between the trees.

“What do you call this, Marcoo?” the strange boy would exclaim delightedly, finding novel treasure trove in the rare white blossoms of [Pg 19] Labrador tea. “I don’t remember to have seen this flower on any of our hikes through the Pennsylvania woods!”

To which Coombsie would make answer:—

“Don’t ask me, Nix; I know a little about birds, but when it comes to knowing anything of flowers or plants—excepting those that are under our feet every day—I ‘fall down flunk!’ Hullo! though, here are some devil’s pitchforks —or stick-tight—I do know them!”

“So do I!” Nixon stooped over the tall bristly flower-heads, rusty green in color, and gathered a few of the two-pronged seed-vessels that cling so readily to the fur of an animal or the clothing of a boy. “It’s funny to think how they have to depend upon some passing animal to propagate the seeds. Say! but they do stick tight, don’t they?” And he slyly slipped a few of the russet pitchforks inside Leon’s collar—whereupon a whooping scuffle ensued.

“It looks to me as if some lightfooted animal were in the habit of passing here that might carry the seeds along,” said the perpetrator of the prank presently, dropping upon his hands and knees to examine breathlessly the leaves and brambles pressed down into a trail so light that it seemed the mere shadow of a pathway leading [Pg 20] off into the woods at right angles from where the boys stood.

“You’re right. It’s a fox-path!” Leon was examining the shadow-tracks too. “A fox trots along here to his hunting-ground where he catches shrews an’ mice or grasshoppers even, when he can’t get hold of a plump quail or partridge. Whew! I wish I’d brought my gun.”

Dead silence for two minutes, while each ear was intently strained to catch the sound of a sly footfall and heard nothing but the noisy shrilling of the cicada, or seventeen-year locust, with the pipe of kindred insects.

“Look! there’s been a partridge at work here,” cried Nixon by and by, when the still game was over and the boys were forging ahead again.

He pointed to a decayed log whose flaky wood, garnished here and there with a tiny buff feather, was mostly pecked away and reduced to brown powder by the busy bird which had wallowed there.

“He’s been trying to get at some insects in the wood. See how he has dusted it all up with his claws an’ feathers!” went on the excited speaker. “Oh—but I tell you what makes you feel happy!” He drew a long breath, turning suddenly, impulsively, to the boys behind him. [Pg 21] “It’s when you’re out on a hike an’ a partridge rises right in front of you—and you hear his wings sing!”

Colin and Coombsie stared. The strange boy’s look flashed with such frank gladness, doubled and trebled by sharing sympathetically, in so far as he could, each bounding thrill that animated the wild, free life about him! They had often been moved by the liquid notes from a songster’s throat, but had not come enough into loving touch with Nature to hear music in a bird’s wings.

If Leon had heard it, his one idea would have been to silence it with a shot. He stood still in his tracks, bristling like his dog.

“Ughr-r! ‘Singing wings’!” he sneered. “Aw! take that talk home to Mamma.”

“Say that once again, and I’ll lick you!” The stranger’s gaze became, now, very straight and inviting from under his broad-brimmed hat.

The atmosphere felt highly charged—unpleasantly so for the other two boys. But at that critical moment an extraordinary sound of other singing—human singing—was borne to them in faint merriment upon the woodland breeze, so primitive, so unlike anything modern, that it might have been Robin Hood himself or one of his green-coated Merry Men singing a roundelay [Pg 22] in the woods to the accompaniment of a woodchopper’s axe.

“What is it? Who is—it?” Nixon’s stiffening fists unclosed. His eye was bright with bewilderment.

“Houp-la! it’s Toiney—Toiney Leduc.” Colin broke into an exultant whoop. “Now we’ll have fun! Toiney is a funny one, for sure!”

“He’s more fun than a circus,” corroborated Coombsie. “We’re coming to a little farm-clearing in the woods now, Nix,” he explained, falling in by his cousin’s side as the four boys moved hastily ahead, challenges forgotten. “There’s a house on it, the last for miles. It’s owned by a man called Greer, and Toiney Leduc works for him during the summer an’ fall. Toiney is a French-Canadian who came here about a year ago; his brother is employed in one of the shipbuilding yards on the river.”

The merry, oft-repeated strain came to them more distinctly now, rolling among the trees:—

“He’s singing about the woman who was taking care of her sheep and how the lamb got his chin in the milk! He translated it for me,” said Colin.

“’Translate!’ He doesn’t know enough English to say ‘Boo!’ straight,” threw back Leon, as he gained the edge of the clearing. “It is Toiney!” he cried exultingly. “Toiney—and the Hare!”

“The—what? My word! there are surprises enough in these woods—what with forest paintpots—and the rest.” Nixon, as he spoke, was bounding out into the open too, thrilled by expectation: a musical woodchopper attended by a tame rodent would certainly be a unique item upon the forest playbill which promised a variety of attractions already.

But he saw no skipping hare upon the green patch of clearing—nothing but a boy of twelve whose full forehead and pointed face was very slightly rodent-like in shape, but whose eyes, which at this startled moment showed little save their whites, were as shy and frightened as a rabbit’s, while he shrank close to Toiney’s side.

“My brother says that whenever he sees that boy he feels like offering him a bunch of clover or a lettuce leaf!” laughed Leon, repeating the [Pg 24] thoughtless speech of an adult. He stooped suddenly, picked some of the shaded clover leaves and a pink blossom: “Eh! want some clover, ‘Hare’?” he asked teasingly, thrusting the green stuff close to the face of the abnormally frightened boy.

The hapless, human Hare sought to efface himself behind Toiney’s back. And the woodchopper began to execute an excited war-dance, flourishing the axe wherewith he had been musically felling a young birch tree for fuel.

“Ha! you Leon, you coquin, gamin—rogue —you’ll say dat one time more, den I go lick you, me!” he cried in his imperfect English eked out with indignant French.

“No, you won’t go lick me—you!” Nevertheless Starrie Chase and his mocking face retreated a little; he had no fancy for tackling Toiney and the axe.

“That boy’s name is Harold Greer; it’s too bad about him,” Coombsie was whispering in Nix Warren’s ear. “The doctor says he’s ‘all there,’ nothing wrong with him mentally. But he was born frightened—abnormally timid—and he seems to get worse instead o’ better. He’s afraid of everything, of his own shadow, I think, and more still of the shadows of others: I mean [Pg 25] he’s so shy that he won’t speak to anybody—if he can help it—except his grandfather and Toiney and the old woman who keeps house for them.”

Nixon looked pityingly at the boy who lived thus in his own shadow—the shadow of a baseless fear.

“Whew! it must be bad to be born scared!” he gasped. “I wish we could get Toiney to sing some more.”

At this moment there came a wild shout from Colin who had been exploring the clearing and stumbled upon something near the outhouses.

“Gracious! what is it—a wildcat?” he cried. “It isn’t a fox—though it has a bushy tail! It’s as big as half a dozen squirrels. Hulloo-oo!” in yelling excitement, “it must be a coon—a young coon.”

There was a general stampede for the hen-house, amid the squawking cackle of its rightful inhabitants.

Toiney followed, so did the human Hare, keeping always behind his back and casting nervous glances in Leon’s direction.

“Ha! le petit raton—de littal coon!” gasped the woodchopper. “W’en I go on top of hen-house dis morning w’at you t’ink I fin’ dere, engh? I fin’ heem littal coon! I’ll t’ink he kill [Pg 26] two, t’ree poulets—littal chick!” gesticulating fiercely at the dead marauder and at the bodies of some slain chickens. “Dog he kill heem; but, sapré! he fight lak diable! Engh?”

The last exclamation was a grunt of inquiry as to whether the boys understood how that young raccoon, about two-thirds grown, had fought. Toiney shruggingly rubbed his hands on his blue shirt-sleeves while he pointed to a mongrel dog, the other participant in that early-morning battle, with whom Leon’s terrier had been exchanging canine courtesies.

Blink forsook his scarred brother now and sniffed eagerly at the coon’s dead body as he had sniffed at the poor yellow-legs in the dust.

“Where did he come from, Toiney? Do you suppose he strayed from the coon’s hole that you found in the woods, among some ledges near Big Swamp?” Colin, together with the other boys, was stooping down to examine the dead body of the wild animal which measured nearly a foot and a half from the tip of its sharp nose to the beginning of the bushy tail that was handsomely ringed with black and a shading buff-color.

“Yaas, he’ll com’ out f’om de forêt—f’om among heem beeg tree.” Toiney Leduc, letting [Pg 27] his axe fall to the ground, waved an eloquent right arm in its flannel shirt-sleeve toward the woods beyond the clearing.

“Isn’t his fur long and thick—more like coarse gray hair than fur?” Nixon stroked the raccoon’s shaggy coat.

“Tell us how to find those ledges where the hole is? There may be some live ones in it. I’d give anything to see a live coon,” urged Coombsie.

“Ah! la! la! You no fin’ dat ledge en dat swamp. Eet’s littal black in dere, in gran’ forêt—in dem big ole hood,” came the dissuading answer.

“He always says ‘hood’ for ‘wood,’” explained Marcoo sotto voce.

“Ciel! w’en you go for fin’ dat hole, dat’s de time you get los’—engh?” urged Toiney, suddenly very earnest. “You walkee, walkee—lak wit’ eye shut—den you haf so tire’ en so lonesam’ you go—deaded.”

He flung out his hands with an eloquent gesture of blind despair upon the last word, which shot a warning thrill to the boys’ hearts. Three of them looked rather apprehensively toward the dense woods that stretched away interminably beyond the clearing.

But the fourth, Leon, was not to be intimidated by anything short of Toiney brandishing the woodchopper’s axe.

He paused in his gesture of slyly offering more clover to the boy with the frightened eyes.

“Oh! I know the woods pretty well, Toiney,” he said. “I’ve been far into them with my father. I can find the way to Big Swamp.”

“I’ll bet me you’ head you get los’—hein?”

“Why don’t you bet your own seal-head, Toiney? You can’t say ‘Boo!’ straight.” Leon scathingly pointed to the Canadian’s bare, closely cropped head, dark and shiny as sealskin.

“Sapré! I’ll no bet yous head—you Leon—for nobodee want heem, axcep’ for play ping-pong,” screamed the enraged Toiney.

There was a general mirthful roar. Leon reddened.

“Oh, come; let’s ‘beat it’!” he cried. “We’ll never find that coon’s burrow, or anything else, if we stand here chattering with a Canuck. Look at Blink! He’s after something on the edge of the woods. A red squirrel, I think!”

He set off in the wake of the terrier, and his companions followed, disregarding further protests in Toiney’s ragged English.

Once more they were immersed in the woods [Pg 29] beyond the clearing. The terrier was barking furiously up a pine tree, on whose lowest branch sat the squirrel getting off an angry patter of “Quek-Quik! Quek-quek-quek-quik!” punctuated with shrill little cries.

“Hear him chittering an’ chattering! There’s some fire to that conversation. See! the squirrel looks all red mouth,” laughed Nixon.

The mouth of the little tree-climbing fury yawned, indeed, like a tiny coral cave decorated with minute ivories as he sat bolt upright on the dry branch, scolding the dog.

“Oh! come on, Blink, you can’t get at him. You can chase a woodchuck or something else that isn’t quite so quick, and kill it!” cried his master.

The “something else” was presently started in the form of a little chipmunk, ground brother to the squirrel, which had been holding solitary revel with a sunbeam on a rock.

With a frightened flick of its gold-brown tail it sought shelter in a cleft of a low, natural wall where some large stones were piled one upon another.

Instantly it discovered that this shallow refuge offered no sure shelter from the dog following hot upon its trail. Forth it popped again, with a [Pg 30] plaintive, chirping “Chip! Chip! Chir-r-r!” of extreme terror and fled, like a tuft of fur wafted by the breeze, to its real fortress, the deep, narrow hole which it had tunneled in under a rock, and which it was so shy of revealing to strangers that it would never have sought shelter there save in dire extremity.

It was such a very small hole as regards the round entrance through which the chipmunk had squeezed, which did not measure three inches in circumference—and such a touchingly neat little hole, for there was no trace of the earth which the little creature had scattered in burrowing it—that it might well have moved any heart to pity.

The terrier finding himself baffled, sat down before it, and pointed his ears at his master, inquiring about the prospects of a successful siege.

“He was too quick for you that time, Blinkie. But you’ll get another chance at him, pup,” guaranteed Leon, while his companions were endeavoring to solve the riddle—one of the minor charming mysteries of the woods—namely, what the ground-squirrel does with the earth which he scatters in tunneling his grass-fringed hole.

No such marvel appealed to Leon Chase! [Pg 31] With lightning rapidity he was wrenching a thin, rodlike stick from a near-by white birch, and tearing the leaves off. Before one of the other boys could stop him, he had inserted this as a long probe in the hole, working the cruel goad ruthlessly from side to side, scattering earth enough now and torn grass on either side of the spic-and-span entrance.

“Ha! you haven’t seen the last of him, Blink!” he cried. “I’ll soon ‘podge’ him out of that! This hole runs in under a rock; so there can’t be a sharp turn in it, as is the case with the chip-squirrel’s hole generally! I guess I can reach him with the stick; then he’ll be so frightened that he’ll pop out right in your face,” forming a quick deduction that did credit to his powers of observation and made it seem a bruising pity as well for persecutor as persecuted that such boyish ingenuity should be turned to miserable ends.

Leon’s eyes were beady with malicious triumph. His breath came in short excited puffs. So did the terrier’s. It boded ill for the tormented chipmunk cowering at the farthest end of the desecrated hole.

“Hullo! that’s two against one and it isn’t fair play. Quit it!” suddenly burst forth a ringing boyish voice. “The chip’ was faster than the [Pg 32] dog—he ought to have an even chance for his life, anyhow!”

Leon, crouching by the hole, looked up in petrified amazement. It was Nixon Warren, the stranger to these woods, who spoke. The tormentor broke into an insulting laugh.

“Eh—what’s the matter with you, Chicken-heart?” he sneered. “None o’ your business whether it’s fair or not!”

A flash leaped from the gray eyes under Nixon’s broad hat that defied the sneer applied to him. His chest heaved under the Khaki shirt with whose metal buttons a sunbeam played winsomely, while with defiant vehemence Leon worked his probing stick deeper, deeper into the hole where the mite of a chipmunk shrank before the cruel goad that would ultimately force it forth to meet the whirlwind of the dog’s attack.

Colin and Coombsie held their breath, feeling as if they could see the trembling “chipping” fugitive pressed against the farthest wall of its enlarged retreat.

Another minute, and out it must pop to death.

But upon the dragging, prodding seconds of that minute broke again the voice of the chipmunk’s champion—hot and ringing.

“Quit that!” it exploded. “Stop wiggling the stick in the hole—or I’ll make you!”

“You’ll make me, eh? Oh! run along home to Mamma—that’s where your place is!” But right upon the heels of the sneer a sharp question rushed from Leon’s lips: “Who are you—anyhow —to tell me to stop?”

And the tall trees bowed their noble heads, the grasses ceased their whispering, even the seventeen-year locust, shrilling in the distance, seemed to suspend its piping note to listen to the answer that rushed bravely forth:—

“I’m a Boy Scout! A Boy Scout of America! I’ve promised to do a good turn to somebody—or something—every day. I’m going to do it to that chipmunk! Stop working that stick in the hole!”

“Gee whiz! I thought there was something queer about you from the first.”

The mouth of Starrie Chase yawned until it rivaled the enlarged hole. Sitting on his heels, his cruel probing momentarily suspended, he gazed up, as at a newfangled sort of animal, at this daring Boy Scout of America—this Scout of the U.S.A.

CHAPTER III

RACCOON JUNIOR

“Scout or no scout, you are not going to boss me!”

Thus Starrie Chase broke the breathless silence that reigned for half a minute in the woods, following upon Nixon’s declaration that he was a boy scout, bound by the scout law to protect the weak among human beings and animals.

For the space of that half-minute the tormenting stick had ceased to probe the hole. The wretched chipmunk, cowering in the farthest corner of its once neat retreat, had a respite.

But Leon—who was not inherently cruel so much as thoughtlessly teasing and the victim of a destructive habit of mind, now felt that should he yield a point to this fifteen-year-old lad from a distant city, the leadership which he so prized, among the boys of Exmouth, would be endangered. He was the recognized head of a certain youthful male gang, of which Colin and Coombsie—though the latter occasionally deplored his methods—were leading representatives.

“Go ahead, scout, prevent my doing anything I want to do—if you can!” he flung out, his brown eyes winking upward with that snapshot quickness as if he were photographing on their retina the figure of that new species of animal, the scout of the U.S.A. “I’ve heard of your kind before; you know a lot of things that nobody else knows—or wants to know either!”

The last words were to the accompaniment of the goading stick which began to move vehemently to and fro in the hole again. That neat little hole, which had been one of the humbler miracles of the woods, now gaped as an ugly, torn fissure beneath its roof of rock.

Before it was a defacing débris of torn grass and earth in which Blink scratched impatiently, whining over the delay in the chip-squirrel’s exit.

“Oh! give it up, Leon; I believe I can hear him stirring in the hole!” pleaded Colin Estey.

Simultaneously the scout flung himself on his knees before the chipmunk’s fortress, well-nigh captured, and seized the cruel goad.

“Let go of this stick or I’ll lick you with it! I can; I’m as old—older than you are!” Leon was now a red-eyed savage.

“That would be like your notion of fair play! [Pg 36] Oh! drop the stick an’ come on with your fists! I’m not afraid of you.”

The probable result of such a duel remains a problem; any slight advantage in age was on Leon’s side, but each alert movement of the boy scout showed that he possessed eye, mind, and muscle trained to the fullest to cope with any situation that might arise. Whoever might prove victor, the expedition to Varney’s Paintpot would have been abruptly frustrated by a fight among the exploring party, had not Marcoo the tactful interfered.

“Oh! what’s the use of fighting about a chip’?” he cried, thrusting a plump shoulder between the bristling combatants. “It’s just this way, Leon: Nix is right; it’s a mean business, trying to force that chipmunk out of its hole for the dog to catch it! You can withdraw the stick right now, come with us an’ share our luncheon; or you can go off on your own hook—and you don’t get a crumb out of the basket—we’ll find the Paintpot without you!”

Leon drew a long wavering breath, looking at Colin for support.

But Public Opinion as represented by the two younger boys, was by this time entirely with the scout. For it is the genius among boys, as among [Pg 37] grown-ups, who voices what lies hidden and unexpressed, in the hearts of others; we are always moved by the bold utterance of that which we have surreptitiously felt ourselves.

Both Colin Estey and Marcoo had known what it was to feel their sense of pity and justice outraged by Leon’s persecuting methods. But it needed the trained boldness of the boy scout to put the sentiment into words; to be ready to fight for his knightly principles and win. For he had won.

Leon Chase fairly writhed at the choice set before him—at the necessity of yielding a point to the stranger! But he felt that it would be still more obnoxious to his feelings to be deserted by his companions, left to beat a solitary retreat homeward with his dog or wander—alone and fasting—through the woods, a boy hermit!

“All right! Have your way! Come along,” he cried crossly. “We’ll never get anywhere—that’s sure—if we waste any more time on a chipmunk!”

Withdrawing the stick from the enlarged aperture, he flung it away and scrambled to his feet, whistling to the dog.

It needed much moral suasion on the part of all four boys to lure the terrier away from the [Pg 38] raided hole with whose earth his slim white legs were coated. But he presently consented to explore the woods further in search of diversion.

And the incident ended without any torn fur flying its flag of pain on the summer air.

The flag of feud between the two boys, Starrie Chase and Nixon, was not, however, immediately lowered. Coombsie—a studious, thoughtful lad—had the unhappy feeling of having brought two strange fires together which might at any moment result in an explosion that would be especially disastrous on this the first day of his cousin’s visit to him.

But as one lad has remarked: “Two boys cannot remain mad with each other long: there’s always too much doing!”

And everybody knows that sawdust smothers smouldering fire! It did in this instance. After about ten minutes of “grouchy” but uneventful tramping, the forest explorers came to a logging camp, a rude shanty, flanked by a yellow mountain of sawdust where a portable sawmill had been set up during the preceding winter and taken down in spring.

In spite of the fact that so much lay before them to be seen in the woods—if haply they [Pg 39] might arrive at the various points of heart’s desire—it was not in boy-nature to refrain from scaling that unstable, shelving sawdust peak for a better view onward into those shadowy woods. And a lusty sham battle ensued, in the midst of which Leon found occasion to repay the trick played on him with the pitchfork seeds by slipping a handful of sawdust inside the scout’s khaki collar.

“Whew! that’s worse than the devil’s pitchforks,” groaned the latter, writhing and squirming in his tan shirt.

But does not a trifling discomfort under such circumstances enhance while curbing the enjoyment of a boy, tying him to earth, when his young spirit like an aeroplane, winged with sheer joy of life and youthful daring, feels as if it could spurn that earth sphere as too limited, and, riding on the breeze of heaven, seek adventure among the clouds?

In such a mood the four boys, drinking in the odor of the pine-trees as a fillip to delight, were presently exploring the loggers’ shanty, with its rude bunks, oilcloth-covered table, here an old magazine, there a worn-out stocking, relics of human habitation.

“Nobody occupies this camp during the summer, [Pg 40]” said Leon. “I think Toiney Leduc and another man worked up here last winter.”

“I’m pretty sure that Toiney did! Look there!” The scout was unfolding a piece of charred paper pinioned in a corner by a tomato can; it was a printed fragment of a French-Canadian voyageur song, at sight of which the boys made the shanty ring with:—

“But I’m not so sure that nobody is using the shanty now,” remarked Nixon presently. “See that tobacco ash and the stains on the white oilcloth!” pointing to the dingy table. “Both look fresh; the ash couldn’t possibly have remained here since last winter; ’twould have been blown away long ago by the wind sweeping through the open shanty. There’s some more of it on the mattress in this bunk,” drawing himself up to look over the side of the rude crib built into the wall. “I guess somebody does occupy the camp now—at night anyway!”

“Oh! so you set up to be a sort of Sherlock Holmes, do you?” jeered Leon.

“I don’t set up to be anything! But I can tell that the men ground their axes right here.” The scout was now kicking over a small wooden [Pg 41] trough that had reposed, bottom uppermost, amid the long grass before the shanty.

“How can you make that out?” It was Colin who spoke.

“Because, look! there’s rust on the inside of the trough, showing that there are steely particles mixed with the dust of the interior and that water has dripped into it from the revolving grindstone.”

“Pshaw! anybody could find that out who set to work to think about it,” came in a chorus from his three companions.

But that “thinking” was just the point: the others would have passed by that topsy-turvy wooden vessel, which might have been used for sundry purposes, with its dusty interior exactly the hue of the yellow sawdust, without stopping to reason out the story of the patient axe-grinding which had gone on there during winter’s bitter days.

“But, I say, what good does it do you to find out things like that?” questioned Starrie Chase, kicking over the trough, his shrewd young face a star of speculation. “If one should go about poking his nose into everything that had happened, why! he’d find stories in most things, I guess! The woods would be full of them. [Pg 42]”

“So they are!” replied the scout quickly. “That’s just what we’re taught: that every bird and animal, as well as everything which is done by men, leaves its ‘sign!’ We must try to read that ‘sign’ and store up in our minds what we learn, as a squirrel stores his nuts for winter, so that often we may find out things of importance to ourselves or others. And I’ll tell you it makes life a jolly lot more interesting than when one goes about ‘lak wit’ eye shut’! as Toiney says. I’ve never had such good times as since I’ve been a scout:—

The speaker exploded suddenly in a burst of song, throwing his broad hat into the air with a yell on the refrain that woke the echoes of the log shanty, while the breezy orchestra in the tree-tops, like noisy reed instruments, came in on the last line:—

Colin and Coombsie were enthusiastically shouting it too.

“Say! Col, that fellow suits me all right,” whispered Marcoo, nudging his chum and pointing toward the excited scout.

“Me, too!” returned Colin.

“Pshaw! he thinks he’s It, but I think the opposite,” murmured Leon truculently.

“To what troop or patrol do you belong, Nix?” questioned his cousin.

“Peewit Patrol, troop six, of Philadelphia! I was a tenderfoot for six months; now I’m a second-degree scout—with hope of becoming a first-class one soon. Want to see my badge?” pointing to his coat. “Each patrol is named after a bird or animal. We use the peewit’s whistle for signaling to each other: Tewitt! Tewitt!”

Again the woods rang with a fairly good imitation of the peewit’s—or European lapwing’s—whistling note.

“Oh! I’d put a patent on that whistle if I were you,” snapped Leon sarcastically: “I’m sure nothing like it was ever heard in these—or any other—woods! We’d better be moving on or the mosquitoes will eat us up,” he added hastily. “There hasn’t been any frost to get rid of them yet.”

But as the quartette of boys left the log-camp behind and, with the terrier in erratic attendance, [Pg 44] plunged again into the thick woods, it by and by became apparent to each that, so far as a knowledge of their exact whereabouts went or an ability to locate any point of destination, they were approaching the truth of Toiney’s words and wandering “lak wit’ eye shut!”

For a time they kept to a logging-road that branched off from the shanty, a mere grass-grown, root-obstructed pathway, over which, when that great white leveler, Winter, evened things up with his mantle of snow, the felled trees were drawn on a rough sled to some point where stood the movable sawmill.

The dense woods were intersected at long intervals by such half-obliterated paths; in their remote recesses lurked other rough shanties where a scout might read the “sign” that told of the hard life of the lumbermen.

But neither vine-laced road nor shanty was easy of discovery for the uninitiated.

“Whew! it kind o’ brings the gooseflesh to be so far in the woods as this without having the least idea whether we’re getting anywhere or not.” Thus spoke Coombsie at the end of half an hour’s steady tramping and plowing through the underbrush. “Are you sure that you know in which direction lies the cave called the Bear’s [Pg 45] Den, Leon? A logging-road runs past that, so I’ve heard.”

“Oh, we’ll arrive there in time, I guess; Varney’s Paintpot is somewhere in the same direction as the cave,” replied the pseudo-leader evasively. “They’re some distance apart, but we’ve made a bee-line from one to the other when I’ve been in the woods with my father or brother Jim.”

But these woods were a different proposition now, without an older head and more experienced woodlore to rely upon: Leon, who had never before posed as a guide through their mazes, secretly acknowledged this.

He had not imagined that it would be so difficult to find one’s way, unaided, in this wilderness of endless trees and underbrush, through whose changing aspects ran the same mystifying thread as if the gold-brown gloom of a shadowy hill-slope,—where only the sunbeams waltzing on dry pine-needles seemed alive,—or the jeweled twilight of a grassy alley bound a gossamer handkerchief about one’s eyes, so that one groped blindfold against a blank wall of uncertainty.

“Say! but I wish I had brought my pocket compass with me,” groaned the scout. “Guess I didn’t live up to our scout motto: Be Prepared! [Pg 46] But then—” he looked at his cousin—”we started out with the intention of going down the river and you objected to my trotting back for it, Marcoo, when we determined on a hike through the woods.”

“I was afraid that if the men knew what we were planning, they’d have headed us off as Toiney tried to do,” confessed Marcoo candidly.

“Well, I wish now that I had gone back; I could have packed the luncheon into my knapsack; it would have been much more easily carried than in this basket. I miss my staff too!” Nixon deposited the lunch-basket, with which he was now impeded, on the ground in a green woodland glade where the noble forest trees, red oak, cedar, maple, interspersed with an occasional pine, hemlock, or balsam fir, rose to a height of from sixty to a hundred feet, bordering a patch of open ground, starred with wildflowers, dotted with berries.

Delicate queen’s lace, purple gentians, starry wood-asters, waxen Indian pipes, made it seem as if this must be the wood-fairies’ dancing-ground, where at night they rode a moonbeam from flower to flower, and sipped juice from the milk-berries, bunch-berries or scarlet fox-berries that strayed at intervals along the ground.

“I’d like to stay here forever.” Colin stretched himself upon a bank of moss, his mind going back to the explorer’s longing, to the wood-hunger which had consumed him, as he lay upon the fragrant marsh-grass some hours before. He was getting his wish now—and not everybody gets that without having to pay for it. “The trees look kind o’ fatherly an’ protecting; don’t they?” he murmured lazily.

Yes, here one felt admitted to the companionship of those noble trees,—the greatest story-tellers that ever were, when one listens and interprets their conversations with the breeze. A “Hurrah for the woods!” was on every tongue as the boys chewed a berry or smoked a pearly orchid pipe.

Moods changed a little as they took up their wandering again and presently waded, single file, through a jungle of bushes, scrub oak, dwarf pine, pigmy cedar and birch, laced with brambles. Here the trees overhead were of less magnitude and the tall leafy undergrowth foamed about their ears, giving them somewhat the distracted feeling of being cast away on a trackless sea—each sequestered in his own little boat—with emerald billows shutting out all view of port.

“Three cheers! We’re almost through with this jungle. I guess we’re coming to more open ground again—none too soon, either!” cried Leon who led, with his dog. “Shouldn’t wonder if we were approaching a swamp: it may be Big Swamp, as the men call that great alder-swamp that’s all spongy in parts and dotted with deep bog-holes, where one might sink out of sight quick!

“For goodness’ sake! look at the crows,” he whooped three minutes later, as, leaving the wavy undergrowth behind, he plunged out on a mossy slope strewn with an occasional boulder. “The crows! What do you suppose they’re after? They’re teasing something! ‘Hollering’ at something!”

The same amazed exclamation broke from his companions’ lips. Halfway down the slope was an old and leafy chestnut tree. Around this the crows were circling, now alighting on the branches, now fluttering off again on sloping sable wing, their yellow beaks gleaming.

A cawing din filled the air, with an occasional loud “Quock!” of alarm or indignation.

“They’re teasing something—perhaps it’s a squirrel! I’ve seen them do that before; they’re regular pests!” exclaimed Leon, inconsistently [Pg 49] finding fault with the crows for being birds of the same feather with himself.

“Whew! there’s something doing here. Let’s see what it is!” Nixon was equally excited.

With the terrier scampering ahead, the four boys set off at a run toward the crow-infested tree.

“I believe there’s something—some animal—hidden in the hollow between the branches!” Leon gave vent to a low shout, his brown eyes yellow with excitement. “It’s round that the crows are hovering!”

“There is! There is! I see the end of a big, bushy tail. It isn’t a squirrel’s tail either!” returned the scout in a fever of mystification. “Let’s go softly, so that we won’t frighten the thing whatever it is—then we can have a good look at it!”

“Suppose it should be a wildcat, then we’d ‘scat’!” gasped Colin, feeling his wildest hopes and tremors fulfilled. “I see its nose—a black nose—over the edge of the hollow! It’s like—Gee! it can’t be another coon from the swamp—like the dead one that Toiney found in the hencoop?”

Simultaneously the terrier, Blink, was launching himself like a white arrow toward the spreading [Pg 50] nut-tree, which stood upon a grassy knoll, while the woods rang with his fusillade of barking.

And from the hollow in the tree came a shrill whimpering cry, remarkably like that of a small and frightened child.

Starrie Chase fairly gambolled with excitement: “That’s where you’re right, Col,” he panted. “If it isn’t a coon—another young coon—I’m a Dutchman! I hunted one in the woods, by night, with my brother, last year!”

“He keeps on singing,” breathed Coombsie. “Isn’t his cry like a two-year-old child’s?”

“Oh! if we only had my brother’s coon dog here—and could get him down from the tree—the dog might finish him!” Leon seemed emitting sparks of excitement from his pointed elbows and other quivering joints. “Go for him, Blink!” he raved, hardly knowing what he said. “You’re not afraid of anything—you feel like a mastiff! Oh! we must get him out of that tree-hollow on to the ground.”

“Caw! Caw!... Caw!... Quock! Quock!” At the approach of the boys and dog the crows set up a wilder din, describing broader circles round the tree or fluttering upward to its loftier branches.

Again came that petulant whimpering cry from [Pg 51] the hollow of the chestnut, where a young raccoon (probably brother to the intruder which had made a short bee-line through the woods, guided by instinct and its nose, to Toiney’s hencoop) now wailed and quailed, finding himself between two sets of enemies: the barking dog and excited boys below, the pestering crows above.

Abandoning the wise nocturnal habits of his forefathers, with the rashness of youth, he too had strayed at sunrise from that secluded hole among the ledges on the borders of Big Swamp, filled with dreams of juicy cornfields and other delicacies.

Not readily finding such a land of milk and honey, he climbed into the hollow of this chestnut tree, flanked by a young ash upon the knoll, and there composed himself to sleep.

But thither the crows, flocking, found him; and recognizing in him an hereditary enemy of their eggs and nestlings, set to work to make his life a burden.

Nevertheless Raccoon Junior preferred their society to that of the boys and dog which instinct warned him to dread above all other foes.

As the well-bred terrier—game enough to face any foe, though it might prove a sorry day for him if he should tackle that young raccoon—reared [Pg 52] on his hind legs, and clawed the bark of the trunk in his excitement, the rash Junior climbed swiftly out of the hollow and fled up among the branches of the tall chestnut tree, seeking to hide himself among the long thick leaves amid a stormy “Quock!” and “Caw! Caw! Caw!” from the crows.

“Oh! there—there he goes! See his stout body and funny little legs!”

“And his long gray hair and the black patch over his eyes—makes him look as if he wore spectacles!”

“And his bushy tail! Huh! there’s some class to that tail—all ringed with buff and black.”

Such cries broke from three wildly excited throats. Leon spent no breath in admiration. Like lightning, he had snatched up a stone and sent it flying up the tree after the fugitive with such good aim that it struck one of the short, climbing legs.

Another whimpering cry—sharp and shrill as that of a wounded child—rang down among the thick leaves.

“What did you do that for? You’ve broken one of his legs, I think!” exclaimed the scout.

“So much the better! If he should light down from the tree, he can’t run so fast! I want that [Pg 53] dandy tail of his—and his skin!” Starrie Chase was now beside himself with the greedy feeling, that possessed him whenever he saw a wild animal, that its own skin did not belong to it, but to him.

“Say, fellows!” he cried wildly, “if you’ll stay right here by the tree and prevent his coming down, I—I’ll run all the way back to that farm-clearing—I guess I can find my way—and bring back Toiney’s gun, and shoot him. Say—will you?”

No such promise was forthcoming.

“Well, I know what I’ll do!” Leon tore off his jacket. “I’ll tie the sleeves of my coat round the trunk of the tree; that will prevent his coming down, so I’ve heard my father say. Bother! they won’t meet. I’ll have to use your coat too, Nix!”

He snatched up the scout’s Norfolk jacket, thrown down beside the basket at the foot of the tree, and was knotting it to his own, when there was a wild shriek from Colin:—

“Look! Look! He’s jumped over into the other tree. Oh! he’s come down; he’s on the ground now—there beyond the ash tree—rolling over like a ball! Oh, he’s going—going like a slate sliding downhill!”

While Leon had been so cleverly knotting the [Pg 54] coats round the tree-trunk, and his terrier barking up it, the young coon had outwitted them and dropped like an acrobat to the ground, having gained the odds of a dozen yards in his race for safety.

Off went the terrier after him, now! Off went the four boys, hot on the trail too, madly rushing down the hill clear to the edge of the alder-swamp toward which it sloped—yes! and into its quagmire borders too, while the crows, raving like a foghorn, supplied music for the chase.

But the speed of the limping wild animal enabled it, having gained its short legs—despite the injury of the stone—to reach the shelter of a quivering clump of alders where Blink worried in and out in vain, nose to the ground—sniffing and baffled.

“Oh, we’ve lost sight of him now! He’s given us the slip,” cried Colin, recklessly dashing for the alders.

Suddenly the air cracked with his cry that raved with terror like the crows: “Help! Help! I’m into it now—into it plunk—into Big Swamp! I’m sinking—s-sinking above my waist! Help! Help!”

CHAPTER IV

VARNEY’S PAINTPOT

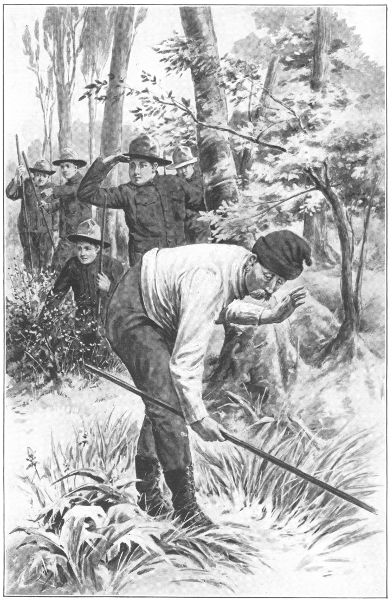

“I’m ‘plunk’ into it! I’m sinking in the swamp mud! I can’t—can’t get out! Oh—h-help—help!”

Colin’s wild cries as he found himself sinking in the oozing, olive-green mud of the vast alder-swamp, struck his comrades with a momentary blind horror.

The half-immersed boy was indeed “plunk” into it; he was submerged to his waist and slowly sinking inch by inch farther, now fairly gibbering in his frantic terror of being swallowed bodily by one of the many sucking throats of Big Swamp.

He writhed and struggled madly, snatching at the rank grass whose slimy roots came away in his hand—at the bushes—even at the brilliant poison sumac, already ruddy as a swamp lamp—with the clutch of a drowning man; Leon’s remembered words stinging his ears like noisome insects: “There are live spots in that swamp where one might go out of sight—quick! [Pg 56]”

The hideous slimy life of the spongy bog, half water, half mud!

Leon’s sharp-featured face at that moment seemed to be carved out of pale wood as his snapping eyes took in the swamp, with its groves of whispering alders, its margin of scattered birch-trees and swamp cedars, the lamplike sumac burning maliciously—the sinking boyish figure amid the moist green dreariness!

Now, Starrie Chase was by Nature’s gift more quick-witted than his companions, even than the trained boy scout.

“If we try to wade in toward him, we’ll sink ourselves!” he cried. “I’ll try to haul him out with that birch-tree.”

A leaping, plunging run, sinking to his ankles, and with the long bound of a gray squirrel he alighted upon the supple trunk of a tall white-birch sapling that grew within the borders of the swamp!

No squirrel ever climbed more rapidly than did he to its middle branches.

And the yellow flame in his eyes, now, was not a spark from persecution’s fire.

|

| “HELP! HELP!” |

“Hold on, Col! Keep up! The tree’ll pull you out. I’ll bend it down to you. When it comes within reach of your arms catch hold of the trunk! Hang on for your life! I’ll shin down, and ’twill hoist you up—you’re lighter than I am!”

He was bending the tall, supple trunk, with its leafy crown, down—down—as he spoke. It creaked beneath his fifteen-year-old weight. The strained roots groaned in the swampy soil.

“Gee! if the roots should give way I’ll land in the soup too,” was his piercing thought; and a shudder ran down his spine as he saw the pools of olive-green bog-soup beneath him—bottomless pools—in which floated slimy, stagnant things, leaves and dead insects.

Pools more horrible even than the patch of liquidescent mud in which Colin was sinking!

But Starrie Chase would never have attained to the leadership that was his among the boys of Exmouth if there had been nothing in him but the savage—the petty, not the primitive savage—that persecuted chipmunks and old women. Now the hero who slept in the shadow of the savage was aroused and there was “something doing”!

Lying flat upon the pliant sapling he forced it down with his heaving chest, with every ounce of will and weight in his strong body.

The silvery trunk bent to the sinking boy like a white angel.

With a cry he flung his arms upward and grasped it. At the same moment Leon slid down and jumped to a comparatively firm spot of the quagmire.

The flexible young tree rebounded slowly with the weight lighter than his pendant from it—like a stone attached to the boom of a derrick.

In a few seconds it was almost upright, with Colin Estey, mud-plastered to his arm-pits, hanging on like an olive-green bough, his dilated eyes starting from his head, his face blanched to the gray-white of the friendly trunk.

“Slide down now, Col, an’ jump—I’ll stand by to give you a hand!” cried Leon, the daring rescuer.

And in another minute the victim was safe on terra firma—out of the slimy throat of Big Swamp.

“Oh! I thought I was going—to sink down—out of sight!” he gasped between lips that did not seem to move, so tightly was the skin of his face stretched by terror. “That I’d be swallowed by the mud! I would have been—but for Leon!”

“You surely were quick! Quick as a flash!” The two boys who had been spectators gazed open-mouthed at Starrie Chase as if they saw the [Pg 59] hero who for three brief minutes had flashed out into the open.

“Whew! I got such a fright that I’ll never forget it; I declare I feel weak still,” mumbled Coombsie.

“Pooh! your fright—was nothing to mine,” Colin’s stiff lips began to tremble now with recovering life. “And I’m plastered with mud to my shoulder-blades—wet too! But I don’t care, as I’m out of it!” He glanced nervously toward Big Swamp, and at the clump of restless alders which probably still sheltered Raccoon Junior.

“The sun is quite hot here; let’s move back up the hill and sit down!” Nixon pointed to the grassy slope behind them where the crows still flapped their wings around the chestnut-tree with an occasional relieved “Caw!” “We’ll roll you over there, Col, and hang you out to dry!”

“Well! suppose we eat our lunch during the process, eh?” suggested Marcoo. “Goodness! wouldn’t it be ‘one on us’ if a fox had sneaked out of the woods and run off with the lunch-basket? We left it under the chestnut-tree.”

They made their way back to that nut-tree, whose hoary trunk was still swathed with Leon’s coat and the scout’s Norfolk jacket, knotted [Pg 60] round it to prevent the young coon which had signally outwitted them from “lighting down.”

“Whew! I feel as if ’twas low tide inside me. A scare always makes me hungry,” remarked Leon, not at all like a hero, but a very prosaic boy. “I think eating in the woods is the best part of the business!”

“I say! You’d make a jolly good scout; do you know it?” put forth Nixon.

But the other only hunched his shoulders with the grin of a contortionist as he bit into a ham sandwich, richly flavored with peanut butter and quince jelly from the shaking which the basket had undergone on its passage through the woods.

The troop of hungry crows which had pecked unavailingly at the wicker cover, had retired to some distance and watched the picnic in croaking envy.

Colin lay out in the sun, being rolled over at intervals by the scout, to dislodge the caking mud from his clothes, and to knead up his “soggy” spirits.

“Well! if we had carried out our first intention this morning, Nix, if we had gone down the river to the Sugarloaf Sand-Dunes near its mouth, we might all have stuck high and dry, in the [Pg 61] river mud, if the tide forsook us,” said Coombsie by and by, as he dispensed a limited amount of cold coffee from a pint bottle. “That’s a pleasure in store, whenever we can get Captain Andy to take us in his motor-boat. Say! he’s great; he was skipper of a Gloucester fishing schooner until a year ago, when he lost his vessel in a fog; the main-boom fell on him and broke his leg; he’s lame still. He stays in Exmouth with his daughter most o’ the time now. He was one o’ the Gloucester crackerjacks: he saved so many lives at sea that he used to be called the Ocean Patrol!”

“Why, he must be a regular sea-scout,” Nixon’s eye watered; he had the bump of hero-worship strongly developed.

“Captain Andy’s laying for you, Leon,” remarked Coombsie, passing round some jelly-roll.

“Oh, I guess I know why!” came the nonchalant answer. “It’s for tying a wooden shingle to a long branch of the apple-tree near old Ma’am Baldwin’s house, so that it would keep tapping on her door through the night. If the wind is in the right direction it works finely—keeps her guessing all the time! I’ve lain low among the marsh-grass and seen her come to the [Pg 62] door, in the dark, a dozen times, gruntin’ like a grizzly! I hate solitary cranks!”

“Captain Andy says that she was never peculiar as she is now, until her youngest son ran wild and was sent to a reformatory,” suggested Marcoo gravely.

“I’d cut out that trick, if I were you!” growled the scout.

“Oh! I don’t know; there are times when a fellow must paint the town red—or something—or ‘he’d bust’! That reminds me, we were going to daub ourselves with red from Varney’s Paintpot. If we’re to find it to-day, we’d better be moving on pretty soon. It must be after two o’clock now.”

“I haven’t got my watch on, but it’s quite that, or later,” the scout glanced upward at the brilliant afternoon sun.

“Hadn’t we better give up all idea of visiting the Paintpot or the Bear’s Den,” Marcoo suggested rather nervously, “and begin tramping homeward—if we can discover in which direction home lies? I think we ought to try and find some outlet from the woods.”

“So do I. Col will have a peck of swamp mud to carry round with him. His clothes are heavy and damp. If I only had my compass we could [Pg 63] steer a fairly straight course, for these woods lie to the southeast of the town; don’t they? Anybody got a watch on? I left mine at home.” Nixon looked eagerly at his companions.

“Our boy-scout handbook tells us how to use the watch as a compass by pointing the hour-hand to the sun and reckoning back halfway to noon, at which point the south would be.”

“My ‘timer’ is out of commission,” regretted Marcoo.

Neither of the other two boys possessed a watch.

“In that case we might trust to the dog to lead us out of the woods. We’d better just tell Blink to go home, and follow him; he’ll find his way out some time; won’t you, pup?” Nix stooped to fondle the tan ears of the terrier which had taken to him from the first, having never harbored the ghost of a suspicion of his being a “flowerpot fellow.”

The little dog stretched his jaws in a tired yawn. The pink pads of his paws were sore from much running, following up rabbit trails, and the rest. But the purple lights in his faithful brown eyes said plainly: “Leave it to me, fellows! Instinct can put it all over reason, just now!”

But Blink’s master started an opposition [Pg 64] movement. He had been invited to guide the expedition; he was averse to resigning such leadership to his terrier; in that case his supposed knowledge of the woods, of which he had boasted aforetime to the Exmouth boys, would henceforth be regarded as a “windy joke.”

“Follow Blink!” Thus he flouted the idea. “If we do, we won’t get out of these woods before midnight! He’ll dodge round after every live thing he sees, from a weasel to a grasshopper—like a regular will-o’-the-wisp. The sensible thing to do is to search for a logging-road—we’re sure to come to one in time—and follow that on. Or a stream—a stream would lead out on to the salt-marshes, to join the river.”

“There don’t appear to be any streams in these woods; they seem as dry as an attic!” Nixon, the scout, knew that the proposal now adopted by the majority was all wrong, contrary to the advice derived through his book from the great Chief Scout, Grand Master of Woodlore, but he hated to raise another fuss or make a split in the camp.

So the quartette of boys filed slowly up the slope and back into the woods, Coombsie carrying the almost empty basket, containing sparse remnants of the feast: “We may be hungry [Pg 65] before we arrive home!” he remarked, with involuntary foreboding in his tone.

That foreboding increased as they pressed on. Each one now became depressingly sure that he was wandering in the woods “lak wit’ eye shut”; without any knowledge of his bearings, or of how to retrace his steps to the log shanty flanked by the mountain of sawdust, whence he might be able to find his way back to the farm-clearing where he had encountered the musical woodchopper, frightened boy and dead raccoon.

The boy scout was silently reproaching himself for having fallen short of the prudent standard inculcated by his scout training. Carried away by the novelty of these strange woods and his equally strange companions, he had lowered the foresail of prudence—just tramped along blindly with the others—taking no note of landmarks, nor leaving any trace behind him that would serve to guide him back along the course by which he had come.

But, then, he had trusted to Leon’s leadership; and the latter’s boasted knowledge of the woods proved, as Coombsie had suspected, to consist of bluff as a chief ingredient!

“I wish I had kept my eyes open and noticed things as I came along, or that I had thought of [Pg 66] notching the trees at intervals with my penknife—blazing a trail—which we could have followed back,” lamented the scout. “I guess we’re only wandering round in a circle now; we’re not hitting a logging-road or trail of any kind. Tck! puppie,”—emitting an inarticulate summons between his tongue and palate,—”let’s see what’s the matter with those forepaws of yours! Blood, is it? Have you scratched them?”

He stooped to examine Blink’s slim white forelegs.

“Gee whiz! it isn’t blood—it’s clay—red clay: we must be on the trail of Varney’s Paintpot, fellows!”

So they were! They presently found it, that red-ochre bed, lying in obscurity among the bushes, scrub oak, dwarf pine and cedar, together with tall ferns, that stood guard over it jealously, in a particularly dense portion of the woods.

Once the clay had been vivid and valuable, with wonderful painting properties. Many an Indian had stained his arrow blood-red with it. Many a white man, an early settler, had painted the rude furniture of his home from that forest paintpot—then a moist tank of Nature’s pigment.

Later on it had been used too, as civilization progressed, and was claimed by the man whose name it bore.

Now, it was for the most part caked and dried up, its coloring power weakened; yet there were still moist and vivid spots such as that in which Blink, with the dog’s unerring instinct for scenting out the unusual, had smeared himself.

And those spots the boys promptly turned into a rouge-pot. They painted their own faces and each other’s, until more savage-looking red men these woods had never seen.

They forbore from delaying to smear their bodies, as Nixon had suggested, for one word was now booming in each tired brain like a foghorn through a mist: “Lost! Lost! Lost!” And they could not quite escape from it in this new diversion.

Still they tried to dye hope a fresh rose-color at this forest paintpot too: to silence with whooping yells and fantastic capers, and in flitting war-dances in and out among the trees, the grim raving of that word in their ears.

They painted Blink likewise in zebra-like stripes across his back, whereupon he promptly rolled on the ground, blurring his markings, [Pg 68] until he was a mottled and grotesque red-and-white object.

“He looks like a clown’s dog,” said Coombsie. “If any one should meet us in the woods, they’d think we were a troop of painted guys escaped from a circus! We’ll create a sensation in the town when we get home—if we ever do?” sotto voce. “Hadn’t we better stop ‘training on’ now, and try to get somewhere?”

So, controlling the training-on, capering savage now rampant in each one corresponding to his painted face, they toiled on again, while the afternoon shadows lengthened in the woods—until they stood transfixed, their war-whoops silenced, before another surprise of the woods on which they had tumbled, unprepared.

It was a lengthy gray cairn of stones with a rude wooden marker at the top bearing the date 1790, and at the foot a modern granite slab inscribed with the words: “Bishop’s Grave,” and the date of the stone’s erection.

“Bishop’s Grave!” Coombsie ejaculated, while the empty basket drooped heavily from his hand as if “the grasshopper had suddenly become a burden.” “I’ve heard of the grave, but I’ve never seen it before. Bishop was lost in these woods about a hundred and twenty-one [Pg 69] years ago; he couldn’t find his way out and wandered round till he died. His body was discovered months afterwards and they buried it here.”