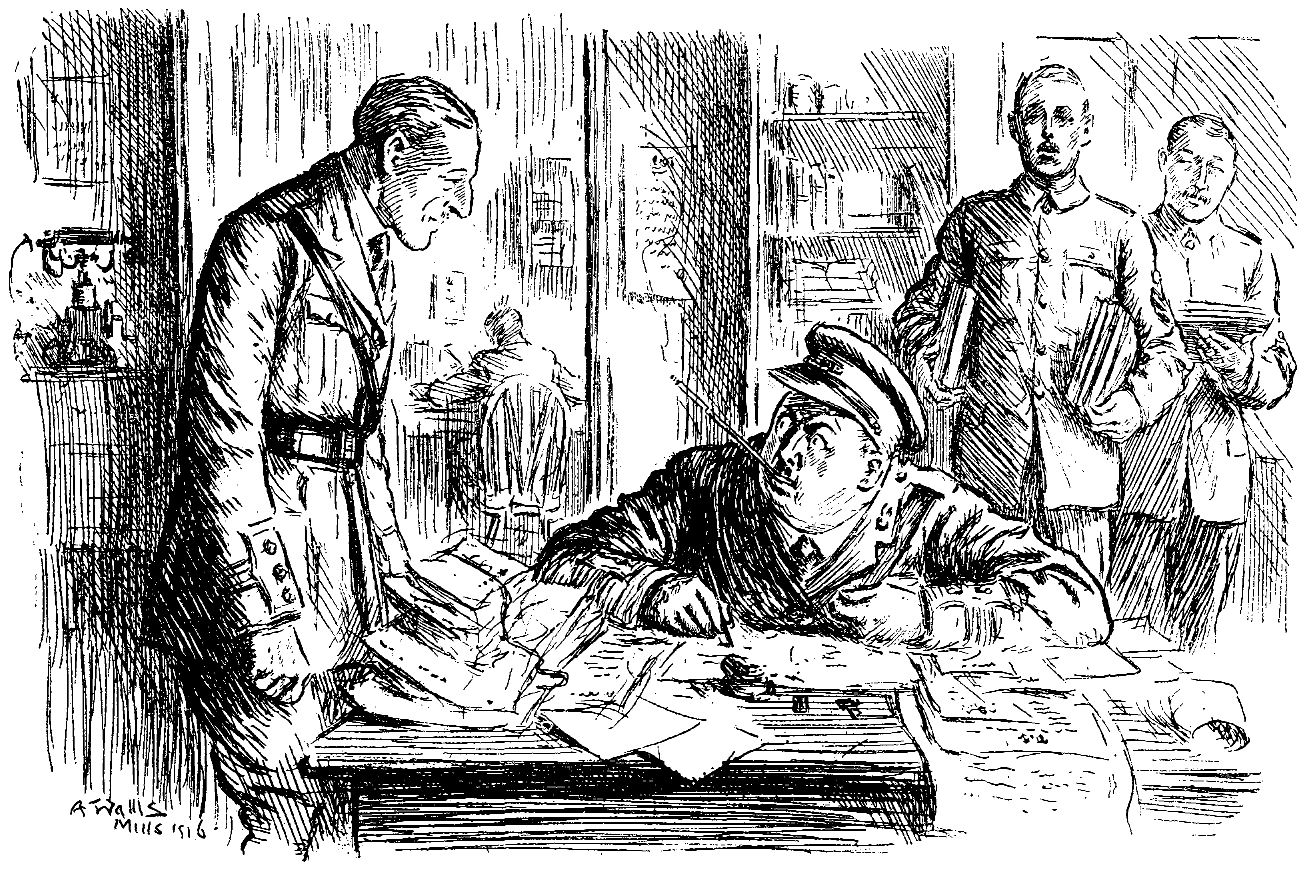

Overworked and exasperated Colonel (who has told Adjutant to answer the telephone). 'Well, what the blazes do they want?'

Adjutant. "It's the C.O. of the Blankshires, Sir; wants you to repeat the funny story you told him last night at mess."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or The London Charivari, Vol. 150, April 19, 1916, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Punch, or The London Charivari, Vol. 150, April 19, 1916 Author: Various Release Date: August 5, 2011 [EBook #36981] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, CHARIVARI, APR 19, 1916 *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David Garcia and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

CONTENTS: CHARIVARIA. — METHODS OF A GERMAN MISSIONARY. — UNWRITTEN LETTERS TO THE KAISER. — GRASS VALLEY ARMISTICE. — SAINT GEORGE OF ENGLAND. — GLORY O' ENGLAND. — THE ROLLING STONE. — ROUND ABOUT THE RESTAURANTS. — ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT. — A NIGHT OUT WITH A ZEPPELIN. — TO CHARLOTTE BRONTË. — AN UNRECORDED ENGAGEMENT. — ECONOMY IN THE PRESS. — NOT RUNNING TO SEED. — NURSERY RHYMES OF LONDON TOWN. — OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

Overworked and exasperated Colonel (who has told Adjutant to answer the telephone). 'Well, what the blazes do they want?'

Adjutant. "It's the C.O. of the Blankshires, Sir; wants you to repeat the funny story you told him last night at mess."

The recent Zeppelin raids have not been without their advantages. In a spirit of emulation an ambitious hen at Acton has laid an egg weighing 5-1/4 oz.

The opponents of Colonel Roosevelt regard the advice given in the title of his new book, Fear God and take your own part, to be unusually moderate as coming from one who, whatever he may have said to the contrary, is very generally suspected of being prepared to take the part that is at present being played by President Wilson.

At a meeting of the "No-Conscription Fellowship" last week, Mr. Philip Snowden referred to the Conscientious Objectors as the "Salt of the Earth." Perhaps, but we don't care to have them rubbed into us.

Germany has addressed a Note to the United States explaining that the Sussex could not possibly have been torpedoed for the reason that the submarine commander who sank the vessel had no difficulty in drawing a picture of her which closely resembled a totally different ship.

It is announced that the care of the great vine at Hampton Court has been taken over by the Office of Works from the Board of Green Cloth. It is rumoured that the latter body, which has been of late somewhat lost sight of, is to be entrusted with the general supervision of our aerial forces.

So successful have been the electrically-heated footwarmers supplied to the police of Pittsburg, Pa, that the State Department is said to be contemplating their adoption.

For shouting "The Zepps are coming!" a Grimsby girl has been fined £1. It was urged in defence that the girl suffered from hallucinations, one of which was that she was a daily newspaper proprietor.

While announcing in Parliament last week that the Zoo would have to pay the Amusement Tax the Chancellor promised to "keep an open mind in regard to any representations that might be made on the subject." Mr. McKenna, we understand, has since received a strong representation from the hippopotamus, protesting that, while he and his fellow-pachyderms are commonly considered as instructive, their natural dignity precludes them from attempting to provide amusement in any form.

"In twenty years' time," says Mr. Pemberton Billing, "the aeroplane will bring about universal peace." This statement will come as a distinct shock to many who imagined that with Mr. Billing at Westminster it might be expected to achieve this desirable result in about twenty days.

The Gaslight and Coke Co., in the interests of economy, are proposing to abandon the painting of street lamp-posts. The chief patrons of these institutions, they say, will be quite satisfied as long as the lamp-posts still feel the same to the touch.

A woman doctor has lately advanced the theory that talking leads to long life; but an attested married man of our acquaintance assures us that this is a mistake, and that it merely makes it seem longer.

"Bury Married Men and Lord Derby."

Provincial Paper.

A tempting solution of the Government's problem, but perhaps a little too mediæval for these times.

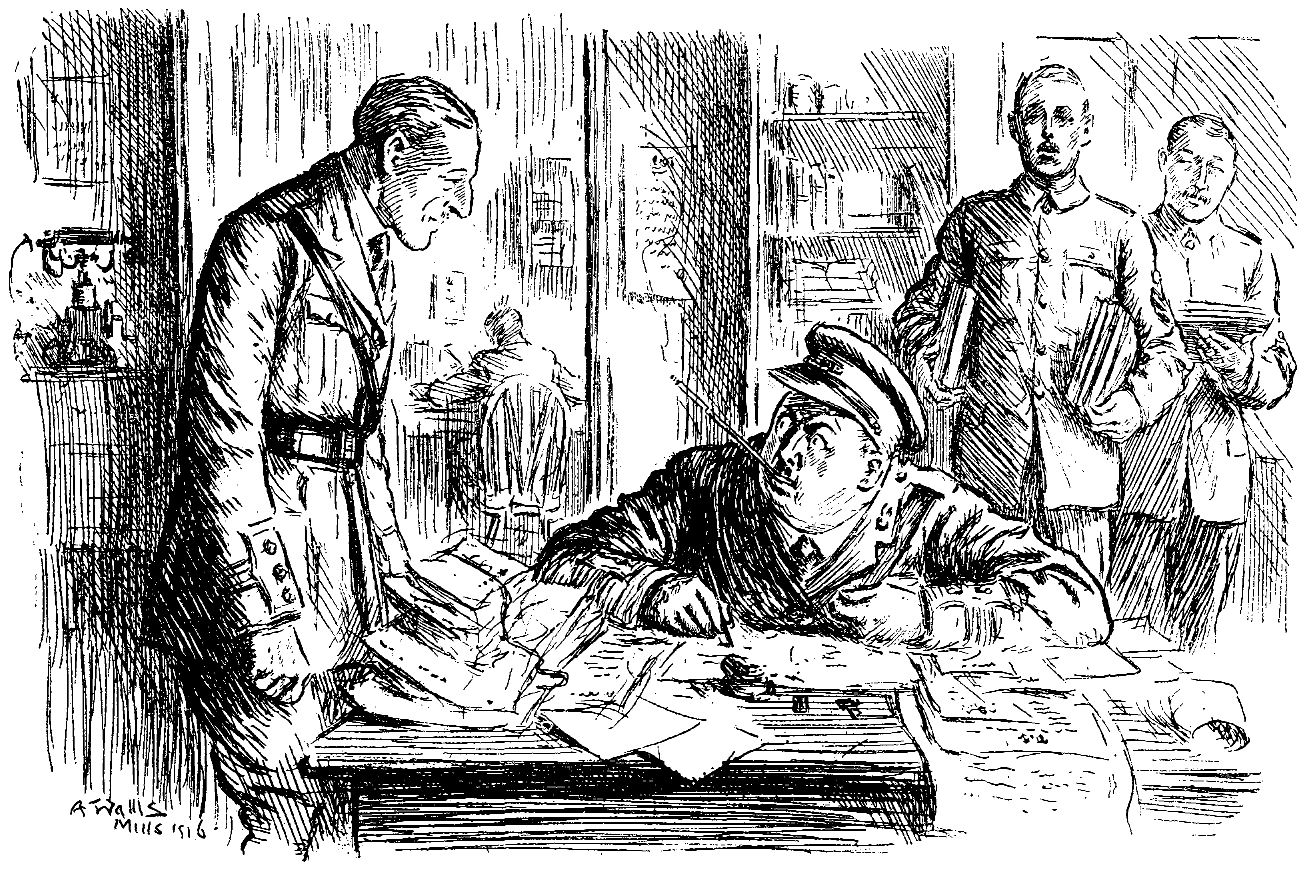

[See note to Cartoon on opposite page.]

The Sultan soliloquises:—

Mehmoud, the gilt is off your idol's crown;

Clear shows the clay beneath the chipped enamel;

In sporting phrase, your dibs have been planked down

On the wrong camel.

This William had a God he called his peer,

And yet must needs take on a new religion;

Spoke well of Allah; in His Shadow's ear

Cooed like a pigeon;

Pressed you to join him in a Holy War;

Advanced the wherewithal you badly needed;

And taught you how to go for Christian gore

The same as he did.

And now, where Afric's fountains fling their balm,

In his last place within the sun, 'tis written

With how remote a love for dear Islam

Your Bosch was bitten.

He hoped to stamp your creed out, branch and root;

This missionary meant to take your Arabs

And crush their souls beneath his mailéd boot

Like crawling scarabs.

And if they still ignored his ponderous heel,

If still their faith in Allah stood unshaken,

He looked to stimulate a local zeal

For heathen bacon!

Mehmoud, it is too much! Sick Man you are,

Yet in your veins I hope enough of vigour is

To tell this William he has gone too far

With his damned piggeries!

O. S.

(From Dr. Liebknecht.)

If such trifling matters as the meeting of the Reichstag now occupy any portion of your Majesty's attention, it may please you to learn that my membership of that august body has been temporarily suspended. At the same time I should be sorry that your Majesty should labour under any misapprehension as to what happened. No doubt I was forbidden to speak, though I am the representative of people whose voices have a right to be heard even in the unhappy Parliament which is all that the German Empire is allowed to provide for the subjects of the German Kaiser. But I wish you to understand that I was not silenced before I had said aloud nearly everything that I had in my mind to say. It is true that I did not make any formal speech. The bellowing blockheads who now arrogate to themselves the name of patriots and all the virtues of patriotism were easily able to prevent me from doing this, and I was forced, therefore, to confine myself to short and sharp interjections thrown in at appropriate moments while Bethmann-Hollweg, that arch-impostor, was proving to the whole world that even if Germany had a good case he is the last man who would be able to place it in a convincing manner before the judgment of the world.

Your Majesty has had a long practice in the use of words. You pride yourself on the glorious and beneficial effect of such speeches as that in which you condescendingly praised the Almighty for having allied Himself with you, very much, as it appeared, to His own advantage, or that other speech in which you announced to your conscripts their duty to shoot down their parents if in some momentary whim you ordered them to do it, or even that other brave and Imperial harangue in which you declared your humane and merciful designs on the Chinese people. I have no doubt, then, that if you could be induced to speak your opinion fairly and openly you would admit that, though you yourself could, of course, have done better, I did not do so very badly in my little bout with poor Bethmann. At any rate I spoke the truth, which is an inconvenient course of conduct, and made Bethmann look the fool that everybody (except, perhaps, your Majesty) knows him to be.

Indeed, your Majesty, a fool who is also arrogant is a very terrible thing. When Bethmann, for instance, spoke of Germany's love for her neighbours, and in particular for the small nations, he delivered himself into my hands. All I had to do—and I did it—was to remind him that he proved his love by jumping upon them and strangling them. In a moment the whole fabric of his stupid argument was shattered and he was left gaping open-mouthed and without an answer before the whole world. The incident showed the man's mind and his disposition in a lightning flash, and from all countries, even from wretched Belgium and from ruined Serbia, there came a laugh of hatred and contempt. Why are we so hated? Not because we are great and powerful and prosperous, but because we make our greatness an incubus, our power a tyranny and our prosperity an offence.

Fools like Bethmann do not see this. They and their fellow-fools, some of them quite brilliant men, with high notions on literature and music and the drama, are for ever in a state of jealous fear. They have the mania of persecution and imagine that all other countries are leagued against them for the purpose of wiping Germany off the map. Then they lose their unfortunate heads and strike out blindly to right and left. The other nations have no course open to them except to defend themselves as best they may, and then Herr Bethmann and his superior fools shout out that this wicked defensive proves up to the hilt that when they spoke of conspiracies they were fully justified and that Germany for her own safety must smash and in the end control every other country under the sun.

And yet, your Majesty, the time will come when we must have peace. This pouring out of blood, this tremendous waste of money and lives must some day have an end. Those are the best patriots who would put a stop to it as soon as possible, for the longer you defer peace the more difficult it becomes to make it. We have been told of great victories, but they profit us not at all. All is desolation and cruelty and confusion. And those who think most of Germany know best how bitterly she needs peace.

Your truth-telling but suspended subject,

Liebknecht.

"The Liar's Punishment.

"The Matin points out the predicament in which the German High Command must have found itself yesterday when editing its daily communiqué. No doubt it wished to place on record with all customary exaggeration the slight advantage gained on the slopes of the Dead Man. But how can the German High Command state this convincingly when for over a week it has solemnly announced the complete capture of the Dead Man? It has therefore to maintain silence as the only expedient."—Evening News.

On the principle: "De mortuis nil nisi bonum."

"We are told that the maximum of the income-tax duty will be reached at five shillings in the pound, a figure that will recall the Budgets of the Neapolitan wars."—Irish Paper.

When, as now, Vesuvians were so heavily taxed.

[Captured documents show that the German Government had schemed to stamp out Mohammedanism in East Africa both by force and by the encouragement of pig-breeding.]

"'E didn't mean to do it," he said, touching the bandages on his head. "Oh no, quite an accident. It was a foo-de-joy—doorin' the armistice. Wot, haven't you 'eard of Grass Valley Armistice?"

I said I couldn't recall it for the moment.

"It was doorin' September," he said; lasted two hours. Sergeant Duffin started it.

"'E was out on a patrol one night, and suddenly 'e comes rashin' back over the parapet and goes chargin' down to the Major's dug-out with a face like this 'ere sheet.

"'They'me comin',' ses Bints 'oo was next to me, and we were just goin' to loose off a round or two, when we 'eard ole Duffy 'ollerin' in the Major's bunk.

"'Barbed wire's gone, Sir,' 'e ses.

"'Wot?' ses the Major.

"''Ave to report the wire's gone,' ses Duffy again.

"'Tell Lootenant Bann,' drawls the ole man, as if someone 'ad told 'im tea was ready.

"When Bann 'ears the noos, 'e fires a light up.

"'Can't see none,' 'e mutters, quite annoyed, and off 'e goes over the top to find out for sure. In 'alf-an-hour 'e was back again.

"'The blighters 'ave pinched our wire,' 'e ses to the Major. 'They've drawed across them chevoo-der-freezes I put out, and stuck them on their own dirty scrap-'eap.'

"'Fetch 'em back,' says the Major, very off-'and like.

"'Right-O,' says Bann. 'Right-O.' For 'e'd spent three solid hours puttin' the wire out.

"'Fetch a pick an' some rope,' 'e ses to Duffy. 'I'm goin' to 'arpoon our wire.' Then he ties the rope to the 'andle of the pick and trots off over the parapet.

"After a bit we 'ears the pick land amongst the barbed wire with a rattle like a bike smash, an' the next minit back comes young Bann, sprintin' like a 'are an' uncoilin' the rope on the way.

"'Now then,' he shouts, jumpin' into the trench, 'man the rope!' an' we lines up ready down the communication trench. ''Aul away,' 'e 'ollers, an' back we goes, pullin' like transport-mules.

"It give a few inches to start with, an' then a foot or two, an' then, just when the wire must 'ave been 'alf-way 'ome it suddenly stuck fast.

"'Must 'ave caught on summat,' ses Bann, an' sets off with 'is wire-cutters to clear it.

"''Eave,' grunts ole Jones at the end of the rope. ''Eave-o, my 'earties,' an' then 'e knocks up against the ration-party comin' 'ome down the communication trench. ''Ang on, mates,' 'e shouts to them, an' down goes the bully bif, an' the next minit a loud rip an' some bad language told us 'is coat couldn't stand it.

"We got some more chaps at it then, but the rope never budged an inch.

"Then Bann comes runnin' back again, very excited-lookin'. 'Look out!' he shouts; 'the Bosches 'ave got a rope 'itched on, too.'

"Sure enough, the next minit the Germans puts their weight on, and pulls 'alf of us right over the bloomin' parapet.

"The Major comes along then, and when 'e sees the state of things 'e looks quite solemn, for there was only Lootenant Bann and ole Jones left in the trench.

"Where's the team?' 'e snaps, as severe as if you'd come on parade without your rifle.

"'Fall in, tug-o-war team,' sings out Duffy, and our eight, 'oo 'ad been lookin' on rather superior like, moistens their 'ands and stands to.

"'This is your work,' ses the Major to them, very significant.

"'Take the strain,' 'ollers Duffy, and the evenin' doo fair streamed out of the rope when they put their weight on. Back goes our team, two foot at least, whilst the lads cheers and yells as if we was winnin' the divisional prize on Salisbury Plain again.

"By this time the Bosches was just as excited as we were. They was rushin' about in the open with our men, 'owling their lingo and firin' off their rifles for encouragement. I stopped a shot somebody 'ad aimed at the sky for joy.

"When old Binks and the German chap 'oo 'ad done it was carryin' me back to our trench, I saw the Major come rushin' past.

"'Go it, men,' 'e sings out to our chaps, and then off 'e sprints again, to finish a bet he was makin' with the German officer.

"For an hour and a 'alf the excitement was awful. Up and down went that wire until the place looked like a ploughed field. First we gained an inch, then Germany 'ad a couple, then England gets one back, and up goes our caps again. Everybody was rushin' about yellin', and ole Binks, 'oo knows a bit of German, made a nice bit of money at interpretin'.

"Then things suddenly got worse. Our eight 'ung on like 'eroes, everyone swearin' 'e wouldn't loose that rope if 'e was pulled into the Kayser's bloomin' bedroom; but sure enough the Huns was slowly winnin'. Inch by inch we saw our chaps give way, black in the face at the notion of bein' beat. The Bosches yelled like 'eathens, and was shakin' hands with everybody. Then all of a sudden young Bann comes rushin' up to the Major, 'oo was takin' four to one with a chap from Coburg.

"'Stop, Sir!' I 'ears 'im shout. 'Stop the contest! The dirty blighters are usin' a windlass.'

"'Wot?' 'owls the Major, goin' purple at the thought of international laws bein' disregarded like that.

"'Take the men off the rope,' 'e orders. 'We hunderstood we was pullin' with gentlemen,' 'e ses very dignified, and then thinkin', no doubt, of the four to one in dollars 'e 'd 'ave won if they'd played fair 'e orders us to stand to and give them ten rounds rapid; and 'e used such language on the telephone that the Artillery thought we was attacked, and loosed off every shell they could lay hands on. So the War started again, you see.

He touched his head and thought a minute. "That was Grass Valley Armistice," he said finally, and relapsed into silence.

Street Hawker (to chatty old lady). "Yes, Mum, I'm being badly 'it. Yer see, all my bisness comes under the 'ead of luxuries."

"In Prize Court Attorney-General read affidavit showing there were gangs in Germany, America and other neutral countries engaged in evading our blockade."

Liverpool Echo.

It will take more than an affidavit to convince us that Germany is a neutral.

He. "That's Mannheim—chap I was speaking about."

She. "Made in Germany, I suppose?"

He. "No. Made in England—only born in Germany."

Saint George he was a fighting man, as all the tales do tell;

He fought a battle long ago, and fought it wondrous well;

With his helmet and his hauberk and his good cross-hilted sword,

Oh, he rode a-slaying Dragons to the glory of the Lord.

And when his time on earth was done he found he could not rest

Where the year is always Summer in the Islands of the Blest,

So back he came to earth again to see what he could do,

And they cradled him in England—

In England, April England—

Oh, they cradled him in England where the golden willows blew!

Saint George he was a fighting man and loved a fighting breed,

And whenever England wants him now he's ready to her need;

From Creçy field to Neuve Chapelle, he's there with hand and sword,

And he sailed with Drake from Devon to the glory of the Lord.

His arm is strong to smite the wrong and break the tyrant's pride;

He was there when Nelson triumphed, he was there when Gordon died;

He sees his Red-Cross ensign float on all the winds that blow,

But ah! his heart's in England—

In England, April England—

His heart it dreams of England where the golden willows grow.

Saint George he was a fighting man; he's here and fighting still,

While any wrong is yet to right or Dragon yet to kill;

And faith! he's finding work this day to suit his war-worn sword,

For he's strafing Huns in Flanders to the glory of the Lord!

Saint George he is a fighting man, but, when the fighting's past,

And dead amid the trampled fields the fiercest and the last

Of all the Dragons earth has known beneath his feet lies low,

Ah, his heart will turn to England—

To England, April England—

He'll come home to rest in England where the golden willows blow.

"Glory o' England, be passin', sure 'nough."

"She been passin' ever since I been 'ere to tell o' it, seems to me. 'Ow be she passin' now more 'n ordinary times, Luther Cherriman?"

"Way as is nearest to sudden death, George. 'Er young men gettin' that soft an' sloppy-like that there ain't no tellin' some of 'em from gals."

"Gals be comin' 'long won'erful—not much to complain o' wi' they. Drivin' motors, they be, an' diggin' an' all."

"Times be changin' fast; nigh time women wore the breeches an' done wi' it, now."

"I did think as our lads was doin' their bit middlin' well, too, out to Front. I did seem to 'ear they 'd counted f'r a German or two, first an' last."

"Fightin' Germans is a man's work just to present—if 'e be strong 'nough an' young 'nough an' all rest of it. But ye can't judge a man by 'is work 'lone, not to make a proper man of 'im. Sport did used to be the glory o' England, in my young days. An' now the young uns ain't got spunk 'nough to shoot a rabbit."

"That be an 'ard sayin', Luther, if ye like. 'Oo be you 'ludin' to partic'lar?"

"I be 'ludin' to young Squire—'oo did ought to set a good 'xample in this 'ere village, if anyone ought."

"'E were th' first to go when th' War broke out, though 'e be th' only son of 'is parents. An' more 'n 'alf of our chaps went 'cos of 'im, so 'tis said."

"That's all right, far as it goes——"

"I've 'eard say as 'e 've got a few more t' join ev'ry blessed time 'e've been 'ome on leave. They do say 'e be mortal keen."

"I don't say nothin' 'bout 'im shootin' Germans—I knows nothin' 'bout that. But in these 'ome fields I 'ave seen what I 'ave seen—no longer ago 'n yesterday."

"Be it too much to ask ye, then, what ye 'ave seen, Luther?"

"I seen a sight as tells me glory o' England be on th' wane. I seen young Squire loppin' 'bout 'ome fields an' 'is bits o' span'els at 'is 'eels same as ever. An' yet 'e looked that strange like I couldn't take m' eyes off of 'im. An' then it come over me all of a sudden what 'twas. 'Where be y'r gun, Sir?' I shouts to 'im over th' stile."

"What did 'e say to question personal as that?"

"'E come up to me an' I sees 'e got bunch o' daffodils in 'is 'and. 'These things smell o' Heaven,' 'e says, smilin' quiet. 'My gun is in the rack, Cherriman,' 'e says, 'where it's like to be.' 'Lor' love me, Sir,' says I, 'that do be strange, surelye, wi' th' rabbits 'oppin' 'round y' feet like a lot o' gals courtin' o' ye.' 'Strange,' 'e says; 'but we lives in strange times now, Cherriman. An' I've seen slaughter 'nough in Flanders to serve me for th' moment,' 'e says."

"'E said that?"

"'E did. An' white 'e went as 'e said it—you see the white comin' up under the brown of 'im."

"Pickin daffs?"

"Like some bloomin' gal."

"Didn't 'e say nothin' more?"

"'You dunno what it's like,' 'e says, 'to be back in this old place—to smell the good old Sussex clay, to watch the plovers flyin', to pick these flowers. You dunno what it's like, Cherriman,' 'e says, 'seein' you ain't come back to it from 'ell. Rabbits be safe 'nough from me now,' 'e says, an' drops his daffs all unknowin' like an' goes off at a mooney stride. An' 'e finest shot in th' county, some do say—an' I believes 'em!"

"Teh, Luther—stop yer jaw! There be young Squire a-comin'. An' bless me if 'e ain't ..."

"Here, you two old rascals, I've been looking for you—for you, anyhow, Cherriman. Here's a rabbit apiece for your suppers—shot 'em myself."

"Thank ye kindly, Sir. But I thought as you'd give up shootin'?"

"I thought so too, Cherriman—till I saw your face in the field yesterday. And then I said to myself, I must regain Cherriman's respect if it means the hardest bit of shooting I've ever done here or in Flanders."

"That's right, Sir! Don't do to let glory o' England die. Thank ye kindly for rabbits, Sir—us'll enjoy 'em proper."

"Hope you'll break your last tooth on them, Cherriman—that's what I hope."

"Glory o' England's more to me, Sir, 'n an 'ole set o' teeth at my time o' life."

"MARRIED MEN PROPOSALS EXPLAINED."

"Evening News" poster.

Are not these revelations just a little hard on our friends' wives?

The Art of Journalistic Expansion.

"The 'Russky Invalid' states: 'The Caucasus army has performed a miracle which in military history will be remembered for years to come.'"—The Age (Melbourne).

"'General Russky, though an invalid, and his Caucasus army,' declares The Messenger, 'have performed a miracle which military history will remember for years to come.'"

The Argus (Melbourne).

At Cambridge, where on field or flood

He shone like a Goldie or a Studd,

He was an intellectual "blood."

He made the grimmest dons unbend,

And missed his First, right at the end,

For he cut his Tripos—to nurse a friend.

Then he wrote a novel. The weekly press

Declared it was worthy of R.L.S.;

But it wasn't a great financial success.

So, after a spell at the Bar, he flew

To the rubber-fields in remote Peru,

But stayed there only a month or two.

For he suddenly conceived a plan

Of studying music at Milan,

Where he sang in the style of the great god Pan.

I heard him sing in the Albert Hall

In the chorus of Mendelssohn's St. Paul,

And his voice was the loudest of them all.

Next he leased a Colorado mine,

And dealt in Californian wine,

And rented a ranche in the Argentine.

But whatever the job and whatever the pay

I certainly never knew him to stay

Anywhere as long as a year and a day—

Except one job, which is not yet done,

Though twenty months ago begun,

Of holding and hammering the Hun.

His horoscope I have never scanned,

But as long as there's any fighting on hand

The rolling stone has come to a stand.

Irreplaceable.

Evidence of a conscientious and candid objector:—

"I am sure the Rector could not get anyone to take my place, as Cowley is now empty, and there are no loafers about."

Gloucester Citizen.

"The first cases to come before the tribunal were appeals from three Thirsk butchers, for the exemption of their respective slaughtermen. Mr. Johnson said he killed himself about 20 years ago. He thought he would start again."—Darlington and Stockton Times.

Very difficult to repeat the first fine careless rapture of a successful suicide.

"No, while it is a crime to spend money extravagantly on dress, it is just as emphatically one to abstain from it altogether."

Daily Chronicle.

If The Daily Chronicle says so, we accept it. There is no paper for whose judgment we have a more profound regard.

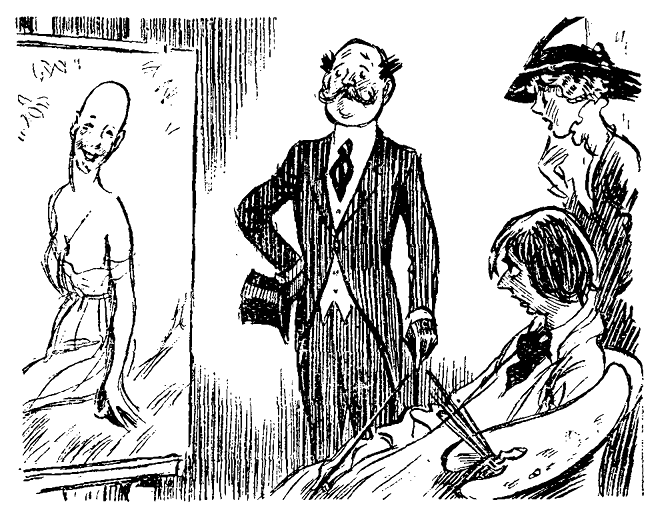

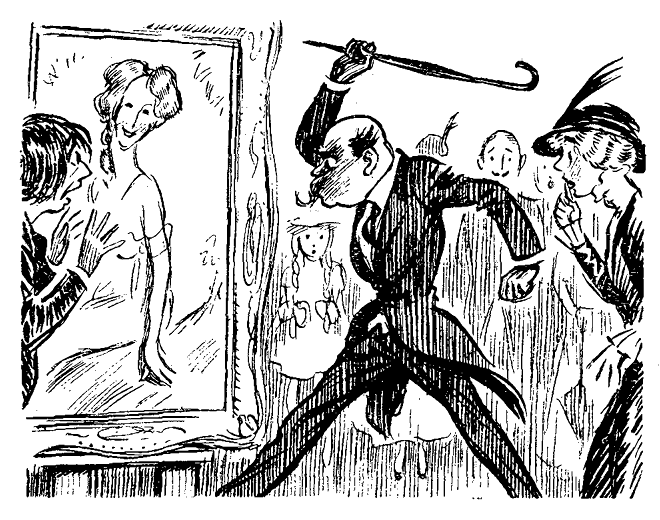

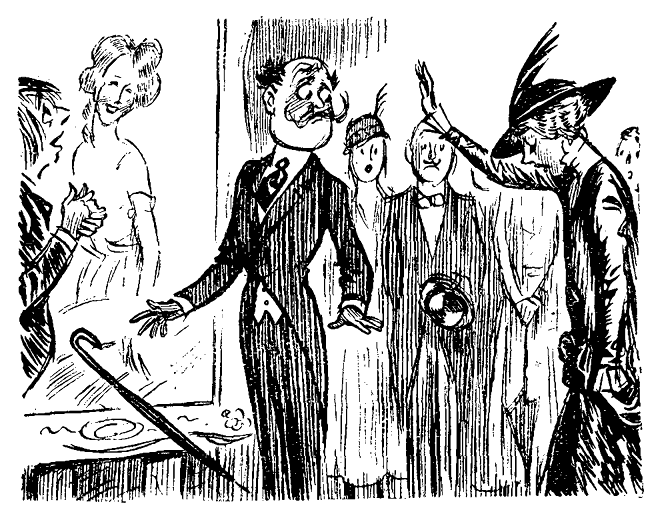

Clarence Allardyce, the rising young artist, cannot in all London find a model worthy to pose for the hair in his masterpiece, 'The Wood Nymph.' On the eve of the exhibition he tells his trouble to his friend, Charles Carfax, who, with his fiancée, has visited the studio.

The next day a fashionable crowd throngs Allardyce's studio to view the picture before its departure to the exhibition. Among them is Carfax, who, recognising his fiancée's hair, is overcome with rage and threatens to destroy the picture.

As he is about to execute his fell purpose he is stopped by his fiancée. 'Stay!' she cries. 'It is not as you suppose. It is my hair, but—I wear a wig. I sent it to him by post.' By this noble lie she saves the picture at the cost of her matrimonial hopes.

Cast off by Carfax, the heroine visits the exhibition alone. There she is found by Clarence, who asks her to share with him the fame and fortune which she has brought him.

Face Massage Specialist. 'No doubt, Sir, your speeches on Frightfulness have affected your expression.'

Prussian Orator. "Well, you must do the best you can for me. To-night I have to speak on 'Our Love for the Smaller Nations.'"

The famous Quex having relinquished the raree show of London—its lunches, its beauties, its theatres, its celebrities and its suppers—to take part in this boring and extremely inconvenient War, how proper that he should be succeeded by a younger flâneur! Behold then Quex minimus busy as a chronicler in your service.

Met Sir Loney Loon at the Fitz, where I had the greatest difficulty in finding a host. Succeeded, however, at last, but as he was an unknown person I do not mention him here. Sir Loney told me he was thinking of standing as Independent candidate when next there is a vacancy, being so utterly tired of the Coalition and all its incompetencies. Fancy, said he, after at least ten years of existence, aviation not being perfect! And the iniquity of any hitch whatever in any department after nearly two years of war! All I can say is I hope the famous magnate wins.

Heard Lord and Lady Provender eating their soup at the Barlton grill, where I had an excellent position behind the screen. His lordship looks older than he did in 1893, when he was in India. Her ladyship was wearing the famous Sheepshanks agates.

Talked to Dicky Post, the famous trainer, after Newmarket. He said it was most gratifying to see how finely racing men took the War. No one could visit the historic course and not realise what a wonderful country England was. To see the jockeys doing their bit on this mount and that, no matter how they might kick or plunge or buck, was a real tonic and indicated what stuff they were made of. He said that M. Humbert's recent article on the need for the Allies of France to be as much in earnest as she was, had a very favourable reception on the Heath.

Met, at Liro's, Harry Wagtail, who is the author of most of the best bons mots of the day, although they go into circulation usually under other men's names. Paying the new income-tax, he said, will be like selling the gold in your teeth to discharge the dentist's bill.

Watched a famous millionaire at the Vasoy wondering whether he dare flout public opinion and the economy campaign by eating a plover's egg. Finally he got under the table to eat it unperceived, and was most surprised to find me there.

Quex minimus.

"Might be due to Pictures.

"Magistrate and three Leeds youths charged with warehouse-breaking,"

Yorkshire Evening News.

We regret to see that the demoralizing influence of the cinema appears to have extended to the Bench.

"On arrival at the Hook there was nothing left whatever in the way of eatables, and even the greater part of those saved were still in their nightdresses."—Scotsman.

Pommes de terre en robe de chambre, we presume.

"A Memory.—Thirty-nine years ago Miss Mary Rorke was playing with John Hare, now Sir John, in the famous old play, 'Old Men and New Acres.'"—Daily Paper.

A treacherous memory.

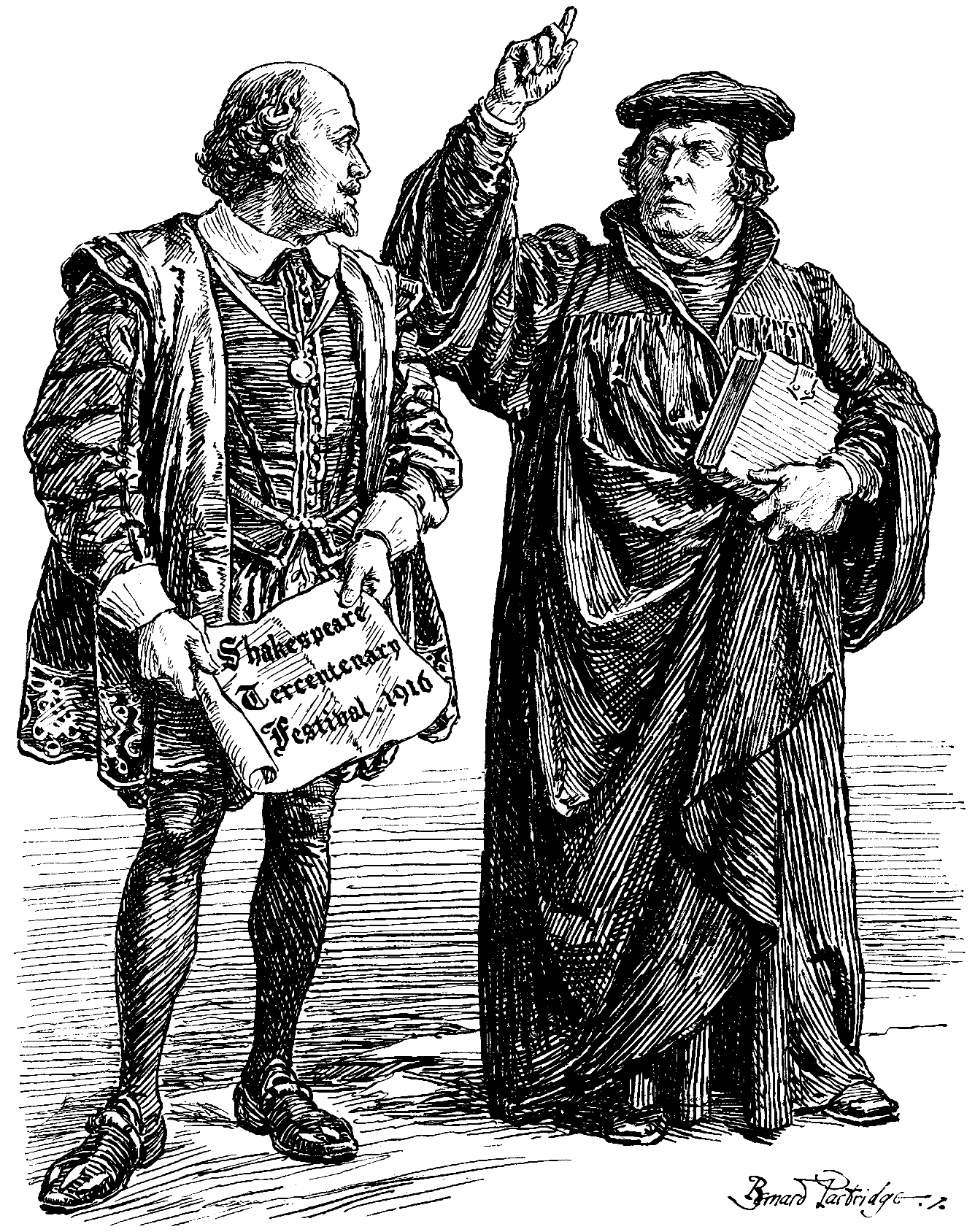

Martin Luther (to Shakespeare). "I SEE MY COUNTRYMEN CLAIM YOU AS ONE OF THEM. YOU MAY THANK GOD THAT YOU'RE NOT THAT. THEY HAVE MADE MY WITTENBERG—AY, AND ALL GERMANY—TO STINK IN MY NOSTRILS."

Monday, April 10th.—Some sadness mingled with the cheers that greeted the moving of the writ for the Wimbledon Division. The House is pleased that Mr. Henry Chaplin's long services to the State should have received the customary reward of a peerage, but it will miss his genial and majestic presence. Though an unfortunate accident in 1906 (a year prolific in electoral casualties) debarred him from becoming the titular Father of the House, his venerable appearance, his courtly and old-world bearing, and his full-bodied eloquence gave him an uncontested claim to be regarded as its Grandfather. Lord Claud Hamilton, the only other survivor of the Parliament of 1868, will now feel very lonely.

The best things said at a public meeting are often uttered by an anonymous "Voice." Mr. Will Thorne is the "Voice" of the House of Commons. Endowed with a fine pair of lungs and a style of delivery that resembles the cork coming out of a ginger-beer bottle he frequently expresses in his explosive style the collective opinion of his fellow-Members. At Question time Lord Robert Cecil referred to the abominable treatment of British prisoners of war at the Wittenberg camp, and said that steps were being taken to circulate in neutral countries the report of Mr. Justice Younger's Committee. There was a sudden "Pop," and out came Mr. Thorne with "Send it to the conscientious objectors."

On the Second Reading of the Budget Mr. Thomas O'Connor, as the Speaker punctiliously calls him, led off with a vigorous attack upon the match-tax. The discovery, made many years ago, that match-making as then conducted caused a painful disease of the jaw first aroused T.P.'s sympathetic interest. He now displayed an intimate acquaintance with the details of the industry and discoursed learnedly on the shortage of muriate of potash for the heads and of aspen for the splints. His argument briefly amounted to this—that the manufacturers of matches, like those of mustard, depended for their profits upon the amount wasted, and that to check public extravagance would destroy the trade.

The aspens on the Treasury Bench did not quiver visibly under this assault. They were more amenable to the criticisms on the railway-tax, which would fall very hardly upon commercial travellers and other business people. Mr. McKenna promised to give careful consideration to the criticisms before the Committee stage. Possibly it has occurred to him that as the Government have undertaken to bring the net receipts of the railway companies up to the 1914 level the Exchequer might have to pay out of one pocket nearly as much as it puts into the other.

Tuesday, April 11th.—One of the French Deputies visiting Westminster thinks us a queer people. He had heard last night the Prime Minister's stout declaration of the Allies' resolve to bring Prussia's military domination to an end. Again this afternoon he had been told on the same high authority that the late Conference in Paris had reaffirmed the entire solidarity of the Allies and established the complete identity of their views. Then he had walked across the corridor to the House of Lords, expecting, no doubt, to hear the same sentiments expressed in even loftier language. Instead, he had to listen to Lord Courtney, in the traditional yellow waistcoat, declaiming with all the vigour of his premiere jaunesse against the notion that we should enter into any fiscal relations with our Allies that might imperil the sacred principles of Free Trade.

Lord Courtney believes that there is in Germany a large and powerful peace-party, which must not be frightened by any threats of reprisals, and he commends to the Allies in 1916 the example of Bismarck in letting the Austrians off easily in 1866. Our visitor was a little relieved by the explanation that the orator was an interesting survival of a school of thought now passed away, and represented no one but himself. But he was again puzzled when Lord Bryce, who knows as much about the manners of the gentle Hun as anybody (witness his report on the atrocities in Belgium), joined in the appeal that we should be nice to Germany after the War.

He was, however, somewhat comforted when Lord Crewe made it plain that the Government did not share Lord Courtney's illusions about the strength of the German peace-party, and, having regard to the manner in which Germany had in the past combined commercial expansion with political intrigue, could not hold out hopes that after the War we should do business with her in the same old easy-going way. But if our French friend is still not quite convinced that British [267] statesmen fully realize what the War means to him and his country I don't I think we can altogether blame him.

"I am unable to say what steps the married men may take to track the single."—Mr. Tennant, in the House.

In the Commons Mr. Pemberton Billing developed his usual Tuesday "hate." But on this occasion there was no reply from the Government heavy batteries; little Mr. Rea explaining that as the Hon. Member had failed to warn them of his intention to bombard they had no ammunition ready.

Wednesday, April 12th.—Although, like another noble Earl, Lord Selborne is "not an agricultural labourer," he does his best to play the part, and save our food-producers from the maw of the hungry recruiting officer. A representative of the Board of Agriculture now holds a watching brief at every local Tribunal, to see that the Military representative does not have things too much his own way. No wonder that the taxes mount up faster than the recruiting returns.

Time was when Mr. Swift MacNeill successfully dissembled his affection for the House of Lords. To-day his principal object in life is to purge the roll of that illustrious House of the peerages now held by the enemy Dukes of Cumberland and Albany. The Prime Minister was strangely unsympathetic. Legislation would be necessary, and would occupy too much time. "Three minutes," suggested Sir Arthur Markham; but Mr. Asquith was still obdurate, and seemed to think that as the Dukes in question had lost their Garters they were sufficiently down-at-heel already.

When packing his Budget a wise Chancellor of the Exchequer always includes some little tit-bit that he can throw to the wolves if they become too insistent. In the present case the tax on railway tickets was marked for abandonment at the outset, and to-day it met its expected fate.

The Amusements tax was strenuously opposed by Mr. Barnes, on the ground that most of the money would come from the poor; but Mr. McKenna frankly replied that that was just what he intended. He agreed, however, to consider the claim of the Zoo to exemption. The match-makers were partially appeased by a promise that mechanical lighters should not be overlooked. The Chancellor is now in some doubt as to whether he or Æschylus has produced the more notable version of "Prometheus Bound."

Thursday, April 13th.—A provincial paper lately referred to Mr. McKenna as the "Cancellor"—a humorous compositor's way, no doubt, of indicating the modifications in the Budget. Hardly one of the proposed new taxes has survived intact. Even the tax on mineral waters has had to undergo considerable alteration. It was devised to get some contribution towards the nation's needs from those who wear the blue ribbon of a beerless life, and to that end the tax was to be collected by means of a stamp on each individual bottle. But the manufacturers successfully protested that the boys and girls who affix the labels already adorning these gaseous wares could not be trusted to put on stamps as well. Mr. Montagu announced this afternoon that the manufacturers would be taxed direct on their certified output. But he did so with obvious reluctance, and as if what was once a sparkling proposition had become indubitably flat and possibly unprofitable.

Our Stylists.

"Now and again a mirthless laugh rose silently to the red banks of her lips."

Grand Magazine.

Signature to a legal notice:—

"Montgomeryshire Horse Repository, E.C., Solicitors for the said Administratrix."

Manchester Guardian.

If "the law is a hass" you are tempted to say, These equine attorneys will answer, "Neigh, neigh."

Fashions for Female Humourists.

"Blouses of the useful variety have jokes in various designs, the sleeves cut in one with the joke are generally a modification."

Provincial Paper.

Our more subtle contributors prefer the latter kind, enabling them to laugh up their sleeve.

Constable (failing to notice insignia of 'Special'). 'Nah, then, you! Get a move on yer unless yer wants to be run in for loitering!'

(HYPHENATED NEUTRAL).

Part I.

Somewhere in Germany,

April 1st, 1916.

I had just partaken of the frugal breakfast to which I had been invited General Headquarters and was in the act of helping my distinguished host, Feldmarschall von und zu Grosskopf-Esel, to remove some fragments of sauerkraut from his ears, when a superbly-mounted orderly dashed up and handed me a missive bearing the significant superscription, "General Staff." I must confess that to me the messenger's manner seemed sufficiently deferential. Not to my friend the Major-General, who, with a sudden and well-placed kick in the stomach, sent the unfortunate despatch-bearer hurtling down the steps. It was not for me to inquire what the trouble was, and I mention the incident as one more illustration of the iron discipline that has driven the gallant troops of the Fatherland to victory on all fronts.

Imagine my gratification on finding that the letter was an invitation to inspect on the following morning the latest Zeppelin sheds at —— and to be a passenger on board one of the new airships that was scheduled to pay a surprise visit to the fortress of London that same evening, weather permitting.

Punctually at seven on the following morning I found von und zu Grosskopf-Esel waiting for me in the huge twenty-cylinder roadster which the General Staff customarily places at the disposal of American newspaper correspondents. Within the hour we were at ——, where I was turned over to the good offices of Herr Ober-Leutnant von Dachswurst, of the Imperial Flying Corps, who immediately conducted me to the shed from which (when the weather is propitious) the aerial monsters depart upon their errands of doom.

I had expected to see two, or at most three, Zeppelins in the great shed. Imagine my astonishment on beholding no fewer than a hundred huge engines of destruction tugging impatiently at their moorings. I was speechless. But the Ober-Leutnant read my thoughts. "What would you say," he asked, smiling drily, "if I were to tell you that Germany to-day possesses no fewer than one hundred such fleets of airships as you see before you?" So overcome was I that I scarcely had the strength to ask him why, up to that time, attacks had been usually carried out with two or three ships only. He smiled still more at enigmatically. "You must not ask me that," he said, "or at least you must first ask the Grand Admiral why his five hundred submersible battle cruisers are still at anchor in Kiel Harbour, or the General Staff why five million of Germany's finest veteran troops are still doing the goose-step in the Potsdam Thiergarten, or Herr Helfferich why the rate of exchange has not been corrected by releasing some small portion of the ten thousand billion marks that lie in the Imperial treasury at Spandau! Be patient," he added. "Our perfidious enemies will bite the dust whenever it suits our glorious leaders to say the word."

I muttered something about the enormous German casualty lists. The Ober-Leutnant smiled more enigmatically than ever. "A ruse to deceive our enemies," he said. "Would it surprise you to know that up to date the total German losses on all fronts amount to seventeen killed and ninety-one wounded and missing, while our material losses have so far been confined to three field guns left over from the Franco-German War and five dozen cases of collapsible sausage rolls?"

It was incredible, yet I could not but accept the statement as true, and have in fact had ample opportunity since of verifying the assertions of the gallant officer.

"But come," he said; "it is time we were on board."

The Zeppelins that were actually selected to conduct the proposed operations were housed in another shed, and thither we repaired. We were greeted at the gangway by the famous Captain Sigismund von Münchhausen, a gruff but hearty old mariner, who immediately escorted me into his cabin and insisted on my enjoying a cigar and a glass of schnapps with him. Once again I was struck with that almost Oriental charm of manner which seems to lift the German Higher Command above the plane occupied by the rest of the Occidental world.

It was no doubt my impatience that caused me to interrupt the gallant Captain's delightful flow of racy anecdote to ask when we should start. My host smiled enigmatically. "By now," he said, "we should be somewhere over the Dogger Bank."

It was true. So perfectly had all things been appointed that while I had been consuming a single glass of schnapps the huge airship had completed half the journey.

We now emerged from the cabin. As we approached the rail a sailor stepped up to the Captain, saluted and asked permission to speak. As far as I could gather, the wretched man complained of seasickness and asked to be put ashore. There was no mistaking the Captain's answer. "Ja wohl!" he roared, and with a mighty kick sent the luckless seaman hurtling over the rail and into the abyss below. A momentary sense of pity seized me, but it quickly occurred to me that only by such drastic means could be kept alive the splendid spirit of chivalry that has made the German airman victorious throughout the firmament.

It was now quite dark, but far beneath us could be seen with the aid of a telescope little points of light. Perfidious England, the author of all Germany's troubles, lay helpless beneath us.

(To be continued.)

'You advertised as chauffeurette-maid.'

"Yes, Madam."

"What were your duties at your last place?"

"I drove and cleaned the cars single-handed."

"And as maid?"

"I took down my lady at night and assembled her in the morning, Madam."

Strange that the most farouche of all the ladies

Rightly renowned as drivers of the quill,

Who hated all publicity like Hades,

And showed in self-advancement little skill,

Who did not write for Smiths and Browns and Bradys,

But at the prompting of her own sweet will—

Her most obsequious partisans should find

In penmen of the parasitic kind.

In vain did Mrs. Gaskell, wise and gracious,

Paint us your portrait, delicate yet true;

Sensation-mongers, strident and voracious,

Must needs explore your inner life anew,

Clutching with fingers ruthlessly tenacious

At the remotest semblance of a clue;

Raking the dustbins for unprinted matter,

And prodigal of cheap and tasteless chatter.

And now in days of endless storms and stresses

Comes your Centenary, with odes and lays,

And lantern slides and lectures and addresses,

And all the modern ritual of praise;

With columns in The Sphere of C. K. S.'s

Comments upon your life and work and ways,

Judicial summings-up of old disputes

And photographs of Patrick Brontë's boots.

And men and maids will doubtless march with banners

To prove their worship of your "massive brain";

And intellectual Chicago "canners"

Will send their relics from across the main;

And critics will discuss your various manners,

And Harold Begbie will pronounce you "sane";

In short, you'll be the bookman's prey and quarry

At many a high-class literary "swarry."

Well, well, brave Charlotte, though our admiration

Prompts some of us your memory to revere

In ways less vocal in their adulation,

You will not hold our homage less sincere

If we refrain from pouring a libation

In orthodox Centenary small-beer,

But choose to greet in silent awe and wonder

The stormy spirit of the child of Thunder.

Commercial Candour.

"Messrs. —— & Co., Ltd., Court Dress-fakers, &c."

Provincial Paper.

"Our Youngest General.

"He was educated at Glasgow University and Gottingen University, and entered the army in 1716."—Bangalore Daily Post.

Our Indian contemporary is misinformed. Several of our Generals are younger than that.

The following interesting letter has been forwarded to us by the relatives of one of our wounded heroes. It gives a vivid idea of his impressions during a severe engagement, particulars of which have not so far appeared in the Press.

"Red Cross Hospital,

Somewhere in England.

"... And now I must tell you of a very hot time that our lot here had recently. The attack was due to open at 5.30 in the afternoon. We had been warned to expect it, and the appointed hour found us ready in our positions. We were five deep, strongly posted on deck chairs; moreover, the warning had given us opportunity to construct a defensive rampart of evergreens and pot-plants before the front line.

"The engagement opened fairly punctually with a furious pianoforte bombardment, accompanied by asphyxiating footlights. Owing to the closeness of the range and the weight of metal employed, our first rank gave way a little, but subsequently rallied smartly. The attack now became general, the enemy advancing first in detached units, subsequently in column or quartette formation. A stubborn resistance was put up, but we were nearly forced to recoil before a desperate charge by The Men of Harlech.

"Hardly had we contrived to withstand these, when, with blood-curdling cries, the Funny Men dashed forward and fell upon us. The engagement was at this point so fierce that it was impossible to obtain more than a confused impression of it. I saw several of my brave comrades doubled up. Puns and lachrymatory wheezes darkened the air. At last, after a specially violent offensive, in which he was supported by the full strength of his piano, the enemy retired, followed by salvoes from our ranks, and left us, at least temporarily, masters of the situation.

"A lull ensued, during which, however, in spite of the curtain behind which the enemy endeavoured to mask his preparations, we were convinced, from certain unmistakable signs, that a fresh and possibly more violent attack was shortly to develop. Nor was this view wrong; for, when the curtain lifted, we at once saw that our worst fears were justified. Confronting us were the 1st Amateur Thespians, the most dreaded battalion in the enemy's Volunteer forces, and one reputed to have decimated more British classics than any two professional regiments.

"The methods of this body have changed very little during the last half-century. They still employ for choice the old Box-and-Cox attack, which has proved so effective in the past, followed frequently by A Case for Eviction or else Gentlemen Boarders. Bold to the point of rashness, no difficulties are found to daunt them; and the stoutest hearts might well quail at being exposed to the fury of their onslaught. Indeed how any of us survived the half-hour that followed I hardly know. It was a nightmare of smashed china, dropped cups, shouts of 'Bouncer, Bouncer!' and general confusion.

"But time was on our side; and when, towards seven o'clock, the curtain fell again, we knew that, holding as we did almost our original positions, we were victorious. Our exact casualties I have not yet heard, but they are certain to have been heavy. The ground lately held by the enemy presented a spectacle of appalling confusion; and everything pointed to the struggle having been most determined. Restoratives were administered to our men, and we turned in, exhausted but happy."

It has been noticed by close observers that among curious developments brought about by the War the personal advertisements have been growing increasingly intimate. Mars and Venus again are associated. So far, only the Classes have been conspicuous. Why not the Masses too? Something like this:—

Will Lady wearing handsome garnet necklace and ostrich feathers in large hat in front row of gallery of Britannia Theatre, who threw orange at Gordon Highlander in pit, injuring his left eye, meet him Sunday evening, Marble Arch, 7 sharp?—Box F.3.

Will Girl seated second table on left at Lockhart's, 17th April, 6.30, eating cold meat-pie, communicate with Bedfordshire Corporal with arm in sling, two tables away?—Box 183.

Lonely Married Man invites correspondence while waiting for single men to do their duty.—Box 84.

Saw you marching past Charing Cross Station, three a-breast, whistling "Keep the Home Fires Burning," Saturday night at 10.15, and called out to you from top of omnibus. Please write.—Box 10.

"Lost, gold CHAIN and PENDANT, containing sailor and baby; 5/- reward."

Liverpool Echo.

Small enough, even for the baby.

I.—The Editorial Page.

Here upon our middle page,

Where the correspondents rage,

Grim and dour and dry,

Here with counsel bold and sage

War on lollipops we wage,

Smiting hip and thigh.

"Pare potatoes very thin;

All the virtue's in the skin;

Save the peel for soups;

Drop cigars; abandon gin;

Leave the bristles on your chin;

Tie your hair in loops.

"Golf and ties and collars shun;

Lunch upon a penny bun;

Butter not your bread;

Save your pennies—every one

Helps to crush the brutal Hun."

Thus and thus we've said.

II.—The Advertisement Pages.

Now the advertiser comes;

Hush the sound of warning drums;

Hear his siren song:

"Leave your economic sums;

Leave the task of saving crumbs;

Join the shopping throng.

"Come to Blank's—the thing to do!

Here are chiffons, ninons too,

Quilts for Fido's cot;

Silken robe and satin shoe,

Figured fabrics, gold and blue,

Bangles, pearls—what not?

"Bon-bons, perfumes, trifles gay—

Still you'll find a fresh display

Where the last one ends;

New sensations every day!

Motor round without delay!

Come, and bring your friends!"

In Its Proper Element.

"No appointments have been made in the place of Lord Derby and Lord Montagu [who have resigned their seats on the Joint Air Committee], and the Committee is, for the present, en l'air."—The Times.

"Amongst the sights which never fail to draw the attention of curious Londoners is that of girls perched high up on enormous vans manipulating the reins and guiding fresh nurses through the maze of city traffic."

"Star" (Ch. Ch. N. Z.)

There must be some mistake here. The nurses we see in London are always perfectly sober.

Mr. Blatchford on the match-tax:—

"In this insidious manipulation of the thin end of the Tory wedge do we not perceive the cloven hoof of the serpent casting its shadow before?"—Weekly Dispatch.

No; all we see is Mr. Blatchford laboriously trying to emulate Sir Boyle Roche.

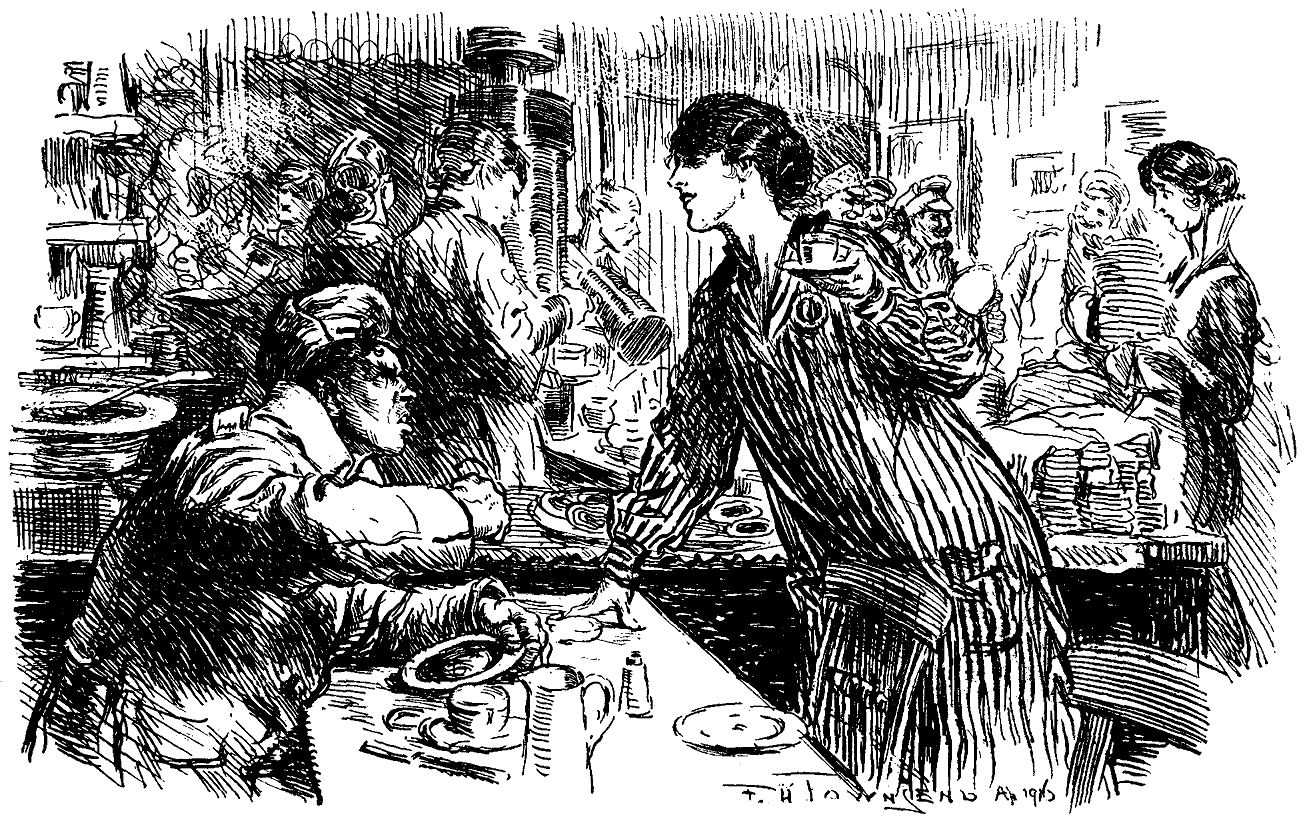

Tommy. "I went to a place a bit further down the road for supper last night. I don't go there again."

Lady Muriel Beltravers-Montmorency. "Oh, what's the matter with it?"

Tommy. "What's the matter with it? Why, they have paid waitresses there."

Dear Sir (or Madam),—Looking over our records a few days ago, we noticed that you had not been so good a customer of ours for Seeds during the past twelve months as you used to be; and the more we looked at that record the more we wondered what we had done that caused you to practically stop dealing with us.

Finally we decided to drop you a line and ask you whether you will kindly tell us, personally, frankly, whether there is anything we have not done that we should have done.

Unfortunately accidents will happen at times, and if one has happened in this case we hope you will tell us about it so that we can try to put it right the day we get your letter. It does not make any difference what the trouble is, we will do our best to make it good.

Your faithful and obedient Servants,

Goodenough & Sons.

To Messrs. Goodenough & Sons.

Dear Sirs,—I regret to say there is a reason for discontinuing my seed order, and I am pleased to hear you will do your best to make the trouble good; but I am half afraid you will not be able to "put it right the day you get my letter."

The fact is there is a European War going on just now, and it has sadly upset our gardening plans. Instead of having eight men (counting a husband) about the place, I am now reduced to one gardener, and he will shortly be called up in a married group, unless the flat foot he is assiduously cultivating softens the heart of the Exemption Tribunal.

I am sorry I have no time to tell you more about this War, but I must now go and dig the vegetables.

Yours faithfully,

Helena Cressingham.

"Stabbing Affray due to a Girl's Charm.

In the village of Sharwida, Zagazig district, lives a girl who is a paragraph of beauty."

Egyptian Mail.

This barely does her justice. She seems to have been quite the penny novelette.

"In the Argonne we carried out a coup domain this morning."—Evening Paper.

It is a good General who never puts off till to-morrow what he can do this morning.

VI.—Chalk Farm.

Certain farmers farm in fruit, and some farm in grain,

Others farm in dairy-stuff, and many farm in vain,

But I know a place for a Sunday morning's walk

Where the Farmer and his Family only farm in Chalk.

The Farmer and his Family before you walk back

Will bid you in to sit awhile and share their midday snack;

O they that live in Chalk Farm they live at their ease,

For the Farmer and his Family can't tell Chalk from Cheese.

VII.—The Spaniards.

Three Spaniards dwell on Hampstead Heath:

One has a scowl and a knife in a sheath;

One twangs a guitar in the bright moonlight;

One chases a bull round a bush all night!

"In talking of flying, Boillot only returned to a pastime that he had been one of the first to practise."—Pall Mall Gazette.

Just like our Mr. Billing.

Miss Pandora (Heinemann) is proclaimed by its publishers to be a first novel. Probably, however, it will not also be a last, as the author, M. E. Norman, has a considerable gift for tale-telling. Perhaps I may be permitted to hope that he (or she) will use it next time to illuminate a rather more attractive set of characters. I don't think that the circle in which Pandora moved contains a single person whom I should wish to meet twice. There was Pandora herself, who was dark and Spanish-looking, with an origin wrapped in mild mystery. There was her friend, a futile lady-novelist; there were three quite disagreeable men, a spoilt child and an old lady suffering from senile dementia. Oh, and I nearly forgot the sniffy neighbour, who, having cut Pandora dead for half the book, was revealed in the second half as her mother. Add to this that Pandora had a past (and a present too, for that matter) with the husband of the lady novelist, and you will, I think, agree with me that they were a queer lot. Also I have seldom read a novel with such an unsatisfactory ending. It almost seemed as though M. E. Norman, having got the affair into a tangle, was too bored to unravel it. I am by no means sure, for example, that he (or she) had any clearer ideas about Pandora's paternity than I have. The depressing conclusion is that, while I readily admit that the writing of it shows originality and promise, Miss Pandora is hardly the novel I should have expected to be produced in a paper famine.

Before I began to unweave The Web of Fräulein (Hodder and Stoughton) a dreadful and, as it turned out, an unnecessary fear seized me that Miss Katharine Tynan had written a spy-novel of the present day. Imagine then my relief when I found that the story dates back some thirty or forty years, and that, although Fräulein was really as pestilential a woman as ever became governess to a respectable British family, espionage was not part of her game. With uncanny skill Miss Tynan relates the influence that this flat-footed German woman gained in the Allanson household; but I must protest, in justice to our race, that we have not many families so lacking in enterprise as to allow themselves to be enmeshed in such a web as this. In short I can dislike this German product very cordially but without for a moment understanding the source of the devastating power she had over others. You must not, however, imagine that the web casts a gloom over the whole book, for when Fräulein is not on the scene—and we do have some holidays from her—those Allansons whom she had not marked down could be attractively natural and gay; and the younger Allanson girl is as delightful a portrait as any in Miss Tynan's generous gallery.

I think I never met a writer who splashed language about with a greater recklessness than Miss Marion Hill. I see that one of the reviews of that previous best seller of hers, The Lure of Crooning Water, speaks of its literary charm. Well, there are, of course, many varieties of charm, but "literary" is hardly the epithet that I should myself apply to the undoubted attractions of A Slack Wire (Long). This very bustling story of the marriage between a variety artist and a quiet, not to say somewhat prigsome, young engineer is told for the most part in the purest American, an engaging and vivid medium with which I am but imperfectly acquainted. Further, Miss Hill's command of words seems to be gloriously unhampered by tradition. "It was with a supercargo of relief even heavier than usual that he found it" is a sample that I select at random. No, I certainly do not think that "literary" would be the epithet. But I am far from saying that there is no charm in the tale, of a sort. Not specially original perhaps the situation of the Bohemian wife brought to an ultra-Philistine home; but Miss Hill manages to keep it going briskly enough. And, as I have hinted, you never know what she will say next, or how. The whole thing would make such an admirable film-play that I can hardly believe this idea to have been absent from the intention of its author. The final sensation-scene, in which Violet uses her old wire-walking agility to prevent a catastrophe (never ask me how!), would make a fortune on the screen. Poor Violet, I may tell you, had been born in England, and, on the death of her rightful guardians, was "farmed off to peasants, who boarded her because it would cancel their poor-tax." I feel somehow that if I could grasp this reference it would make much in Violet clear. But so far it eludes me.

If powers of absorption are still left to you for any battles save those of to-day, you will find a vivid account of Flodden in The Crimson Field (Ward, Lock). I won't believe it is Mr. Halliwell Sutcliffe's fault that the fighting scenes of his story left me cold; the blame lies rather with the Hunnish times in which we live. While describing the beauty of the Yorkshire dales and the lives of their inhabitants, Mr. Sutcliffe held me in the hollow of his hand. But when he started to tell of the valiant deeds of the yeoman-hero, Sylvester Demain, who was knighted on the field of battle and won the maiden of high degree, I was released from that bondage. Indeed, I think Mr. Sutcliffe was no more anxious to leave the dales than I was, for, when the march to Flodden begins, his style becomes almost bewilderingly jumpy, so often does he look over his shoulder to see—and let us know—what is happening to those who were left behind. The fight, however, when it does come, is strenuous enough, and in the midst of it King James—German papers please copy—stands out as a pattern of chivalry.

A Dickens Revival.

"Wanted—Fat Boy for yard: 10s. weekly."

Dublin "Daily Independent."

Eighteen tailors from Leeds have been arrested at Dublin as deserters from the Army. As nine tailors make a man this is a net gain of two recruits.

Transcriber's Note: A linked Table of Contents has been provided for the convenience of the reader.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or The London Charivari, Vol.

150, April 19, 1916, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, CHARIVARI, APR 19, 1916 ***

***** This file should be named 36981-h.htm or 36981-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/6/9/8/36981/

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David Garcia and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.net),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the