The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 9, Slice 8, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 9, Slice 8

"Ethiopia" to "Evangelical Association"

Author: Various

Release Date: March 3, 2011 [EBook #35473]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOL 9 SL 8 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

Transcriber’s note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version.

Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will

be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online.

|

THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME IX SLICE VIII

Ethiopia to Evangelical Association

Articles in This Slice

| ETHIOPIA | EUONYMUS |

| ETHNOLOGY and ETHNOGRAPHY | EUPALINUS |

| ETHYL | EUPATORIA |

| ETHYL CHLORIDE | EUPATRIDAE |

| ETHYLENE | EUPEN |

| ÉTIENNE, CHARLES GUILLAUME | EUPHEMISM |

| ETIQUETTE | EUPHONIUM |

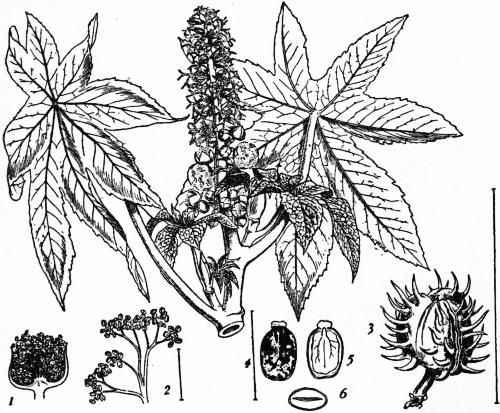

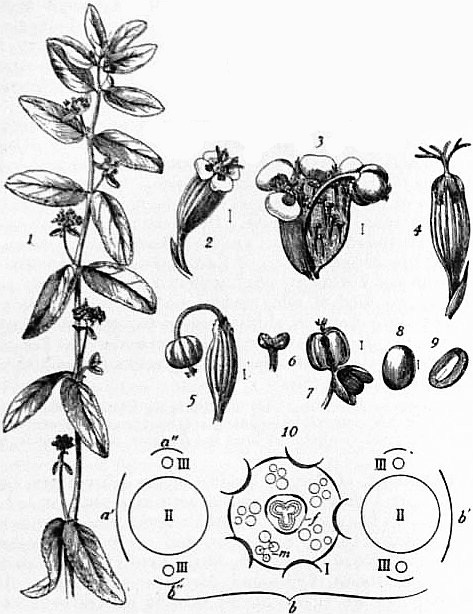

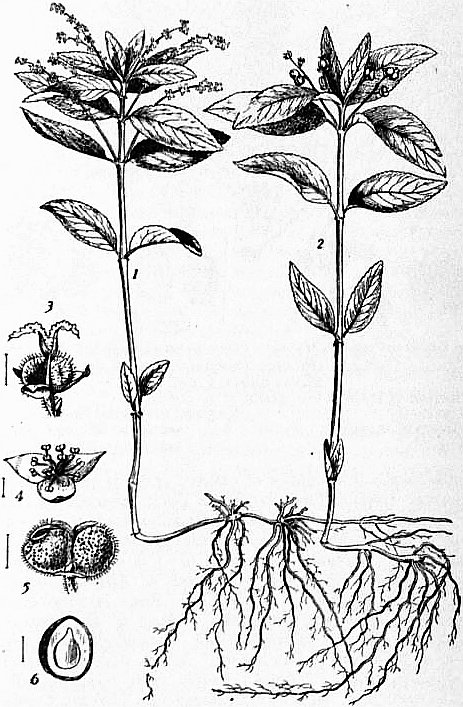

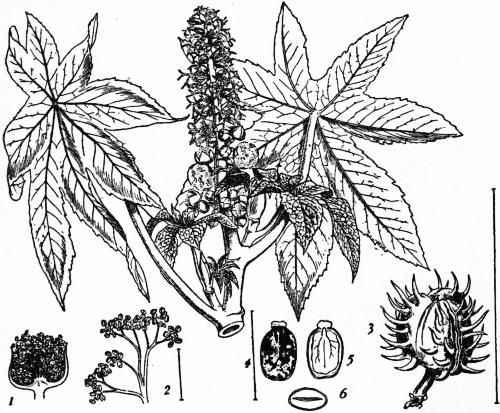

| ETNA (volcano) | EUPHORBIA |

| ETNA (Pennsylvania, U.S.A.) | EUPHORBIACEAE |

| ETON | EUPHORBIUM |

| ÉTRETAT | EUPHORBUS |

| ETRURIA | EUPHORION |

| ETTENHEIM | EUPHRANOR |

| ETTINGSHAUSEN, CONSTANTIN | EUPHRATES |

| ETTLINGEN | EUPHRONIUS |

| ETTMÜLLER, ERNST MORITZ LUDWIG | EUPHROSYNE |

| ETTMÜLLER, MICHAEL | EUPHUISM |

| ETTRICK | EUPION |

| ETTY, WILLIAM | EUPOLIS |

| ETYMOLOGY | EUPOMPUS |

| EU | EURASIAN |

| EUBOEA | EURE |

| EUBULIDES | EURE-ET-LOIR |

| EUBULUS (of Anaphlystus) | EUREKA |

| EUBULUS (Athenian poet) | EUREKA SPRINGS |

| EUCALYPTUS | EURIPIDES |

| EUCHARIS | EUROCLYDON |

| EUCHARIST | EUROPA |

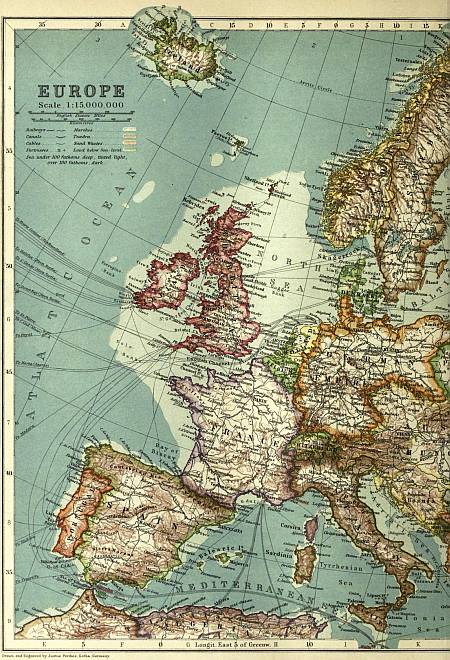

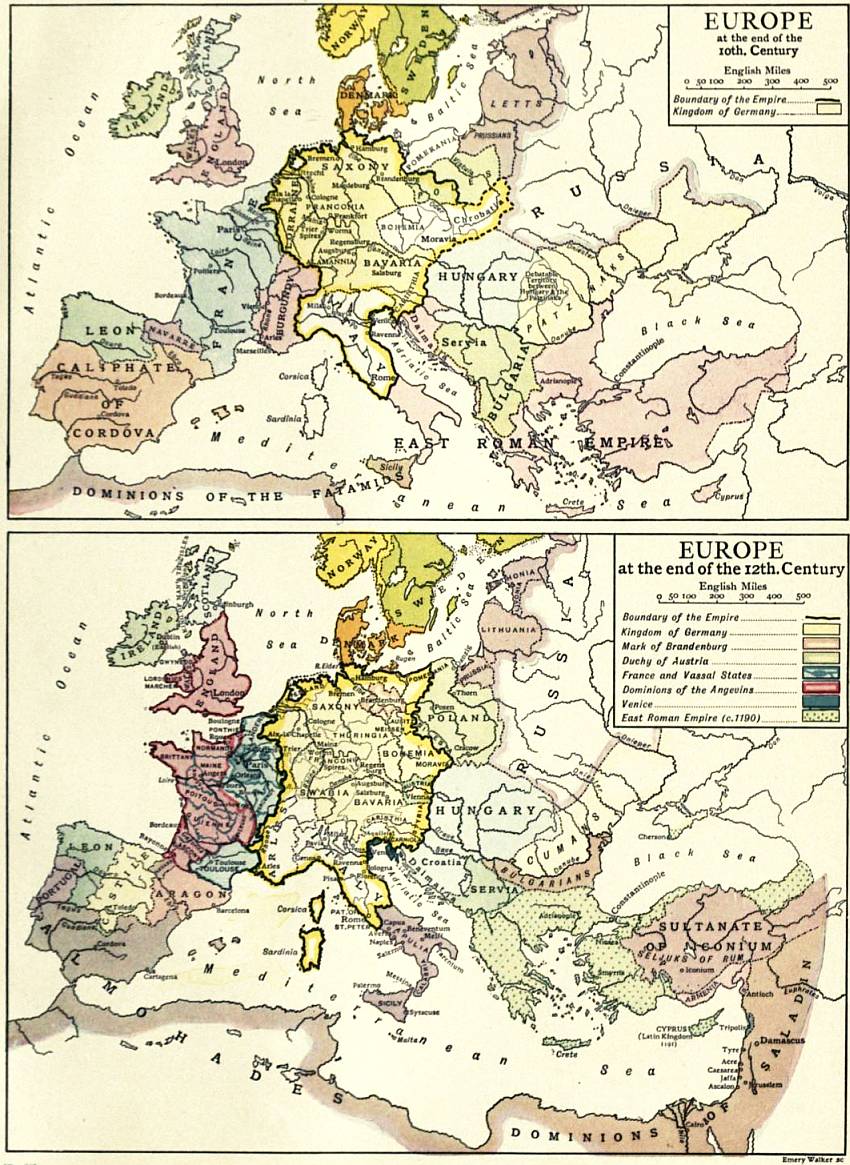

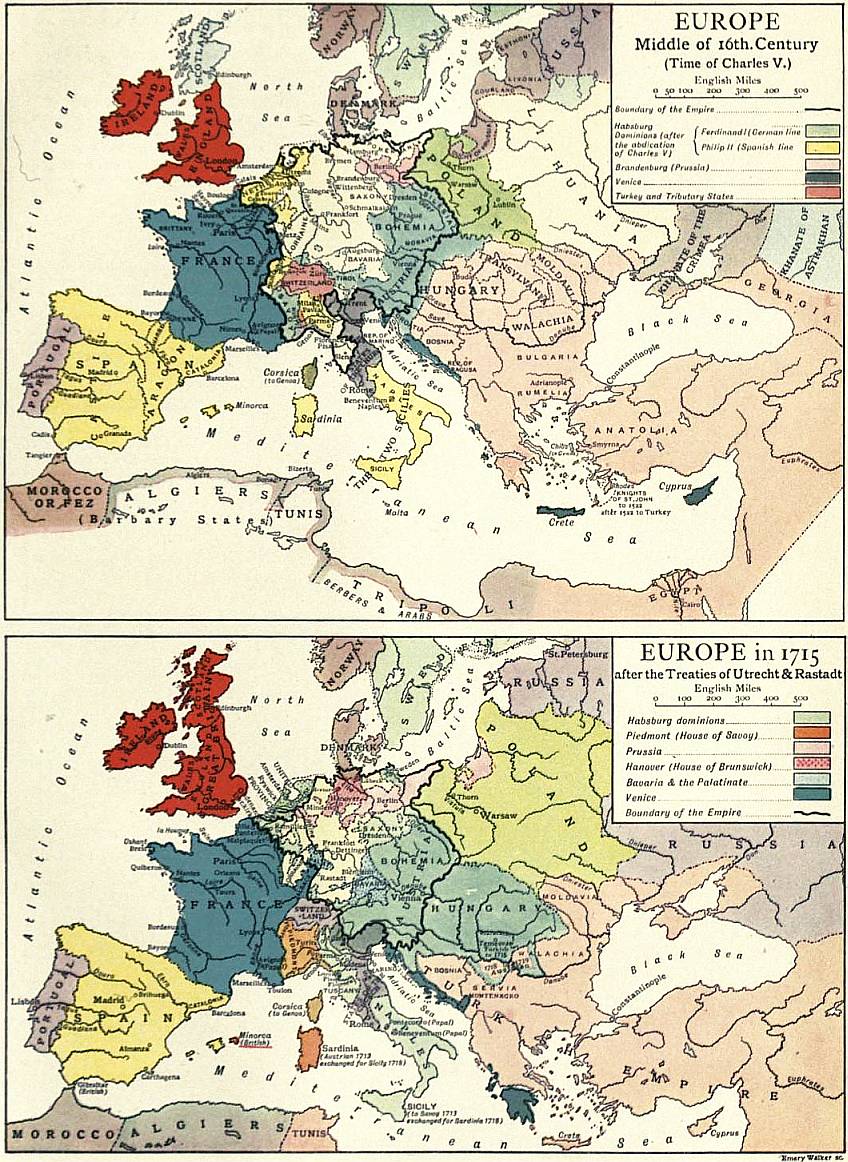

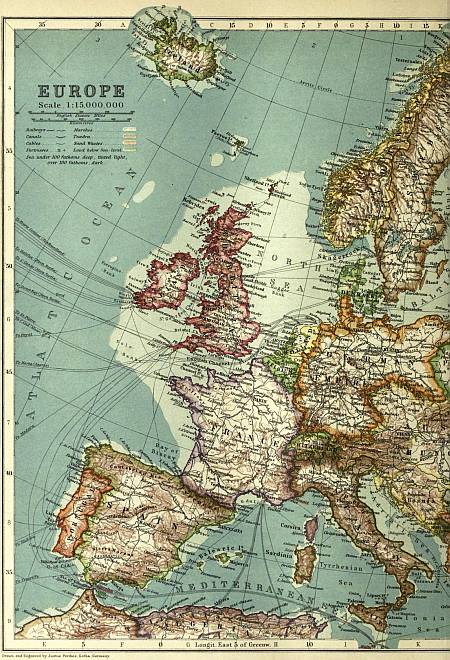

| EUCHRE | EUROPE |

| EUCKEN, RUDOLF CHRISTOPH | EUROPIUM |

| EUCLASE | EURYDICE |

| EUCLID (of Megara) | EURYMEDON |

| EUCLID (Greek mathematician) | EUSDEN, LAURENCE |

| EUCRATIDES | EUSEBIUS (many bishops) |

| EUDAEMONISM | EUSEBIUS (bishop of Rome) |

| EUDOCIA AUGUSTA | EUSEBIUS (of Caesarea) |

| EUDOCIA MACREMBOLITISSA | EUSEBIUS (of Emesa) |

| EUDOXIA LOPUKHINA | EUSEBIUS (of Myndus) |

| EUDOXUS (of Cnidus) | EUSEBIUS (of Nicomedia) |

| EUDOXUS (of Cyzicus) | EUSKIRCHEN |

| EUGENE OF SAVOY | EUSTACE |

| EUGENE | EUSTATHIUS (of Antioch) |

| EUGENICS | EUSTATHIUS (Macrembolites) |

| EUGÉNIE | EUSTATHIUS (of Thessalonica) |

| EUGENIUS | EUSTYLE |

| EUGENOL | EUTAWVILLE |

| EUHEMERUS | EUTHYDEMUS |

| EULENSPIEGEL, TILL | EUTIN |

| EULER, LEONHARD | EUTROPIUS |

| EUMENES (rulers of Pergamum) | EUTYCHES |

| EUMENES (Macedonian general) | EUTYCHIANUS |

| EUMENIDES | EUTYCHIDES |

| EUMENIUS | EUYUK |

| EUMOLPUS | EVAGORAS |

| EUNAPIUS | EVAGRIUS |

| EUNOMIUS | EVANDER |

| EUNUCH | EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE |

| EUNUCH FLUTE | EVANGELICAL ASSOCIATION |

845

ETHIOPIA, or Aethiopia (Gr. Αἰθιοπία), the ancient classical

name of a district of north-eastern Africa, bounded on the N. by

Egypt and on the E. by the Red Sea.1 The application of the

name has varied considerably at different times. In the Homeric

poems the Aethiopes are the furthest of mankind both eastward

and westward; the gods go to their banquets and probably the

Sun sets in their country. With the growth of scientific geography

they came to be located somewhat less vaguely, and

indeed their name was employed as the equivalent of the Assyrian

and Hebrew Cush (q.v.), the Kesh or Ekōsh of the Hieroglyphics

(first found in Stele of Senwosri I.), i.e. a country extending

from about the 24th to the 10th degree of N. lat., while its limits

to the E. and W. were doubtful. The etymology of the name,

which to a Greek ear meant “swarthy-faced,” is unknown, nor

can we say why in official inscriptions of the Axumite dynasty

the word is used as the equivalent of Habashat (whence the

846

modern Abyssinia), which, from the context would appear to

denote a tribe located in S. Arabia, whose name was rendered

by the Greek geographers as Abaseni and Abissa.

The inhabitants of Ethiopia, partly perhaps owing to their

honourable mention in the Homeric poems, attracted the attention

of many Greek researchers, from Democritus onwards.

Herodotus divides them into two main groups, a straight-haired

race and a woolly-haired race, dwelling respectively to the East

and West, and this distinction is confirmed by the Egyptian

monuments. From his time onwards various names of tribes are

enumerated, and to some extent geographically located, most of

these appellations being Greek words, applied to the tribes by

strangers in virtue of what seemed to be their leading characteristics,

e.g. “Long-lived,” “Fish-eaters,” “Troglodytes,” &c.

The bulk of our information is derived from Egyptian monuments,

whence it appears that, originally occupied by independent

tribes, who were raided (first by Seneferu or Snefru, first king of

the IVth or last of the IIIrd Dynasty) and gradually subjected

by Egyptian kings (the steps in this process are traced by E.W.

Budge, The Egyptian Sudan, 1907, i. 505 sqq.), under the XVIIIth

Dynasty it became an Egyptian province, administered by a

viceroy (at first the Egyptian king’s son), called prince of Kesh,

and paying tributes in negroes, oxen, gold, ivory, rare beads,

hides and household utensils. The inhabitants frequently

rebelled and were as often subdued; records of these repeated

conquests were set up by the Egyptian kings in the shape of

steles and temples; of the latter the temple of Amenhotep

(Amenophis) III. at Soleb or Sulb seems to have been the most

magnificent. Ethiopia became independent towards the 11th

century B.C., when the XXIst Dynasty was reigning in Egypt.

A state was founded, having for its capital Napata (mod. Merawi)

at the foot of Jebel Barkal, “the sacred mountain,” which in

time became formidable, and in the middle of the 8th century

conquered Egypt; an Egyptian campaign is recorded in the

famous stele of King Pankhi. The fortunes of the Ethiopian

(XXVth) Dynasty belong to the history of Egypt (q.v.). After

the Ethiopian yoke had been shaken off by Egypt, about 660 B.C.,

Ethiopia continued independent, under kings of whom not a few

are known from inscriptions. Besides a number whose names

have been discovered in cartouches at Jebel Barkal, the following,

of whom all but the third have left important steles, can be

roughly dated: Tandamane, son of Tirhaka (667-650), Asperta

(630-600), Pankharer (600-560), Harsiōtf (560-525), Nastasen

(525-500). From the evidence of the stele of the second (the

Coronation Stele) and that of the fifth it has been inferred that

the sovereignty early in this period became elective, a deputation

of the various orders in the realm being (as Diodorus states),

when a vacancy occurred, sent to Napata, where the chief god

Amen selected out of the members of the royal family the person

who was to succeed, and who became officially the god’s son;

and it seems certain that the priestly caste was more influential

in Ethiopia than in Egypt both before and after this period.

Another stele (called the Stele of Excommunication) records

the expulsion of a priestly family guilty of murder (H. Schäfer,

Klio, vi. 287): the name of the sovereign who expelled them has

been obliterated. The stele of Harsiōtf contains the record of

nine expeditions, in the course of which the king subdued various

tribes south of Meroë and built a number of temples. The stele of

the last of these sovereigns, now in the Berlin Museum, and edited

by H. Schäfer (Leipzig, 1901), contains valuable information concerning

the state of the Ethiopian kingdom in its author’s time.

Shortly after his accession he was threatened with invasion by

Cambyses, the Persian conqueror of Egypt, but (according to his

own account) destroyed the fleet sent by the invader up the Nile,

while (as we learn from Herodotus) the land-force succumbed

to famine (see Cambyses). It further appears that in his time

and that of his immediate predecessors the capital of the kingdom

had been removed from Napata, where in the time of Harsiōtf

the temples and palaces were already in ruins, to Mercë at a

distance of 60 camel-hours to the south-east. But Napata

retained its importance as the religious metropolis; it was thither

that the king went to be crowned, and there too the chief god

delivered his oracles, which were (it is said) implicitly obeyed.

The local names in Nastasen’s inscription, describing his royal

circuit, are in many cases obscure. A city named Pnups (Hierogl.

Pa-Nebes) appears to have constituted the most northerly point

in the empire. These Ethiopian kings seem to have made no

attempt to reconquer Egypt, though they were often engaged

in wars with the wild tribes of the Sudan. For the 5th and 4th

centuries B.C. the history of the country is a blank. A fresh

epoch was, however, inaugurated by Ergamenes, a contemporary

of Ptolemy Philadelphus, who is said to have massacred the

priests at Napata, and destroyed sacerdotal influence, till then

so great that the king might at the priests’ order be compelled

to destroy himself; Diodorus attributes this measure to Ergamenes’

acquaintance with Greek culture, which he introduced

into his country. A temple was built by this king at Pselcis

(Dakka) to Thoth. Probably the sovereignty again became

hereditary. Occasional notices of Ethiopia occur from this time

onwards in Greek and Latin authors, though the special treatises

by Agatharchides and others are lost. According to these the

country came to be ruled by queens named Candace. One of

them was involved in war with the Romans in 24 and 23 B.C.;

the land was invaded by C. Petronius, who took the fortress

Premis or Ibrim, and sacked the capital (then Napata); the

emperor Augustus, however, ordered the evacuation of the

country without even demanding tribute. The stretch of land

between Assuan (Syene) and Maharraka (Hiera Sycaminus) was,

however, regarded as belonging to the Roman empire, and Roman

cohorts were stationed at the latter place. To judge by the

monuments it is possible that there were queens who reigned

alone. Pyramids were erected for queens as well as for kings,

and the position of the queens was little inferior to that of their

consorts, though, so far as monumental representations go, they

always yielded precedence to the latter. Candace appears to

be found as the name of a queen for whom a pyramid was built

at Meroë. A great builder was Netekamane, who is represented

with his queen Amanetari on temples of Egyptian style at many

points up the Nile—at Amara just above the second cataract,

and at Napata, as well as at Meroë, Benaga and Naga in the

distant Isle of Meroë. He belongs, probably, to the Ptolemaic

age. Later, in the Roman period, the type in sculpture changed

from the Egyptian. The figures are obese, especially the women,

and have pronounced negro features, and the royal person is

loaded with bulging gold ornaments. Of this period also there

is a royal pair, Netekamane and Amanetari, imitating the names

of their conspicuous predecessors. In the 4th century A.D. the

state of Meroë was ravaged by the Nubas(?) and the Abyssinians,

and in the 6th century its place was taken by the Christian state

of Nubia (see Dongola).

Contrary to the opinion of the Greeks, the Ethiopians appear

to have derived their religion and civilization from the Egyptians.

The royal inscriptions are written in the hieroglyphic character

and the Egyptian language, which, however, in the opinion of

experts, steadily deteriorate after the separation of Ethiopia

from Egypt. About the time of Ergamenes, or (according to

some authorities) before, a vernacular came to be employed in

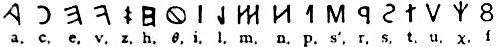

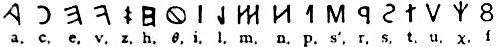

inscriptions, written in a special alphabet of 23 signs in parallel

hieroglyphic and cursive forms. The cursive is to be read from

right to left, the hieroglyphic, contrary to the Egyptian method,

in the direction in which the figures face. The Egyptian equivalents

of six characters have been made out by the aid of bilingual

cartouches. Words are divided from each other by pairs of dots,

and it is clear that the forms and values of the signs are largely

based on Egyptian writing; but as yet decipherment has not

been attained, nor can it yet be stated to what group the

language should be assigned (F. Ll. Griffith in D.R. MacIver’s

Areika, Oxford, 1909, and later researches).

Notices in Greek authors are collected by P. Paulitschke, Die

geographische Erforschung des afrikanischen Continents (Vienna,

1880); the inscriptions were edited and interpreted by G. Maspero,

Revue archéol. xxii., xxv.; Mélanges d’Assyriologie et d’Égyptologie,

ii., iii.; Records of the Past, vi.; T.S.B.A. iv.; Schäfer, l.c., and Zeitschrift

für ägyptische Sprache, xxxiii. See also J.H. Breasted, “The

Monuments of Sudanese Nubia,” in American Journal of Semitic

847

Languages (October 1908), and the work of E.W. Budge cited above.

A description of the chief ruins and the results of Dr D.R. MacIver’s

researches in northern Nubia, begun in 1907, will be found under

Sudan: Anglo-Egyptian.

The Axumite Kingdom.—About the 1st century of the Christian

era a new kingdom grew up at Axum (q.v.), of which a king

Zoscales is mentioned in the Periplus Maris Erythraei. Fragments

of the history of this kingdom, of which there is no

authentic chronicle, have been made out chiefly by the aid of

inscriptions, of which the following is a list:—(1) Greek inscription

of Adulis, copied by Cosmas Indicopleustes in 545,

the beginning, with the king’s name, lost. (2) Sabaean inscription

of Ela Amida in two halves, discovered by J. Theodore Bent

at Axum in 1893, and completed by E. Littmann in 1906. (3)

Ethiopic inscription probably of the same king, imperfect

(Littmann). (4) Trilingual inscription of Aeizanes, the Greek

version discovered by Henry Salt in 1805, the Sabaean by Bent,

and the Ethiopic (Geez) by Littmann. (5) Ethiopic inscription

of Aeizanes (so Littmann), son of Ela Amida, discovered by

Eduard Rüppell in 1833. (6) Ethiopic inscriptions of Hetana-Dan’el,

son of Dabra Efrem. These are all long inscriptions

giving details of wars, &c. The sixth is later than the rest,

which are to be attributed to the most flourishing period of

the kingdom, the 4th and 5th centuries A.D. The fourth is pagan,

the fifth Christian, Aeizanes having in the interval embraced

Christianity. It was to this king that the emperor Constantius

addressed a letter in 356 A.D.

Aeizanes and his successors style themselves kings of the

Axumites, Homerites (Himyar), Raidan, the Ethiopians

(Habašat), the Sabaeans, Silee, Tiamo, the Bugaites (Beģa) and

Kasu. This style implies considerable conquests in South

Arabia, which, however, must have been lost to the Axumites

by A.D. 378. They claim to rule the Kasu or Meroitic Ethiopians;

and the fifth inscription records an expedition along the Atbara

and the Nile to punish the Nuba and Kasu, and a fragment of a

Greek inscription from Meroë was recognized by Sayce as

commemorating a king of Axum. Except for these inscriptions

Axumite history is a blank until in the 6th century we find

the Axumite king sending an expedition to wreck the Jewish

state then existing in S. Arabia, and reducing that country

to a state of vassalage: the king is styled in Ethiopian

chronicles Caleb (Kaleb), in Greek and Arabic documents

El-Esbaha. In the 7th century a successor to this king,

named Abraha or Abraham, gave refuge to the persecuted

followers of Mahomet at the beginning of his career (see Arabia:

History, ad init.). A few more names of kings occur on coins,

which were struck in Greek characters till about A.D. 700, after

which time that language seems definitely to have been displaced

in favour of Ethiopic or Geez: the condition of the script and

the coins renders them all difficult to identify with the names

preserved in the native lists, which are too fanciful and mutually

contradictory to furnish of themselves even a vestige of history.

For the period between the rise of Islam and the beginning of

the modern history of Abyssinia there are a few notices in Arabic

writers; so we have a notice of a war between Ethiopia and

Nubia about 687 (C.C. Rossini in Giorn. Soc. Asiat. Ital. x. 141),

and of a letter to George king of Nubia from the king of Abyssinia

some time between 978 and 1003, when a Jewish queen Judith was

oppressing the Christian population (I. Guidi, ibid. iii. 176, 7).

The Abyssinian chronicles, it may be noted, attribute the

foundation of the kingdom to Menelek (or Ibn el-Hakim), son of

Solomon and the queen of Sheba. The Axumite or Menelek

dynasty was driven from northern Abyssinia by Judith, but soon

after another Christian dynasty, that of the Zagués, obtained

power. In 1268 the reigning prince abdicated in favour of

Yekūnō Amlāk. king of Shoa, a descendant of the monarch overthrown

by Judith (see Abyssinia).

See A. Dillman, Die Anfänge des axumitischen Reiches (Berlin,

1879); E. Drouin, Revue archéol. xliv. (1882); T. Mommsen,

Geschichte der römischen Provinzen, chap. xiii.; W. Dittenberger,

Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones selectae, Nos. 199, 200; Littmann u.

Kroncker, Vorbericht der deutschen Aksum-Expedition (Berlin, 1906),

and Littman’s subsequent researches.

Ethiopic Literature

The employment of the Geez or Ethiopic language for literary

purposes appears to have begun no long time before the introduction

of Christianity into Abyssinia, and its pagan period is

represented by two Axumite inscriptions (published by D.H.

Müller in J.T. Bent’s Sacred City of the Ethiopians, 1893), and

an inscription at Matara (published by C.C. Rossini, Rendiconti

Accad. Lincei, 1896). As a literary language it survived its

use as a vernacular, but it is unknown at what time it ceased to

be the latter. In Sir W. Cornwallis Harris’s Highlands of

Aethiopia (1844) there is a list of rather more than 100 works

extant in Ethiopic; subsequent research has chiefly brought to

light fresh copies of the same works, but it has contributed some

fresh titles. A conspectus of all the MSS. known to exist in

Europe (over 1200 in number) was published by C.C. Rossini

in 1899 (Rendiconti Accad. Lincei, ser. v. vol. viii.); of these

the largest collection is that in the British Museum, but others

of various sizes are to be found in the chief libraries of Europe.

R.E. Littmann (in the Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, xv. and xvi.)

describes two collections at Jerusalem, one of which contains

283 MSS.; and Rossini (Rendiconti, 1904) a collection of 35 MSS.

belonging to the Catholic mission at Cheren. Other collections

exist in Abyssinia, and many MSS. are in private hands. In

1893 besides portions of the Bible some 40 Ethiopic books had

been printed in Europe (enumerated in L. Goldschmidt’s Bibliotheca

Aethiopica), but many more have since been published.

Geez literature is ordinarily divided into two periods, of

which the first dates from the establishment of Christianity

in the 5th century, and ends somewhere in the 7th; the

second from the re-establishment of the Salomonic dynasty in

1268, continuing to the present time. It consists chiefly of

translations, made in the first period from Greek, in the second

from Arabic. It has no authors of the first or even of the second

rank. Its character as a sacred and literary language is due to

its translation of the Bible, which in the ordinary enumeration

is made to contain 81 books, 46 of the Old Testament, and 35

of the New. These figures are most probably obtained by adding

to the ordinary canonical books Maccabees, Tobit, Judith,

Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, Jubilees, Enoch, the Ascension

of Isaiah, Ezra IV., Shepherd of Hermas, the Synodos (Canons of

the Apostles), the Book of Adam, and Joseph Ben Gorion. For

the distinction between canonical and apocryphal appears to be

unknown to the Ethiopic Church, whose chief service to Biblical

literature consists in its preservation of various apocryphal

works which other parts of Christendom have lost or possess

only in an imperfect form (see Enoch; Jubilees, Book of, &c.).

It should be observed that the Maccabees of the Ethiopic Bible

is an entirely different work from the books of that name included

in the Septuagint, of which, however, the Abyssinians have a

recent version made from the Vulgate; specimens of their

own Maccabees have been published by J. Horovitz in the

Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, vol. xx. The MSS. of the Biblical

books vary very much, and none of them can claim any great

antiquity; the oldest extant MS. of the four Books of Kings

appears to be one in the Museo Borgiano, presented by King

Amda Sion (1314) to the Virgin Mary in Jerusalem (described

by N. Roupp, ibid. xvi. 296-342). Hence P. de Lagarde supposed

the Ethiopic version to have been made from the Arabic, which

indeed is in accordance with a native tradition. This opinion

is held by few; C.F.A. Dillman distinguished in the case of

the Old Testament three classes of MSS., a versio antiqua, made

from the Septuagint (probably in the Hesychian text), a class

revised from Greek MSS., and a class revised from the Hebrew

(probably through the medium of an Arabic version). An

examination of ten chapters of St Matthew by L. Hackspill

(ibid. vol. xi.) led to the result that the Ethiopic version of the

Gospels was made about A.D. 500, from a Syro-occidental text,

and that this original translation is represented by Cod. Paris.

Aeth. 32; whereas most MSS. and all printed editions contain a

text influenced by the Alexandrian Vulgate, and show traces

of Arabic. Rossini (ibid. x. 232) has made it probable that the

848

Abba Salāmā, whom the native tradition identifies with Frumentius,

evangelist of Abyssinia, to whom the translation of the

Bible was ascribed, was in reality a Metropolitan of the early

14th century, who revised the corrupt text then current. Of

the ancient translation the latest book is said to be Ecclesiasticus,

translated in the year 678. The New Testament has been

published repeatedly (first in Rome, 1548-1549; some letters

about its publication were edited by I. Guidi in the Archivio della

Soc. Rom. di Storia Patria, 1886), and C.F.A. Dillmann edited

a critical text of most of the Old Testament and Apocrypha,

but did not live to complete it; portions have been edited by

J. Bachmann and others.

Other translations thought to belong to the first period are

the Sher‘ata Makhbār, ascribed to S. Pachomius; the Kerilos,

a collection of homilies and tracts, beginning with Cyril of

Alexandria De recta fide; and the Physiologus, a fanciful work

on Natural History (edited by F. Hommel, Leipzig, 1877).

Of the works belonging to the second period much the most

important are those which deal with Abyssinian history. A

court official, called sahāfē te’ezāzenet (secretary), having under

him a staff of scribes, was employed to draw up the public annals

year by year; and on these official compositions the Abyssinian

histories are based. The earliest part of the Axum chronicle

preserved is that recording the wars of Amda Sion (1314-1344)

against the Moslems; it is doubtful, however, whether even

this exists in its original form, as some scholars think; according

to its editor (J. Perruchon in the Journ. Asiat. for 1889) it is

preserved in a recension of the time of King Zar‘a Ya‘kūb. Under

King Lebna Dengel (1508-1540) the annals of his four predecessors,

Zar‘a Ya‘kūb, Baeda Maryam, Eskender and Na‘od

(1434-1508) were drawn up; those of the first two were published

by J. Perruchon (Paris, 1893); in the Journ. Asiat. for 1894

the same scholar published a further fragment of the history

of Baeda Maryam, written by the tutor to the king’s children,

and the history of Eskender, Amda Sion II. and Na’od as compiled

in Lebna Dengel’s time. The history of Lebna Dengel was

published by the same scholar (Journ. Semit. i. 274) and Rossini

(Rendiconti, 1894, v. p. 617); that of his successor Claudius

(1540-1559) by Conzelmann (Paris, 1895); that of his successor

Minas (1559-1563) by F.M.E. Pereira (Lisbon, 1888); those

of the three following kings, Sharsa Dengel, Zā Dengel, and

Ya’kūb, by Rossini (Rendiconti, 1893). The history of the next

king Sysenius (1606-1632) by Abba Meherka Dengel and Tekla

Shelase was edited by Pereira (Lisbon, 1892); the chronicles

of Joannes I., Iyasu I. and Bakaffa (1682-1730) by I. Guidi,

with a French translation (Paris, 1903-1905); all are contemporary,

and the names of the chroniclers of the last two

kings are recorded. Besides these we have the partly fabulous

chronicle of Lalibela (of uncertain date, but before the Salomonian

dynasty was restored), edited by Perruchon (Paris,

1892); and a brief chronicle of Abyssinia, drawn up in the reign

of Iyasu II. (1729-1753), embodying materials abridged, but

often unaltered, was published by R. Basset, in the Journ.

Asiat. for 1882 (cf. Rossini in the Rendiconti, 1893-1894, p. 668),

and has since formed the basis for Abyssinian history. Many

compilations of the sort exist in MS. in libraries, and great praise

is bestowed on the one which E. Rüppell, when travelling in

Abyssinia, ordered to be drawn up for his use. It is now in the

collection of his MSS. at Frankfurt. Ethiopic scholars speak of a

special “historical style” which comes from the mixture of the

styles of different periods, and the admixture of Amharic phrases

and idioms. The historian of the wars of Amda Sion is credited

with some literary merit; most of the chroniclers have little.

The remaining literature of the second period is thought to

begin somewhat earlier than these chronicles. To the time of

King Yekūnō Amlāk (1268-1283) the historical romance called

Kebra Nagaset (Glory of Kings) is assigned by its editor, C.

Bezold (Bavarian Academy, 1904); other scholars gave it a

somewhat later date. Its purpose is to glorify the Salomonian

dynasty, whence, in spite of a colophon which declares it to be

a translation, it was regarded as an original work; since, however,

it shows evident signs of having been translated from Arabic,

Bezold supposes that its author, Ishāk, was an immigrant whose

native language was Arabic, in which therefore he would naturally

write the first draft of his book. To the time of Yagbea Sion

(ob. 1294) belongs the Vision of the Prophet Habakkuk in Kartasā,

as also the works of Abba Salāmā, regarded as the founder of the

Ethiopic renaissance, one of whose sermons is preserved in a

Cheren MS. With his name are connected the Acts of the Passion,

the Service for the Dead and the translation of Philexius, i.e.

Philoxenus. King Zar‘a Ya‘kūb composed or had composed for

him as many as seven books; the most important of these is the

Book of Light (Mashafa Berhān), paraphrased as Kirchenordnung,

by Dillmann, who gave an analysis of its contents (Über die

Regierung des Königs Zar‘a Ya‘kob, Berl. Acad., 1884). He also

organized the compilation of the Miracles of the Virgin Mary,

one of the most popular of Ethiopic books; a magnificent edition

was printed by E.W. Budge in the Meux collection (London,

1900). In the same reign the Arabic chronicle of al-Makīn was

translated into Geez. Under Lebna Dengel (ob. 1540), besides

the above-mentioned collection of chronicles, we hear of the

translation from the Arabic of the history and martyrdom of

St George, the Commentary of J. Chrysostom on the Epistle

to the Hebrews, and the ascetic works of J. Saba called Aragāwī

manfasāwī. Under Claudius (1540-1559) Maba Sion is said to

have translated from the Arabic The Faith of the Fathers, a vast

compilation, including the Didascalia Apostalorum (edited by

Platt, London, 1834), and the Creed of Jacob Baradaeus (published

by Cornill, ZDMG. xxx. 417-466), and to the same reign

belong the Book of Extreme Unction (Mashafa Kandīl), and the

religious romance Barlaam et Joasaph also paraphrased from

the Arabic (partly edited by A. Zotenberg in Notices et Extraits,

vol. xxviii.). The Confession of Faith of King Claudius has been

repeatedly printed. The reign of Sharsa Dengel (ob. 1595) was

marked by many literary monuments, such as the religious and

controversial compilation called Mazmura Chrestos, and the

translation, by a certain Salik, of the religious encyclopaedia

(Mashafa Hāiā) of the monk Nikon; an Arab merchant from

Yemen, who took on conversion the name Anbākōm (Habakkuk),

translated a number of books from the Arabic. Under Ya’kūb

(ob. 1605) the valuable chronicle of John of Nikiou was translated

from Arabic (edited by A. Zotenberg with French translation in

Notices et extraits, vol. xxiv.). Under John, about 1687, the

Spiritual Medicine of Michael, bishop of Adtrib and Malig, was

translated. The literature that is not accurately dated consists

largely of liturgies, prayers and hymns; Ethiopic poetry is

chiefly, if not entirely, represented by the last of these, the most

popular work of the kind being an ode in praise of the Virgin,

called Weddase Maryam (edited by K. Fries, Leipzig, 1892).

Various hymn-books bear the names Degua, Zemmare and

Mawas‘et (Antiphones); there is also a biblical history in verse

called Mashafa Madbal or Mestīra Zamān. Homilies also exist

in large numbers, both original and translated, sometimes after

the Arabic fashion in rhymed prose. Hagiology is naturally

an important department in Ethiopic literature. In the great

collection called Synaxar (translated originally from Arabic,

but with large additions) for each day of the year there is the

history of one or more saints; an attempt has been made by

H. Dünsing (1900) to derive some actual history from it. Many

texts containing lives of individual saints have been issued.

Such are those of Maba Sion and Gabra Chrestos, edited by Budge

in the Meux collection (London, 1899); the Acts of S. Mercurius,

of which a fragment was edited by Rossini (Rome, 1904); the

unique MS. of the original, one of the most extensive works in the

Geez language, was burned by thieves who set fire to the editor’s

house. The same scholar began a series of Vitae Sanctorum

antiquiorum, while Monumenta Aethiopiae hagiologica and Vitae

Sanctorum indigenarum have been edited by B. Turaiev (Leipzig

and St Petersburg, 1902, and Rome, 1905). Other lives have been

edited by Pereira, Guidi, &c. Similar in historical value to these

works is the History of the Exploits of Alexander, of which various

recensions have been edited by Budge (London, 1895). See

further Alexander the Great, section on the legends, ad fin.

Of Law the most important monument is the Fatha Nagaset

849

(Judgment of Kings), of which an official edition was issued by

I. Guidi (Rome, 1899), with an Italian translation; it is a version

probably made in the early 16th century of the Arabic code of

Ibn ‘Assal, of the 12th century, whose work, being meant for

Christians living under Moslem rule, was not altogether suitable

for an independent Christian kingdom; yet the need for such

a code made it popular and authoritative in Abyssinia. The

translator was not quite equal to his task, and the Brit. Mus.

MS. 800 exhibits an attempt to correct it from the original.

Science can scarcely be said to exist in Geez literature, unless a

medical treatise, of which the British Museum possesses a copy,

comes under this head. Philosophy is mainly represented by

mystical commentaries on Scripture, such as the Book of the

Mystery of Heaven and Earth, by Ba-Hailu Michael, probably of

the 15th century, edited by Perruchon and Guidi (Paris, 1903).

There is, however, a translation of the Book of the Wise Philosophers,

made by Michael, son of Abba Michael, consisting of

various aphorisms; specimens have been edited by Dillmann in

his Chrestomathy, and J. Cornill (Leipzig, 1876). There is also

a translation of Secundus the Silent, edited by Bachmann (Berlin,

1888). Far more interesting than these is the treatise of Zar‘a

Ya‘kūb of Axum, composed in the year 1660 (edited by Littman,

1904), which contains an endeavour to evolve rules of

life according to nature. The author reviews the codes of

Moses, the Gospel and the Koran, and decides that all contravene

the obvious intentions of the Creator. He also gives some

details of his own life and his occupation of scribe. A less

original treatise by Walda Haywat accompanies it. Epistolography

is represented by the diplomatic correspondence of some

of the kings with the Portuguese and Spanish courts; some

documents of this sort have been edited by C. Beccari, Documenti

inediti per la storia d’ Etiopia (Rome, 1903); lexicography, by

the vocabulary called Sawāsew. The first Ethiopic book printed

was the Psalter (Rome, 1513), by John Potken of Cologne, the

first European who studied the language.

See C.C. Rossini, “Note per la storia letteraria Abissina,” in

Rendiconti della R. Accad. dei Lincei (1899); Fumagalli, Bibliografia

Etiopica (1893); Basset, Études sur l’histoire de l’Éthiopie (1882);

Catalogues of various libraries, especially British Museum (Wright),

Paris (Zotenberg), Oxford and Berlin (Dillmann), Frankfurt (Goldschmidt).

Plates illustrating Ethiopic palaeography are to be found

in Wright’s Catalogue; an account of the illustrations in Ethiopic

MSS. is given by Budge in his Life of Maba Sion; and a collection

of inscriptions in the church of St Stefano dei Mori, in Rome, by

Gallina in the Archivio della Soc. Rom. di Storia Patria (1888).

(D. S. M.*)

ETHNOLOGY and ETHNOGRAPHY (from the Gr. ἔθνος, race,

and λόγος, science, or γράφειν, to write), sciences which in their

narrowest sense deal respectively with man as a racial unit

(mankind), i.e. his development through the family and tribal

stages into national life, and with the distribution over the earth

of the races and nations thus formed. Though the etymology of

the words permits in theory of this line of division between

ethnology and ethnography, in practice they form an indivisible

study of man’s progress from the point at which anthropology

(q.v.) leaves him.

Ethnology is thus the general name for investigations of the

widest character, including subjects which in this encyclopaedia

are dealt with in detail under separate headings, such as Archaeology,

Art (and allied articles), Commerce, Geography (and

the headings for countries and tribes), Family, Name, Ethics,

Law, Mythology, Folk-Lore (and allied articles), Philology

(and allied articles), Agriculture, Architecture, Religion,

Sociology, &c., &c. It covers generally the whole history of

the material and intellectual development of man, as it has

passed through the stages of (a) hunting and fishing, (b) sheep

and cattle tending, (c) agriculture, (d) industry. It investigates

his food, his weapons, tools and implements, his housing, his

social, economic and commercial organization, forms of government,

language, art, literature, morals, superstitions and religious

systems. In this sense ethnology is the older term for what now

is called sociology. At the present day the progress of research

has in practice, however, restricted the “ethnologist” as a

rule to the study of one or more branches only of so wide a

subject, and the word “ethnology” is used with a somewhat

vague meaning for any ethnological study; each country or

nation has thus its own separate ethnology. It becomes more

convenient, therefore, to deal with the ethnology as a special

subject in each case. “Ethnography,” in so far as it has a

distinctive province, is then conveniently restricted to the

scientific mapping out of different racial regions, nations and

tribes; and it is only necessary here to refer the reader to the

separate articles on continents, &c., where this is done. The

only fundamental problem which need here be referred to is

that of the whole question of the division of mankind into

separate races at all, which is consequential on the earlier problem

(dealt with in the article Anthropology) as to man’s origin and

antiquity.

If we assume that man existed on the earth in remote geological

time, the question arises, was this pleistocene man specifically

one? What evidence is there that he represented in his different

habitats a series of varieties of one species rather than a series

of species? The evidence is of three kinds, (1) anatomical,

(2) physiological, (3) cultural and psychical.

1. Dr Robert Munro, in his address to the Anthropological

section of the British Association in 1893, said: “All the

osseous remains of man which have hitherto been collected and

examined point to the fact that, during the larger portion of the

quarternary period, if not, indeed, from its very commencement,

he had already acquired his human characteristics.” By

“characteristics” is here meant those anatomical ones which

distinguish man from other animals, not the physical criteria of

the various races. Do, then, these anatomical characteristics

of pleistocene man show such differences among themselves and

between them and the types of man existing to-day as to justify

the assumption that there has ever been more than one species

of man?

The undoubted “osseous remains” of pleistocene man are

few. Burial was not practised, and the few bones found are for

the most part those which have by mere chance been preserved

in caves or rock-shelters. Of these the three chief “finds,”

in order of probable age, are the Trinil (Java) brain-cap, the lowest

human skull yet described, characterized by depressed cranial

arch, with a cephalic index of 70; the Neanderthal (Germany)

skull, remarkable for its flat retreating curve with an index

of 73-76; and the two nearly perfect skeletons found at Spy

(Belgium), the skulls of which exhibit enormous brow ridges

with cranial indices of 70 and 75. All these skulls, taken in

conjunction with other well-authenticated human remains such

as those found at La Naulette (Belgium), Shipka (Balkan

Peninsula), Olmo (Italy), Predmert (Bohemia) and in Argentina

and Brazil, make it possible to reconstruct anatomically the varying

types of pleistocene man, and to establish the fact that in

essential features the same primitive type has persisted through

all time. The skeleton bones show differences so slight as to

admit of pathological or other explanation. What Professor

Kollmann says of man to-day was true in the remotest ages.

Referring to Cuvier’s statement that from a single bone it is

possible to determine the very species to which an animal belongs,

he says, “Precisely on this ground I have mainly concluded that

the existence of several human species cannot be recognized, for

we are unacquainted with a single tribe from a single bone of

which we might with certainty determine to what species it

belonged.” Such differences as the bones exhibit are progressive

modifications towards the higher neolithic and modern types, and

are in themselves entirely incapable of supporting the theory

that the owner of the Trinil skull, say, and the “man of Spy”

belonged to separate species. All these “osseous remains”

belong to the palaeolithic period, and from the cranial indices

it is thus clear that palaeolithic man was long-headed. Neolithic

man is, speaking generally, round-headed, and it has been urged

that round-headedness is entirely synchronous with the neolithic

age, and that the long-headed palaeolithic species of mankind

gave place all at once to the round-headed neolithic species.

The point thus raised involves the physiological as well as,

indeed more than, the anatomical proofs of man’s specific unity.

850

2. All physiologists agree that species cannot breed with

species. Darwin himself laid it down as a fundamental principle.

If then the palaeolithic and neolithic types represented separate

species, they would be found to remain distinct through all time.

This is not the case. There is evidence that extreme dolichocephaly

continued into neolithic times, and was only slowly

modified into brachycephaly. In the neolithic caves of Italy,

Austria, Belgium, and the barrows of Great Britain, skulls of

all types are found. The later cave-dwellers and early dolmen

builders of Europe were at first long-headed, then of medium

type, and finally in some places exclusively round-headed. In

England the round-heads appear to be synchronous with the

metal age, as shown by the contents of the barrows, and, as on

the continental mainland, the two types gradually blended.

Permanent fertility between them in prehistoric Europe is thus

proved. And this is the case throughout the habitable globe.

An examination of the osseous remains of American man supports

the view that the human species has not varied since quaternary

times. The palaeolithic type is to be found among modern

European populations. Certain skulls from South Australia

seem cast in almost the same mould as the Neanderthal. After

thousands of years nearly pure descendants of quaternary man

are found among living races. And man’s mutual fertility in

prehistoric is repeated throughout historic times: strict racial

purity is almost unknown. Thus the unity of the species man

is proved by the test of fertility.

3. The works of early man everywhere present the most

startling resemblance. The palaeolithic implements all over the

globe are all of one pattern. “The implements in distant lands,”

writes Sir J. Evans, “are so identical in form and character with

the British specimens that they might have been manufactured by

the same hands.... On the banks of the Nile, many hundreds

of feet above its present level, implements of the European types

have been discovered; while in Somaliland, in an ancient river-valley

at a great elevation above the sea, Sir H.W. Seton-Karr

has collected a large number of implements formed of flint and

quartzite, which, judging from their form and character, might

have been dug out of the drift-deposits of the Somme and the

Seine, the Thames or the ancient Solent.” This identity in the

earliest arts is repeated in the later stages of man’s culture;

his arts and crafts, his manners and customs, exhibit a similarity

so close as to compel the presumption that all the races are but

divisions of one family. But perhaps the greatest psychical

proof of man’s specific unity is his common possession of language.

Theodore Waitz writes: “Inasmuch as the possession of a language

of regular grammatical structure forms a fixed barrier between

man and brute, it establishes at the same time a near relationship

between all people in psychical respects.... In the presence

of this common feature of the human mind, all other differences

lose their import” (Anthropology, p. 273). As Dr J.C. Prichard

urged, “the same inward and mental nature is to be recognized

in all races of men. When we compare this fact with the observations,

fully established, as to the specific instincts and separate

psychical endowments of all the distinct tribes of sentient beings

in the Universe we are entitled to draw confidently the conclusion

that all human races are of one species and one family.” It

has been argued that stock languages imply stock races, but

this assumption is untenable. There are some fifty irreducible

stock languages in the United States and Canada, yet, taking

into consideration the physical and moral homogeneity of the

American Indian races, he would be a reckless theorist who held

that there were therefore fifty separate human species. If it

were so, how have they descended? There are no anthropoid

apes in America, none of the ape family higher than the Cebidae,

from which it is impossible to trace men. Again, in Australia

there is certainly one stock language, yet there are not even

Cebidae. In Caucasia, there are many distinct forms of speech,

yet all the peoples belong to the Caucasic division of mankind.

Man, then, may be regarded as specifically one, and thus he

must have had an original cradle-land, whence the peopling of

the earth was brought about by migration. The evidence tends

to prove that the world was peopled by a generalized proto-human

form. Each division of mankind would thus have had

its pleistocene ancestors, and would have become differentiated

into races by the influence of climatic and other surroundings.

As to the man’s cradle-land there have been many theories, but the

weight of evidence is in favour of Indo-Malaysia.

Of all animals man’s range alone coincides with that of the

habitable globe, and the real difficulty of the “cradle-land”

theory lay in explaining how the human race spread to every

land. This problem has been met by geology, which proves

that the earth’s surface has undergone great changes since man’s

appearance, and that continents, long since submerged, once

existed, making a complete land communication from Indo-Malaysia.

The evidence for the Indo-African continent has been

summed up by R.D. Oldham,1 and proofs no less cogent are

available of the former existence of an Eurafrican continent,

while the extension of Australia in the direction of New Guinea

is more than probable. Thus the ancestor of man was free

to move in all directions over the eastern hemisphere. The

western hemisphere was more than probably connected with

Europe and Asia, in Tertiary times, by a continent, the existence

of which is evidenced by a submarine bank stretching from

Scotland through the Faeroes and Iceland to Greenland, and

on the other side by continuous land at what is now the Behring

Straits.

Acclimatization has been urged as an argument against the

cradle-land theory, but the peopling of the globe took place in

inter-Glacial if not pre-Glacial ages, when the climate was much

milder everywhere, and thus pleistocene man met no climatic

difficulties in his migrations.

Probably before the close of Palaeolithic times all the primary

divisions of man were specialized in their several habitats by the

influence of their surroundings. The profound effect of climate

is seen in the relative culture of races. Thus, tropical countries

are inhabited by savage or semi-savage peoples, while the higher

races are confined to temperate zones. The primary divisions

of mankind, Ethiopic, Mongolic, Caucasic, were certainly

differentiated in neolithic times, and these criteria had almost

certainly occurred not consecutively in one area but simultaneously

in several areas. A Negro was not metamorphosed into a

Mongol, nor the latter into a White, but the several semi-simian

precursors under varying environments developed into generalized

Negro, generalized Mongol, generalized Caucasian.

Taking, then, these three primary divisions as those into

851

which it is most reasonable broadly to divide mankind they

may be analysed as to their racial constituents and their habitats

as follows:—

1. Caucasic or White Man is best divided, following Huxley,

into (a) Xanthochroi or “fair whites” and (b) Melanochroi or

“dark whites.” (a) The first—tall, with almost colourless skin,

blue or grey eyes, hair from straw colour to chestnut, and skulls

varying as to proportionate width—are the prevalent inhabitants

of Northern Europe, and the type may be traced into North

Africa and eastward as far as India. On the south and west it

mixes with that of the Melanochroi and on the north and east

with that of the Mongoloids. (b) The “dark whites” differ

from the fair whites in the darkening of the complexion to

brownish and olive, and of the eyes and hair to black, while the

stature is somewhat lower and the frame lighter. To this division

belong a large part of those classed as Celts, and of the populations

of Southern Europe, such as Spaniards, Greeks and Arabs,

extending as far as India, while endless intermediate grades

between the two white types testify to ages of intermingling.

Besides these two main types, the Caucasic division of mankind

has been held with much reason to include such aberrant types

as the brown Polynesian races of the Eastern Pacific, Samoans,

Hawaiians, Maoris, &c., the proto-Malay peoples of the Eastern

archipelago, sometimes termed Indonesians, represented by

the Dyaks of Borneo and the Battaks of Sumatra, the Todas

of India and the Ainus of Japan.

2. Mongolic or Yellow Man prevails over the vast area lying

east of a line drawn from Lapland to Siam. His physical characteristics

are a short squat body, a yellowish-brown or coppery

complexion, hair lank, straight and black, flat small nose, broad

skull, usually without prominent brow-ridges, and black oblique

eyes. Of the typical Mongolic races the chief are the Chinese,

Tibetans, Burmese, Siamese; the Finnic group of races occupying

Northern Europe, such as Finns, Lapps, Samoyedes and

Ostyaks, and the Arctic Asiatic group represented by the Chukchis

and Kamchadales; the Tunguses, Gilyaks and Golds north of,

and the Mongols proper west of, Manchuria; the pure Turkic

peoples and the Japanese and Koreans. Less typical, but with

the Mongolic elements so predominant as to warrant inclusion,

are the Malay peoples of the Eastern archipelago. Lastly,

though differentiated in many ways from the true Mongol, the

American races from the Eskimo to the Fuegians must be

reckoned in the Yellow division of mankind.

3. Negroid or Black Man is primarily represented by the

Negro of Africa between the Sahara and the Cape district,

including Madagascar. The skin varies from dark brown to

brown-black, with eyes of the same colour, and hair usually

black and always crisp or woolly. The skull is narrow, with

orbital ridges not prominent, the jaws protrude, the nose is

flat and broad, and the lips thick and everted. Two important

families are classed in this division; some authorities hold,

as special modifications of the typical Negro to-day, others as

actually nearer the true generalized Negroid type of neolithic

times. First are the Bushman of South Africa, diminutive

in stature and of a yellowish-brown colour: the neighbouring

Hottentot is believed to be the result of crossing between the

Bushman and the true Negro. Second are the large Negrito

family, represented in Africa by the dwarf races of the equatorial

forests, the Akkas, Batwas, Wochuas and others, and beyond

Africa by the Andaman Islanders, the Aetas of the Philippines,

and probably the Senangs and other aboriginal tribes of the

Malay Peninsula. The Negroid type seems to have been the

earliest predominant in the South Sea islands, but it is impossible

to say certainly whether it is itself derived from the Negrito,

or the latter is a modification of it, as has been suggested above.

In Melanesia, the Papuans of New Guinea, of New Caledonia,

and other islands, represent a more or less Negroid type, as did

the now extinct Tasmanians.

Excluded from this survey of the grouping of Man are the

aborigines of Australia, whose ethnical affinities are much

disputed. Probably they are to be reckoned as Dravidians, a

very remote blend of Caucasic and Negro man. For a detailed

discussion of the branches of these three main divisions of Man

the reader must refer to articles under race headings, and to

Negro; Negritos; Mongols; Malays; Indians, North

American; Australia; Africa; &c., &c.

Bibliography.—J.C. Prichard, Natural History of Man (London,

1843), Researches into the Physical History of Mankind (5 vols.,

1836-1847); T.H. Huxley, Man’s Place in Nature (London, 1863),

and “Geographical Distribution of Chief Modifications of Mankind,”

in Journ. Anthropological Institute for 1870; Theodore Waitz,

Anthropologie der Naturvölker (1859-1871); A. de Quatrefages,

Histoire générale des races humaines (Paris, 1889); E.B. Tylor,

Anthropology (1881); Lord Avebury, Prehistoric Times (1865;

6th ed., 1900) and Origin of Civilization (1870; 6th ed., 1902); F.

Ratzel, History of Mankind (Eng. trans., 1897); A.H. Keane,

Ethnology (2nd ed., 1897), and Man: Past and Present (2nd ed.,

1899); G. de Mortillet, Le Préhistorique (Paris, 1882; 3rd ed.,

1900); D.G. Brinton, Races and Peoples (1890); J. Deniker, The

Races of Man (London, 1900); Hutchinson’s Living Races of Mankind

(1906).

1 Writing in the Geographical Journal, March 1894, on “Evolution

of Indian Geography,” he says: “The plants of Indian and African

coal measures are without exception identical, and among the few

animals which have been found in India one is indistinguishable

from an African species, another is closely allied, and both faunas

are characterized by the very remarkable genus group of reptiles

comprising the Dicynodon and other allied forms (see Manual of

Geology of India, 2nd ed. p. 203). These, however, are not the only

analogies, for near the coast of South Africa there are developed a

series of beds containing the plant fossils in the lower part and

marine shells in the upper, known as the Uitenhage series, which

corresponds exactly to the small patches of the Rajmahál series

along the east coast of India. The few plant forms found in the

lower beds of Africa are mostly identical with or closely allied to the

Rajmahál species, while of the very few marine shells in the Indian

outcrops, which are sufficiently well preserved for identification, at

least one species is identical with an African form. These very

close relationships between the plants and animals of India and

Africa at this remote period appear inexplicable unless there were

direct land communications between them over what is now the

Indian Ocean. On the east coast of India in the Khasi Hills, and

on the coast of South Africa, the marine fossils of late Jurassic and

early cretaceous age are largely identical with, or very closely allied

to each other, showing that they must have been inhabitants of one

and the same great sea. In western India the fossils of the same age

belong to a fauna which is found in the north of Madagascar, in

northern and eastern Africa, in western Asia, and ranges into Europe—a

fauna differing so radically from that of the eastern exposures

that only a few specimens of world-wide range are found in both.

Seeing that the distances between the separate outcrops containing

representatives of the two faunas are much less than those separating

the outcrops from the nearest ones of the same fauna, the only

possible explanation of the facts is that there was a continuous

stretch of dry land connecting South Africa and India and separating

two distinct marine zoological provinces.”

ETHYL, in chemistry, the name given to the alkyl radical

C2H5. The compounds containing this radical are treated

under other headings; the hydride is better known as ethane,

the alcohol, C2H5OH, is the ordinary alcohol of commerce, and

the oxide (C2H5)2O is ordinary ether.

ETHYL CHLORIDE, or Hydrochloric Ether, C2H5Cl, a

chemical compound prepared by passing dry hydrochloric acid

gas into absolute alcohol. It is a colourless liquid with a sweetish

burning taste and an agreeable odour. It is extremely volatile,

boiling at 12.5° C. (54.5° F.), and is therefore a gas at ordinary

room temperatures; it is stored in glass tubes fitted with screw-capped

nozzles. The vapour burns with a smoky green-edged

flame. It is largely used in dentistry and slight surgical operations

to produce local anaesthesia (q.v.), and is known by the

trade-name kelene. More volatile anaesthetics such as anestile

or anaesthyl and coryl are produced by mixing with methyl

chloride; a mixture of ethyl and methyl chlorides with ethyl

bromide is known as somnoform.

ETHYLENE, or Ethene, C2H4, or H2C:CH2, the first representative

of the series of olefine hydrocarbons, is found in coal

gas. It is usually prepared by heating a mixture of ethyl alcohol

and sulphuric acid. G.S. Newth (Jour. Chem. Soc., 1901, 79,

p. 915) obtains a purer product by dropping ethyl alcohol into

syrupy phosphoric acid (sp. gr. 1.75) warmed to 200° C., subsequently

raising the temperature to 220° C. It can also be

obtained by the action of sodium on ethylidene chloride (B.

Tollens, Ann., 1866, 137, p. 311); by the reduction of copper

acetylide with zinc dust and ammonia; by heating ethyl

bromide with an alcoholic solution of caustic potash; by passing

a mixture of carbon bisulphide and sulphuretted hydrogen over

red-hot copper; and by the electrolysis of a concentrated solution

of potassium succinate,

(CH2·CO2K)2 + 2H2O = C2H4 + 2CO2 + 2KOH + H2.

It is a colourless gas of somewhat sweetish taste; it is slightly

soluble in water, but more so in alcohol and ether. It can be

liquefied at −1.1° C., under a pressure of 42½ atmos. It solidifies

at −181° C. and melts at −169° C. (K. Olszewski); it boils at

−105° C. (L.P. Cailletet), or −102° to −103° C. (K. Olszewski).

Its critical temperature is 13° C., and its specific gravity is 0.9784

(air = 1). The specific gravity of liquid ethylene is 0.386 (3° C.).

Ethylene burns with a bright luminous flame, and forms a very

explosive mixture with oxygen. For the combustion of ethylene

see Flame. On strong heating it decomposes, giving, among

other products, carbon, methane and acetylene (M. Berthelot,

Ann., 1866, 139, p. 277). Being an unsaturated hydrocarbon,

it is capable of forming addition products, e.g. it combines with

hydrogen in the presence of platinum black, to form ethane,

C2H6, with sulphur trioxide to form carbyl sulphate, C2H4(SO3)2,

with hydrobromic and hydriodic acids at 100° C. to form ethyl

bromide, C2H5Br, and ethyl iodide, C2H5I, with sulphuric acid

at 160-170° C. to form ethyl sulphuric acid, C2H5·HSO4, and with

hypochlorous acid to form glycol chlorhydrin, Cl·CH2·CH2·OH.

Dilute potassium permanganate solution oxidizes it to ethylene

glycol, HO·CH2·CH2·OH, whilst fuming nitric acid converts it

into oxalic acid. Several compounds of ethylene and metallic

852

chlorides are known; e.g. ferric chloride in the presence of ether

at 150° C. gives C2H4·FeCl3·2H2O (J. Kachtler, Ber., 1869, 2,

p. 510), while platinum bichloride in concentrated hydrochloric

acid solution absorbs ethylene, forming the compound C2H4·PtCl2

(K. Birnbaum, Ann., 1868, 145, p. 69).

ÉTIENNE, CHARLES GUILLAUME (1778-1845), French

dramatist and miscellaneous writer, was born near Saint Dizier,

Haute Marne, on the 5th of January 1778. He held various

municipal offices under the Revolution and came in 1796 to

Paris, where he produced his first opera, Le Rêve, in 1799, in

collaboration with Antoine Frédéric Gresnick. Although

Étienne continued to write for the Paris theatres for twenty

years from that date, he is remembered chiefly as the author

of one comedy, which excited considerable controversy. Les

Deux Gendres was represented at the Théâtre Français on the

11th of August 1810, and procured for its author a seat in the

Academy. A rumour was put in circulation that Étienne had

drawn largely on a manuscript play in the imperial library,

entitled Conaxa, ou les gendres dupés. His rivals were not slow

to take up the charge of plagiarism, to which Étienne replied

that the story was an old one (it existed in an old French fabliau)

and had already been treated by Alexis Piron in Les Fils ingrats.

He was, however, driven later to make admissions which at

least showed a certain lack of candour. The bitterness of the

attacks made on him was no doubt in part due to his position

as editor-in-chief of the official Journal de l’Empire. His next

play, L’Intrigante (1812), hardly maintained the high level of

Les Deux Gendres; the patriotic opera L’Oriflamme and his lyric

masterpiece Joconde date from 1814. Étienne had been secretary

to Hugues Bernard Maret, duc de Bassano, and in this capacity

had accompanied Napoleon throughout his campaigns in Italy,

Germany, Austria and Poland. During these journeys he produced

one of his best pieces, Brueys et Palaprat (1807). During

the Restoration Étienne was an active member of the opposition.

He was seven times returned as deputy for the department of

Meuse, and was in full sympathy with the revolution of 1830,

but the reforms actually carried out did not fulfil his expectations,

and he gradually retired from public life. Among his other

plays may be noted: Les Deux Mères, Le Pacha de Suresnes, and

La Petite École des pères, all produced in 1802, in collaboration

with his friend Gaugiran de Nanteuil (1778-1830). With Alphonse

Dieudonné Martainville (1779-1830) he wrote an Histoire du

Théâtre Français (4 vols., 1802) during the revolutionary period.

Étienne was a bitter opponent of the romanticists, one of whom,

Alfred de Vigny, was his successor and panegyrist in the Academy.

He died on the 13th of March 1845.

His Œuvres (6 vols., 1846-1853) contain a notice of the author by

L. Thiessé.

ETIQUETTE, a term for ceremonial usage, the rules of behaviour

observed in society, more particularly the formal rules

of ceremony to be observed at court functions, &c., the procedure,

especially with regard to precedence and promotions

in an organized body or society. Professions, such as the law

or medicine, observe a code of etiquette, which the members

must observe as protecting the dignity of the profession and

preventing injury to its members. The word is French. The

O. Fr. estiquette or estiquet meant a label, or “ticket,” the true

English derivative. The ultimate origin is Teutonic, from

sticken, to post up, stick, affix. Cotgrave explains the word in

French as a billet for the benefit or advantage of him that receives

it, a form of introduction and also a notice affixed at the gate

of a court of law. The development of meaning in French from

a label to ceremonial rules is not difficult in itself, but, as the

New English Dictionary points out, the history has not been

clearly established.

ETNA (Gr. Αἴτνη, from αἴθω, burn; Lat. Aetna), a volcano on

the east coast of Sicily, the summit of which is 18 m. N. by W.

of Catania. Its height was ascertained to be 10,758 ft. in 1900,

having decreased from 10,870 ft. in 1861. It covers about 460

sq. m., and by rail the distance round the base of the mountain

is 86 m., though, as the railway in some places travels high, the

correct measurement is about 91 m. The height cannot have

been very different in ancient times, for the so-called Torre del

Filosofo, which is only 1188 ft. below the present summit, is a

building of Roman date. The shape is that of a truncated cone,

interrupted on the west by the Valle del Bove, a huge sterile

abyss, 3 m. wide, bounded on three sides by perpendicular

cliffs (2000 to 4000 ft.). Its south-west portion, which is the

deepest, was perhaps the original crater. There are also some

200 subsidiary cones, some of them over 3000 ft. high, which

have risen over lateral fissures. On the slopes of the mountain

there are three distinct zones of vegetation, distinguished by

Strabo (vi. p. 273 ff.). The lowest, up to about 3000 ft., is the

zone of cultivation, where vegetables, and above them where

water is more scanty, vines and olives flourish. Owing to its

extraordinary fertility it is densely populated, having 930

inhabitants per sq. m. below 2600 ft., and 3056 inhabitants

per sq. m. in the triangle between Catania, Nicolosi and Acireale.

The next zone is the wooded zone, and is hardly inhabited, only

a few isolated houses occurring. The lower part of it (up to

about 6000 ft.) consists chiefly of forests of evergreen pines

(Pinus nigricans), the upper (up to about 6800 ft.) of birch woods

(Betula alba). A few oaks and red beeches occur, while chestnut

trees grow anywhere between 1000 and 5300 ft. In the third and

highest zone the vegetation is stunted, and there is a narrow zone

of sub-Alpine shrubs, but no Alpine flora. In the last 2000 ft.

five phanerogamous species only are to be found, the first three

of which are peculiar to the mountain: Senecio Etnensis (which

is found quite close to the crater), Anthemis Etnensis, Robertsia

taraxacoides, Tanacetum vulgare and Astragalus siculus. No trace

of animal life is to be found in this zone; for the greater part of

the year it is covered with snow, but by the end of summer this

has almost all melted, except for that preserved in the covered

pits in which it is stored for use for cooling liquids, &c., in Catania

and elsewhere. The ascent is best undertaken in summer or

autumn. From the village of Nicolosi, 9 m. to the N.W. of

Catania, about 7 or 8 hours are required to reach the summit.

Thucydides mentions eruptions in the 8th and 5th centuries B.C.,

and others are mentioned by Livy in 125, 121 and 43 B.C. Catania

was overwhelmed in 1169, and many other serious eruptions are

recorded, notably in 1669, 1830, 1852, 1865, 1879, 1886, 1892,

1899 and March 1910.

According to Lyell, Etna is rather older than Vesuvius—perhaps

of the same geological age as the Norwich Crag. At

Trezza, on the eastern base of the mountain, basaltic rocks occur

associated with fossiliferous Pliocene clays. The earliest eruptions

of Etna are older than the Glacial period in Central and

Northern Europe. If all the minor cones and monticules could be

stripped from the mountain, the diminution of bulk would be

extremely slight. Lyell concluded that, although no approximation

can be given of the age of Etna, “its foundations were laid

in the sea in the newer Pliocene period.” From the slope of the

strata from one central point in the Val del Bue he further

concluded that there once existed a second great crater of

permanent eruption. The rocks erupted by Etna have always

been very constant in composition, viz. varieties of basaltic lava

and tuff containing little or no olivine—the rock type known as

labradorite. At Acireale the lava has assumed the prismatic

or columnar form in a striking manner; at the rock of Aci it is

in parts spheroidal. The Grotte des Chèvres has been regarded

as an enormous gas-bubble in the lava. The remarkable stability

of the mountain appears to be due to the innumerable dikes

which penetrate the lava flows and tuff beds in all directions

and thus bind the whole mass together.

From the earliest times the mountain has naturally been the

subject of legends. The Greeks believed it to be either the

mountain with which Zeus had crushed the giant Typhon (so

Pindar, Pyth. i. 34 seq.; Aeschylus, Prometheus Vinctus, 351

seq.; Strabo xiii. p. 626), or Enceladus (Virgil, Georg. i. 471;

Oppian, Cyn. i. 273), or the workshop of Hephaestus and the

Cyclopes (Cic. De divin. ii. 19; cf. Lucil., Aetna, 41 seq., Solin,

11). Several Roman writers, on the other hand, attempted to

explain the phenomena which it presented by natural causes

(e.g. Lucretius vi. 639 seq.; Lucilius, Aetna, 511 seq.). Ascents

853

of the mountain were not infrequent in those days—one was

made by Hadrian.

See Sartorius von Waltershausen, Atlas des Ätna (Leipzig, 1880);

E. Chaix, Carta Volcanologica e topographica dell’ Etna (showing lava

streams up to 1892); G. de Lorenzo, L’Etna (Bergamo, 1907).

ETNA, a borough of Allegheny county, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.,

in the western part of the state, on the W. bank of the Allegheny

river (about 5 m. from its junction with the Monongahela),

and about 2 m. N. of the city of Pittsburg, of which it is a suburb.

Pop. (1880) 2334; (1890) 3767; (1900) 5384 (1702 foreign-born);

(1910) 5830. It is served by the Pennsylvania railway and

by electric lines. Among its industrial establishments are

rolling mills, tube and pipe works, furnaces, steel mills, a brass

foundry, and manufactories of electrical railway supplies, boxes,

asbestos coverings, enamel work and ice. The city’s industrial

history dates from 1820, when a small factory for the manufacture

of scythes and sickles was set up. Natural gas, piped from

Butler county, was early used here as a fuel in the iron mills.

Etna, formerly called Steuart’s Town, was incorporated as a

borough in 1869.

ETON, a town of Buckinghamshire, England, on the north

(left) bank of the river Thames, opposite Windsor, within which

parliamentary borough it is situated. Pop. of urban district

(1901) 3301. It is famous for its college, the largest of the ancient

English public schools. The “King’s College of Our Lady of

Eton beside Windsor” was founded by Henry VI. in 1440-1441,

and endowed mainly from the revenues of the alien priories suppressed

by Henry V. The founder followed the model established

by William of Wykeham in his foundations of Winchester

and New College, Oxford. The original foundation at Eton

consisted of a provost, 10 priests, 4 clerks, 6 choristers, a schoolmaster,

25 poor and indigent scholars, and the same number

of poor men or bedesmen. In 1443, however, Henry considerably

altered his original plans; the number of scholars was increased

to 70, and the number of bedesmen reduced to 13. A connexion

was then established, and has been maintained ever since,

though in a modified form, between Eton and Henry’s foundation

of King’s College, Cambridge. One of the king’s chief advisers

was William of Waynflete, who had been master of Winchester

College, and was appointed provost of Eton in 1443. Among

further alterations to the foundation in this year was the establishment

of commensales or commoners, distinct from the scholars;

and these under the name of “oppidans” now form the principal

body of the boys. The college survived with difficulty the unsettled

period at the close of Henry’s reign; while Edward IV.

curtailed its possessions, and was at first desirous of amalgamating

it with the ecclesiastical foundation of St George, Windsor

Castle. In 1506 the annual revenue amounted to £652; and

through benefactions and the rise in the value of property the

college has grown to be very richly endowed. In 1870 commissioners

under an act of 1868 appointed the governing body

of the college to consist of the provost of Eton, the provost of

King’s College, Cambridge, five representatives nominated respectively

by the university of Oxford, the university of Cambridge,

the Royal Society, the lord chief justice and the masters,

and four representatives chosen by the rest of the governing

body. By this body the foundation was in 1872 made to consist

of a provost and ten fellows (not priests, but merely the members

of the governing body other than the provost), a headmaster

of the school, and a lower master, at least seventy scholars (known

as “collegers”), and not more than two chaplains or conducts.

Originally it was necessary that the scholars should be born in

England, of lawfully married parents, and be between eight and

sixteen years of age; but according to the statutes of 1872 the

scholarships are open to all boys who are British subjects, and

(with certain limitations as to the exact date of birth) between

twelve and fifteen years of age. A number of foundation

scholarships for King’s College, Cambridge, are open for competition

amongst the boys; and there are besides several other

valuable scholarships and exhibitions, most of which are tenable

only at Cambridge, some at Oxford, and some at either university.

The teaching embraces the customary range of classical and

modern subjects; but until the first half of the 19th century

the normal course of instruction remained almost wholly classical;

and although there were masters for other subjects, they were

unconnected with the general business of the school, and were

attended at extra hours.

The school buildings were founded in 1441 and occupied in

part by 1443, but the whole original structure was not completed

till fifty years later. The older buildings consist of two quadrangles,

built partly of freestone but chiefly of brick. The outer

quadrangle, or school-yard, is enclosed by the chapel, upper and

lower schools, the original scholars’ dormitory (“long chamber”),

now transformed, and masters’ chambers. It has in its centre a

bronze statue of the royal founder. The buildings enclosing the

inner or lesser quadrangle contain the residence of the fellows,

the library, hall and various offices. The chapel, on the south

side of the school-yard, represents only the choir of the church

which the founder originally intended to build; but as this was

not completed Waynflete added an ante-chapel. The chapel was

built upon a raised platform of stone, as was the hall, in order

to lift it above the flood-level of the Thames. It contains some

interesting monuments of provosts of the college and others,

and at the west end of the ante-chapel is a fine marble statue of