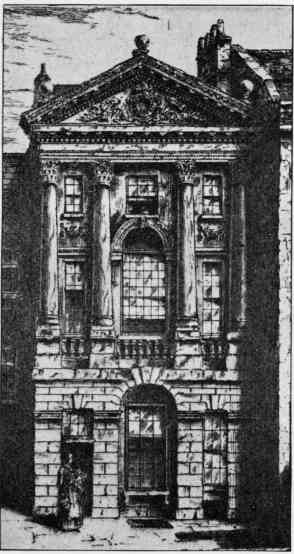

The Postmaster's Office, Bristol.

The Postmaster's Office, Bristol.From a photograph by Mr. Protheroe, Wine St., Bristol.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Bristol Royal Mail, by R. C. Tombs

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Bristol Royal Mail

Post, Telegraph, and Telephone

Author: R. C. Tombs

Release Date: November 2, 2010 [EBook #34197]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BRISTOL ROYAL MAIL ***

Produced by Adrian Mastronardi, Henry Gardiner, The

Philatelic Digital Library Project at http://www.tpdlp.net

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note: No copyright date is indicated in the source material, but the last date mentioned is November, 1899.

The Postmaster's Office, Bristol.

The Postmaster's Office, Bristol.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| DEVELOPMENT OF THE MAIL SERVICES. RALPH ALLEN. 1532-1764. | 5 |

| Chapter II. | |

| MAIL COACH ERA. JOHN PALMER. 1770-1818. | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| 1818 ONWARDS. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE. OLD MAIL GUARDS. | 35 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| VICTORIAN ERA, 1837-1899. MAIL TRANSPORT BY RAILWAY. TRAVELLING POST OFFICES. | 49 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| BRISTOL POSTMASTERS. 1678-1899. | 68 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| NOTABLE POST OFFICE SERVANTS OF BRISTOL ORIGIN. | 82 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| POST OFFICE BUILDINGS. | 89 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE LOCAL POST OFFICE IN EARLY DAYS. SIR ROWLAND HILL. RECENT PROGRESS. | 121 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| BRISTOL AS A MAIL PORT. | 141 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| POSTAL SERVICE. STAFF: ITS COMPOSITION, DUTIES, RESPONSIBILITIES. VOLUME OF WORK. |

160 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| CHRISTMAS AND ST. VALENTINE SEASONS. | 175 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| PUBLIC OFFICE: ITS BUSINESS. THE SAVINGS BANK. PUBLIC COMMUNICATIONS. |

186 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| TELEGRAPHS. TELEPHONES. EXPRESS DELIVERY. | 198 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| TELEGRAPH MESSENGERS. | 222 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| LETTER DELIVERY SYSTEM. POSTMEN: THEIR DUTIES AND RECREATIONS. | 234 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| POST LETTER BOXES: POSITION, VIOLATION, PECULIAR USES. | 253 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| RURAL DISTRICT SUB-POSTMASTERS. RURAL POSTMEN. INCIDENTS. | 257 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| GENERAL FREE DELIVERY OF LETTERS. | 287 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| RETURNED LETTER OFFICE. | 292 |

| THE POSTMASTER'S OFFICE, BRISTOL | Page 0 |

| RALPH ALLEN OF CROSS POST FAME | 6 |

| HIS RESIDENCE AT PRIOR PARK, BATH | 9 |

| HIS TOWN HOUSE IN BATH | 13 |

| HIS TOMB AT CLAVERTON | 16 |

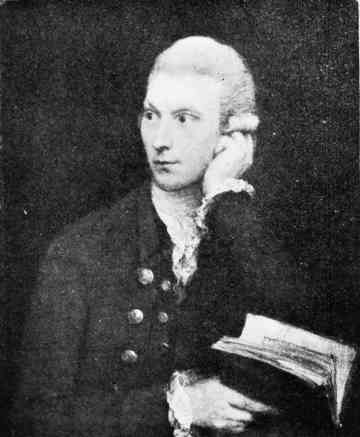

| JOHN PALMER, INTRODUCER OF MAIL COACHES | 18 |

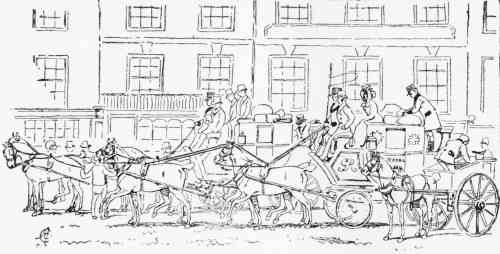

| OLD ENGLISH "FLYING" MAIL COACH | 21 |

| MAIL COACH PLATE DEDICATED TO PALMER | 34 |

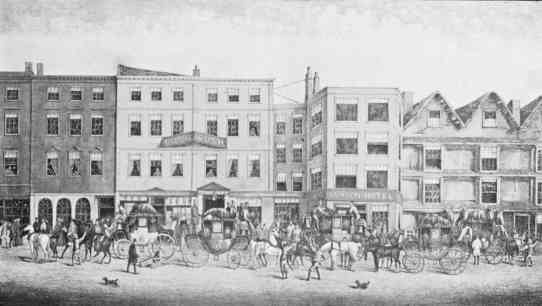

| THE WEST COUNTRY MAIL COACHES ABOUT TO LEAVE PICCADILLY | 36 |

| THE LAST OF THE MAIL GUARDS | 44 |

| ARRIVAL OF THE BATH AND BRISTOL MAIL COACH AT ROADSIDE INN | 48 |

| START OF MAIL COACHES FROM BUSH INN, BRISTOL | 52 |

| THE OLD PASSAGE, AUST | 56 |

| JOHN GARDINER | 71 |

| THOMAS TODD WALTON, SENIOR | 72 |

| THOMAS TODD WALTON, JUNIOR | 74 |

| EDWARD CHADDOCK SAMPSON | 79 |

| SIR FRANCIS FREELING, BART | 83 |

| THE BRISTOL HEAD POST OFFICE IN 1899 | 117 |

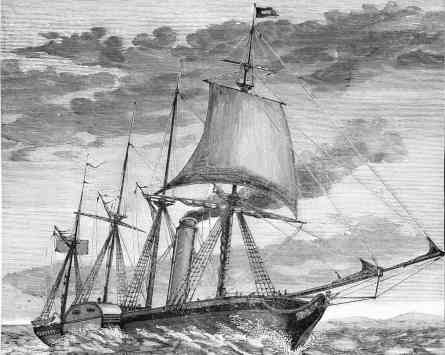

| THE "GREAT WESTERN" | 152 |

| R.M.S. "MONTEREY" | 159 |

| THE PUBLIC HALL OF THE BRISTOL POST OFFICE | 186 |

| THE TELEGRAPH INSTRUMENT ROOM, BRISTOL | 204 |

| CRIBBS CAUSEWAY POST OFFICE | 261 |

| MR. EDWARD BIDDLE | 263 |

| LETTER BOX AT WINTERBOURNE | 269 |

| HANNAH BREWER, THE BITTON POSTWOMAN | 276 |

In these days when books on every conceivable subject are written in their thousands annually; when monthly journals are produced by scores, and daily newspapers in hundreds, to supply the public with a record of the world's doings; and when readers are found for them all, it may not be thought unfitting that each large mail centre in the United Kingdom which contributes by its postal and telegraph organisation to the dissemination of much of this literature, should in its turn have some record of its own doings. This present compilation has, therefore, been undertaken with that object in view, as regards the Bristol Post Office, and in the hope that the facts, figures, and incidents contained in it relating to past doings and present days and present ways may prove of interest to the inhabitants of the County and City, and its surrounding districts, and in an unpretentious way [Pg ii] commence, or add to, local Post Office history, and demonstrate that though Bristol is not, unfortunately, the leading provincial seaport, as of yore, she has not lagged one step behind her competitors in respect of postal progress.

The profit which may accrue from the publication of The Bristol Royal Mail will be devoted exclusively to the Rowland Hill Memorial and Benevolent Fund, the chief patron of which is Her Most Gracious Majesty the Queen-Empress, who is about to show her great interest in works of the kind by visiting our ancient city to open the new Convalescent Home. The object of the fund is the relief of all Post Office servants throughout the United Kingdom, who, through no fault of their own, have fallen into necessitous circumstances. It also affords assistance to their widows and orphans, for whom no provision is made under the Superannuation Acts. The fund is managed by a body of trustees, who are assisted by a committee of recommendation composed of officers of the Post Office. The trustees are well-known gentlemen of high standing and repute in the city of London, to whose benevolent efforts on behalf of the department the fund owes its origin. [Pg iii] The Superannuation Acts afford pensions to those who have been in the Post Office not less than ten years. Sometimes a deserving and distressed Post Office servant has not served long enough to qualify for a pension, and sometimes help is needed by persons whose time has been partly spent in the postal service, but who, because they have been permitted to carry on some other occupation, are not entitled by law to any pension at all. A pension, even if it should prove to be sufficient for the pensioner's own support, ceases at death, and the widow and orphans are often left destitute. There are more than eighty-one thousand, and, counting those employed only a portion of their time, nearly one hundred and fifty thousand servants in the Post Office; and in comparison with the number of persons amongst whom cases needing relief may arise, the assured income at the disposal of the trustees of the fund is still inadequate. In the period since 1893 the trustees have granted to necessitous cases in the Bristol district £120, so that any proceeds from the sale of this book will be bestowed where such bestowal is certainly due.

It is right to state that some of the information [Pg iv] in these pages has been derived from The History of the Post Office, by the late Mr. Herbert Joyce, C.B.; Forty Years at the Post Office, by Mr. F. E. Baines, C.B.; The Royal Mail, by Mr. J. Wilson Hyde; and from St. Martin's-le-Grand Magazine, also Latimer's Annals of Bristol. Thanks are due also to Mr. Norris Mathews, the Bristol City Librarian, for his courtesy in permitting and facilitating access to old records in the Public Library; to Mr. H. J. Spear, Secretary to the Chamber of Commerce; to the proprietors of the Times and Mirror, for allowing inspection of their old files; and for illustrations to Mr. A. F. Walbrook, of the Bath Chronicle; to the proprietor, Black and White, and many others whose kindness is hereby acknowledged.

It appears that before Post Offices were established special messengers were employed to carry letters. It is recorded that such a special messenger was paid the sum of one penny for carrying a letter from Bristol to London in the year 1532, but the record affords no further particulars as to the service, and the assumption is that the special messenger was, in his own person, a rough-and-ready "post." Later on, a post would be suddenly established for a particular purpose, and as soon abandoned when no longer specially required. Thus in the year 1621 a post to Ireland—Irish firms being then considered [Pg 6] to require "oftener despatches and more expedition"—was set up by way of Bristol, only to be discontinued in a few years.

Ralph Allen.

Ralph Allen.There was in 1660 a direct but irregular post between London and some of the larger provincial towns, but there were no cross posts between two towns not being on the same post road. Letters could only circulate from one post road to another through London, and such circulation through London involved additional rates of postage. Bristol and Exeter are less than eighty miles apart, but, not being on the same post road, letters from one place to the other passed through London, and were charged, if single, 6d., thus:—one rate of 3d. from Exeter to London, and another rate of 3d. from London to Bristol. This was in conformity with a system established in the reign of Charles II. That system went on until 1696 when a post was established between Bristol and Exeter, that being the first cross post in the kingdom authorised by the Monarch's own personal assent. From Bristol the posts went on Mondays and Fridays, starting at 10.0 in the morning. The posts left Exeter on Wednesdays and Saturdays at 4.0 in the afternoon, [Pg 7] and arrived at Bristol at the same hour on the following days. Under this cross post plan, the two towns being less than eighty miles apart, the charge was reduced to 2d. for a single letter. In three or four years the new post produced a profit of £250 a year. In 1678 Provost Campbell established a coach to run from Glasgow to Edinburgh, "drawn by sax able horses, to leave Edinboro' ilk Monday morning, and return again (God willing) ilk Saturday night." In 1700 the service between Bristol and London became fixed, and on alternate days at irregular hours, depending upon the state of the weather and the roads, the extent of the journey and the caprices of the postboys and the sorry nags that carried them, the mail arrived in Bristol. There were, however, only a mere handful of letters and newspapers. At the end of the same year, the Post Office authorities in London, after being earnestly petitioned by local merchants, counselled the Government to establish a "cross post" from this city to Chester. Up to that time the Bristol letters to Chester, Shrewsbury, Worcester, and Gloucester had been carried round by London under the system already described, [Pg 8] involving double postage and great delay. The effect of this system, as on the Bristol and Exeter road, had been to throw nearly all the letters into the hands of public carriers, by whose wagons they were conveyed more quickly than by the postboys through London, and at a cheaper rate. Moved by the success of the new cross posts from Bristol to Exeter, the Treasury consented to the starting of the Chester service. The Post Office reported to the Treasury in March, 1702, that the profit for the first eighteen months of the Chester service had been about £156. The accounts of Henry Pyne, the Bristol postmaster, appended to the report in the State papers, show that so far as this part of the service was concerned, he had received £168 for letters by this post, whilst his expenses had been £60.

The people of Cirencester and Exeter, hearing of the Chester concession, hastened to complain of shortcomings affecting themselves. The Devon clothiers had a considerable trade with the wool dealers of the district of Cirencester, which town was served by the postboys riding between Gloucester and London, with a branch postboy mail to [Pg 9] Wotton-under-Edge. By there being no direct postal service of any kind between Bristol and Wotton-under-Edge, correspondence between Exeter and Cirencester had to be sent viâ London, and a fortnight elapsed between the despatch of a letter and the receipt of an answer, the result being that not one letter in twenty was sent through the post. All that was needed to shorten the transit from fourteen days to four was to put Bristol in direct communication with Wotton, the expense being estimated at only £30 a year. The Government declined to comply with this reasonable request, and nothing was done!

Prior Park, Bath.

Prior Park, Bath.Soon after this time a Post Office reformer arose in our immediate district in the person of Ralph Allen. He, unlike later reformers, passed all his working days in the Post Office service. Born at the "Duke William Inn," at St. Blazey Highway, in Cornwall in about 1693, he went as a boy to help his grandmother, who was postmistress at St. Columb. In 1710 he was transferred as a clerk to Bath, and on the 26th March, 1712, he became postmaster of that city, in succession to one Mary Collins, and in that year appears to have taken over the management of [Pg 10] the Bristol and Exeter Cross Road Post, previously farmed by Joseph Quash, postmaster of Exeter. In 1720 Ralph Allen contracted to farm the cross-country posts throughout the country generally, and to carry the mails by what were subsequently known as "Allen's Postboys," who were supposed to travel on horseback at a pace averaging five miles an hour. A robbery from these postboys carrying the mails between London and Bristol was a common occurrence. Two men were executed in April, 1720, for having twice committed that crime, yet the letter bags were again stolen seven times during the following twelve months. The London Journal of August 27th remarked: "It is computed that the traders of Bristol have received £60,000 damages by the late robberies of the mail." In 1722 the postboys were robbed twice in a single week, and for the crimes three men were executed in London. Another incident of the kind worthy of mentioning occurred in September, 1738. The bag then carried off by three highwaymen contained a reprieve for a man lying under sentence of death in Newgate, and a second reprieve despatched after the robbery became known would have arrived too late to save the man's [Pg 11] life, had not the magistrates postponed the execution for a day or two in order that it might not clash with the festivities of a new Mayor's inauguration.

About 1732 the Bristol riding boys were deprived of their perquisite of 1d. a letter for "dropping of letters" at the towns and villages through which they passed. This was done because the postboys not only carried letters which they picked up on the road and did not account for at the next post office of call, but even went to the length of taking out letters from the mail bags when those bags were, as was the case sometimes, not properly chained and sealed. In connection with Ralph Allen's "By-Posts," in the year 1735 arrangements were made so that the mails sent from Manchester, Liverpool, or any other place in Lancashire, to Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, Somerset, Devon, etc., might be answered four days sooner than they could possibly have been answered before. In 1740 a new branch by-post was established from Bristol and Bath to Salisbury, through Bradford, Trowbridge, Devizes, Lavington, Tinhead, Westbury, Warminster, Heytesbury, and Wilton. In 1741 the growth of trade and population encouraged the [Pg 12] Bristol citizens to appeal to the Ministry for an improvement in the postal communication with London, which was still limited to three days per week. Yielding to this pressure, Allen converted the tri-weekly posts into six-day posts in June, 1741. The post began to run every day of the week, except Sunday, between London and Bristol, and all intervening towns participated in the benefit. In 1746 a further extension took place, whereby letters were conveyed six days in every week, instead of three days, at Mr. Allen's expense, between London and Wells, Bridgwater, Taunton, Wellington, Tiverton, and Exeter, through Bristol. The mail service is not in further evidence in local history until 1753, when the Bristol merchants again showed themselves tenacious of their rights, and waged a bitter war against the Postmasters-General in respect of the imposition of a double rate of postage on letters which, although under an ounce in weight, contained patterns of silk or cotton or samples of grain. There was a lawsuit, and the Bristol merchants won it.

A Government notification in the local newspapers of the 4th September, 1752, announced an acceleration [Pg 13] of the mails between the Southern Counties and Bristol. In future a postboy was to leave Salisbury on Mondays at six o'clock in the morning, to arrive at Bath (a distance of about thirty-nine miles) at eight or nine at night, and to leave Bath for Bristol at six next morning. On Wednesdays and Fridays the departure from Salisbury was in the evening, the journey occupying about nineteen hours. By this arrangement letters from Portsmouth were received in this city two days earlier than before.

Ralph Allen's Town House in Bath.

Ralph Allen's Town House in Bath.Ralph Allen's improvements had great influence in the Post Office services in this western city. The profits on the contracts enabled Allen to take up his residence at Prior Park, Bath, one of the finest Italian houses in England, in addition to having a grand house in the City. It is said that the profits which accrued to him from his long contracts amounted to about half a million of money.

Mansions so lordly are not for the hardest and best workers in the Post Office field of present times, for the nation does not reward its great men so liberally as then. Nowadays an introducer of the inland parcel post service, the foreign parcel post service, an improver of the telegraph service, [Pg 14] and leader in bringing about vastly accelerated mail services throughout the country,—works of great moment, even if not comparable with Ralph Allen, John Palmer, or Rowland Hill's great achievements,—has, after forty years at the Post Office, to be contented on retirement with no more than the modest pension due to him, which will not even be continued to his nearest and dearest relative.

Allen benefited the Bristol postal district in another way than by his improved Post Office services when he built the bridge over the Avon at Newton-St.-Loe at a cost of £4,000. He was buried in Claverton Churchyard, near Bath. The inscription on his tomb runs thus:—"Beneath this Monument lieth entombed the Body of Ralph Allen, Esqr., of Prior Park, who departed this life ye 29th day of June, 1764, in the 71st year of his Age. In full hope of everlasting happiness in another state thro' the infinite merit and mediation of our blessed Redeemer, Jesus Christ."

Ralph Allen did not hoard up his money or spend it on riotous living, but bestowed a considerable portion of his income in works of charity, [Pg 15] especially in supporting needy men of letters. He was a great friend and benefactor of Fielding, and in Tom Jones the novelist has gratefully drawn Mr. Allen's character in the person of Squire Alworthy. He enjoyed the friendship of Chatham and Pitt; and Pope, Warburton, and other men of literary distinction were his familiar companions. Pope has celebrated one of his principal virtues—unassuming benevolence—in the well-known lines:

Derrick has thus described Allen's personal appearance shortly before his death: "He is a very grave, well-looking man, plain in his dress, resembling that of a Quaker, and courteous in his behaviour. I suppose he cannot be much under seventy. His wife is low, with grey hair, and of a very pleasing address." Kilvert says that he was rather above the middle size and stoutly built, and that he was not altogether averse to a little state, as he often used to drive into Bath in a coach and four. His handwriting was very curious; he evidently wrote quickly and fluently, but it was so [Pg 16] overloaded with curls and flourishes as to be sometimes scarcely legible.

The lack of all show about his garb seems to have somewhat annoyed Philip Thicknesse, the well-known author of one of the Bath Guides, for he speaks of Allen's "plain linen shirt-sleeves, with only a chitterling up the slit."

Allen's son Philip became Comptroller of the "By-Letter" Department in the London Post Office.

Ralph Allen's Tomb in Claverton Churchyard, near Bath.

Ralph Allen's Tomb in Claverton Churchyard, near Bath.Notwithstanding Ralph Allen's innovations, the conveyance of letters between the principal towns was carried on in a more or less desultory fashion. Speaking of the want of improvement in 1770, and the haphazard system under which Post Office business was conducted, a local newspaper gave this instance of unpunctuality: "The London Mail did not arrive so soon by several hours as usual on Monday, owing to the mailman getting a little intoxicated on his way between Newbury and Marlborough, and falling from his horse into a hedge, where he was found asleep, by means of his dog." Mr. Weeks, who entered upon "The Bush," Bristol, in 1772, after ineffectually urging the proprietors to quicken their speed, started a one day coach to Birmingham himself, and carried it on against a bitter opposition, charging the passengers [Pg 18] only 10s. 6d. and 8s. 6d. for inside and outside seats respectively, and giving each one of them a dinner and a pint of wine at Gloucester into the bargain. After two years' struggle his opponents gave in, and one day journeys to Birmingham became the established rule.

John Palmer.

John Palmer.The mail service was carried on chiefly by means of postboys (generally wizened old men), who continued to travel on worn-out horses not able to get along at a speed of more than four miles an hour on the bad roads. On the London and Bristol route, indeed, it had been found necessary to provide the postboys with light carts, but that method of conveyance of the mail bags brought about no acceleration in time of transit,—from thirty to forty hours, according to the state of the roads. A letter despatched from Bristol or Bath on Monday was not delivered in London until Wednesday morning. On the other hand a letter confided to the stage coach of Monday reached its destination on Tuesday morning, and the consequence was that Bristol traders and others sent letters of value or urgency by the stage coach, although the proprietors charged 2s. for each missive. [Pg 19]

At this period John Palmer, of Bath, came on the scene. He had learnt from the merchants of Bristol what a boon it would be if they could get their letters conveyed to London in fourteen or fifteen hours, instead of three days. It is said, however, that it was the sight of Ralph Allen's grand place at Prior Park, and the knowledge of how Allen's money had been made, which first suggested to Palmer the attempt to bring a scheme for a mail coach system to the notice of the postal authorities. John Palmer was lessee and manager of the Bath and Bristol theatres, and went about beating up actors, actresses and companies in postchaises, and he thought letters should be carried at the same pace at which it was possible to travel in a chaise. He devised a scheme, and Pitt, the Prime Minister of the day, who warmly approved the idea, decided that the plan should have a trial and that the first mail coach should run between London and Bristol. On Saturday, the 31st July, 1784, an agreement was signed in connection with Palmer's scheme under which, in consideration of payment of 3d. a mile, five inn-holders—one belonging to London, one to Thatcham, one to [Pg 20] Marlborough, and two to Bath—undertook to provide the horses, and on Monday, the 2nd August, 1784, the first "mail coach" started. On its first journey it ran from Bristol,—not from London as generally supposed,—and Palmer was present to see it off. A well-armed mail guard in uniform was in charge of the vehicle, which was timed to perform the journey from Bristol to London in sixteen hours. Only four passengers were at first carried by each "machine," and the fare was £1 8s. The immediate effect was to accelerate the delivery of letters by a day. The coaches were small, light vehicles, drawn by a pair of horses only, but leaders were subsequently added, and four-horse coaches soon became the order of the day, and more passengers were carried. An old painting represents the Bath and Bristol mail trotting along close to a wall, the guard receiving one bag and handing another to the postmaster without the coachman pulling up. One coach left Bristol at 4.0 in the afternoon, reached Bath a couple of hours later, and arrived at the General Post Office, London, before 8.0 the next morning. The down coach started from London at 8.0 in the evening, was at the "Three Tuns," Bath, at a few minutes before [Pg 21] 10.0 the next morning, and pulled up at the "Rummer Tavern," Bristol, at noon. Palmer gave up his theatrical enterprises and entered the service of the Post Office as Comptroller at a salary of £1,500 a year, and certain emoluments, which, after a year or two, brought him in an annual sum of more than £3,000. Before Palmer's mail coaches were at work the post left London at all hours of the night, but it was part of his scheme that the mails should all leave at the same time, 8.0; and as the number of mails increased so there was more and more bustle in the vicinity of the General Post Office at that hour. In London the arrival of all the mails was awaited before any one of them was delivered; and this led to the delivery sometimes not taking place until 3.0 or 4.0 in the afternoon, or even later. Palmer, with his regard for the Bristol coach, occasionally had the Bristol mails distributed immediately on reaching St. Martin's-le-Grand, but all other mails if behind were kept waiting as before.

Old English "Flying" Mail Coach.

Old English "Flying" Mail Coach.

Upon the beginning of Palmer's system on the Bristol road a marvellous superstructure was raised. Coaches were at once applied for by the municipalities [Pg 22] of the largest towns, Liverpool being the first to aim at equality with Bristol, and York claiming what was due to the great highway to the North. Palmer's plan made rapid progress and was attended with complete success. A splendid mail service was eventually set up all over the country. One result was that the "expresses" to Bristol, which before had been as many as two hundred in the year, ceased altogether. In July, 1787, the mails from Bristol to Birmingham and the North, previously three per week, were ordered to be run daily. The London to Bristol coach was stopped by other means than those employed by highwaymen, the service having at one time in 1790 been suspended for several days by Palmer, in defiance of the Postmaster-General.

In Bonner and Middleton's (weekly) Journal for the 11th February, 1792, is an announcement to the effect that the Irish mails arrived in Bristol on the 6th instant instead of on the first of the month. The bare fact was stated, and the assumption is, therefore, that it was not an unusual circumstance. Five days' delay would be thought intolerable now, as, indeed, is the present length of time occupied by the Irish [Pg 23] night mails on their journey to Bristol. After being conveyed by fast boat to Holyhead and express train to Birmingham, they come on from that city by a "crawler" and do not reach Bristol until nearly the mid-day hour.

In the same year (1792) sixteen mail coaches worked in and out of London every day. There were fifteen cross-country mail coaches, as, for instance, the coach between Bristol and Oxford, or, as it was commonly called, Mr. Pickwick's coach. During winter, in frosty weather, at this period, some of the mail coaches did not run at all, but were laid up for the season, like ships during Arctic frosts.

There is a model of an old mail coach at the General Post Office, St. Martin's-le-Grand, London, popularly supposed to be the model of the first mail coach which was built, but such is not the case, for, as already stated, the first mail coach ran between Bristol and London, and the model has upon it the inscription "Royal Mail from London to Liverpool."

The expense of horsing a four-horsed coach running at the speed of from nine to ten miles an [Pg 24] hour was reckoned at £3 a double mile. Mails were exempt from turnpike tolls.

With the introduction of the mail coaches with well-armed, resolute guards, there was a cessation of mail robberies on the main roads. Pilfering, however, was occasionally carried on; for instance, in the early winter of 1794 one Thomas Thomas travelled day after day up and down on the London and Bristol coach. At last his opportunity came when the guard temporarily left his coach with the mailbox unlocked, and then Thomas Thomas looted the mails. On the cross roads the saddle horse and cart posts were frequently stopped and robbed (1796). One of the worst roads in this respect was that between Bristol and Portsmouth. Proposals for the postboys to be furnished with pistols, cutlasses, and caps lined with metal, like hunting caps, for the defence of the head, fell through on account of the expense which their supply would have entailed.

There exists a popular belief that the mail coaches were driven up and down the steep Queen Street in Bristol now known as Christmas Steps. The belief is erroneous, for an inscription over [Pg 25] the recessed seats at the top of the passage tells us that—

Probably, however, the postboys who carried the mails in earlier days rode up the steep incline.

A gentleman now writing in the Bristol Times and Mirror under the nom-de-plume of "Old File," delving in the historical garden of Felix Farley's Journal, has unearthed the following very interesting announcements and advertisements, which throw light on the mail services of the time:—

"MILFORD AND BRECKNOCK MAIL COACH.

"A coach sets out from the 'White Hart,' Broad

Street, Bristol, over the Old Passage (Aust), every

Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday, at noon, and joins

the above coach at Ragland the same day; and a

corresponding coach returns from Milford on certain

days." The chief point in the advertisement was

in the paragraph: "N.B.—This road is nineteen

[Pg 26]

miles nearer to Carmarthen and Milford than the

lower one," that is, by the New Passage.

This was replied to by another advertisement, as follows:

"A Caution.—The public will please to observe

that no other mail coach whatever does now, or ever

has, run from Bristol to Milford Haven, excepting

the Royal London, Bath, Bristol, and Milford Haven

mail coach, which sets out from the 'Bush Inn

and Tavern,' Corn Street, every Monday, Tuesday,

Thursday, and Saturday, and the mail coach to

Swansea every day from the same inn, notwithstanding

the flaming advertisement of a certain set

of men to deceive and mislead the public, by their

asserting that the road over the Old Passage is

nineteen miles nearer than that over the New

Passage, which is so far from being a fact that

the road of the New Passage is seven and three-quarters

nearer, as was proved by admeasurement

by orders of the office, making a difference of

twenty-six miles and three-quarters nearer the

lower (that is, the New Passage) than the upper

road."

On August 4th the proprietors of the New Passage [Pg 27] coach came out with a larger announcement, and produced figures to prove their assertion—

"N.B.—This road is nineteen miles nearer to Milford than the lower one, viz:—

UPPER ROAD. | LOWER ROAD.

Miles. | Miles.

Old Passage 11 | New Passage 10

Across the Water 1 | Across the Water 3

Ragland 14 | Newport 15

Abergavenny 9 | Cardiff 12

Brecknock 19 | Cowbridge 12

Trecastle 10 | Pill 12

Llandovery 9 | Neath 13

Llandilo 12 | Ponterdilas 10

Carmarthen 15 | Kidwelly 14

St. Clare's 9 | Carmarthen 9

Narberth 13 | St. Clare's 9

Haverford-West 10 | Narberth 13

Milford 10 | Haverford-West 10

| Milford 10

--- | ---

Total 142 | Total 161

In favour of the Upper Road, 19 miles."

"Bristol, 4th January, 1799.

"Lost, on Monday morning, small letter-bag,

marked on it 'Worcester and Bristol.' Whoever

has found the same shall, on delivering it at the

Post Office, receive five guineas reward; and whoever

detains it after this notice will be prosecuted."

[Pg 28]

"General Post Office,

Friday, 15th February, 1799.

"George Evans, of Steep Street, St. Michael's, in the City of Bristol, Grocer, having been committed to the Gaol of Newgate, in the said City, charged with feloniously negotiating two Bills of Exchange contained in the bag of letters from Worcester for Bristol of the 30th December last, which was lost or stolen, and there being great reason to believe that one or more person or persons is or are privy to or concerned with him in the said felony: Whoever will give information at the Council Chamber in Bristol within one month from the date hereof, so that the said George Evans may be convicted of the offence with which he is charged, shall be entitled to a reward of fifty pounds. And if an accomplice shall make discovery he will also receive His Majesty's most gracious pardon.

"By command of the Postmaster-General.

"Francis Freeling, Secretary."

June 29th, 1799.

"We understand that a bill for £50, drawn by

the Worcester Bank on Messrs. Harfords, Davis

[Pg 29]

and Co., of this City, and which was one of the

bills contained in the Worcester bag lost on the

31st December last, has been presented within

these few days for payment—a circumstance which

may probably lead to the discovery of the party

who found the said bag."

August 10th.

"Last week George Evans, who was tried at the

Old Bailey in June last on a charge of forging

endorsements on two bills (which, with many

others, were contained in the Worcester bag

destined for this City that was lost on the 21st

December last, and of which intelligence has since

been obtained), but who was acquitted for want of

sufficient evidence, was again apprehended, and was

committed to gaol on a charge of having stolen a

promissory note, drawn by Messrs. Harfords, Davis

and Co., of this City, value fifty pounds, which note

was likewise sent by the same conveyance from

Worcester, and being attempted to be negotiated,

was stopped and traced back into the hands of the

said Evans, against whom a detainer was lodged

on account of a similar charge for another bill of

[Pg 30]

the same value, and precisely under all the circumstances

attending the former."

"General Post Office,

"October 11th, 1798.

"The postboy carrying the mail from Bristol to Salisbury on the 9th instant was stopped between the hours of eleven and twelve o'clock at night by two men on foot within six miles of Salisbury, who robbed him of seven shillings in money, but did not offer to take the mail. Whoever shall apprehend the convict, or cause to be apprehended and convicted both or either of the persons who committed this robbery, will be entitled to a reward of fifty pounds over and above the reward given by Act of Parliament for apprehending highwaymen. If either party will surrender himself and discover his accomplice he will be admitted as evidence for the Crown, receive His Majesty's most gracious pardon, and be entitled to the said reward.

"By command of the Postmaster-General.

"Francis Freeling, Secretary."

There is no record that anyone claimed the reward.

This, so far, is the end of "Old File's" researches. [Pg 31]

As the Bristol mail coach was going through Reading on the night of Thursday, the 18th January, 1799, the coachman was shook off the box, and, through his hands having been so benumbed by the cold, was unable to save himself. The guard jumped down and endeavoured to stop the horses, but without effect. They ran as far as Hare Hatch (four miles), where the coach changed horses, and then stopped, having met with no accident whatever, though they passed two wagons. The passengers in the coach did not know anything of it at the time.

According to the Bristol Directory for 1811, the "Bush Tavern" office in Corn Street, conducted by John Townsend, played an important part in the mail coach system of the country. Its announcement ran thus: "Royal mail coach to London at 4.0 every afternoon; comes in at half-past 11 every morning. 'Loyal Volunteer' to London at 12.0 every day. Royal mail coach to Newport, Cardiff, Cowbridge, Neath, Swansea, and Carmarthen every day on the arrival of the London mail. Royal mail coach through Newport, Cardiff, Cowbridge, Swansea, Carmarthen, to Haverfordwest and Milford [Pg 32] Haven every Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday on the arrival of the London mail. The 'Cambrian,' a light post coach, the same route as the mail, to Swansea every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday morning at 6 o'clock; returns every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday evenings.

"Royal mail coach to Birmingham through Gloster, Tewkesbury, Worcester and Bromsgrove every evening at 7.0; comes in every morning at 6.0. A post coach to Birmingham every day. Royal mail coach through Bath to Tetbury, Cirencester, and Oxford, every morning at quarter-past 7, comes in at 6.0 every evening. Royal mail coach through Bath, Warminster, and Salisbury to Southampton and Portsmouth at 3.0 every day; comes in at 10.0 in the morning. Coach to Salisbury, Romsey, Southampton, and Gosport every day at 5.0 (Saturdays excepted), comes in at half-past 10.0 at night. Exeter, Original 'Duke of York' coach, through Bridgwater, Taunton, Wellington, and Cullompton every Tuesday, Thursday."

In 1813 the London to Bristol mail coach was robbed of the Bankers' parcel, value £2,000 or upwards. This was made known in the form of a [Pg 33] warning to the mail guards who travelled in charge of the Post Office bags. When in 1813-14 the great frost occurred, the Bristol mail coaches were obstructed by the heavy snowdrifts on the roads, and they came in day after day drawn by six horses each when they could struggle into the City.

The literature of the period yields nothing of interest again for some time.

The "Bristol Guide" in 1815 stated that—"Bristow is the richest city of almost all the cities of this country, receiving merchandize from neighbouring and foreign places with the ships under sail." And again, "Bristow is full of ships from Ireland, Norway and every part of Europe, which brought hither great commerce and large foreign wealth." There was no mention of their carrying mails.

The year 1818 is memorable in postal annals as that in which John Palmer died. His decease took place at Brighton, but not before he had lived long enough to see mail coaches splendidly turned out. Palmer, on the conclusion of his connection with the Post Office, was awarded a pension of £3,000 a year, equal to his full salary, which sum he [Pg 34] declared did not represent the amount of his salary and emoluments. Further difficulties ensued, and his son, Colonel Palmer, fought his father's battles right manfully in the House, and eventually, in 1813, the Government gave John Palmer a sum of £50,000.

In recognition of Palmer's great invention, the Chamber of Commerce of Glasgow not only made him an honorary member, but voted him fifty guineas for a piece of plate. The fifty guineas was spent on a silver cup, which bore the following inscription:—

TO

JOHN PALMER, Esq.,

SURVEYOR AND COMPTROLLER-GENERAL

OF THE POSTS OF GREAT BRITAIN,

FROM

THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

AND MANUFACTURERS

IN THE CITY OF GLASGOW,

AS AN ACKNOWLEDGMENT

OF THE BENEFITS

RESULTING FROM HIS PLAN

TO THE

TRADE AND COMMERCE

OF THIS KINGDOM,

1789.

To John Palmer, Esq., Surveyor and Comptroller-General of the Post Office

this Plate of the Mail Coach is respectfully inscribed

by his obedient humble servant, James Fittler.

To John Palmer, Esq., Surveyor and Comptroller-General of the Post Office

this Plate of the Mail Coach is respectfully inscribed

by his obedient humble servant, James Fittler.

A new coach, from "The Bush Hotel" to Exeter, was put on the road on the 6th of April, 1819, the time allowed for the journey—74¾ miles—being fourteen hours—less than 5½ miles an hour. In June, 1820 a new coach started for Manchester, performing the journey in two days, the intervening night being spent at Birmingham. To accomplish the first half of the task, the vehicle left Bristol at half-past 8 in the morning and reached Birmingham—85½ miles—in thirteen hours. An advertisement, published in December, 1821, headed "Speed Increased," informed the public that the "Regulator" coach left London daily at 5 a.m. and arrived at the "White Hart," Bristol, at five minutes before 9 at night, the speed being barely seven miles an hour. [Pg 36]

No fewer than twenty-two coaches were by this time utilised daily between this city and London. The start of the West Country mail coaches from Piccadilly at this period was an interesting sight. The continued wretched condition of the highways was not conducive to quick travelling; but in about 1825 matters were improved in that respect in our district by Mr. John Loudon MacAdam, who studied and practised road-making. Mr. MacAdam was general surveyor of Bristol turnpike roads, and although he found the trustees' funds only one remove from bankruptcy and their roads almost impassable, he succeeded so well that the finances flourished, and his highways became an object lesson to the world. Mr. Latimer, the Bristol historian, mentions that although MacAdam was shabbily treated by members of the old unreformed Corporation, and had many opponents, Bristol deserves the credit of being the first to appreciate the value of his labours, which were recognised later by a Parliamentary grant. He left Bristol for London, and died in 1836; but his son became surveyor of the Bristol roads, and continued to hold the appointment till his death in 1857.

The West Country Mail Coaches about to leave Piccadilly

with "Go Cart," Bringing up Late Mails

from the G.P.O.

The West Country Mail Coaches about to leave Piccadilly

with "Go Cart," Bringing up Late Mails

from the G.P.O.

The Gentlemen's Magazine, November, 1827, announced: "A Steam Coach Company are now making arrangements for stopping places on the line of road, between London, Bath and Bristol, which will occur every six or seven miles, where fresh fuel and water are to be supplied. There are fifteen coaches built." The Turnpike Trustees, who imposed extraordinary tolls on steam carriages, frustrated this scheme; but the threatened competition stirred up the coach proprietors, who increased the speed of their vehicles from the jog-trot of six or seven miles an hour, although not to such an extent as desired by the Bristol Chamber of Commerce, which in this year made a suggestion to the Post Office for bringing the London mail to the city in twelve hours. The Postmaster-General was also memorialised to accelerate the arrival of the West mail, so as to effect its delivery before the departure of the London mail,—a convenience of no little moment to the West India trade of the port, since it was thought that it would save one day in the conduct of business with the metropolis. At a general meeting in January, 1828, it was announced that the president had a conference on the subject [Pg 38] with the leading officer of the Post Office Department, with the result that the latter proposed alterations which were carried out, and were held to be proofs of the Postmaster-General's disposition to consult the accommodation of the Bristol public. The former proposal was not adopted at the time, for at the Accession of his late Majesty King William IV. (1830) the London mail coach took 13 hours 37 minutes on its journey viâ Reading. It departed at 8 p.m., reached Bath 8.11 a.m., and arrived in Bristol at 9.37 a.m., leaving again at 5.50 p.m. for the G.P.O. The Bristol and Brighton coach (138 miles) was bound to a speed of 10.4 miles per hour.

In January, 1830, there were further Post Office matters on the agenda of the Chamber of Commerce, for it was resolved—"That this meeting recommends to the Board the instituting an enquiry into the exact distance between the Post Office of London and Bristol, with a view to ascertain whether the rate of postage at present demanded is correct." The enquiry was prosecuted with vigour, for at the January annual meeting in the following year reference was made to the Turnpike Commissioners [Pg 39] for the several districts on the line of road between London and Bristol having supplied a statement of the precise extent of ground over which the mail coach travelled, comprised in their respective trusts. In several instances measurements were expressly made. In the result it appeared that the route exceeded in distance 120 miles, and the Post Office Department was therefore entitled legally to obtain the rate of 10d. per letter as the amount fixed by the provisions of the Act of Parliament. It was thought by taking the route from Chippenham through Marshfield instead of Bath the distance would be considerably shorter, and consequently bring about a reduced rate of postage. It was reported in the next year (January, 1832) that the requisition for changing the route had been pursued, and the president held a conference with Sir F. Freeling on the subject; but though every due consideration was promised, the alteration had not yet been acceded to. There was the significant addition that the application would nevertheless be renewed. A new royal mail direct from Bristol to Liverpool was established in 1831, leaving the "White Lion," Broad Street, Bristol, at 5.0 p.m., reaching Liverpool [Pg 40] at twenty minutes past 12 a.m. The new service was notified to Mr. Samuel Harford, the President of the Commerce Chamber, by Sir Francis Freeling, in the following terms:—

"G.P.O., 27th August, 1831.

"Sir,—Having brought under consideration the memorial from the Board of Directors of the Chamber of Commerce of Bristol, and from the bankers, merchants, and other inhabitants of Liverpool, transmitted in your letter of the 2nd May last, I have the satisfaction to acquaint you that His Grace the Postmaster General (Duke of Richmond) has consented to try the experiment of a mail coach between those towns, through Chepstow, Hereford, and Monmouth, and I flatter myself that it may commence about the middle of next month.

"I have the honour to be, Sir,

Your most obedient Servant,

F. Freeling, Secretary.

"Samuel Harford, Esq."

In the next year the Chamber learnt with satisfaction that the direct Liverpool mail through [Pg 41] Chepstow, Monmouth, Hereford, Shrewsbury and Chester, which was started as an experiment, had been continued, to the decided advantage of the public, particularly to all connected with the line of country through which it passed. As compared with the former route, the saving of time was equal to one day; the rate of postage was likewise reduced. The starting and arriving were at the most convenient hours the distance and circumstances, with reference to the passage of the two rivers, Severn and Medway, would permit. The coach had to run over the flat parts of the ground at a great pace, to make up for time lost at the hills. The contract time was 9 miles 2 furlongs in the hour.

One of the chief mail coaches in the kingdom in 1837 was the Bristol, Carmarthen and Milford (150 miles viâ Passage, one hour allowed for ferry), Cardiff and Swansea. Its down journey occupied 19 hours 38 minutes, and its up journey 20 hours.

The Liverpool and Milford mails were conveyed across the Severn at Aust Passage, where the ferry had been located since the Lord Protector's time. A moderate expenditure on the piers at Aust Passage, though little regarded by the citizens at [Pg 42] the time the work was in progress, with the introduction there of a steam vessel, was one of the principal means of bringing about the establishment of the additional communication with the districts over the Severn, the uncertainty and inconvenience of crossing its estuary being then to a large extent removed.

Mr. Oliver Norris, now nearly 80 years of age, and who has lived in the district adjoining the Severn Tunnel from his boyhood, can call to mind the time when the Liverpool and Milford coaches were running. They had to make their way from Pilning through Northwick, up to the Old Passage at Aust, and in rough weather the passengers must have had a cold ride on the bleak river banks over which they had to journey. When the Bristol and South Wales Railway was opened in 1863, the Aust Passage was abandoned, and the ferry steamers commenced to cross from the revived New (or Pilning) Passage, to connect with the new train services at Portskewet. When the penny post was introduced, Mr. Morris says that as the coaches passed through the villages the inhabitants in his district adopted a primitive way of posting their [Pg 43] letters, which was to place the letter and penny in a cleft stick, and so hand up to the mail guard as the coach was driven by, and who, if the penny was not forthcoming, promptly threw the letter to the ground.

The mail coach system was attended with many adventures. Mr. Moses James Nobbs, the last of the mail coach guards, recounted in the history of his career how, in the winter of 1836, when guard of the Bristol to Portsmouth coach, there were terrible snow-storms towards Christmas time, and many parts of the country were completely blocked. After leaving Bristol one night at 7 p.m. all went well until the coach was nearing Salisbury, at about midnight. Snow had been falling gently for some time before, but after leaving Salisbury it came down so thick and lay so deep that the coach had to be brought to a standstill, and could proceed no further. Consequently Nobbs had to leave the coach and go on horseback to the next changing place, where he took a fresh horse and started for Southampton. There he procured a chaise and pair, and continued his journey to Portsmouth, arriving there about 6 p.m. the next day. He was [Pg 44] then ordered to go back to Bristol. On reaching Southampton on his return journey the snow had got much deeper, and at Salisbury he found that the London mails had arrived, but could not go any further, the snow being so very deep. Not to be beaten, he took a horse out of the stable, slung the mail bags over his back, and pushed on for Bristol, where he arrived next day, after much wandering through fields, up and down lanes, and across country—all one dreary expanse of snow. By this time he was about ready for a rest. But there was no rest for him in Bristol, for he was ordered by the mail inspector to take the mails on to Birmingham, as there was no other mail guard available. At last he arrived at Birmingham, having been on duty for two nights and days continuously without taking his clothes off. For his exertions and perseverance in getting the mails through Mr. Nobbs received a special commendation from the Postmaster-General.

Moses Nobbs.

Moses Nobbs.Mr. Nobbs tells that one night when the Bristol coach was between Bath and Warminster, two men jumped out of the hedge; one caught hold of the leaders, and the other the wheelers, and tried to stop [Pg 45] the coach. The coachman, immediately whipped up the horses, and called out, "Look out! we are going to be robbed!" Mr. Nobbs took the blunderbuss out of the arms case (which was a box just in front of the guard's seat); but, just as he did so, he saw the fellows making towards the hedge, and then lost sight of them altogether. To let them know that he was prepared, he fired off into the hedge. He didn't know whether he hit anything, but he heard no cries or groans. The recoil of the blunderbuss, however, nearly knocked him off his seat. The blunderbuss, he said, kicked like a mule. It had no doubt been loaded to the muzzle, as was usual with those weapons. In the memorable storm of Christmas, 1836, alluded to by Mr. Nobbs, the Bath and Bristol mail coach, due in London on Tuesday morning, was abandoned eighty miles from the metropolis, and the mails taken up in a post-chaise and four by the two guards, who reached St. Martin's-le-Grand at 6.0 on the Wednesday morning. For seventeen miles of the distance the guards had from time to time to go across the fields to get past the deep snowdrifts.

In the annual procession of mail coaches round [Pg 46] London, at the head thereof was "the oldest established mail,"—the Bristol mail, probably with Guard Nobbs in charge. Some twenty-seven to thirty coaches took part in the procession thus headed. The old mail guards had a literature of their own. As an example, one report on a guard's way-bill ran as follows (it was a note to account for loss of time on North Road):—"As we wos comin' over Brumsgroove Lickey won of the leaders fell, and wen we com to him he was ded."

One old fellow used to laugh, as the men said, down in his boots, or like a pump losing its water. Another used facetiously to say that he had better than a dozen children. "Oh, Mr. ——," said a barmaid to him one day, "what can you do with so many?" "Well, my dear," he replied, "you see I've got but two, and they be, you must confess, a good deal better than a dozen."

It is said that, with the exception of a single instance, no guard was ever convicted of a breach of trust while performing his duties.

In the year of Her Majesty's accession (1837) there were no fewer than twenty-seven coaches running daily between Bristol and London, and [Pg 47] twenty-seven others passed between this city and Bath every twenty-four hours. The times of the London coach were as follow: London depart 8.0 p.m., Bath 7.21 a.m., Bristol arrive 8.43 a.m., depart 6.15 p.m., arrive G.P.O. 6.58 a.m.,—a slight acceleration over 1830.

Where now is the fashionable roadside "Ostrich Inn" on Durdham Down of a century ago, approached by a rough and winding track from Black Boy Hill? At this inn the coaches called on their way to the Passage. Where now are the old four-horsed coaches rattling up to "The Bush," "White Hart," and "White Lion" hostelries, and the old jolly dozen-caped coachmen and scarlet-liveried mail guards, with blunderbuss and horn? Where now the Bath and Bristol mail pulling up at the roadside "King's Head Inn"? The inns are gone, the coaches gone, the jolly guards all gone too. What happiness their smiling faces brought to many who watched for their arrival by the mail coach from the West of England, and how gladdening the sight of their colonial mail bags to the merchants of the city and to the sailors' wives looking out anxiously for the monthly mail of those days! Though single-sheet [Pg 48] letters cost 2s. 1d. each, what of that? Did they not contain accounts of sugar and rum cargoes, and of good news from absent ones. Letters were letters in those days, and not the notes and cards and "flimsies" of to-day.

Arrival of the Bath and Bristol Mail Coach at a Roadside Inn.

Arrival of the Bath and Bristol Mail Coach at a Roadside Inn.

Although the world's railway system was inaugurated by the opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825, it was not until 1838 that any attempt was made by a great railway to open up the traffic to the West from the Metropolis. It was in that year that the Great Western Company made a line between Paddington and Maidenhead, and mails were sent by it. The section from Bristol to Bath was opened in the same year. Woolmer's Gazette of January, 1840, speaks of the 9.0 a.m. "Exquisite" coach for Bristol, Cheltenham, Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool, with part of the service by rail. Intermediate sections of the railway were completed from time to time, and, finally, on the 30th January, 1841, the Western line was opened throughout, and the coaches which [Pg 50] had formed so striking a feature both of town and country life generally disappeared. One coach, however, obstinately held its ground in spite of the railway, and continued to carry passengers from and to London and Bristol at the rate of 1d. per mile until October, 1843.

In consequence of the completion of the Great Western Railway to Bristol, extensive mail alterations had to be made, and they were commenced on the 30th July, 1841, affecting the whole district right through Somersetshire and Devonshire into Cornwall. Some towns were made post towns and others were reduced from the rank of post towns to that of sub-post offices. To meet the altered circumstances, revised sacking of bags had to be resorted to. The instructions given by the President to the staff in St. Martin's-le-Grand ended thus:

".... Any bags in addition to the ordinary number must be reported to the road officers by the clerks of the divisions, that they may be entered under the head of 'extra,' also any agents or portmanteaus for Falmouth; and they must instruct the men carrying out the sacks and bags first to report them to the check clerk, and then take them through [Pg 51] the letter carriers' office to the Devonport or Gloucester omnibus, as the case may be, as the guards will not for the future come into the office."

It was at this time that the villages of Hallatrow, High Littleton, Paulton, Harptree (East and West), Farrington Gurney, Temple Cloud, Cameley, and Hinton Blewett were transferred from the postal control of Bath to that of Bristol, under which they still remain.

For several years the only trains carrying third-class passengers from Bristol started at 4.0 o'clock in the morning and 9.0 o'clock at night, offering the travellers, who were wholly unprotected from the weather, an alternative of miseries, and at first travellers were not much better off in point of speed when travelling by railway, as third-class passengers were 91⁄2 hours on the railway between Bristol and London. The coach at the time of its being taken off performed the journey under 12 hours.

The "Bush" coach office was closed in March, 1844.

The Bristol and Gloucester Railway was opened to the public on the 8th July, 1844. Of the seven coaches which had been running between the two [Pg 52] cities six were immediately withdrawn, and on the 22nd July the time-honoured "North Mail" left Bristol for the last time, the horses' heads surmounted with funereal plumes and the coachman and guard in equally lugubrious array.

As late as 1845 Her Majesty's mails were conveyed between Bristol and Southampton in a closed covered cart, "proper for the purpose," as set forth in an advertisement inviting tenders for a new contract. The whole journey had to be performed at the rate of eight miles within the hour, stoppages included. The hours of despatch were: From Bristol at about 6.0 p.m., and from Southampton about 9.0 p.m.

"The Old Bush Hotel," Corn Street, Bristol.

"The Old Bush Hotel," Corn Street, Bristol.In 1849 a great mail robbery took place, which was committed with very much daring. The robbers, who booked from Starcross station on the 1st January, left a compartment of the up night mail train (which left Bridgwater at 10.30 p.m. and reached Bristol at midnight); they crept along the ledge, only 1½ inch wide, to the mail-brake at the rear of the post office sorting carriage, and effected an entrance, having previously possessed themselves of a key of the lock. After having rifled the mail [Pg 53] bags they crept back to their compartment, and alighted from the train at the Bristol station, giving up their tickets to the Great Western Railway policeman. Not contented with robbing the up mail, they got into the night mail train from London to the West, which left Bristol at 1.15 a.m., and actually had the daring to pursue the same tactics with regard to the mail bags in the locked brake. This further audacity brought about their capture, for the news of the robbery of the up mail reached the ears of the officers at Bristol who were in the down mail, and so they were on the alert. On arrival, therefore, at Bridgwater the second robbery was at once detected, all exit from the station was stopped, and the train searched. Two men were discovered in a first-class compartment near the travelling post office, and registered letters and money letters were found upon them. In addition to the letters, masks, and false moustache found, a woolstapler's hook, which it is supposed was used by the thieves to hang on to the tender when leaving the first-class carriage, was also discovered. One of the registered letters stolen, it was stated, contained £4,000, and the loss, as far as it [Pg 54] was known, unquestionably amounted to fifty times that sum. The robbers turned out to be Henry Poole, a discharged Great Western guard, and Edward Nightingale, a London horse dealer. The case excited a great deal of interest in the West of England, and when the trial took place at Exeter the court was crowded to excess, and the avenues and approaches thereto were very inconveniently crowded. Mr. Rogers, Q.C., and Mr. Poulden appeared for the prosecution, and Mr. Slade, Mr. Cockburn, Q.C., and Mr. Stone defended.

Evidence was given by clerks in the Lombard Street Post Office, messengers and letter-carriers in the G.P.O., "register" clerks, clerk at Charing Cross Post Office, the clerk of the Devonport Road, guard of the mail from St. Martin's-le-Grand to Paddington, and by letter-sorters in the travelling Post Office. Jane Crabbe, barmaid at the "Talbot Inn," Bath Street, Bristol, recollected the two men entering the bar and calling for two small glasses of brandy-and-water. They were shown to an adjoining room, where they remained until 1 o'clock, and then went to the bar to pay. They appeared impatient, and looked at the clock. It was suspected that all the [Pg 55] property which, had been abstracted from the up mail was secreted somewhere in Bristol, and a most rigid search was instituted, but without success. Mr. Cockburn's speech to the jury for the defence occupied over two hours. Lord Justice Denman, the Judge of the Spring Assize, sentenced the culprits to fifteen years' transportation.

A Select Committee was appointed in 1854 to inquire into the causes of irregularity in the conveyance of mails by railways, and to consider the best means of securing speed and punctuality; also to consider the best mode of fixing the remuneration of the various Railway Companies for their services. The local witnesses, Mr. James Creswell Wall and Mr. J. B. Badham, Secretary and Superintendent respectively of the late Bristol and Exeter Railway Company, and Bristol residents, gave evidence before the Committee, composed of Mr. Wilson Patten (chairman), Mr. James MacGregor, Mr. H. G. Liddell, Mr. H. Herbert, Mr. C. Fortescue, Mr. Cowan, Mr. Thompson, Mr. Philipps, and Mr. Milner.

Replying to questions, witnesses considered two hours forty minutes, as fixed by the Post Office Department, insufficient time for the down night mail to [Pg 56] travel from Bristol to Exeter, including six stoppages. The delivery of mail bags at certain stations by apparatus without stopping the train was suggested, but witnesses considered the plan dangerous and that it could not with safety be adopted.

The Secretary of the South Wales Railway Company, Mr. F. G. Saunders, gave evidence as to the frequent loss of time sustained by the South Wales night mail through the late receipt of the Bristol and West of England mails at Chepstow. At that time the bags for South Wales were still conveyed from Bristol to the Aust Passage, thence by ferry to the opposite bank of the Severn and on to Chepstow. The conveyance of mails for South Wales viâ Gloucester was subsequently adopted.

All the witnesses complained of the reduction of railway parcel traffic through the then recent establishment of book postage and consequent falling off of receipts, also that the remuneration awarded for the carriage of mails was insufficient, although decided by mutually-appointed umpires.

The Old Passage, Aust.

The Old Passage, Aust.

For many years the night mails were conveyed between Paddington and Bristol by a special train, which did not carry passengers. It was the only [Pg 57] train of its kind in the kingdom, but so useful was it held to be in securing a regular delivery of letters that the Government introduced a clause in a Postal Bill in 1857 rendering it compulsory for all railways to provide similar trains. On the 1st June, 1869, the Post Office special Great Western train commenced to be a mail train limited to carry a certain number of passengers, so that opinion had by that time become altered as regards the value in relation to cost of a train exclusively for Post Office purposes.

The travelling Post Office service assists greatly in the speedy distribution of letters, and by its agency remote places are put on an equality with the country generally in respect of deliveries and despatches. Two of the most important travelling Post Office systems in the kingdom are conducted through, or to, Bristol—the gate to the Western country—viz.: The Great Western Railway, with a travelling Post Office annual mileage of 500,000; and the Midland and North-Eastern lines from Newcastle, with a mileage of 220,000. Travelling Post Offices, with a combined coach length of from 48 feet on the day mails to 158 feet on the night [Pg 58] mails, are attached to the Great Western down trains which arrive at Bristol at 12.13 a.m. and 8.48 a.m.; to the up trains, at 12.45 a.m. and 3.0 p.m.; to the trains leaving Bristol for the West at 6.15 a.m. and 12.9 p.m., and for the North at 7.40 p.m. The Midland travelling Post Office carriages are attached to the 5.40 a.m. inward train and to the 7.0 p.m. outward train.

There is living at Midford, about fifteen miles distant from Bristol, a gentleman (Mr. Coulcher) who—now pensioned from the Post Office—was the clerk in charge of the Midland Travelling Post Office on its first run from Bristol to Derby in 1857. He well recollects the night, and what impressed it upon his memory more than anything else was the fact that on reaching Bristol, after he and his two subordinate clerks and his mail-guard (Samuel Bennett) had made almost superhuman efforts to get the work completed, he had to send 13,000 letters unsorted into the Bristol Post Office, there to await despatch by day mails to towns in the West of England, instead of going at once in direct travelling Post Office bags by the connecting early morning train. [Pg 59]

Samuel Bennett, the old mail guard mentioned, and contemporary of Moses Nobbs, was frequently injured on road and rail. In 1847 he was much shaken when a Birmingham-to-Bath train by which he was travelling ran off the line. A few years later he nearly came to an untimely end, having been regarded as dead after being much knocked about when two trains between Bristol and Birmingham collided. On that occasion, after he recovered consciousness, he got together some of his mail bags and carried them on to Bristol.

The Gloucester Journal said of the occurrence:—"Samuel Bennett, the guard of the mail bags, appeared dead when found, and was dreadfully cut; but on recovering, he manifested great anxiety for the bags. When the special train arrived in which the wounded passengers were conveyed onward, Bennett, with great courage, determined to take the bags by this train, which was done."

And the Bristol Mercury wrote of him as follows:—"The mail guard, Samuel Bennett, was very much cut over the face and head, and bled profusely. Happily, he was not rendered long unconscious or disabled, and with a conscientious and self-denying [Pg 60] attention to duty not often met with, he refused any attention to his hurts until he had gathered up the mutilated letter bags and their contents, and made provision for bringing them on to this city."

In the Bristol district there is a railway Post Office apparatus station at Fishponds, on the Midland Railway, bags being deposited thereat by the train due at Bristol at 5.40 a.m., and taken up by the train ex Bristol at 7.0 p.m. On the Great Western Railway, the apparatus arrangement is in operation at Flax Bourton, Nailsea, Yatton, and Hewish, chiefly in connection with the 6.15 a.m. train ex Bristol. It rarely happens that any failures occur at Fishponds or Hewish, but vagaries of the apparatus are more frequent at Yatton. About once a year something or other goes wrong, the pouch usually being dropped and carried along by the train, with mutilation of the mail bags and a general scattering of the letters. On the last occasion, after the line had been searched up and down, the embankment closely looked over, and the ground on the other side of the hedge on the down side closely scrutinized, all unavailingly, some two or three days [Pg 61] after the accident a bundle of letters was picked up which, such was the force of the impact, had been "skied" into a field over two hedges of an intervening lane.

On another similar mishap, a Post Office remittance letter containing £20 in gold was burst open and the coins scattered over the line. After diligent search in every direction, £18 10s. was recovered. One half sovereign, bent in an extraordinary manner, was found between the metals three-quarters of a mile from the apparatus standard. The apparatus has to be adjusted with mathematical nicety, and if not so arranged failures are liable to occur. It is well that the public should bear in mind that packets sent by mails which are exchanged by apparatus are in more or less danger, and any article of a fragile or costly nature should, if possible, be forwarded by mails carried by stopping-trains. The places so affected in this neighbourhood are:—Alveston, Bitton, Blagdon, Burrington, Clevedon, Congresbury, Downend, Fishponds, Flax Bourton, Frampton Cotterell, Frenchay, Glastonbury, Hambrook, Hewish, Iron Acton, Langford, Mangotsfield, Nailsea, Oldlands Common, Portishead, Pucklechurch, [Pg 62] Rudgeway, Sandford, Staple Hill, Thornbury, Tockington, Warmley, West Town, Willsbridge, Winterbourne, Wrington, and Yatton.

Until lately mails for Bristol were forwarded by the midnight train from Euston (L. & N. W. R.) and reached this city by way of Birmingham in time for the North mail delivery. It was on that railway that in 1890 a sad occurrence happened at Watford, when a young man whilst in the discharge of his duties as fireman lost his life. The deceased was leaning over the side of his engine, which was stationary, watching for the signals to be turned, when the day mail train from London dashed by. The travelling Post Office apparatus net which had picked up a pouch at a point a few score yards away was still extended and it struck the unfortunate young man on the head, completely severing it from the body. The poor fellow's cap was torn from his head by the apparatus net and fell into the travelling Post Office carriages with the mail pouches much to the consternation of the travelling sorters, who found evidence of the mutilation on the apparatus framework. The net was only down for the short space of ten seconds. The travelling officials first heard [Pg 63] full details of the accident on their arrival at Tring, where the train next stopped.

"Once upon a time," writes Mr. A. W. Blake in the St. Martin's-le-Grand Magazine, "the London afternoon mail was made up at a provincial office down West (Chippenham), and despatched to be taken off by apparatus. All proceeded as usual up to the actual point of transfer, when a strange thing happened. Instead of falling soberly into the net, the man in charge was astonished to see the pouch leap high into the air and descend he knew not whither. Search was carefully made along the track of the departed train, but not a vestige of the missing pouch could be seen, and a local inspector who was travelling up the line promised to keep a look-out for it. Just at this time an 'S.G.' was received from the officer in charge of the sorting tender notifying the non-receipt of the pouch. As the mystery seemed to deepen, word was received that a signalman at a level crossing two miles away had noticed the missing article on the top of the train. Quoth the worthy apparatus man: 'If it'll ride two miles, it'll ride two hundred'; and accordingly a wire was sent to the sorting-tender people [Pg 64] asking them to search the top of the train, and soon came the reply that the pouch had been found on the roof of the guard's van at Didcot. The train had stopped the regulation time at that hub of the Great Way Round, Swindon, and proceeded on its way without the extraordinary position of Her Majesty's mails being discovered."

The occurrence was attributed to the swaying of the carriage, and to the apparatus-net not working quite steadily in consequence.

At a later period than the mishap narrated by Mr. Blake, the bags for Oxford and Abingdon, due to be picked up at Wantage by the up night mail travelling Post Office apparatus, and to have been delivered by the same process at Steventon, were not found when the net was drawn in, and it was thought they had been missed; but at Didcot it was discovered they had been thrown over the end of the net and were hanging outside it.

Since the opening of the Severn Tunnel in 1883 it has not often been found an absolute necessity to make use of it for the conveyance of mails diverted from the route from South Wales through Gloucester to London; but such was the case in February of [Pg 65] the present year (1899), when a tidal wave of forty feet was experienced in the Bristol Channel, which caused serious damage by displacing the railway line between Lydney and Wollaston. The effects of the high tide were disastrous. A wave dashed on to the Great Western Railway with huge force, and so disintegrated the ballasting of the permanent way that the lines were twisted into all manner of shapes. The mails to and from Paddington to South Wales were circulated viâ Bristol and the Tunnel for some time.

Bristol is at a disadvantage as compared with London in respect of its Continental correspondence, but is far better situated than many other provincial towns. The letters from the Continent by night mails reach Bristol by the train leaving London at 9.0 a.m. and, arriving at Temple Meads at 11.57 a.m., are on delivery in the private box renters' office at about 12.30 p.m. The postmen start out with the letters at 1.10 p.m. As the hour of posting for the outward Continental night mails is 2.10 p.m., it is only the private box renters who have time, brief though it be, to reply to their correspondence on the day of receiving it. [Pg 66]

An appeal to the Hon. Member for Bristol East was made by the writer at a Chamber of Commerce dinner to exercise his influence as a director of the Great Western Railway in the direction of obtaining the use of a goods train for the conveyance to Bristol of a midnight mail from London. In the end the Railway Company afforded the Post Office the means of bringing down a midnight mail, not by goods train as was originally contemplated, but by new and fast passenger train, with the result that half a million letters a year now fall into the first delivery throughout the town, instead of into the second delivery as heretofore. The letters posted in London up to 9.0 p.m. reach the head office in Small Street in time to be delivered throughout the city and suburbs by the postmen on their first round. Under the old system, when "routed" viâ Birmingham, the arrival was often so late and irregular that the letters missed even the second delivery. The letters for the rural districts having no day mail deliveries had to lie at Bristol for twenty-four hours, while now they are delivered on the morning of receipt from London. The advantages o£ the new system apply to parcels as well as letters, and the acceleration in delivery [Pg 67] is particularly serviceable as regards parcels containing perishable articles.

The Railway Company recently gave the Department another opportunity of improving the mail services by establishing a merchandise train from Cornwall and the West to London, reaching the Metropolis in time for the letters sent by it to be delivered some three or four hours earlier than when conveyed by the first passenger train in the morning. Strangely enough, the establishment of this new mail service was the means of enabling the hon. baronet (Sir W. H. Wills), the Member for Bristol East, to take his seat in the House of Commons on the day of his last election, for the writ and return were sent by that mail to London in time to reach the Crown Office for all formalities to be gone through in connection with the seat being taken at once.

Official records at St. Martin's-le-Grand show that postmasters of Bristol were appointed as follows; viz., Thomas Gale, 1678; Wm. Dickinson, 1690; Daniel Parker, 1693; Henry Pine, September, 1694; Thomas Pine, senior, 1740; Thomas Pine, junior, 16th January, 1760; William Fenn, 1778; Mrs. Fenn, 1788; Mr. Fry managed the office for Mrs. Penn from 1797 to December, 1805, when he died, and Mrs. Fenn retired on an allowance in 1806; Mr. Cole, March, 1806, died whilst holding office; John Gardiner, 9th June, 1825; Thomas Todd Walton, senior, 21st February, 1832; Thomas Todd Walton, junior, 23rd May, 1842, succeeded his father; Edward Chaddock Sampson, 21st June, 1871; Robert Charles Tombs, 19th April, 1892, after having been invalided from Controllership of the London postal service.

In his history of the Post Office, Mr. Joyce tells us that in 1686 the Postmaster-General himself [Pg 69] settled applications for salary. Thus when Thomas Gale, postmaster of Bristol, applies for an increase of salary, Frowde the governor satisfies the Earl of Rochester, the Postmaster-General, that the increase will be proper. Forthwith issues a document, of which the operative part is as follows:—