The Project Gutenberg EBook of Planet of the Gods, by Robert Moore Williams This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Planet of the Gods Author: Robert Moore Williams Release Date: June 5, 2010 [EBook #32696] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PLANET OF THE GODS *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

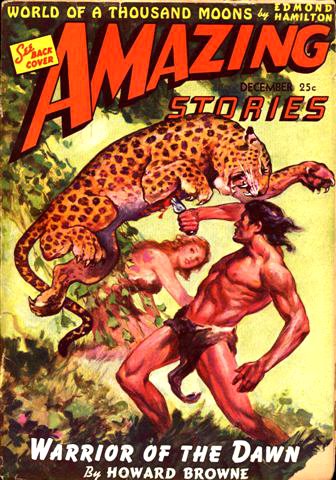

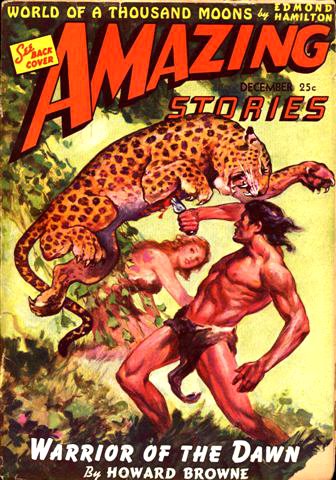

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Amazing Stories December 1942. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"What do you make of it?" Commander Jed Hargraves asked huskily.

Ron Val, busy at the telescope, was too excited to look up from the eye-piece. "There are at least two planets circling Vega!" he said quickly. "There may be other planets farther out, but I can see two plainly. And Jed, the nearest planet, the one we are approaching, has an atmosphere. The telescope reveals a blur that could only be caused by an atmosphere. And—Jed, this may seem so impossible you won't believe it—but I can see several large spots on the surface that are almost certainly lakes. They are not big enough to be called oceans or seas. But I am almost positive they are lakes!"

According to the preconceptions of astronomers, formed before they had a chance to go see for themselves, solar systems were supposed to be rare birds. Not every sun had a chance to give birth to planets. Not one sun in a thousand, maybe not one in a million; maybe, with the exception of Sol, not another one in the whole universe.

And here the first sun approached by the Third Interstellar Expedition was circled by planets!

The sight was enough to drive an astronomer insane.

Ron Val tore his eyes away from the telescope long enough to stare at Captain Hargraves. "Air and water on this planet!" he gasped. "Jed, do you realize what this may mean?"

Jed Hargraves grinned. His face was lean and brown, and the grin, spreading over it, relaxed a little from the tension that had been present for months.

"Easy, old man," he said, clapping Ron Val on the shoulder. "There is nothing to get so excited about."

"But a solar system—"

"We came from one."

"I know we did. But just the same, finding another will put our names in all the books on astronomy. They aren't the commonest things in the universe, you know. And to find one of the planets of this new system with air and water—Jed, where there is air and water there may be life!"

"There probably is. Life, in some form, seems to be everywhere. Remember we found spores being kicked around by light waves in the deepest depths of space. And Pluto, in our own system, has mosses and lichens that the biologists insist are alive. It won't be surprising if we find life out there." He gestured through the port at the world swimming through space toward them.

"I mean intelligent life," Ron Val corrected.

"Don't bet on it. The old boys had the idea they would find intelligent life on Mars, until they got there. Then they discovered that intelligent creatures had once lived on the Red Planet. Cities, canals, and stuff. But the people who had built the cities and canals had died of starvation long before humans got to Mars. So it isn't a good bet that we shall find intelligence here."

The astronomer's face drooped a little. But not for long. "That was true of Mars," he said. "But it isn't necessarily true here. And even if Mars was dead, Venus wasn't. Nor is Earth. If there is life on two of the planets of our own solar system, there may be life on one of the planets of Vega. Why not?" he challenged.

"Hey, wait a minute," Hargraves answered. "I'm not trying to start an argument."

"Why not?"

"If you mean why not an argument—"

"I mean, why not life here?"

"I don't know why not," Hargraves shrugged. "For that matter, I don't know why, either." He looked closely at Ron Val. "You ape! I believe you're hoping we will find life here."

"Of course that's what I'm hoping," Ron Val answered quickly. "It would mean a lot to find people here. We could exchange experiences, learn a lot. I know it's probably too much to hope for." He broke off. "Jed, are we going to land here?"

"Certainly we're going to land here!" Jed Hargraves said emphatically. "Why in the hell do you think we've crossed thirty light years if we don't land on a world when we find one? This is an exploring expedition—"

Hargraves saw that he had no listener. Ron Val had listened only long enough to learn what he wanted to know, then had dived back to his beloved telescope to watch the world spiraling up through space toward them. That world meant a lot to Ron Val, the thrill of discovery, of exploring where a human foot had never trod in all the history of the universe.

New lands in the sky! The Third Interstellar Expedition—third because two others were winging out across space, one toward Sirius, the other toward Cygnus—was approaching land! The fact also meant something to Jed Hargraves, possibly a little less than it did to Ron Val because Hargraves had more responsibilities. He was captain of the ship, commander of the expedition. It was his duty to take the ship to Vega, and to bring it safely home.

Half of his task was done. Vega was bright in the sky ahead and the tough bubble of steel and quartz that was the ship was dropping down to rest on one of Vega's planets. Hargraves started to leave the nook that housed Ron Val and his telescope.

The ship's loudspeaker system shouted with sudden sound.

"Jed! Jed Hargraves! Come to the bridge at once."

That was Red Nielson's voice. He was speaking from the control room in the nose of the ship. Nielson sounded excited.

Hargraves pushed a button under the loudspeaker. The system was two-way, allowing for intercommunication.

"Hargraves speaking. What's wrong?"

"A ship is approaching. It is coming straight toward us."

"A ship! Are you out of your head? This is Vega."

"I don't give a damn if it's Brooklyn! I know a space ship when I see one. And this is one. Either get up here and take command or tell me what you want done."

Discipline among the personnel of this expedition was so nearly perfect there was no need for it. Consequently there was none. Before leaving earth, skilled mental analysts had aided in the selection of this crew, and had welded it together so artfully that it thought, acted, and functioned as a unit. Jed Hargraves was captain, but he had never heard the word spoken, and never wanted to hear it. No one had ever put "sir" after his name. Nor had anyone ever questioned an order, after it was given. Violent argument there might be, before an order was given, with Hargraves filtering the pros and cons through his rigidly logical mind, but the instant he reached a decision the argument stopped. He was one of the crew, and the crew knew it. The crew was one with him, and he knew it.

He might question Nielson's facts, once, in surprise. But not twice. If Nielson said a ship was approaching, a ship was approaching.

"I'm coming," Hargraves rapped into the mike. "Turn full power into the defense screen. Warn the engine room to be ready for an emergency. Sound the call to stations. And Red, hold us away from this planet."

Almost before he had finished speaking, a siren was wailing through the ship. Although he had used the microphone in the nook that housed the telescope, Ron Val had been so interested in the world they were approaching that he had not heard the captain's orders. He heard the siren.

"What is it, Jed?"

Hargraves didn't have time to explain. He was diving out the door and racing toward the bridge in the nose of the ship. "Come on," he flung back over his shoulder at Ron Val. "Your post is at the fore negatron."

Ron Val took one despairing glance at his telescope, then followed the commander.

As he ran toward the control room, Hargraves heard the ship begin to radiate a new tempo of sound. The siren was dying into silence, its warning task finished. Other sounds were taking its place. From the engine room in the stern was coming a spiteful hiss, like steam escaping under great pressure from a tiny vent valve. That was the twin atomics, loading up, building up the inconceivable pressures they would feed to the Kruchek drivers. A slight rumble went through the ship, a rumble seemingly radiated from every molecule, from every atom, in the vessel. It was radiated from every molecule! That rumble came from the Kruchek drivers warping the ship in response to the controls on the bridge. Bill Kruchek's going-faster-than-hell engines, engineers called them. A fellow by the name of Bill Kruchek had invented them. When Bill Krucheck's going-faster-than-hell drivers dug their toes into the lattice of space and put brawny shoulders behind every molecule within the field they generated, a ship within that field went faster than light. The Kruchek drivers, given the juice they needed in such tremendous quantities, took you from hell to yonder in a mighty hurry. They had been idling, drifting the ship slowly in toward the planet. Now, in response to an impulse from Nielson on the bridge, they grumbled, and hunching mighty shoulders for the load, prepared to hurl the ship away from the planet. Hargraves could feel the vessel surge in response to the speed. Then there was a distant thud, and he could feel the surge no longer. The anti-accelerators had been cut in, neutralizing the effect of inertia.

Shoving open a heavy door, Hargraves was in the control room. A glance showed him Nielson on the bridge. Leaning over, his fingers on the bank of buttons that controlled the ship, he was peering through the heavy quartzite observation port at something approaching from the right. Beside him, on his right, a man was standing ready at the radio panel. And to the left of the bridge two men had already jerked the covers from the negatron and were standing ready beside it.

Ron Val leaped past Hargraves, dived for a seat on the negatron. That was his post. He had been chosen for it because of his familiarity with optical instruments. Along the top of the negatron was a sighting telescope. Ron Val looked once to see where the man on the bridge was looking, then his fingers flew to the adjusting levers of the telescope. The negatron swung around to the right, centered on something there.

"Ready," Ron Val said, not taking his eyes from the 'scope.

"Hold your fire," Hargraves ordered.

He was on the bridge, standing beside Red Nielson. Off to the right he could see the enemy ship. Odd that he should think of it as an enemy. It wasn't. It was merely a strange ship. But there were relics in his mind, vague racial memories, of the days when stranger and enemy were synonymous. The times when this was true were gone forever, but the thoughts remained.

"Shall we run for it?" Nielson questioned, his hands on the controls that would turn full power into the drivers.

"No. If we run, they will think we have some reason for running. That might be all they would need to conclude we are up to no good. Is the defense screen on full power?"

"Yes." Nielson pushed the lever again to be sure. "I'm giving it all it will take."

Hargraves could barely see the screen out there a half mile from the ship. It was twinkling dimly as it swept up cosmic dust.[1]

The oncoming ship had been a dot in the sky. Now it was a round ball.

"Try them on the radio," Hargraves said. "They probably won't understand us but at least they will know we're trying to communicate with them."

There was a swirl of action at the radio panel.

"No answer," the radio operator said.

"Keep trying."

"Look!" Nielson shouted. "They've changed course. They're coming straight toward us."

The ball had bobbled in its smooth flight. As though caught in the attraction of a magnet it was coming straight toward them.

For an instant, Hargraves stared. Should he run or should he wait? He didn't want to run and he didn't want to fight. On the other hand, he did not want to take chances with the safety of the men under his command.

His mission was peaceful. Entirely so. But the ball was driving straight toward them. How big it was he could not estimate. It wasn't very big. Oddly, it presented a completely blank surface. No ports. And, so far as he could tell, there was no discharge from driving engines. The latter meant nothing. Their own ship showed no discharge from the Kruchek drivers. But no ports—

It came so fast he couldn't see it come. The flash of light! It came from the ball. For the fractional part of a second, the defense screen twinkled where the flash of light hit it. But—the defense screen was not designed to turn light or any other form of radiation. The light came through. It wasn't light. It carried a component of visible radiation but it wasn't light. The beam struck the earth ship.

Clang!

From the stern came a sudden scream of tortured metal. The ship rocked, careened, tried to spin on its axis. On the control panels, a dozen red lights flashed, winked off, winked on again. Heavy thuds echoed through the vessel. Emergency compartments closing.

Hargraves hesitated no longer.

"Full speed ahead!" he shouted at Red Nielson.

"Ron Val. Fire!"

This was an attack. This was a savage, vicious attack, delivered without warning, with no attempt to parley. The ship had been hit. How badly it had been damaged he did not know. But unless the damage was too heavy they could outrun this ball, flash away from it faster than light, disappear in the sky, vanish. The ship had legs to run. There was no limit to her speed. She could go fast, then she could go faster.

"Full speed—"

Nielson looked up from the bank of buttons. His face was ashen. "She doesn't respond, Jed. The drivers are off. The engine room is knocked out."

There was no rumble from Bill Kruchek's going-faster-than-hell engines. The hiss of the atomics was still faintly audible. Short of annihilation, nothing could knock them out. Energy was being generated but it wasn't getting to the drive. Leaping to the controls, Hargraves tried them himself.

They didn't respond.

"Engine room!" he shouted into the communication system.

There was no answer.

The ship began to yaw, to drop away toward the planet below them. The planet was far distant as yet, but the grasping fingers of its gravity were reaching toward the vessel, pulling it down.

Voices shouted within the ship.

"Jed!"

"What happened?"

"Jed, we're falling!"

"That ball, Jed—"

Voices calling to Jed Hargraves, asking him what to do. He couldn't answer. There was no answer. There was only—the ball! It was the answer.

Through the observation port, he could see the circular ship. It was getting ready to attack again. The sphere was moving leisurely toward its already crippled prey, getting ready to deliver the final stroke. It would answer all questions of this crew, answer them unmistakably. It leered at them.

Wham!

The ship vibrated to a sudden gust of sound. Something lashed out from the vessel. Hargraves did not see it go because it, too, went faster than the eye could follow. But he knew what it was. The sound told him. He saw the hole appear in the sphere. A round hole that opened inward. Dust puffed outward.

Wham, wham, wham!

The negatron! The blood brother of the defense screen, its energies concentrated into a pencil of radiation. Faster than anyone could see it happen, three more holes appeared in the sphere, driving through its outer shell, punching into the machinery at its heart.

The sphere shuddered under the impact. It turned. Light spewed out of it, beaming viciously into this alien sky without direction. Smoke boiled from the ball. Turning it seemed to roll along the sky. It looked like a huge burning snowball rolling down some vast hill.

Ron Val lifted a white face from the sighting 'scope of the negatron.

"Did—did I get him?"

"I'll say you did!" Hargraves heard somebody shout exultantly. He was surprised to discover his own voice was doing the shouting. The sphere was finished, done for. It was out of the fight, rolling down the vast hill of the sky, it would smash on the planet below.

They were following it.

There was still no answer from the engine room.

"Space suits!" Hargraves ordered. "Nielson, you stay here. Ron Val, you others, come with me."

The engine room was crammed to the roof with machinery. The bulked housings of the atomics, their heavy screens shutting off the deadly radiations generated in the heart of energy seething within the twin domes, were at the front. They looked like two blast furnaces that had somehow wandered into a space ship by mistake and hadn't been able to find their way out again. The fires of hell, hotter than any blast furnace had ever been, seethed within them.

Behind the atomics were the Kruchek drivers, twin brawny giants chained to the treadmill they pushed through the skies. Silent now. Not grumbling at their task. Loafing. Like lazy slaves conscious of their power, they worked only when the lash was on them.

Between the drivers was the control panel. Ninety-nine percent automatic, those controls. They needed little human attention, and got little. There were never more than three men on duty here. This engine room almost operated itself.

It had ceased to operate itself, Jed Hargraves saw, as he forced open the last stubborn air-tight door separating the engine room from the rest of the ship. Ceased because—Involuntarily he cried out.

He could see the sky.

A great V-shaped notch straddled the back of the ship. Something, striking high on the curve of the hull, had driven through inches of magna steel, biting a gigantic chunk out of the ship. The beam from the sphere! That flashing streak of light that had driven through the defense screen. It had struck here.

"Jed! They're dead!"

That was Ron Val's voice, choking over the radio. One of the men in this engine room had been Hal Sarkoff, a black-browed giant from somewhere in Montana. Engines had behaved for Sarkoff. Intuitively he had seemed to know mechanics.

He and Ron Val had been particular friends.

"The air went," Hargraves said. "When that hole was knocked in the hull, the air went. The automatic doors blocked off the rest of the ship. The poor devils—"

The air had gone and the cold had come. He could see Sarkoff's body lying beside one of the drivers. The two other men were across the room. A door to the stern compartment was there. They were crumpled against it.

Hargraves winced with pain. He should have ordered everyone into space suits. The instant Nielson reported the approach of the sphere, Hargraves should have shouted, "Space suits" into the mike. He hadn't.

The receiver in his space suit crisped with sound.

"Jed! Have you got into that engine room yet? For cripes sake, Jed, we're falling."

That was Nielson, on the bridge. He sounded frantic.

Sixteen feet the first second, then thirty-two, then sixty-four. They had miles to fall, but their rate of fall progressed geometrically. They had spent many minutes fighting their way through the air tight doors. One hundred and twenty-eight feet the fourth second. Jed's mind was racing.

No, by thunder, that was acceleration under an earth gravity. They didn't know the gravity here. It might be less.

It might be more.

Ron Val had run forward and was kneeling beside Sarkoff.

"Let them go," Hargraves said roughly. "Ron Val, you check the drivers. You—" Swiftly he assigned them tasks, reserving the control panel for himself.

They were specialists. Noble, the blond youth, frantically examining the atomics, was a bio-chemist. Ushur, the powerfully built man who had stood at Ron Val's right hand on the negatron, was an archeologist.

They were engineers now. They had to be.

"Nothing seems to be wrong here." That was Ron Val, from the drivers.

"The atomics are working." That was Noble reporting.

"Then what the hell is wrong?" At the control panel, Hargraves saw what was wrong. The damned controls were automatic, with temperature and air pressure cut-offs. When the air had gone from the engine room, that meant something was wrong. The controls had automatically cut off the drivers. The ship had stopped moving.

A manual control was provided. Hargraves shoved the switch home. An oil-immersed control thudded. The loafing giants grunted as the lash struck them, roared with pain as they got hastily to work on their treadmill.

The ship moved forward.

"We're moving!" That was Red Nielson shouting. The controls on the bridge were responding now. "I'm going to burn a hole in space getting us away from here."

"No!" said Hargraves.

"What?" There was incredulous doubt in Nielson's voice. "That damned sphere came from this planet."

"Can't help it. We've got to land."

"Land here, now!"

"There's a hole as big as the side of a house in the ship. No air in the engine room. Without air, we can't control the temperature. If we go into space, the engine room temperature will drop almost to absolute zero. These drivers are not designed to work in that temperature, and they won't work in it. We have to land and repair the ship before we dare go into space."

"But—"

"We land here!"

There was a split second of silence. "Okay, Jed," Nielson said. "But if we run into another of those spheres—"

"We'll know what to do about it. Ron Val. Ushur. Back to the bridge and man the negatron. If you see anything that even looks suspicious, beam it."

Ron Val and Usher dived through the door that led forward.

"Stern observation post. Are you alive back there?"

"We heard you, Jed. We're alive all right."

Back of the engine room, tucked away in the stern, was another negatron.

"Shoot on sight!" Hargraves said.

The Third Interstellar Expedition was coming in to land—with her fangs bared.

Jed Hargraves called a volunteer to hold the switch—it had to be held in by hand, otherwise it would automatically kick out again—and went forward to the bridge. Red Nielson gladly relinquished the controls to him.

"The sphere crashed over there," Nielson said, waving vaguely to the right.

Not until he stepped on the bridge did Jed Hargraves realize how close a call they had had. The fight had started well outside the upper limits of the atmosphere. They were well inside it now. Another few minutes and they would have screamed to a flaming crash here on this world and the Third Interstellar Expedition would have accomplished only half its mission, the least important half.

He shoved the nose of the ship down, the giants working eagerly at their treadmill now, as if they realized they had been caught loafing on the job and were trying to make amends. The planet swam up toward them. He barely heard the voice of Noble reporting a chemical test of the air that was now swirling around the ship. "—oxygen, so much; water vapor; nitrogen—" The air was breathable. They would not have to attempt repairs in space suits, then.

Abruptly, as they dropped lower, the contour of the planet seemed to change from the shape of a ball to the shape of a cup. The eyes did that. The eyes were tricky. But Jed knew his eyes were not tricking him when they brought him impressions of the surface below them.

A gently rolling world sweeping away into the distance, moving league after league into dim infinities, appeared before his eyes. No mountains, no hills, even. Gentle slopes rolling slowly downward into plains. No large rivers. Small streams winding among trees. Almost immediately below them was one of the lakes Ron Val had seen through his telescope. The lake was alive with blue light reflected from the—No, the light came from Vega, not Sol. They were light years away from the warming rays of the friendly sun.

Jed lowered the ship until she barely cleared the ground, sent her slowly forward seeking what he wanted. There was a grove of giant trees beside the lake. Overhead their foliage closed in an arch that would cut out the sight of the sky. This was what he wanted. He turned the ship around.

"Hey!" said Nielson.

"I'm going to back her out of sight among those trees," Hargraves answered. "I'm hunting a hole to hide in while we lie up and lick our wounds."

Overhead, boughs crashed as the ship slid out of sight. Gently he relaxed the controls, let her drop an inch at a time until she rested on the ground. Then he opened the switches, and grunting with relief, the giants laid themselves down on their treadmill and promptly went to sleep. For the first time in months the ship was silent.

"Negatron crews remain at your posts. I'm going to take a look."

The lock hissed as it opened before him. Hargraves, Nielson, Noble, stepped out, the captain going first. The ground was only a couple of feet away but he lowered himself to it with the precise caution that a twenty-foot jump would have necessitated. He was not unaware of the implications of this moment. His was the first human foot to tread the soil of a planet circling Vega. The great-grand-children of his great-grand-children would tell their sons about this.

The soil was springy under his feet, possessing an elasticity that he had not remembered as natural with turf. Opening his helmet, he sniffed the air. It was cool and alive with a heady fragrance that came from growing vegetation, a quality the ship's synthesizers, for all the ingenuity incorporated in them, could not duplicate. Tasting the air, the cells of his lungs eagerly shouted for more. He sucked it in, and the tensions that kept his body all steel springs and whipcord relaxed a little. A breeze stirred among the trees.

"Sweet Pete!" he gasped.

"That's what I was trying to tell you as we landed," Nielson said. "This is not a forest. This is a grove. These trees didn't just grow here in straight orderly lines. They were planted! We are hiding in what may be the equivalent of somebody's apple orchard."

The trees were giants. Twenty feet through at the butt, they rose a hundred feet into the air. Diminishing in the distance, they moved in regular rows down to the shore of the lake, forming a pleasant grove miles in extent. A reddish fruit, not unlike apples, grew on them.

If this was an orchard, where was the owner?

"Somebody coming!" the lookout called.

Jed Hargraves dropped the shovel. Behind him the hiss of an electric cutting torch and the whang of a heavy hammer went into sudden silence. Back there, a hundreds yards away, they had already begun work on the ship, attempting to repair the hole gouged in the stout magna steel of the hull. They had heard the call of the lookout and were dropping tools to pick up weapons. Jed's hand slid down to his belt to the compact vibration pistol holstered there. He pulled the gun, held it ready in his hand. Ron Val and Nielson did the same.

Vega, slanting downward, was near the western horizon. The grove was a mass of shadows. Through the shadows something was coming.

"They're human!" Ron Val gasped.

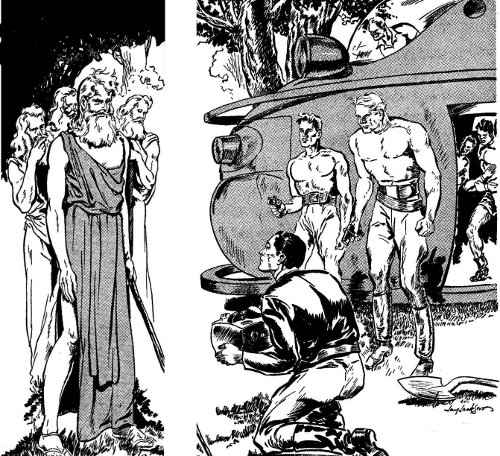

Hargraves said nothing. His fingers tightened around the butt of the pistol as he waited. He saw them clearly now. There were four of them. They looked like—old men. Four tribal gray-beards out for a stroll in the cool of the late afternoon. Each carried a staff. They were walking toward the ship. Then they saw the little group that stood apart and turned toward them.

"The teletron. Will you go get it, please, Ron Val?"

Nodding, the astro-navigator ran back to the ship. The teletron was a new gadget, invented just before the expedition left earth. Far from perfection as yet, it was intended to aid in establishing telepathic communication between persons who had no common language. Sometimes it worked, a little. More often it didn't. But it might be useful here. Ron Val was panting when he returned with it.

"Are you going to talk to them, Jed?"

"I'm going to try."

The four figures approached. Hargraves smiled. That was to show his good intentions. A smile ought to be common language everywhere.

The four strangers did not return his smile. They just stopped and looked at him with no trace of emotion on their faces.

They looked human. They weren't, of course. Parallel evolution accounted for the resemblance, like causes producing like results.

Nielson was watching them like a hawk. Without making an aggressive move, the way he held his gun showed he was ready to go into action at a moment's notice. Behind them, the ship was silent, its crew alert. Hargraves bent to manipulate the complicated tuning of the teletron.

"I am Thulon," a voice whispered in his brain. "No need for that."

Jed Hargraves' leaped to his feet. He caught startled glances from Ron Val and Nielson and knew they had heard and understood too. Understood, rather. There had been nothing for the ears to hear.

"Thulon! No need for—I understood you without—"

Thulon smiled. He was taller than the average human, and very slender. "We are natural telepaths. So there is no need to use your instrument."

"Uh? Natural telepaths! Well, I'm damned!"

"Damned? I cannot quite grasp the meaning of the word. Your mind is radiating on an emotional level. Do you wish to indicate surprise? I cannot grasp your thinking."

Hargraves choked, fought for control of his mind. For a minute it had run away with him. He brought it to heel.

"What are you doing here?" Thulon asked.

Hargraves blinked at the directness of the question. They certainly wasted no time getting down to business. "We—" He caught himself. No telling how much they could take directly from his mind!

"We came from—far away." He tried to force his thoughts into narrow channels. "We—"

"There is no need to be afraid." Thulon smiled gently. Or was there wiliness in that smile? Was this stranger attempting to lure him into a feeling of false security?

"I meant, what are you doing here?" Thulon continued. His eyes went down to the ground.

There was only one shovel on the ground. One shovel was all there had been in the ship. Thulon's glance went to it, went on.

There were three mounds. The soft mould had dug easily. It had all been patted back into place. On the middle mound Ron Val had finished placing a small cross that he had hastily improvised from the ship's stores. Scratched in the metal was a name: Hal Sarkoff.

"We had an outbreak of buboes," Hargraves said. "That's a disease. Three of our companions died and we landed here to bury them. We had just finished doing this when you arrived."

"Died! Three of you died? And you hid them under these mounds?"

"Yes. Of course. There was nothing else we could—"

"You are going to leave them here in the ground!"

"Certainly." Hargraves was wondering if this method of disposing of the dead violated some tribal taboo of this people. Different races disposed of their dead in different ways. He did not know the customs of the inhabitants of this world. "If we have offended against your customs, we are sorry."

"No. There was no offense." Thulon blanketed his thoughts. Hargraves could almost feel the blanket slip into place.

"You came in that ship?" Thulon pointed toward the vessel.

"Yes." It was impossible to conceal this fact.

"Ah." Thulon hesitated, seemed to grope through his mind for the exact shade of expression he wished to convey. Hargraves was aware that the stranger's eyes probed through him, measured him. "It would interest us to examine the vessel. Would you permit this?"

"Certainly." Hargraves knew that Red Nielson jerked startled eyes toward him.

"Jed!" Nielson spoke in protest.

"Shut up!" Hargraves snapped. His body and his mind was a mass of tightly wound springs but his face was calm and his voice was suave. He turned to Thulon. "I will be glad to take you through our ship. However, I do not recommend it."

"No?"

"It might be dangerous, for you and your companions. We have had three cases of buboes, resulting in three deaths. All of us have had shots of immunizing serum and we hope we will have no more cases. However, the germs are unquestionably present in the atmosphere of the ship. Since you probably have no immunity to the disease, to breathe the tainted air would almost certainly result in an attack. This disease is fatal in nine cases out of ten. I therefore suggest you do not enter the ship. In fact," Hargraves concluded, "I was about to say that it might not be wise for you and your companions even to come near us, because of the possibility that you might contract the disease."

Had he gotten the story over it? Was it convincing? Out of the corner of his eyes he saw Ron Val glance at him. When he had said their companions had died of buboes, Ron Val had looked as if he thought he was out of his mind. Now Ron Val understood. "Good going, Jed," his glance seemed to say.

"Hargraves—" This was Nielson speaking. His face was black.

"I suggest," said Jed casually, "that you let me handle this."

Nielson gulped. "Yes. Yes, sir," he said.

Thulon's companions had been paying attention to the conversation. But all the time they were stealing glances at the ship. With half their minds, they seemed to be listening to what was being said. But the other half of their minds was interested in that silent ship hidden under the trees. Were they merely curious, such as any savage might be? Or was this group making a reconnaissance? Hargraves did not know. It did not look like a reconnaissance in force.

"Do you really think we might contract this disease?" Thulon asked.

Hargraves shrugged. "I'm not certain. You might not. It would all depend on the way your bodies reacted to the organism causing the disease."

"Under such circumstances, you show little consideration for our welfare by bringing a plague ship to land here."

"We didn't know you existed. I assure you, however, that if you will remain away from the ship until we have an opportunity to disinfect it thoroughly, any danger to your people will be very slight. On the other hand, if you wish to look our vessel over, to assure yourselves that we are not a menace to you—which we are not—I shall be glad to take you through the ship."

Was he drawing it too fine? He spoke clearly and forcefully. The words, of course, would carry no meaning. But the thought that went along with them would convey what he wanted to say.

"Ah." The thought came from Thulon. "Perhaps—" Again the blanket came over his mind and Hargraves had the impression Thulon was conferring with his companions.

The silent conference ended.

"Perhaps," Thulon said. "It would be better if we returned to visit you tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow."

He bowed. Without another word he and his silent companions turned and began to walk slowly away. Not until he saw the little group slipping away into the dusk did Jed realize he had been holding his breath.

"Hargraves!" Nielson's voice was harsh. "Are you going to let them get away? You fool! That sphere came from this world. Have you forgotten?"

"I have forgotten nothing, I hope."

"But you offered to take them through the ship! They would have seen how badly damaged she is."

"Of course I offered to take them through the ship, then made it impossible for them to accept. We can't stick up 'No Trespassing' signs here. This is their world. We don't know a damned thing about it, or about them. We can't run and we don't want to fight, if we can help it. Furthermore, Nielson, I want you to learn to control your tongue. Remember that in the future, will you?"

For a second, Nielson glared at him. "Yes, sir."

"All right. Go on back to the ship."

Nielson went clumping back toward the vessel. Hargraves turned to Ron Val.

"What do you make of it?"

"I don't know, Jed. There is something about it that I don't like a little bit. They can read minds. Maybe that is what I don't like because I don't know how to react to it. Jed, it may be that we are in great danger here."

"There is little doubt about that," Hargraves answered. "Tonight we will stand watches. Tomorrow we will make a reconnaissance of our own."

Dusk came over the grove. Vega hesitated on the horizon as though trying to make up its mind, then abruptly took the plunge and dived from sight beyond the rim of the world. Night came abruptly, hiding the ship and its occupants. In the sky overhead, stars twinkled like the eyes of watchful wolves.

They blacked out the ship before they moved it, carefully covering each port with paper, then showing no lights. Hargraves handled the controls himself, slowly turning current into the drivers so their grunting would not reveal what was happening.

"Are we going to take her up high for tonight?" Ushur, the archeologist asked. "She will fly all right as long as we stay in the atmosphere. We would be safer up high, it seems to me."

"Safer from ground attack, yes," Hargraves said thoughtfully. "However, I'm afraid we would be more exposed to attack from a ship."

"Oh! That damned sphere. I had forgotten about it."

Hargraves moved the ship less than a mile, carefully hid her among the trees. Then he posted guards outside all the ports. He took the first watch himself, in the control room. Ron Val was waiting for him there. The astro-navigator's face was grave. "Jed," he said. "I've been talking to several of the fellows. They don't believe you are taking a sufficiently realistic view of our situation. They don't believe you are facing the facts."

"Um. What facts have I been evading?"

"You apparently don't realize that it will take months—if it can be done at all—to repair the damage to the ship."

Hargraves settled deep into his chair. He looked at the astro-navigator. Ron Val wasn't angry. Nor was he mutinous. He wasn't challenging authority. He was just scared.

"Ron," he said, "according to the agreement under which we sailed, any time the majority of the members of this expedition wants a new captain, they can have him."

"It isn't that."

"I know. You fellows are scared. Hells bells, man! What do you think I am?"

Ron Val's eyes popped open. "Jed! Are you? You don't show it. You don't seem even to appreciate the spot we're in."

Hargraves slowly lit a cigarette. The fingers holding the tiny lighter did not shake. "If I had been the type to show it, do you think I would have been selected to head this expedition?"

"No. But—"

"Because I haven't made an official announcement that we may not be able to repair the ship, you seem to think I don't realize the fact. I know how big a hole has been ripped in our hull. I know the ship is made of magna steel, the toughest, hardest, most beautiful metal yet invented. I know the odds are we can't repair the hole in the hull. We don't have the metal. We don't have the tools to work it. I know these things. When I didn't call it to your attention, I assumed it was equally obvious to everyone else that we may never leave this planet."

"Jed! Never leave this planet! Never—go home! That can't be right."

"See," said Hargraves. "When you get the truth flung in your face, even you crack wide open. Yes, it's the truth. The fact you fellows think I'm not facing—the one you don't dare face—is that we may be marooned here for the rest of our lives."

That was that. Ron Val went aft. Hargraves took up his vigil on the bridge. At midnight Ron Val came forward to relieve him.

"I told them what you said, Jed," the astro-navigator said. "We're back of you one hundred per cent."

Hargraves grinned a little. "Thanks," he said. "We were selected to work together as a unit. As long as we remain a unit, we will have a chance against any enemy."

Dog-tired, he went to his bunk and rolled in. It seemed to him he had barely closed his eyes before a hand grabbed him by the shoulder and a shaken voice shouted in his ear. "Jed! Wake up."

"Who is it? What's wrong?" The room was dark and he couldn't see who was shaking him.

"Ron Val." The astro-navigator's voice was hoarse with the maddest, wildest fright Hargraves had ever heard. "The—the damnedest thing has happened!"

"What?"

"Hal Sarkoff—" That was as far as Ron Val could get.

"What about him?"

"He's outside trying to get in!"

"Have you gone insane? Sarkoff is dead. You helped me bury him."

"I know it. Jed, he's outside. He wants in."

Hargraves had gone to bed without removing even his shoes. He ran forward to the control room, Ron Val pounding behind him. Lights had been turned on here, in defiance of orders. Someone had summoned the crew. They were all here, all eighteen who remained alive. The inner door of the lock was open. A dazed guard, who had been on watch outside the lock, was standing in the door. He had a pistol in his hand but he looked as if he didn't know what to do with it.

In the center of a group of men too frightened to move was a black-haired, rugged giant.

"Sarkoff!" Hargraves gasped.

The giant's head turned until his gaze was centered on the captain. "You moved the ship," he said accusingly. "I had the damnedest time finding it in the dark. What did you move the ship for, Jed?"

If some super-magician had cast a spell over the little group he could not have produced a more complete stasis. No one moved. No one seemed to breathe. All motion, all action, all thinking, had stopped.

Sarkoff's face went from face to face.

"What the heck is the matter with you guys?" he demanded. "Am I poison, or something?"

He seemed bewildered.

"Where—where are the others?" Ron Val stammered.

"What others? What the heck are you talking about, Ron?"

"Nevins and Reese. We—we buried them with you. Where are they?"

"How the hell do I kn——You buried them with me?" Sarkoff's face went from bewilderment to inexplicable good nature. "Trying to pull my leg, huh? Okay. I can go along with a gag." He looked again at Hargraves. "But I can't go along with that gag of moving the ship after you sent me out scouting. Why didn't you wait for me? Wandering around among all these trees, I might have got lost and got myself killed. Why did you do that, Jed?" he finished angrily.

"We were—ah—afraid of an attack," Hargraves choked out. "Sorry, Hal, but we—we had to move the ship. We would have—hunted you up, tomorrow."

Sarkoff was not a man who was ever long angry about anything. The apology satisfied him. He grinned. "Okay, Jed. Forget it. Jeepers! I'm so hungry I could eat a cow. How about a couple of those synthetic steaks we got in the ice-box?" His eyes went around the group, came to rest on the astro-navigator. "How about it, Ron? How about me and you fixing us up some chow?"

"Sure," said Hargraves. "Go on back to the galley and start fixing yourself whatever you want. You go with him, Ron. I'll handle your job up here while you're gone."

Nodding dumbly, Ron Val started to follow Sarkoff toward the galley. "One minute," Hargraves called after him. "I want to check something with you before you go!"

Sarkoff kept going. Ron Val returned. "Take your cues from him," Hargraves said. "You know him better than anyone else. Whatever he says, you agree. Casually bring up past events and watch his reaction. Your job is to find out if that is really Hal Sarkoff!"

The astro-navigator, his face white, clumped toward the galley.

Hargraves faced a torrent of questions.

"Jed! We buried him."

"Jed. He had been in that engine room without air for at least ten minutes before we got there. He can't be alive."

"No air. Temperature diving toward absolute zero. He was frozen stiff, Jed, before we moved him. We left him where he was until long after we landed."

"I know," Hargraves said. "There is no doubt about it. I used a stethoscope on him as soon as I could get to it after we landed. He was dead. There wasn't a sign of life."

Frightened faces looked at him. Awed faces. Bewildered faces.

"What did you mean when you told Ron Val to find out if that is really Sarkoff?"

"Just what I said. That may be Sarkoff. It may be something that looks like Sarkoff, acts like him, talks like him—but isn't he!"

"That—that's impossible."

"How do we know what is possible here and what isn't?"

"What are we going to do?"

"We're going to act just as we would if that were Sarkoff. We're going to pick up our cues from him? You remember he said he was out scouting. That is his story. We will not question it. We will act as though it were true, until we know what is happening. Now everybody back to his post. Act as if nothing had happened. And for the love of Pete, don't ask me what is going on. I don't know any more than you do."

They didn't want to obey that order. They had just seen a dead man walking, had heard him talking, had spoken to him. There was comfort in just being with each other. Hargraves walked to the bridge, waited. Eventually, discipline sent them back to their posts. He kept on waiting. Ron Val returned.

"I don't know, Jed. I just don't know. We were in school together. I brought up incidents that happened in school, things that only Hal and I knew. Jed, he knew them."

With the exception of a hooded blue lamp on the bridge, all lights had been turned off again. The control room was in darkness. Ron Val was an uneasy shadow talking from dim blackness.

"Then you think that it is really Sarkoff?"

"I don't know."

"But if he remembers things that only Hal could know—"

"He remembers things that he can't know."

"Um. What things?"

"He asked me how much progress had been made in repairing the ship. Jed, he must have died before he knew the ship had been damaged."

"Not necessarily," said Hargraves thoughtfully. "He might have been conscious for one or two minutes after the beam struck us. He would know that the ship had been damaged. What did you tell him?"

"I changed the subject."

"Good for you. If he isn't Sarkoff, the one thing he might want to know is whether the ship has been repaired. What else?"

"Jed, he remembers everything that happened after the ship was attacked. We almost crashed before we got the engines started. He remembers that. He remembers hiding the ship among the trees."

Hargraves stirred. The keen logic of his mind was being blunted by facts that would not fit into any logical pattern. He tried to think. His mind refused the effort. Dead men ought not to remember things that happened after they died. But a dead man had remembered!

For an instant panic walked through the captain's mind. Then he got it under control. There was always an answer to every question, a solution to every problem. Or was there? He went hunting facts.

"Does he remember being buried?"

Even in the darkness he could feel Ron Val shiver. "No," Ron Val said. "He doesn't remember. Just as soon as we landed, he thinks you sent him out, to scout the surrounding territory for possible enemies."

"Does he know that we had visitors in his absence?"

"No. Or if he does, he didn't mention it, and I didn't ask. He says he was returning when he saw the ship being moved. He says he tried to follow, but lost it in the darkness. He says he had the devil's own time finding it again, and he's still hot about being left behind."

Again Hargraves had to fight the panic in his mind. This much seemed obvious. Sarkoff's memory was accurate—until the ship landed. Then it went into fantasy, into error. If one thing was certain, he had not been sent out to scout for enemies. If there was another fact that was immutable, he had been buried.

"Where is he now?" Hargraves asked abruptly.

"In his bunk, snoring. He ate enough for two men, yawned, said he was sleepy. He was sound asleep almost as soon as he touched the blankets."

Ron Val's voice relapsed into silence. The whole ship was silent.

"Jed, what are we going to do?"

"You bunk with him, don't you?"

"Yes. Jed! You don't mean—"

Hargraves cleared his throat. "This is not an order. You don't have to do it if you don't want to. But Sarkoff must be watched. Are you willing to go back to the room you two shared together and get into the upper deck of your bunk just as if nothing has happened?"

"Yes," said Ron Val.

"Somebody must be with him—all the time. You stay awake. When he gets up, you get up. Whatever he does, you stay with him. I'll have you relieved as soon as possible. And, Ron—"

"Yes."

"You have something a man could use for courage."

Silently, Ron Val walked out of the control room. He fumbled his way through the door and his steps echoed down the corridor that led to the sleeping quarters.

Hargraves sat in thought. Then he, too, left the control room.

"Noble, you're a bio-chemist. You come with me. Nielson, you take over here in the control room. In my absence you are in command."

"Yes sir," Nielson said. "But what are you going to do?"

"See what is in a grave we dug yesterday," Hargraves answered.

Hargraves carried the shovel. He and Noble were armed, and very much alert.

"When you ask me if it is chemically possible for a man—or an animal—to freeze, die, be buried, then rise again and live, I cannot answer," Noble said. "So far as I know, it is not possible. The physical act of freezing will involve tremendous and seemingly irreversible changes in the body cells. Thawing will produce almost immediate bacterial action, which also seems irreversible. All I can say is, if Hal Sarkoff is alive, we have seen a miracle that contradicts chemical laws as we know them."

"And if he is not alive, we face a miracle of duplication. Whatever it is that is sleeping back in the ship, it looks, talks, acts, like Hal Sarkoff, even to memory. Can you suggest any method by which flesh and bone could be so speedily moulded into a living image of a man whom we know died?"

"No," said Noble bluntly. "Jed, do you realize all the possible implications of this situation?"

"Probably not," Hargraves answered. "Some that I do recognize, I exclude from my thoughts."

His tone was so harsh that Noble said nothing more.

Dawn was already breaking over this Vegan world. The sky in the east was the color of pearl. In the trees over them, creatures that sounded like birds were beginning to chirp.

They reached the place where they had buried Hal Sarkoff and his two companions.

The graves were empty.

No effort had been made to conceal the fact that the graves had been opened. The dirt had been shoveled out again and had not been shoveled back.

There were marks in the dirt, the tracks of sandaled feet. "Thulon, the three who were with him, wore sandals!" Hargraves rasped. "They came back here. They opened these graves."

"But what happened after that? Are you suggesting those primitive gray-beards resurrected Hal Sarkoff?"

"I'm not suggesting anything because I don't know anything," Hargraves answered. "I am just remembering that Thulon and the three who were with him looked human too! I am also remembering that the sphere which attacked us seemingly was without a crew. Our beams blasted it wide open. It was seemingly filled with machinery. Nothing else. If there were any intelligent creatures in it, they were in no form that we recognize. Come on!" Hargraves started running toward the ship.

The ship, badly damaged as it was, represented their sole hope of survival. Without it, they would be helpless.

Hal Sarkoff was with the ship. Or the thing that was masquerading as Sarkoff. Thulon had looked human too. Possibly Sarkoff and his two dead comrades had been removed from their graves in order to make possible a perfect duplication of their bodies, the probing of cell structure, both body and brain. Perhaps the things that lurked here on this world could read memories from dead minds. That might be the explanation of Sarkoff's memory.

The important fact was that Sarkoff's body was not in its grave. Where so much was unknown, this was one indisputable fact. The thing that was on the ship must be placed not only under heavy guard but in a cage from which escape was impossible. Then an examination could begin.

There was evil on this world. The trees, the vegetation, the ground under his racing feet, was evil. In his calmer moments Jed Hargraves would have said that evil was another word for danger. He wasn't calm now. The panic he had been rigidly excluding from his mind had burst the dam he had built before it. He could feel danger in the air. It was in the dawn, in the light of the sky. It was everywhere. He and his companions were aliens on this world, and the planet was striking at them, striving to eliminate them, contriving to destroy them.

He heard it before he saw it.

Something was grunting in the air. Above the tops of the trees something was grunting. He needed seconds to recognize the sound. Then he recognized it. And jerked himself to a halt, his eyes wildly probing upward.

He saw it.

The ship. The grunting roar had come from the Kruchek drivers fighting the gravity of the planet.

The ship had taken off without them.

Had Nielson gone mad? Had he seen danger approaching and jumped the ship into the sky to escape it?

"Wait! Nielson! Pick us up!"

The ship flew on. Gaining speed, it passed over their heads. They caught another glimpse of it as it passed over an opening in the branches of the trees. Then it was gone, the throb of the drivers dying quickly away.

"Nielson will come back for us." Noble's voice, usually poised and assured, was garbled. "He'll return and pick us up. He won't leave us here."

"He had some reason for taking off," Hargraves heard himself saying. "He'll come back. He has to." Subconsciously he knew that this, at the very best, was wishful thinking.

The ship had no more than vanished until another sound came to their ears, that of men shouting. A group came into sight among the trees, following along the ground the course the ship had taken through the air.

"They're our fellows!" Hargraves heard Noble gasp.

"What happened?" the captain demanded, as the group approached.

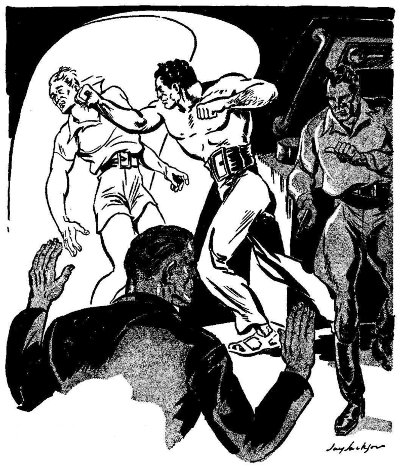

Nielson was in the lead. There was a bruise on his cheek and his right eye was already beginning to turn black. "I'll tell you what happened!" he said savagely. "Sarkoff and Ron Val took over the ship, that's what happened!"

"Ron Val!"

"That's what I said. Ron Val was helping him. They pulled guns. Before we knew what was happening, they had herded us together and were shoving us outside. I tried to stop it and Sarkoff took a poke at me."

"It wasn't really Sarkoff, then?" Noble whispered.

"Any damned fool would have known that!" Nielson answered. He spoke to the bio-chemist but his eyes were on Hargraves. "I'm going to repeat that, so there won't be any misunderstanding of my meaning. Any damned fool would have known that a dead man doesn't get up out of his grave and come to life again. Except you, Hargraves. You always were a sucker for fairy stories."

Jed Hargraves winced with every word that was spoken. They kept on coming.

"You ought to have known that thing wasn't Hal Sarkoff. Any man in his right senses would have known it instantly. Any man fit to command would have taken measures to meet the situation, either by destroying that thing, or locking it up. But you were running things, Hargraves. You were in charge. And you had to sit back and think before you would act. You had to make sure you were right, before you went ahead. Your negligence, Hargraves, cost us our only chance of ever returning home."

Nielson's voice was harsh with anger. And—Hargraves recognized the bitter truth—every word Nielson uttered was correct. Whatever the thing was that had come to the ship, he should have recognized it as a source of danger. He had so recognized it. But he had not acted.

"I—"

"Shut up!" Nielson snapped. "According to our agreement, any time you are shown to be unfit to command, you may be removed by a vote of the majority. There is no question but that you have shown yourself unfit to be in charge of this expedition."

No time was wasted in reaching a decision. To Nielson's question as to whether Hargraves should be removed from command, there was a chorus of "Ayes."

"No," said one voice. It was Usher, the archeologist.

"State your objection," Nielson rasped.

"The old one about changing horses in mid-stream," the archeologist answered. "Also the old one about not jumping to conclusions before all the evidence is in."

"What evidence isn't in?"

"We don't know why Ron Val joined Sarkoff," the archeologist answered.

"What difference does that make? We don't even know that Ron Val was still himself. The thing that looked like Ron Val might have been another monstrosity like Sarkoff."

"So it might," the archeologist shrugged. "Anyhow my vote is not important. I'm just putting it in for the sake of the record, if there ever is a record. I would also like to mention that if ever we needed discipline and unity, now is the time."

"We will have discipline, I promise you," Nielson said. "Hargraves, you are removed from command, understand?"

"Yes," said Hargraves steadily.

Only one ballot was needed to put Nielson in charge.

"All right," said Ushur to the new captain. "You're the boss now. We're all behind you. What are you going to do?"

"Do? I—" Nielson looked startled. He glanced at Hargraves.

The former captain sighed. It was easy enough to elect a new leader. Vehemently he wished that all problems could be solved so easily.

"I suggest," he said, "—and this is only a suggestion—that we attempt to find the ship, and if possible, to regain possession of her. She is the only tool we have to work with."

"That is exactly what I was going to say," Nielson said emphatically. "Find the ship."

To give him credit, he set about the job in a workmanlike manner, sending two scouts ahead of the main group, throwing out a scout on each flank. The only way they could hope to find the ship was by following the course it had taken through the air. Since Sarkoff, in taking over the vessel, had not disarmed them, each possessed a vibration pistol. In a fight against ordinary enemies they would be able to give a good account of themselves. But would any enemy they met likely be ordinary?

Hargraves drew Usher aside. "I would like to talk to you," he said. "What actually happened when the ship was taken?"

"I don't know, Jed," the archeologist ruefully answered. "I was in my cabin. The first thing I knew I heard a hell of a hullabaloo going on up in the control room. I dashed up there to see what was going on."

"What was happening?"

"Nielson, Rodney, Turner, and a couple of others were there. So were—well, they looked like Sarkoff and Ron Val. Nielson was getting up off the floor. Sarkoff and Ron Val had both drawn their guns and were covering the group. When I came charging in, Sarkoff covered me. Before I could recover from my surprise, he and Ron Val had kicked every one of us out of the ship. Then they took off." The archeologist shook his shaggy head.

"Ron Val was helping?"

"No question about it. Which means, of course, that he was either under some subtle form of hypnosis, or it wasn't Ron Val. I would bet my life on his loyalty."

"So would I," said Hargraves. And the memory came back of how thrilled Ron Val had been at the prospect of landing on this, world. "It would mean a lot to find people here. We could exchange experiences, learn a lot," Ron Val had said, his face glowing at the thought. All the others had felt the same way. The Third Interstellar Expedition had no military ambitions. It was not bent on conquest. The solar system had outgrown military expeditions, war, and the thought of war, and cruisers went out from it not to fight but to learn. Knowledge was the thing they sought, all knowledge, so the human race could determine its place in the cosmos, could know the history of all things past, could possibly forecast the shape of things to come.

The landing of the Third Interstellar Expedition on this Vegan world had been a part of a vast evolution, a march that, starting on earth so long ago that all history of it was forever lost, was now reaching out across the cosmos. A new evolution! Ron Val had always been talking about this new evolution. It was one of his favorite subjects.

"What do you make of this world?" Hargraves asked abruptly. "The only sign of civilization we have seen is this vast grove. No cities, no industrial plants, no evidence of progress. Yet the spherical ship that attacked us certainly indicates a highly mechanical civilization. Of course there may be cities here that we haven't seen, but as we landed we saw a large land area. No roads were visible, no canals, not even any cultivated fields. What does all this mean to you, as an archeologist?"

"Nothing," Usher answered promptly. "I would say this country is a wilderness. But the trees planted in regular rows disprove this. On earth, at least, centuries would be required for trees as large as these to grow. Forestry, planned centuries in advance, can only come from a high and stable culture. However, as you say, all other signs of this high culture are absent, no cities, no transportation facilities, apparently damned few inhabitants—we have seen only four. All civilizations with which we are familiar move through recognized stages, first the nomadic stage, which involves tending flocks and herds. Then comes the tilling of the soil, in which farming is the principal occupation of most of the people. After that, with industrialization, we have cities developing. If there is another stage we have not reached it on earth."

"Do you think they might have reached the final stage here?" Hargraves questioned.

"I don't know what the final stage may be," the archeologist answered. "Also, and this is more important, I can't begin to guess at the real nature of the inhabitants of this world. Until I do know their real nature, what they look like, what they eat, where they sleep, what they think, I can't even guess intelligently about them. However," Usher broke off with a wry grin, "all these philosophical observations are of no importance while our own necks are threatened with the ax."

Vega was straight overhead when they found the ship. One of the advance scouts came hurrying back with the information.

"She is lying in a little meadow beside the lake," the scout reported. "They're doing something to her. I can't tell what. But the trees extend to within fifty yards of her. We can approach that near without being seen."

Nielson made his dispositions with care. The ship lay in a little meadow where the trees bent inward from the blue water of the lake to form a cove. Her nose was pointed toward the water and her tail was almost in the trees. Nielson sent three men on a wide circuit. They were to attack from the farther side. It was to be a feint. While the three men drew attention to them, the main body was to charge.

"We have every chance of succeeding," Nielson said. "And if we do gain the ship again, this time we won't stay here. Vega has at least two planets. The ship will fly to the other one without repairs. You should have thought of that, Hargraves."

"There are a lot of things I should have thought of and didn't," Hargraves answered. There was no animosity in his tone. "What I would like to know is what they are doing there beside the ship?"

Thulon and his three companions were visible beside the vessel. They were busily engaged in setting up a device of some kind. Others of their species had joined them until there were possibly thirty or forty present. Through the the gaping hole in the hull, still others could be seen peering out. What they were doing Hargraves could not discern.

"Odd," said Usher beside him.

"What is?"

"It's odd that they should still seem to be human in form," the archeologist answered. "Ah. Perhaps there is the reason."

Both locks were open. The thing that looked like Hal Sarkoff had just emerged from the nearest one. He went directly to the main group. They were erecting something that looked like a tripod. Several were carrying pieces of metal from the ship which they were fastening together to form the legs of the tripod. At the apex of the tripod something that looked like a box was coming into existence.

"They are completely unarmed," Hargraves heard Nielson say. "There isn't a weapon in the whole damned bunch. We'll blast them senseless before they even know they're being attacked."

"If they don't succeed in manning the negatron," Usher pointed out.

"They don't know how to operate the negatron."

"Don't they? I might mention that they seem to know everything that Sarkoff knew. And Hal certainly knew how that negatron operated. He could take it apart and put it back together blind-folded."

"That's so," Nielson admitted. For a second unease showed on his lean face. "Well, that only means we will have to lick them before they can get that negatron into operation. One thing is certain—we have to have the ship."

"You're right on that score," Usher grimly said.

Seconds ticked away into minutes. The group busy about the ship had no intimation they were about to be attacked. They were careless to the point of foolhardiness. No sentries had been posted, no effort had been made to hide the vessel.

"What are they, really?" Hargraves thought. He wondered if they were some strange form of water-dwelling life that lived in the lakes of this planet. Perhaps that was what they were! Perhaps the transition from the fish to the mammal had never been made on this planet, the fish-form developing keen intelligence. Certainly there was intelligence on this world. But it seemed to be an intelligence humans could not comprehend.

The signal for the attack sounded. Fierce shouts came from the other side of the ship. The shouters were hidden, but there was no mistaking the sounds. They came from human throats.

"Give 'em hell, boys!"

"Tear 'em to pieces!"

The harsh throbbing of vibration pistols split the quiet air.

"Steady!" Nielson said. "Wait until they go to see what's happening."

The group busy around the ship raised startled faces from their task. They seemed to listen. Then they turned and ran around the bow of the vessel.

"Come on!" cried Nielson, leaping from concealment.

There wasn't a person left in sight to oppose them. Fifty yards to cross. Fifty yards to the ship! Fifty yards to a fighting chance for life!

Under their racing feet the soft turf was soundless.

Twenty-five yards to go now. Ten yards. Ten feet to the open lock.

Thulon appeared in the lock. He looked in surprise at the charging men.

Except for the rough staff that he carried he was weaponless.

Nielson didn't give the command to fire, didn't need to give it. Every vibration pistol had been drawn long before the men leaped from cover. Every pistol came up at the same instant, every index finger squeezed a trigger.

Only Thulon stood between them and a fighting chance for life. They came of warrior races, these men. No bugles urged them on. They needed no bugles.

A howling vortex of radiation smashed at the figure in the lock.

One vibration pistol would destroy a man, smash him to bloody bits. More than a dozen pistols were centered on the figure standing before them.

Thulon stood unharmed.

Staff in front of him he stood facing the fingers of hell reaching for him. The flaming fingers grasped, and did not touch him.

The shooting stopped as abruptly as it began. The charge stopped. Hargraves saw Nielson staring dazedly from the figure in the lock to the pistol in his hand as if the two were irreconcilable. The pistol ought to have destroyed Thulon. It hadn't destroyed him. For a mad moment, Hargraves felt sorry for the new captain. He, too, had run headlong into a logical impossibility.

All sounds were suddenly stilled, all shouting stopped, all noises died away.

Around the bow of the ship Hal Sarkoff came running. He saw the group and looked bewildered. "Hey! How did you guys get here?"

"Blast him!" Nielson said, centering his pistol on this new target.

From the staff in Thulon's hand came a soft tinkle, a bell-like sound. Nothing seemed to happen but Nielson staggered as if he had been hit a sharp blow. The pistol flew out of his hand and landed twenty feet away.

"Listen, you apes," Sarkoff shouted at the top of his voice. "I'm Hal Sarkoff. I've always been Hal Sarkoff. I'll never be anybody else but Hal Sarkoff. Do you get it?"

They didn't get it.

"If you—" Nielson whispered. "If you are really Sarkoff, then who—what—is he?" He pointed toward Thulon still standing in the lock.

"Him?" The grin on the craggy face belonged to Hal Sarkoff and to no one else. "Meet a god," he said.

"A god?" That was Usher speaking now, his voice a tense whisper.

Sarkoff continued grinning. "Well, he resurrected me when I was deader than hell. I guess that makes him a god."

"You—you know you were dead?"

"Yep. At least I guess I know it. The last thing I remember is trying to get back to the control panel when we got that hole knocked in the ship, so I could cut the drivers back in. After that everything gets kind of hazy. The next thing I remember is my pal here," he gestured toward Thulon, "and a lot of his buddies chirping like sparrows while they worked over me. And believe me, they were working me over plenty. I felt like I had been turned inside out, wrung out, hung out to dry, then stuffed all over again."

"But when you came back to the ship," Hargraves spoke, "you said you remembered everything that had happened, the crash of the ship, our hiding her. If you were dead, how did you learn these things?"

"He told me," Sarkoff answered, nodding toward Thulon. "He filled out my memory for me with dope he had taken from your mind while you were talking. Reading minds is one of that old boy's minor accomplishments."

"Then why didn't you tell us the truth?" Hargraves exploded. "You said you had been sent out scouting. Why didn't you tell us what had really happened?" Mentally he added, "If it happened!"

"Because you apes wouldn't have believed me!" Sarkoff answered. "To your knowledge—mine, too, until it happened—dead men don't get up out of their graves and walk. If I had told you the truth, you wouldn't have believed a word of it. If I told you something you knew wasn't true, that you had sent me out on a scouting trip, you would know I was lying, you would figure it was a trick of some kind, and you would wait around and try to discover the trick. While you were waiting around trying to catch me, I could get in some missionary work on Ron Val. I knew I could convert him, if I had a chance to talk to him. With him on my side, we could convince the rest of you. It would have worked too. All it needed was a little time for you boys to get used to the idea of a dead man coming back to life." He looked at Nielson. "Remind me to black that other eye of yours one of these days."

"What?" said Hargraves. "What's this?"

"Our pal Nielson," Sarkoff said. "If you think before you act, he acts before he thinks. You had no sooner gone chasing off to see if I was really where you had buried me, which was what I thought you would do, until Nielson comes poking into where Ron Val and I were holding a conference. Nielson had a gun. He had it out ready to use. He figured the only safe thing to do was to shoot me. So," Sarkoff shrugged, "I had to smack him. He had forced my hand."

There was a slight stir among the group. This was news to all of them.

"Is this true?" Hargraves said.

"Yes," said Nielson defiantly. "And I was right. I should have killed him. He isn't Hal Sarkoff. He isn't telling the truth about coming back to life. Sarkoff is dead."

Sarkoff glanced up at Thulon who was still standing in the lock looking down at the men before him. There was a ghost of a smile on his face.

"See!" said Sarkoff, addressing Thulon. "I told you we couldn't tell these boys anything. They have to see, they have to feel, they have to be shown."

"Well," the thought came from Thulon to everyone. "Why don't you show them?"

"Okay," Sarkoff answered. "Nevins!" he shouted. "Reese! Come out of that ship."

Nevins and Reese were the two engineers who had died with Sarkoff.

Thulon moved a little to one side. Nevins and Reese came out of the ship. They were grinning.

"Feel us!" Sarkoff shouted. "Pinch us. Cut off a slice of skin and examine it under a microscope. Make blood tests. Use X-rays. Do whatever you damned please." He shoved a brawny arm under Nielson's nose. "Here. Pinch this and see if you think it's real."

Nielson shrank away.

Nevins and Reese passed among the men, offering themselves in evidence. Startled voices called softly in answer to other startled voices. "They're real."

"This is no lie. This is the truth."

"I've known this man for years. This is Eddie Nevins."

"And this is Sam Reese."

Hargraves heard the voices, saw the conclusion they were reaching.

"One moment," he said.

The voices went into silence. Eyes turned questioningly to him.

"Even if these men are really Hal Sarkoff and Eddie Nevins and Sam Reese, if they are the companions we knew as dead who have miraculously been returned to us, there are still facts that do not fit into a logical pattern. Even here on this world the laws of logic must hold true."

Silence fell. Men looked at him and at each other. Where there had been wonder on their faces, new doubts were appearing.

"What facts, Jed?" Sarkoff questioned.

"The sphere that attacked us, that attempted to destroy us, without warning. This is a fact that does not fit."

"The sphere?" Uncertainty showed on Sarkoff's face. Then he grinned again and turned to Thulon. "You tell him about that sphere."

"Gladly," Thulon's thoughts came. "As you know, Vega has two planets. Long ago we were at war with the inhabitants of this other planet. Part of our defenses around our own planet were floating fortresses. The war is done but we have left guards in the sky to protect us if we are attacked. The sphere that attacked you was one of our automatic forts which we had left in the sky."

"Ah!" said Hargraves. The cold logic of his mind sought a pattern that would include fortresses in the sky. Presuming war between two planets, such fortresses were logical. But—

"The construction of such a sphere indicates vast technical knowledge, tremendous workshops. I have seen no laboratories and no industrial centers that could produce such a fortress. I have, moreover, seen no civilization that will serve as a background for such construction."

He waited for an answer. Usher, the archeologist, looked suddenly at him, then looked at Thulon.

"The fortresses were built long ago," Thulon said. "In those past milleniums we had industrial centers. We no longer need them and we no longer have them."

"Then there is another stage!" the archeologist gasped. "You are past the city stage in your evolutionary process. You are beyond the metal age. What—" Usher eagerly asked. "What comes after that?"

"We are beyond the age of cities," Thulon answered. "The next but possibly not final stage is a return to nature. We live in the groves and the fields, beside the lakes, under the trees. We need no protection from the elements because we are in unison with them. There are no enemies on this world, no dangers, almost no death. In your thinking you can only describe us as gods. Our activities are almost entirely mental. Our only concession of materialism is this." He lifted the staff. "When you fired at me, this staff canceled your beams. It would have canceled them if they had been a thousand times stronger. When one of you attempted to destroy Sarkoff, force went out from this staff, knocking the weapon from his hand. There are certain powers leashed within this staff, certain arrangements of crystals that are very nearly ultimate matter. Through this staff my will is worked. Some day," he smiled, "we will even be able to discard the staff. That is the goal of our evolution."

The thoughts went into soft silence and Thulon looked down at them. "Does that satisfy you?" His eyes went among the group, came to rest on Hargraves. "No, I see it does not. There is still one fact that you cannot fit into your pattern."

"Yes," said Hargraves. "If all that you have told us is true, why was the ship stolen?"

"Everything has to fit for you?" Sarkoff answered. "Well, that's why you are our leader. I can answer this question. I took the ship so I could have it repaired. Then, when I brought it back to you, fit to fly again, all of us would have evidence that we could not deny. You might doubt my identity, you might doubt me, but you would not doubt a ship that had been repaired. Thulon," Sarkoff ended, "will you do your stuff?"

Standing a little apart from the rest Hargraves watched. Thulon and his comrades brought metal from the vessel. How they used the tripod he could not see but in some way they seemed to use it to melt the metal. This was magna steel. They worked it as if it were pure tin. It didn't seem to be hot but they spread sheets of it over the gaping hole in the hull. They closed the hole. He knew the ship had been repaired but still he did not move. On the ground before him was something that looked like an ant hill. He watched this, his mind reaching out and grasping a bigger problem. The ants, he could see, were swarming.

Nielson detached himself from the group at the ship and came to him.

"Jed," he said hesitatingly.

"What?"

"Jed, what Hal said about me attacking him was right. I thought—I thought he wasn't Sarkoff. I thought I was doing what was right."

"I don't doubt you," Hargraves answered. His mind was not on what Nielson was saying.

"Jed."

"Uh?"

"Jed. I—"

"What is it?"