The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 8, Slice 5, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 8, Slice 5

"Dinard" to "Dodsworth"

Author: Various

Release Date: June 4, 2010 [EBook #32689]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOL 8 SL 5 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

Transcriber's note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version.

Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will

be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online.

|

THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME VIII SLICE V

Dinard to Dodsworth

Articles in This Slice

| DINARD | DISSECTION |

| DINDIGUL | DISSENTER |

| KARL WILHELM DINDORF | DISSOCIATION |

| D’INDY, PAUL-MARIE-THÉODORE-VINCENT | DISSOLUTION |

| DINEIR | DISTAFF |

| DINGELSTEDT, FRANZ VON | DISTILLATION |

| DINGHY | DISTRACTION |

| DINGLE | DISTRESS |

| DINGO | DISTRIBUTION |

| DINGWALL | DISTRICT |

| DINKA | DISTYLE |

| DINKELSBÜHL | DITHMARSCHEN |

| DINNER | DITHYRAMBIC POETRY |

| DINOCRATES | DITTERSBACH |

| DINOFLAGELLATA | DITTERSDORF, KARL DITTERS VON |

| DINOTHERIUM | DITTO |

| DINWIDDIE, ROBERT | DITTON, HUMPHRY |

| DIO CASSIUS | DIU |

| DIOCESE | DIURETICS |

| DIO CHRYSOSTOM | DIURNAL MOTION |

| DIOCLETIAN | DIVAN |

| DIOCLETIAN, EDICT OF | DIVER |

| DIODATI, GIOVANNI | DIVERS and DIVING APPARATUS |

| DIODORUS CRONUS | DIVES-SUR-MER |

| DIODORUS SICULUS | DIVIDE |

| DIODOTUS | DIVIDEND |

| DIOGENES | DIVIDIVI |

| DIOGENES APOLLONIATES | DIVINATION |

| DIOGENES LAËRTIUS | DIVINING-ROD |

| DIOGENIANUS | DIVISION |

| DIOGNETUS, EPISTLE TO | DIVORCE |

| DIOMEDES (Greek legend) | DIWANIEH |

| DIOMEDES (Latin grammarian) | DIX, DOROTHEA LYNDE |

| DION | DIX, JOHN ADAMS |

| DIONE | DIXON, GEORGE |

| DIONYSIA | DIXON, HENRY HALL |

| DIONYSIUS (pope) | DIXON, RICHARD WATSON |

| DIONYSIUS (tyrant of Syracuse) | DIXON, WILLIAM HEPWORTH |

| DIONYSIUS AREOPAGITICUS | DIXON |

| DIONYSIUS EXIGUUS | DIZFUL |

| DIONYSIUS HALICARNASSENSIS | DJAKOVO |

| DIONYSIUS PERIEGETES | DLUGOSZ, JAN |

| DIONYSIUS TELMAHARENSIS | DMITRIEV, IVAN IVANOVICH |

| DIONYSIUS THRAX | DNIEPER |

| DIONYSUS | DNIESTER |

| DIOPHANTUS | DOAB |

| DIOPSIDE | DOANE, GEORGE WASHINGTON |

| DIOPTASE | DOBBS FERRY |

| DIORITE | DOBELL, SYDNEY THOMPSON |

| DIP | DÖBELN |

| DIPHENYL | DOBERAN |

| DIPHILUS | DÖBEREINER, JOHANN WOLFGANG |

| DIPHTHERIA | DOBREE, PETER PAUL |

| DIPLODOCUS | DÖBRENTEI, GABOR |

| DIPLOMACY | DOBRITCH |

| DIPLOMATIC | DOBRIZHOFFER, MARTIN |

| DIPOENUS and SCYLLIS | DOBROWSKY, JOSEPH |

| DIPPEL, JOHANN KONRAD | DOBRUDJA |

| DIPSOMANIA | DOBSINA |

| DIPTERA | DOBSON, HENRY AUSTIN |

| DIPTERAL | DOBSON, WILLIAM |

| DIPTYCH | DOCETAE |

| DIR | DOCHMIAC |

| DIRCE | DOCK |

| DIRECT MOTION | DOCK (botany) |

| DIRECTORS | DOCK (marine and river engineering) |

| DIRECTORY | DOCKET |

| DIRGE | DOCK WARRANT |

| DIRK | DOCKYARDS |

| DIRSCHAU | DOCTOR |

| DISABILITY | DOCTORS’ COMMONS |

| DISCHARGE | DOCTRINAIRES |

| DISCHARGING ARCH | DOCUMENT |

| DISCIPLE | DODD, WILLIAM |

| DISCIPLES OF CHRIST | DODDER |

| DISCLAIMER | DODDRIDGE, PHILIP |

| DISCOUNT | DODDS, ALFRED AMÉDÉE |

| DISCOVERY | DODECAHEDRON |

| DISCUS | DODECASTYLE |

| DISINFECTANTS | DÖDERLEIN, JOHANN WILHELM LUDWIG |

| DISMAL | DODGE, THEODORE AYRAULT |

| DISORDERLY HOUSE | DODGSON, CHARLES LUTWIDGE |

| DISPATCH | DODO |

| DISPENSATION | DODONA |

| DISPERSION | DODS, MARCUS |

| D’ISRAELI, ISAAC | DODSLEY, ROBERT |

| DISS | DODSWORTH, ROGER |

275

DINARD, a seaside town of north-western France, in the department of

Ille-et-Vilaine. The town, which is the chief watering-place of

Brittany, is situated on a rocky promontory at the mouth of the Rance

opposite St Malo, which is about 1 m. distant. It is a favourite resort

of English and Americans as well as of the French, its attractions being

the beauty of its situation, the mildness of the climate and the good

bathing. It has two casinos and numerous luxurious hotels and elegant

villas. Together with the adjoining watering-place of St Enogat, Dinard

has a population of 4882 (1906).

DINDIGUL, a town of British India, in the Madura district of Madras, 880

ft. above the sea, 40 m. from Madura by rail. Pop. (1901) 25,182.

Dindigul has risen into importance as the centre of a trade in tobacco

and manufacture of cigars, which are exported to England. There are two

large European cigar factories here. The town has manufactures oe silk,

muslim#and blankets, and an export trade in hides and cardamoms; and

there is a large native Christian population, with two churches. The

ancient fort, well preserved, stands on a rock rising 350 ft. above the

town; this was formerly a position of great strategic importance,

commanding passes into Madura from Coimbatore, and figured prominently

in the military operations of the Mahrattas in the 17th and 18th

centuries, and of Hyder Ali in 1755 seq., being thrice captured by the

British (1767, 1783, 1790). After the two first captures it was restored

to Hyder Ali under treaty; after the third it was ceded to the East

India Company.

KARL WILHELM DINDORF (1802-1883), German classical scholar, was born at

Leipzig on the 2nd of January 1802. From his earliest years he showed a

strong taste for classical studies, and after completing F. Invernizi’s

edition of Aristophanes at an early age, and editing several grammarians

and rhetoricians, was in 1828 appointed extraordinary professor of

literary history in his native city. Disappointed at not obtaining the

ordinary professorship when it became vacant in 1833, he resigned his

post in the same year, and devoted himself entirely to study and

literary work. His attention had at first been chiefly given to

Athenaeus, whom he edited in 1827, and to the Greek dramatists, all of

whom he edited separately and combined in his Poetae scenici Graeci

(1830 and later editions). He also wrote a work on the metres of the

Greek dramatic poets, and compiled special lexicons to Aeschylus and

Sophocles. He edited Procopius for Niebuhr’s Corpus of the Byzantine

writers, and between 1846 and 1851 brought out at Oxford an important

edition of Demosthenes; he also edited Lucian and Josephus for the Didot

classics. His last important editorial labour was his Eusebius of

Caesarea (1867-1871). Much of his attention was occupied by the

republication of Stephanus’s Thesaurus (Paris, 1831-1865), chiefly

executed by him and his brother Ludwig, a work of prodigious labour and

utility. His reputation suffered somewhat through the imposture

practised upon him by the Greek Constantine Simonides, who succeeded in

deceiving him by a fabricated fragment of the Greek historian Uranius.

The book was printed, and a few copies had been circulated, when the

forgery was discovered, just in time to prevent its being given to the

world under the auspices of the university of Oxford. Shortly after the

death of his brother, he lost all his property and his library by rash

speculations. He died on the 1st of August 1883.

His brother Ludwig (1805-1871) was born at Leipzig on the

3rd of January 1805, and died there on the 6th of September 1871.

He never held any academical position, and led so secluded a

life that many doubted his existence, and declared that he was

a mere pseudonym. The important share which he took in the

edition of the Thesaurus is nevertheless authenticated by his

own signature to his contributions. He also published valuable

editions of Polybius, Dio Cassius and other Greek historians.

D’INDY, PAUL-MARIE-THÉODORE-VINCENT (1851- ),

French musical composer, was born in Paris, on the 27th of March

1851. He studied composition and the organ at the Paris Conservatoire

under César Franck, and obtained the grand prize offered

by the city of Paris in 1885 with Le Chant de la Cloche, a dramatic

legend after Schiller. His principal works, beside the above, are

the symphonic trilogy Wallenstein, the symphonic works entitled

Saugefleurie, La Forêt enchantée, Istar, Symphonie sur un air

montagnard français; overture to Anthony and Cleopatra; Ste

Marie Magdeleine, a cantata; Attendez-moi sous l’orme, a one-act

opera; Fervaal, a musical drama in three acts. Vincent d’Indy

is perhaps the most prominent among the disciples of César

Franck. Imbued with very high aims, he was always guided by

a lofty ideal, and few musicians have attained so complete a

mastery over the art of instrumentation. His music, however,

lacks simplicity, and can never become popular in the widest

sense. His opera Fervaal, which is styled “action musicale”, is

constructed upon the system of Leit-motifs. Its legendary

subject recalls both Parsifal and Tristan, and the music is also

suggestive of Wagnerian influence. D’Indy can scarcely be

considered so typical a representative of modern French music as

his juniors Alfred Bruneau, the composer of Le Rêve, L’Attaque du

moulin, Messidor, or Gustave Charpentier, the author of Louise,

who chose subjects of modern life for their operatic works.

DINEIR, a small town in Asia Minor, built amidst the ruins of

Celaenae-Apamea, near the sources of the Maeander (Menderes).

It is the terminus of the Smyrna-Aidin-Dineir railway. Pop.

1400. (See Apamea.)

DINGELSTEDT, FRANZ VON (1814-1881), German poet and

dramatist, was born at Halsdorf, in Hesse Cassel, on the 30th of

June 1814. Having studied at the university of Marburg, he

became in 1836 a master at the Lyceum in Cassel, from which he

was transferred to Fulda in 1838. In 1839 he produced a novel,

Unter der Erde, which obtained considerable success, and in 1841

published the book by which he is best remembered, the Lieder

eines kosmopolitischen Nachtwächters. These poems, animated

as they are by a spirit of bitter opposition to everything that

savours of despotism, were an effective contribution to the

political poetry of the day. The popularity of this book

determined Dingelstedt to take up a literary career, and in 1841

he obtained an appointment on the staff of the Augsburger

allgemeine Zeitung. In 1843, however, the satirist of German

princes accepted, to the general surprise, the appointment of

private librarian to the king of Württemberg, and in the same year

he married the celebrated Bohemian opera singer, Jenny Lutzer.

In 1845 he published a volume of poems, some of which, treating

of modern life, possessed great literary rather than strictly

poetical merit. A subsequent collection, published in 1852,

attracted little attention. The success of his tragedy Das Haus

der Barneveldt (1850) obtained for him the position of intendant

at the court theatre at Munich, where he soon became the centre

of literary society. He incurred, however, the animosity of the

Jesuit clique at the court, and in 1856 was suddenly dismissed on

the most frivolous charges. A similar position was offered to him

at Weimar through the influence of Liszt, and he remained there

until 1867. His administration was most successful, and he

especially distinguished himself by presenting all Shakespeare’s

historical plays upon the stage in an unbroken cycle. In 1867 he

became director of the court opera house in Vienna, and in 1872

of the Hofburgtheater, a position he held until his death on the

15th of May 1881. Among his other works may be noticed an

autobiographical sketch of his Munich career, entitled Münchener

276

Bilderbogen (1879), Die Amazone, an art novel of considerable

merit (1869), translations of several of Shakespeare’s comedies,

and several writings dealing with questions of practical dramaturgy.

He was ennobled in 1867 by the king of Bavaria and in

1876 was created Freiherr by the emperor of Austria.

Dingelstedt’s Sämtliche Werke appeared in 12 vols. (1877-1878),

but this edition is far from complete. On his life see, besides the

autobiography mentioned above, J. Rodenberg, Heimaterinnerungen

an F. Dingelstedt (Berlin, 1882), and by the same author, F. Dingelstedt,

Blätter aus seinem Nachlass (2 vols., 1891). Also an essay by

A. Stern in Zur Literatur der Gegenwart (Leipzig, 1880).

DINGHY, or Dingey (from the Hindu dēngī a small boat, the

diminutive of denga, a sloop or coasting vessel), a boat of greatly

varying size and shape, used on the rivers of India; the term is

applied also, in certain districts, to a larger boat used for coasting

purposes. The name was adopted by the merchantmen trading

with India, and is now generally used to designate the small extra

boat kept for general purposes on a man-of-war or merchant

vessel, and also, on the Thames, for small pleasure boats built for

one or two pairs of sculls.

DINGLE, a seaport and market town of county Kerry, Ireland,

in the west parliamentary division, the terminus of the Tralee

and Dingle railway. Pop. (1901) 1786. This may be considered

the most westerly town in the United Kingdom unless

Knightstown at Valencia Island be excepted; it lies on the south

side of the northernmost of the great promontories which protrude

into the Atlantic on the south-western coast of Ireland, on

the fine natural harbour of Dingle Bay, in a wild hilly district

abundant in relics of antiquity. The town, which is the centre

of a considerable fishing industry, especially in mackerel, was in

the 16th century of no little importance as a seaport; it had also

a noted manufacture of linen. It was incorporated by Queen

Elizabeth, and returned two members to the Irish parliament

until the Union.

DINGO, a name applied apparently by Europeans to the

warrigal, or native Australian dog, the Canis dingo of J. F.

Blumenbach. The dingo is a stoutly-built, rather short-legged,

sandy-coloured dog, intermediate in size between a jackal and a

wolf, and measuring about 51 in. in total length, of which the

tail takes up about eleven. In general appearance it is very like

some of the pariah dogs of India and Egypt; and, except on

distributional grounds, there is no reason for regarding it as

specifically distinct from such breeds. Dingos, which are found

both wild and tame, interbreed freely with European dogs introduced

into the country, and it may be that the large amount

of black on the back of many specimens may be the result of

crossing of this nature.

The main point of interest connected with the dingo relates to

its origin; that is to say, whether it is a member of the indigenous

Australian fauna (among which it is the only large placental

mammal), or whether it has been introduced into the country

by man. There seems to be no doubt that fossilized remains of

the dingo occur intermingled with those of the extinct Australian

mammals, such as giant kangaroos, giant wombats and the still

more gigantic Diprotodon. And since remains of man have

apparently not yet been detected in these deposits, it has been

thought by some naturalists that the dingo must be an indigenous

species. This was the opinion of Sir Frederick McCoy, by whom

the deposits in question were regarded as probably of Pliocene age.

A similar view is adopted by D. Ogilvy in a Catalogue of Australian

Mammals, published at Sydney in 1892; the writer going however

one step further and expressing the belief that the dingo

is the ancestor of all domesticated dogs. The latter contention

cannot for a moment be sustained; and there are also strong

arguments against the indigenous origin of the dingo. That the

animal now occurs in a wild state is no argument whatever as to

its being indigenous, seeing that a domesticated breed introduced

by man into a new country abounding in game would almost

certainly revert to the wild state. The apparent absence of

human remains in the beds yielding dingo teeth and bones (which

are almost certainly not older than the Pleistocene) is of only

negative value, and liable to be upset by new discoveries. Then,

again (as has been pointed out by R. I. Pocock in the first part of

the Kennel Encyclopaedia, 1907), the absence of any really wild

species of the typical group of the genus Canis between Burma

and Siam on the one hand and Australia on the other is a very

strong argument against the dingo being indigenous, seeing that,

whether brought by man or having travelled thither of its own

accord, the dingo must have reached its present habitat by way

of the Austro-Malay archipelago. If it had followed that route

in the course of nature, it is inconceivable that it would not still

be found on some portions of the route. On the supposition that

the dingo was introduced by man, we have now fairly decisive

evidence that the native Australian, in place of being (as formerly

supposed) a member of the negro stock, is a low type of Caucasian

allied to the Veddahs of Ceylon and the Toalas of Celebes.

Consequently the Australian natives must be presumed to have

reached the island-continent by way of Malaya; and if this be

admitted, nothing is more likely than that they should have been

accompanied by pariah dogs of the Indian type. Confirmation of

this is afforded by the occurrence in the mountains of Java of a

pariah-like dog which has reverted to an almost completely wild

condition; and likewise by the fact that the old voyagers met

with dogs more or less similar to the dingo in New Guinea, New

Zealand and the Solomon and certain other of the smaller Pacific

islands. On the whole, then, the most probable explanation of

the case is that the dingo is an introduced species closely allied to

the Indian pariah dog. Whether the latter represents a truly wild

type now extinct, cannot be determined. If so, all pariahs should

be classed with the Australian warrigal under the name of Canis

dingo. If, on the other hand, pariahs, and consequently the dingo,

cannot be separated specifically from the domesticated dogs of

western Europe, then the dingo should be designated Canis

familiaris dingo.

(R. L.*)

DINGWALL, a royal and police burgh and county town of the

shire of Ross and Cromarty, Scotland. Pop. (1901) 2519. It is

situated near the head of Cromarty Firth where the valley of the

Peffery unites with the alluvial lands at the mouth of the Conon,

18½ m. N.W. of Inverness by the Highland railway. Its name,

derived from the Scandinavian Thingvöllr, “field or meeting-place

of the thing,” or local assembly, preserves the Norse origin of

the town; its Gaelic designation is Inverpefferon, “the mouth of

the Peffery.” The 18th-century town house, and some remains

of the ancient mansion of the once powerful earls of Ross still

exist. There is also a public park. An obelisk, 57 ft. high, was

erected over the grave of the 1st earl of Cromarty. The town

belongs to the Wick district group of parliamentary burghs. It is

a flourishing distributing centre and has an important corn market

and auction marts. Some shipping is carried on at the harbour

at the mouth of the Peffery, about a mile below the burgh.

Branch lines of the Highland railway run to Strathpeffer and to

Strome Ferry and Kyle of Lochalsh (for Skye). Alexander II.

created Dingwall a royal borough in 1226, and its charter was

renewed by James IV. On the top of Knockfarrel (Gaelic, cnoc,

hill; faire, watch, or guard), a hill about 3 m. to the west, is a

large and very complete vitrified fort with ramparts.

DINKA (called by the Arabs Jange), a widely spread negro

people dwelling on the right bank of the White Nile to about

12° N., around the mouth of the Babr-el-Ghazal, along the right

bank of that river and on the banks of the lower Sobat. Like the

Shilluk, they were greatly harried from the north by Nuba-Arabic

tribes, but remained comparatively free owing to the vast

extent of their country, estimated to cover 40,000 sq. m., and their

energy in defending themselves. They are a tall race with skins

of almost blue black. The men wear practically no clothes,

married women having a short apron, and unmarried girls a

fringe of iron cones round the waist. They tattoo themselves

with tribal marks, and extract the lower incisors; they also

pierce the ears and lip for the attachment of ornaments, and wear

a variety of feather, iron, ivory and brass ornaments. Nearly

all shave the head, but some give the hair a reddish colour by

moistening it with animal matter. Polygamy is general; some

headmen have as many as thirty or more wives; but six is the

average number. They are great cattle and sheep breeders; the

men tend their beasts with great devotion, despising agriculture,

277

which is left to the women; the cattle are called by means of

drums. Save under stress of famine cattle are never killed

for food, the people subsisting largely on durra. The Dinkas

reverence the cow, and snakes, which they call “brothers.”

Their folklore recognizes a good and evil deity; one of the two

wives of the good deity created man, and the dead go to live with

him in a great park filled with animals of enormous size. The

evil deity created cripples. The Dinka came, in 1899, under the

control of the Sudan government, justice being administered

as far as possible in accord with tribal custom. A compendium

of Dinka laws was compiled by Captain H. D. E. O’Sullivan.

See G. A. Schweinfurth, The Heart of Africa (1874); W. Junker,

Travels in Africa, Eng. edit. (London, 1890-1892); The Anglo-Egyptian

Sudan, edited by Count Gleichen (London, 1905).

DINKELSBÜHL, a town of Germany, in the kingdom of

Bavaria, on the Wörnitz, 16 m. N. from Nördlingen, on the railway

to Dombühl. Pop. 5000. It is an interesting medieval town,

still surrounded by old walls and towers, and has an Evangelical

and two Roman Catholic churches. Notable is the so-called

Deutsches Haus, the ancestral home of the counts of

Drechsel-Deufstetten, a fine specimen of the German renaissance style of

wooden architecture. There are a Latin and industrial school,

several benevolent institutions, and a monument to Christoph

von Schmid (1768-1854), a writer of stories for the young. The

inhabitants carry on the manufacture of brushes, gloves, stockings

and gingerbread, and deal largely in cattle.

Fortified by the emperor Henry I., Dinkelsbühl received in

1305 the same municipal rights as Ulm, and obtained in 1351 the

position of a free imperial city, which it retained till 1802, when

it passed to Bavaria. Its municipal code, the Dinkelsbuhler

Recht, published in 1536, and revised in 1738, contained a very

extensive collection of public and private laws.

DINNER, the chief meal of the day, eaten either in the middle

of the day, as was formerly the universal custom, or in the

evening. The word “dine” comes through Fr. from Med. Lat.

disnare, for disjejunare, to break one’s fast (jejunium); it is,

therefore, the same word as Fr. déjeuner, to breakfast, in

modern France, to take the midday meal, dîner being used

for the later repast. The term “dinner-wagon,” originally

a movable table to hold dishes,

is now used of a two-tier sideboard.

DINOCRATES, a great and

original Greek architect, of the

age of Alexander the Great. He

tried to captivate the ambitious

fancy of that king with a design

for carving Mount Athos into a

gigantic seated statue. This plan

was not carried out, but Dinocrates

designed for Alexander the

plan of the new city of Alexandria,

and constructed the vast

funeral pyre of Hephaestion.

Alexandria was, like Peiraeus

and Rhodes (see Hippodamus),

built on a regular plan; the streets

of most earlier towns being narrow

and confused.

|

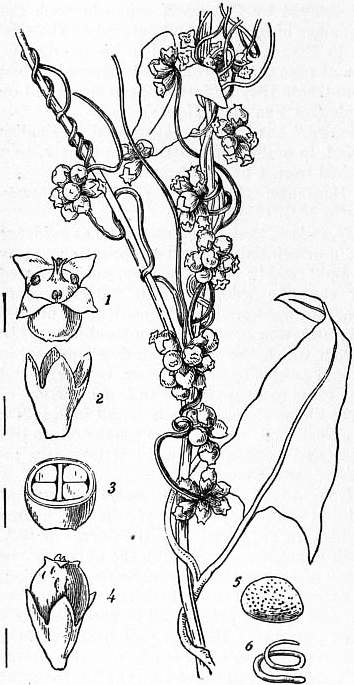

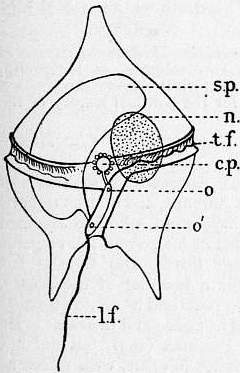

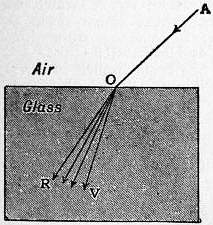

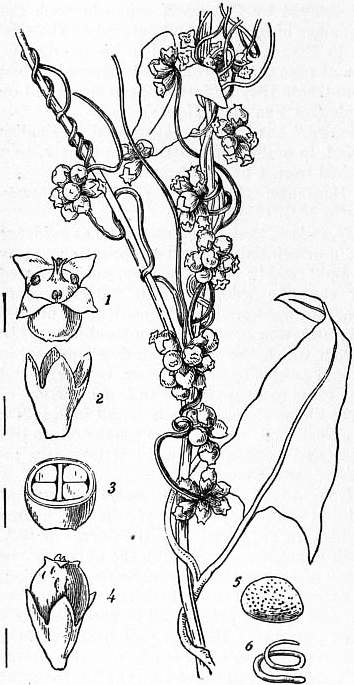

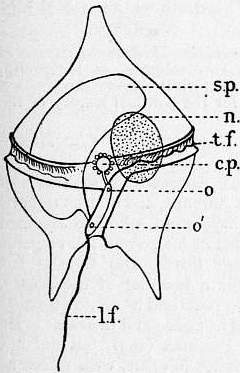

After F. Schutt in Engler and Prantl’s

Pflanzenfamilien, by permission of Wm

Engelmann.

Fig. 1.—Peridinium divergens

showing longitudinal and transverse

grooves in which lie the

respective flagella l.f., t.f.; s.p.,

large “sack pusule” discharging

through a tube by pore o’; c.p.,

“collective pusule discharging

at o, and surrounded by a ring

of formative” or “daughter

pusules”; n, nucleus. |

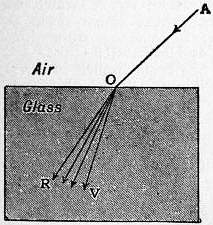

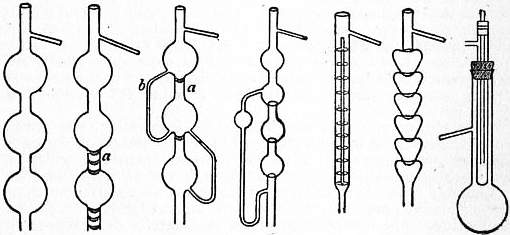

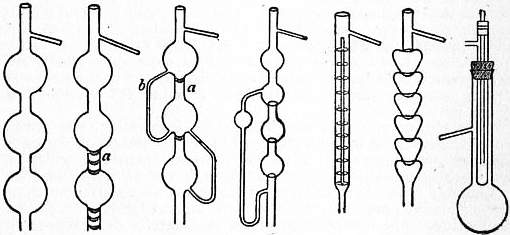

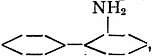

DINOFLAGELLATA, so called

by O. Bütschli (= the Cilioflagellata

of E. Claparide and

H. Lachmann), a group of Protozoa,

characterized as Mastigophora,

provided with two flagella,

the one anterior extended in locomotion,

the other coiled round

its base, or lying in a transverse

groove. The body is bounded by a firm pellicle, often supplemented

by an armour (“lorica”) of cuticular cellulose plates,

with usually a marked longitudinal groove from which the

anterior flagellum springs, and an oblique or spiral transverse

groove for the second flagellum. In Polykrikos (fig. 2, 9) there

are eight transverse grooves each with its flagellum. The

armour-plates are often exquisitely sculptured, and may be

produced into spines or perpendicular plates to give greater

surface extension, as we find in other plankton organisms.

The cortical plasma may protrude pseudopodia in the longitudinal

groove; it contains trichocysts in several species, true

nematocysts in Polykrikos. It contains chromatophores in

many species, coloured by a mixed lipochrome pigment which

appears to be distinct from diatomin. The endoplasm is

ramified between alveoli; it contains a large nucleus (in

Polykrikos there are eight nuclei, accompanied by smaller,

more numerous bodies regarded by O. Butschli as micro-nuclei).

Besides the other spaces are definite rounded or oval

vacuoles with a permanent pellicular wall termed by Schutt

“pusules”; these open by a duct or ducts into the longitudinal

groove. They enlarge and diminish, and are possibly excretory

like the “contractile vacuoles” of other Protista; though it has

been suggested that by their communication with the medium

they subserve nutrition. Nutrition is of course holozoic or

278

saprophytic in the colourless forms, holophytic in the coloured;

but these divergent methods are exhibited by different species

of the same genus, or even by individuals of one and the same

species under different conditions. Binary fission has been

widely observed, both in the active condition or after loss of

the flagella: it differs from that of true Flagellates in not

being longitudinal, but transverse or oblique (fig, 2, 2). Repeated

fission (brood-formation) within a cyst has also been

observed, as in Pyrocystis and Ceratium; and possibly the chains

of Ceratium and other (fig. 2, 5 and 6) genera are due to the non-separation

of the brood-cells. Conjugation of adults has been

observed in several species, the most complete account being that

of Zederbauer on Ceratium hirundinella (marine): either mate

puts forth a tube which meets and opens into that of the

other (as in some species of Chlamydomonas and Desmids); the

two cell-bodies fuse in this tube, and encyst to form a resting

zygospore. The Dinoflagellates are relatively large for

Mastigophora, many attaining 50 µ (1/500”) in length. The

majority are marine; but some genera (Ceratium, Peridinium)

include fresh-water species. Many are highly phosphorescent

and some by their abundance colour the water of the sea or pool

which they dwell in. Like so many coloured Protista, they

frequently possess a pigmented “eye-spot” in which may be

sunk a spheroidal refractive body (“lens”).

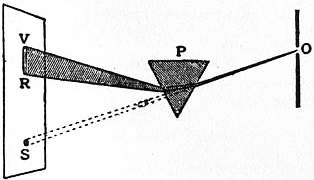

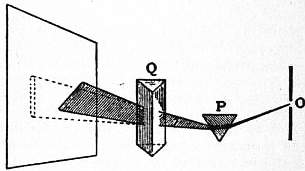

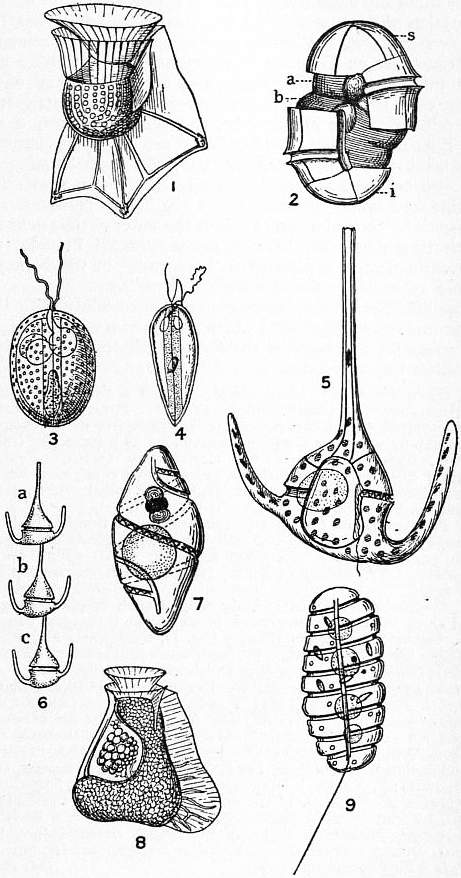

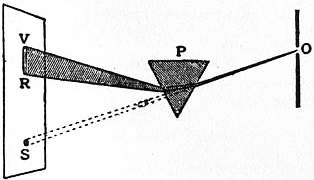

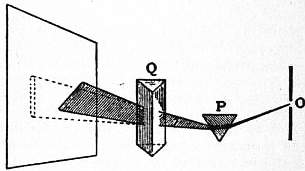

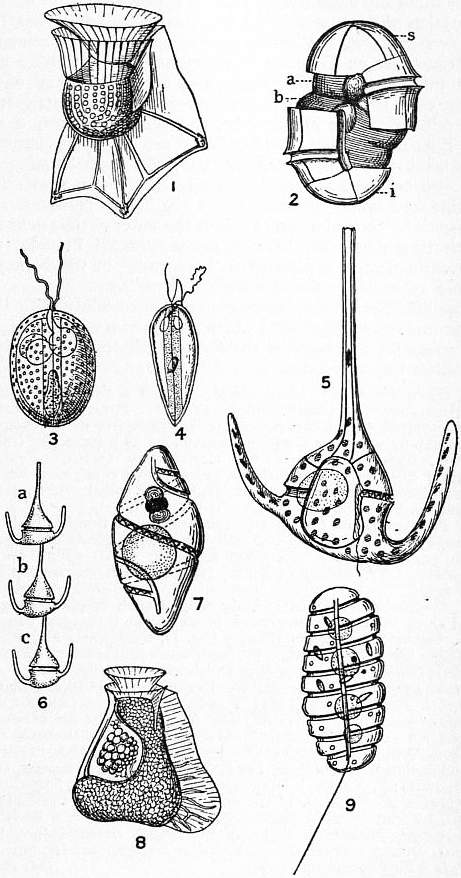

|

| Fig. 2. |

From Delage and Hérouard’s Traité de zoologie concrete,

by permission of Schleicher Frères.

|

1. Modified from Schütt, Ornithoceras.

2. Diagram of transverse fission of a Dinoflagellate.

3. After Schutt, Exuviaeella.

4. After Stein, Prorocentrum. |

5, 6. Ceratium, single and series.

7. Pouchetia fusus (Schutt).

8. Citharistes.

9. After Butschli, Polykrikos. |

The affinities of the Dinoflagellata are certainly with those

Cryptomonadine Flagellates which possess two unequal flagella;

the zoospores or young of the Cystoflagellates are practically

colourless Dinoflagellates.

1. Gymnodiniaceae: body naked, or with a simple cellulose or

gelatinous envelope; both grooves present. Pyrocystis (Murray),

often encysted, spherical or crescentic, becoming free within cyst wall,

and escaping whole or after brood-divisions as a form like Gymnodinium;

Gymnodinium (Stein); Hemidinium (Stein); Pouchetia

(Schütt) (fig. 2, 7) with complex eye-spot; to this group we may

refer Polykrikos (Bütschli) (fig. 2, 9), with its metameric transverse

grooves and flagella.

2. Prorocentraceae (Schütt) ( = the Adinida of Bergh); body surrounded

by a firm shell of two valves without a girdle band; transverse

groove absent; transverse flagellum coiled round base of

longitudinal. Exuviaeella (Cienk.) (fig. 2, 3); Prorocentrum (Ehrb.)

(fig. 2, 4).

3. Peridiniaceae (Schütt); body with a shell of plates, a girdle

band along the transverse groove, in which the transverse flagellum

lies. Genera, Peridinium (Ehrb.) (fig. 1), fresh-water and marine;

Ceratium (Schrank) (fig. 2, 5, 6), fresh-water and marine; Citharistes

(Stein); Ornithoceras (Claparède and Lachmann) (fig. 2, 1).

Literature.—R. S. Bergh, “Der Organismusder Cilioflagellaten,”

Morphol. Jahrbuch, vii. (1881); F. von Stein, Organismus der Infusionsthiere,

Abth. 3, 2. Hälfte; Die Naturgeschichte der arthrodelen

Flagellaten (1883); Bütschli, “Mastigophora” (in Bronn’s Thierreich,

i. Abth. 2), 1881-1887; G. Pouchet, various observations on

Dinoflagellates, Journal de l’anatomie et de la physiologie (1885,

1887, 1891); F. Schütt, “Die Peridineen der Plankton Expedition”

(Ergebnisse d. Pl. Exed. i. Th. vol. iv. 1895); and “Peridiniales”

in Engler and Prantl’s Pflanzenfamilien, vol. i. Abt. 2 b. (1896);

Zederbauer, Berichte d. deutschen botanischen Gesellschaft, vol. xx.

(1900); Delage and Hérouard, Traité de zoologie concrète, vol. i. La

Cellule et les protozoaires (1896).

(M. Ha.)

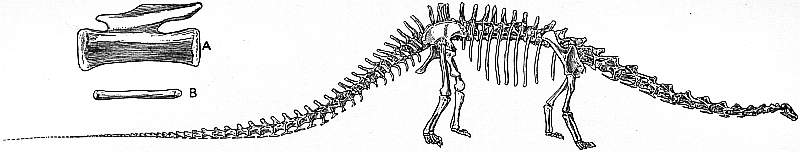

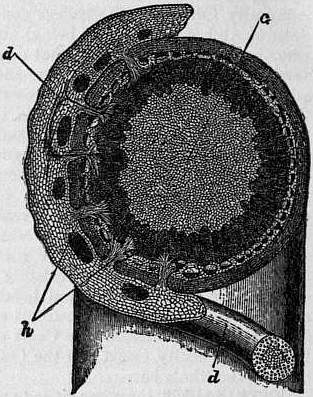

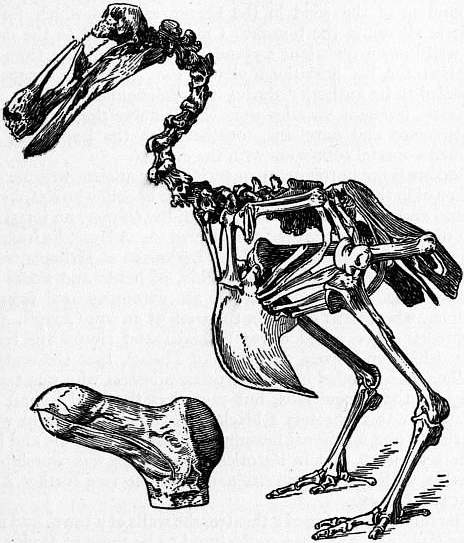

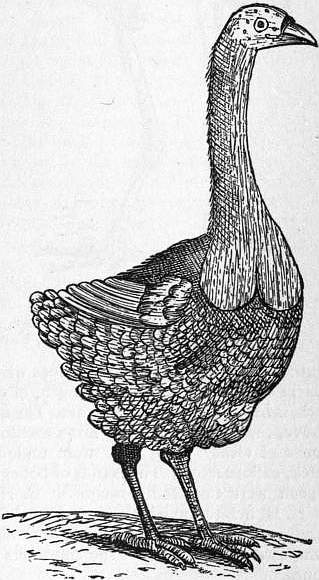

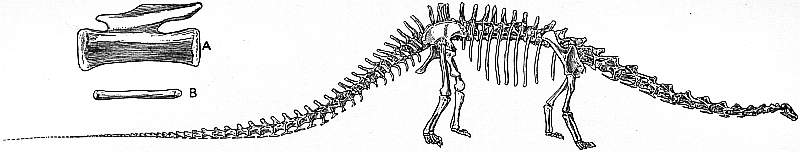

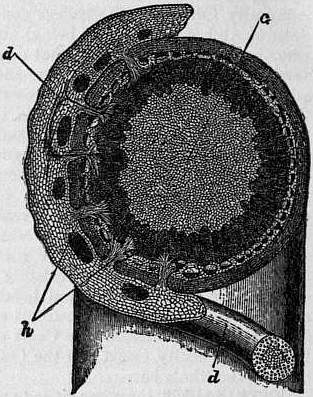

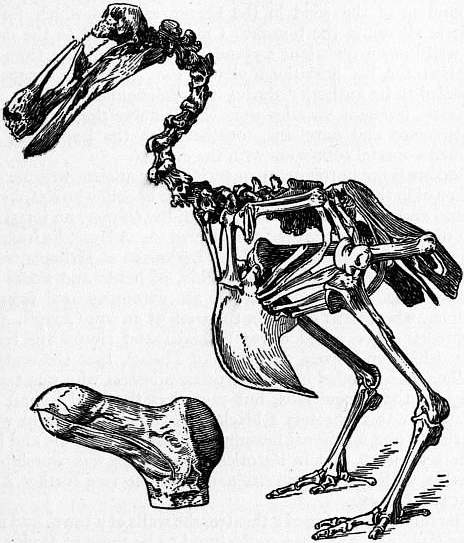

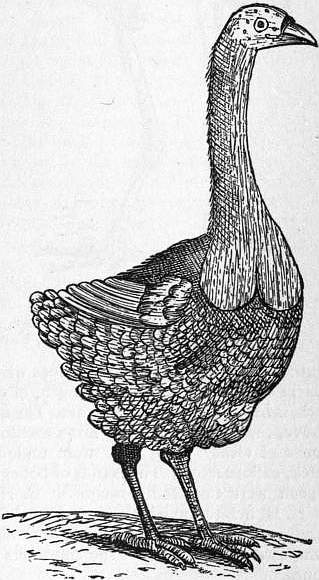

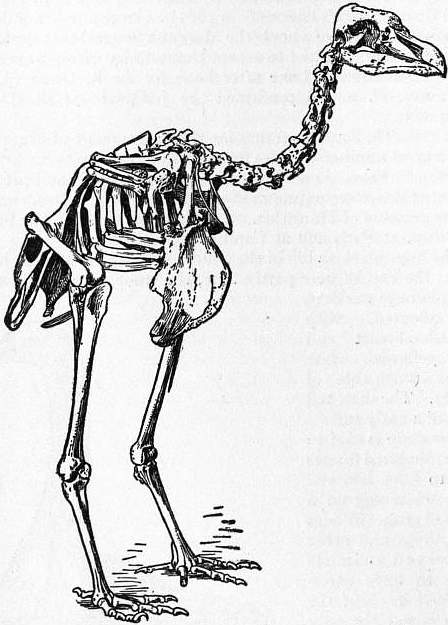

DINOTHERIUM, an extinct mammal, fossil remains of which

occur in the Miocene beds of France, Germany, Greece and

Northern India. These consist chiefly of teeth and the bones of

the head. An entire skull, obtained from the Lower Pliocene

beds of Eppelsheim, Hesse-Darmstadt, in 1836, measured 4½ ft.

in length and 3 ft. in breadth, and indicates an animal exceeding

the elephant in size. The upper jaw is apparently destitute of

incisor and canine teeth, but possesses five molars on each side,

with a corresponding number in the jaw beneath. The most

remarkable feature, however, consists in the front part of the

lower jaw being bent downwards and bearing two tusk-like

incisors also directed downwards and backwards. Dinotherium

is a member of the group Proboscidea, of the line of descent of

the elephants.

DINWIDDIE, ROBERT (1693-1770), English colonial governor

of Virginia, was born near Glasgow, Scotland, in 1693. From the

position of customs clerk in Bermuda, which he held in 1727-1738,

he was promoted to be surveyor-general of the customs “of

the southern ports of the continent of America,” as a reward

for having exposed the corruption in the West Indian customs

service. In 1743 he was commissioned to examine into the

customs service in the Barbadoes and exposed similar corruption

there. In 1751-1758 he was lieutenant-governor of Virginia,

first as the deputy of Lord Albemarle and then, from July 1756 to

January 1758, as deputy for Lord Loudon. He was energetic in

the discharge of his duties, but aroused much animosity among

the colonists by his zeal in looking after the royal quit-rents, and

by exacting heavy fees for the issue of land-patents. It was his

chief concern to prevent the French from building in the Ohio

Valley a chain of forts connecting their settlements in the north

with those on the Gulf of Mexico; and in the autumn of 1753 he

sent George Washington to Fort Le Bœuf, a newly established

French post at what is now Waterford, Pennsylvania, with a

message demanding the withdrawal of the French from English

territory. As the French refused to comply, Dinwiddie secured

from the reluctant Virginia assembly a grant of £10,000 and in the

spring of 1754 he sent Washington with an armed force toward

the forks of the Ohio river “to prevent the intentions of the

French in settling those lands.” In the latter part of May

Washington encountered a French force at a spot called Great

Meadows, near the Youghiogheny river, in what is now south-western

Pennsylvania, and a skirmish followed which precipitated

the French and Indian War. Dinwiddie was especially active at

this time in urging the co-operation of the colonies against the

French in the Ohio Valley; but none of the other governors,

except William Shirley of Massachusetts, was then much concerned

about the western frontier, and he could accomplish very

little. His appeals to the home government, however, resulted in

the sending of General Edward Braddock to Virginia with two

regiments of regular troops; and at Braddock’s call Dinwiddie

and the governors of Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania

and Maryland met at Alexandria, Virginia, in April 1755, and

planned the initial operations of the war. Dinwiddie’s administration

was marked by a constant wrangle with the assembly over

money matters; and its obstinate resistance to military appropriations

caused him in 1754 and 1755 to urge the home government

to secure an act of parliament compelling the colonies

to raise money for their protection. In January 1758 he left

Virginia and lived in England until his death on the 27th of July

1770 at Clifton, Bristol.

The Official Records of Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant-Governor of

Virginia (1751-1758), published in two volumes, at Richmond,

Va., in 1883-1884, by the Virginia Historical Society, and edited

by R. A. Brock, are of great value for the political history of the

colonies in this period.

DIO CASSIUS (more correctly Cassius Dio), Cocceianus

(c. a.d. 150-235), Roman historian, was born at Nicaea in

Bithynia. His father was Cassius Apronianus, governor of

Dalmatia and Cilicia under Marcus Aurelius, and on his mother’s

side he was the grandson of Dio Chrysostom, who had assumed

the surname of Cocceianus in honour of his patron the emperor

Cocceius Nerva. After his father’s death, Dio Cassius left

Cilicia for Rome (180) and became a member of the senate.

During the reign of Commodus, Dio practised as an advocate at

the Roman bar, and held the offices of aedile and quaestor. He

was raised to the praetorship by Pertinax (193), but did not

assume office till the reign of Septimius Severus, with whom he

was for a long time on the most intimate footing. By Macrinus

he was entrusted with the administration of Pergamum and

Smyrna; and on his return to Rome he was raised to the

consulship about 220. After this he obtained the proconsulship

of Africa, and again on his return was sent as legate successively

to Dalmatia and Pannonia. He was raised a second time to

the consulship by Alexander Severus, in 229; but on the plea

of ill health soon afterwards retired to Nicaea, where he died.

Before writing his history of Rome (῾Ρωμαικά or ῾Ρωμαικὴ Ίστορία), Dio Cassius had dedicated to the emperor Severus

an account of various dreams and prodigies which had

presaged his elevation to the throne (perhaps the Ένόδια

attributed to Dio by Suidas), and had also written a biography

of his fellow-countryman Arrian. The history of Rome, which

279

consisted of eighty books,—and, after the example of Livy, was

divided into decades,—began with the landing of Aeneas in Italy,

and was continued as far as the reign of Alexander Severus

(222-235). Of this great work we possess books 36-60, containing

the history of events from 68 b.c.-a.d. 47; books 36 and

55-60 are imperfect. We also have part of 35 and 36-80 in the

epitome of John Xiphilinus, an 11th-century Byzantine monk.

For the earlier period the loss of Dio’s work is partly supplied

by the history of Zonaras, who followed him closely. Numerous

fragments are also contained in the excerpts of Constantine

Porphyrogenitus. Dio’s work is a most important authority for

the history of the last years of the republic and the early empire.

His industry was great and the various important offices he held

afforded him ample opportunities for historical investigation.

His style, though marred by Latinisms, is clearer than that of

his model Thucydides, and his narrative shows the hand of the

practised soldier and politician; the language is correct and

free from affectation. But he displays a superstitious regard

for miracles and prophecies; he has nothing to say against the

arbitrary acts of the emperors, which he seems to take as a matter

of course; and his work, although far more than a mere compilation,

is not remarkable for impartiality, vigour of judgment or

critical historical faculty.

The best edition with notes is that of H. S. Reimar (1750-1752),

new ed. by F. G. Sturz (1824-1836); text by I. Melber (1890 foll.),

with account of previous editions, and U. P. Boissevain (1895-1901);

translation by H. B. Foster (Troy, New York, 1905 foll.), with full

bibliography; see also W. Christ, Geschichte der griechischen Litteratur

(1898), p. 675; E. Schwartz in Pauly-Wissowa’s Realencyclopadie,

iii. pt. 2 (1899); C. Wachsmuth, Einleitung in das Studium der alten

Geschichte (1895).

DIOCESE (formed on Fr. diocèse, in place of the Eng. form

diocess—current until the 19th century—from Lat. dioecesis,

med. Lat. variant diocesis, from Gr. διοίκησις, “housekeeping,”

“administration,” διοικεῖν, “to keep house,” “to

govern”), the sphere of a bishop’s jurisdiction. In this, its

sole modern sense, the word diocese (dioecesis) has only been

regularly used since the 9th century, though isolated instances of

such use occur so early as the 3rd, what is now known as a diocese

having been till then usually called a parochia (parish). The

Greek word διοίκησις, from meaning “administration,” came

to be applied to the territorial circumscription in which administration

was exercised. It was thus first applied e.g. to the

three districts of Cibyra, Apamea and Synnada, which were added

to Cilicia in Cicero’s time (between 56 and 50 b.c.). The word

is here equivalent to “assize-districts” (Tyrrell and Purser’s

edition of Cicero Epist. ad fam. iii. 8. 4; xiii. 67; cf. Strabo

xiii. 628-629). But in the reorganization of the empire, begun

by Diocletian and completed by Constantine, the word “diocese”

acquired a more important meaning, the empire being divided

into twelve dioceses, of which the largest—Oriens—embraced

sixteen provinces, and the smallest—Britain—four (see Rome:

Ancient History; and W. T. Arnold, Roman Provincial Administration,

pp. 187, 194-196, which gives a list of the dioceses and

their subdivisions). The organization of the Christian church in

the Roman empire following very closely the lines of the civil

administration (see Church History), the word diocese, in its

ecclesiastical sense, was at first applied to the sphere of jurisdiction,

not of a bishop, but of a metropolitan.1 Thus Anastasius

Bibliothecarius (d. c. 886), in his life of Pope Dionysius, says that

he assigned churches to the presbyters, and established dioceses

(parochiae) and provinces (dioeceses). The word, however, survived

in its general sense of “office” or “administration,” and

it was even used during the middle ages for “parish” (see Du

Cange, Glossarium, s. “Dioecesis” 2).

The practice, under the Roman empire, of making the areas of

ecclesiastical administration very exactly coincide with those of

the civil administration, was continued in the organization of the

church beyond the borders of the empire, and many dioceses to

this day preserve the limits of long vanished political divisions.

The process is well illustrated in the case of English bishoprics.

But this practice was based on convenience, not principle; and

the limits of the dioceses, once fixed, did not usually change with

the changing political boundaries. Thus Hincmar, archbishop

of Reims, complains that not only his metropolitanate (dioecesis)

but his bishopric (parochia) is divided between two realms under

two kings; and this inconvenient overlapping of jurisdictions

remained, in fact, very common in Europe until the readjustments

of national boundaries by the territorial settlements of the

19th century. In principle, however, the subdivision of a diocese,

in the event of the work becoming too heavy for one bishop,

was very early admitted, e.g. by the first council at Lugo in Spain

(569), which erected Lugo into a metropolitanate, the consequent

division of diocese being confirmed by the king of the second

council, held in 572. Another reason for dividing a diocese, and

establishing a new see, has been recognized by the church as

duly existing “if the sovereign should think fit to endow some

principal village or town with the rank and privileges of a

city” (Bingham, lib. xvii. c. 5). But there are canons for the

punishment of such as might induce the sovereign so to erect

any town into a city, solely with the view of becoming bishop

thereof. Nor could any diocese be divided without the consent

of the primate.

In England an act of parliament is necessary for the creation of

new dioceses. In the reign of Henry VIII. six new dioceses were

thus created (under an act of 1539); but from that time onward

until the 19th century they remained practically unchanged.

The Ecclesiastical Commissioners Act 1836, which created two

new dioceses (Ripon and Manchester), remodelled the state of the

old dioceses by an entirely new adjustment of the revenues and

patronage of each see, and also extended or curtailed the parishes

and counties in the various jurisdictions.

By the ancient custom of the church the bishop takes his title,

not from his diocese, but from his see, i.e. the place where his

cathedral is established. Thus the old episcopal titles are all

derived from cities. This tradition has been broken, however, by

the modern practice of bishops in the United States and the

British colonies, e.g. archbishop of the West Indies, bishop of

Pennsylvania, Wyoming, &c. (see Bishop).

See Hinschius, Kirchenrecht, ii. 38, &c.; Joseph Bingham, Origines

ecclesiasticae, 9 vols. (1840); Du Cange, Glossarium, s. “Dioecesis”;

New English Dictionary (Oxford, 1897), s. “Diocese.”

1 For exceptions see Hinschius ii. p. 39, note 1.

DIO CHRYSOSTOM (c. a.d. 40-115), Greek sophist and

rhetorician, was born at Piusa (mod. Brusa), a town at the foot

of Mount Olympus in Bithynia. He was called Chrysostom

(“golden-mouthed”) from his eloquence, and also to distinguish

him from his grandson, the historian Dio Cassius; his surname

Cocceianus was derived from his patron, the emperor Cocceius

Nerva. Although he did much to promote the welfare of his

native place, he became so unpopular there that he migrated to

Rome, but, having incurred the suspicion of Domitian, he was

banished from Italy. With nothing in his pocket but Plato’s

Phaedo and Demosthenes’ De falsa legatione, he wandered about

in Thrace, Mysia, Scythia and the land of the Getae. He

returned to Rome on the accession of Nerva, with whom and

his successor Trajan he was on intimate terms. During this

period he paid a visit to Prusa, but, disgusted at his reception,

he went back to Rome. The place and date of his death are

unknown; it is certain, however, that he was alive in 112, when

the younger Pliny was governor of Bithynia.

Eighty orations, or rather essays on political, moral and

philosophical subjects, have come down to us under his name;

the Corinthiaca, however, is generally regarded as spurious, and

is probably the work of Favorinus of Arelate. Of the extant

orations the following are the most important:—Borysthenitica

(xxxvi.), on the advantages of monarchy, addressed to the

inhabitants of Olbia, and containing interesting information on the

history of the Greek colonies on the shores of the Black Sea;

Olympica (xii.), in which Pheidias is represented as setting forth

the principles which he had followed in his statue of Zeus, one

passage being supposed by some to have suggested Lessing’s

Laocoon; Rhodiaca (xxxi.), an attack on the Rhodians for altering

the names on their statues, and thus converting them into

memorials of famous men of the day (an imitation of Demosthenes’

280

Leptines); De regno (i.-iv.), addressed to Trajan, a eulogy of the

monarchical form of government, under which the emperor is the

representative of Zeus upon earth; De Aeschylo et Sophocle et

Euripide (lii.), a comparison of the treatment of the story of

Philoctetes by the three great Greek tragedians; and Philoctetes

(lix.), a summary of the prologue to the lost play by Euripides.

In his later life, Dio, who had originally attacked the philosophers,

himself became a convert to Stoicism. To this period belong the

essays on moral subjects, such as the denunciation of various

cities (Tarsus, Alexandria) for their immorality. Most pleasing

of all is the Euboica (vii.), a description of the simple life of the

herdsmen and huntsmen of Euboea as contrasted with that of the

inhabitants of the towns. Troica (xi.), an attempt to prove to

the inhabitants of Ilium that Homer was a liar and that Troy was

never taken, is a good example of a sophistical rhetorical exercise.

Amongst his lost works were attacks on philosophers and

Domitian, and Getica (wrongly attributed to Dio Cassius by

Suïdas), an account of the manners and customs of the Getae, for

which he had collected material on the spot during his banishment.

The style of Dio, who took Plato and Xenophon especially

as his models, is pure and refined, and on the whole free from

rhetorical exaggeration. With Plutarch he played an important

part in the revival of Greek literature at the end of the 1st

century of the Christian era.

Editions: J. J. Reiske (Leipzig, 1784); A. Emperius (Brunswick,

1844); L. Dindorf (Leipzig, 1857), H. von Arnim (Berlin, 1893-1896).

The ancient authorities for his life are Philostratus, Vit. Soph.

i. 7; Photius, Bibliotheca, cod. 209; Suidas, s.v.; Synesius, Δίων.

On Dio generally see H. von Arnim, Leben und Werke des Dion von

Prusa (Berlin, 1898); C. Martha, Les Moralistes sous l’empire romain

(1865); W. Christ, Geschichte der griechischen Litteratur (1898),

§ 520; J. E. Sandys, History of Classical Scholarship (2nd ed., 1906);

W. Schmid in Pauly-Wissowa’s Realencyclopädie, v. pt. 1 (1905).

The Euboica has been abridged by J. P. Mahaffy in The Greek World

under Roman Sway (1890), and there is a translation of Select Essays

by Gilbert Wakefield (1800).

DIOCLETIAN (Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus)

(a.d. 245-313), Roman emperor 284-305, is said to have been

born at Dioclea, near Salona, in Dalmatia. His original name

was Diocles. Of humble origin, he served with high distinction

and held important military commands under the emperors

Probus and Aurelian, and accompanied Carus to the Persian War.

After the death of Numerianus he was chosen emperor by the

troops at Chalcedon, on the 17th of September 284, and slew with

his own hands Arrius Aper, the praefect of the praetorians. He

thus fulfilled the prediction of a druidess of Gaul, that he would

mount a throne as soon as he had slain a wild boar (aper). Having

been installed at Nicomedia, he received general acknowledgment

after the murder of Carinus. In consequence of the rising of

the Bagaudae in Gaul, and the threatening attitude of the German

peoples on the Rhine, he appointed Maximian Augustus in 286;

and, in view of further dangers and disturbances in the empire,

proclaimed Constantius Chlorus and Galerius Caesars in 293. Each

of the four rulers was placed at a separate capital—Nicomedia,

Mediolanum (Milan), Augusta Trevirorum (Trier), Sirmium.

This amounted to an entirely new organization of the empire, on

a plan commensurate with the work of government which it now

had to carry on. At the age of fifty-nine, exhausted with labour,

Diocletian abdicated his sovereignty on the 1st of May 305, and

retired to Salona, where he died eight years afterwards (others

give 316 as the year of his death). The end of his reign was

memorable for the persecution of the Christians. In defence of

this it may be urged that he hoped to strengthen the empire by

reviving the old religion, and that the church as an independent

state over whose inner life at least he possessed no influence,

appeared to be a standing menace to his authority. Under

Diocletian the senate became a political nonentity, the last traces

of republican institutions disappeared, and were replaced by

an absolute monarchy approaching to despotism. He wore the

royal diadem, assumed the title of lord, and introduced a complicated

system of ceremonial and etiquette, borrowed from the

East, in order to surround the monarchy and its representative

with mysterious sanctity. But at the same time he devoted

his energies to the improvement of the administration of the

empire; he reformed the standard of coinage, fixed the price

of provisions and other necessaries of daily life, remitted the

tax upon inheritances and manumissions, abolished various

monopolies, repressed corruption and encouraged trade. In

addition, he adorned the city with numerous buildings, such

as the thermae, of which extensive remains are still standing

(Aurelius Victor, De Caesaribus, 39; Eutropius ix. 13; Zonaras

xii. 31).

See A. Vogel, Der Kaiser Diocletian (Gotha, 1857), a short sketch,

with notes on the authorities; T. Preuss, Kaiser Diocletian und seine

Zeit (Leipzig, 1869); V. Casagrandi, Diocleziano (Faenza, 1876);

H. Schiller, Gesch. der römischen Kaiserzeit, ii. (1887); T. Bernhardt,

Geschichte Roms von Valerian bis zu Diocletians Tod (1867); A. J.

Mason, The Persecution of Diocletian (1876); P. Allard, La Persécution

de Dioclétien (1890); V. Schultze in Herzog-Hauck’s Realencyklopädie

für protestantische Theologie, iv. (1898); Gibbon. Decline

and Fall, chaps. 13 and 16; A. W. Hunzinger, Die Diocletianische

Staatsreform (1899); O. Seeck, “Die Schatzungsordnung Diocletians”

in Zeitschrift für Social- und Wirthschaftsgeschichte (1896),

a valuable paper with notes containing references to sources; and

O. Seeck, Geschichte des Untergangs der antiken Welt, vol. i. cap. 1.

On his military reforms see T. Mommsen in Hermes, xxiv., and on his

tariff system, Diocletian, Edict of.

DIOCLETIAN, EDICT OF (De pretiis rerum venalium), an imperial

edict promulgated in a.d. 301, fixing a maximum price for

provisions and other articles of commerce, and a maximum rate of

wages. Incomplete copies of it have been discovered at various

times in various places, the first (in Greek and Latin) in 1709, at

Stratonicea in Caria, by W. Sherard, British consul at Smyrna,

containing the preamble and the beginning of the tables down to

No. 403. This partial copy was completed by W. Bankes in 1817.

A second fragment (now in the museum at Aix in Provence) was

brought from Egypt in 1809; it supplements the preamble by

specifying the titles of the emperors and Caesars and the number

of times they had held them, whereby the date of publication can

be accurately determined. For other fragments and their localities

see Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (iii., 1873, pp. 801 and 1055;

and supplement i, 1893, p. 1909); special mention may be made

of those of Elatea, Plataea and Megalopolis. Latin being the

official language all over the empire, there was no official Greek

translation (except for Greece proper), as is shown by the variations

in those portions of the text of which more than one Greek

version is extant. Further, all the fragments come from the

provinces which were under the jurisdiction of Diocletian, from

which it is argued that the edict was only published in the

eastern portion of the empire; certainly the phrase universo orbi

in the preamble is against this, but the words may merely be an

exaggerated description of Diocletian’s special provinces, and if it

had been published in the western portion as well, it is curious

that no traces have been found of it. The articles mentioned

in the edict, which is chiefly interesting as giving their relative

values at the time, include cereals, wine, oil, meat, vegetables,

fruits, skins, leather, furs, foot-gear, timber, carpets, articles of

dress, and the wages range from the ordinary labourer to the

professional advocate. The unit of money was the denarius, not

the silver, but a copper coin introduced by Diocletian, of which

the value has been fixed approximately at 1⁄5th of a penny. The

punishment for exceeding the prices fixed was death or deportation.

The edict was a well-intended but abortive attempt, in

great measure in the interests of the soldiers, to meet the distress

caused by several bad harvests and commercial speculation. The

actual effect was disastrous: the restrictions thus placed upon

commercial freedom brought about a disturbance of the food

supply in non-productive countries, many traders were ruined,

and the edict soon fell into abeyance.

See Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum, vii., a contemporary

who, as a Christian, writes with natural bias against Diocletian;

T. Mommsen, Das Edict Diocletians (1851); W. M. Leake, An Edict

of Diocletian (1826); W. H. Waddington, L’Édit de Dioclétien (1864),

and E. Lépaulle, L’Édit de maximum (1886), both containing introductions

and ample notes; J. C. Rolfe and F. B. Tarbell in Papers

of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, v. (1892)

(Plataea); W. Loring in Journal of Hellenic Studies, xi. (1890)

(Megalopolis); P. Paris in Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, ix.

(1885) (Elatea). There is an edition of the whole by Mommsen, with

notes by H. Blümner (1893).

281

DIODATI, GIOVANNI (1576-1649), Swiss Protestant divine,

was born at Geneva on the 6th of June 1576, of a noble family

originally belonging to Lucca, which had been expatriated on

account of its Protestantism. At the age of twenty-one he was

nominated professor of Hebrew at Geneva on the recommendation

of Theodor Beza. In 1606 he became professor of theology, in

1608 pastor, or parish minister, at Geneva, and in the following

year he succeeded Beza as professor of theology. As a preacher

he was eloquent, bold and fearless. He held a high place among

the reformers of Geneva, by whom he was sent on a mission to

France in 1614. He had previously visited Italy, and made the

acquaintance of Paolo Sarpi, whom he endeavoured unsuccessfully

to engage in a reformation movement. In 1618-1619 he

attended the synod of Dort, and took a prominent part in its

deliberations, being one of the six divines appointed to draw up

the account of its proceedings. He was a thorough Calvinist, and

entirely sympathized with the condemnation of the Arminians.

In 1645 he resigned his professorship, and died at Geneva on the

3rd of October 1649. Diodati is chiefly famous as the author of

the translation of the Bible into Italian (1603, edited with notes,

1607). He also undertook a translation of the Bible into French,

which appeared with notes in 1644. Among his other works are

his Annotationes in Biblia (1607), of which an English translation

(Pious and Learned Annotations upon the Holy Bible) was

published in London in 1648, and various polemical treatises,

such as De fictitio Pontificiorum Purgatorio (1619); De justa

secessione Reformatorum ab Ecclesia Romana (1628); De

Antichristo, &c. He also published French translations of

Sarpi’s History of the Council of Trent, and of Edwin Sandys’s

Account of the State of Religion in the West.

DIODORUS CRONUS (4th century b.c.), Greek philosopher of

the Megarian school. Practically nothing is known of his life.

Diogenes Laërtius (ii. 111) tells a story that, while staying at the

court of Ptolemy Soter, Diodorus was asked to solve a dialectical

subtlety by Stilpo. Not being able to answer on the spur of the

moment, he was nicknamed Κρόνος (the God, equivalent to

“slowcoach”) by Ptolemy. The story goes that he died of

shame at his failure. Strabo, however, says (xiv. 658; xvii. 838)

that he took the name from Apollonius, his master. Like the rest

of the Megarian school he revelled in verbal quibbles, proving that

motion and existence are impossible. His was the famous

sophism known as the Κυριεύων. The impossible cannot

result from the possible; a past event cannot become other than

it is; but if an event, at a given moment, had been possible, from

this possible would result something impossible; therefore the

original event was impossible. This problem was taken up by

Chrysippus, who admitted that he could not solve it. Apart

from these verbal gymnastics, Diodorus did not differ from

the Megarian school. From his great dialectical skill he earned

the title ὁ διαλεκτικός, or διαλεκτικώτατος, a title which was

borne by his five daughters, who inherited his ability.

See Cicero, De Fato, 6, 7, 9; Aristotle, Metaphysica, θ 3; Sext.

Empiric., adv. Math. x. 85; Ritter and Preller, Hist. philos. Gr. et

Rom. chap. v. §§ 234-236 (ed. 1869); and bibliography appended

to article Megarian School.

DIODORUS SICULUS, Greek historian, born at Agyrium in

Sicily, lived in the times of Julius Caesar and Augustus. From

his own statements we learn that he travelled in Egypt between

60-57 b.c. and that he spent several years in Rome. The latest

event mentioned by him belongs to the year 21 b.c. He asserts

that he devoted thirty years to the composition of his history, and

that he undertook frequent and dangerous journeys in prosecution

of his historical researches. These assertions, however, find

little credit with recent critics. The history, to which Diodorus

gave the name βιβλιοθήκη ἱστορική (Bibliotheca historica,

“Historical Library”), consisted of forty books, and was divided

into three parts. The first treats of the mythic history of the non-Hellenic,

and afterwards of the Hellenic tribes, to the destruction

of Troy; the second section ends with Alexander’s death; and

the third continues the history as far as the beginning of Caesar’s

Gallic War. Of this extensive work there are still extant only the

first five books, treating of the mythic history of the Egyptians,

Assyrians, Ethiopians and Greeks; and also the 11th to the 20th

books inclusive, beginning with the second Persian War, and ending

with the history of the successors of Alexander, previous to

the partition of the Macedonian empire (302). The rest exists

only in fragments preserved in Photius and the excerpts of

Constantine Porphyrogenitus. The faults of Diodorus arise

partly from the nature of the undertaking, and the awkward form

of annals into which he has thrown the historical portion of his

narrative. He shows none of the critical faculties of the historian,

merely setting down a number of unconnected details. His

narrative contains frequent repetitions and contradictions, is

without colouring, and monotonous; and his simple diction,

which stands intermediate between pure Attic and the colloquial

Greek of his time, enables us to detect in the narrative the

undigested fragments of the materials which he employed. In

spite of its defects, however, the Bibliotheca is of considerable

value as to some extent supplying the loss of the works of older

authors, from which it is compiled. Unfortunately, Diodorus

does not always quote his authorities, but his general sources of

information were—in history and chronology, Castor, Ephorus

and Apollodorus; in geography, Agatharchides and Artemidorus.

In special sections he followed special authorities—e.g. in the

history of his native Sicily, Philistus and Timaeus.

Editio princeps, by H. Stephanus (1559); of other editions the

best are: P. Wesseling (1746), not yet superseded; L. Dindorf

(1828-1831); (text) L. Dindorf (1866-1868, revised by F. Vogel,

1888-1893 and C. T. Fischer, 1905-1906). The standard works on

the sources of Diodorus are C. G. Heyne, De fontibus et auctoribus

historiarum Diodori, printed in Dindorf’s edition, and C. A.

Volquardsen, Die Quellen der griechischen und sicilischen Geschichten

bei Diodor (1868); A. von Mess, Rheinisches Museum (1906); see

also L. O. Bröcker, Untersuchungen über Diodor (1879), short, but

containing much information; O. Maass, Kleitarch und Diodor

(1894- ); G. J. Schneider, De Diodori fontibus, i.-iv. (1880);

C. Wachsmuth, Einleitung in das Studium der alten Geschichte (1895);

Greece; Ancient History, “Authorities.”

DIODOTUS, Seleucid satrap of Bactria, who rebelled against

Antiochus II. (about 255) and became the founder of the Graeco-Bactrian

kingdom (Trogus, Prol. 41; Justin xli. 4, 5, where he is

wrongly called Theodotus; Strabo xi. 515). His power seems to

have extended over the neighbouring provinces. Arsaces, the

chieftain of the nomadic (Dahan) tribe of the Parni, fled before

him into Parthia and here became the founder of the Parthian

kingdom (Strabo l.c.). When Seleucus II. in 239 attempted to

subjugate the rebels in the east he seems to have united with him

against the Parthians (Justin xli. 4, 9). Soon afterwards he died

and was succeeded by his son Diodotus II., who concluded a peace

with the Parthians (Justin l.c.). Diodotus II. was killed by

another usurper, Euthydemus (Polyb. xi. 34, 2). Of Diodotus I.

we possess gold and silver coins, which imitate the coins of

Antiochus II.; on these he sometimes calls himself Soter, “the

saviour.” As the power of the Seleucids was weak and continually

attacked by Ptolemy II., the eastern provinces and

their Greek cities were exposed to the invasion of the nomadic

barbarians and threatened with destruction (Polyb. xi. 34, 5);

thus the erection of an independent kingdom may have been a

necessity and indeed an advantage to the Greeks, and this epithet

well deserved. Diodotus Soter appears also on coins struck in his

memory by the later Graeco-Bactrian kings Agathocles and

Antimachus. Cf. A. v. Sallet, Die Nachfolger Alexanders d. Gr.

in Baktrien und Indien; Percy Gardner, Catal. of the Coins of the

Greek and Scythian Kings of Bactria and India (Brit. Mus.); see

also Bactria.

(Ed. M.)

DIOGENES, “the Cynic,” Greek philosopher, was born at

Sinope about 412 b.c., and died in 323 at Corinth, according to

Diogenes Laërtius, on the day on which Alexander the Great died

at Babylon. His father, Icesias, a money-changer, was imprisoned

or exiled on the charge of adulterating the coinage. Diogenes was

included in the charge, and went to Athens with one attendant,

whom he dismissed, saying, “If Manes can live without Diogenes,

why not Diogenes without Manes?” Attracted by the ascetic

teaching of Antisthenes, he became his pupil, despite the brutality

with which he was received, and rapidly excelled his master both

in reputation and in the austerity of his life. The stories which

282

are told of him are probably true; in any case, they serve

to illustrate the logical consistency of his character. He inured

himself to the vicissitudes of weather by living in a tub belonging

to the temple of Cybele. The single wooden bowl he possessed he

destroyed on seeing a peasant boy drink from the hollow of his

hands. On a voyage to Aegina he was captured by pirates and

sold as a slave in Crete to a Corinthian named Xeniades. Being

asked his trade, he replied that he knew no trade but that of

governing men, and that he wished to be sold to a man who

needed a master. As tutor to the two sons of Xeniades, he lived

in Corinth for the rest of his life, which he devoted entirely to

preaching the doctrines of virtuous self-control. At the Isthmian

games he lectured to large audiences who turned to him from

Antisthenes. It was, probably, at one of these festivals that he

craved from Alexander the single boon that he would not stand

between him and the sun, to which Alexander replied “If I were

not Alexander, I would be Diogenes.” On his death, about which

there exist several accounts, the Corinthians erected to his

memory a pillar on which there rested a dog of Parian marble.

His ethical teaching will be found in the article Cynics (q.v.).

It may suffice to say here that virtue, for him, consisted in

the avoidance of all physical pleasure; that pain and hunger

were positively helpful in the pursuit of goodness; that all the

artificial growths of society appeared to him incompatible with

truth and goodness; that moralization implies a return to nature

and simplicity. He has been credited with going to extremes of

impropriety in pursuance of these ideas; probably, however, his

reputation has suffered from the undoubted immorality of some of

his successors. Both in ancient and in modern times, his personality

has appealed strongly to sculptors and to painters. Ancient

busts exist in the museums of the Vatican, the Louvre and the

Capitol. The interview between Diogenes and Alexander is represented

in an ancient marble bas-relief found in the Villa Albani.

Rubens, Jordaens, Steen, Van der Werff, Jeaurat, Salvator Rosa

and Karel Dujardin have painted various episodes in his life.

The chief ancient authority for his life is Diogenes Laërtius vi. 20;

see also Mayor’s notes on Juvenal, Satires, xiv. 305-314; and article

Cynics.

DIOGENES APOLLONIATES (c. 460 b.c.), Greek natural

philosopher, was a native of Apollonia in Crete. Although of

Dorian stock, he wrote in the Ionic dialect, like all the physiologi

(physical philosophers). There seems no doubt that he lived some

time at Athens, where it is said that he became so unpopular

(probably owing to his supposed atheistical opinions) that his

life was in danger. The views of Diogenes are transferred in the

Clouds (264 ff.) of Aristophanes to Socrates. Like Anaximenes,

he believed air to be the one source of all being, and all other

substances to be derived from it by condensation and rarefaction.

His chief advance upon the doctrines of Anaximenes is that

he asserted air, the primal force, to be possessed of intelligence—“the

air which stirred within him not only prompted, but instructed.

The air as the origin of all things is necessarily an

eternal, imperishable substance, but as soul it is also necessarily

endowed with consciousness.” In fact, he belonged to the old

Ionian school, whose doctrines he modified by the theories of

his contemporary Anaxagoras, although he avoided his dualism.

His most important work was Περὶ φύσεως (De natura), of

which considerable fragments are extant (chiefly in Simplicius);

it is possible that he wrote also Against the Sophists and On the

Nature of Man, to which the well-known fragment about the

veins would belong; possibly these discussions were subdivisions

of his great work.

Fragments in F. Mullach, Fragmenta philosophorum Graecorum,

i. (1860); F. Panzerbieter, Diogenes Apolloniates (1830), with

philosophical dissertation; J. Burnet, Early Greek Philosophy (1892);

H. Ritter and L. Preller, Historia philosophiae (4th ed., 1869),

§§ 59-68; E. Krause, Diogenes von Apollonia (1909). See Ionian

School.

DIOGENES LAËRTIUS (or Laërtius Diogenes), the

biographer of the Greek philosophers, is supposed by some to have

received his surname from the town of Laërte in Cilicia, and by

others from the Roman family of the Laërtii. Of the circumstances

of his life we know nothing. He must have lived after

Sextus Empiricus (c. a.d. 200), whom he mentions, and before

Stephanus of Byzantium (c. a.d. 500), who quotes him. It is

probable that he flourished during the reign of Alexander Severus

(a.d. 222-235) and his successors. His own opinions are equally

uncertain. By some he was regarded as a Christian; but it seems

more probable that he was an Epicurean. The work by which

he is known professes to give an account of the lives and sayings

of the Greek philosophers. Although it is at best an uncritical

and unphilosophical compilation, its value, as giving us an insight

into the private life of the Greek sages, justly led Montaigne

to exclaim that he wished that instead of one Laërtius there had

been a dozen. He treats his subject in two divisions which he

describes as the Ionian and the Italian schools; the division is

quite unscientific. The biographies of the former begin with

Anaximander, and end with Clitomachus, Theophrastus and

Chrysippus; the latter begins with Pythagoras, and ends with

Epicurus. The Socratic school, with its various branches, is

classed with the Ionic; while the Eleatics and sceptics are

treated under the Italic. The whole of the last book is devoted to

Epicurus, and contains three most interesting letters addressed

to Herodotus, Pythocles and Menoeceus. His chief authorities

were Diocles of Magnesia’s Cursory Notice (Έπιδρομή) of Philosophers

and Favorinus’s Miscellaneous History and Memoirs.

From the statements of Burlaeus (Walter Burley, a 14th-century

monk) in his De vita et moribus philosophorum the text of

Diogenes seems to have been much fuller than that which we

now possess. In addition to the Lives, Diogenes was the author

of a work in verse on famous men, in various metres.

Bibliography.—Editio princeps (1533); H. Hübner and C.

Jacobitz with commentary (1828-1833); C. G. Cobet (1850), text

only. See F. Nietzsche, “De Diogenis Laërtii fontibus” in

Rheinisches Museum, xxiii., xxiv. (1868-1869); J. Freudenthal,

“Zu Quellenkunde Diog. Laërt.,” in Hellenistische Studien, iii.

(1879); O. Maass, De biographis Graecis (1880); V. Egger, De

fontibus Diog. Laërt. (1881). There is an English translation by

C. D. Yonge in Bohn’s Classical Library.

DIOGENIANUS, of Heraclea on the Pontus (or in Caria), Greek

grammarian, flourished during the reign of Hadrian. He was

the author of an alphabetical lexicon, chiefly of poetical words,

abridged from the great lexicon (Περὶ γλωσσῶν) of Pamphilus

of Alexandria (fl. a.d. 50) and other similar works. It was also

known by the title Περιεργοπένητες (for the use of “industrious

poor students”). It formed the basis of the lexicon, or rather

glossary, of Hesychius of Alexandria, which is described in the

preface as a new edition of the work of Diogenianus. We still

possess a collection of proverbs under his name, probably an

abridgment of the collection made by himself from his lexicon

(ed. by E. Leutsch and F. W. Schneidewin in Paroemiographi

Graeci, i. 1839). Diogenianus was also the author of an Anthology

of epigrams, of treatises on rivers, lakes, fountains and promontories;

and of a list (with map) of all the towns in the world.

DIOGNETUS, EPISTLE TO, one of the early Christian apologies.

Diognetus, of whom nothing is really known, has expressed

a desire to know what Christianity really means—“What is this

new race” of men who are neither pagans nor Jews? “What is

this new interest which has entered into men’s lives now and not

before?” The anonymous answer begins with a refutation of

the folly of worshipping idols, fashioned by human hands and

needing to be guarded if of precious material. The repulsive

smell of animal sacrifices is enough to show their monstrous

absurdity. Next Judaism is attacked. Jews abstain from

idolatry and worship one God, but they fall into the same error of

repulsive sacrifice, and have absurd superstitions about meats

and sabbaths, circumcision and new moons. So far the task is

easy; but the mystery of the Christian religion “think not to

learn from man.” A passage of great eloquence follows, showing

that Christians have no obvious peculiarities that mark them off

as a separate race. In spite of blameless lives they are hated.

Their home is in heaven, while they live on earth. “In a word,

what the soul is in a body, this the Christians are in the

world.... The soul is enclosed in the body, and yet itself

holdeth the body together: so Christians are kept in the world

as in a prison-house, and yet they themselves hold the world

283

together.” This strange life is inspired in them by the almighty

and invisible God, who sent no angel or subordinate messenger to

teach them, but His own Son by whom He created the universe.

No man could have known God, had He not thus declared

Himself. “If thou too wouldst have this faith, learn first the

knowledge of the Father. For God loved men, for whose sake He

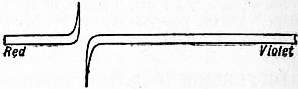

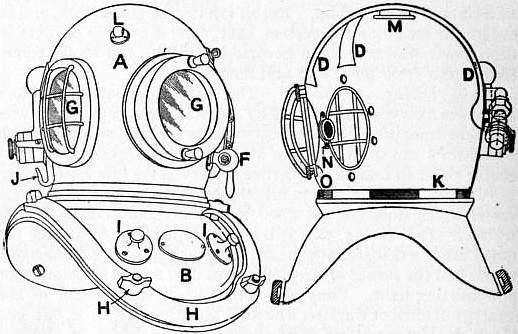

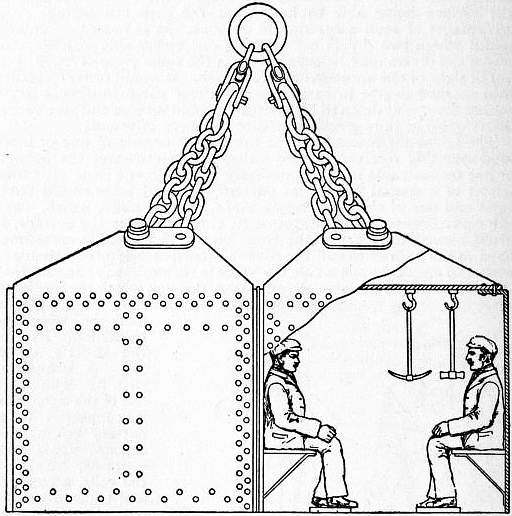

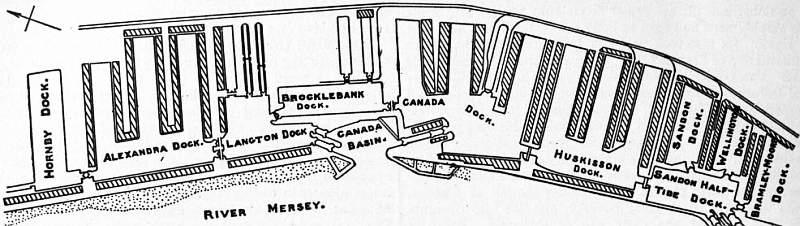

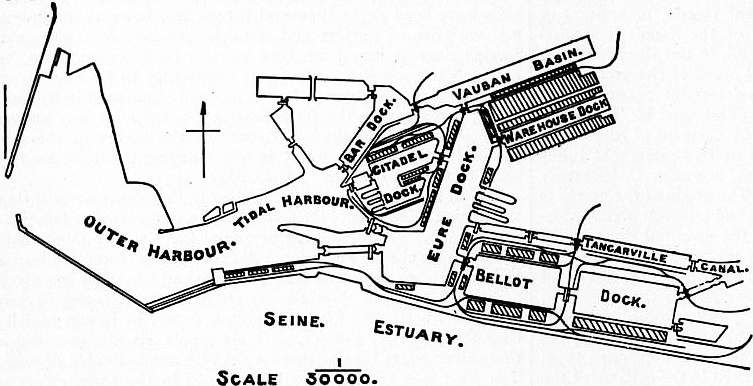

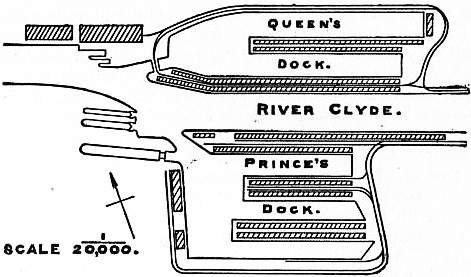

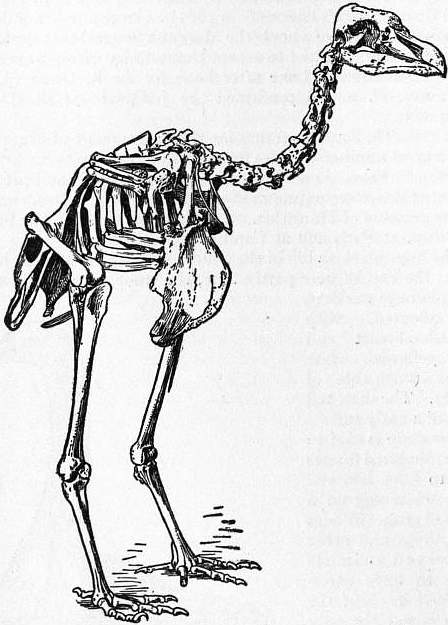

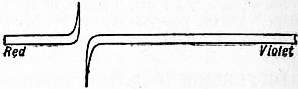

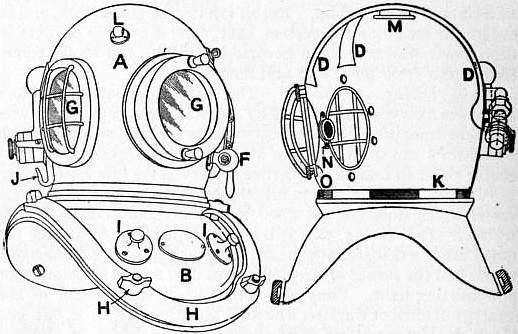

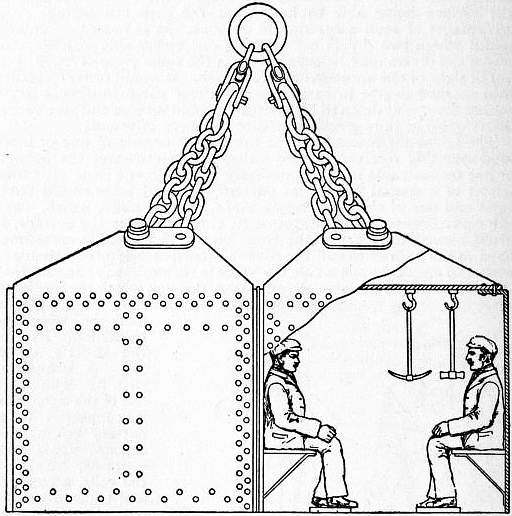

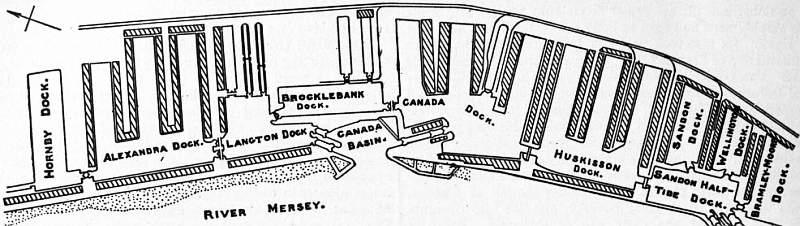

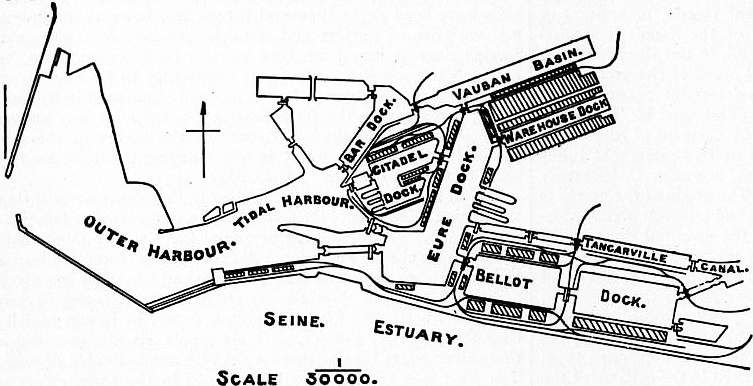

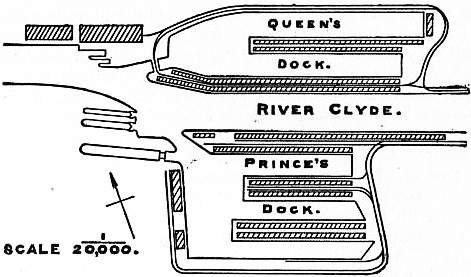

made the world.... Knowing Him, thou wilt love Him and imitate