The Project Gutenberg EBook of For John's Sake, by Annie Frances Perram

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

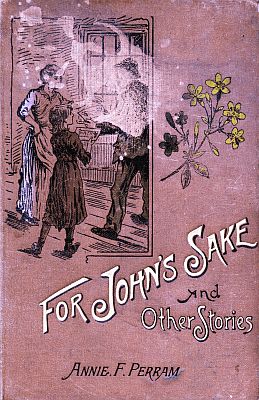

Title: For John's Sake

and Other Stories.

Author: Annie Frances Perram

Release Date: March 26, 2010 [EBook #31785]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOR JOHN'S SAKE ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Lindy Walsh, Emmy and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Frontispiece.

Frontispiece.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Well, Ruthie."

"Master's just rung, and he says he wants you and me to come upstairs together."

"What for, I wonder! Don't look so troubled, little woman;" and John, the well-built, broad-shouldered gardener, looked up with an unmistakable glance of affection at the somewhat clouded face of Ruth, the trim, neat parlour-maid, who had come into the conservatory to bring him the message from the dining-room. "I'll just wash my hands and be ready in a minute," he continued, following her into the kitchen. With much inward trepidation, Ruth,[2] accompanied by John, entered the dining-room a few minutes later.

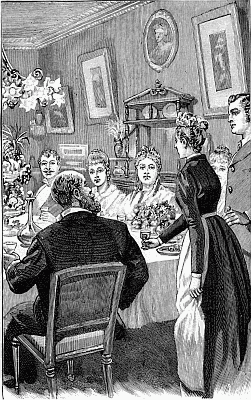

Mr. and Mrs. Groombridge, their eldest son, who was a medical student; three daughters, and one or two younger boys were seated at the nearly finished dessert.

"Well, John, I dare say you wonder why we sent for you and Ruth; but the fact is, your mistress heard from cook this morning a piece of news which you have been sly enough to keep from us," said Mr. Groombridge. Ruth blushed violently, and withdrew a little behind John's burly figure.

"There's nothing to be ashamed of, Ruth; indeed, you've every reason to be proud and happy," added Mr. Groombridge, with a kind look and kinder tone. There was no mistaking the assent that was visible in Ruth's shy uplifted eyes. She was proud and happy, and she involuntarily moved a step nearer to John.

"We thought you would like to know, John," continued his master, "how really glad we are that you and Ruth have settled this little affair between you. You have both been good, faithful servants, and deserve to be 'happy ever after,' as the story-books say. Now we want to drink to your health and future happiness, and you must drink with us."

Mr. Groombridge poured out two glasses of wine, and handed them to John and Ruth.

"Your health and happiness, John and Ruth," he said, draining his own glass.[3]

"Your health and happiness, John and Ruth," repeated his wife and children, with their glasses to their lips.

"And when I go in for matrimony, John, may my choice be as wise as yours," added the eldest son, whose partiality for Ruth was no secret.

"No doubt you would like to choose some one who would be as ready as Ruth to fly at your beck and call, and think nothing too great a trouble to do for you, Master Harry," saucily remarked his younger sister Kate, in an aside.

"Hush, my dear; little girls of sixteen know nothing about such serious things," gravely responded Harry. Kate tossed her head, and was about to reply, when John spoke:

"I'm sure, sir," he began, "that Ruth and me owe our best thanks to you and mistress for your kindness in wishing us well, and if I may be bold enough to say so, sir, we find it our pleasure as well as our duty, to try and please so good and kind a master and mistress, and here's to your health and happiness for many a long day, and the young ladies', and Mr. Harry's too." And having performed a duty for himself and Ruth, John tossed off his wine in much the same fashion as his master.

"Come, Ruth, drink your wine," said Mrs. Groombridge, perceiving that the girl's glass remained untouched.

"Drink it, Ruth," said John in an undertone.[4]

"Come, don't be bashful, Ruth, we are all your friends," said Harry encouragingly. But Ruth advanced to the table, and with trembling hands put her full glass down. The rich colour that had dyed her cheeks a few minutes before had gone, and she was white to the lips, but her voice was firm as she answered:

"Please, ma'am, I can't drink it."

"Not drink it! Why not, Ruth?"

"Because, ma'am, as soon as I was engaged to John, I signed the pledge, and determined I would never touch any intoxicating drink again."

Mr. Groombridge raised his eyebrows, and Harry gave a low whistle of astonishment.

"What a queer fancy! Perhaps you won't have any objection to giving your reason for taking such a step," said Mrs. Groombridge, with a slight hauteur of manner.

"Because—because,"—said Ruth hesitating, and then desperately proceeding; "because, ma'am, I want to do the best for John that I can, and I mean him to have a happy home, and never any reason to be ashamed of me." Ruth stopped suddenly.

"Well, well, that is very good and creditable, of course, but what has it all to do with not touching intoxicants?" impatiently asked Mr. Groombridge.

"Oh, sir, it has everything to do with it. If you knew what I do about the misery and want that has come to happy hearts and homes, just because the[5] wife had got into the habit of taking too much drink, you would think so too. You know, sir, I was brought up in the town, and couldn't help seeing the curse that drink is. Sometimes the husband was the drinker, and sometimes both of them; and there was scarce a home about us that hadn't been ruined by drink; and so I made up my mind that if ever I had a home of my own, I would do my part towards keeping it free from such a curse, and for John's sake, I have signed the pledge, and for John's sake I must keep it, sir. I hope you and mistress will forgive me for refusing your wine."

"Bravo, Ruth! you're a brick," cried Harry.

"Be quiet, my son," said his father, adding: "Well, Ruth, I honour your motive, but there are one or two points that I can't see at all. Surely, if you are moderate in your use of stimulant, it would be a blessing, and not a curse, for it is only the excessive use of intoxicants which render them so harmful."

"I can't argue about it, sir. I only know that every man and woman who is going down to a drunkard's grave was once moderate in the use of stimulants, and never had a thought of taking too much. I know that there are many who are never anything but moderate drinkers; but there's danger somewhere, and because I can't rightly say where it comes in, and perhaps shouldn't know when it did, I've put myself out of the way of it altogether."[6]

"That's woman's logic all the world over; but I would like to know why you cannot just for once take a glass of wine. You know it's good, and quite unlike the wretched stuff that ruins so many."

"I've promised not to take any kind of intoxicating drink, and I dare not break my promise, sir," said Ruth firmly.

Mr. Groombridge shrugged his shoulders and rose from the table.

"Wait a minute, John," he said, "we haven't heard what you think of this fancy of Ruth's."

"To tell the truth, I don't approve of it, sir. It's as good as saying that she hasn't any faith in herself, and expected to go to the bad, if she wasn't bound by a promise she'd put her name to," answered John in a tone of dissatisfaction.

"My views, exactly, John; besides, it's setting her judgment against yours, which I wouldn't think of allowing, even at this early juncture," said Mr. Groombridge, with a serio-comic expression.

"Oh, father, you wouldn't think of allowing, indeed, when only a few minutes ago, you declared that mother's judgment was ever so much better than yours, and that ever since you had known her, you had trusted to it more than to your own," cried Kate.

"My dear, your remark is quite irrelevant," and Mr. Groombridge dismissed the inconvenient topic with John and Ruth.

"Don't be angry with me, John; I couldn't do[7] anything else," timidly said Ruth, as she followed John back to the conservatory.

"I'm not pleased with you, Ruth, I must say. I should like the woman I have chosen to have so much self respect that she would feel it impossible to stoop to degrade herself, as you seem to think you could easily do."

"Oh, John, I thought you would understand me better than that, for you know so much more than I could tell master and mistress. Why, John, don't you know how the curse of drink blighted my own home, and made my early years a misery? Can I ever forget the nightly horror when my mother staggered home to rouse the neighbourhood with her drunken shouts and blasphemies? Can I forget the dear little ones I nursed while they pined away to sink into untimely graves? Can I forget my father's life-long bitterness and premature end? And if I could forget these things, how could I forget the dying despair, the loathing of her sin, and yet the unconquerable craving of disease that held my poor mother captive through her last hours!"

"Dear Ruthie, hush; don't recall those memories. A brighter life is before you, and all I blame you for is because you imagine that without binding yourself you might follow in your mother's footsteps."

"That is where you are wrong, John," said Ruth, looking up at him with sorrowful eyes: "At my age my mother was no more a slave to drink than I am. She[8] only took it in moderation, and if any one had suggested to her that she was in danger of becoming an habitual drinker, she would have been indignant. It was only because she found that a little stimulant revived her, when she was weak and ailing, that she began to take it frequently, till by and bye the habit became so strong, that though she tried hard to break it she could not, and why should I be stronger than my own mother?"

"Well, darling, have it your own way. I shall not alter my opinion of you; but I won't argue the point. Now, dry your eyes, and be happy;" and being an obedient woman, Ruth dismissed her tears, and smiled up at John.

"Ruth," said John presently; "how is it that you are afraid for yourself, and yet not afraid for me?"

"Oh, John, I couldn't be; I trust you entirely, and though you know how much I would like you to become an abstainer too, not a thought of danger crosses my mind when you refuse."

"I should be sorry and hurt if you felt otherwise, my dear, and you may continue to trust me. I could never disgrace myself and bring more sorrow to you," and John took Ruth's hand, and held his head up proudly, and looked every inch of him a man worthy of a woman's trust and devotion.

"Oh, I'm so sorry, I can't even ask to be spared. It's Jane's evening out, and we've got company, and there's hot supper ordered."

"What a nuisance! Ask Jane to give up for once; you're always obliging her."

"No, I can't do that, John, for cook is not best pleased, and Jane doesn't go the way to manage her."

"I'll go and give cook the length of my tongue, I declare," said John, angrily.

"Now you'll do nothing of the sort. You'll go and spend the evening with your brother, and give him my kind regards, and be sure and bring me back all the news." So saying, Ruth gave John a bright decided nod, and whisked back into the kitchen.[10]

"What do you think of that, cook? the unreasonableness of men!"

"What's up now?" asked cook, who was bending with a gloomy face over preparations for an elaborate supper.

"Why, John wanted me to go home with him to-night, and didn't see why I couldn't, though I told him how busy we should be."

"It's quite enough to have one of you gadding out and filling my hands with your work," growled cook.

"Yes, it's too bad, but we'll manage well enough without Jane; let me help you mix that, now," and Ruth took the basin, and with deft fingers, which cook secretly admired, beat the compound it contained till it was pronounced "just the thing."

Notwithstanding her brightness and ready surrender of an evening's pleasure, Ruth watched John go off with a keen feeling of disappointment, and for some minutes there was silence in the room.

"She's worth a dozen Janes," said cook to herself, for she was not so wholly engrossed with her own pursuits as to be quite unobservant of Ruth's disappointment.

"I don't know how it is," thought Ruth, as the busy evening wore away; "cook and I do get on well together; she's quite pleasant to-night, and wasn't cross, though I took the wrong sauce in just now."

Ah, Ruth, if there were more sunny tempers and[11] unclouded faces like yours in the world, there would oftener come to clouded minds and gloomy moods just such brightness as you have brought to your fellow-servant to-night!

John's brother Dick was several years older than John. Some ten years previously he had taken to a seafaring life, but soon tiring of it, he had settled in Australia. We say settled, but Dick Greenwood was one of those men who could never be truly said to settle to anything. He had tried farming, but the work was too hard; then he had joined a party going into the bush, their free and easy life having an attraction for him. After that, he went into a city store, and just as he had mastered the details of the business and might have succeeded in it, he was charmed by the performances of a band of travelling actors, and not being without natural ability in that direction, he had induced them to accept his services, and now, with little money, and a great deal of shady experience, he had worked his passage back to England, that he might just see how things were looking in the old country.

"Well, Jack, my boy, how are you?" he said in a loud, hoarse voice, as John entered the room, which was redolent of tobacco and brandy.

"All right, Dick; glad to see you, though I shouldn't have known you again. My word, you're a little different to the thin lath of a fellow you were when you left home."[12]

"You may say so," cried Dick; "I was a poor milksop then, and no mistake; but I've improved, and, you bet, I've learned a thing or two."

John was not quite so sure of the improvement. At least the stripling who had left his father's home was fresh and pure looking, but the man who had returned in his place was bloated and pimpled, and his once frank eyes now wandered furtively about.

"John's grown a fine fellow, hasn't he, Dick?" asked the mother, proudly.

"He ain't bad-looking, if that's what you mean, but he don't look up to snuff. No offence, Jack. I'll teach you a few wrinkles. Have a pipe, boy."

"Thanks," said John, replenishing his own.

"Take a glass," and Dick made a bumper of hot spirit and pushed it towards his brother.

"I don't take spirit, Dick. A glass of ale now and then is enough for me."

"Stuff and nonsense, Jack. Take it like a man. There's nothing like a glass of brandy and water for putting life into a fellow."

John took the glass, with a twinge of conscience as he thought of Ruth. But in the excitement of his brother's stirring accounts of bush life everything else was forgotten, and he not only drained the spirit before him, but finished a second glass with which Dick slyly supplied him.

"I tell you, Jack," said his brother, at the close of the evening, "life in England is a slow-going, humbugging[13] sort of thing; hard work and little pay; you've got to bow and scrape to those who've got the brass, and they lord it over you as they don't dare to do anywhere else. Now, where I've come from, Jack's as good as his master, and in as fair a way of making his fortune too. Take my advice, boy, and come back with me. In a year or two you'll have made a home for that bonny lass I've been hearing of, and you can send for her. What do you say, eh?"

For a minute John was too surprised to speak. "Really, Dick, you've taken me unawares. I'd like to get on faster than I have been doing, and make a better home for my little woman than I've any prospect of doing here; but for all that, what you propose is too serious a step to think of taking without a deal of thought, and I don't know what Ruth would say."

"If the girl's got any grit in her, she'll say, 'go, by all means, and send for me as quick as you can.' You can work your passage out, and I could get you into a store at Melbourne, and you're such a sticker, you'd be sure to get on. Now I never expect to be a rich man; I can't plod, and I must have change; but you're different, and would soon make your fortune."

John bade his parents and brother good-night, and walked home revolving the new idea. It was surrounded by a halo of romance that rendered it increasingly attractive to him. Success and happiness seemed to lay within his easy reach, and by the time[14] that he arrived at his master's house he had quite decided to accompany his brother back to Australia, if Ruth would only consent to follow him.

"And she's such a loving, sensible little thing; she wouldn't wish to stand in my way for a moment, especially when she knows it is for her own sake I want to go."

So thinking, John let himself in through the garden door, and was not surprised to find a dark figure, with white cap and apron, standing on the kitchen doorstep waiting for him.

"You are late, John; cook and Jane have gone to bed."

"Well, Ruthie, I'm glad of that, because if you're not too tired, I want a chat with you."

Too tired, indeed! When all the evening Ruth had been looking forward to that few minutes as her ample compensation for the disappointments and worries she had borne so patiently.

"Why, yes, dear, I believe so; but Dick put so many new ideas into my head that I didn't know how the time passed," replied John, wondering how he should speak of his new plans to Ruth.

"What sort of ideas, John?"

"He's been talking of Australia, and saying there's no place like it for getting on in the world, and, of course, he's likely to know; and, Ruthie, dear, he said if I would go back with him, he'd put me in the way of making money, and getting a home ready for you in no time."

Ruth took her hand out of John's, and stared fixedly into the fire.[16]

"Can't you say something, Ruth?" asked John, after waiting several minutes. Ruth breathed hard.

"What do you say, John? Do you want to go?"

"I don't want to leave you, darling, but if you'd promise to come out to me, I think it would be a good thing for both of us. I could get on so much better, and we could marry so much quicker than if I plodded on at the rate I'm going now."

"Then," said Ruth, looking up with a brave smile upon her white face, "you must go, John, and when you send for me I'll come out to you."

"Bless you, my dear, brave girl, you shall never repent your decision," cried John. "I'll work harder than ever, and we'll soon be together again, never to say good-bye."

But at that dread word, Ruth's composure gave way, and she hid her face.

"Don't take on so, Ruthie. It will only be a short separation, and we're bound to each other for life," said John, trying to soothe her.

"I've no fear in letting you go from me, John," answered Ruth, proudly, through her tears; "and after you're once gone, I shall look forward to seeing you again." And the lump in Ruth's throat was choked back, and she sat up with an air that was plainly intended to carry a warning to any rebellious tears that might threaten.

"And now, John, tell me about your brother. Is he like you?"[17]

John laughed.

"I'm afraid you wouldn't think so, Ruthie, and I can't say Australia has much improved him. However, you must judge for yourself, for I shall take you to see him soon. He sent kind messages to you, and is anxious to make your acquaintance."

But Dick was soon dismissed from the conversation, for Ruth and John had much to talk over that was of far more interest even than a brother newly arrived from the other side of the world. Before they parted that night, John had succeeded in imparting to Ruth a little of his own enthusiasm in view of the new life he was about to enter upon, though her last thought before closing her weary eyes in sleep was: "Women feel so differently from men, and I must try and not discourage John by any of my fears, poor boy!"

A few days later she accompanied John to his home.

"Dick's out, my dear, but he'll be in directly, as he knew you were coming," said Mrs. Greenwood, affectionately greeting Ruth.

"He don't care to spend much of his time with his old father and mother, Dick don't," complained Mr. Greenwood.

"We can hardly expect he'd settle down to our quiet ways, father, such a boy for company as he is. John's different now, and he'll be sure to make a comfortable stay-at-home husband; but then he hasn't the go in him that my Dick has."[18]

"He's quite sufficient, anyhow," said Ruth quickly, with an instinctive feeling of dislike towards the brother who she felt must be so different to John. Truly, as the door opened just then, and Dick's ungainly figure appeared, the contrast between the brothers was striking. Ruth's inward comment was not complimentary, but she struggled with herself, and when John said by way of introduction, "Dick, I've brought Ruthie to see you," she stretched out her hand with no hesitation of manner.

"Glad to see you, my lass. Jack's a more knowing dog than I thought for, I declare," he exclaimed, looking at Ruth's sweet, upturned face with such coarse approbation, that the girl's eyes fell under his scrutiny.

"Guess I may claim a brother's right a little beforehand," continued Dick, trying to draw Ruth to him.

Ruth's eyes flashed, and she started back indignantly, saying: "Indeed, you shall do no such thing, Mr. Richard."

"Come, come, Dick, Ruth isn't the girl to allow any liberty," interposed John, putting Ruth into a chair.

"Prudish, eh? Ah, well, colonial life will soon knock that rubbish out of her," returned Dick, in an unpleasant tone.

"So you're really bent on going as well, John?" asked his mother, anxiously.[19]

"Well, yes, mother; Ruth says she'll come after me, and I quite agree with Dick in thinking I ought to be doing better for myself."

"It's hard to bring up children, and then see them go off to foreign parts so easily," murmured the poor mother.

"Why, mother, you've got Susan, and Tom, and Bess all settled near, and I'll come over and pay you a visit when I've made my fortune; and you may be sure I'll never forget the dear old folks at home;" and John laid his hand affectionately upon his mother's shoulder.

"I say, can't you stop your sentimental rubbish, and get to business?" cried Dick.

The mother sighed, and knowing well what Dick would consider a necessary prelude and accompaniment to business arrangements, brought out a bottle of spirits, some hot water, and glasses.

"Come, my dear, I'll just mix you a glass, and we'll make up our quarrel and be friends," said Dick graciously to Ruth.

"Pray don't trouble, for I never take anything of the kind," replied Ruth, very stiffly.

"Mean to say that you belong to the teetotal set!"

"I do."

"Well, I'm glad Jack's got better sense than to follow your example," answered Dick; and from that time he treated Ruth with open disdain.

For John's sake she controlled herself, and sat beside[20] him listening, with an aching heart, to the account of colonial life as Dick had known it; watching also, with a vague uneasiness and dread, John's frequent applications to the spirit with which his brother supplied him. If, in her presence, he so readily yielded to Dick's persuasion to take "just a drop more," what might be the consequence when he was far away from her, and completely under his brother's influence?

In one hour all Ruth's bright hopes for the future, and John's well-doing in a distant land, faded; and when she passed out of the reeking atmosphere of the little room into the cool, tranquil moonlight, her heart seemed to have died within her.

"I don't mind for myself, John; but, oh, I'm sure he won't do you any good. I wish you would go out by yourself, and not depend upon his promises, for I feel he isn't to be trusted."

"Rubbish, Ruth; who should I trust if not my own brother? and besides, I've got my eyes open, and am able to look out for myself."

"But, John, do forgive me for saying it, you didn't look out for yourself even this evening, for you let Dick give you more brandy than you have ever been in the habit of taking, and it has made you quite[22] unlike yourself, and I cannot help being afraid of what may happen if you go away with him."

"I suppose you mean to say I'm drunk," angrily cried John.

"No, John, I can't say that; but it wouldn't take much more brandy to make you so."

"Then you'd best go home by yourself, for I'm no fit company for you," and John roughly threw Ruth's hand off his arm, and turned back with unsteady footsteps towards the town. The girl stood dismayed. John was indeed quite unlike himself, to leave her in a lonely road to find her way home unattended. She waited for some time, hoping that he would relent, but the last sound of his footsteps died away, and presently she slowly walked on.

"Why, where's John?" asked cook, as Ruth entered the kitchen.

"Oh, he'll be in directly, I expect. He's just turned back for something. You go off to bed, and I'll see to the fire," carelessly returned Ruth.

"Something wrong, I believe," said cook to herself, as she lit her candle, and followed Jane upstairs.

For an hour Ruth waited, and then, unable to bear the suspense, she threw a shawl over her head, and slipped down to the garden gate to watch for John. At length, shivering with cold, she was about to return to the house, when she heard in the distance the noisy snatch of a song. "It can't be John, of course; but I'll just hide behind the laurels till the drunken fellow[23] has passed," thought Ruth. Nearer and nearer came the sound, till, with beating heart, Ruth stepped into the moonlight, and laid her hand on the lips that were profaning the stillness of the midnight air.

"Oh, John; hush, hush! If master should hear you! Oh, what have you been doing, my poor boy?" John made but a feeble resistance to the strong loving hands that drew him into the house.

"Well, I've had a spree, and why mayn't I, with my own brother?" he said, with an inane smile on his face, as he sank into a chair. Ruth made no answer, but wrung a towel out of cold water, and bound it around John's throbbing temples. Then she put the remains of some strong coffee, which had been sent down from the drawing-room, over the fire.

"Drink it," she said, offering it to him when it was sufficiently heated.

"It's horrid," said John, shuddering as he tasted the unmilked, sugarless liquid.

"It will do you good; drink it at once." John obeyed, and Ruth stood watching the effect of ministrations such as she had so often rendered in the past to her drinking mother. In a few minutes John rose to his feet with a sigh.

"I've been a fool to-night, Ruth; but I'll go off to bed, and by morning I'll be in my right senses," he said.

She lit his candle, and carried it for him to the foot of the attic stairs, then went to her own room,[24] and till morning light dawned, resolved endless schemes for preventing the carrying out of John's plans to go abroad with the brother whose influence had already been so powerful for evil. Finally, she determined to speak plainly to John, and tell him she could never consent to follow him if he had anything to do with Dick, unless he promised to sign the pledge before going away. Then she fell into a troubled sleep, until it was time to commence another day's duties.

"I'm desperately ashamed of myself," said John, when alone with Ruth the next day; "can you find it in your heart to forgive me for costing you so much pain?"

"Don't talk of forgiveness, John; I shall think nothing of all I have suffered, if it will only teach you to be careful and avoid drinking with Dick in the future."

"I promise you he shall never make me forget myself again; and if you will only trust me, dear, I'll try and hold my head up once more."

"I do trust you, John; but I want you to do what I have done, and promise faithfully not to touch drink again. If you take only a little, it may lead to more, as it did last night; but if you can say 'I never touch it,' you put yourself out of the way of being tempted. Do listen to me now, and be persuaded."

"Really, Ruth, that is too much to expect. It isn't manly to be bound by a pledge, and it makes a fellow[25] look as if he hadn't any pluck or self-confidence to be afraid of a glass. Why, I believe Dick would have nothing to do with me if I took your advice."

"So much the better, then," was the decided answer; "Dick will be your ruin if you depend on him. Do give him up and go out by yourself. Master would give you testimonials to his friends in Melbourne, and you could be quite independent of your brother."

"I'm not going to depend on Dick; I've got myself to look to. All I want from Dick is a start, and I'll take care he doesn't lead me into harm's way. If not for my own sake, for yours, Ruthie, dear, I will be careful."

It was hard for Ruth to utter her determination after John's tender words; but the bitter past had been too vividly before her all the morning to allow her to falter in her purpose for more than a passing moment.

"John," she said, "I've quite made up my mind that I cannot follow you to Australia unless you take the pledge first, or at least promise that you will not take intoxicants; for, unless you do so, I know that with the many temptations you will meet, especially if you persist in going with Dick, that all hope of a happy home will be at an end, and I will never risk passing through what I once did."

"What on earth are you saying, Ruth? Why, you've promised and can't break your word. I'm[26] going for your sake, and here you say you won't come out to me," cried John, scarce believing his ears.

"No, John, I can't, unless you promise what I wish. When I passed my word to you I didn't know what I know now, and I'm quite justified in recalling my promise."

"You're a cruel, hard-hearted girl, and I don't believe you care a straw for me, or you wouldn't make a hindrance out of such a paltry thing. I only made a slip yesterday evening, and I vow it shall be for the last time."

Deeply pained, Ruth only shook her head.

"So you won't believe me! Well, I'll promise no such thing as you ask. I won't be tied to any woman's apron strings," and in extreme irritation, John flung himself out of the kitchen.

"This is too hard!" exclaimed Ruth despairingly. Poor girl! the only earthly brightness that had ever come to her was soon quenched in gloom, and she knew nothing of the comfort and peace which faith in the protection and love of a Heavenly Father can afford in the darkest hour. No wonder that courage and hope nearly died out of her stricken heart. The days went by, and John made no attempt to bridge the chasm between himself and Ruth. She knew he was making preparations for speedily leaving England. She also knew that whenever he returned from visiting his father's home, he was more or less the worse for drink. As usual, she stayed up for him,[27] and kept her knowledge of his condition from her fellow-servants, though she could not hide from them that the relationship between them had changed.

"You're not treating that girl well, I believe," said cook sharply to John one day; "you'll never meet her equal again, though you may cross the seas."

"Mind your own business," angrily retorted John, following Ruth into the garden.

"Have you anything to say to me, Ruth? I'm going home to-morrow, and I expect to sail next week," he said. If his tone had been less hard, Ruth might have ventured to plead again with him, but she simply said:

"No, John, I have said all that I mean to, except that I wish you all success and happiness."

"Same to you, Ruth," dryly responded John, and turned on his heel.

"She is greatly changed, poor girl, and though I cannot get her to confess it, cook tells me there was some misunderstanding between her and John, and that she has not heard from him since he sailed," replied his wife.

"She told me the other day he had arrived safely and was doing well in a store," said Harry.

"She would hear all that from his parents; but, my dear, you had better try and win the girl's confidence, and see if you can do anything. It's a thousand pities for a young thing to mope and pine away her best years, when a little advice may set matters right, and make two people happy."[29]

"I'll do what I can, but I'm afraid it will not be of much use," said Mrs. Groombridge.

"Ruth," she said, when retiring that evening, "I want you to do one or two little things in my room."

"Yes, ma'am," replied Ruth, and followed her mistress upstairs. As she was flitting about the bedroom Mrs. Groombridge suddenly asked:

"By the bye, Ruth, when did you last hear from John?" Ruth turned away to hide the painful flushing of her face.

"I—I—what did you say, ma'am?"

"When did John last write to you?"

A silence ensued, and then Ruth said: "He's written to his parents, ma'am, and not to me."

"Why, how is that, Ruth? Surely you expected to hear from him."

"Not much, ma'am," Ruth forced herself to say.

"But, Ruth, if you are going out to marry him, he ought to write to you, and you ought to expect him to do so." Ruth's apparent apathy gave way as the remembrance of all her happy dreaming swept over her at her mistress's words. She buried her face in her hands and wept bitterly. Mrs. Groombridge laid a kindly hand upon her shoulder. "Sit down, my poor child, and tell me all about your trouble. Something is wrong between you and John, and perhaps I can help to make it right."

"Oh, no, no, ma'am, it's past any one's help," sobbed[30] Ruth, and by degrees her sorrowful story was told. "And, ma'am, I know that his brother will be the ruin of John; he'll go downhill fast, as many a fine young fellow has done."

Mrs. Groombridge looked grave. She was no abstainer, as we know; but she could not help seeing the danger that menaced John, if he could be so easily persuaded to overstep the limits of prudence and sobriety.

"Yes, Ruth, I think there is cause for anxiety about John, but you must not lose heart. I think you acted unwisely in letting him go as you did; at least you might have gone out to him if you knew he was keeping sober and doing well, and the very anticipation of your coming might have given him a motive and impetus that nothing else could. Men dislike to be forced into anything, and have a great objection to be bound by a pledge. You should have been more careful in urging that."

"But, ma'am, John was one of those who needed to promise, for he's good-tempered and obliging, and doesn't know how to refuse a friend."

"Still, I think you were too hasty in cutting away the hope he had of your going out to him. What has he to look forward to?"

"Perhaps you are right, ma'am. I might have waited; but I was frightened to think of what might lie before me. I know the misery of a home cursed by drink."[31]

"Ruth, will you write and say as much to John? Tell him you'll come out to him as soon as he has a home ready for you, and he can assure you that he is leading a sober life."

A hard, almost defiant look passed into Ruth's eyes for a moment. She thought how cruelly John had left her, without a word of tenderness, and she said coldly: "Oh, no, ma'am, I couldn't do that; if John would write and ask me, I might; but I will never humble myself to him, for he has been wrong and unkind all through, and I dare say he's glad to be free." She had said the same to herself many a time since the morning when John had said good-bye to her with as much composure as if he were going to return in a few hours, and she had almost grown to believe they must be true. Nevertheless, her heart leaped to hear her mistress say:

"You should not try to think that, Ruth, for I believe you wrong John by doing so; he is true and manly, and probably he would be only too happy to receive a letter from you."

"Well, ma'am, I don't feel as if I could write first," was the obstinate reply; and Ruth presently left the room with a still heavier heart than she had entered it.

"It's a sad case, George, and my conscience is not at rest about the part we have played in it," was Mrs. Groombridge's remark to her husband, after retailing her conversation with Ruth.[32]

"How are we to blame, my dear?" was the surprised question.

"I can't help remembering how we laughed at Ruth for her fanatical whims as we called them, and encouraged John to do the same. Events have proved she was right. Perhaps if we had taken another stand, John might have followed Ruth's example, and all this unhappiness been spared to both."

"Perhaps," was the curt response.

"Harry, my boy," said his father the following morning, "how many cases did I hear you say you had at the hospital the other day which were the result of drink?"

"About three-fourths, father; of course, not all caused by the drinking habits of the patients themselves: but when a child is brought in badly burned because its mother was off on a drinking spree, or when a man has been run over because a driver is the worse for drink, or even when a woman is dying of disease, the result of want and neglect which drink has brought about, I suppose it's quite fair to credit the drink as the indirect cause of such cases."

"Oh, decidedly! Good gracious! I wish the Government would let all other questions go to the wall, Ireland included, while they did something to mend matters!"

"My dear, how would you like Government to step in and stop your supplies?"[33]

"I'd be content they should do that, if it were for the public good," warmly replied Mr. Groombridge.

"I have heard of private individuals not waiting for the interference of Government; but who, believing it to be for the public good, have themselves banished all intoxicants from their homes," said Mrs. Groombridge, in a meaning tone.

Mr. Groombridge looked thoughtfully at his wife across the table, but said nothing, and the subject dropped.

That evening Jane the housemaid bounced into the kitchen, and flung herself into the nearest chair.

"What's the matter now?" asked cook, glancing at her disturbed face.

"A very good matter indeed! I'm going to make a change. I've had enough scolding and faultfinding, as I told mistress a minute ago."

"I suppose she's given you a month's notice, and you deserve it richly for your saucy tongue."

"You're a fine one to talk, for I couldn't hold a candle to you! Yes, she told me I had better look out for another place, and I told her it was just what I had thought of doing."

"Well, I hope you'll be taught a lesson, for I tell you there aren't many mistresses as kind and considerate as Mrs. Groombridge, and you'll find it out to your cost, I'm afraid," said Ruth.

"You've got no cause to complain, for every one of them pets you up to the skies," replied Jane.[34]

"Ruth's earned all she gets, and so have you, Jane, for the matter of that. She's obliging and respectful, and you're disagreeable and pert half your time," said cook.

"I ought to be flattered, I'm sure," retorted Jane, tossing her head as she sat down to continue her work of trimming a hat with some particularly smart ribbons and flowers. The month passed and Jane left, a new housemaid coming in the same day.

"A different sort to Jane, I can see," whispered cook to Ruth, as the new-comer went upstairs to take her bonnet off. It was a pretty, modest face that presently showed itself in the kitchen; but there were traces of sadness about the eyes and mouth, and the new housemaid's dress was trimmed with crape.

"Poor thing! perhaps she's lost her mother," thought Ruth, and cook's usually sharp voice softened as she asked the girl her name.

"Alice Martin," was the timid reply.

Ruth looked up with a wondering glance at Alice, who entered the kitchen at that moment with brushes and brooms. A Bible-reading, praying housemaid was a curiosity she had never witnessed. But Alice looked bright and business-like enough to allay any fears respecting her capability to perform her allotted tasks, and after a pleasant "good morning," she proceeded to go about her work in a manner that showed she knew all about it. After a few weeks had passed, both cook and Ruth agreed that the new girl was quite a treasure, with the reservation from cook, who saw no connection between Alice's religion[36] and her daily life—"if it wasn't for her precious chapel-going and religious humbug."

"Come with me for a walk, Alice, instead of going to your class; it's a shame to stay indoors such an afternoon," said Ruth, one Sunday.

"Oh, I couldn't miss my class for anything; but do you come with me, and we can have a little walk after."

Ruth hesitated. She knew that cook would laugh at her for going, but she was feeling low and depressed, and the thought of a solitary walk was irksome to her.

"Well, I don't mind, just for once. It's miserable to walk by one's self," she said.

So she went to the Bible-class which Alice so regularly attended. The lesson was interesting and impressive, and as, from the lips of the minister's wife who gave it, there fell words of invitation to the sin-burdened and weary, Ruth felt strangely moved. Unconsciously her tears fell, for her heart ached with loneliness and longing as she heard of the Saviour and Friend, who was willing to come into her life and crown it with His forgiving love and mercy. She walked on in silence by the side of her companion.

"How did you like Mrs. Evans?" Alice presently asked.

"She made me feel wretched; I don't want to go again."

"That was just how I felt when I first heard her[37] talk; but do go again, for she will do you so much good."

"You never had such reason as I have to be wretched and miserable," exclaimed Ruth.

"Oh, you don't know; I've had more trouble than I've known how to bear; and then there was the burden of my sins that made me more unhappy than I can tell you," added Alice, timidly.

"I don't know anything about that; but I do know that my life is a burden. I had a wretched home, and when I went to service, and something that seemed too good to be true came, it was just taken from me, and now, I'd like to die and be out of my misery."

"Do tell me what your trouble is, dear, then I will try to help you," affectionately pleaded Alice.

Ruth needed no persuasion. The sweet consistency of Alice's life, her invariable good temper and readiness to help, and a certain wistful look in her eyes when Ruth was more than usually depressed, had won her confidence and affection, and the story of her life was readily poured into the ear of her sympathising fellow-servant.

"And now," concluded Ruth, "if you think there's any hope or help for me, I shall be surprised."

"Ruth, I know what it is to have a home like you have had, and I know what it is to lose one more dear than any, and I can not only sympathise, but I[38] can assure you there is both hope and help for you," replied Alice, with full eyes.

"Poor girl! then you have suffered, too!"

"Yes, my father drank himself to death, and my mother died of a broken heart soon after, and then I went to service. I was engaged to a young man I had known a long while, and we were to have been married this spring, but he died quite suddenly, and I thought my heart would break; but Mrs. Evans came to see me, and helped me so much. She told me of the One who can heal every wound, and now, if I feel lonely and sad sometimes, I know I have a friend in Jesus, and I just go to Him and tell Him about my heart-ache, and He comforts me."

"Would He give me back my John, if I asked Him, do you think, Alice?" suddenly asked Ruth.

"Perhaps He would, but He will certainly help you to bear your sorrow if you go to Him."

"I'm afraid to go to Him, Alice. I'm only a servant, and I've done a great many wrong things, and He might be angry."

"No, dear, for He says: 'Come unto Me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden,' and He means it. Take your sins to Him first, and ask His forgiveness, and then tell Him all about your trouble. Shall we hurry home and pray together?"

"Oh, yes, for it's all new to me, and I would like you to show me how to pray."

The two girls hurried home, and knelt together,[39] while in simple, heartfelt words, Alice laid the need of her companion at the feet of Him who hears and answers prayer.

"That has done me good; thank you so much, Alice," whispered Ruth, with a grateful kiss.

"You will pray by yourself, won't you, dear?" asked Alice.

"Yes, and for John too," answered Ruth, a bright hope already dawning in her heart.

That evening, at Alice's suggestion, she looked through the Bible for promises to meet her special need. When she went downstairs to lay supper, it was with a glad heart at the abundant encouragement she had received. From that time she commenced a new life, and though her feet often faltered in the upward path, and her heart sometimes grew heavy with foreboding fears, a light had arisen for her which grew brighter as the months passed. Many times she sorely regretted that she had let John go from her in pride and anger. If she had but the opportunity now—and her heart ached for it—how tenderly she would plead with him to be true to himself and her.

"John says he supposes you've forgotten all about him," said Mrs. Greenwood one evening, when she had called.

Ruth's face grew scarlet.

"Why doesn't he write to me, then, and let me know what he means?" she cried with bitterness.[40]

"I'm sorry you should have quarrelled, my dear, for I believe you're the very woman for him; and I know he's desperately fond of you, and here's Dick saying Jack would do better with a woman to keep him out of mischief."

"What's his address?" asked Ruth. It was written down for her, and she soon made an excuse to leave. There were many conflicting thoughts and emotions at work in her mind and heart. How could John suppose she could ever forget him? Had he said anything to his mother about his being desperately fond of her, or was it only Mrs. Greenwood's surmisings? And what did Dick mean by saying that John would do better with a woman to keep him out of mischief? Was he going downhill so rapidly that his degraded elder brother had lost control over him? Might John himself be longing for an assurance that he was forgiven, and if the assurance were given, would it be a help and stay to him? Oh, if she dare think so! Well, she would risk it, and write that very night, and as she made the decision a great burden fell from her, and she knew her decision was right.

Far on into the night Ruth sat writing sheet after sheet by the light of her candle. She wrote of the new joy that had come to her since John left, and told him it had only increased her love and yearning for him; how night and day she prayed that he might be kept from harm and evil, and that[41] some day they might yet meet and be happy. She concluded by asking him to forgive her, if she had seemed hard and unkind, and reminded him again of her own painful past, and how she felt it was wrong to face a future that might hold a like experience for her; but if he could only assure her that he was living a sober, respectable life, and intended doing so, she would come out to him just as soon as he had a home ready. Then with many tears and prayers Ruth directed her letter and went to bed.

Ah, poor Ruth! could she have foretold the fate of her letter, how would the bright hopes she was entertaining have been quenched in darkness!

"Why, yes, I believe there's a packet knocking about. Jones, reach 'em off that shelf," answered the foreman.

A letter from his mother, and another in a strange handwriting to John, was passed across to Dick, who took them and left the store.

"That plaguey boy may fetch his own letters. Blowed if I'll waste my time calling round; but who's been writing to him now, I wonder? Some woman's hand. That means mischief, for sure!"

Dick turned the envelope over, and studied the calligraphy with an air of uncertainty. Suddenly he exclaimed, half aloud:

"It's from that soft fool of a girl, I'll bet anything. She's found out which way her bread was buttered, and means to come the doubles over Jack; but not[43] quite so easy done, my girl. The boy's got a brother who'll look after him, so here goes;" and Dick tore open the envelope, glanced at the signature, nodded his head in triumph, and deliberately read the closely-written pages.

"The lying humbug! So that's the way she'd throw dust into Jack's eyes, and he'd be as innocent as a new-born babe, and write back begging her forgiveness, and telling her he'd be ready for her in a trice! Bah, how I hate such tomfoolery!" and Dick tore the letter, which had been written with so many tears and prayers, into a hundred fragments, and sent them flying down the street.

Some days later found him back in a bush settlement, where he had, a few months before, persuaded John to join him. Despite the latter's attempt at bravado, he had left England with a very sore heart, and a resolve to show Ruth that he could keep steady, and make his way in the new land. He quite intended to save money towards preparing a home; and thought that, in a year or two, he would write to Ruth, and ask her to overlook the past, and come out to him, for he never doubted her love and fidelity. But, though he had soon found a situation where he might have risen and achieved his purpose, he had no sooner commenced to save than his brother Dick would appear, and lead him into scenes of revelry and dissipation, where his money would be more than wasted. After one of these times John said, with bitterness:[44]

"Pity I didn't bring my Ruth out! She'd have kept me straight instead of helping me down as you do."

In a letter that Dick had subsequently written home, he had sneeringly said that Jack wanted a woman to look after him. What effect that remark had upon Ruth we have previously seen.

Finally, Dick had persuaded John to leave his situation, and join him and his lawless companions in their wild bush life; yet, even there, his thoughts often reverted to Ruth, and he made up his mind that if she would only break the silence and tell him she cared as much as ever for him, he would leave his present surroundings and begin a new life. Often, when engaged in pursuits new and exciting, or carousing with companions as degraded as his own brother, the sweet, happy restraints of the old home life, and the pure face of the woman he loved would rise before him in vivid contrast, and with an unutterable loathing he would turn from his present life, and long to be free. Yet he lacked moral courage to break from his brother's influence; and, as John, in many ways, proved serviceable to Dick, the latter, by flattery or by threats, was continually strengthening his hold upon John's weaker nature. So Dick was rejoiced that Ruth's letter had fallen into his hands, well knowing that John could never have withstood the temptation it would have presented to him.

"Any letters from home, Dick?" inquired John[45] of his brother, who sat before a rough, uncovered table, making heavy inroads upon the provisions with which it was loaded.

"There's one in my coat," answered Dick, nodding in the direction of his top-coat, which he had flung aside on entering. John got up and felt in the pocket, and drew out his mother's letter.

"No other, Dick?"

"No; ain't that enough for you?" was the answer.

John took the letter and went out of the room.

"She is too hard on a fellow, she is; but, oh, Ruthie, if I had you here, I'd be out of this soon enough!" he said to himself.

Yet, all through the hours of the following night, John laughed as loudly and drank as deeply as any of the rough men who had been invited to meet Dick, and listen to the news after his short absence from the settlement. In the early dawn, the company broke up, and left the log building, making, as they went to their several homes, the still, fragrant air resonant with snatches of ribald song and coarse jest.

Dick threw himself upon a settle and was soon sleeping heavily; but John staggered out of the noisome atmosphere, and leaned against the framework of the door. The cool morning breeze fanned his heated brow, and the twitter of the birds fell on his dulled ears. The stars had paled, but the moon shone clear in the blue sky, now fast taking on the gorgeous hues of the dawn. He stood, unconscious[46] of the beauty of scene and sound around him, till the echoes of his late companions' unhallowed mirth had died away. Then there came to him, as there always did at such times, the thought of Ruth. What would she say to see him now? Yet, deeply though he had fallen, John would have given worlds, if he had possessed them, to have stood in her presence at that moment with drooping head, and confessed all his weakness and misery, and begged her to forgive him, and help him to retrieve the bitter past.

"Oh, Ruth, you took the pledge for my sake, and now, if you were only here, I'd take it for my own sake and yours too," groaned John.

It was only the fancy of a heated imagination, of course, but just then, as the first ray of the rising sun glanced through the forest clearing, and fell at his feet, he felt himself looking down into Ruth's upturned, pleading eyes; her hand lay on his arm, and her voice said: "For my sake, John, take it now!" He started, as if from a dream, and looked round. No apparition melted into morning mist, no human form was yet stirring, but, with a strange, mingled sense of awe and gladness, John said:

"Bless you, my Ruthie, I will, for your sake! You shall never have cause to be ashamed of me again!"

Then he turned indoors, and, throwing himself down beside his brother, was soon fast asleep.

"I quite believe that, Dick, for you've done your best to bring me to it," replied John.

But Dick poured out such a volley of oaths, that John wisely forbore to say anything further.

Finding he could not provoke John to retaliate, Dick sneered: "I suppose now you've sown your wild oats, and got all you could out of me, you'll be sending for that smooth-tongued, virtuous wench to come out and help you keep straight, for such a poor weak fool as you'll never do without some one to look after you; but see if I don't let her know a few of your nice little secrets."[48]

John's blood was raised to boiling-point. He started to his feet, and the next minute Dick lay prostrate before him.

"Take that," he cried; "and if you dare to say one more word about her, I'll give you cause to repent it. You're not worthy to lick the ground she treads on."

Dick looked up, but neither moved nor spoke, while his younger brother thrust a few odds and ends into a bag, and prepared to leave. Coward as he was, he feared to provoke John's just anger again, and not till after the door was violently slammed behind his brother, and the sound of his rapid footsteps had died away, did Dick rise from the ground.

Then he shook himself to ascertain if he had received any damages, and finding himself not much the worse for his fall, he sat down and took out his pipe. For some time he smoked furiously, and then struck his hands together as he exclaimed:

"I'll do it, as sure as I live! I'll pay him out for this, or my name's not Dick Greenwood."

Three days after, John walked into the store in Melbourne, where he had been previously employed.

"It's you, is it?" said the foreman; "ain't you satisfied with your change?"

"No," said John, with emphasis; "I'd rather sweep a crossing. I suppose you've filled my place."

The foreman nodded, and jerked his thumb in the direction of a young man who was leisurely serving a customer.[49]

"Do you really want work, man, or is it only 'come and go' again?" asked he, seeing that John looked disappointed.

"Mr. Smith, I'd give anything for a chance to work. I'm sick of knocking about."

"Well, look here! he ain't up to much good," and the shopman was again indicated; "got no 'go' in him, and you always suited me. You may come and show him how to do business in my line, but you'll have to start with lower wages, eh?"

John thankfully accepted the offer. "Now for Ruth and a home of my own!" he said the next morning, when beginning his work.

It was scarcely a wise decision he had made, not to write to her until he was ready to send for her; but a certain feeling of pride held him back, for he said: "She doubted me once, and now I'll wait till I can prove myself worthy of her trust."

Meanwhile, in heart-sickening suspense, Ruth waited mail after mail for an answer to her letter. At last there came one for her, bearing the Australian postmark. She tore it open in fear, for the handwriting was strange. It ran as follows:

"Dear Miss,

"I am sorry to send you bad news, but you must take it kindly from one who wishes you well. The truth is, that Jack is going to the bad as fast as he can, which I'm sorry to say of my own brother. I was downright ashamed of the way he went on, after reading a letter[50] you sent him. He got real mad over it, and swore he'd have nothing to do with a canting Methodist, and a deal more which I won't write, not wishing to put you about. Last of all, he tore the letter up. I write these few lines to save you from expecting to hear any more of him, as he's off on his own hook, and I wash my hands of the scamp.

"Hoping you are in health, I remain,

Ruth sat stunned. The bell rang, but she heeded not. Alice came up, but she took no notice of her anxious inquiries. Hearing of her condition, Harry Groombridge left the dinner-table and went to her.

"She's had some shock; this letter doubtless! May I read it, Ruth?" he asked.

The girl mutely assented.

The young man glanced through the contents, and handed it to his mother, who had followed him. She read it, and they exchanged looks. Then Mrs. Groombridge took one of Ruth's cold hands in hers, and said:

"Ruth, my dear girl, this letter is a hoax, I am persuaded, for you know John's brother is an unprincipled man. I think he has quarrelled with John, and then revenged himself by writing to you in this cruel way. I can't think John has gone so far wrong as to talk of you before his brother in such a manner. My impression is, that he was glad to get your letter, and left his brother, resolving to prove himself worthy of you yet."[51]

"That's about it," remarked Harry.

Ruth gasped with a sense of relief.

"Oh, if I could but think so; but then, why doesn't he write himself?" she said.

"I can't say, but trust him a little longer, Ruth. When did his parents last hear from him?"

"I don't know, ma'am. Lately I've felt I couldn't go there."

"You shall run down to-night; or stay, you are not fit to go. Harry, will you go at once to Mrs. Greenwood, and ask her to bring John's last letters?"

"With pleasure, mother." He soon returned with Mrs. Greenwood.

"You've had a letter from Dick, my dear, that's upset you, so the young gentleman says. I hope he's all right, for it's long since we had a line, though we hear every other mail from John," she said.

"Do tell me where he is, and what he is doing, for Dick says he is going to the bad fast, and I can't believe it," said Ruth.

"That I'm sure he isn't," cried the mother; "he left the store to go with Dick, but he's gone back now, for he says it was a wild life that didn't suit him, and he got into a bad set; but he's doing well now, and living quiet and respectable, and tells us he has signed the pledge, and—and—but oh, my dear, I wasn't to tell you this; for he meant to write himself and tell you all about it, but you were so anxious, what could I do?"[52]

Ruth's eyes filled with happy tears. How abundantly her prayers were being answered she only found when she came to read John's letters!

"I must wait patiently till he writes to me; but why doesn't he reply to my letter?"

"Depend upon it, Ruth, he never had it, or he would at least have mentioned it when writing home. It must have fallen into his brother's hands," replied Mrs. Groombridge.

"I don't believe Dick is as bad as that," said the mother, when Ruth's mistress had left the room.

"My dear," said Mr. Groombridge, after hearing the story; "I shall persuade Ruth to go out at once. Our friends, the Grahams, who find it so difficult to secure good servants in Melbourne, will be only too glad of Ruth's help until John can make her a home, and she will be a strength and stay to him, and all suspense for her will be over."

"I don't like to part with Ruth a day before I'm obliged, but I think your plan excellent," returned his wife.

It was discovered that, when consulted, Ruth's opinion coincided exactly with that of her mistress, and a month afterwards she bade farewell to her friends and sailed for Australia.

"You've a young man named Greenwood in your employ, I believe?" said a gentleman, walking into the store where John was engaged.[53]

"Yes, I have, sir."

"Can you spare him an hour or two? I want him to meet a friend who is coming in by the steamer to-day from England."

"Certainly, sir. Here, John, this gentleman wants you to go down with him to the Docks."

John looked surprised, but, supposing it to be a business call, put on his coat and hat and walked out.

"Are you expecting a friend from England?" asked the stranger.

"No, sir, I wish I was," was John's involuntary reply.

"I had a letter from my old friend Mr. Groombridge, of Bristol, and he asked me to call for you on my way to the Docks, as some one you once knew was coming in by the steamer."

"Who did he say it was, sir?" asked John, with a sudden tumultuous beating of the heart.

"He did mention the name, I believe; but, dear me, I've left the letter at home. It's no matter, though, you will soon learn," said Mr. Graham, with an amused smile, as he watched John's face.

"It couldn't be, of course," argued John to himself; but as the steamer came in he eagerly scanned the faces of the passengers, with but one thought.

No, she was not there, and with a bitter feeling of disappointment he fell back.

"John! Oh, John!"[54]

He looked up. How could he have overlooked that figure with eager hands stretched out towards him! Yes, it was his trusting, loving Ruth, who, unasked, had crossed the seas to help and cheer him in the hard battle he was fighting for her sake.

"Oh, Ruthie," he said, as he grasped her hands; "I don't deserve this. Why have you come, darling?"

"Why, I came for your sake, of course, John; but are you quite sure you want me?"

"You may well ask that, for I've been a brute to you; and now I know I ought to have written to you, but you might have sent me a line, Ruth."

"So I did, and I believe Dick must have got it."

"The scamp!" exclaimed John.

"Ah, don't say anything unkind now, for it's all happened for the best."

Then Mr. Graham came up, and John went to see about Ruth's luggage, further explanations and news from home being reserved till the evening, when John had finished his day's work.

When Ruth's long story was finished, John sat thoughtful and silent for some time.

"Yes, Ruthie, I do feel you are right. I want a stronger power than even my love for you to keep me from yielding to temptation, and I will from this time give my whole life, with its many sins and mistakes, into the Hand of the One who will forgive all, and make me a new creature," he presently said.[55]

"Thank God for that; we can help each other now, John!"

It was only a humble home to which John took Ruth a few months later; but mutual love and trust made it the happiest place on earth to the two who had waited so long for the fulfilment of their hopes.

"Guess what news I've got, John," said Ruth, with a beaming face one morning, shortly after she had been installed as mistress.

"You've drawn your money out of the Savings Bank, and taken passage in the steamer that leaves for England to-day."

"Foolish boy! No, I've had a letter from Alice, and she says that master and mistress have agreed to give up all intoxicants, and they say it's all through our example. How delighted I am, to be sure, aren't you, John?"

"Yes, little woman, I'm very pleased; but don't say our example, for you set the example, and you ought to have all the credit."

"Ah, John, you know I did it all for your sake, dear," whispered the happy wife.

"I'm sure I can't guess, George," answered the woman, with a pleasant smile on her face as she welcomed her husband.

"Well, don't drop the baby when I tell you. Tim Morris has signed the pledge!"

"Good gracious, George, you don't say so! Why, do you know, his poor wife came in yesterday morning to borrow sixpence, for they hadn't a loaf of bread or a bit of coal in the house; and Tim was out then, drinking like a beast. Really I can't help saying such things, George."

"Well this is what I'm told, Susan. He was picked out of the gutter yesterday evening by some teetotal folks, and taken to one of their meetings; and, drunk as he was, he signed, and then they saw him home, and early this morning they were round to see how he was; and anyhow he declares he is going to stick to it. They've taken him on at the works, and given him another chance of redeeming his character."

"I'm very glad to hear it, George; and if the teetotal folks keep Tim Morris out of the gutter, I'll never say another word against them, and shan't let you either."

"I don't think I shall want to if they do; but I've very little hope, Susan. It'll be the first time that ever I heard of a man who had sunk so low being reclaimed."

"Yes; all I've ever given that kind of people credit for doing, is to get as many little ones into their meetings—Bands of Hope, don't they call them?—and make them sign the pledge, and as soon as ever they get to a sensible age, they find out how foolish they've been, and break all their fine promises. And no wonder, for I don't know how people could get on without their glass of ale or porter two or three times a day. I couldn't for one."

"And I'm sure I should be lost without my pint at dinner and supper," echoed George, adding: "I guess we're the moderate drinkers teetotalers rave about."

"Stuff and nonsense," answered Susan. "Why[58] can't they abuse the creatures who never know when they've had enough for their own good, without wanting to take one of our necessary comforts from us, when we pay our way, and are decent, respectable people?"

"That's just what I say, wife. Such folks have neither sense nor reason on their side. But I can forgive them all their mistakes if they only turn Tim Morris into a sober man."

"Well, sit down, George, and hold the baby, while I put the tea into the pot. Go to father, mother's little pet;" and Susan Dixon placed the well-cared-for baby on her father's knee, where, amidst delighted screams and plunges, she speedily found congenial employment in burying her fat dimpled hands in his masses of brown hair.

"There, there, Mattie, won't that do for you, little lass?" said he, as he gave her back to her mother, crying with disappointment at the sudden termination of her delightful frolic.

"She does get on well, mother," he added, looking with fatherly pride on her rounded limbs and rosy cheeks.

"There's no earthly reason why she shouldn't, with all the care that's taken of her. Oh dear! it makes my heart ache when poor Mrs. Morris steps in here sometimes, with her sickly-looking child fretting in her arms, and our Mattie looking so different; I'd rather bury her, George, than see her like that."[59]

"I tell you, Susan, I think that a man who ruins the health and prospects of his wife and children ought to be treated as a felon, and sent to prison until he'd learnt to behave himself as he ought;" said George.

The conversation turned shortly after upon other matters, and presently, baby being put to bed, the husband and wife settled down to their usual pleasant evening; for never since his marriage, two years before, had George left his wife, after returning from his daily labour, for a longer space of time than was necessary to fetch the ale for supper from one of the neighbouring public-houses. They were perfectly happy in each other, and in the treasure which had been theirs for nine months, and wondered why every one could not rest contented as they did, in the pure delight of home joys.

Day after day, week after week, and even month after month passed away, and still, to George and Susan Dixon's unbounded astonishment, Timothy Morris kept his pledge, and into his wretched home there began to creep an air of comfort. Rags gave place to decent clothing, and the children no longer fled terrified at their father's approach.

"I've got another piece of news for you, Susan," said George one evening: "Timothy Morris is announced to speak at the Temperance Hall to-night."

"Well, I never did! What next?" exclaimed his astonished wife.[60]

"Well, I think the next is that, for the pure fun of the thing, I'll go and hear him, if you don't mind being left alone, my dear."

"Oh, no, not for once, George. Besides, I should like to know what Tim will have to say for himself; and you'll bring me word, won't you, dear?" replied Susan.

"Of course I'll do that; but I must be quick, for two of my mates are going to call and see if I'm coming. I can tell you it's made quite a sensation among the men to-day."

"I dare say it has," said Susan, bustling about, and hurrying her husband's tea.

That evening she waited, with the supper-cloth laid, for an hour past the usual time; and then, wondering what had kept her husband, took her post at the street door. Soon she caught sight of three men coming down the road, and at first thought she recognised George's figure in the moonlight; but hearing from the trio noisy snatches of song and loud laughing, she smiled at the absurdity of her mistake. But yet, as they came nearer, the tones sounded strangely familiar. Her heart sank as they halted before her, and her husband separated from them, and entered the house, pushing past his wife, and shouting: "Well, good night, mates; we've not signed the pledge, as our friend Tim advised, and don't intend to at present."

"George, where have you been all this time?" said Susan, as she followed him in.[61]

"In the right place for a Briton who never means to be a slave—to be a slave," he answered thickly.

"If this is what temperance meetings do for you, George, I think you'd better stay at home," said his wife in displeased tones.

"Don't be high and mighty, my dear; we weren't going to hear Tim Morris declare that the public-house wasn't a fit place for a respectable man to put his nose inside, without showing him that he'd made a confounded teetotaler's mistake; and being three respectable men, we went in, and took our supper beer there, instead of in our own homes. That's all right, isn't it?" he asked defiantly.

"If you had stopped at your own supper beer it might have been; but it looks more than likely that you drank your own and your wife's share too, judging from appearances," answered Susan bitterly, for she had been feeling the want of her usual stimulant for some time past.

"You can fetch yours, my dear; I've no objection, I'm sure."

"No objection!" Susan felt outraged. If he had been sober, such a word could not have fallen from his lips, for he never would permit her to enter the door of a public-house. There was no help for it now; she must go, for she could not do without her customary glass, and she dared not ask George to go, lest he should be tempted to imbibe still more freely than he had done.[62]

Putting on her bonnet, and seizing a jug, she hurried down the road to the corner where there were four public-houses blazing with light. She chose the quietest; and entering the jug and bottle department, found herself alone, and screened from all eyes, save those of the barmaid, who stepped forward to take her jug.

"Half a pint, please," said Susan.

Suddenly a thought struck her. If she took her ale home George would be sure to want some; and she knew that he had already exceeded by far his usual limit; why should she not stand and drink hers there? There was no one to see her; no one would ever be the wiser. It would only be just for once, she told herself, to put temptation out of her husband's way.

"If you'll kindly bring me a glass, I'll drink it here," she said to the barmaid.

"Certainly, ma'am;" and Susan rapidly drained her glass, and walked home with her empty jug.

If that night the heavy curtain which shrouded the unknown future could have been lifted, and to George and Susan Dixon there could have been revealed their unwritten history, with what shuddering awe would each have turned from the sin-darkened record, and cried with one of old: "Is thy servant a dog, that he should do this thing?"

[A] Reprinted, by permission, from "The Opposite House," published by T. Woolmer, 2 Castle Street, E.C.

"You needn't ask me, child. She's locked her door, and the little uns are inside; and here's the key. I 'spect she's off on a spree." The child took the key, and sighing heavily, proceeded on her way. Two of the children were screaming loudly, but ceased their cries as she entered the room, and began, one to crawl, and the other to toddle, towards the only being in their little world who never struck or kicked them, but tended them with the love and gentleness which, but for her, they would never have known.

"Mammie's left us all alone, Mattie; and Fan and baby has been crying all the morning, and Bob and me's been doing all we can, and they won't do nothing[64] but scream," exclaimed the eldest of the four children in wearied tones.

"That's right, Melie; you're good children; but I've come home, and 'll look after the lot of you. What's for dinner? Did mammie say?"

"There's some crusts left up on the mantel," answered Melie.

"Bob, you just climb up and fetch 'em down, and I'll nurse the baby, and, Fan, you come right away and sit by me." Mattie picked up the dirty, tear-stained baby, and seated herself on the only chair in the room. She had been to school all the morning, and, while ostensibly puzzling her little brain with the mysteries of "the three R's," her heart had been full of fear for those little ones in the house. What if her mother should leave them with the door unlocked, and Fan and baby should find their way headlong down those dark, steep stairs? Or, suppose the window in their room should by any means become unfastened, and one of them should fall to the pavement beneath; for Mattie remembered that, only the week before, a drunken mother had let her baby drop from her arms out of the window at the top of the house into the court below, from whence it had been picked up a shapeless, bleeding mass. So she was greatly relieved that everything had gone well in her absence. As for Fan's and baby's crying, that was to be expected while she was away.

"I shan't go to school this afternoon; 'taint to be[65] expected as I can, although teacher'll be just mad, being as it's near 'xamination time," declared Mattie.

"That's prime, Mattie! What'll we do? Not stay up here all the time?" cried Bob.

"In course not. We'll have our dinner, and then we'll just get a breath of air in the park. It'll do baby good; won't it, darling?" said Mattie, stooping over her puny charge as fondly as if he were the bonniest baby in the land, instead of a feeble, wan-faced infant, upon whom, as indeed upon each of the group which surrounded him, there was stamped the unmistakable imprint of an inherited curse.

"I'm glad mammie's out, Mattie. I wish you was our mammie, and could take us clean away," said Bob, hanging about Mattie's chair.

"When I get bigger and can earn money, that's what I'm going to do, you know, Bob. Me, and Melie, and you'll just work and keep the children, and we won't have 'em knocked about, poor little mites, will we?"

"No, we won't, but I wish we was big enough now," sighed Bob, to whom the tempting prospect was sufficiently familiar and delightful to help him to bear bravely the privation of his daily lot.

"Well, we ain't, so it's no use wishing we was," responded matter-of-fact Mattie; "but I'll tell you what I do wish, and that is as mammie and daddie'd just turn over a new leaf, and stop the drinking. Then we'd never need to be talking of running away[66] and leaving 'em; for I tell you, we'd all pretty soon know the difference."

"Tell us what a nice home we'd have afore long, and what jolly things we'd get to eat," said Bob.

"Don't you be so greedy, Bob. 'Tain't the want of good things to eat as troubles me so much. It's the rows, and the swearing, and the kicking, and beating, as takes the life out of one," and Mattie's face grew dark as she spoke.

"Mattie," asked Melie, as she munched away at her crust; "do all mammies get drunk like ourn?"

"They do about here, I b'lieve," answered Mattie, somewhat dubiously; "but lor, no, child, in course they don't. There's the lady in the shop where we buy our penn'orths of bread, as allers is as kind and pleasant spoken to her little uns as—as—"

A comparison was not speedily forthcoming, but Bob finished his sister's sentence by saying: "Like you are to all of us, Mattie."

"I'd hate to speak cross to bits of things like you," answered Mattie loftily, but with a little glow at her heart because of the spontaneous tribute to her sisterly care. "We'd better be off, I'm thinking," she said presently, and tying an old rag under the baby's chin by way of head-gear, she passed her own battered straw hat to Melie, saying:

"You can wear it this afternoon; I'll be quite hot enough carrying baby, without putting anything on, I guess."[67]