|

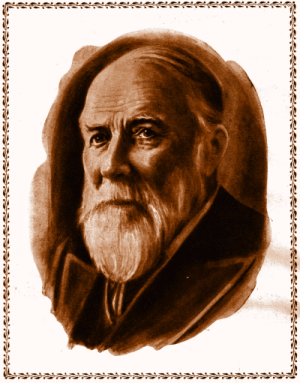

Written And Compiled By E.W. Cole (1832-1918) |

|

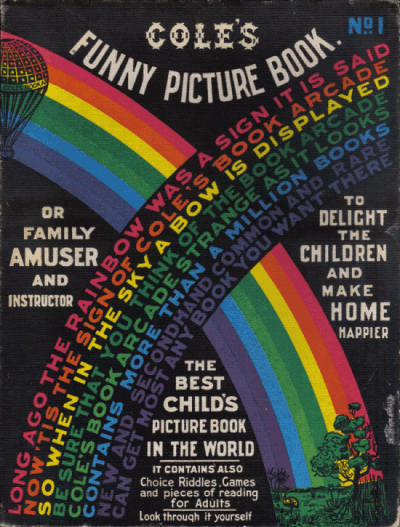

COLE'S Funny Picture Book No. 1

Or Family Amuser And Instructor;

It Contains Also Choice Riddles, Games

Long ago the Rainbow was a Sign it is said, |

|

[*] BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: The reprintings of this book since Cole's death in 1918 have involved very few changes, and in most cases it has been bibliographically misleading to term them "editions". Undoubtedly, somewhere in the past, the distinction between a "printing" and an "edition" has not been understood. However, with due cognisance of the irregularity, the practice of giving each reprint a new edition number accompanied by a running sales total is being maintained for statistical interest. |

|

Born Woodchurch, Kent, England

Died Essendon, Victoria, Australia

|

Page 1—Australia

|

I think that Australia, for it's size, is, all-round, the best country in the world. It's climate is pleasant and health-giving. It has no desolating blizzards, no frost bites, and few sunstrokes. In edible produce, for both size and quality, it stands very high, if not the highest. I have been in many lands, but never saw a country supply such a variety of products as Australia does—potatoes, onions, cabbages, carrots, peas, beans and scores of other vegetables in abundance. In fruits it produces apples, pears, plums, peaches, oranges, grapes, and Northern Australia also produces all the tropical fruits in abundance wherever cultivated. In corn Australia produces superior wheat, oats, barley, maize and all other kinds in abundance, especially when scientifically irrigated. As a milk, butter and meat country, it is one of the best in the world. It is the largest and best wool-producing country in the world. It contains the largest area in the world especially suitable for growing cotton, the most extensively-used clothing material. Flowers grow luxuriantly and beautifully whenever cultivated and watered. A few years ago when writing on the "White Australia" question, I stated that with high culture, water irrigation, and scientific irrigation, Australia was capable of supporting 400 millions of inhabitants. A high literary authority, in reviewing the book, remarked that this seemed like a "gross exaggeration"; but probably he had not thought so much on the subject as I had. I will here concisely state the principle reasons for my opinion. The great want of Australia, to make it amazingly fruitful, is the complete conservation of water and it's scientific application to the soil. Water, warmth, and soil will grow anything in Australia, if rationally managed. Australia has abundance of water now running to waste. On thousands of house-roofs water enough is caught for the domestic use of the respective families. Over large areas of the country there are 30 inches of rainfall, and the average rainfall over vast areas is 24 inches, and could be made much greater by cultivation. Four-fifths of this water now runs to waste. Again surface-parched Australia has vast areas of underground water which only require to be tapped and brought to the surface, to irrigate and fertilise the soil. Australia is also a country where timber grows well and fast, if planted in trenched ground and slightly irrigated. Hundreds of straight trees can be grown upon an acre of land if they are first planted thickly and some gradually thinned out. Many kinds of trees will grow upon very poor soil if they are properly planted and irrigated, as the bulk of their sustenance is derived from the air. One more remark about trees and their possibilities as food providers. Wherever any kind of tree will grow some kind of fruit tree will grow. There are hundreds of millions of gum trees growing in Australia. Where every one of these trees is, some kind of fruit tree would grow if properly planted and looked after. Again, to utilise Australia to it's full extent the whole world should be sought through for the best plants and trees of every kind, and only the very best grown, and those in situations and soil best adapted for them. One argument against Australia is that much of its surface is sandy, but experiments and developments in various countries show that the planting of marram grass, lupins, and other plants ties even the drifting sand together and gradually, through their decay, turns the sandy wastes into fertile soil. Besides, science can, in many other ways, utilise the elements in the air to enrich the soil.

|

|

It has been objected that in the above epitome no mention is made of the great mineral wealth of Australia. The reason is that minerals, exceedingly useful as they are in the arts, are not absolutely necessary (with the exception perhaps of iron) to the feeding, clothing, and housing of mankind. Vast multitudes have lived without them; but it may be remarked that Australia is a country very rich in minerals; some hold it the richest in the world. It possesses immense deposits of iron not yet utilised, and the most extensive gold-fields yet discovered. Australia and Tasmania have, according to the latest estimate of our Commonwealth Statistician, produced minerals to the value of £660,252,694—comprising in round numbers, Gold £474,000,000; Tin £24,000,000; and other kinds £8,000,000. The bulk of the above has been produced during the last 60 years, in a population rising from about 300,000 to 4,000,000 and it forecasts how vast the mineral-producing future of Australia is likely to be. Altogether Australia is a country as highly favoured by nature as any other of equal size upon earth, for the bountiful production of useful animals, vegetables, minerals, and men.

|

|

"'If we Australians took as much trouble to prepare for our summer as the Canadians take to forestall their winter, Australia would be THE MOST PROSPEROUS COUNTRY ON EARTH.' The speaker was the Rev. A. R. Edgar, head of the Central Mission, Melbourne. "'After circling the globe, then, you are still satisfied that Australia is not a bad country to live in?' "'The best,' said Mr Edgar, emphatically. 'I have no hesitation in saying that Canada and America are not to be compared with Australia. Unfortunately, England doesn't know it. Australia herself doesn't half realise it, and as for America and Canada, they haven't the remotest ghost of a notion of it. In England they learn with regrettable slowness, and their knowledge is scanty indeed; but across the Atlantic the ignorance is deplorable. "Australia?" says the Canadian. "Oh yes! Let's see, that's the place where it's always droughty—yes, yes, to be sure, the place where y' can't get a drink of water." He laughs at the idea of Australia producing as much wool and wheat as Canada, and bluntly tells you there's no country on the face of the planet can grow wheat and wool like his. But the fact is, there isn't a bit of territory fit to compare with the Western District of Victoria, for example, and conditions are infinitely harder for the agriculturist than in Australia. Canada's western district is icebound in winter, and her eastern lands are strewn over with great boulders, between which the plough works laboriously in and out'."—From the "New Idea." I often feel for the dweller in Canada; for notwithstanding his beautiful spring and autumn he has six months of ice and snow and freezing winds, and I feel selfishly grateful that my lot is cast in more genial Australia. Let us well ponder Mr. Edgar's concise and forcible statement: "If we Australians took as much trouble to prepare for our summer as the Canadians take to forestall their winter, Australia would be the most prosperous country on earth." This is quite true. The Canadian must thoughtfully and rationally prepare for his winter, or he would freeze and starve. We have no frigid climate to prepare against, but we have possible drought, and our first and greatest consideration should be the conservation of water for irrigation. This water conservation is exceedingly important thing. Men do not think, and the waste is enormous. When the rain falls it runs into the gully, from the gully to the creek, from the creek to the river, from the river into the sea; and then in the dry season water is deplorably scarce. I once asked a young squatter from the New South Wales side of the Murray "Have you got a garden?" He answered: "No: it is too dry up our way!" I said, "How do you get water for domestic purposes?" He answered, "We catch it off the roof; we catch it in 11 tanks and are never out of a supply." I asked, "How large an area have all your roofs put together?" He answered, "I think about 20 feet by 100 feet." This would be about a twentieth of an acre. Now just reflect! One acre of rainfall would supply, if caught, 20 establishments like that squatter's home, for the rain would fall fairly alike over that part of the country. A rainfall of 30 inches over an acre of ground measures about 680,000 gallons and weighs about 3000 tons, the bulk of which is allowed to run away every year! A gentleman said to me the other day, "Since the water was brought to Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie, under Sir John Forrest's great scheme, they have very beautiful gardens right along the line of supply. Wherever the water touches the land the vegetation is splendid, and, what is more, the evaporation is bringing heavier rainfall." Of course, wherever cultivation and irrigation are carried on, more evaporation takes place, and, in most cases, causes additional rainfall. When I affirmed that Australia was capable of supporting 400 millions of people I did not mean Australia as we now have it, but as it might be, and probably will be, when water is carefully conserved and its soil scientifically irrigated and cultivated.

E.W. Cole

|

Page 2—Cole's Funny Picture Book

Page 3—Index

|

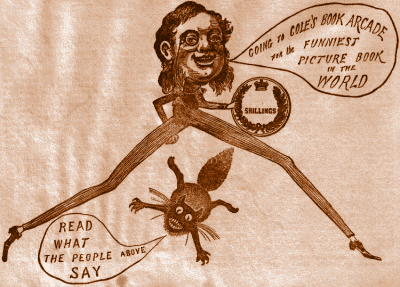

If you search through the World you will not get a book that will so please a child, if you pay £100 or even £1000 for it. To parents, Grandparents, Uncles, Aunts, and Friends—Every Good Child should be given one of these Books for being Good. Every Bad Child should be given one to try to make it Good.

|

|

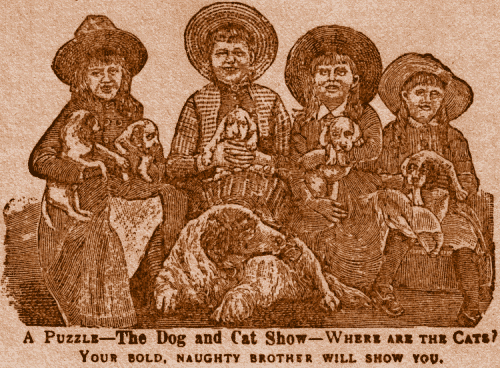

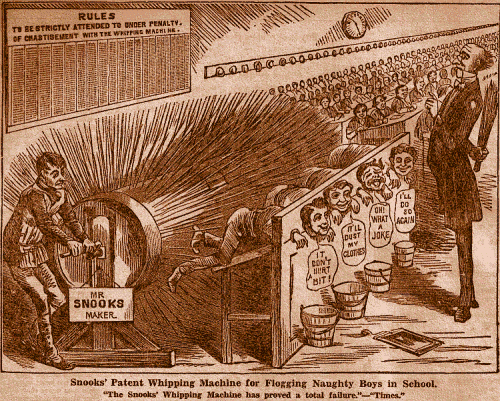

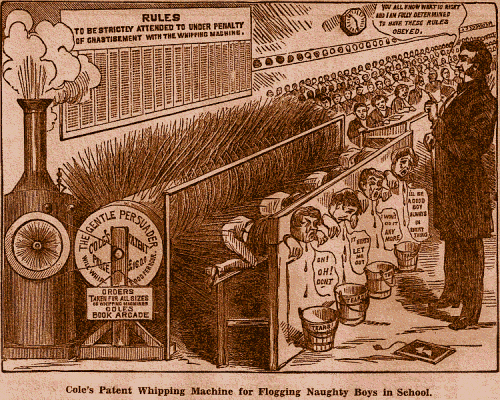

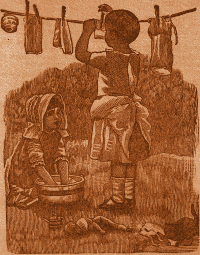

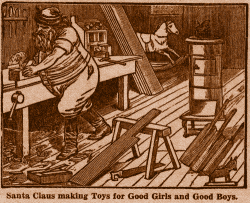

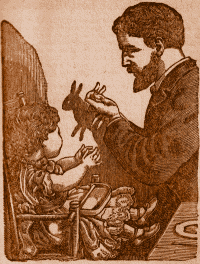

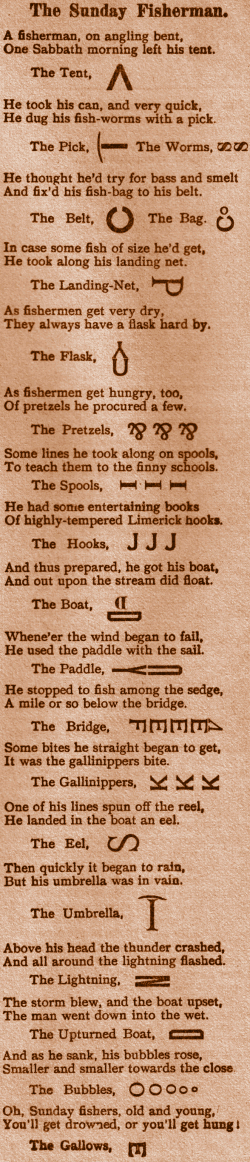

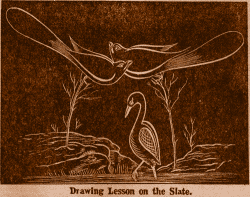

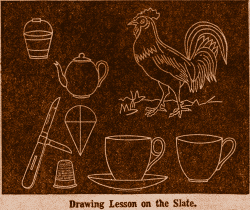

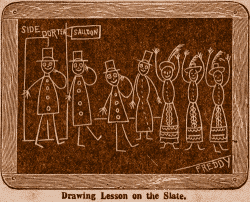

BABY RHYMES Baby Going to Bed 4 Baby, Getting up 5 This Pig Went to Market 6 Baby Riding 6 Naughty Baby 7 LITTLE CHILDREN'S STORIES Tom Thumb's Alphabet 8 Sing a Song-a-Sixpence 8 A Apple Pie 8 Captain Duck 8 Hey-Diddle-Diddle 9 GIRL LAND Cry-Baby Belle 10 A Naughty Little Girl 10 Paulina Pry 10 Tearful Annie 10 Hattie's Birthday 11 Youth and Age 11 A Lost Child 11 Little Mary 11 Girl and Angel 11 Girl Who Wouldn't go to Bed 12 Girl That Beat Her Sister 12 The Sulky Girl 12 Girl Who Sucked Her Fingers 12 The Greedy Little Girl 12 Girl Who Played With Fire 12 The Vulgar Little Lady 12 Peggy Won't 13 The Wonderful Shadows 13 Little Bo-Peep 14 Pammy Was A Pretty Girl 14 The Little Husband 14 I'm Governess 14 Meddlesome Matty 15 Girl Who Spilled the Ink 15 Girl Who Was Always Tasting 15 Sally the Lazy Girl 15 Girl Who Wouldn't Comb Her Hair 15 The Nasty Cross Girls 15 Little Red Riding Hood 16 I'm Grandmama 16 The Babes in the Wood 16 Cinderella 17 The Three Bears 17 Bluebeard 17 My Girl 18 My Little Daughter's Shoes 18 The Old Cradle 18 A Little Goose 18 Girls 19 Girls Names 19 Vain Sarah 19 Several Kinds of Girls 19 Jumping Jennie 20 I Don't Care 20 Little Miss Meddlesome 20 Careless Matilda 20 Forty Little School Girls 21 Funny Monkeys 21 Tangle Pate 22 A Careless Girl 22 The Naughty Girl 22 Mopy Maria 22 Disobedient May 22 Sluttishness 22 Jane Who Bit Her Nails 22 Poking Fun 22 The Pin 23 Stupid Jane 23 Pouting Polly 23 Untidy Emily 23 Maidenhood 24 Girls That Are in Demand 24 Girls' Names 24 Name of Kate 24 Girl-Scolding Machine 25 Jenny Lee 26 Work Before Play 26 Lucy Grey 26 Mary Had a Little Lamb 26 We Are Seven 27 The poor But Blind Girl 27 Grace Darling 27 The Tidy Girl 27 Ruby Cole 28 BOY LAND Vally Cole 29 Tom The Piper's Son 30 House That Jack Built 31 Simple Simon 31 Ten Little Niggers 31 Jack the Giant Killer 32 Jack and the Beanstalk 32 Hop-o-my-Thumb 33 Tom Thumb 33 Naughty Boys 34 Dirty Jack 35 Mischievous Fingers 35 Boy Stealing Apples 35 Playing With Fire 35 Wicked Willie 36 Rude, Bad, Naughty Boy 36 Little Chinky Chow 37 That Nice Boy 38 A Wicked Joking Boy 38 Jack the Glutton 39 Tom the Dainty Boy 39 A birds Nest Robber 39 A Cruel Boy 39 Boy Whipping Machine 40 - 41 DOLLY LAND Puss's Doll 42 Pretty Doll 42 Dolly and I 43 Dolly's Broken Arm 43 Polly and Her Dolly 43 Singing to Dolly 44 My Dolly 44 Dolly's Asleep 44 Lost Dolly 45 Talking To Dolly 45 Darling Dolly 45 Ten Little Dollies 46 Washing-Day Troubles 47 New Tea Things 47 Doll Dress Making 48 Dolly Town 48 The Lost Doll 48 Dolly's Counterpane 48 Sewing For Dolly 48 My Little Doll Rose 48 The Wooden Doll 48 Buy My Dolls 48 Dolly's Doctor 49 Dolly's Broken Nose 49 The Dead Dolly 49 The Soldier Dolly 49 Christening Dolly 50 Maggie's Talk to Dolly 50 Minnie's Talk to Dolly 50 |

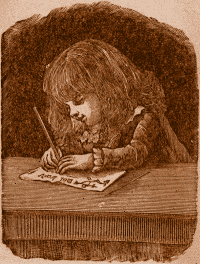

My Dolly

50

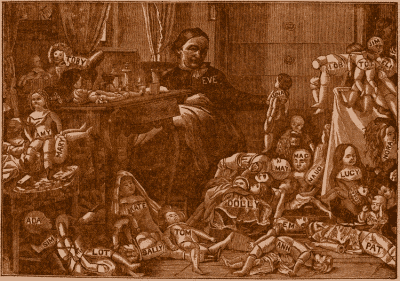

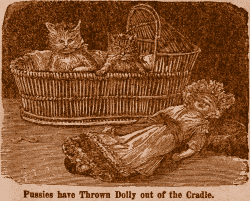

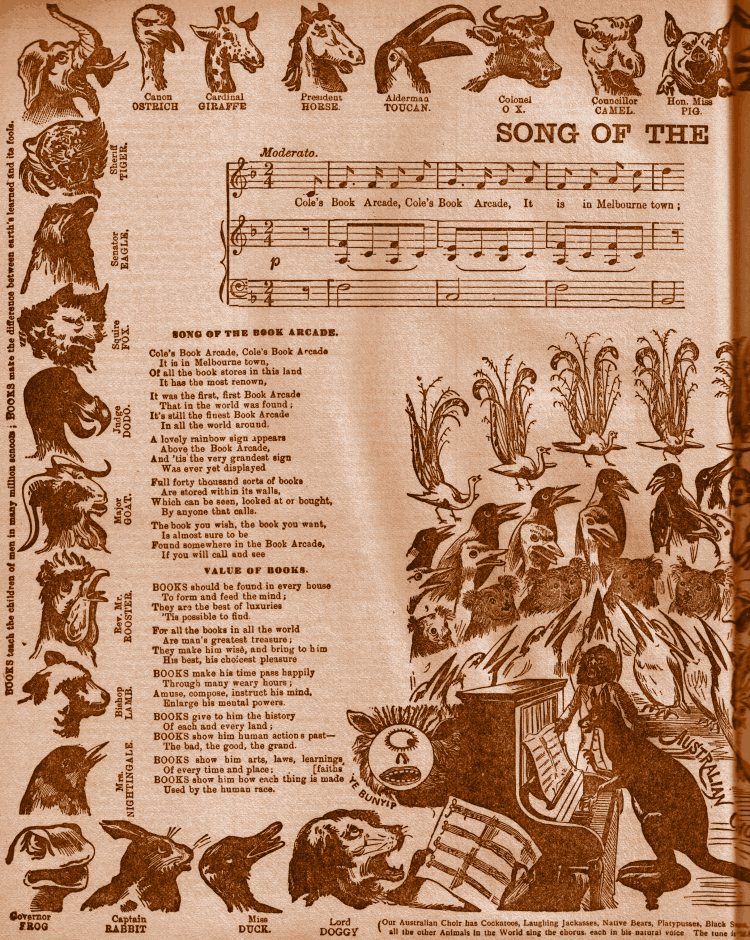

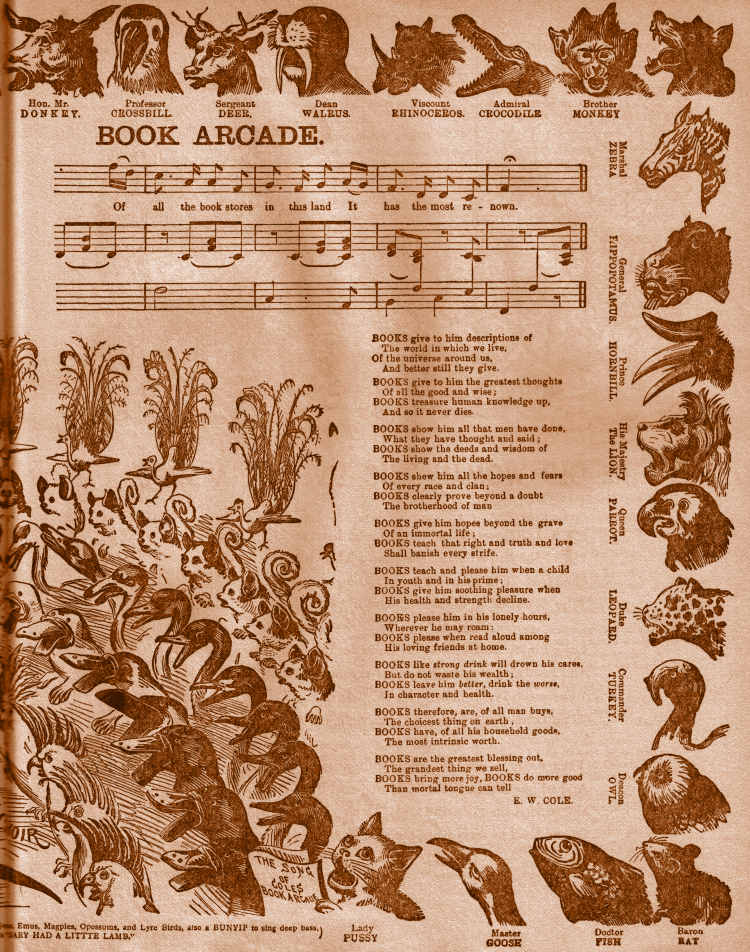

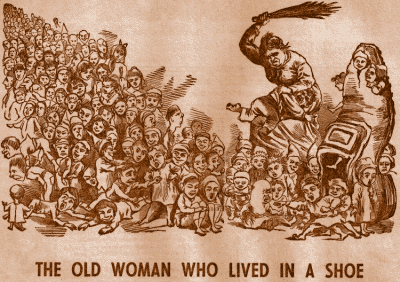

Dolly's Wedding 50 Grandmamma's Visit 51 Lucy's Dolls 51 The Doll Show 52 A Doll's Adventures 53 Story of a Doll 53 I'm Homesick Dolly Dear 54 A Thousand Names For Dollies and Babies 55 , 56 , 57 NAUGHTINESS LAND Good Mamma 58 How They Made Up 58 Cross Patch 58 Sulky Sarah 58 A New Year's Gift 59 Angry Words 59 Love One Another 59 Anger 60 Girl That Beat Her Sister 60 Little Dick Snappy 60 Where Do You Live 61 Govern Your Temper 61 The Ragged Girl's Sunday 62 Foolish Fanny 62 Pride 63 Finery 63 A Fop 63 Greedy Ned 64 Greedy Girl 64 Greedy Richard 64 Story Of an Apple 64 The Plum Cake 65 The Glutton 65 Hoggish Henry 65 Selfishness 65 Truthful Dottie 66 False Alarms 66 Girl That Told A Lie 66 Idle Mary 67 Lazy Sal 67 The Work Bag 67 The Two Gardens 67 Doing Nothing 67 Lazy Sam 68 The Beggar Man 68 Lazyland 68 The Lazy Boy 69 The Sluggard 69 Idle Dicky and the Goat 69 Come and Go 69 The Cruel Boy 70 Story of Cruel Fred 70 The Worm 70 No One Will See Me 71 Boy and His Mother 71 Boys and the Apple Tree 72 Thou Shalt Not Steal 72 The Thief 72 The Thieves' Ladder 73 SANTA CLAUS LAND Santa Claus Land 74 A Visit From St. Nicholas 75 What Santa Claus Brings 75 Little Mary 75 Christmas 75 Christmas Eve Adventure 76 Little Bennie 76 Old Santa Claus 77 Night Before Christmas 77 Annie and Willie's Prayer 78 Budd's Stocking 79 Christmas Morning 79 Nellie And Santa Claus 80 Hang Up Baby's Stocking 80 PLAY LAND Rabbit on the Wall 81 Little Romp 81 Tired of Play 82 The Lost Playmate 82 In The Toy Shop 83 Playing Store 83 Neat Little Clara 83 Hide and Seek 83 Little Sailors 84 Come Out to Play 84 Mud Pies 84 Hay Making 84 Johnny the Stout 85 Training Time 86 Playtime 87 Romping 87 Nurse's Song 87 Swinging 88 Skating 88 The skipping Rope 88 The Baby's Debut 89 READING LAND Reading 90 Mrs Grammar's Ball 90 Grammar in Rhyme 90 Reading Land 91 WRITING LAND Little Flo's Letter 92 The First Letter 92 Baby's Letter to Uncle 92 Nell's Letter 92 Two Letters 92 Going to Write to Papa 93 Papa's Letter 93 Polly's Letter to Ben 94 The Sunday Fisherman 95 Essay on Pictures 96 DRAWING LAND The New Slate 97 Learning to Draw 98 A Lesson in Drawing 99 OLD MEN TALES Old Man and His Wife 100 John Ball Shot Them All 100 Funny Old Man 100 Strange Men 100 Jack Sprat 101 Cross Old Man 101 Very Funny Men 101 Utter Nonsense 102 History Of John Gilpin 103 Australian Native Choir 104 OLD WOMEN TALES Woman Who Lived in a Shoe 106 Mother Goose 107 Old Women of Stepney 107 Funny Old Women 108 Old Woman Who Went Up in a Basket 108 Twenty-six Funny Women 109 |

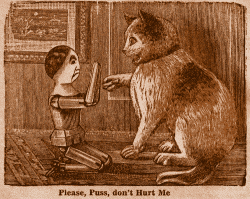

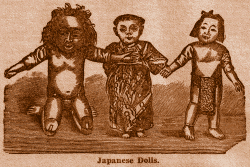

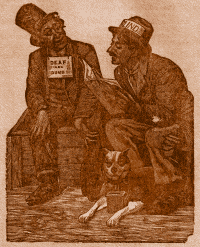

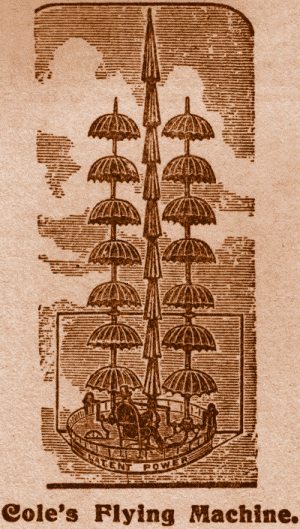

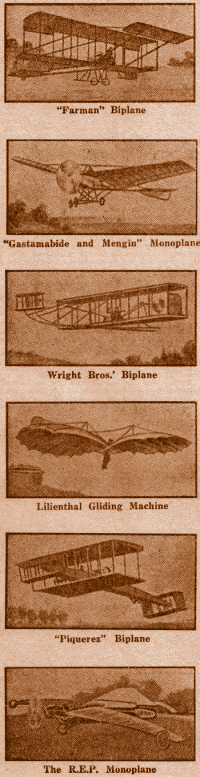

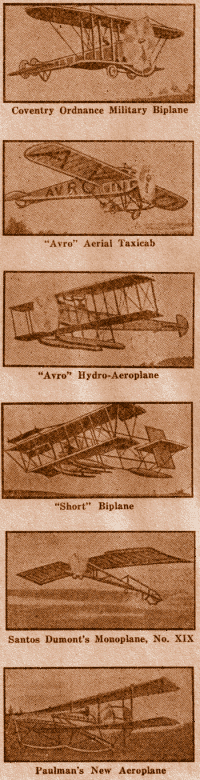

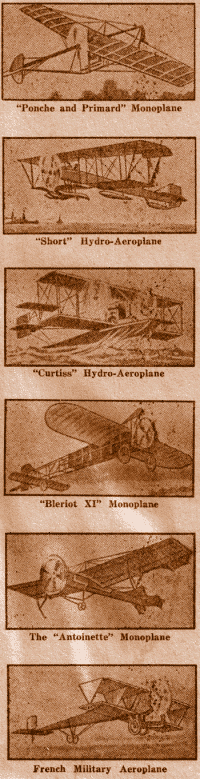

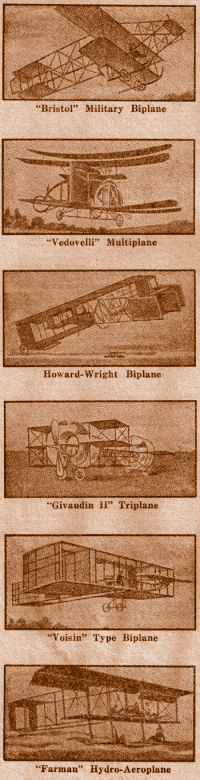

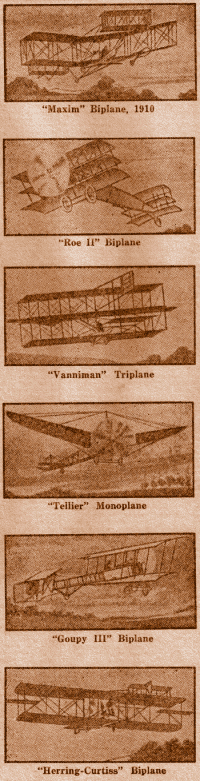

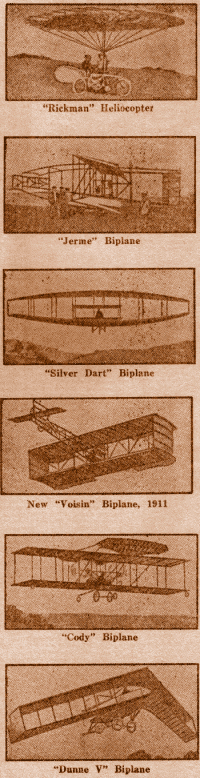

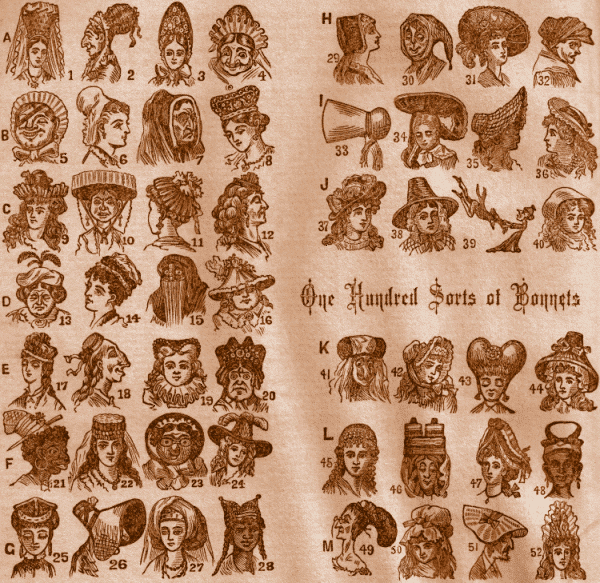

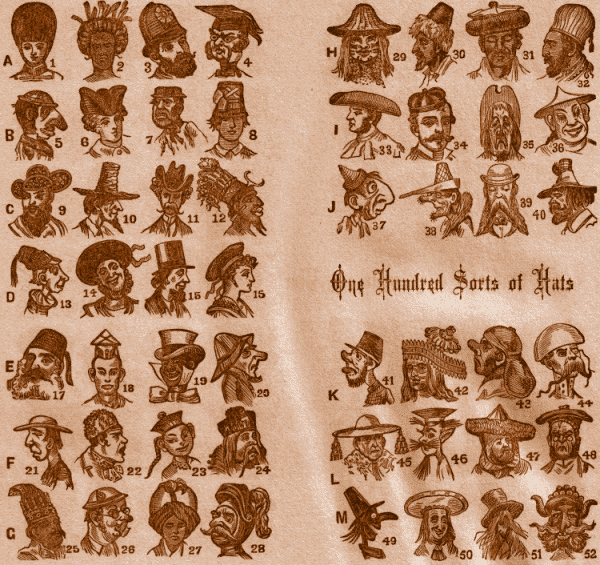

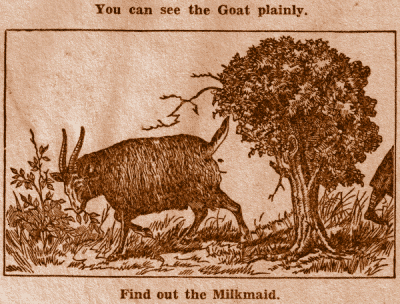

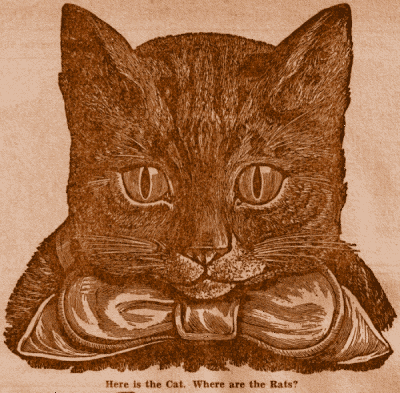

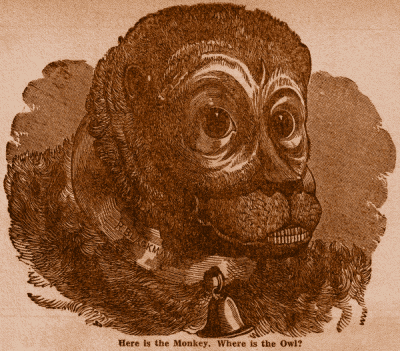

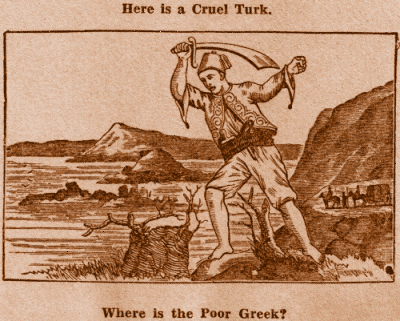

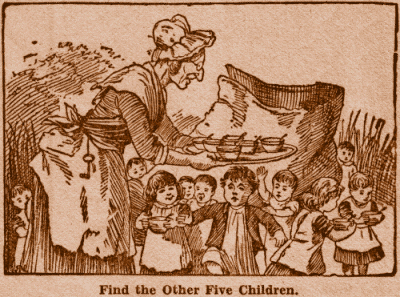

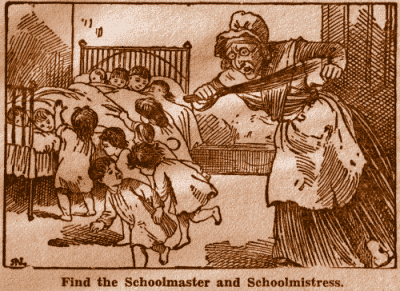

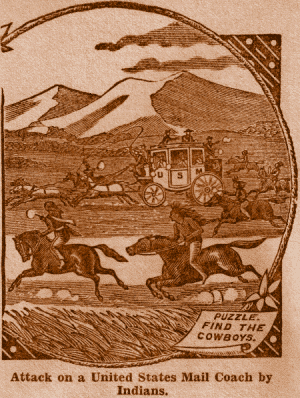

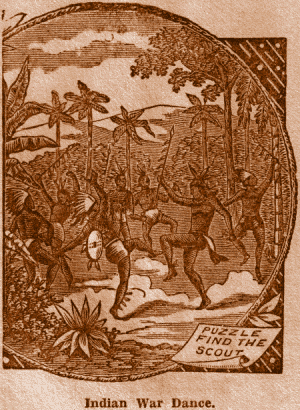

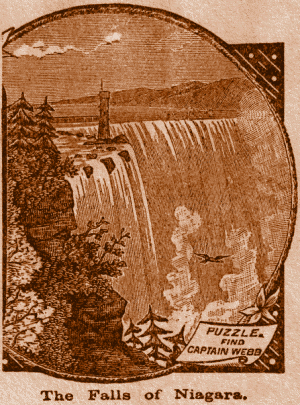

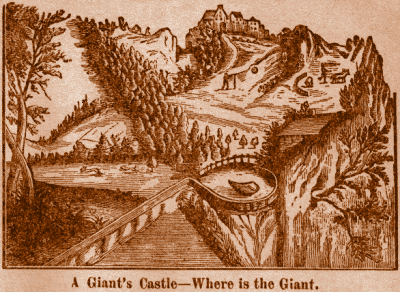

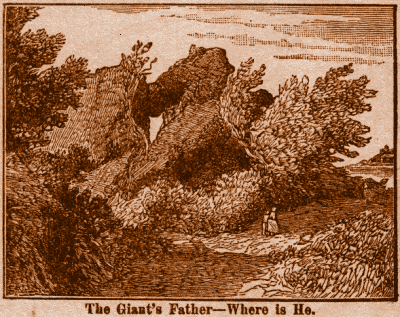

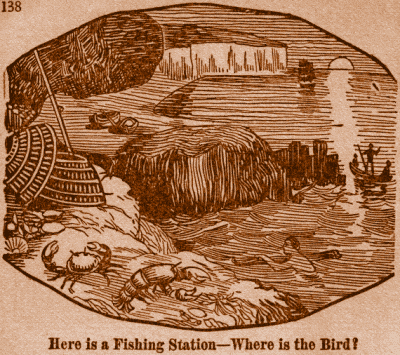

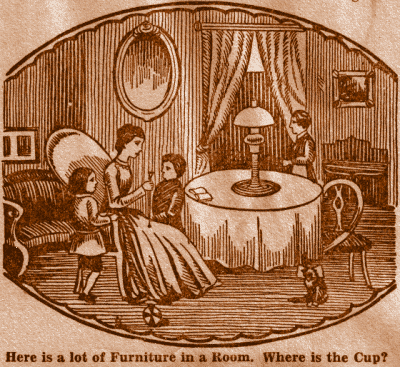

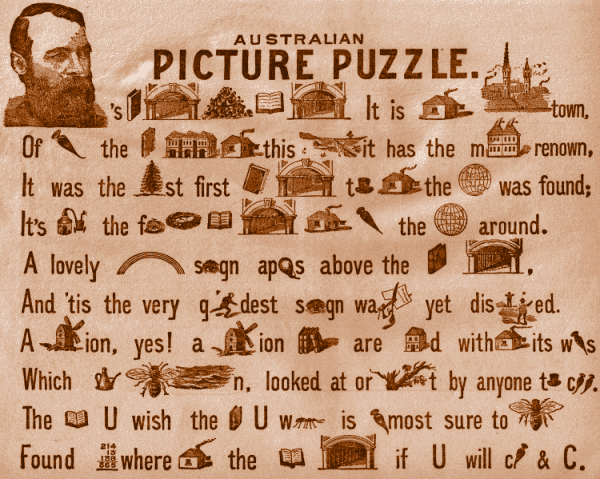

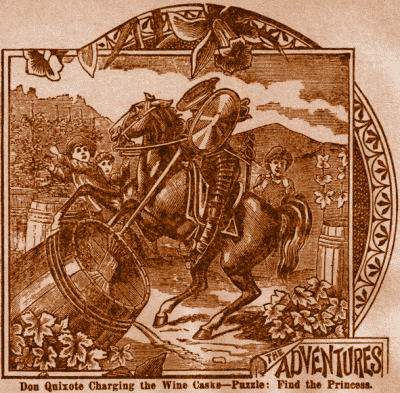

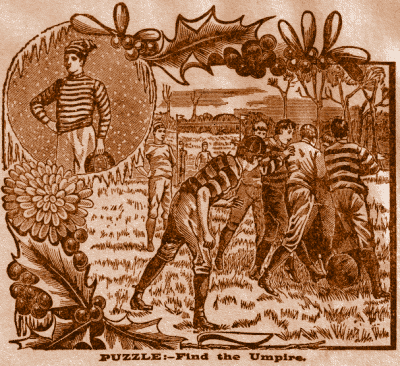

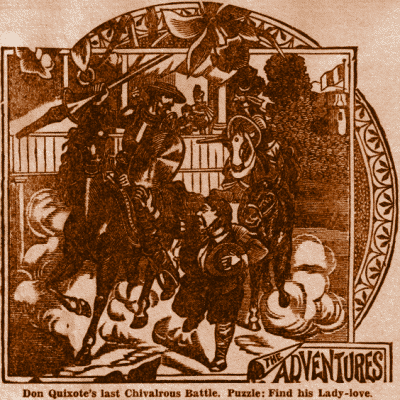

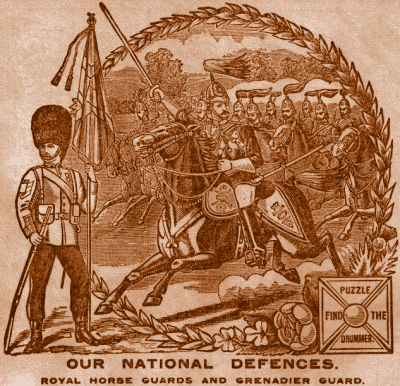

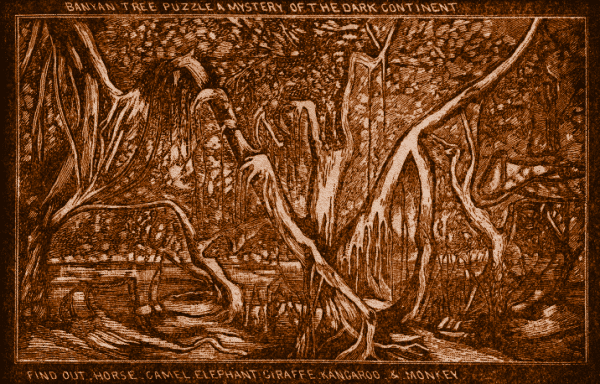

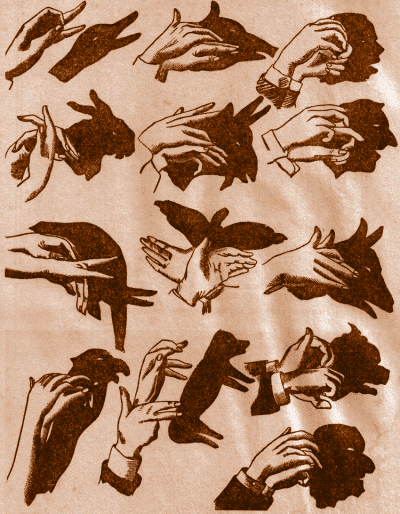

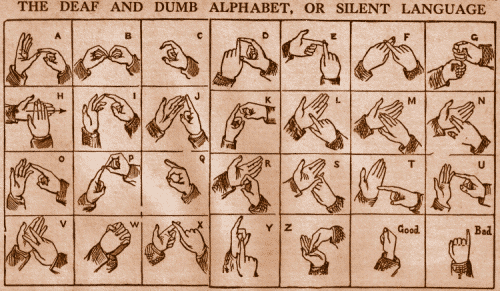

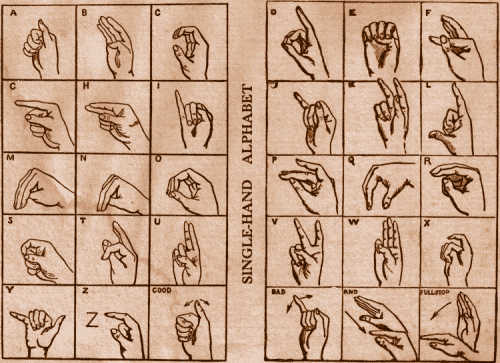

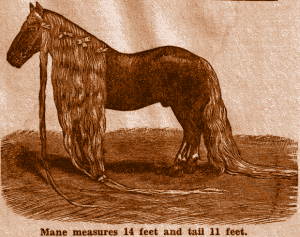

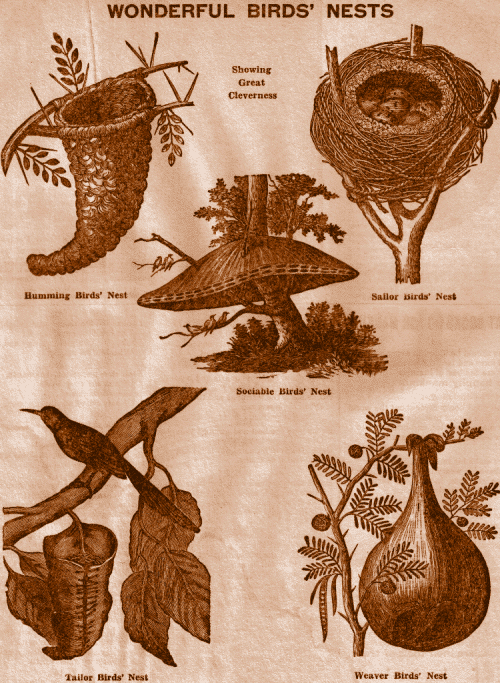

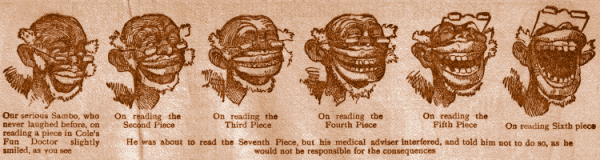

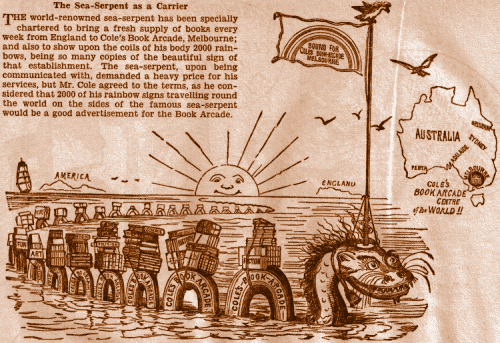

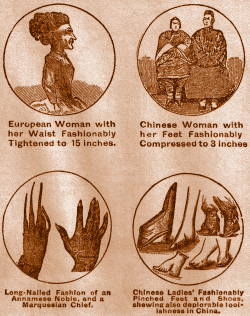

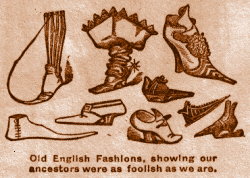

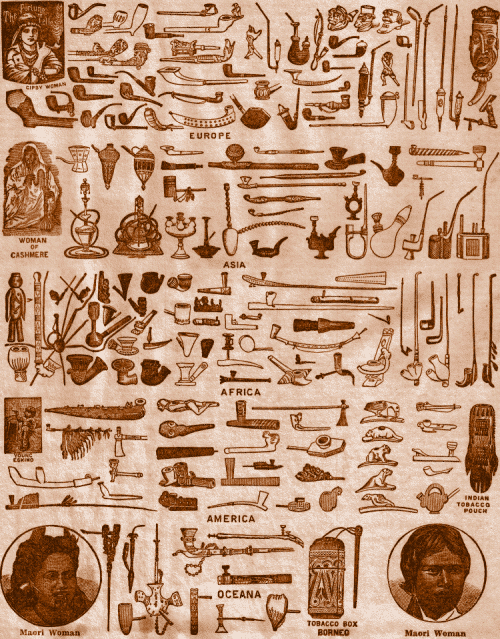

TRAVELLING LAND Forty Ways of Travelling 110 - 113 Flying Machines 114 - 117 NAME LAND Boys' Names 118 Girls' Names 119 GAME LAND Cole's Game of Hats and Bonnets 120 - 123 Riddles and Catches 124 - 127 Picture Puzzles 128 - 143 Shadows on the Wall 144 Deaf and Dumb Alphabet 145 Language of Flowers 146 Kindness to Animals 147 Funny Australian Natives 148 - 149 PUSSY LAND My Pussy 150 Pussy-Cat and Mousey 150 Puss and the Monkey 150 Mary's Puss Drowned 150 Dame Trot's Puss 151 Daddy Hubbard's Cat 152 Story of a Little Mouse 153 Tom, Puss, and the Rats 154 Puss in Boots 155 Monkey and the Cats 155 Dick Whittington 155 More Pussy Land 156 The White Kitten 157 Little Pussy 158 Puss and the Crab 158 Puss in the Corner 159 Tabby 159 Old Puss 159 Dead Kitten 160 My Own Puss 161 Putting Kitty to Bed 161 DOGGY LAND Mother Hubbard and Dog 162 Puss and Rover 163 No Breakfast for Growler 163 Poor Old Tray 163 GOAT LAND O'Grady's Goat 164 The Goat and the Swing 164 MONKEY LAND Meddlesome Jacko 165 A Fruitless Sorrow 165 GEE-GEE LAND The Wonderful Horse 166 The Horse 166 Good Dobbin 166 Horse Sentenced to Die 167 The Arab and His Horse 167 Farmer John 168 DONKEY LAND The Cottager's Donkey 169 Old Jack the Donkey 169 Poor Donkey's Epitaph 169 MOO-MOO LAND The Cow and the Ass 170 The Cowboy's Song 171 That Calf 171 BA-BA LAND The Lost Lamb 172 The Pet Lamb 172 - 173 PIGGY LAND The Pig is a Gentleman 174 Five Little Pigs 174 The Self-willed pig 174 Three Naughty Pigs 175 The Spectre Pig 175 The Chinese Pig 176 Dame Crump and Her Pig 176 Old Woman and Her Pig 177 The Three Little Pigs 177 BUNNY LAND Disobedient Bunny 178 The Wild Rabbits 178 The Pet Rabbit 178 The Little Hare 179 The Poor Hunted Hare 179 Epitaph on a Hare 179 RAT LAND Pied Piper of Hamelin 180 Wicked Bishop Hatto 181 MOUSEY LAND The Three Mice 182 The Foolish Mouse 182 Run, Mousey, Run! 182 The Gingerbread Cat 182 A Clever Mother Mouse 183 The Mouse's Call 183 The Foolish Mouse 183 FROGGY LAND The Foolish Frogs 184 Marriage of Mr. Froggie 184 Frogs at School 184 Frog That Went a Wooing 185 Mixed Animal Land 186 - 187 The Squirrel 188 Wonderful Bird Nests 189 Cole's Poems on Books 190 COMIC ADVERTISER Serious Sambo 191 Laughter as a Medicine 191 Man Made to Laugh 191 Josh Billings' Prayer 191 Fun Better Than Physic 192 Fun About Music 193 Going to Coles' Book Arcade 194 - 195 Wonderful Sea Serpent 196 Funny, Foolish and Useful Fashions 197 - 201 Boy Smoking 202 - 203 Narcotics and Intoxicants 204 Pipes of the World 205 |

|

READER—There are only 365 pieces mentioned in this index, but

the

Book contains 2,000 pieces and pictures, large and small. It is a

complete cyclopoedia of child-lore, and first-class kindergarten

book—to amuse and teach at the same time. No child's book

ever published

has been, nor is now, so great a favourite as this one.

|

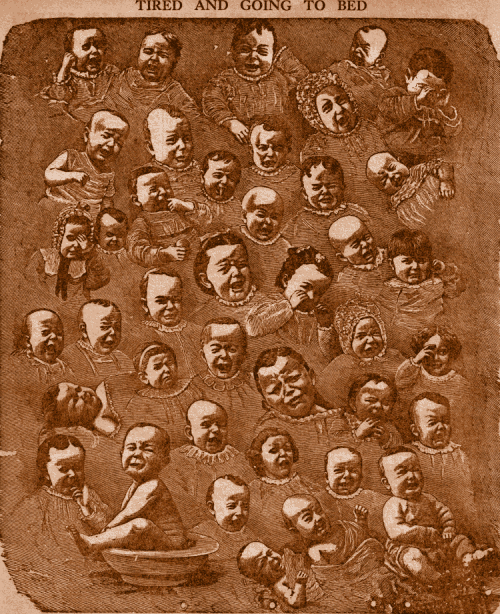

Page 4—Baby Rhymes

A Piece of Poetry for Mother and Father to

Read

|

I suppose if all the children, Who have lived through ages long, Were collected and inspected They would make a wondrous throng.

Oh the babble of the Babel!

Some have never laughed nor spoken,

And indeed, I wonder whether,

Think of all the men and women

And of all of them not any

|

Page 5—Baby Rhymes

|

Who will wash their smiling faces? Who their saucy ears will box? Who will dress them and caress them? Who will darn their little socks?

Where are arms enough to hold them?

Little happy Christian children,

Little princes and princesses,

Only think of the confusion

Oh the babble of the Babel!

|

Page 6—Children's Rhymes

|

|

|

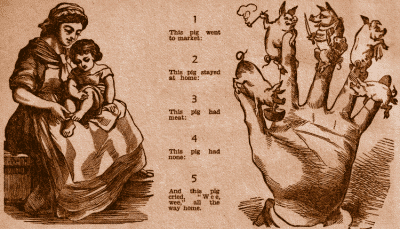

1. This pig went to market: 2. This pig stayed at home: 3. This pig had meat: 4. This pig had none: 5. And this pig cried, "Wee, wee," all the way home.

|

|

Here sits the Lord Mayor! (forehead)

|

|

Ring the bell! (giving its hair a pull)

|

|

(Eye) Bo Peeper! (Nose) Nose dreeper!

|

|

1. Let us go to the wood, says this pig;

|

|

To market, to market, to buy a fat pig;

|

|

Ride baby, ride, pretty baby shall ride,

|

|

Ride a cock-horse to banbury-cross,

|

|

This is the way the ladies ride;

|

|

Clap hands, clap hands,

|

|

You shall have an apple,

|

|

Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake, baker's man!

|

|

Churn, butter, churn! come, butter, come!

|

|

When Jacky's a very good boy,

|

Page 7—Children's Rhymes

|

Hickup, hickup, go away!

|

|

Dance, little baby, dance up high,

|

|

Dance to your daddy,

|

|

Danty baby diddy,

|

|

Hush-a-bye, a baa lamb,

|

|

Bye, baby bunting,

|

|

Hush-a-bye baby, on the tree top,

|

|

Rock-a-bye baby, thy cradle is green;

|

|

My dear cockadoodle, my jewel, my joy,

|

|

Baby, baby, lay your head

|

|

Hush thee, my babby,

|

|

Oh, my lady! my lady! my lady!

|

|

Baby, baby ope your eye,

|

|

Wash hands, wash,

|

|

Comb hair, comb,

|

|

My pretty baby-brother

Whenever I come near,

|

|

He opens his mouth when he kisses you;

|

|

Come, my darling, come away,

|

|

See-saw sacradown,

|

|

Baby, baby Charlie,

Patting with his soft hands,

Do not cry, dear Annie,

Or his little hands will

Kiss the baby, darling,

|

Page 8—Little Children's Stories

|

A was an archer, who shot at a frog;

|

|

Sing a song-a-sixpence,

|

|

If I'd as much money as I could spend,

|

|

Cock-a-doodle-doo,

|

|

Hot-cross buns! Hot-cross buns!

|

|

Rabbit, rabbit, rabbit-pie!

|

|

A apple pie;

|

|

Rub a dub, dub,

|

|

Hey ding a ding, what shall I sing?

|

|

Barber, barber, shave a pig,

|

|

Punch and Judy fought for a pie;

|

|

Pease pudding hot,

|

|

A little bit of powdered beef,

|

|

The barber shaved the mason,

|

|

I saw a ship a-sailing,

|

|

Little Tee Wee' he went to sea

|

Page 9—Children's Rhymes

|

Jack be nimble, and Jack be quick;

|

|

Jack Sprat had a cat,

|

|

Little Jack Horner sat in the corner,

|

|

Little Tom Tucker

|

|

Georgie Porgie, pudding and pie,

|

|

See-saw, Margery Daw,

|

|

Little lad, little lad, where wast thou born?

|

|

Handy Spandy, Jack-a-dandy,

|

|

Deedle, deedle, dumpling, my son John

|

|

Jack and Jill went up the hill,

|

|

Willie drew a little pig,

|

|

Baa, baa, black sheep,

|

|

Hey diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle,

|

|

"Hey! diddle diddle, |

|

[*]

Our friend, the Quaker, holds that the last verse is the proper

one, as it is the truest; but the wonderful is taken out of it, and

children, accordingly, prefer the first. There is nothing wonderful

in the cow jumping "under" the moon, but there is in the cow jumping

"over" the moon, so with the black-birds baked in a pie. It is the

fact of their singing when the pie is opened that pleases the

children—'twas the wonder of the thing; so with the freaks of

Mother Hubbard's Dog, etc. In nearly all nursery rhymes it is the

ludicrous and wonderful that arrests the attention and pleases. E. W. Cole

|

|

There was a little boy, went into a barn,

|

|

Tweedle-dum and tweedle-dee

|

|

Baby and I

|

|

High diddle doubt, my candle's out,

|

|

Rowsty dowt, my fire's all out,

|

|

We're all in the dumps,

|

|

Blow, wind, blow! and go, mill, go!

|

|

Come, let's to bed, says Sleepy-head

|

|

Go to bed first,

|

Page 10—Girl Land

|

Cry-baby Belle

She'll cry if she happens

If the food set before her

If she wants to go out

She screams in the morning

She cries when she's sick,

She always is fretful,

|

|

My sweet little girl should be careful and mild,

That dear little face, which I like so to kiss,

Remember, tho' God is in heaven, my love,

If I am not with you, or if it be dark,

Then dry up your tears, and look smiling again

|

|

Paulina Pry

She would not eat

They heard her cry

|

|

Poor little Annie, you will find,

The other day when Ferdinand—

Her father grieved, said: "This must cease

He set to work that very day,

It was in truth a great success;

With every relative who came,

Annie not long could this endure;

|

Page 11—Girl Land

|

Oh! This is a happy, beautiful world!

Yes, six, and father has bought me a book,

My kitty sat quietly near the fire

Ah me! if Kit could only talk,

I dressed all up in grandma's cap,

My mother softly kissed my cheek,

My birthday song is a merry one,

|

|

A funny thing I heard to-day,

And, through the open play-room door,

And Lillie said—(and I agreed

"But, Lillie," urged the elder one,

|

|

"I would not be a girl," said Jack,

"I would not be a boy," said May,

|

|

"I'm losted! Could you find me, please?"

"Tell me your name, my little maid:

"But, dear," I said, "what is your name?"

"My mamma never scolds," she moans,

Anna E. Burnham

|

|

Here stands little, little Mary,

Who so gay as Mary?

Household pet is Mary—

Mischief-loving Mary,

|

|

As Peter sat at Heaven's gate

"What claim hast thou to enter here?"

"Enough," the hoary guardian said,

|

Page 12—Naughty Girls

|

Once I knew a little girl,

At night she'd stop upon the stairs,

The bed at last they tuck'd her in,

|

|

Go, go, my naughty girl, and kiss

What! little children scold and fight

I can't imagine for my part,

|

|

Let dogs delight to bark an bite,

But children you should never let

|

|

Why is Mary standing there,

Come here, my dear, and tell me true,

When, then, indeed, I'm grieved to see

Oh! how much better it appears,

|

|

What! cry when I wash you! not love to be clean?

|

|

A little girl, named Mary Kate,

A silly habit she's acquired

Her play-companions used to laugh,

|

|

This is Nelly Pilfer;

They caught the greedy Nelly

|

|

Little Polly Flinders,

|

|

I knew a greedy little girl,

Five dolls she had—one was black,

Now this was wicked of the child,

|

|

Mamma, a little girl I met,

Poor little girl! and don't you know

For once, when nobody was by her,

In vain she tried to put it out,

For many months before 'twas cured,

|

|

Little Miss Consequence strutted about,

|

|

"But, mamma, now," said Charlotte, "pray don't you believe

"I ride in my coach, and have nothing to do.

"Then servants are vulgar and I am genteel;

"Gentility, Charlotte," her mother replied,

"Not all the fine things that fine ladies possess

|

Page 13—Naughty Girls

|

"I won't be dressed, I won't, I won't!"

Peggy then frowned and set her lips

The minutes passed, and Peggy sighed,

Then mother came, and firmly said,

"So now to bed, my little maid,

Oh, for the tears that Peggy shed!

|

|

"Mamma! I see something

"It is Mamma's shadow

"These wonderful shadows

"And when you are out

"Now hold up your mouth,

Mary Lundie

|

Page 14—Naughty Girls

|

Little Bo-Peep has lost her sheep,

Little Bo-Peep fell fast asleep,

Then up she took her little crook,

It happened one day, as Bo-Peep did stray

She heaved a sigh, and gave by-and-by

|

|

Mary had a little lamb

So Mary took that little Lamb

|

|

Pemmy was a pretty girl,

Pemmy had a pretty nose,

Pemmy had a pretty song,

|

|

I had a little husband,

I bought a little horse,

I gave him some garters,

|

|

Now children dear, you all come near

For now I'm Governess you'll find,

And Sarah White sit down at once,

And find your thimble Maggie More,

|

|

And you Kate Ross, stop pinching there, Don't scratch! nor pull your sister's hair; And you, you naughty Lucy Moyes, Must not be talking to the boys.

And Bridget Mace don't make that face;

Now I want all good children in my school,

Yes all be good and learn your lessons well,

|

|

Little Nellie Nipkin, brisk, and clean, and neat,

|

|

Dingty diddledy, My mamma's maid,

|

|

I have a little doll, I take care of her clothes;

|

|

As Tommy Snooks and Bessy Brooks

|

|

Little Betty Blue, lost her left shoe,

|

|

Cross patch, draw the latch,

|

|

Hinx, minx! the old witch winks,

|

|

Doodle, doodle, doo,

|

|

The girl in the lane that couldn't speak plain,

|

|

Mary, Kate, and Maria went down as agreed,

A young rabbit also, tho' seeming to dose,

|

Page 15—Naughty Girls

|

One ugly trick has often spoiled

Sometimes she'd lift the teapot lid

Her grandma went out one day,

Forthwith she placed upon her nose

"I know grandmamma would say,

So thumb and finger went to work

Poor eyes, and nose, and mouth beside,

She dashed the spectacles away,

Matilda, smarting with the pain,

|

|

"Oh! Lucy! Fanny! Make haste here!

And Lucy cries, with open eyes,

Mamma comes in: "Heyday! what's this?

|

|

A naughty girl had got no toy,

|

|

Little Miss Baster, of Sunnyside,

|

|

Four naughty little children thought

Their mother who was just next door,

|

|

Her sister would come to the bedside and call,

"The water is boiling, the table is spread,

Then Sally sat up and half opened her eyes,

But though she was lazy, she always could eat,

Her frock was all crumpled and twisted away,

She sauntered about till the old village clock

But soon as she came to the little cake shop,

Again she went on, and she loitered again

The governess frowned as she went to her place,

She hated her reading, and never would write,

|

|

I tell you of a little girl, who would herself have been, |

|

She would have been a pretty child, But, oh! she was a fright— She looked just like a girl that's wild, Yes, quite as ugly, quite; She looked just like a girl that's wild— A frightful ugly sight.

|

|

The school was closed one afternoon,

Some plucked the flowers upon the banks,

And if, perchance, a girl came near,

As Nelly White ran home from school,

"We don't want you," said Lucy Bell,

Then both girls cried, "Tell-tale-tit,"

|

Page 16—Girl's Stories

|

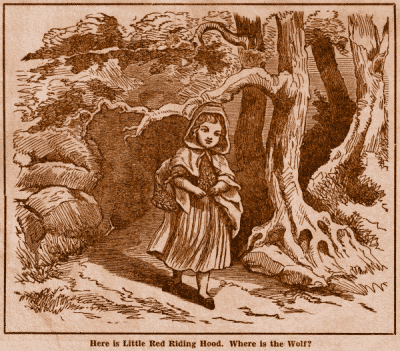

Once upon a time there was a dear little girl whose mother made her a scarlet cloak with a hood to tie over her pretty head; so people called her (as a pet name) "Little Red Riding-Hood." One day her mother tied on her cloak and hood and said, "I wish you to go to-day, my darling, to see your grandmamma, and take her a present of some butter, fresh eggs, a pot of honey, and a little cake with my love." Little Red Riding-Hood loved her grandmother, and was very glad to go. So she ran gaily through the wood, gathering wild flowers and gambolling among the ferns as she went; and the birds all sang their sweetest songs to her, and the bluebells nodded their pretty heads, for everything loved the gentle child. By and by a great hungry Wolf came up to her. He wished to eat her up, but as he heard the woodman Hugh's axe at work close by, he was afraid to touch her, for fear she should cry out and he should get killed. So he only asked her where she was going. Little Red Riding-Hood innocently told him (for she did not know he was a wicked Wolf) that she was going to visit her grandmother, who lived in a cottage on the other side of the wood. Then the Wolf made haste, and ran through the wood, and came to the cottage of which the child had told him. He tapped at the door.

"Who's there?" asked the old woman, who lay sick in bed.

The cruel Wolf did so, and, jumping on the bed, ate the poor grandmother up. Then he put on her night-cap and got into bed. By and by Little Red Riding-Hood, who had lingered gathering flowers as she came along, and so was much later than the Wolf, knocked at the door.

"Who's there?" asked the Wolf, mimicking her grandmother's

voice. So Red Riding-Hood came in, and the Wolf told her to put down her basket, and come and sit on the bed. When Little Red Riding-Hood drew back the curtain and saw the Wolf, she began to be rather frightened and said,

"Dear Grandmamma, what great eyes you have got!"

Alas! she reminded the greedy Wolf of eating.

"All the better to eat you with!" he growled; and, jumping

out of bed, sprang at Red Riding-Hood. But just at that moment Hugh the woodman, who had seen the sweet child go by, and had followed her, because he knew there was a Wolf prowling about the forest, burst the door open, and killed the wicked animal with his good axe. Little Red Riding-Hood clung round his neck and thanked him, and cried for joy; and Hugh took her home to her mother; and after that she was never allowed to walk in the greenwood by herself. It was said at first that the Wolf had eaten the child, but that was not the case; and everybody was glad to hear that the first report was not correct, and that the Wolf had not really killed Little Red Riding-Hood.

|

|

Little Miss Jewel

|

|

Little girl, little girl, where have you been;

|

|

Little Betty Blue lost her pretty shoe;

|

|

Last night when I was in bed,

But she was such a tiny girl,

An I went walking up the street,

And after tea I washed her face;

|

|

A long time ago there lived in an old mansion in the country a rich gentleman and his wife, who had two dear little children, of whom they were very fond. Sad to relate, the gentleman and lady were both taken ill, and, feeling they were about to die, sent for the uncle of the children, and begged him to take care of them till they were old enough to inherit the estates. Now this uncle was a bad and cruel man, who wanted to take the house, the estates, and the money for himself,—so after the death of the parents he began to think how he could best get rid of the children. For some time he kept them till he claimed for them all the goods that should have been theirs. At last he sent for two robbers, who had once been his companions, and showing them the boy and girl, who were at play, offered them a large sum of money to carry them away and never let him see them more. One of the two robbers began coaxing the little boy and girl, and asking them if they would not like to go out for a nice ride in the woods, each of them on a big horse. The boy said he should if his sister might go too, and the girl said she should not be afraid if her brother went with her. So the two robbers enticed them away from the house, and, mounting their horses, went off into the woods, much to the delight of the children, who were pleased with the great trees, the bright flowers, and the singing of the birds. Now, one of these men was not so bad and cruel as the other, and he would not consent to kill the poor little creatures, as the other had threatened he would do. He said that they should be left in the woods to stray about, and perhaps they might then escape. This led to a great quarrel between the two, and at last the cruel one jumped off his horse, saying he would kill them, let who would stand in the way. Upon this the other drew his sword to protect the children, and after a fierce fight succeeded in killing his companion. But though he had saved them from being murdered, he was afraid to take them back or convey them out of the wood, so he pointed out a path, telling them to walk straight on and he would come back to them when he had bought some bread for their supper; he rode away and left them there all alone, with only the trees, and birds and flowers. They loved each other so dearly, and were so bold and happy, that they were not much afraid though they were both very hungry. The two children soon got out of the path, which led into the thickest part of the wood, and then they wandered farther and farther into the thicket till they were both sadly tired, but they found some wild berries, nuts and fruits, and began to eat them to satisfy their hunger. The dark night came on and the robber did not return. They were cold, and still very hungry, and the boy went about looking for fresh fruit for his sister, and tried to comfort her as they lay down to sleep on the soft moss under the trees. The next day, and the next, they roamed about, but there was nothing to eat but wild fruits; and they lived on them till they grew so weak that they could not go far from the tree where they had made a little bed of grass and weeds. There they laid down as the shades of night fell upon them, and in the morning they were both in heaven, for they died there in the forest, and as the sun shone upon their little pale faces, the robins and other birds came and covered their bodies with leaves, and so died and were buried the poor Babes in the Wood.

|

Page 17—Girl's Stories

|

Cinderella's mother died while she was a very little child, leaving her to the care of her father and her step-sisters, who were very much older than herself; for Cinderella's father had been twice married, and her mother was his second wife. Now, Cinderella's sisters did not love her, and were very unkind to her. As she grew older they made her work as a servant, and even sift the cinders: on which account they used to call her in mockery "Cinderella." It was not her real name, but she became afterwards so well known by it that her proper one has been forgotten. She was a sweet tempered, good girl, however, and everybody except her cruel sisters loved her. It happened, when Cinderella was about seventeen years old, that the King of that country gave a ball, to which all the ladies of the land, and among the rest the young girl's sisters were invited. So they made her dress them for this ball, but never thought of allowing her to go.

"I wish you would take me to the ball with you, sisters,"

said Cinderella, meekly.

"Take you, indeed!" answered the elder sister with a sneer,

"it is no place for a cinder-sifter: stay at home and do your work." When they were gone, Cinderella, whose heart was sad, sat down and cried; but as she sorrowful, thinking of the unkindness of her sisters, a voice called to her from the garden, and she went to see who was there. It was her godmother, a good old Fairy. "Do not cry, Cinderella," she said; "you also shall go to the ball, because you are a kind, good girl. Bring me a large pumpkin." Cinderella obeyed, and the fairy touched it with her wand, turned it into a grand coach. Then she turned a rat into a coach-man, and some mice into footmen; and touching Cinderella with her wand, the poor girl's rags became a rich dress trimmed with costly lace and jewels, and her old shoes became a charming pair of glass slippers, which looked like diamonds. The fairy told her to go to the ball and enjoy herself, but to be sure and leave the ball-room before the clock struck eleven. "If you do not," she said, "your fine clothes will all turn to rags again. So Cinderella got into the coach, and drove off with her six footmen behind, very splendid to behold, and arrived at the King's Court, where she was received with delight. She was the most beautiful young lady at the ball, and the Prince would dance with no one else. But she made haste to leave before the hour fixed and had time to undress before her sisters came home. They told her a beautiful Princess had been at the ball, with whom the Prince was delighted. They did not know it was Cinderella herself. Three times Cinderella went to royal balls in this manner, but the third time she forgot the Fairy's command, and heard eleven o'clock strike. She darted out of the ball-room and ran down stairs in a great hurry. But her dress all turned to rags before she left the palace and she lost one of her glass slippers. The Prince sought for her everywhere, but the guard said no one had passed the gate but a poor beggar girl. However, the prince found the slipper, and in order to discover where Cinderella was gone, he had it proclaimed that he would marry the lady who could put on the glass slipper. All the ladies tried to wear the glass slipper in vain, Cinderella's sisters also, but when their young sister begged to be allowed to try it also, it was found to fit her exactly, and to the Prince's delight, she drew the fellow slipper from her pocket, and he knew at once that she was his beautiful partner at the ball. So she was married to the Prince, and the children strewed roses in their path as they came out of church. Cinderella forgave her sisters, and was so kind to them that she made them truly sorry for their past cruelty and injustice.

|

|

Once upon a time three bears lived in a nice little house in a great forest. There was Father Bear, Mother Bear, and Baby Bear. They had each a bed to sleep in, a chair to sit on, and a basin and a spoon for eating porridge, which was their favourite food. One morning the three bears went to take a walk before breakfast; but before they went out they poured the hot porridge into their basins, that it might get cool by the time they came back. Mr and Mrs Bear walked arm-in-arm, and Baby Bear ran by their side. Now, there lived in that same forest a sweet little girl who was called Golden Hair. She, also, was walking that morning in the wood, and happening to pass by the bear's house, and seeing the window open, she peeped in.

|

|

There was no one to be seen, but three basins of steaming hot

porridge all ready to be eaten, seemed to say "Come in and have some

breakfast." So Golden Hair went in and tasted the porridge in all the

basins, then she sat down in Baby Bear's chair, and took up his

spoon, and ate up all his porridge. Now this was very wrong. A tiny

bear is only a tiny bear, still he has the right to keep his own

things. But Golden Hair didn't know any better.

Unluckily, Baby Bear's chair was too small for her, and she broke the seat and fell through, basin and all. Then Golden Hair went upstairs, and there she saw three beds all in a row. Golden Hair lay down on Father Bear's bed first, but that was too long for her, then she lay down on Mother Bear's bed, and that was too wide for her, last of all she lay down on Baby Bear's bed, and there she fell asleep, for she was tired. By-and-by the bears came home, and Old Father Bear looked at his chair, and growled:

"Somebody has been here!" Baby Bear, seeing his chair broken, squeeled out "Somebody has been here, and broken my chair right through!" Then they went to the table, and looked at their porridge, and Father Bear Growled:

"Who has touched my basin?" But the noise they made awoke Golden Hair; she startled out of bed (on the opposite side) and jumped out of the window. The three bears all jumped out after her, but they fell one on the top of the other, and rolled over and over, and while they were picking themselves up, little Golden Hair ran home, and they were not able to catch her.

|

|

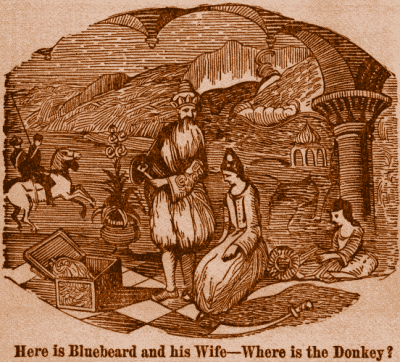

Once there lived in a lovely castle a very rich man called Bluebeard. A short distance off lived an old gentleman with two lovely daughters, named Fatima and Annie. Bluebeard visited their house, and at length proposed to Fatima, was accepted by her, and they were married with great splendour. He took her home with him to his castle, and permitted her sister Annie to reside with her for company for a time. She lived very happily in her new home, her new husband was very kind to her, and allowed her to have everything she wished for, but one day he suddenly told her that business called him away from home, that he should be away some days, and handed her the keys to his wardrobe, treasures, and all parts of the castle, he also gave her one key of a small closet, and told her that she might unlock every door in the castle, but not the closet door, for if she did so, she should not live an hour longer. He then left home fondly kissing her at the door. Her sister and herself returned into the castle, and enjoyed themselves in unlocking room after room, looking over the curiosities, treasures, &c, until Annie became tired and lay down to rest on a rich sofa, and fell asleep. Fatima, as soon as she saw that her sister was asleep, felt a womanly curiosity, an irresistible temptation to unlock the forbidden closet, and take a peep. She tripped lightly up to the door, turned the key in the lock, pushed the door open, and, oh! horror! there were five or six dead ladies lying in the closet, with their marriage rings on their fingers. She at once concluded that they were Bluebeard's previous wives, she let the key drop in her fright into the blood on the floor, she picked it up and attempted to wipe it, but the blood would not come off. She awoke her sister, and they both tried, but they could not get it off, and gave it up in despair. Just then Bluebeard suddenly returned, and asked his wife if she could please to hand him the keys. She trembling did so. He said "How came the blood on the closet key? You have disobeyed me, and shall die at once." She begged a few minutes to say her prayers and just as he was going to chop her head off, her two brothers arrived at the castle, burst open the door, killed the cruel wretch, and rescued their sisters.

|

Page 18—Girl Land

|

A little corner with it's crib.

A little plate all lettered round,

A little doll with flaxen hair.

A little school day after day,

A little muff for wintry weather,

A little while to dance and bow,

A little walk in leafy June,

A little ceremony grave,

|

|

There was a little girl,

|

|

Two little rough-worn, stubbed shoes

Of very homely fabric they,

And yet this little, worn-out pair

This mottled leather, cracked with use,

Search through the wardrobe of the world!

And why? Because they tell of her,

They tell me of her merry laugh;

They tell me that her wavering steps

High hills and swift descents abound;

Sweet little girl! be mine the task

And when my steps shall faltering grow,

|

|

And this was your cradle?

Your baby-day flowed

To hint at an infantine

Ay, here is your cradle,

It is Hope gilds the future—

Is life a poor coil

Then smile as your future

Ay, here is your cradle!

Frederick Locker

|

|

The chill November day was done,

And hopelessly and aimlessly

And shivering on the corner stood

Her dimpled face was stained with tears;

And one hand round her treasures,

"Tell me your street name and number, pet;

"He came and played at Miller's steps;

I've walked about a hundred hours,

"But what's your mother's name?

"But what is strange about the house,

Oh! dear, I ought to be at home,

"And there's a bar between, to keep

The sky grew stormy, people passed,

I spied a ribbon about her neck.

A card with number, street, and name!

And so I wear a little thing

Eliza S. Turner

|

Page 19—Girl Land

|

There's the pretty girl,

There's the dowdy girl,

There's the tender girl,

There's the lazy girl,

There are many others,

|

|

There is a strange deformity

|

|

Oh, Sarah mine, hark to my song

You know my fond heart beats for you

The day's not far when you'll be mine—

The tender fates shall crown your lot,

With bridal altar draped with flowers

There's nothing I'll not do for you

I must to sleep, Sal, soda you,

|

|

A good girl to have—Sal Vation.

|

Page 20—Girl Land

|

Jennie has a jumping-rope

She knocked the vases from the shelf,

Against the wall, against the door

She jumped so high, she jumped so hard,

|

|

Matilda was a pretty girl,

She once her lessons would not learn,

As she advanced to riper years,

She grew a woman, and for life

Duties neglected, warnings spurn'd,

Still on she went from bad to worse,

Afflictions came, and death in view,

Could you have then Matilda seen,

|

|

Little Miss Meddlesome

Out goes the spools spinning

Little Miss Meddlesome

She turns over the ottoman,

But here comes the nurse,

|

|

"Again, Matilda,

Your needles, pins, your thread,

Fie, fie, my child!

I'm now resolv'd

In vain Matilda wept,

Arriv'd at Austere Hall,

"You read, and write,

But very careless,

The little girl

The lady harsh replies,

As thus Matilda sat,

Her hair and dress neglected,

"Here, child," she said,

A polyanthus bright,

Entangled were

She took a thread,

Well-order'd silks

She sigh'd, and melted

A pretty maiden, clean,

"My name is Order,

She took the silks,

Matilda now resumed

She leaves the room,

"Why this is well!

And now amuse yourself,

At all her tasks

With tears and sighs

No longer Lady Rigid

And when the day

"You quit me, child,

And now, my dear,

"From me," Disorder asked,

|

Page 21—Girl Land

|

Forty little school girls, running, but not flirty;

Thirty little school girls swimming the river Plenty;

Twenty little school girls jumping in velveteen;

Nineteen little school girls going out a-skating;

Eighteen little school girls dancing with the queen;

Seventeen little school girls driving a bullock team;

Sixteen little school girls creeping out unseen;

Fifteen little school girls hopping on the green;

Fourteen little schoolgirls floating down a stream;

Thirteen little school girls leaping out to delve;

Twelve little school girls racing out for leaven;

Eleven little school girls dodging a lion when—

Ten little school girls, all skipping in a line;

Nine little school girls swinging on a gate;

Eight little school girls, trying to fly to heaven;

Seven little school girls tripping out for sticks;

Six little school girls, going for a dive;

Five little school girls, sailing to explore;

Four little school girls steaming on the sea;

Three little school girls, riding on a moo;

Two little school girls, sliding about for fun;

One little school girl, the nicest, last and best, |

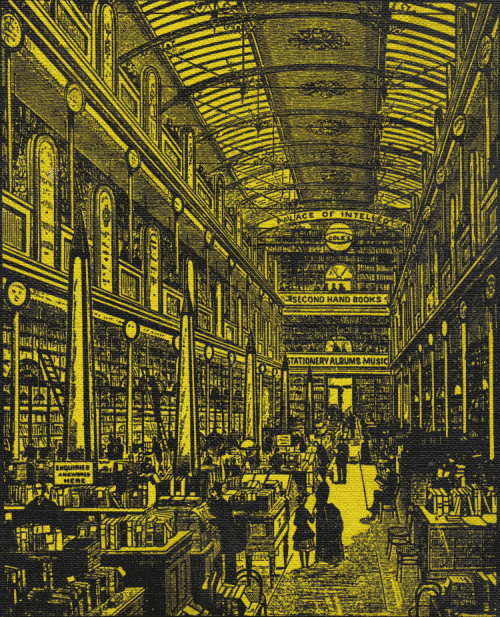

| The following is the way that each girl went into Cole's Book Arcade: |

|

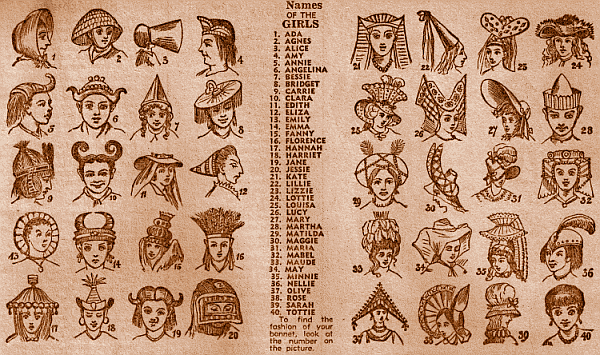

Ada ran into it. Agnes ran into it. Alice ran into it. Amy ran into it. Annie ran into it. Angelina ran into it. Bessie ran into it. Bridget ran into it. Carrie ran into it. Clara ran into it. Edith swam into it. Eliza swam into it. Emily swam into it. Emma swam into it. Fanny swam into it. Florence swam into it. Hannah swam into it. Harriet swam into it. Jane swam into it. Jessie swam into it. Kate jumped into it. Lillie skated into it. Lizzie danced into it. Lottie drove into it. Louisa crept into it. Lucy hopped into it. Mary floated into it. Martha leaped into it. Matilda raced into it. Maggie dodged into it. Maria skipped into it. Mabel swung into it. Maude flew into it. May tripped into it. Minnie dived into it. Nellie sailed into it. Olive Steamed into it. Rose rode into it. Sarah slid into it. Tottie walked into it. |

|

N.B.—Any little girl is invited to walk, run, jump, dance, skip,

hop, swim, fly, or come into Cole's Book Arcade in any way she

chooses, the same as the Forty Little School Girls.

|

|

Once there was a funny old monkey—and this old monkey had six young monkeys. There was one white monkey, and one black monkey, and one yellow monkey, and one red monkey, and one blue monkey, and one green monkey; and the white monkey's name was Linda, and the black monkey's name was Eddie, and the yellow monkey's name was Vally, and the red monkey's name was Ruby, and the blue monkey's name was Pearl, and the green Monkey's name was Ivy Diamond. And the white monkey liked apples, and the black monkey liked grapes, and the yellow monkey liked cherries, and the red monkey liked strawberries, and the blue monkey liked oranges, and the green monkey liked nuts, and that's all about these FUNNY MONKEYS. The names of any children can be told in this story instead of Linda, Eddie, Vally, Ruby, Pearl, and Diamond.

|

Page 22—Girl Land

|

There was a girl, named tanglepate,

She cried and made a dreadful fuss,

Her hair stood out around her head

It caught on buttons, hooks, and boughs

And so she fell asleep one day

|

|

I know a very careless girl,

Her skirts she catches on a nail,

'Tis her delight to tear and rend,

|

|

The naughty girl

She pinches the cat,

She worries poor grandma,

At school she forgets

At table she's careless,

|

|

Mopy Maria

She filled the room

She moped and pined

It wasn't her style

If the children came

Her face grew thin;

The winds were high,

|

|

Naughty May will not obey,

If you say do this, or that,

O she is a naughty child!

Some fine day, I don't know when—

Pigs are stubborn things indeed,

And pig-headed folks are they

|

|

Oh! Mary, my mary,

I thought you were pleas'd.

Her bonnet of straw

Suppose (you're my Dolly,

But Dolly's mere wood,

'Tis not for the Dolly

|

|

When I was living down in Wales,

The more she bit the more they bled,

See, here she is: she sadly stands

Her father said, "You naughty thing,

|

|

When little Lizzie came across

She chased the dog, she chased the cat,

She poked the turtles and the frogs

One day she chanced to find a hive

And so she did. As soon as she

|

Page 23—Girl Land

|

"Dear me! what signifies a pin,

So onward tripped the little maid,

Next day a party was to ride

In vain her eager eyes she brings

At last, as hunting on the floor,

There's hardly anything so small,

Ann Taylor

|

|

Oh! she was such a stupid Jane,

If she was set to do a task,

If on an errand told to go,

She did not care for books or toys,

Brought to the parlour nicely drest

Oh! she was such a stupid Jane,

|

|

The awfullest times that ever could be

|

|

Polly was a little girl,

Other little girls and boys

There they'd romp, and have great fun,

What had any one done?

Why are you so cross and glum

Polly loves to have her way;

Such a funny under-lip!

In the house or out-of-doors,

Once, when in the garden she

Then she danced, and then she screamed;

Oh, it swelled, and swelled, and swelled,

Many days she kept her bed;

For the buzzing busy-bee

|

|

Oh, here's a sad picture!

'Tis Emily's portrait:

Her mother implores her,

Her trimmings are torn;

Stockings down, buttons missing;

Her mother does nothing

"All, all is in vain.

A terrible thing

This girl ran quite wild;

A man, who was passing,

She is still standing there;

"Look at this dreadful thing!

|

Page 24—Girl Land

|

Maiden! with the meek, brown eyes,

Thou, whose locks outshine the sun,

Standing, with reluctant feet,

Gazing, with a timid glance,

Deep and still, that gliding stream

Then why pause with indecision,

Seest thou shadows sailing by,

Hearest thou voices on the shore,

O, thou child of many prayers!

Like the swell of some sweet tune,

Childhood is the bough where slumber'd

Gather, then each flower that grows,

Bear a lily in thy hand;

Bear, through sorrow, wrong, and ruth,

Oh! that dew, like balm, shall steal

And that smile, like sunshine, dart

Longfellow

|

|

The girls that are wanted are good girls—

The girls that are fair on the hearthstone,

The girls that are wanted are girls of sense,

The girls that are wanted are girls with hearts,

|

|

Francis, is "unrestrained and free;"

|

|

There's something in the name of Kate

There's deli-Kate, a modest dame,

Communi-Kate's intelligent,

There's intri-Kate, she's so obscure

Prevari-Kate's a surly maid,

There's alter-Kate, a perfect pest;

Then dislo-Kate, is quite a fret,

Equivo-Kate no one will woo—

There's vindi-Kate, she's good and true,

There's rusti-Kate, a country lass,

Of all the maidens you can find,

|

Page 25—Girl Land

|

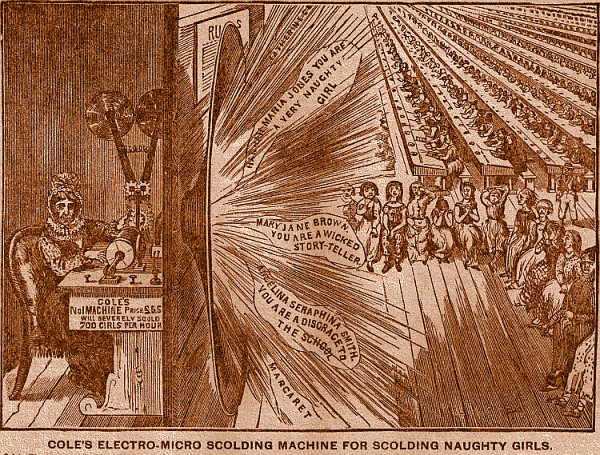

Cole's Electro-micro Scolding Machine is a combination of three instruments, the Phonograph, the Microphone, and the Wonderphone. The Phonograph is an instrument that will preserve words for any length of time. Any person can speak, sing, whistle, or scold into a Phonograph, and months or years afterwards by simply turning a handle the same sounds can be reproduced a dozen, a hundred, or a thousand times in the exact voice of the person who spoke them in; so that if a man or a woman, who is a great scold, speak some good, loud, severe scolding into a Phonograph, the mildest teacher can then scold her pupils, or the kindest mother her children, just by turning the handle. The Microphone is an instrument that magnifies sound in the same way as a microscope magnifies objects; a very powerful microphone magnifies the sound of a fly walking into a loud tramping footstep, the tick of a watch into a deafening clatter, and a whisper into a loud shout. Take a Microphone, then properly affix it to the Phonograph described above, and you have a good Scolding Machine; turn the handle, and as the Phonograph gives out the scoldings, the microphone part magnifies them so loudly that they are heard for a considerable distance. The Wonderphone (Cole's own secret) is another remarkable instrument; it will cause sound to travel very distinctly, but frightfully and equally loud, for forty miles in all directions; by attaching this powerful instrument to the combination of the other two, Cole's Electro-micro Scolding Machine is formed—and which is the first Scolding Machine ever invented. If the machine is already charged by having had some scolding spoken, or even whispered into it, give the handle a turn, and forty miles to the east, forty miles to the west, forty to the north, forty to the south, forty up in the sky, and down in the mines forty miles deep, in fact forty miles in every direction, everybody can clearly hear every word being said to the girl being scolded. Suppose for instance, Hannah Maria Smith had done something wrong in school, the schoolmistress could give the handle of the machine a turn, and it would scold her so loudly that her mother, and father, and brothers, and sisters, and uncles, and aunts, and friends, and those she didn't like would all hear her scolded. The machine can be charged on the instant by anyone scolding into it. In fact the whole value of Cole's Scolding Machine lies in its power to repeat out exceedingly loud whatever is spoken into it. If the schoolmistress chooses she can put the scolding into verse, so that all who hear it in the forty miles around, can more easily remember it. The machine that I have before me now, was charged this morning for an aristocratic school and speaks as follows:—Silence!! Attention!!! |

|

Ada Alice Arabella Angelina Andal, Why do you talk for ever, such a tittle-tattling scandal? Betsy Bertha Bridget Belinda Bowing, Will you be quiet and go on with your sewing? Cora Caroline Christina Clarinda Clare, Now do look in the glass at your untidy hair. Dorah Dinah Dorothy Dorinda Dresson, You really must get on with your short drawing lesson. Edith Ellen Evelina Elizabeth Eadle, This makes this day your nineteenth broken needle. Fanny Florence Frederica Florinda Flynn, How cruel of you to prick Jane with a pin. Grace Gertrude Genevieve Georgina Grimble, You careless girl to lose your silver thimble. Hilda Hanna Harriet Henrietta Hawker, You really are a most inveterate talker. Ida Izod Irene Isabella Inching, You spiteful—stop that scratching and pinching. Jane Julia Josephine Jemima Jesson, Sit down at once and learn your music lesson. Kate Kester Katrina Kathleen Kent, You're vulgar, saucy, rude and insolent. Lizzie Letitia Lucretia Lorinda Loeries, You're the champion of the world for telling stories. Maud Mary Martha Matilda Moyes, Sends letters to, and flirts with, naughty boys. Nancy Nelly Ninette Naomi Nations, Shame of you to talk 'gainst other girls' relations. Olive Osberta Orphelia Octavia O'Dyke, Your conduct is outrageous and unladylike. Polly Patience Prudence Paulina Pitt, You really are our champion tell-tale-tit. Quilla Quintina Quinburga Quendrida Quirk, How very, very, dirty you have made your fancy-work. Rose Ruth Rachel Rebecca Ritting, Now stop that crying and get on with your knitting. Sarah Sophia Selina Susannah Stacies, Don't spoil your face by making those grimaces. Tilda Theresa Tabitha Theodora Tapping, You'd gain the prize if one was given for slapping. Una Ursula Urica Urania Urls, You'd gain the prize for teasing little girls. Venus Violet Victoria Veronica Vo-shi, Just learn your task and put away that crochet. Wilmett Walberg Winefride Wilhelmina Wriggling, Now once for all do stop that stupid giggling. Xenodice Xanthippe Xanthisa Xenophona X-cess, You think and talk of nothing else but dress! dress! Yana Yulga Yapeena Yestina Young, Will you behave yourself and just draw in your tongue. And lastly and worst of all, you, Zoe Zora Zillah Zenobia Zeen, How dare you! how dare you!! yes, how dare you!!! Sneer at the boy's new whipping Machine.

|

|

If a schoolmistress chooses to live a hundred or a thousand miles away from her school, she can use the Scolding Machine by means of a Telephone attached thereto. One great advantage of the Electro-micro Scolding Machine is, that after it has been in use a short time the girls will all have been shamed into good behaviour; but the Machine will not become useless, as it can, without a farthing outlay, be turned into a Praising Machine, for it can be made to praise in a gentle voice as well as scold in a harsh one. In fact, as said above it will repeat in exact tones, anything that is recited, preached, sung, whistled, whispered, shouted, scolded or praised into it—and any of which will be heard for forty miles around. Cole can supply Scolding Machines from £5 to £50. A very good one (The Excelsior), price £10, can be charged in one minute, and set going like a musical box, and will sing, whistle, recite, preach, or scold away for a full hour without stopping. Cole would particularly recommend this one to the ladies, it would make a fine ornament for their own table. Final Notice Extraordinary—If the champion male scold of the world, and the champion female scold of the world, will call on Professor Cole, at the Book Arcade, Melbourne, he will give them both good wages, and find them constant employment at charging Scolding Machines. If any wife has got the champion male scold for a husband, she will please to let me know. If any husband has got the champion female scold for a wife, he will please to let me know—£10 bonus for information in each case.

E.W. Cole

|

Page 26—Good Girls

|

An orphan child was Jenny Lee;

In winter time, she often rose

And she would always say to Jane,

"Keep baby quiet in his bed,

"And don't let little Christopher,

"And mind about the fire, child,

"Good-by my precious comforter,

Then Jenny she was quite as proud

She did not stop to waste her time,

If down upon the cottage floor

And when the little babe was cross,

But when they both were safe in bed,

Then open flew the cottage door,

|

|

"Mother has sent me to the well,

"Some afternoon I'll come with you,

"She says, that I am nearly eight,

"So Johnny, do not ask to-day—

|

|

Oft I had heard of Lucy Gray;

No mate, no comrade Lucy knew;

You yet may spy the fawn at play,

"To-night will be a stormy night—

"That, father, will I gladly do!

At this the father raised his book

Not blither is the mountain roe;

The storm came on before it's time;

The wretched parents all that night

At day-break on a hill they stood

And, turning homeward, now they cried

Then downwards from the steep hill's edge

And then an open field they crossed—

They followed from the snowy bank

Yet some maintain that to this day

O'er rough and smooth she trips along,

|

|

Mary had a little lamb,

He followed her to school one day—

The teacher therefore turned him out;

At once he ran to her, and laid

"What makes the lamb love Mary so?"

|

Page 27—Girl Land

|

I met a little cottage girl;

She had a rustic, woodland air,

"Sisters and brothers, little maid,

"And where are they? I pray you tell."

"Two of us in the churchyard lie—

"You say that two at Conway dwell,

Then did the little maid reply,

"You run about, my little maid,

"Their graves are green, they may be seen,"

"My stockings there I often knit,

"And often after sunset, sir,

"The first that died was little Jane;

"So in the churchyard she was laid;

"And when the ground was white with snow,

"How many are you then? said I,

"But they are dead; those two are dead;

|

|

Young Lucy Payne lives on the Village Green;

She plies her needles, and she plies them well,

I pass'd one morning by their cottage door;

Hanger had tamed the little wilding thing,

It was her breakfast—all the darling

had;

|

|

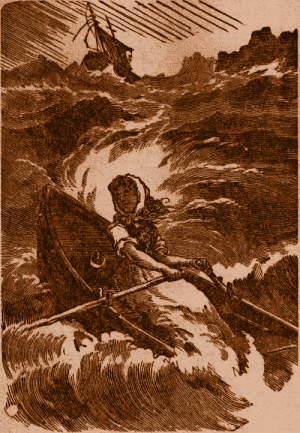

"Over the wave, the stormy wave,

"Out with the boat, the gallant boat;

"I have no fear, no maiden fear;

"The wreck we near, the wreck we near,

Hail to the maid, the fearless maid,

|

|

Who is it each day in the week may be seen,

Go visit her cottage, though humble and poor.

|

|

"I will be good, dear mother,"

Oh, many, many, bitter tears

|

|

I have a little sister,

|

Page 28—Ruby Cole And Her Clever Frog

|

She danced like a Fairy,

Oh yes! Oh yes! She did! She Did!

She mooed like a Bullock,

She brayed like a Donkey,

She munched like a Rabbit,

She talked like a Parrot,

She climbed like a Squirrel,

She crept like a Tortoise,

She roared like a Lion,

She croaked like a Raven,

She grinned like a Monkey,

|

|

Our dear little daughter once went to a children's ball dressed as a

fairy. She was proud of being a fairy, and looked so nice that I put

together the above nursery doggerel to please her, and in honour of

the event, little thinking that she would soon leave this world. It

might be considered better by some to remove this page, but as

children like it I venture to let it stand with this explanation.

E. W. C.

|

| Sacred to the Memory of our dear LITTLE RUBY, who departed this life March 27th, 1890, aged 8 years. She was intelligent, industrious, affectionate and sociable, and is deeply regretted by all who knew her. |

|

There is no flock, however watched and tended But one dead lamb is there! There is no fireside, howsoever defended But has one vacant chair!

There is no death! what seems so is transition

She is not dead—the child of our

affection—

|

Page 29—Vally Cole And His Clever Dog

|

Our Vally had a Clever Dog, whose name was EBENEZER. Sometimes this dog was very good, At other times a TEASER.

|

|

One day they went to take a bath, And both sat on a rail; Our Vally hung his legs right down, The dog hung down his tail.

|

|

This funny Dog one Christmas day, Directly after dinner, Just lean'd his sleepy head against Old Tom, our snoozing sinner.

|

Page 30—Boy's Stories

|

Tommy Trot, a man of law, Sold his bed and lay upon straw; Sold the straw and slept on grass, To buy his wife a looking-glass.

Little Jack Jingle,

I'll tell you a story

Poor old Robinson Crusoe!

"John, come sell thy fiddle,

Jacky, come give me thy fiddle

Jack was a fisherman

The Queen of Hearts,

The King of Hearts

Charley Wag

|

|

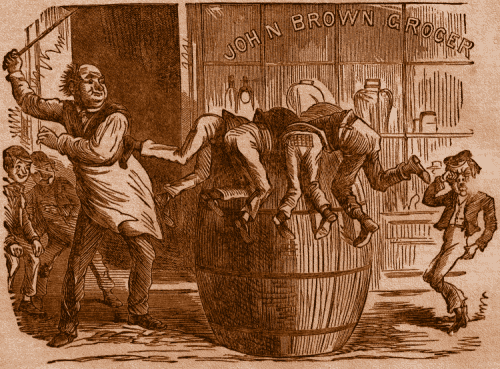

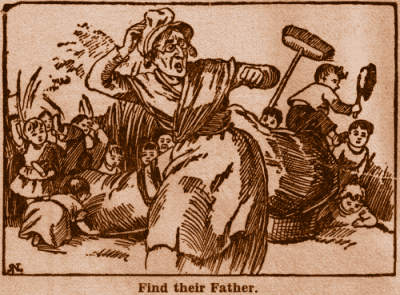

Tom, Tom, the piper's son,

Tom, he was a piper's son:

Now Tom with his pipe made such a noise,

|

|

Tom with his pipe did play with such skill, That those who heard him could never keep still: Whenever they heard they began for to dance, Even the pigs on their hind legs would after him prance.

As Dolly was milking her cow one day,

He met old Dame Trot with a basket of eggs,

He saw a cross fellow beating an ass,

Tom met the parson on his way,

The mayor then said he would not fail

'Twas quite a treat to see the rout,

The Policeman Grab, who held him fast,

Taffy was a Welshman, Taffy was a thief,

Old King Cole

Peter White will ne'er go right;

|

Page 31—Boy Land

|

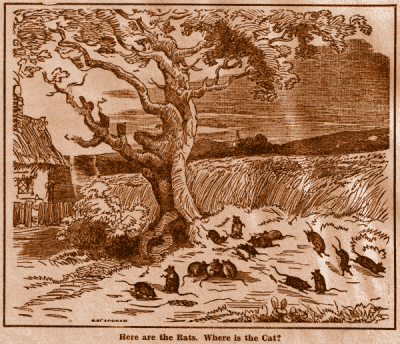

This is the house that Jack built.

This is the malt

This is the rat,

This is the cat,

This is the dog,

This is the cow with the crumpled horn,

This is the maiden all forlorn,

This is the man all tattered and torn,

This is the priest all shaven and shorn,

This is the cock that crowed in the morn,

This is the farmer sowing his corn,

|

|

Simple Simon met a pieman

Says the pieman to Simple Simon,

Simple Simon went a-fishing

Simple Simon went to look

He went to catch a dicky bird,

Then Simple Simon went-a-hunting,

Simon made a great snowball,

Simple Simon went a-skating

And Simon he would honey eat

|

|

Ten little Niggers going out to dine,

Nine little Niggers crying at his fate,

Eight little Niggers to travelling were given.

Seven little Niggers playing at their tricks,

Six little Niggers playing with a hive,

Five little Niggers went in for law,

Four little Niggers going out to sea,

Three little Niggers walking in the Zoo,

Two little Niggers sitting in the sun,

One little Nigger living all alone,

|

Page 32—Boy Land

|

Once upon a time there lived in Cornwall, England, a lad whose name was Jack, and who was very brave and knowing. At the same time there was a great Giant, twenty feet high and nine feet round, who lived in a cave, on an island near Jack's house. The Giant used to wade to the mainland and steal things to live upon, carrying five or six bullocks at once, and stringing sheep, pigs, and geese around his waist-band; and all the people ran away from him in fear, whenever they saw him coming. Jack determined to destroy this Giant; so he got a pickaxe and shovel, and started in his boat on a dark evening; by the morning he had dug a pit deep and broad, then covering it with sticks and strewing a little mould over, to make it look like plain ground, he blew his horn so loudly that the Giant awoke, and came roaring towards Jack, calling him a villain for disturbing his rest, and declaring he would eat him for breakfast. He had scarcely said this when he fell into the pit. "Oh! Mr. Giant," says Jack, "where are you now? You shall have this for your breakfast." So saying, he struck him on the head so terrible blow with his pickaxe that the Giant fell dead to the bottom. Just at this moment, the Giant's brother ran out roaring vengeance against Jack; but he jumped into his boat and pulled to the opposite shore, with the Giant after him, who caught poor Jack, just as he was landing, tied him down in his boat, and went in search of his provisions. During his absence, Jack contrived to cut a large hole in the bottom of the boat, and placed therein a piece of canvas. After having stolen some oxen, the Giant returned and pushed off the boat, when, having got fairly out to sea, Jack pulled the canvas from the hole, which caused the boat to fill and quickly capsize. The Giant roared and bellowed as he struggled in the water, but was very soon exhausted and drowned, while Jack dexterously swam ashore. One day after this, Jack was sitting by a well fast asleep. A Giant named Blundebore, coming for water, at once saw and caught hold of him, and carried him to his castle. Jack was much frightened at seeing the heaps of bodies and bones strewed about. The Giant then confined him in an upper room over the entrance, and went for another Giant to breakfast off poor Jack. On viewing the room, he saw some strong ropes, and making a noose at one end, he put the other through a pulley which chanced to be over the window, and when the Giants were unfastening the gate he threw the noose over both their heads, and pulling it immediately, he contrived to choke them both. Then releasing three ladies who were confined in the castle, he departed well pleased. About five or six months after, Jack was journeying through Wales, when, losing his way, he could find no place of entertainment, and was about giving up all hopes of obtaining shelter during the night when he came to a gate, and, on knocking, to his utter astonishment it was opened by a Giant, who did not seem so fierce as the others. Jack told him his distress, when the Giant invited him in, and, after giving him a hearty supper, showed him to bed. Jack had scarcely got into bed when he heard the Giant muttering to himself: |

|

"Though you lodge with me this night, You shall not see the morning light; My club shall dash your brains out quite." |

|

"Oh, Mr. Giant, is that your game?" said Jack to himself; "then I

shall try and be even with you." So he jumped out of bed and put a

large lump of wood there instead. In the middle of the night the

Giant went into the room, and thinking it was Jack in the bed, he

belaboured the wood most unmercifully; he then left the room,

laughing to think how he had settled poor Jack. The following morning

Jack went boldly into the Giant's room to thank him for the night's

lodging. The Giant was startled at his appearance, and asked him how

he slept, or if anything had disturbed him in the night? "Oh, no,"

says Jack, "nothing worth speaking about: I believe that a rat gave

me a few slaps with his tail, but, being rather sleepy, I took no

notice of it." The Giant wondered how Jack survived the terrific

blows of his club, yet did not answer a word, but went and brought in

two monstrous bowls of hasty pudding, placed one before Jack, and

began eating the other himself. Determined to be revenged on the

Giant somehow, Jack unbuttoned his leather provision bag inside his

coat, and slyly filling it with hasty pudding, said, "I'll do what

you can't." So saying, he took up a large knife, and ripping up the

bag, let out the hasty pudding. The Giant, determined not to be

outdone, seized hold of the knife, and saying, "I can do that,"

instantly ripped up his belly, and fell down dead on the spot.

After this Jack fought and conquered many giants, married the king's daughter and lived happily.

|

|