Project Gutenberg's The History of Woman Suffrage, Volume IV, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The History of Woman Suffrage, Volume IV

Author: Various

Editor: Susan B. Anthony

Ida Husted Harper

Release Date: August 31, 2009 [EBook #29870]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HIST OF WOMAN SUFFRAGE, VOL 4 ***

Produced by Richard J. Shiffer and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible, including obsolete and variant spellings and other inconsistencies. Text that has been changed to correct an obvious error is noted at the end of this ebook.

Also, many occurrences of mismatched single and double quotes remain as they were in the original.

This book contains links to individual volumes of "History of Woman Suffrage" contained in the Project Gutenberg collection. Although we verify the correctness of these links at the time of posting, these links may not work, for various reasons, for various people, at various times.

* * * * Make me respect my material so much that I dare not slight my work. Help me to deal very honestly with words and with people, because they are both alive. Show me that, as in a river, so in writing, clearness is the best quality, and a little that is pure is worth more than much that is mixed. Teach me to see the local color without being blind to the inner light. Give me an ideal that will stand the strain of weaving into human stuff on the loom of the real. Keep me from caring more for books than for folks, for art than for life. Steady me to do my full stint of work as well as I can, and when that is done, stop me, pay me what wages thou wilt, and help me to say from a quiet heart a grateful Amen.

After the movement for woman suffrage, which commenced about the middle of the nineteenth century, had continued for twenty-five years, the feeling became strongly impressed upon its active promoters, Miss Susan B. Anthony and Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, that the records connected with it should be secured to posterity. With Miss Anthony, indeed, the idea had been ever present, and from the beginning she had carefully preserved as far as possible the letters, speeches and newspaper clippings, accounts of conventions and legislative and congressional reports. By 1876 they were convinced through various circumstances that the time had come for writing the history. So little did they foresee the magnitude which this labor would assume that they made a mutual agreement to accept no engagements for four months, expecting to finish it within that time, as they contemplated nothing more than a small volume, probably a pamphlet of a few hundred pages. Miss Anthony packed in trunks and boxes the accumulations of the years and shipped them to Mrs. Stanton's home in Tenafly, N. J., where the two women went cheerfully to work.

Mrs. Stanton was the matchless writer, Miss Anthony the collector of material, the searcher of statistics, the business manager, the keen critic, the detector of omissions, chronological flaws and discrepancies in statement such as are unavoidable even with the most careful historian. On many occasions they called to their aid for historical facts Mrs. Matilda Joslyn Gage, one of the most logical, scientific and fearless writers of her day. To Mrs. Gage Vol. I of the History of Woman Suffrage is wholly indebted for the first two chapters—Preceding Causes and Woman in Newspapers, and for the last chapter—Woman, Church and State, which she later amplified in a book; and Vol. II for the first chapter—Woman's Patriotism in the Civil War.

When the allotted time had expired the work had far exceeded[Pg vi] its original limits and yet seemed hardly begun. Its authors were amazed at the amount of history which already had been made and still more deeply impressed with the desirability of preserving the story of the early struggle, but both were in the regular employ of lecture bureaus and henceforth could give only vacations to the task. They were entirely without the assistance of stenographers and typewriters, who at the present day relieve brain workers of so large a part of the physical strain. A labor which was to consume four months eventually extended through ten years and was not completed until the closing days of 1885. The pamphlet of a few hundred pages had expanded into three great volumes of 1,000 pages each, and enough material remained unused to fill another.[1]

It was almost wholly due to Miss Anthony's clear foresight and painstaking habits that the materials were gathered and preserved during all the years, and it was entirely owing to her unequaled determination and persistence that the History was written. The demand for Mrs. Stanton on the platform and the cares of a large family made this vast amount of writing a most heroic effort, and one which doubtless she would have been tempted to evade had it not been for the relentless mentor at her side, helping to bear her burdens and overcome the obstacles, and continually pointing out the necessity that the history of this movement for the emancipation of women should be recorded, in justice to those who carried it forward and as an inspiration to the workers of the future. And so together, for a long decade, these two great souls toiled in the solitude of home just as together they fought in the open field, not for personal gain or glory, but for the sake of a cause to which they had consecrated their lives. Had it not been for their patient and unselfish labor the story of the hard conditions under which the pioneers struggled to lift woman out of her subjection, the bitterness of the prejudice, the cruelty of the persecution, never would have been told. In all the years that have passed no one else has attempted[Pg vii] to tell it, and should any one desire to do so it is doubtful if, even at this early date, enough of the records could be found for the most superficial account. In not a library can the student who wishes to trace this movement to its beginning obtain the necessary data except in these three volumes, which will become still more valuable as the years go by and it nears success.

Miss Anthony began this work in 1876 without a dollar in hand for its publication. She never had the money in advance for any of her undertakings, but she went forward and accomplished them, and when the people saw that they were good they usually repaid the amount she had advanced from her own small store. In this case she resolved to use the whole of it and all she could earn in the future rather than not publish the History. Mrs. Elizabeth Thompson, of New York, a generous patron of good works, gave her the first $1,000 in 1880, but this did not cover the expenses that had been actually incurred thus far in its preparation. She was in nowise discouraged, however, but kept steadily on during every moment which could be spared by Mrs. Stanton and herself, absolutely confident that in some way the necessary funds would be obtained. Her strong faith was justified, for the first week of 1882 came a notice from Wendell Phillips that Mrs. Eliza Jackson Eddy, of Boston, had left her a large legacy to be used according to her own judgment "for the advancement of woman's cause." Litigation by an indirect heir deprived her of this money for over three years, but in April, 1885, she received $24,125.

The first volume of the History had been issued in May, 1881, and the second in April, 1882. In June, 1885, Mrs. Stanton and Miss Anthony set resolutely to work and labored without ceasing until the next November, when the third volume was sent to the publishers. With the bequest Miss Anthony paid the debts that had been incurred, replaced her own fund, of which every dollar had been used, and brought out this last volume. All were published at a time when paper and other materials were at a high price. The fine steel engravings alone cost $5,000. On account of the engagements of the editors it was necessary to employ proofreaders and indexers, and because of the many years over which the work had stretched an immense number of changes[Pg viii] had to be made in composition, so that a large part of the legacy was consumed.

The money which Miss Anthony now had enabled her to carry out her long-cherished project to put this History free of charge in the public libraries. It was thus placed in twelve hundred in the United States and Europe. Mrs. Stanton and Mrs. Gage, who had contributed their services without price, naturally felt that it should be sold instead of given away, and in order to have a perfectly free hand she purchased their rights. In addition to the libraries, she has given it to hundreds of schools and to countless individuals, writers, speakers, etc., whom she thought it would enable to do better work for the franchise. For seventeen years she has paid storage on the volumes and the stereotype plates. During this time there has been some demand for the books from those who were able and willing to pay, but much the largest part of the labor and money expended were a direct donation to the cause of woman suffrage.

From the time the last volume was finished it was Miss Anthony's intention, if she should live twenty years longer, to issue a fourth containing the history which would be made during that period, and for this purpose she still preserved the records. As the century drew near a close, bringing with it the end of her four-score years, the desire grew still stronger to put into permanent shape the continued story of a contest which already had extended far beyond the extreme limits imagined when she dedicated to it the full power of her young womanhood with its wealth of dauntless courage and unfailing hope. She resigned the presidency of the National Association in February, 1900, which marked her eightieth birthday, in order that she might carry out this project and one or two others of especial importance. Among her birthday gifts she received $1,000 from friends in all parts of the country, and this sum she resolved to apply to the contemplated volume. One of the other objects which she had in view was the collecting of a large fund to be invested and the income used in work for the enfranchisement of women. Already about $3,000 had been subscribed.

By the time the first half year had passed, nature exacted tribute for six decades of unceasing and unparalleled toil, and[Pg ix] it became evident that the idea of gathering a reserve fund would have to be abandoned. The donors of the $3,000 were consulted and all gave cordial assent to have their portion applied to the publication of the fourth volume of the History. The largest amount, $1,000, had been contributed by Mrs. Pauline Agassiz Shaw, of Boston. Dr. Cordelia A. Greene, of Castile, N. Y., had given $500 and Mrs. Emma J. Bartol, of Philadelphia, $200. The other contributions ranged all the way down to a few dollars, which in many cases represented genuine sacrifice on the part of the givers. It is not practicable to publish the list of the women in full. They will be sufficiently rewarded in the consciousness of having helped to realize Miss Anthony's dream of finishing the story, to the end of her own part in it, of a great progressive movement in which they were her fellow-workers and loyal friends.

Mrs. Gage passed away in 1898. Although Mrs. Stanton is still living as this volume goes to the publishers in 1902, and evinces her mental vigor at the age of eighty-seven in frequent magazine and newspaper articles, she could not be called upon for this heavy and exacting task. It seemed to Miss Anthony that the one who had recently completed her Biography, in its preparation arranging and classifying her papers of the past sixty years, and who necessarily had made a thorough study of the suffrage movement from its beginning, should share with her this arduous undertaking. The invitation was accepted with much reluctance because of a full knowledge of the great labor and responsibility involved. It must be confessed that even a strong sense of obligation to further the cause of woman's enfranchisement would not have been a sufficient incentive, but personal devotion to a beloved and honored leader outweighed all selfish considerations. It is to Miss Anthony, however, that the world is indebted for this as well as the other volumes. It was she who conceived the idea; through her came the money for its publication; for several years her own home has been given up to the mass of material, the typewriters, the coming and going of countless packages, the indescribable annoyances and burdens connected with a matter of this kind. In addition she has borne from her private means a considerable portion of the expenses,[Pg x] and has endured the physical weariness and mental anxiety at a time when she has earned the right to complete rest and freedom from care. There is not a chapter which has not had the inestimable benefit of her acute criticism and matured judgment.

The peculiar difficulties of historical work can be understood only by those who have experienced them. General information is the easiest of all things to obtain—exact information the hardest, and a history that is not accurate has no practical utility. If a reader discover one mistake it vitiates the whole book. Every historian knows how common it is to find several totally different statements of the same occurrence, each apparently as authentic as the others. He also knows the eel-like elusiveness of dates and the flat contradictions of statistics which seem to disprove absolutely the adage that "figures do not lie." He has suffered the nightmare of wrestling with proper names; and if he is conscientious he has agonized over the attempt to do exact justice to the actors in the drama which he is depicting and yet not detract from its value by loading it with trivial details, of vital moment to those who were concerned in them but of no importance to future readers. All of these embarrassments are intensified in a history of a movement for many years unnoticed or greatly misrepresented in the public press, and its records usually not considered of sufficient value to be officially preserved. None, however, has required such supreme courage and faithfulness from its adherents and this fact makes all the more obligatory the preserving of their names and deeds.

To collect the needful information from fifty States and Territories and arrange it for publication has required the careful and constant work of over two years. It has been necessary many times to appeal to public officials, who have been most obliging, but the main dependence has been on the women of various localities who are connected with the suffrage associations. These women have spent weeks of time and labor, writing letters, visiting libraries, examining records, and often leaving their homes and going to the State capital to search the archives. All this has been done without financial compensation, and it is largely through their assistance that the editors have been able to prepare this volume. To give an idea of the exacting work[Pg xi] required it may be stated that to obtain authentic data on one particular point the writer of the Kansas chapter sent 198 letters to 178 city clerks. The meager record of Florida necessitated about thirty letters of inquiry. Several thousand were sent out by the editors of the History, while the number exchanged within the various States is beyond computation.

The demand is widespread that the information which this book contains should be put into accessible shape. Miss Anthony herself and the suffrage headquarters in New York are flooded with inquiries for statistics as to the gains which have been made, the laws for women, the present status of the question and arguments that can be used in the debates which are now of frequent occurrence in Legislatures, universities, schools and clubs in all parts of the country. Practically everything that can be desired on these points will be found herein. The first twenty-two chapters contain the whole argument in favor of granting the franchise to women, as every phase of the question is touched and every objection considered by the ablest of speakers. It has been a special object to present here in compact form the reasons on which is based the claim for woman suffrage. In Chapter XXIV and those following are included the laws pertaining to women, their educational and industrial opportunities, the amount of suffrage they possess, the offices they may fill, legislative action on matters concerning them, and the part which the suffrage associations have had in bringing about present conditions. There are also chapters on the progress made in foreign countries and on the organized work of women in other lines besides that of the franchise. All the care possible has been taken to make each chapter accurate and complete.

Beginning with 1884, where Vol. III closes, the present volume ends with the century. This is not a book which must necessarily wait upon posterity for its readers, but it is filled with live, up-to-date information. Its editors take the greatest pleasure in presenting it to the young, active, progressive men and women of the present day, who, without doubt, will bring to a successful end the long and difficult contest to secure that equality of rights which belongs alike to all the citizens of this largest of republics and greatest of nations.

[1] The reader can not fail to be interested in the personal story of the writing of these books as related in the Reminiscences of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony—the many journeys made by the big boxes of documents from the home of one to that of the other; the complications with those who were gathering data in their respective localities; the trials with publishers; the delays, disappointments and vexations, all interspersed and brightened with many humorous features.

It has been frequently said that the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage, which bring the record to twenty years ago, represent the seed-sowing time of the movement. They do far more than this, for seeds sown in the early days which they describe would have fallen upon ground so stony that if they had sprung up they would soon have withered away. The pioneers in the work for the redemption of women found an unbroken field, not fallow from lying idle, but arid and barren, filled with the unyielding rocks of prejudice and choked with the thorns of conservatism. It required many years of labor as hard as that endured by the forefathers in wresting their lands from undisturbed nature, before the ground was even broken to receive the seed. Then followed the long period of persistent tilling and sowing which brought no reaping until the last quarter of the century, when the scanty harvest began to be gathered. The yield has seemed small indeed at the end of each twelvemonth and it is only when viewed in the aggregate that its size can be appreciated. The condition of woman to-day compared with that of last year seems unchanged, but contrasted with that of fifty years ago it presents as great a revolution as the world has ever witnessed in this length of time.

If the first organized demand for the rights of woman—made at the memorable convention of Seneca Falls, N. Y., in 1848—had omitted the one for the franchise, those who made it would have lived to see all granted. It asked for woman the right to have personal freedom, to acquire an education, to earn a living, to claim her wages, to own property, to make contracts, to bring suit, to testify in court, to obtain a divorce for just cause, to possess her children, to claim a fair share of the accumulations during marriage. An examination of Chap. XXIV and the following chapters in this volume will show that in many of the States[Pg xiv] all these privileges are now accorded, and in not one are all refused, but when this declaration was framed all were denied by every State. For the past half century there has been a steady advance in the direction of equal rights for women. In many instances these have been granted in response to the direct efforts of women themselves; in others without exertion on their part but through the example of neighboring States and as a result of the general trend toward a long-delayed justice. Enough has been accomplished in all of the above lines to make it absolutely certain that within a few years women everywhere in the United States will enjoy entire equality of legal, civil and social rights.

Behind all of these has been the persistent demand for political rights, and the question naturally arises, "Why do these continue to be denied? Educated, property-owning, self-reliant and public-spirited, why are women still refused a voice in the Government? Citizens in the fullest sense of the word, why are they deprived of the suffrage in a country whose institutions rest upon individual representation?"

There are many reasons, but the first and by far the most important is the fact that this right, and this alone of all that have had to be gained for woman, can be secured only through Constitutional Law. All others have rested upon statute law, or upon the will of a board of trustees, or of a few individuals, or have needed no official or formal sanction. The suffrage alone must be had through a change of the constitution of the State and this can be obtained only by consent of the majority of the voters. Therefore this most valuable of all rights—the one which if possessed by women at the beginning would have brought all the others without a struggle—is placed absolutely in the hands of men to be granted or withheld at will from women. It is an unjust condition which does not exist even in a monarchy of the Old World, and it makes of the United States instead of a true republic an oligarchy in which one-half of the citizens have entire control of the other half. There is not another country having an elected representative body, where this body itself may not extend the suffrage. While the writing of this volume has been in progress the Parliament of Australia by a single Act has fully enfranchised the 800,000 women of that commonwealth. The Parliament of Great Britain has conferred on women every[Pg xv] form of suffrage except that for its own members, and there is a favorable prospect of this being granted long before the women of the United States have a similar privilege.

Not another nation is hampered by a written Federal Constitution which it is almost impossible to change, and by forty-five written State constitutions none of which can be altered in the smallest particular except by consent of the majority of the voters. Every one of these constitutions was framed by a convention which no woman had a voice in selecting and of which no woman was a member. With the sole exception of Wyoming, not one woman in the forty-five States was permitted a vote on the constitution, and every one except Wyoming and Utah confined its elective franchise strictly to "male" citizens.

Thus, wherever woman turns in this boasted republic, from ocean to ocean, from lakes to gulf, seeking the citizen's right of self-representation, she is met by a dead wall of constitutional prohibition. It has been held in some of the States that this applies only to State and county suffrage and that the Legislature has power to grant the Municipal Franchise to women. Kansas is the only one, however, which has given such a vote. A bill for this purpose passed the Legislature of Michigan, after years of effort on the part of women, and was at once declared unconstitutional by its Supreme Court. Similar bills have been defeated in many Legislatures on the ground of unconstitutionality. It is claimed generally that they may bestow School Suffrage and this has been granted in over half the States, but frequently it is vetoed by the Governor as unconstitutional, as has been done several times in California. In New York, after four Acts of the Legislature attempting to give School Suffrage to all women, three decisions of the highest courts confined it simply to those of villages and country districts where questions are decided at "school meetings." Eminent lawyers hold that even this is "unconstitutional." (See chapter on New York.) The Legislature and courts of Wisconsin have been trying since 1885 to give complete School Suffrage to women and yet they are enabled to exercise it this year (1902) for the first time. (See chapter on Wisconsin.) Some State constitutions provide, as in Rhode Island, that no form even of School Suffrage can be conferred[Pg xvi] on women until it has been submitted as an amendment and sanctioned by a majority of the voters.

The constitutions of a number of States declare that it shall not be sufficient to carry an amendment for it to receive a majority of the votes cast upon it, but it must have a majority of the largest vote cast at the election. Not one State where this in the case ever has been able to secure an amendment for any purpose whatever. Minnesota submitted this question itself to the electors in 1898 in the form of an amendment and it was carried, receiving a total of 102,641, yet the largest number of votes cast at that election was 251,250, so if its own provisions had been required it would have been lost. Nebraska is about to make an effort to get rid of such a provision, but, as this can be done only by another amendment to the constitution, the dilemma is presented of the improbability of securing a vote for it which shall be equal to the majority of the highest number cast at the general election. Since it is impossible to get such a vote even on questions to which there is no special objection, it is clearly evident that an amendment enfranchising women, to which there is a large and strong opposition, would have no chance whatever in States making the above requirement.

It then remains to consider the situation in those States where only a majority of the votes cast upon the amendment itself is required. One or two instances will show the stubborn objection which exists among the masses of men to the very idea of woman suffrage. In 1887 the Legislature of New Jersey passed a law granting School Suffrage to women in villages and country districts. After they had exercised it until 1894 the Supreme Court declared it to be unconstitutional, as "the Legislature can not enlarge or diminish the class of voters." The women decided it was worth while to preserve even this scrap of suffrage, so they made a vigorous effort to secure from the Legislature the submission of an amendment which should give it to them constitutionally. The resolution for this had to pass two successive Legislatures, and it happened in this case that by a technicality three were necessary, but with hard work and a petition signed by 7,000 the amendment was finally submitted in 1897. The unvarying testimony of the school authorities was that the women had used their vote wisely and to the great advantage of[Pg xvii] the schools during the seven years; there was no organized opposition from the class who might object to the Full Suffrage for women lest their business should be injured, or that other class who might fear their personal liberty would be curtailed; yet the proposition to restore to women in the villages and country districts the right simply to vote for school trustees was defeated by 75,170 noes, 65,029 ayes—over 10,000 majority.

South Dakota as a Territory permitted women to vote for all school officers. It entered the Union in 1889 with a clause in its constitution authorizing them to vote "at any election held solely for school purposes." They soon found that this did not include State and county superintendents, who are voted for at general elections, and that in order to get back their Territorial rights an amendment would have to be submitted to the electors. This was done by the Legislature of 1893. There had not been the slightest criticism of the way in which they had used their school suffrage during the past fourteen years, no class was antagonized, and yet this amendment was voted down by 22,682 noes, 17,010 ayes, an opposing majority of 5,672.

With these examples in two widely-separated parts of the country, the old and the new, representing not only crystallized prejudice in the one but inborn opposition in both to any step toward enfranchising women, and with this depending absolutely on the will of the voters, is it a matter of wonder that its progress has been so slow? If the question were submitted in any State to-day whether, for instance, all who did not pay taxes should be disfranchised, and only taxpayers were allowed to vote upon it, it would be carried by a large majority. If it were submitted whether all owning property above a certain amount should be disfranchised, and only those who owned less than this, or nothing, were allowed to vote, it would be carried unanimously. No class of men could get any electoral right whatever if it depended wholly on the consent of another class whose interests supposedly lay in withholding it. Political, not moral influence removed the property restrictions from the suffrage in order to build up a great party—the Democratic—which because of its enfranchisement of wage-earning men has received their support for eighty years. After the Civil War, although the Republican party was in absolute control, amendments to the State constitutions[Pg xviii] for striking out the word "white," in order to enfranchise colored men, were defeated in one after another of the Northern States, even in Kansas, the most radical of them all in its anti-slavery sentiment. It finally became so evident that this concession would not be granted by the voters that Congress was obliged to submit first one and then a second amendment to the Federal Constitution to secure it. But even then the ratification of the necessary three-fourths of the Legislatures could be obtained only because it was positively certain that through this action an immense addition would be made to the Republican electorate. Now after a lapse of thirty years this same party looks on unmoved at the violation of these amendments in every Southern State because it is believed that thus there can be, through white suffrage, the building up of the party in that section which the colored vote has not been able to accomplish.

The most superficial examination of the conditions which govern the franchise answers the question why, after fifty years of effort, so little progress has been made in obtaining it for women. Of late years every new or "third" party which is organized declares for woman suffrage. This is partly because such parties come into existence to carry out reforms in which they believe women can help, and partly because in their weak state they are ready to grasp at straws. While giving them full credit for such recognition, whatever may be its inspiring motive, it is clearly evident that the franchise must come to women through the dominant parties. If either of these could have had assurance of receiving the majority of the woman's vote it would have been obtained for her long ago without effort on her part, just as the workingman's and the colored man's were secured for them, but this has been impossible. Even in the four States where women now have the full suffrage neither party has been able to claim a distinct advantage from it. At the last Presidential election two of the four went Democratic and two Republican. In Colorado, where women owed their enfranchisement very largely to the Populists, that party was deposed from power at the first election where they voted and never has been reinstated. Although there was no justification for holding women responsible, they were so held, and the party consequently did not extend the franchise to women in other States where it[Pg xix] might have done so. Many consider that the principles of the Republican party in general would be more apt to commend themselves to women than those of the Democratic, but others believe that, so great is their antipathy to war and all the evils connected with it and the consequences following it, they would have opposed the party responsible for these during the past four years. It may be accepted, however, as the most probable view that women will divide on the main issues in much the same proportion as men. From this standpoint neither party will see any especial advantage in their enfranchisement, and both will look with disfavor upon adding to the immense number of voters who must now be reckoned with in every campaign an equally great number who are likely to require an entirely different management. There is a certain element in the leadership of all parties which is not especially objectionable to men, but would not be tolerated by women. Candidates who would be perfectly acceptable to men if they were sound on the political issues might be wholly repudiated by the women of their own party. If temperance and morality were made requisites many leaders and officials who now hold high position would be permanently retired. These are all reasons which appeal to politicians for deferring the day of woman suffrage as long as possible.

Each of the two dominant parties is largely controlled by what are known as the liquor interests. Their influence begins with the National Government, which receives from them billions of revenue; it extends to the States, to which they pay millions; to the cities, whose income they increase by hundreds of thousands; to the farmers, who find in breweries and distilleries the best market for their grain. There is no hamlet so small as not to be touched by their ramifications. No "trust" ever formed can compare with them in the power which they exercise. That their business shall not be interfered with they must possess a certain authority over Congress and Legislatures. They and the various institutions connected with them control millions of votes. They are among the largest contributors to political campaigns. There are few legislators who do not owe their election in a greater or less degree to the influence wielded by these liquor interests, which are positively, unanimously and unalterably opposed to woman suffrage. This can be gained only by the submission of[Pg xx] an amendment to the National or State constitutions, and for that women must go to the Congress or the Legislatures. What can they offer to offset the influences behind these bodies? They have no money to contribute for party purposes. They represent no constituency and can not pledge a single vote, a situation in which no other class is placed. They ask men to divide a power of which they now have a monopoly; to give up a sure thing for an uncertainty; to sacrifice every selfish interest—and all in the name of abstract justice, a word which has no place in politics. Was there ever apparently a more hopeless quest?

With the exception of the three amendments made necessary by the Civil War, the Federal Constitution has not been amended for ninety-eight years, and there is strong opposition to any changes in that instrument. If Congress would submit an article to the State Legislatures for the enfranchisement of women the situation would be vastly simplified and eventually the requisite three-fourths for ratification could be secured, but undoubtedly a number of States will have to follow the example of those in the far West in granting the suffrage before this is done. The question at present, therefore, may be considered as resting with the various Legislatures. With all the powerful influences above mentioned strongly intrenched and pitted against the women who come empty-handed, it is naturally a most difficult matter to secure the submission of an amendment where there is the slightest chance of its carrying. With the two exceptions of Colorado and Idaho, it may be safely asserted that in every case where one has been submitted it has been done simply to please the women and to get rid of them, and with the full assurance that it would not be carried. Two conspicuous examples of the impossibility of obtaining an amendment where it would be likely to receive a majority vote are to be found in California and Iowa. In the former State one went before the electors in 1896, and, although the conditions were most unfavorable and the strongest possible fight was made against it, so large an affirmative sentiment was developed that it was clearly evident it would be carried on a second trial. Up to that time the women of this State had very little difficulty in securing suffrage bills, but since then the Legislature has persistently refused to submit another amendment. (See chapter on California.)[Pg xxi]

In probably no State is the general sentiment so strongly in favor of woman suffrage as in Iowa, and yet for the past thirty years the women have tried in vain to secure from the Legislature the submission of an amendment—simply an opportunity to carry their case to the electors. (See chapter on Iowa.) The politics of that State is practically controlled by the great brewing interests and the balance of power rests in the German vote. It is believed that woman suffrage would be detrimental to their interests and they will not allow it. Here, as in many States, a resolution for an amendment must be acted upon by two successive Legislatures. If a majority of either party should pass this resolution, the enemy would be able to defeat its nominees for the next Legislature before the women could get the chance to vote for them. In other words, all the forces hostile to woman suffrage are already enfranchised and are experienced, active and influential in politics, while the women themselves can give no assistance, and the men in every community who favor it are very largely those who have not an aggressive political influence. This very refusal of certain Legislatures to let the voters pass upon the question is the strongest possible indication that they fear the result. If women could be enfranchised simply by an Act of Congress they would have an opportunity to vote for their benefactors at the same time as the enemies would vote against them, and thus the former would not, as at present, run the risk of personal defeat and the overthrow of their party by espousing the cause of woman suffrage.

If, however, Legislatures were willing to submit the question it is doubtful whether, under present conditions, it could be carried in any large number of States, as the same elements which influence legislators act also upon the voters through the party "machines." Amendments to strike the word "male" from the suffrage clause of the Constitution have been submitted by ten States, and by five of these twice—Kansas, 1867-94; Michigan, 1874; Colorado, 1877-93; Nebraska, 1882; Oregon, 1884-1900; Rhode Island, 1886; Washington, 1889-98; South Dakota, 1890-98; California, 1896; Idaho, 1896. Out of the fifteen trials the amendment has been adopted but twice—in Colorado and Idaho. In these two cases it was indorsed by all the political parties and carried with their permission. Wyoming and Utah placed equal[Pg xxii] suffrage in the constitution under which they entered Statehood. In both, as Territories, women had had the full franchise—in Wyoming twenty-one and in Utah seventeen years—and public sentiment was strongly in favor. In the States where the question was defeated it had practically no party support.

Aside from all political hostility, however, woman suffrage has to face a tremendous opposition from other sources. The attitude of a remonstrant is the natural one of the vast majority of people. Their first cry on coming into the world, if translated, would be, "I object." They are opposed on principle to every innovation, and the greatest of these is the enfranchisement of women. To grant woman an equality with man in the affairs of life is contrary to every tradition, every precedent, every inheritance, every instinct and every teaching. The acceptance of this idea is possible only to those of especially progressive tendencies and a strong sense of justice, and it is yet too soon to expect these from the majority. If it had been necessary to have the consent of the majority of the men in every State for women to enter the universities, to control their own property, to engage in the various professions and occupations, to speak from the public platform and to form great organizations, in not one would they be enjoying these privileges to-day. It is very probable that this would be equally true if they had depended upon the permission of a majority of women themselves. They are more conservative even than men, because of the narrowness and isolation of their lives, the subjection in which they always have been held, the severe punishment inflicted by society on those who dare step outside the prescribed sphere, and, stronger than all, perhaps, their religious tendencies through which it has been impressed upon them that their subordinate position was assigned by the Divine will and that to rebel against it is to defy the Creator. In all the generations, Church, State and society have combined to retard the development of women, with the inevitable result that those of every class are narrower, more bigoted and less progressive than the men of that class.

While the girls are crowding the colleges now until they threaten to exceed the number of boys, the demand for the higher education was made by the merest handful of women and granted by an equally small number of men, who, on the boards of trustees,[Pg xxiii] were able to do so, but it would have been deferred for decades if it had depended on a popular vote of either men or women. The pioneers in the professions found their most trying opposition from other women, instigated by the men who did their thinking for them to believe that the whole sex was being disgraced. Married women almost universally were opposed to laws which would give them control of their property, being assured by their masculine advisers that this would deprive them of the love and protection of their husbands. Public sentiment was wholly opposed to these laws and no such objections ever have been made in Legislatures even to woman suffrage as were urged against allowing a wife to own property. The contest was won by the smallest fraction of women and a few strong, far-seeing men, the latter actuated not alone by a sentiment of justice but also by the desire of preventing husbands from squandering the property which fathers had accumulated and wished to secure to their daughters, and fortunate indeed was it that this action did not have to be ratified by the voters.

There are in the United States between three and four million women engaged in wage-earning occupations outside of domestic service. Would this be possible had they been obliged to have the duly recorded permission of a majority of all the men over twenty-one years old? If the question were submitted to the votes of these men to-day whether women should be allowed to continue in these employments and enter any and all others, would it be carried in the affirmative in a single State?

And yet this prejudiced, conservative and in a degree ignorant and vicious electorate possesses absolutely the power to withhold the suffrage from women. A large part of it is composed of foreign-born men, bringing from the Old World the most primitive ideas of the degraded position which properly belongs to woman. Another part is addicted to habits with which it never would give women the chance to interfere. Boys of twenty-one form another portion, fully imbued with a belief in woman's inferiority which only experience can eradicate. Men of the so-called working classes vote against it because they fear to add to the power of the so-called aristocracy. The latter oppose it because they think the suffrage already has been too widely extended and ought to be curtailed instead of expanded.[Pg xxiv] The old fogies cast a negative ballot because they believe woman ought to be kept in her "sphere," and the strictly orthodox because it is not authorized by the Scriptures. A large body who are "almost persuaded," but have some lingering doubts as to the "expediency," satisfy their consciences for voting "no" by saying that the women of their family and acquaintance do not want it. Thus is the most valuable of human rights—the right of individual representation—made the football of Legislatures, the shuttlecock of voters, kicked and tossed like the veriest plaything in utter disregard of the vital fact that it is the one principle above all others on which the Government is founded.

Nevertheless there is abundant reason for belief that, in the face of all the forces which are arrayed against it, this measure could be carried in almost any State where the women themselves were a unit or even very largely in the majority in favor of it. In the indifference, the inertia, the apathy of women lies the greatest obstacle to their enfranchisement. Investigation in States where a suffrage amendment has been voted on has shown that practically every election precinct where a thorough canvass was made and every voter personally interviewed by the women who resided in it, was carried in favor. Some men of course can not be moved, but many who never have given the subject any thought can be set to thinking; while there is in the average man a latent sense of justice which responds to the persuasion of a woman who comes in person and says, "I ask you to grant me the same rights which you yourself enjoy; I am your neighbor; I pay taxes just as you do; our interests are identical; give me the same power to protect mine which you possess to protect yours." A man would have to be thoroughly hardened to vote "no" after such an appeal, but if he were let alone he could do so without any qualms. The same situation obtains in the family and in social life. The average man would not vote against granting women the franchise if all those of his own family and the circle of his intimate friends brought a strong pressure to bear upon him in its favor. The measure could be carried against all opposition if every clergyman in every community would urge the women of his congregation to work for it, assuring them of the sanction of the church and the blessing[Pg xxv] of God, and showing them how vastly it would increase their power for good.

Every privilege which has been granted women has tended to develop them, until their influence is incomparably stronger at the present time than ever before. Their great organizations are a power in every town and city. If these throughout a State would unite in a determined effort to secure the franchise, bringing to bear upon legislators the demands of thousands of women, high and low, rich and poor, of all classes and conditions, they would be compelled to yield; and the same amount of influence would carry the amendment with the voters. But the petitioners for the suffrage are in the minority. There are many obvious reasons for this, and one of them, paradoxical as it may seem, is because so much already has been gained. Woman in general now finds her needs very well supplied. If she wants to work she has all occupations to choose from. If she desires an education the schools and colleges are freely opened to her. If she wishes to address the public by pen or voice the people hear her gladly. The laws have been largely modified in her favor, and where they might press they are seldom enforced. She may accumulate and control property; she may set up her own domestic establishment and go and come at will. If the workingwoman finds herself at a disadvantage she has not time and often not ability to seek the cause until she traces it to disfranchisement, and if she should do so she is too helpless to make a contest against it. Those women who "have dwelt, since they were born, in well-feathered nests and have never needed do anything but open their soft beaks for the choicest little grubs to be dropped into them," can not be expected to feel or see any necessity for the ballot. Nor will the woman half way between, absorbed in her church, her clubs, her charities and her household, make the philosophical study necessary to show that she could do larger and more effective work for all of these if she possessed the great power which lies in the suffrage. Even women of much wealth who are not idle, self-centered and indifferent to the needs of humanity, but are giving munificently for religious, educational and philanthropic purposes, have not been aroused in any large number to the necessity of the suffrage, for reasons which are evident.

Reforms of every kind are inaugurated and carried forward[Pg xxvi] by a minority, and there is no reason why this one should prove an exception. In not an instance has a majority of any class of men demanded the franchise, and there is no precedent for expecting the majority of women to do so. It will have to be gained for them by the foresight, the courage and the toil of the few, just as all other privileges have been, and they will enter into possession with the same eagerness and unanimity as has marked their acceptance of the others.

With this mass of prejudice, selfishness and inertia to overcome is there any hope of future success? Yes, there is a hope which amounts to a certainty. Nothing could be more logical than a belief that where one hundred privileges have been opposed and then ninety-nine of them granted, the remaining one will ultimately follow. While women still suffer countless minor disadvantages, the fundamental rights have largely been secured except the suffrage. This, as has been pointed out, is most difficult to obtain because it is intrenched in constitutional law and because it represents a more radical revolution than all the others combined. The softening of the bitter opposition of the early days through the general spirit of progress has been somewhat counteracted by a modern skepticism as to the supreme merit of a democratic government and a general disgust with the prevalent political corruption. This will continue to react strongly against any further extension of the suffrage until men can be made to see that a real democracy has not as yet existed, but that the dangerous experiment has been made of enfranchising the vast proportion of crime, intemperance, immorality and dishonesty, and barring absolutely from the suffrage the great proportion of temperance, morality, religion and conscientiousness; that, in other words, the worst elements have been put into the ballot-box and the best elements kept out. This fatal mistake is even now beginning to dawn upon the minds of those who have cherished an ideal of the grandeur of a republic, and they dimly see that in woman lies the highest promise of its fulfilment. Those who fear the foreign vote will learn eventually that there are more American-born women in the United States than foreign-born men and women; and those who dread the ignorant vote will study the statistics and see that the percentage of illiteracy is much smaller among women than among men.[Pg xxvii]

The consistent tendency since the right to individual representation was established by the Revolutionary War has been to extend this right, until now every man in the United States is enfranchised. While a few, usually those who are too exclusive to vote themselves, insist that this is detrimental to the electorate, the vast majority hold that in numbers there is the safety of its being more difficult to purchase or mislead; that even the ignorant may vote more honestly than the educated; that more knowledge and judgment can be added through ten million electors than through five; and also that by this universal male suffrage it is made impossible for one class of men to legislate against another class, and thus all excuse for anarchy or a resort to force is removed. Added to these advantages is the developing influence of the ballot upon the individual himself, which renders him more intelligent and gives him a broader conception of justice and liberty. All of these conditions must lead eventually to the enfranchising of the only remaining part of the citizenship without this means of protection and development.

The gradual movement in this direction in the United States is seen in the partial extension of the franchise which has taken place during the past thirty-three years, or within one generation. During this time over one-half of them have conferred School Suffrage on women; one has granted Municipal Suffrage; four a vote on questions of taxation; three have recognized them in local matters, and a number of cities have given such privileges as were possible by charter. Since 1890 four States, by a majority vote of the electors, have enfranchised 200,000 women by incorporating the complete suffrage in their constitutions, from which it never can be removed except by a vote of women themselves. During all these years there have been but two retrogressive steps—the disfranchising of the women of Washington Territory in 1888 by an unconstitutional decision of the Supreme Court, dictated by the disreputable elements then in control; and the taking away of the School Suffrage from all women of the second-class cities in Kentucky by its Legislature of 1902 for the purpose of eliminating the vote of colored women. In every other Legislature a bill to repeal any limited franchise which has been extended has been overwhelmingly voted down.

Another favorable sign is the action taken by Legislatures on[Pg xxviii] bills for the full enfranchisement of women. Formerly they were treated with contempt and ridicule and either thrown out summarily or discussed in language which the descendants of the honorable gentlemen who used it will regret to read. Now such bills are treated with comparative courtesy; a discussion is avoided wherever possible, members not wishing to go on record, but if forced it is conducted in a respectful manner; and, while usually rejected, the opposing majority is small, in many instances only just large enough to secure defeat, and frequently members have to change their votes to the negative as they find the measure is about to be carried. Several instances have occurred in the last year or two where the bill passed but during the night the party whip was applied with such force that the affirmative was compelled to reconsider its action the next day. There is little doubt that even now if members were free to vote their convictions a bill could be carried in many Legislatures.

A most encouraging sign is the attitude of the Press. Although the country papers occasionally refer to the suffrage advocates as hyenas, cats, crowing hens, bold wantons, unsexed females and dangerous home-wreckers—expressions which were common a generation ago—these are no longer found in metropolitan and influential newspapers. Scores of both city and country papers openly advocate the measure and scores of others would do so if they were not under the same control as the Legislatures. Ten years ago it was almost impossible to secure space in any paper for woman suffrage arguments. To-day several of the largest in the country maintain regular departments for this purpose, while the report of the press chairman of the National Association for 1901 stated that during the past eight months 175,000 articles on the subject had been sent to the press and a careful investigation showed that three-fourths of them had been published. In addition different papers had used 150 special articles, while the page of plate matter furnished every six weeks was extensively taken. New York reported 400 papers accepting suffrage matter regularly; Pennsylvania, 368; Iowa, 253; Illinois, 161; Massachusetts, 107, and other States in varying numbers. Since this question is very largely one of educating the people, the opening of the Press to its arguments is probably the most important advantage which has been gained.[Pg xxix]

The progress of public sentiment is strikingly illustrated in a comparison of the votes in those States which have twice submitted an amendment to their constitution that would give the suffrage to women. In Kansas such an amendment in 1867 received 9,070 ayes, 19,857 noes; in 1894, 95,302 ayes, 130,139 noes. The second time it was indorsed by the Populists and not by the Republicans, therefore the latter, who in that State are really favorable to the measure, largely voted against it in order that the Populists might not strengthen their party by appearing to carry it, and yet the percentage of opposition was considerably decreased. In Colorado in 1877 the vote stood 6,612 ayes, 14,055 noes; in 1893 the amendment was carried by 35,698 ayes, 29,461 noes—a majority of 6,237. Oregon in 1884 gave 11,223 ayes, 28,176 noes; in 1900, 26,265 ayes, 28,402 noes—an increase of 226 opponents and 15,042 advocates. The vote in Washington in 1889 was 16,527 ayes, 35,917 noes; in 1898, 20,171 ayes, 30,497 noes—the opposing majority reduced from 19,396 to 10,326, or almost one-half.

One is logically entitled to believe from these figures that the question will be carried in each of those States the next time it is voted on. It must be remembered that women go into all these campaigns with no political influence and practically no money, not enough to employ workers and speakers to make an approach to a thorough organization and canvass of the State; totally without the aid of party machinery; with no platform on which to present their cause except such as is granted by courtesy; and with no advocacy of it by the speakers on the platforms of the various parties. The increased majorities indicate solely that men are emerging from the bondage of tradition, prejudice and creed, and that when they can escape from the bondage of politics they will grant justice to women.

The very fact that women themselves are arousing from their inertia to the extent of organizing in opposition to what they term "the danger of having the ballot thrust upon them" shows life. While their enrollment is infinitesimal it has set women to thinking, and a number who have signed the declaration that they do not want the franchise, have for the first time been compelled to give the matter consideration and have decided that they do want it. The facts also that within a few years the[Pg xxx] membership of the National Suffrage Association has doubled; that auxiliaries have been formed in every State and Territory; that permanent headquarters have been established in New York; and that the revenues (almost wholly the contributions of women) have risen from the $2,000 or $3,000 per annum, which it was barely possible to secure half-a-dozen years ago, to $10,345 in 1899, $22,522 in 1900 (including receipts from Bazar), $18,290 in 1901—these facts are indisputable evidence of the growth of the sentiment among women. In this line of progress must be placed also the thousands of other organizations containing millions of women, which, although not including the suffrage among their objects, are engaged in efforts for better laws, civic improvements and a general advance in conditions that inevitably will bring them to realize the immense disadvantage of belonging to a class without political influence.

Nothing could be more illogical than the belief that a republic would confer every gift upon woman except the choicest and then forever withhold this; or that women would be content to possess all others and not eventually demand the one most valuable. The increasing number who are attending political conventions and crowding mass meetings until they threaten to leave no room for voters, are unmistakable proof that eventually women themselves and men also will see the utter absurdity of their disfranchised condition. The ancient objections which were urged so forcibly a generation or two ago have lost their force and must soon be retired from service. The charge of mental incapacity is totally refuted by the statistics of 1900 showing the percentage of girls in the High Schools to be 58.36 and of boys, 41.64; the number of girl graduates, 39,162; boys, 22,575; 70 per cent. of the public school teachers women; 40,000 women college graduates scattered throughout the country and 30,000 now in the universities, with the percentage of their increase in women students three times as great as that of men, and 431,153 women practicing in the various professions.

The charge of business incompetency is disproved by the 503,574 women who are engaged in trade and transportation, the 980,025 in agriculture and the 1,315,890 in manufacturing and mechanical pursuits. Every community also furnishes its special examples of the aptitude of women for business, now that they[Pg xxxi] are allowed a chance to manifest it. Statistics show further that one-tenth of the millionaires are women and that they are large property holders in every locality. Whether they earned or inherited their holdings, the fact remains that they are compelled to pay taxes on billions of dollars without any representation.

The military argument—that women must not vote because they can not fight—is seldom used nowadays, as it is so clearly evident that it would also disfranchise vast numbers of men; that the value of women in the perpetuation of the Government is at least equal to that of the men who defend it; and that there is no recognition in the laws by which the franchise is exercised of the slightest connection between a ballot and a bullet.

The most persistent objection—that if women are allowed to enter politics they will neglect their homes and families—is conclusively answered in the four States where they have had political rights for a number of years and domestic life still moves on just as in other places. In two of the four while Territories women had exercised the franchise from seventeen to twenty-one years, and yet a large majority of the men voted to grant it perpetually. Women do not love their families because compelled to do so by statute, or cling to their homes because there is no place for them outside. This same direful prediction was made at every advanced step, but, although the entire status of women has been changed, and they are largely engaged in the public work of every community, they are better and happier wives, mothers and housekeepers because they are more intelligent and live a broader life. But they are learning, and the world is learning, that their housekeeping qualities should extend to the municipality and their power of motherhood to the children of the whole nation, and that these should be expressed through this very politics from which they are so rigorously excluded.

The objections of the opponents have been so largely confuted that they have for the most part been compelled to make a last defense by declaring: "When the majority of women ask for the suffrage they may have it." By this very concession they admit that there is no valid reason for withholding it, and in thus arbitrarily doing so they are denying all representation to the minority, which is wholly at variance with republican principles. This is excused on the ground that the franchise is not a "right"[Pg xxxii] but a privilege to be granted or not as seems best to those in power. This was the Tory argument before the American Revolution, and, carried back to its origin, it upholds "the divine authority of kings." The law to put in force the one and only amendment ever added to our National Constitution to extend the franchise was entitled, "An act to enforce the right of citizens of the United States to vote;" and the amendment itself reads, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged." (See Chap. I.)

The readers of the present volume will not find such a story of cruel and relentless punishment inflicted upon advocates of woman suffrage as is related in the earlier volumes of this History, but the passing of rack and thumbscrew, of stake and fagot, does not mean the end of persecution in the world. Those who stand for this reform to-day do not tread a flower-strewn path. It is yet an unpopular subject, under the ban of society and receiving scant measure of public sympathy, but it must continue to be urged. If the assertion had been accepted as conclusive, that a measure which after years of advocacy is still opposed by the majority should be dropped, the greatest reforms of history would have been abandoned. The personal character of those who represent a cause, however, sometimes carries more weight than the numbers, and judged by this standard none has had stronger support than the enfranchisement of women[2].

The struggle of the Nineteenth Century was the transference of power from one man or one class of men to all men, it has been said, and while but one country in 1800 had a constitutional government, in 1900 fifty had some form of constitution and some degree of male sovereignty. Must the Twentieth Century be consumed in securing for woman that which man spent a hundred years in obtaining for himself? The determination of those engaged in this righteous contest was thus expressed by the president of the National Suffrage Association in her address at the annual convention of 1902:

Before the attainment of equal rights for men and women there will be years of struggle and disappointment. We of a younger generation have taken up the work where our noble and consecrated pioneers left it. We, in turn, are enlisted for life, and generations[Pg xxxiii] yet unborn will take up the work where we lay it down. So, through centuries if need be, the education will continue, until a regenerated race of men and women who are equal before man and God shall control the destinies of the earth.

But have we not reason to hope, in this era of rapid fulfilment—when in all material things electricity is accomplishing in a day what required months under the old régime—that moral progress will keep pace? And that as much stronger as the electric power has shown itself than the coarse and heavy forces of the stone and iron periods, so much superior will prove the noblesse oblige of the men and women of the present, achieving in a generation what was not possible to the narrow selfishness and ignorant prejudice of all the past ages?

A part of the magnificent plan to beautify Washington, the capital of the nation, is a colossal statue to American Womanhood. The design embodies a great arch of marble standing on a base in the form of an oval and broken by sweeps of steps. On either side are large bronze panels, bearing groups of figures. One of these will be a symbolic design showing the spirit of the people descending to lay offerings on woman's altar. Lofty pillars crowned by figures representing Victory, are to be placed at the approaches. Surmounting the arch will be the chief group of the composition, symbolizing Woman Glorified. She is rising from her throne to greet War and Peace, Literature and Art, Science and Industry, who approach to lay homage at her feet. Inside the arch is a memorial hall for recording the achievements of women.

How soon this symbol shall become reality and woman stand forth in all the glory of freedom to reach her highest stature, depends upon the use she makes of the opportunities already hers and the fraternal assistance she receives from man. Fearless of criticism, courageous in faith, let each take for a guide these inspiring words which it has been said the Puritan of old would utter if he could speak: "I was a radical in my day; be thou the same in thine! I turned my back upon the old tyrannies and heresies and struck for the new liberties and beliefs; my liberty and my belief are doubtless already tyranny and heresy to thine age; strike thou for the new!"[Pg xxxiv]

[2] For partial list, see Appendix—Eminent Advocates of Woman Suffrage.

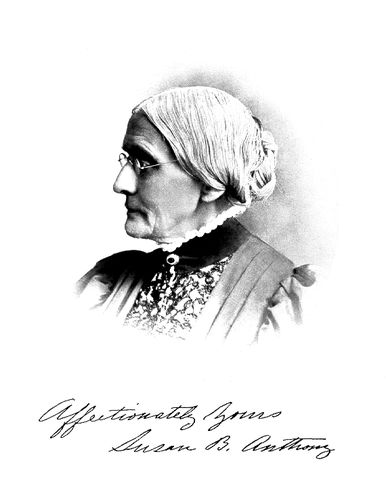

| Anthony, Susan B. | Frontispiece |

| Anthony, Mary S. | 848 |

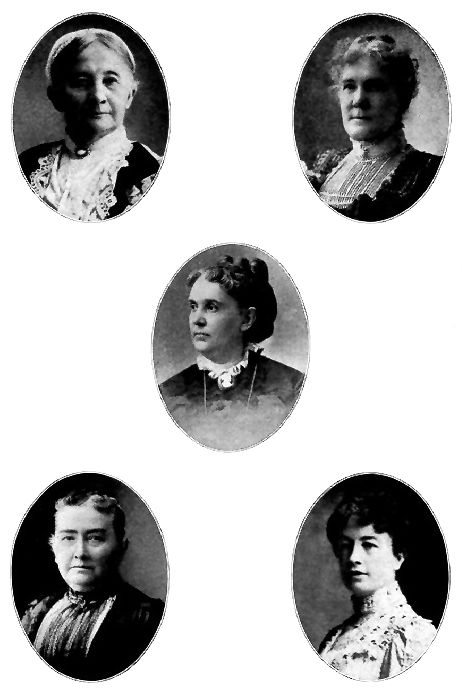

| Avery, Rachel Foster | 270 |

| Avery, Susan Look | 678 |

| Blackwell, Alice Stone | 270 |

| Blankenburg, Lucretia L. | 750 |

| Catt, Carrie Chapman | 388 |

| Chapman, Mariana W. | 848 |

| Clay, Laura | 270 |

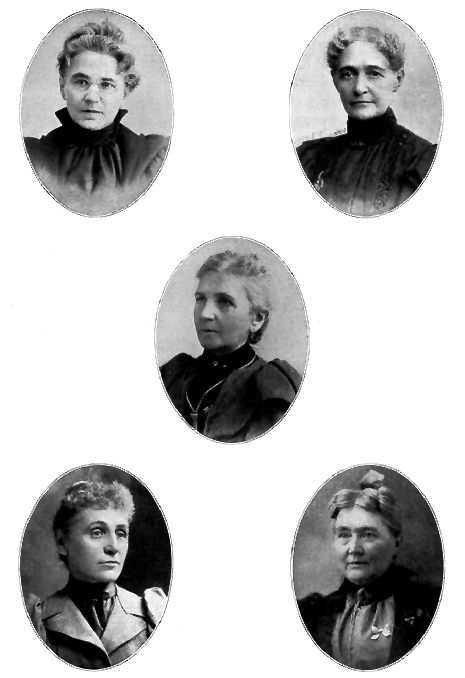

| Coggeshall, Mary J. | 948 |

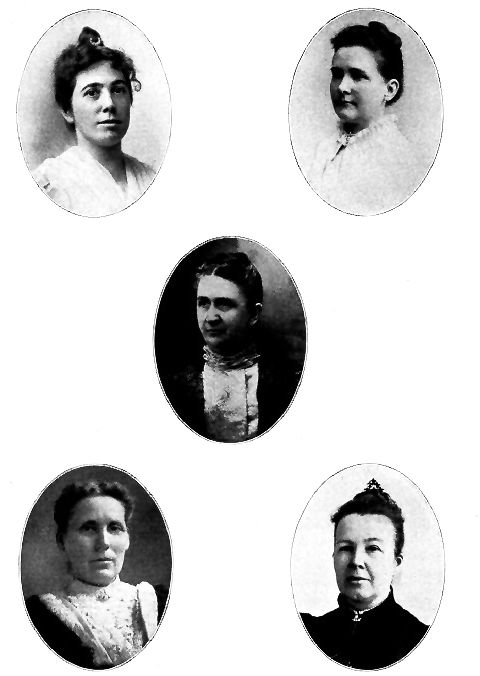

| Eaton, Dr. Cora Smith | 518 |

| Gordon, Kate M. | 678 |

| Greenleaf, Jean Brooks | 848 |

| Gregg, Laura A. | 518 |

| Hall, Florence Howe | 750 |

| Harper, Ida Husted | 1042 |

| Hatch, Lavina A. | 750 |

| Hayward, Mary Smith | 948 |

| Howard, Emma Shafter | 518 |

| Howland, Emily | 848 |

| Jenkins, Helen Philleo | 678 |

| Johns, Laura M. | 948 |

| McCulloch, Catharine Waugh | 270 |

| Meredith, Ellis | 518 |

| Mills, Harriet May | 750 |

| Nelson, Julia B. | 948 |

| Osborne, Elizabeth Wright | 848 |

| Shaw, Rev. Anna Howard | 128 |

| Southworth, Louisa | 678 |

| Spencer, Rev. Anna Garlin | 750 |

| Stanton, Elizabeth Cady | 188 |

| Swift, Mary Wood | 518 |

| Thomas, Mary Bentley | 678 |

| Upton, Harriet Taylor | 270 |

| Wells, Emmeline B. | 948 |

List of Illustrations xxxiv

Review of the Situationxiii-xxxiii

Pioneers break the ground — All their demands now practically

conceded except the Franchise — Why is this still refused? —

All other rights depend on Statute Law, suffrage on change of

Constitution — No other nation thus fettered — Further almost

insurmountable obstacles — Experience in many States — Either

dominant party would enfranchise women if it were sure of their

votes — Liquor interests and political "machines" allied in

opposition — They control the situation — Figures of votes on

Amendments — Majority of people born opponents of all

innovations — Character of electorate on which women must depend

— Indifference of women themselves — Reaction against a

democratic government — Facts showing steady progress of Woman

Suffrage — All signs favorable — Women in education and

business — Old objections dying out — Personal character of

advocates — Persecution not obsolete but the enfranchisement of

women inevitable.

Woman's Constitutional Right to Vote1-13

Early State constitutions provided against Woman Suffrage —

First demand for it — Women after the Civil War — "Male" first

used in National Constitution — Fourteenth Amendment — Endeavor

to make it include women — They attempt to vote — Susan B.

Anthony's trial — Case of Virginia L. Minor — Supreme Court

decisions — Suffrage as a right — Arguments for the Federal

Franchise — National Association decides to try only for new

Amendment — Hearings before Congressional Committees — Reports

of these committees — Debate in Congress.

The National Suffrage Convention of 188414-30

Forming of National Association in 1869 — Washington selected

for annual conventions — Call for that of '84 — Extracts from

speeches on Kentucky Laws for Women — Woman before the Law —

Outrage of Disfranchisement — Ethics of Woman Suffrage —

England vs. the United States — Bishop Matthew Simpson in Favor

of Woman's Enfranchisement — Resolutions and Plan of Work —

Memorial to Wendell Phillips — Miss Anthony on Disfranchisement

a Disgrace — Matilda Joslyn Gage on The Feminine in the

Sciences.

Congressional Hearings and Reports of 188431-55

Debate in the House on a Special Woman Suffrage Committee —

Extracts from speeches of John H. Reagan on Awful Effects of

Woman Suffrage — James B. Belford on Woman's Right to a Special

Committee — J. Warren Keifer on Justice of the Enfranchisement

of Women — John D. White on Woman's Right to be Heard — Hearing

before Senate Committee — Interdependence of Men and Women —

Woman Suffrage a Paramount Question — A Right does not Depend on

a Majority's Asking for It — Woman's Ballot for the Good of the

Race — Preponderance of Foreign Vote — Miss Anthony on Action

by Congress vs. Action by Legislatures — Elizabeth Cady Stanton

on Self-Government the Best Means of Self-Development; moral need

of woman's ballot, men as natural protectors, inherent right of

self-representation — Favorable Senate Report — Adverse House

Report by William C. Maybury — Editorial comment — Luke P.

Poland on Men Should Represent Women — Strong Report in Favor by

Thomas B. Reed, Ezra B. Taylor, Moses A. McCoid, Thomas M.

Browne.

The National Suffrage Convention of 188556-69

Startling descriptions of delegates' attire — Mrs. Stanton on

Separate Spheres an Impossibility — Discussion on resolution

denouncing Religious Dogmas — Criticism by ministers — Great

speech in favor of Woman Suffrage in the U. S. Senate by Thomas

W. Palmer; action by Congress a necessity, Scriptures not opposed

to the equality of woman, figures of women's vote, State needs

woman's ballot.

The National Suffrage Convention of 188670-84

Relation of the Woman Suffrage Movement to the Labor Question —

Take Down the Barriers — German and American Independence

Contrasted — Resolution condemning Creeds and Dogmas again

discussed — Woman's Right to Vote under Fourteenth Amendment —

Disfranchisement Cuts Women's Wages — One-half No Right to a

Vote on Liberties of Other Half — Woman Suffrage Necessary for

Life of Republic — America lags behind in granting political

rights to women — Minority House Report in favor of a Sixteenth

Amendment by Ezra B. Taylor, W. P. Hepburn, Lucian B. Caswell, A.

A. Ranney; men hold franchise by force, women require it for

development, history of woman one of wrong and outrage,

Government needs woman's vote, no excuse for waiting till

majority demand it.

First Discussion and Vote in U. S. Senate, 188785-111

Joint Resolution for Sixteenth Amendment extending Right of

Suffrage to Women — Able speech of Henry W. Blair; Government[Pg xxxvii]

founded on equality of rights, no connection between the vote and

ability to fight, property qualification an invasion of natural

right, man's deification of woman a shallow pretense, no such

thing as household suffrage here, maternity qualifies woman to

vote, fear of family dissension not a valid excuse — Joseph E.

Brown replies; Creator intended spheres of men and women to be

different, man qualified by physical strength to vote, caucuses

and jury duty too laborious for women, they are queens,

princesses and angels, they would neglect their families to go

into politics, the delicate and refined would feel compelled to

vote, only the vulgar and ignorant would go to the polls, ballot

would not help workingwomen, husbands would compel wives to vote

as they dictated — Editorial comment — Joseph N. Dolph supports

the Resolution; if but one woman wants the suffrage it is tyranny

to refuse it, neither in nature nor revealed will of God is there

anything to forbid, contest for woman suffrage a struggle for

human liberty, its benefits where exercised — James B. Eustis

objects — George G. Vest depicts the terrible dangers, negro

women all would vote Republican ticket, husband does not wish to

go home to embrace of female ward politician, women too emotional

to vote, suffrage not a right, we must not unsex our mothers and

wives — Editorial comment — George F. Hoar defends woman

suffrage; arguments against it are against popular government,

Senators Brown and Vest have furnished only gush and emotion —

Senator Blair closes debate with an appeal that women may carry

their case to the various Legislatures — Vote on submitting an

Amendment, 16 yeas, 34 nays.

The National Suffrage Convention of 1887112-123

Bishop John P. Newman favors Woman Suffrage — Mrs. Stanton's

sarcastic comments on the speeches of Senators Brown and Vest —

Lillie Devereux Blake's satire on the Rights of Men — Isabella

Beecher Hooker on the Constitutional Rights of Women — Woman of

the Present and Past — Delegate Joseph M. Carey on Woman

Suffrage in Wyoming — Authority of Congress to Enfranchise Women

— Zerelda G. Wallace on Woman's Ballot a Necessity for the

Permanence of Free Institutions; the lack of morality in

Government has caused the downfall of nations — Resolutions —

U. S. Treasurer Spinner first to employ women in a Government

department.

International Council of Women — Hearing of 1888124-142

Origin of the Council — Call issued by National Suffrage

Association — Official statistics of this great meeting —

Eloquent sermon of the Rev. Anna Howard Shaw on the Heavenly

Vision; release of woman from bondage of centuries, crucifixion

of reformers, the visions of all ages — Miss Anthony opens the

Council — Mrs. Stanton's address; psalms of women's lives in a

minor key, sympathy as a civil agent powerless until coined into

law, women have been mere echoes of[Pg xxxviii] men — Council demands all

employments shall be open to women, equal pay for equal work, a

single standard of morality — Forming of permanent National and

International Councils — Convention of Suffrage Association —

Mrs. Stanton expounds National Constitution to Senate Committee

and shows the violation of its provisions in their application to

women — Mrs. Ormiston Chant makes address — Also Julia Ward

Howe — Frances E. Willard pleads for enfranchisement.

The National Suffrage Convention of 1889143-157

Official Call shows non-partisan character of the demand for

Woman Suffrage — Senator Blair makes clear presentation of

woman's right to vote for Representatives in Congress under the

Federal Constitution — Mrs. Stanton ridicules women for passing

votes of thanks to men for restoring various minor privileges

which they had usurped — Hebrew Scriptures not alone the root of

woman's subjection — Representative William D. Kelley speaks —

Foreign and Catholic vote contrasted with American and Protestant

— The Position of Woman in Marriage — Miss Anthony on Woman's

Attempt to Vote under the Fourteenth Amendment — The Coming Sex

— Woman's Bill of Rights — Favorable report from Committee,

Senators Blair, Charles B. Farwell, Jonathan Chace, Edward O.

Wolcott.

National-American Convention of 1890158-174