[15]

[Contents]

Eskimo Folk-Tales

The Two Friends Who Set Off to Travel Round the

World

Once there were two men who desired to travel round the world, that

they might tell others what was the manner of it.

This was in the days when men were still many on the earth, and

there were people in all the lands. Now we grow fewer and fewer. Evil

and sickness have come upon men. See how I, who tell this story, drag

my life along, unable to stand upon my feet.

The two men who were setting out had each newly taken a wife, and

had as yet no children. They made themselves cups of musk-ox horn, each

making a cup for himself from one side of the same beast’s head.

And they set out, each going away from the other, that they might go by

different ways and meet again some day. They travelled with sledges,

and chose land to stay and live upon each summer.

It took them a long time to get round the world; they had children,

and they grew old, and then their children also grew old, until at last

the parents were so old that they could not walk, but the children led

them.

And at last one day, they met—and of their drinking horns

there was but the handle left, so many times had they drunk water by

the way, scraping the horn against the ground as they filled them.

“The world is great indeed,” they said when they

met.

They had been young at their starting, and now they were old men,

led by their children.

Truly the world is great. [16]

[Contents]

The Coming of Men, A Long, Long While Ago

Our forefathers have told us much of the coming of earth, and of

men, and it was a long, long while ago. Those who lived long before our

day, they did not know how to store their words in little black marks,

as you do; they could only tell stories. And they told of many things,

and therefore we are not without knowledge of these things, which we

have heard told many and many a time, since we were little children.

Old women do not waste their words idly, and we believe what they say.

Old age does not lie.

A long, long time ago, when the earth was to be made, it fell down

from the sky. Earth, hills and stones, all fell down from the sky, and

thus the earth was made.

And then, when the earth was made, came men.

It is said that they came forth out of the earth. Little children

came out of the earth. They came forth from among the willow bushes,

all covered with willow leaves. And there they lay among the little

bushes: lay and kicked, for they could not even crawl. And they got

their food from the earth.

Then there is something about a man and a woman, but what of them?

It is not clearly known. When did they find each other, and when had

they grown up? I do not know. But the woman sewed, and made

children’s clothes, and wandered forth. And she found little

children, and dressed them in the clothes, and brought them home.

And in this way men grew to be many.

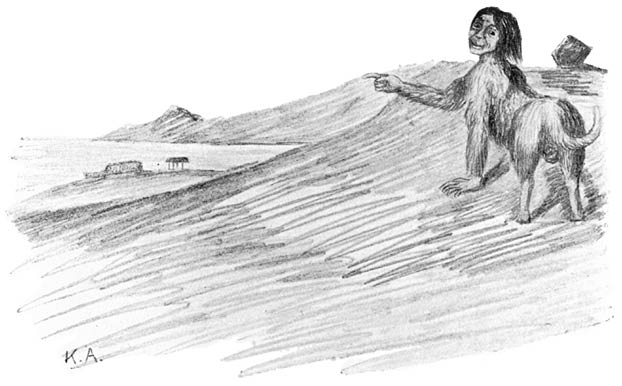

And being now so many, they desired to have dogs. So a man went out

with a dog leash in his hand, and began to stamp on the ground, crying

“Hok—hok—hok!” Then the dogs came hurrying out

from the hummocks, and shook themselves violently, for their coats were

full of sand. Thus men found dogs. [17]

But then children began to be born, and men grew to be very many on

the earth. They knew nothing of death in those days, a long, long time

ago, and grew to be very old. At last they could not walk, but went

blind, and could not lie down.

Neither did they know the sun, but lived in the dark. No day ever

dawned. Only inside their houses was there ever light, and they burned

water in their lamps, for in those days water would burn.

But these men who did not know how to die, they grew to be too many,

and crowded the earth. And then there came a mighty flood from the sea.

Many were drowned, and men grew fewer. We can still see marks of that

great flood, on the high hill-tops, where mussel shells may often be

found.

And now that men had begun to be fewer, two old women began to speak

thus:

“Better to be without day, if thus we may be without

death,” said the one.

“No; let us have both light and death,” said the

other.

And when the old woman had spoken these words, it was as she had

wished. Light came, and death.

It is said, that when the first man died, others covered up the body

with stones. But the body came back again, not knowing rightly how to

die. It stuck out its head from the bench, and tried to get up. But an

old woman thrust it back, and said:

“We have much to carry, and our sledges are small.”

For they were about to set out on a hunting journey. And so the dead

one was forced to go back to the mound of stones.

And now, after men had got light on their earth, they were able to

go on journeys, and to hunt, and no longer needed to eat of the earth.

And with death came also the sun, moon and stars.

For when men die, they go up into the sky and become brightly

shining things there. [18]

[Contents]

Nukúnguasik, Who Escaped from the Tupilak1

Nukúnguasik, it is said, had land in a place with many

brothers. When the brothers made a catch, they gave him meat for the

pot; he himself had no wife.

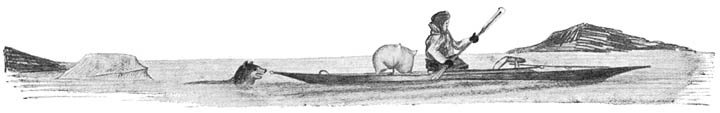

One day he rowed northward in his kayak, and suddenly he took it

into his head to row over to a big island which he had never visited

before, and now wished to see. He landed, and went up to look at the

land, and it was very beautiful there.

And here he came upon the middle one of many brothers, busy with

something or other down in a hollow, and whispering all the time. So he

crawled stealthily towards him, and when he had come closer, he heard

him whispering these words:

“You are to bite Nukúnguasik to death; you are to bite

Nukúnguasik to death.”

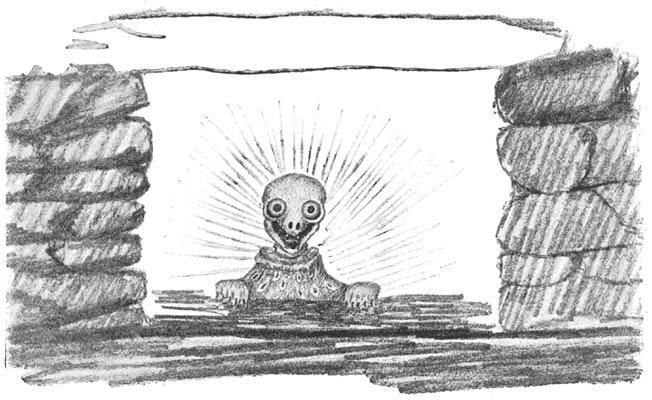

And then it was clear that he was making a Tupilak, and stood there

now telling it what to do. But suddenly Nukúnguasik slapped him

on the side and said: “But where is this

Nukúnguasik?”

And the man was so frightened at this that he fell down dead.

And then Nukúnguasik saw that the man had been letting the

Tupilak sniff at his body. And the Tupilak was now alive, and lay there

sniffing. But Nukúnguasik, being afraid of the Tupilak, went

away without trying to harm it.

Now he rowed home, and there the many brothers were waiting in vain

for the middle one to return. At last the day dawned, and still he had

not come. And daylight came, and then as they were preparing to go out

in search of him, the eldest of them said to Nukúnguasik:

“Nukúnguasik, come with us; we must search for

him.”

And so Nukúnguasik went with them, but as they found nothing,

he said:

[19]

“Would it not be well to go and make search over on that

island, where no one ever goes?”

And having gone on to the island, Nukúnguasik said:

“Now you can go and look on the southern side.”

When the brothers reached the place, he heard them cry out, and the

eldest said:

“O wretched one! Why did you ever meddle with such a thing as

this!”

And they could be heard weeping all together about the dead man.

And now Nukúnguasik went up to them, and there lay the

Tupilak, still alive, and nibbling at the body of the dead man. But the

brothers buried him there, making a mound of stones above him. And then

they went home.

Nukúnguasik lived there as the oldest in the place, and died

at last after many years.

Here I end this story: I know no more. [20]

[Contents]

Qujâvârssuk

A strong man had land at Ikerssuaq. The only other one there was an

old man, one who lived on nothing but devil-fish; when the strong man

had caught more than he needed, the old man had always plenty of meat,

which was given him in exchange for his fish.

The strong one, men say, he who never failed to catch seal when he

went out hunting, became silent as time went on, and then very silent.

And this no doubt was because he could get no children.

The old one was a wizard, and one day the strong one came to him and

said:

“To-morrow, when my wife comes down to the shore close by

where you are fishing, go to her. For this I will give you something of

my catch each day.”

And this no doubt was because he wanted his wife to have a child,

for he wished greatly to have a child, and could not bring it

about.

The old man did not forget those words which were said to him.

And to his wife also, the strong one said:

“To-morrow, when the old one is out fishing, go you down

finely dressed, to the shore close by.”

And she did it as he had said. When they had slept and again

awakened, she watched to see when the old one went out. And when he

rowed away, she put on her finest clothes and followed after him along

the shore. When she came in sight of him, he lay out there fishing.

Then eagerly she stood up on the shore, and looked out towards him. And

now he looked at her, and then again out over the sea, and this went on

for a long time. She stood there a long time in vain, looking out

towards him, but he would not come in to where she was, and therefore

she went home. As soon as she had come home, her husband rowed up to

the old one, and asked:

“Did you not go to my wife to-day?”

The old one said: [21]

“No.”

And again the strong one said a second time:

“Then do not fail to go to her to-morrow.”

But when the old one came home, he could not forget the strong

man’s words. In the evening, the strong one said that same thing

again to his wife, and a second time told her to go to the old one.

They slept, and awakened, and the strong man went out hunting as was

his wont. Then his wife waited only until the old one had gone out, and

as soon as he was gone, she put on her finest clothes and followed

after. When she came in sight of the water, the old one was sitting

there in his boat as on the other days, and fishing. Now the old one

turned his head and saw her, and he could see that she was even more

finely dressed than on the day before. And now a great desire of her

came over him, and he made up his mind to row in to where she was. He

came in to the land, and stepped out of his kayak and went up to her.

And now he went to her this time.

Then he rowed out again, but he caught scarcely any fish that

day.

When only a little time had gone, the strong man came rowing out to

him and said:

“Now perhaps you have again failed to go to my

wife?”

When these words were spoken, the old one turned his head away, and

said:

“To-day I have not failed to be with her.”

When the strong one heard this, he took one of the seals he had

caught, and gave it to the old man, and said:

“Take this; it is yours.”

And in this way he acted towards him from that time. The old one

came home that day dragging a seal behind him. And this he could often

do thereafter.

When the strong one came home, he said to his wife:

“When I go out to-morrow in my kayak, it is not to hunt seal;

therefore watch carefully for my return when the sun is in the

west.”

Next day he went out in his kayak, and when the sun was in the west,

his wife went often and often to look out. And once when she went thus,

she saw that he had come, and from that moment she was no longer

sleepy. [22]

As the strong one came nearer and nearer to land, he paddled more

and more strongly.

Now his wife went down to that place where he was about to land, and

turned and sat down with her back to the sea. The man unfastened his

hunting fur from the ring of his kayak, and put his hand into the back

of the kayak, and took out a sea serpent, and struck his wife on the

back. At this she felt very cold, and her skin smarted. Then she stood

up and went home. But her husband said no word to her. Then they slept,

and awakened, and then the old one came to them and said:

“Now you must search for the carrion of a cormorant, with only

the skeleton remaining, for your wife is with child.”

And the strong one went out eagerly to search for this.

One day, paddling southward in his kayak, as was his custom, he

started to search all the little bird cliffs. And coming to the foot of

one of them, he saw that which he so greatly wished to see; the carrion

of a big cormorant, which had now become a skeleton. It lay there quite

easy to see. But there was no way of coming to the place where it was,

not from above nor from below, nor from the side. Yet he would try. He

tied his hunting line fast to the cross thongs on his kayak, and thrust

his hand into a small crack a little way up the cliff. And now he tried

to climb up there with his hands alone. And at last he got that

skeleton, and came down in the same way back to his kayak, and got into

it, and rowed away northward to his home. And almost before he had

reached land, the old one came to him, and the cormorant skeleton was

taken out of the kayak. Now the old one trembled all over with

surprise. And he took the skeleton, and put it away, and said:

“Now you must search for a soft stone, which has never felt

the sun, a stone good to make a lamp of.”

And the strong man began to search for such a stone.

Once when he was on this search, he came to a cliff, which stood in

such a place that it never felt the sun, and here he found a fine lamp

stone. And he brought it home, and the old one took it and put it

away.

A few days passed, and then the strong one’s wife began to

feel the birth-pangs, and the old one went in there at once with his

own wife. Then she bore a son, and when he was born, the strong man

said to the old one: [23]

“This is your child; name him after some dead one.”1

“Let him be named after him who died of hunger in the north,

at Amerdloq.”

This the old one said. And then he said:

“His name shall be Qujâvârssuk!”

And in this way the old one gave him that name.

Now Qujâvârssuk grew up, and when he was grown big

enough, the strong man said to the old one:

“Make a kayak for him.”

Now the old one made him a kayak, and the kayak was finished. And

when it was finished, he took it by the nose and thrust him out into

the water to try it, but without loosing his hold. And when he did

this, there came one little seal up out of the water, and others also.

This was a sign that he should be a strong man, a chief, when the seals

came to him so. When he drew him out of the water, they all went down

again, and not a seal remained.

Now the old one began to make hunting things. When they were

finished, and there was nothing more to be done in making them, and he

thought the boy was of a good age to begin going out to hunt seal, he

said to the strong one:

“Now row out with him, for he must go seal hunting.”

Then he rowed out with him, and when they had come so far out that

they could not see the bottom, he said:

“Take the harpoon point with its line, and fix it on the

shaft.”

They had just made things ready for their hunting and rowed on

farther, when they came to a flock of black seal.

The strong one said to him:

“Now row straight at them.”

And then he rowed straight at them, and he lifted his harpoon and he

threw it and he struck. And this he did every day in the same manner,

and made a catch each time he went out in his kayak.

Then some people who had made a wintering place in the south heard,

in a time of hunger, of Qujâvârssuk, the strong man who

never suffered want. And when they heard this, they began to come and

visit the place where he had land. In this way there came once a man

who was called Tugto, and his wife. And while they were

there—they [24]were both great wizards—the man and his

wife began to quarrel, and so the wife ran away to live alone in the

hills. And now the man could not bring back his wife, for he was not so

great a wizard as she. And when the people who had come to visit the

place went away, he could do nothing but stay there.

One day when he was out hunting seal at Ikerssuaq, he saw a big

black seal which came up from the bottom with a red fish in its

mouth.

Now he took bearings by the cliffs of the place where the seal went

down, and after that time, when he was out in his kayak, he took up all

the bird wings that he saw, and fastened all the pinion feathers

together.

Tugto was a big man, yet he had taken up so much of this that it was

a hard matter for him to carry it when he took it on his back, and then

he thought it must be enough for that depth of water.

At last the ice lay firm, and when the ice lay firm, he began to

make things ready to go out and fish. One morning he woke, and went

away over land. He came to a lake, and walked over it, and came again

on to the land. And thus he came to the place where lay that water he

was going to fish, and he went out on the ice while it was still

morning. Then he cut a great hole in the ice, and just as he cast out

the weight on his line, the sun came up. It came quite out, and went

across the sky, all in the time he was letting out his line. And not

until the sun had gone half through the day did the weight reach the

bottom. Then he hauled up the line a little way, and almost before it

was still, he felt a pull. And he hauled it up, and it was a mighty sea

perch. This he killed, but did not let down his line a second time, for

in that way it would become evening. He cut a hole in the lower jaw of

the fish, and put in a cord to carry it with. And when he took it on

his head, it was so long that the tail struck against his heel.

Then in this manner he walked away, and came to land. When he came

to the big lake he had walked over in the morning, he went out on it.

But when he had come half the way over, the ice began to make a noise,

and when he looked round, it seemed to him that the noise in the ice

was following him from behind.

Now he went away running, but as he ran he fainted suddenly away,

and lay a long time so. When he woke again, he was lying down. He

thought a little, and then he remembered. “Au: I am [25]running

away!” And then he got up and turned round, but could not find a

break in the ice anywhere. But he could feel in himself that he had now

become a much greater wizard than before.

He went on farther, and chose his way up over a little hilly slope,

and when he could see clearly ahead, he perceived a mighty beast.

It was one of those monsters which men saw in the old far-off times,

quite covered with bird-skins. And it was so big that not a twitch of

life could be seen in it. He was afraid now, and turned round, until he

could no longer see it. Then he left that way, and came out into

another place, where he saw another looking just the same. He now went

back again in such a manner that it could not find him, but then he

remembered that a wizard can win power to vanish away, even to vanish

into the ground, if he can pull to pieces the skin of such a

monster.

When his thoughts had begun to work upon this, he threw away his

burden and went towards it and began to wrestle with it. And it was not

a long time before he began to tear its covering in pieces; the flesh

on it was not bigger than a thumb. Then he went away from it, and took

up his burden again on his head, and went wandering on. When he was

again going along homewards, he felt in himself that he had become a

great wizard, and he could see the door openings of all the villages in

that countryside quite close together.

And when he came home, he caused these words to be said:

“Let the people come and hear.”

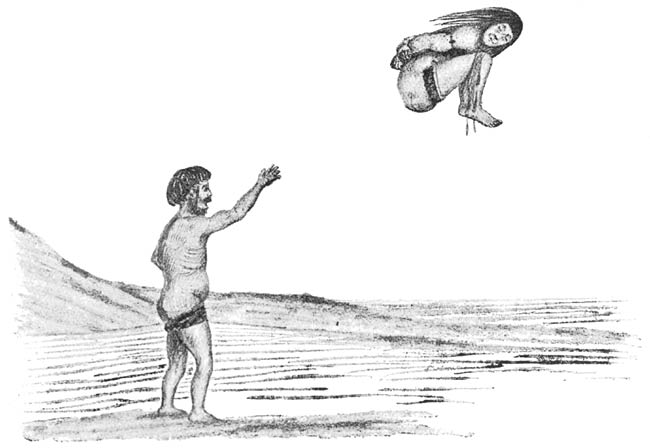

And now many people came hurrying into the house. And he began

calling up spirits. And in this calling he raised himself up and flew

away towards his wife.

And when he came near her in his spirit flight, and hovered above

her, she was sitting sewing. He went straight down through the roof,

and when she tried to escape through the floor he did likewise, and

reached her in the earth. After this, she was very willing when he

tried to take her home with him, and he took her home with him, and now

he had his wife again, and those two people lived together until they

were very old.

One winter, the frost came, and was very hard and the sea was

frozen, and only a little opening was left, far out over the ice. And

hither Qujâvârssuk was forced to carry his kayak each day,

out to the open water, but each day he caught two seals, as was his

custom. [26]

And then, as often happens in time of dearth, there came many poor

people wandering over the ice, from the south, wishing to get some good

thing of all that Qujâvârssuk caught. Once there came also

two old men, and they were his mother’s kinsmen. They came on a

visit. And when they came, his mother said to them:

“Now you have come before I have got anything cooked. It is

true that I have something from the cooking of yesterday; eat that if

you will, while I cook something now.” Then she set before them

the kidney part of a black seal, with its own blubber as dripping. Now

one of the two old men began eating, and went on eagerly, dipping the

meat in the dripping. But the other stopped eating very soon.

Then Qujâvârssuk came home, as was his custom, with two

seals, and said to his mother:

“Take the breast part and boil it quickly.”

For this was the best part of the seal. And she boiled it, and it

was done in a moment. And then she set it on a dish and brought it to

those two.

“Here, eat.”

And now at last the one of them began really to eat, but the other

took a piece of the shoulder. When Qujâvârssuk saw this, he

said:

“You should not begin to eat from the wrong side.”

And when he had said that, he said again:

“If you eat from that side, then my catching of the seals will

cease.” But the old man became very angry in his mind at this

order.

Next morning, when they were about to set off again southward,

Qujâvârssuk’s mother gave them as much meat as they

could carry. They went home southward, over the ice, but when they had

gone a little way, they were forced to stop, because their burden was

so heavy. And when they had rested a little, they went on again. When

they had come near to their village, one said to the other:

“Has there not wakened a thought in your mind? I am very angry

with Qujâvârssuk. Yesterday, when we came there, they gave

us only a kidney piece in welcome, and that is meat I do not like at

all.”

“Hum,” said the other. “I thought it was all very

good. It was fine tender meat for my teeth.”

At these words, the other began again to speak: [27]

“Now that my anger has awakened, I will make a Tupilak for

that miserable Qujâvârssuk.”

But the other said to him:

“Why will you do such a thing? Look; their gifts are so many

that we must carry the load upon our heads.”

But that comrade would not change his purpose, not for all the

trying of the other to turn him from it. And at last the other ceased

to speak of it.

Now as the cold grew stronger, that opening in the ice became

smaller and smaller, at the place where Qujâvârssuk was

used to go with his kayak. One day, when he came down to it, there was

but just room for his kayak to go in, and if now a seal should rise, it

could not fail to strike the kayak. Yet he got into the kayak, and at

the time when he was fixing the head on his harpoon, he saw a black

seal coming up from below. But seeing that it must touch both the ice

and the kayak, it went down again without coming right to the surface.

Then Qujâvârssuk went up again and went home, and that was

the first time he went home without having made a catch, in all the

time he had been a hunter.

When he had come home, he sat himself down behind his mother’s

lamp, sitting on the bedplace, so that only his feet hung down over the

floor. He was so troubled that he would not eat. And later in the

evening, he said to his mother:

“Take meat to Tugto and his wife, and ask one of them to magic

away the ice.”

His mother went out and cut the meat of a black seal across at the

middle. Then she brought the tail half, and half the blubber of a seal,

up to Tugto and his wife. She came to the entrance, but it was covered

with snow, so that it looked like a fox hole. At first, she dropped

that which she was carrying in through the passage way. And it was this

which Tugto and his wife first saw; the half of a black seal’s

meat and half of its blubber cut across. And when she came in, she

said:

“It is my errand now to ask if one of you can magic away the

ice.”

When these words were heard, Tugto said to his wife:

“In this time of hunger we cannot send away meat that is

given. You must magic away the ice.” [28]

And she set about to do his bidding. To

Qujâvârssuk’s mother she said:

“Tell all the people who can come here to come here and

listen!”

And then she began eagerly going in to the dwellings, to say that

all who could come should come in and listen to the magic. When all had

come in, she put out the lamp, and began to call on her helping

spirits. Then suddenly she said:

“Two flames have appeared in the west!”

And now she was standing up in the passage way, and let them come to

her, and when they came forward, they were a bear and a walrus. The

bear blew her in under the bedplace, but when it drew in its breath

again, she came out from under the bedplace and stopped at the passage

way. In this manner it went on for a long time. But now she made ready

to go out, and said then to the listeners:

“All through this night none may yawn or wink an eye.”

And then she went out.

At the same moment when she went out, the bear took her in its teeth

and flung her out over the ice. Hardly had she fallen on the ice again,

when the walrus thrust its tusks into her and flung her out across the

ice, but the bear ran along after her, keeping beneath her as she flew

through the air. Each time she fell on the ice, the walrus thrust its

tusks into her again. It seemed as if the outermost islands suddenly

went to the bottom of the sea, so quickly did she move outwards. They

were now almost out of sight, and not until they could no longer see

the land did the walrus and the bear leave her. Then she could begin

again to go towards the land.

When at last she could see the cliffs, it seemed as if there were

clouds above them, because of the driving snow. At last the wind came

down, and the ice began at once to break up. Now she looked round on

all sides, and caught sight of an iceberg which was frozen fast. And

towards this she let herself drift. Hardly had she come up on to the

iceberg, when the ice all went to pieces, and now there was no way for

her to save herself. But at the same moment she heard someone beside

her say:

“Let me take you in my kayak.” And when she looked

round, she saw a man in a very narrow kayak. And he said a second

time:

“Come and let me take you in my kayak. If you will not do

this, [29]then you will never taste the good things

Qujâvârssuk has paid you.”

Now the sea was very rough, and yet she made ready to go. When a

wave lifted the kayak, she sprang down into it. But as she dropped

down, the kayak was nearly upset. Then, as she tried to move over to

the other side of it, she again moved too far, and then he said:

“Place yourself properly in the middle of the

kayak.”

And when she had done so, he tried to row, for it was his purpose to

take her with him in his kayak, although the sea was very rough. Then

he rowed out with her. And when he had come a little way out, he

sighted land, but when they came near, there was no place at all where

they could come up on shore, and at the moment when the wave took them,

he said:

“Now try to jump ashore.”

And when he said this, she sprang ashore. When she now stood on

land, she turned round and saw that the kayak was lost to sight in a

great wave. And it was never seen again. She turned and went away. But

as she went on, she felt a mighty thirst. She came to a place where

water was oozing through the snow. She went there, and when she reached

it, and was about to lay herself down to drink, a voice came suddenly

and said:

“Do not drink it; for if you do, you will never taste the good

things Qujâvârssuk has paid you.”

When she heard this she went forward again. On her way she came to a

house. On the top of the house lay a great dog, and it was terrible to

see. When she began to go past it, it looked as if it would bite her.

But at last she came past it.

In the passage way of the house there was a great river flowing, and

the only place where she could tread was narrow as the back of a knife.

And the passage way itself was so wide that she could not hold fast by

the walls.

So she walked along, poising carefully, using her little fingers as

wings. But when she came to the inner door, the step was so high, that

she could not come over it quickly. Inside the house, she saw an old

woman lying face downwards on the bedplace. And as soon as she had come

in, the old woman began to abuse her. And she was about to answer those

bad words, when the old woman sprang out on to the floor to fight with

her. And now they two fought furiously [30]together. They fought for a long

time, and little by little the old woman grew tired. And when she was

so tired that she could not get up, the other saw that her hair hung

loose and was full of dirt. And now Tugto’s wife began cleaning

her as well as she could. When this was done, she put up her hair in

its knot. The old woman had not spoken, but now she said:

“You are a dear little thing, you that have come in here. It

is long since I was so nicely cleaned. Not since little Atakana from

Sârdloq cleaned me have I ever been cleaned at all. I have

nothing to give you in return. Move my lamp away.”

And when she did so, there was a noise like the moving of wings.

When she turned to look, she saw a host of birds flying in through the

passage way. For a long time birds flew in, without stopping. But then

the woman said:

“Now it is enough.” And she put the lamp straight. And

when that was done, the other said again:

“Will you not put it a little to the other side?”

And she moved it so. And then she saw some men with long hair flying

towards the passage way. When she looked closer, she saw that it was a

host of black seal. And when very many of them had come in this manner,

she said:

“Now it is enough.” And she put the lamp in its place.

Then the old woman looked over towards her, and said:

“When you come home, tell them that they must never more face

towards the sea when they empty their dirty vessels, for when they do

so, it all goes over me.”

When at last the woman came out again, the big dog wagged his tail

kindly at her.

It was still night when Tugto’s wife came home, and when she

came in, none of them had yet yawned or winked an eye. When she lit the

lamp, her face was fearfully scratched, and she told them this:

“You must not think that the ice will break up at once; it

will not break up until these sores are healed.”

After a long time they began to heal slowly, and sometimes it might

happen that one or another cried in mockingly through the window:

“Now surely it is time the ice broke up and went out to sea,

for that which was to be done is surely done.” [31]

But at last her sores were healed. And one day a black cloud came up

in the south. Later in the evening, there was a mighty noise of the

wind, and the storm did not abate until it was growing light in the

morning. When it was quite light, and the people came out, the sea was

open and blue. A great number of birds were flying above the water, and

there were hosts of black seal everywhere. The kayaks were made ready

at once, and when they began to make them ready, Tugto’s wife

said:

“No one must hunt them yet; until five days are gone no one

may hunt them.”

But before those days were gone, one of the young men went out

nevertheless to hunt. He tried with great efforts, but caught nothing

after all. Not until those days were gone did the witch-wife say:

“Now you may hunt them.”

And now the men went out to sea to hunt the birds. And not until

they could bear no more on their kayaks did they row home again. But

then all those men had to give up their whole catch to Tugto’s

house. Not until the second hunting were they permitted to keep any for

themselves.

Next day they went out to hunt for seal. They harpooned many, but

these also were given to Tugto and his wife. Of these also they kept

nothing for themselves until the second hunting.

Now when the ice was gone, then that old man we have told about

before, he put life into the Tupilak, and said to it then:

“Go out now, and eat up Qujâvârssuk.”

The Tupilak paddled out after him, but Qujâvârssuk had

already reached the shore, and was about to carry up his kayak on to

the land, with a catch of two seals. Now the Tupilak had no fear but

that next day, when he went out, it would be easy to catch and eat him.

And therefore, when it was no later than dawn, it was waiting outside

his house. When Qujâvârssuk awoke, he got up and went down

to his kayak, and began to make ready for hunting. He put on his long

fur coat, and went down and put the kayak in the water. He lifted one

leg and stepped into the kayak, and this the Tupilak saw, but when he

lifted the other leg to step in with that, he disappeared entirely from

its sight. And all through the day it looked for him in vain. At last

it swam in towards land, but by that time [32]he had already reached home, and

drawn the kayak on shore to carry it up. He had a catch of two seal,

and there lay the Tupilak staring after him.

When it was evening, Qujâvârssuk went to rest. He slept,

and awoke, and got up and made things ready to go out. And at this time

the Tupilak was waiting with a great desire for the moment when he

should put off from land. But when he put on his hunting coat ready to

row out, the Tupilak thought:

“Now we shall see if he disappears again.”

And just as he was getting into his kayak, he disappeared from

sight. And at the end of that day also, Qujâvârssuk came

home again, as was his custom, with a catch of two seal.

Now by this time the Tupilak was fearfully hungry. But a Tupilak can

only eat men, and therefore it now thought thus:

“Next time, I will go up on land and eat him there.”

Then it swam over towards land, and as the shore was level, it moved

swiftly, so as to come well up. But it struck its head on the ground,

so that the pain pierced to its backbone, and when it tried to see what

was there, the shore had changed to a steep cliff, and on the top of

the cliff stood Qujâvârssuk, all easy to see. Again it

tried to swim up on to the land, but only hurt itself the more. And now

it was surprised, and looked in vain for

Qujâvârssuk’s house, for it could not see the house

at all. And it was still lying there and staring up, when it saw that a

great stone was about to fall on it, and hardly had it dived under

water when the stone struck it, and broke a rib. Then it swam out and

looked again towards land, and saw Qujâvârssuk again quite

clearly, and also his house.

Now the Tupilak thought:

“I must try another way. Perhaps it will be better to go

through the earth.”

And when it tried to go through the earth, so much was easy; it only

remained then to come up through the floor of the house. But the floor

of the house was hard, and not to be got through. Therefore it tried

behind the house, and there it was quite soft. It came up there, and

went to the passage way, and there was a big black bird, sitting there

eating something. The Tupilak thought:

“That is a fortunate being, which can sit and eat.”

[33]

Then it tried to get up over the walls at the back part of the

house, by taking hold of the grass in the turf blocks. But when it got

there, the bird’s food was the only thing it saw. Again it tried

to get a little farther, seeing that the bird appeared not to heed it

at all, but then suddenly the bird turned and bit a hole just above its

flipper. And this was very painful, so that the Tupilak floundered

about with pain, and floundered about till it came right out into the

water.

And because of all these happenings, it had now become so angered

that it swam back at once to the man who had made it, in order to eat

him up. And when it came there, he was sitting in his kayak with his

face turned towards the sun, and telling no other thing than of the

Tupilak which he had made. For a long time the Tupilak lay there

beneath him, and looked at him, until there came this thought:

“Why did he make me a Tupilak, when afterwards all the trouble

was to come upon me?”

Then it swam up and attacked the kayak, and the water was coloured

red with blood as it ate him. And having thus found food, the Tupilak

felt well and strong and very cheerful, until at last it began to think

thus:

“All the other Tupilaks will certainly call this a shameful

thing, that I should have killed the one who made me.”

And it was now so troubled with shame at this that it swam far out

into the open sea and was never seen again. And men say that it was

because of shame it did so.

One day the old one said to Qujâvârssuk:

“You are named after a man who died of hunger at

Amerdloq.”

It is told of the people of Amerdloq that they catch nothing but

turbot.

And Qujâvârssuk went to Amerdloq and lived there with an

old man, and while he lived there, he made always the same catch as was

his custom. At last the people of Amerdloq began to say to one

another:

“This must be the first time there have been so many black

seal here in our country; every time he goes hunting he catches two

seal.”

At last one of the big hunters went out hunting with him. They fixed

the heads to their harpoons, and when they had come a little [34]way out from

land, Qujâvârssuk stopped. Then when the other had gone a

little distance from him, he turned, and saw that

Qujâvârssuk had already struck one seal. Then he rowed

towards him, but when he came up, it was already killed. So he left him

again for a little while, and when he turned, Qujâvârssuk

had again struck. Then Qujâvârssuk rowed home. And the

other stayed out the whole day, but did not see a single seal.

When Qujâvârssuk had thus continued as a great hunter,

his mother said to him at last that he should marry. He gave her no

answer, and therefore she began to look about herself for a girl for

him to marry, but it was her wish that the girl might be a great

glutton, so that there might not be too much lost of all that meat. And

she began to ask all the unmarried women to come and visit her. And

because of this there came one day a young woman who was not very

beautiful. And this one she liked very much, for that she was a clever

eater, and having regard to this, she chose her out as the one her son

should marry. One day she said to her son:

“That woman is the one you must have.”

And her son obeyed her, as was his custom.

Every day after their marriage, the strongest man in Amerdloq called

in at the window:

“Qujâvârssuk! Let us see which of us can first get

a bladder float for hunting the whale.”

Qujâvârssuk made no answer, as was his custom, but the

old man said to him:

“We use only speckled skin for whales. And they are now at

this time in the mouth of the river.”

After this, they went to rest.

Qujâvârssuk slept, and awoke, and got up, and went away

to the north. And when he had gone a little way to the north, he came

to the mouth of a small fjord. He looked round and saw a speckled seal

that had come up to breathe. When it went down again, he rowed up on

the landward side of it, and fixed the head and line to his harpoon.

When it came up again to breathe, he rowed to where it was, and

harpooned it, and after this, he at once rowed home with it.

The old man made the skin ready, and hung it up behind the house.

But while it was hanging there, there came very often a noise [35]as from the

bladder float, and this although there was no one there. This thing the

old man did not like at all.

When the winter was coming near, the old man said one day to

Qujâvârssuk:

“Now that time will soon be here when the whales come in to

the coast.”

One night Qujâvârssuk had gone out of the house, when he

heard a sound of deep breathing from the west, and this came nearer.

And because this was the first time he had heard so mighty a breathing,

he went in and told the matter in a little voice to his wife. And he

had hardly told her this, when the old man, whom he had thought asleep,

said:

“What is that you are saying?”

“Mighty breathings which I have heard, and did not know them,

and they do not move from that side where the sun is.” This said

Qujâvârssuk.

The old one put on his boots, and went out, and came in again, and

said:

“It is the breathing of a whale.”

In the morning, before it was yet light, there came a sound of

running, and then one came and called through the window:

“Qujâvârssuk! I was the first who heard the whales

breathing.”

It was the strong man, who wished to surpass him in this.

Qujâvârssuk said nothing, as was his custom, but the old

man said:

“Qujâvârssuk heard that while it was yet

night.” And they heard him laugh and go away.

The strong man had already got out the umiak2 into the water to row out to the

whale. And then Qujâvârssuk came out, and they had already

rowed away when Qujâvârssuk got his boat into the water. He

got it full of water, and drew it up again on to the shore, and turned

the stem in towards land and poured the water out, and for the second

time he drew it down into the water. And not until now did he begin to

look about for rowers. They went out, and when they could see ahead,

the strong man of Amerdloq was already far away. Before he had come up

to where he was, Qujâvârssuk told his rowers to stop and be

still. But they wished to go yet farther, [36]believing that the whale would never

come up to breathe in that place. Therefore he said to them:

“You shall see it when it comes up.”

Hardly had the umiak stopped still, when Qujâvârssuk

began to tremble all over. When he turned round, there was already a

whale quite near, and now his rowers begged him eagerly to steer to

where it was. But Qujâvârssuk now saw such a beast for the

first time in his life. And he said:

“Let us look at it.”

And his rowers had to stay still. When the strong man of Amerdloq

heard the breathing of the whale, he looked round after it, and there

lay the beast like a great rock close beside Qujâvârssuk.

And he called out to him from the place where he was:

“Harpoon it!”

Qujâvârssuk made no answer, but his rowers were now even

more eager than before. When the whale had breathed long enough, it

went down again. Now his rowers wished very much to go farther out,

because it was not likely that it would come up again in that way the

next time. But Qujâvârssuk would not move at all.

The whale stayed a long time under the water, and when it came up

again it was still nearer. Now Qujâvârssuk looked at it

again for a long time, and now his rowers became very angry with him at

last. Not until it seemed that the whale must soon go down again did

Qujâvârssuk say:

“Now row towards it.”

And they rowed towards it, and he harpooned it. And when it now

floundered about in pain and went down, he threw out his bladder float,

and it was not strange that this went under water at once.

And those farther out called to him now and said:

“When a whale is struck it will always swim out to sea. Row

now to the place where it would seem that it must come up.”

But Qujâvârssuk did not answer, and did not move from

the place where he was. Not until they called to him for the third time

did he answer:

“The beasts I have struck move always farther in, towards my

house.”

And now they had just begun laughing at him out there, when [37]they heard a

washing of water closer in to shore, and there it lay, quite like a

tiny fish, turning about in its death struggle. They rowed up to it at

once and made a tow line fast. The strong man rowed up to them, and

when he came to where they were, no one of them was eating. Then he

said:

“Not one of you eating, and here a newly-killed

whale?”

When he said this, Qujâvârssuk answered:

“None may eat of it until my mother has first

eaten.”

But the strong man tried then to take a mouthful, although this had

been said. And when he did so, froth came out of his mouth at once. And

he spat out that mouthful, because it was destroying his mouth.

And they brought that catch home, and

Qujâvârssuk’s mother ate of it, and then at last all

ate of it likewise, and then none had any badness in the mouth from

eating of it. But the strong man sat for a long time the only one of

them all who did not eat, and that because he must wait till his mouth

was well again.

And the strong man of Amerdloq did not catch a whale at all until

after Qujâvârssuk had caught another one.

For a whole year Qujâvârssuk stayed at Amerdloq, and

when it was spring, he went back southward to his home. He came to his

own land, and there at a later time he died.

And that is all. [38]

[Contents]

Kúnigseq

There was once a wizard whose name was Kúnigseq.

One day, when he was about to call on his helping spirits and make a

flight down into the underworld, he gave orders that the floor should

be swilled with salt water, to take off the evil smell which might

otherwise frighten his helping spirits away.

Then he began to call upon his helping spirits, and without moving

his body, began to pass downward through the floor.

And down he went. On his way he came to a reef, which was covered

with weed, and therefore so slippery that none could pass that way. And

as he could not pass, his helping spirit lay down beside him, and by

placing his foot upon the spirit, he was able to pass.

And on he went, and came to a great slope covered with heather. Far

down in the underworld, men say, the land is level, and the hills are

small; there is sun down there, and the sky is also like that which we

see from the earth.

Suddenly he heard one crying: “Here comes

Kúnigseq.”

By the side of a little river he saw some children looking for

greyfish.

And before he had reached the houses of men, he met his mother, who

had gone out to gather berries. When he came up to her, she tried again

and again to kiss him, but his helping spirit thrust her aside.

“He is only here on a visit,” said the spirit.

Then she offered him some berries, and these he was about to put in

his mouth, when the spirit said:

“If you eat of them, you will never return.”

A little after, he caught sight of his dead brother, and then his

mother said:

“Why do you wish to return to earth again? Your kin are here.

And look down on the sea-shore; see the great stores of dried meat.

[39]Many

seal are caught here, and it is a good place to be; there is no snow,

and a beautiful open sea.”

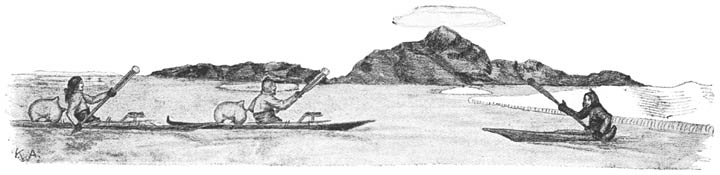

The sea lay smooth, without the slightest wind. Two kayaks were

rowing towards land. Now and again they threw their bird darts, and

they could be heard to laugh.

“I will come again when I die,” said

Kúnigseq.

Some kayaks lay drying on a little island; they were those of men

who had just lost their lives when out in their kayaks.

And it is told that the people of the underworld said to

Kúnigseq:

“When you return to earth, send us some ice, for we thirst for

cold water down here.”

After that, Kúnigseq went back to earth, but it is said that

his son fell sick soon afterwards, and died. And then Kúnigseq

did not care to live any longer, having seen what it was like in the

underworld. So he rowed out in his kayak, and caught a guillemot, and a

little after, he caught a raven, and having eaten these one after the

other, he died. And then they threw him out into the sea. [40]

[Contents]

The Woman Who Had a Bear As a Foster-Son

There was once an old woman living in a place where others lived.

She lived nearest the shore, and when those who lived in houses up

above had been out hunting, they gave her both meat and blubber.

And once they were out hunting as usual, and now and again they got

a bear, so that they frequently ate bear’s meat. And they came

home with a whole bear. The old woman received a piece from the ribs as

her share, and took it home to her house. After she had come home to

her house, the wife of the man who had killed the bear came to the

window and said:

“Dear little old woman in there, would you like to have a

bear’s cub?”

And the old woman went and fetched it, and brought it into her

house, shifted her lamp, and placed the cub, because it was frozen, up

on to the drying frame to thaw. Suddenly she noticed that it moved a

little, and took it down to warm it. Then she roasted some blubber, for

she had heard that bears lived on blubber, and in this way she fed it

from that time onwards, giving it greaves to eat and melted blubber to

drink, and it lay beside her at night.

And after it had begun to lie beside her at night it grew very fast,

and she began to talk to it in human speech, and thus it gained the

mind of a human being, and when it wished to ask its foster-mother for

food, it would sniff.

The old woman now no longer suffered want, and those living near

brought her food for the cub. The children came sometimes to play with

it, but then the old woman would say:

“Little bear, remember to sheathe your claws when you play

with them.”

In the morning, the children would come to the window and call

in:

“Little bear, come out and play with us, for now we are going

to play.” [41]

And when they went out to play together, it would break the

children’s toy harpoons to pieces, but whenever it wanted to give

any one of the children a push, it would always sheathe its claws. But

at last it grew so strong, that it nearly always made the children cry.

And when it had grown so strong the grown-up people began to play with

it, and they helped the old woman in this way, in making the bear grow

stronger. But after a time not even grown men dared play with it, so

great was its strength, and then they said to one another:

“Let us take it with us when we go out hunting. It may help us

to find seal.”

And so one day in the dawn, they came to the old woman’s

window and cried:

“Little bear, come and earn a share of our catch; come out

hunting with us, bear.”

But before the bear went out, it sniffed at the old woman. And then

it went out with the men.

On the way, one of the men said:

“Little bear, you must keep down wind, for if you do not so,

the game will scent you, and take fright.”

One day when they had been out hunting and were returning home, they

called in to the old woman:

“It was very nearly killed by the hunters from the northward;

we hardly managed to save it alive. Give therefore some mark by which

it may be known; a broad collar of plaited sinews about its

neck.”

And so the old foster-mother made a mark for it to wear; a collar of

plaited sinews, as broad as a harpoon line.

And after that it never failed to catch seal, and was stronger even

than the strongest of hunters, and never stayed at home even in the

worst of all weather. Also it was not bigger than an ordinary bear. All

the people in the other villages knew it now, and although they

sometimes came near to catching it, they would always let it go as soon

as they saw its collar.

But now the people from beyond Angmagssalik heard that there was a

bear which could not be caught, and then one of them said:

“If ever I see it, I will kill it.”

But the others said: [42]

“You must not do that; the bear’s foster-mother could

ill manage without its help. If you see it, do not harm it, but leave

it alone, as soon as you see its mark.”

One day when the bear came home as usual from hunting, the old

foster-mother said:

“Whenever you meet with men, treat them as if you were of one

kin with them; never seek to harm them unless they first

attack.”

And it heard the foster-mother’s words and did as she had

said.

And thus the old foster-mother kept the bear with her. In the summer

it went out hunting in the sea, and in winter on the ice, and the other

hunters now learned to know its ways, and received shares of its

catch.

Once during a storm the bear was away hunting as usual, and did not

come home until evening. Then it sniffed at its foster-mother and

sprang up on to the bench, where its place was on the southern side.

Then the old foster-mother went out of the house, and found outside the

body of a dead man, which the bear had hauled home. Then without going

in again, the old woman went hurrying to the nearest house, and cried

at the window:

“Are you all at home?”

“Why?”

“The little bear has come home with a dead man, one whom I do

not know.”

When it grew light, they went out and saw that it was the man from

the north, and they could see he had been running fast, for he had

drawn off his furs, and was in his underbreeches. Afterwards they heard

that it was his comrades who had urged the bear to resistance, because

he would not leave it alone.

A long time after this had happened, the old foster-mother said to

the bear:

“You had better not stay with me here always; you will be

killed if you do, and that would be a pity. You had better leave

me.”

And she wept as she said this. But the bear thrust its muzzle right

down to the floor and wept, so greatly did it grieve to go away from

her.

After this, the foster-mother went out every morning as soon as dawn

appeared, to look at the weather, and if there were but a cloud as big

as one’s hand in the sky, she said nothing. [43]

But one morning when she went out, there was not even a cloud as big

as a hand, and so she came in and said:

“Little bear, now you had better go; you have your own kin far

away out there.”

But when the bear was ready to set out, the old foster-mother,

weeping very much, dipped her hands in oil and smeared them with soot,

and stroked the bear’s side as it took leave of her, but in such

manner that it could not see what she was doing. The bear sniffed at

her and went away. But the old foster-mother wept all through that day,

and her fellows in the place mourned also for the loss of their

bear.

But men say that far to the north, when many bears are abroad, there

will sometimes come a bear as big as an iceberg, with a black spot on

its side.

Here ends this story. [44]

[Contents]

Ímarasugssuaq, Who Ate His Wives

It is said that the great Ímarasugssuaq was wont to eat his

wives. He fattened them up, giving them nothing but salmon to eat, and

nothing at all to drink. Once when he had just lost his wife in the

usual way, he took to wife the sister of many brothers, and her name

was Misána. And after having taken her to wife, he began

fattening her up as usual.

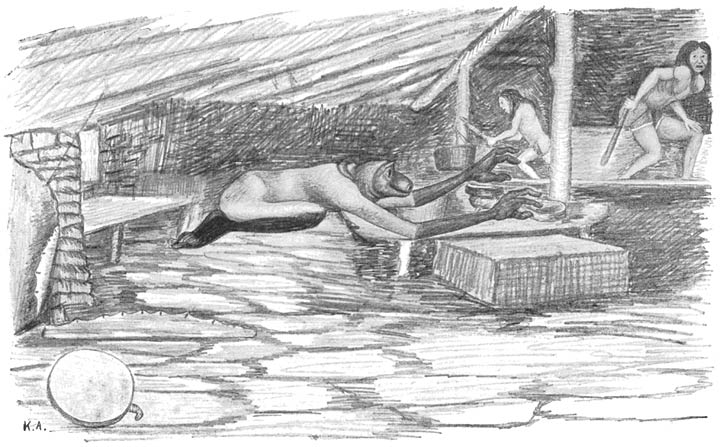

One day her husband was out in his kayak. And she had grown so fat

that she could hardly move, but now she managed with difficulty to

tumble down from the bench to the floor, crawled to the entrance,

dropped down into the passage way, and began licking the snow which had

drifted in. She licked and licked at it, and at last she began to feel

herself lighter, and better able to move. And in this way she

afterwards went out and licked up snow whenever her husband was out in

his kayak, and at last she was once more quite able to move about.

One day when her husband was out in his kayak as usual, she took her

breeches and tunic, and stuffed them out until the thing looked like a

real human being, and then she said to them:

“When my husband comes and tells you to come out, answer him

with these words: I cannot move because I am grown so fat. And when he

then comes in and harpoons you, remember then to shriek as if in

pain.”

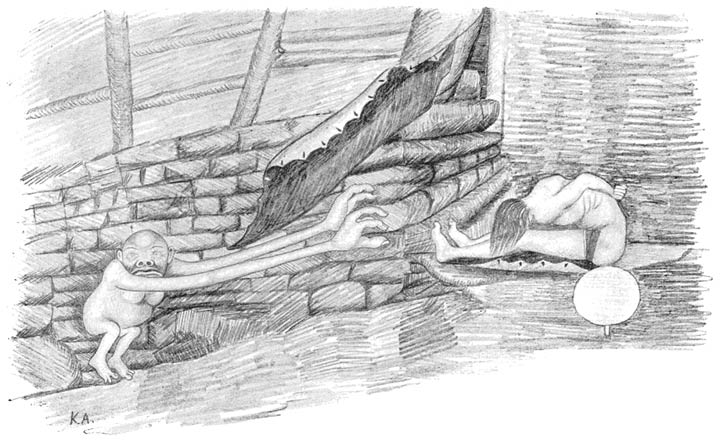

And after she had said these words, she began digging a hole at the

back of the house, and when it was big enough, she crept in.

“Bring up the birds I have caught!”

But the dummy answered:

“I can no longer move, for I am grown so fat.”

Now the dummy was sitting behind the lamp. And the husband coming

in, harpooned that dummy wife with his great bird-spear. And the thing

shrieked as if with pain and fell down. But when he looked [45]closer, there was no

blood to be seen, nothing but some stuffed-out clothes. And where was

his wife?

And now he began to search for her, and as soon as he had gone out,

she crept forth from her hiding-place, and took to flight. And while

she was thus making her escape, her husband came after her, and seeing

that he came nearer and nearer, at last she said:

“Now I remember, my amulet is a piece of wood.”

And hardly had she said these words, when she was changed into a

piece of wood, and her husband could not find her. He looked about as

hard as ever he could, but could see nothing beyond a piece of wood

anywhere. And he stabbed at that once or twice with his knife, but she

felt no more than a little stinging pain. Then he went back home to

fetch his axe, and then, as soon as he was out of sight, she changed

back into a woman again and fled away to her brothers.

When she came to their house, she hid herself behind the skin

hangings, and after she had placed herself there, her husband was heard

approaching, weeping because he had lost his wife. He stayed there with

them, and in the evening, the brothers began singing songs in mockery

of him, and turning towards him also, they said:

“Men say that Ímarasugssuaq eats his wives.”

“Who has said that?”

“Misána has said that.”

“I said it, and I ran away because you tried to kill

me,” said she from behind the hangings.

And then the many brothers fell upon Ímarasugssuaq and held

him fast that his wife might kill him; she took her knife, but each

time she tried to strike, the knife only grazed his skin, for her

fingers lost their power.

And she was still standing there trying in vain to stab him, when

they saw that he was already dead.

Here ends this story. [46]

[Contents]

Qalagánguasê, Who Passed to the Land of

Ghosts

There was once a boy whose name was Qalagánguasê; his

parents lived at a place where the tides were strong. And one day they

ate seaweed, and died of it. Then there was only one sister to look

after Qalagánguasê, but it was not long before she also

died, and then there were only strangers to look after him.

Qalagánguasê was without strength, the lower part of

his body was dead, and one day when the others had gone out hunting, he

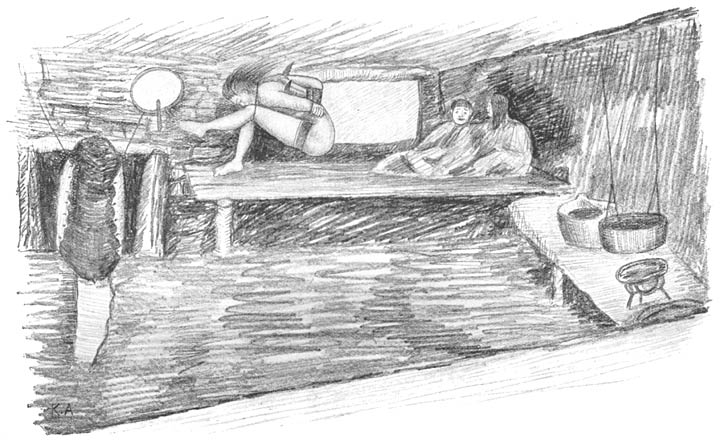

was left alone in the house. He was sitting there quite alone, when

suddenly he heard a sound. Now he was afraid, and with great pains he

managed to drag himself out of the house into the one beside it, and

here he found a hiding-place behind the skin hangings. And while he was

in hiding there, he heard a noise again, and in walked a ghost.

“Ai! There are people here!”

The ghost went over to the water tub and drank, emptying the dipper

twice.

“Thanks for the drink which I thirsty one received,”

said the ghost. “Thus I was wont to drink when I lived on

earth.” And then it went out.

Now the boy heard his fellow-villagers coming up and gathering

outside the house, and then they began to crawl in through the passage

way.

“Qalagánguasê is not here,” they said, when

they came inside.

“Yes, he is,” said the boy. “I hid in here because

a ghost came in. It drank from the water tub there.”

And when they went to look at the water tub, they saw that something

had been drinking from it.

Then some time after, it happened again that the people were all out

hunting, and Qalagánguasê alone in the place. And there

[47]he sat

in the house all alone, when suddenly the walls and frame of the house

began to shake, and next moment a crowd of ghosts came tumbling into

the house, one after the other, and the last was one whom he knew, for

it was his sister, who had died but a little time before.

And now the ghosts sat about on the floor and began playing; they

wrestled, and told stories, and laughed all the time.

At first Qalagánguasê was afraid of them, but at last

he found it a pleasant thing to make the night pass. And not until the

villagers could be heard returning did they hasten away.

“Now mind you do not tell tales,” said the ghost,

“for if you do as we say, then you will gain strength again, and

there will be nothing you cannot do.” And one by one they tumbled

out of the passage way. Only Qalagánguasê’s sister

could hardly get out, and that was because her brother had been minding

her little child, and his touch stayed her. And the hunters were coming

back, and quite close, when she slipped out. One could just see the

shadow of a pair of feet.

“What was that,” said one. “It looked like a pair

of feet vanishing away.”

“Listen, and I will tell you,” said

Qalagánguasê, who already felt his strength returning.

“The house has been full of people, and they made the night pass

pleasantly for me, and now, they say, I am to grow strong

again.”

But hardly had the boy said these words, when the strength slowly

began to leave him.

“Qalagánguasê is to be challenged to a singing

contest,” he heard them say, as he lay there. And then they tied

the boy to the frame post and let him swing backwards and forwards, as

he tried to beat the drum. After that, they all made ready, and set out

for their singing contest, and left the lame boy behind in the house

all alone. And there he lay all alone, when his mother, who had died

long since, came in with his father.

“Why are you here alone?” they asked.

“I am lame,” said the boy, “and when the others went

off to a singing contest, they left me behind.”

“Come away with us,” said his father and mother.

“It is better so, perhaps,” said the boy. [48]

And so they led him out, and bore him away to the land of ghosts,

and so Qalagánguasê became a ghost.

And it is said that Qalagánguasê became a woman when

they changed him to a ghost. But his fellow-villagers never saw him

again. [49]

[Contents]

Isigâligârssik

Isigâligârssik was a wifeless man, and he was very

strong. One of the other men in his village was a wizard.

Isigâligârssik was taken to live in a house with many

brothers, and they were very fond of him.

When the wizard was about to call upon his spirits, it was his

custom to call in through the window: “Only the married men may

come and hear.” And when they who were to hear the spirit calling

went out, a little widow and her daughter and

Isigâligârssik always stayed behind together in the house.

Once, when all had gone out to hear the wizard, as was their custom,

these three were thus left alone together. Isigâligârssik

sat by the little lamp on the side bench, at work.

Suddenly he heard the widow’s daughter saying something in her

mother’s ear, and then her mother turned towards him and

said:

“This little girl would like to have you.”

Isigâligârssik would also like to have her, and before

the others of the house had come back, they were man and wife. Thus

when the others of the house had finished and came back,

Isigâligârssik had found a wife, and his house-fellows were

very glad of this.

Next day, as soon as it was dark, one called, as was the custom:

“Let only those who have wives come and hear.” And

Isigâligârssik, who had before had no wife, felt now a

great desire to go and hear this. But as soon as he had come in, the

great wizard said to Isigâligârssik’s wife:

“Come here; here.”

When she had sat down, he told her to take off her shoes, and then

he put them up on the drying frame. Then they made a spirit calling,

and when that was ended, the wizard said to

Isigâligârssik:

“Go away now; you will never have this dear little wife of

yours again.” [50]

And then Isigâligârssik had to go home without a wife.

And Isigâligârssik had to live without a wife. And every

time there was a spirit calling, and he went in, the wizard would

say:

“Ho, what are you doing here, you who have no wife?”

But now anger grew up slowly in him at this, and once when he came

home, he said:

“That wizard in there has mocked me well, but next time he

asks me, I shall know what to answer.”

But the others of the village warned him, and said:

“No, no; you must not answer him. For if you answer him, then

he will kill you.”

But one evening when the bad wizard mocked him as usual

Isigâligârssik said:

“Ho, and what of you who took my wife away?”

Now the wizard stood up at once, and when Isigâligârssik

bent down towards the entrance to creep out, the wizard took a knife,

and stabbed him with a great wound.

Isigâligârssik ran quickly home to his house, and said

to his wife’s mother:

“Go quickly now and take the dress I wore when I was little.1 It is in the

chest there.”

And when she took it out, it was so small that it did not look like

a dress at all, but it was very pretty. And he ordered her then to dip

it in the water bucket. When it was wet, he was able to put it on, and

when the lacing thong at the bottom touched the wound, it was

healed.

Now when his house-fellows came out after the spirit-calling they

thought to find him lying dead outside the entrance. They followed the

blood spoor, and at last he had gone into the house. When they came in,

he had not a single wound, and all were very glad for that he was

healed again. And now he said:

“To-morrow I will go bow-shooting with him.”

Then they slept, and awakened, and Isigâligârssik opened

his little chest and searched it, and took out a bow that was so small

it could hardly be seen in his hands. He strung that bow, and went out,

and said:

[51]

“Come out now and see.” Then they went out, and he went

down to the wizard’s house, and called through the window:

“Big man in there; come out now and let us shoot with the

bow!” And when he had said this, he went and stood by a little

river. When he turned to look round, the wizard was already by the

passage of his house, aiming with his bow.

He said: “Come here.” And then

Isigâligârssik drew up spittle in his mouth and spat

straight down beside his feet.

“Come here,” he said then, to the great wizard. Then he

went over to him, and came nearer and nearer, and stopped just before

him. Now the wizard aimed with his bow towards him, and when he did

this, the house-fellows cried to Isigâligârssik:

“Make yourself small!” And he made himself so small that

only his head could be seen moving backwards and forwards. The wizard

shot and missed. And a second time he shot and missed.

Then Isigâligârssik stood up, and took the arrow, and

broke it across and said:

“Go home; you cannot hit.” And then the wizard went off,

turning many times to look round. At last, when he bent down to get

into his house through the passage way, Isigâligârssik

aimed and shot at him. And they heard only the sound of his fall. The

arrow was very little, and yet for all that it sent him all doubled up

through the entrance, so that he fell down in the passage.

In this way Isigâligârssik won his wife again, and he

lived with her afterwards until death. [52]

[Contents]

The Insects that Wooed a Wifeless Man

There was once a wifeless man.

Yes, that is the way a story always begins.

And it was his custom to run down to the girls whenever he saw them

out playing. And the young girls always ran away from him into their

houses.

And when the time of great hunting set in, and the kayak men lived

in plenty, it always happened that he shamefully overslept himself

every time he had made up his mind to go out hunting. He did not wake

until the sun had gone down, and the hunters began to come in with

their catch in tow.

One day when he awoke as usual about sunset, he got into his kayak

all the same, and rowed off. Hardly had he passed out of sight of the

houses, when he heard a man crying:

“My kayak has upset, help me.”

And he rowed over and righted him again, and then he saw that it was

one of the Noseless Ones, the people from beneath the earth.

“Now I will give you all my hide thongs with ornaments of

walrus tusk,” said the man who had upset.

“No,” said the wifeless man; “such things I am not

fit to receive; the only thing I cannot overcome is my miserable

sleepiness.”

“First come in with me to land,” said the Fire Man. And

they went in together.

When they reached the place, the Noseless One said:

“This is the man who saved my life when I was near to

death.”

“I happened to save you because my course lay athwart your

own,” said the wifeless man. “It is the first time for many

days that I have been out at all in my kayak.”

“One beast and one only you may choose when you are on your

homeward way. And be careful never to tell what you have seen, or it

will go ill with your hunting hereafter.”

[53]

Those were the Fire Man’s words. And then the wifeless man

rowed home.

But when the time for his expected return had come, he was nowhere

to be seen, and the young girls began to rejoice at the misfortune

which must have befallen him. For they could not bear the sight of that

man.

But then suddenly he came in sight round the point, and at once all

cried:

“Here comes one who looks like the wifeless man.”

And then all the young unmarried girls ran into their houses.

“And the wifeless man has made a catch,” one cried.

And hardly had the evening begun to fall when the wifeless man went

to rest, and hardly had the light appeared when the wifeless man went

out hunting, long before his fellows. Hardly had the sun appeared in

the sky, when the wifeless man came home with three seals. And his

fellow-hunters were then but just preparing to set out.

Thus the days passed for that wifeless man. Early in the morning he

would go out, and when the sun had only just begun to climb the sky, he

would come home with his catch.

Then the unmarried girls began talking together.

“What has come to our wifeless man,” they said, and

began to vie with one another in seeking his favour.

“Let me, let me,” they cried all together.

And the wifeless man turned towards them, and laughingly chose out

the best in the flock.

And now they lived together, the wifeless man and the girl, and

every day there was freshly caught seal meat to be cut up. At last she

grew weary, and cried:

“Why ever do you catch such a terrible lot?”

“H’m,” said he. “The seals come of

themselves, and I catch them—that is all.”

But she kept on asking him, and so he said at last:

“It was in this way. Once....” But having said thus

much, he ceased, and went to rest. But it was long before he could

sleep. And the sun was just over the houses of the village before he

awoke and set out next day.

That day he caught but one seal. [54]

In the evening, his wife began again asking and asking, and seeing

that she would not desist, at last he said:

“It was in this way. Once ... well, I woke up in the evening,

and rowed out, and heard a man crying for help, because his kayak had

upset. And I rowed up to him and righted him again, and when I looked

at him, it was one of the Noseless Ones.”

”’It was a good thing you were not idling about by the

houses,’ said the Noseless One to me.

”’I had but just got into my kayak,’” said

I.

And thus he told all that had happened to him that day, and from

that time forward he lost his power of hunting, for now his old

sleepiness came over him once more, and he lost all.

At last he had not even skins enough to give his wife for her

clothes, and so she ran away and left him. He set off in chase, but she

escaped through a crevice in the rocks, a narrow place whereby he could

just pass.

Now he lay in wait there, and soon he heard a whispering inside:

“You go out to him.”

And out crawled a blowfly, and said:

“Take me.”

“I will not take you,” said the wifeless man, “for

you pick your food from the muck-heaps.”

The blowfly laughed and crawled back again, and he could hear it

say:

“He will not take me, because I pick my food from the

muck-heaps.”

Then there was more whispering inside.

“Now you go out.”

And out came a fly.

“You may have me,” it said.

“Thanks,” said the wifeless man, “but I do not

care for you at all. You lay your eggs about anyhow, and your eyes are

quite abominably big.”

At this the fly laughed, and went inside with the same message as

before.

Again there was a whispering inside.

“Take me,” said the cranefly. [55]

“No, your legs are too long,” said the wifeless man. And

the cranefly went in again, laughing.

Then out came a centipede.

“Take me.”

“I will not take you,” said the wifeless man, “for

you have far too many legs. Your body clings to the ground with all

those legs, and your eyes are simply nasty.”

And the centipede laughed a cackling laugh and went in again.

They whispered together again in there, and out came a gnat.

“Take me,” said the gnat.

“No thanks, you bite,” said the wifeless man. And the