This paper is also available in free-standing form from Project Gutenberg as e-text 19856. The files are identical except that in the present text a few more typographical errors have been corrected, and some illustrations have been replaced.

Some words in the text have variant spellings that were left unchanged. The main ones are:

nyumu: sometimes hyphenated as nyu-mu

Mashongnavi, Shupaulovi, Sichumovi (names): sometimes written with accents as Mashóngnavi, Shupaúlovi, Sichúmovi

Illustrations have been placed as close as practicable to their discussion in the text. The printed page numbers show the original location. Multi-part Figures are sometimes shown vertically (one drawing above the other) where the original layout was horizontal.

The Map and most site plans are shown as thumbnails linked to larger versions.

| Page. | ||

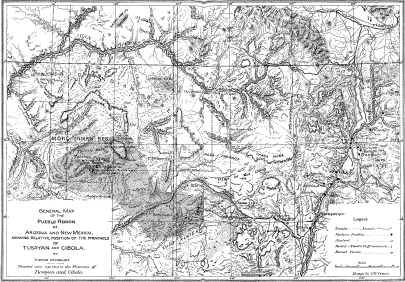

| Plate I. | Map of the provinces of Tusayan and Cibola |

12 |

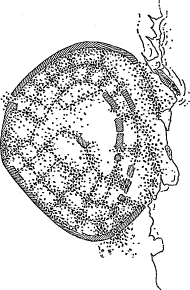

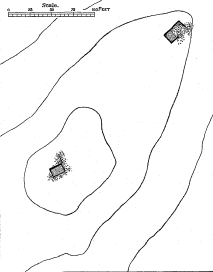

| II. | Old Mashongnavi, plan | 14 |

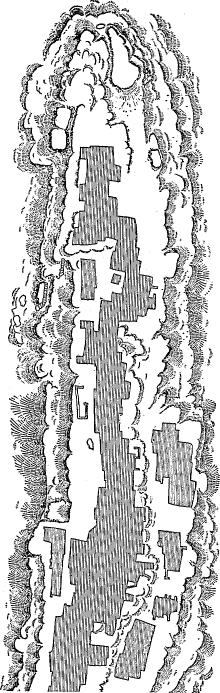

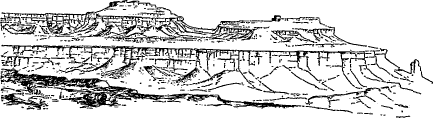

| III. | General view of Awatubi | 16 |

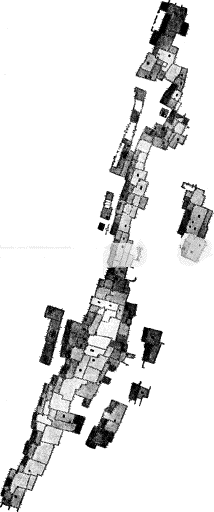

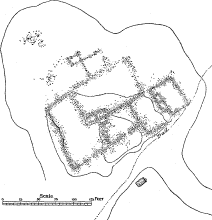

| IV. | Awatubi (Talla-Hogan), plan | 18 |

| V. | Standing walls of Awatubi | 20 |

| VI. | Adobe fragment in Awatubi | 22 |

| VII. | Horn House ruin, plan | 24 |

| VIII. | Bat House | 26 |

| IX. | Mishiptonga (Jeditoh) | 28 |

| X. | A small ruin near Moen-kopi | 30 |

| XI. | Masonry on the outer wall of the Fire-House, detail |

32 |

| XII. | Chukubi, plan | 34 |

| XIII. | Payupki, plan | 36 |

| XIV. | General view of Payupki | 38 |

| XV. | Standing walls of Payupki | 40 |

| XVI. | Plan of Hano | 42 |

| XVII. | View of Hano | 44 |

| XVIII. | Plan of Sichumovi | 46 |

| XIX. | View of Sichumovi | 48 |

| XX. | Plan of Walpi | 50 |

| XXI. | View of Walpi | 52 |

| XXII. | South passageway of Walpi | 54 |

| XXIII. | Houses built over irregular sites, Walpi | 56 |

| XXIV. | Dance rock and kiva, Walpi | 58 |

| XXV. | Foot trail to Walpi | 60 |

| XXVI. | Mashongnavi, plan | 62 |

| XXVII. | Mashongnavi with Shupaulovi in distance | 64 |

| XXVIII. | Back wall of a Mashongnavi house-row | 66 |

| XXIX. | West side of a principal row in Mashongnavi |

68 |

| XXX. | Plan of Shupaulovi | 70 |

| XXXI. | View of Shupaulovi | 72 |

| XXXII. | A covered passageway of Shupaulovi | 74 |

| XXXIII. | The chief kiva of Shupaulovi | 76 |

| XXXIV. | Plan of Shumopavi | 78 |

| XXXV. | View of Shumopavi | 80 |

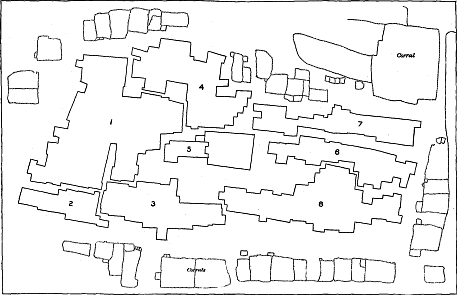

| XXXVI. | Oraibi, plan | In pocket. |

| XXXVII. | Key to the Oraibi plan, also showing localization of gentes |

82 |

| XXXVIII. | A court of Oraibi | 84 |

| XXXIX. | Masonry terraces of Oraibi | 86 |

| XL. | Oraibi house row, showing court side | 88 |

| XLI. | Back of Oraibi house row | 90 |

| XLII. | The site of Moen-kopi | 92 |

| XLIII. | Plan of Moen-kopi | 94 |

| XLIV. | Moen-kopi | 96 |

| 8 XLV. | The Mormon mill at Moen-kopi | 98 |

| XLVI. | Hawikuh, plan | 100 |

| XLVII. | Hawikuh, view | 102 |

| XLVIII. | Adobe church at Hawikuh | 104 |

| XLIX. | Ketchipanan, plan | 106 |

| L. | Ketchipauan | 108 |

| LI. | Stone church at Ketchipauan | 110 |

| LII. | K’iakima, plan | 112 |

| LIII. | Site of K’iakima, at base of Tâaaiyalana | 114 |

| LIV. | Recent wall at K’iakima | 116 |

| LV. | Matsaki, plan | 118 |

| LVI. | Standing wall at Pinawa | 120 |

| LVII. | Halona excavations as seen from Zuñi | 122 |

| LVIII. | Fragments of Halona wall | 124 |

| LIX. | The mesa of Tâaaiyalana, from Zuñi | 126 |

| LX. | Tâaaiyalana, plan | 128 |

| LXI. | Standing walls of Tâaaiyalana ruins | 130 |

| LXII. | Remains of a reservoir on Tâaaiyalana | 132 |

| LXIII. | Kin-tiel, plan (also showing excavations) |

134 |

| LXIV. | North wall of Kin-tiel | 136 |

| LXV. | Standing walls of Kin-tiel | 138 |

| LXVI. | Kinna-Zinde | 140 |

| LXVII. | Nutria, plan | 142 |

| LXVIII. | Nutria, view | 144 |

| LXIX. | Pescado, plan | 146 |

| LXX. | Court view of Pescado, showing corrals | 148 |

| LXXI. | Pescado houses | 150 |

| LXXII. | Fragments of ancient masonry in Pescado | 152 |

| LXXIII. | Ojo Caliente, plan | In pocket. |

| LXXIV. | General view of Ojo Caliente | 154 |

| LXXV. | House at Ojo Caliente | 156 |

| LXXVI. | Zuñi, plan | In pocket. |

| LXXVII. | Outline plan of Zuñi, showing distribution of oblique openings |

158 |

| LXXVIII. | General inside view of Zuñi, looking west |

160 |

| LXXIX. | Zuñi terraces | 162 |

| LXXX. | Old adobe church of Zuñi | 164 |

| LXXXI. | Eastern rows of Zuñi | 166 |

| LXXXII. | A Zuñi court | 168 |

| LXXXIII. | A Zuñi small house | 170 |

| LXXXIV. | A house-building at Oraibi | 172 |

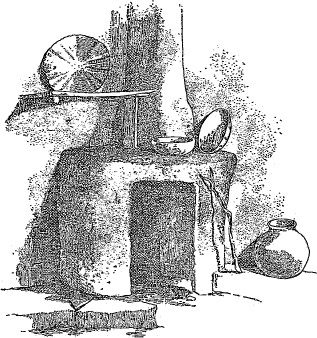

| LXXXV. | A Tusayan interior | 174 |

| LXXXVI. | A Zuñi interior | 176 |

| LXXXVII. | A kiva hatchway of Tusayan | 178 |

| LXXXVIII. | North kivas of Shumopavi, from the northeast |

180 |

| LXXXIX. | Masonry in the north wing of Kin-tiel | 182 |

| XC. | Adobe garden walls near Zuñi. | 184 |

| XCI. | A group of stone corrals near Oraibi | 186 |

| XCII. | An inclosing wall of upright stones at Ojo Caliente |

188 |

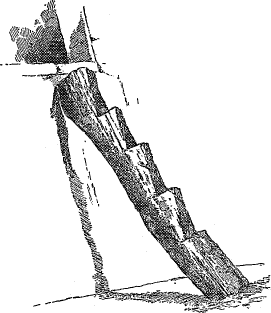

| XCIII. | Upright blocks of sandstone built into an ancient pueblo wall |

190 |

| XCIV. | Ancient wall of upright rocks in southwestern Colorado |

192 |

| XCV. | Ancient floor-beams at Kin-tiel | 194 |

| XCVI. | Adobe walls in Zuñi | 196 |

| XCVII. | Wall coping and oven at Zuñi | 198 |

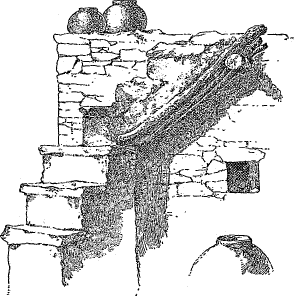

| XCVIII. | Cross-pieces on Zuñi ladders | 200 |

| XCIX. | Outside steps at Pescado | 202 |

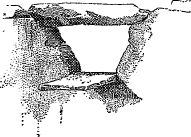

| 9 C. | An excavated room at Kin-tiel | 204 |

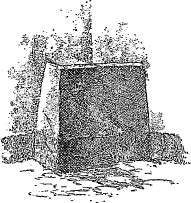

| CI. | Masonry chimneys of Zuñi | 206 |

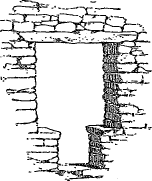

| CII. | Remains of a gateway in Awatubi | 208 |

| CIII. | Ancient gateway, Kin-tiel | 210 |

| CIV. | A covered passageway in Mashongnavi | 212 |

| CV. | Small square openings in Pueblo Bonito | 214 |

| CVI. | Sealed openings in a detached house of Nutria |

216 |

| CVII. | Partial filling-in of a large opening in Oraibi, converting it into a doorway |

218 |

| CVIII. | Large openings reduced to small windows, Oraibi |

220 |

| CIX. | Stone corrals and kiva of Mashongnavi | 222 |

| CX. | Portion of a corral in Pescado | 224 |

| CXI. | Zuñi eagle-cage | 226 |

| Fig. 1. | View of the First Mesa | 43 |

| 2. | Ruins, Old Walpi mound | 47 |

| 3. | Ruin between Bat House and Horn House | 51 |

| 4. | Ruin near Moen-kopi, plan | 53 |

| 5. | Ruin 7 miles north of Oraibi | 55 |

| 6. | Ruin 14 miles north of Oraibi (Kwaituki) | 56 |

| 7. | Oval fire-house ruin, plan. (Tebugkihu) | 58 |

| 8. | Topography of the site of Walpi | 64 |

| 9. | Mashongnavi and Shupaulovi from Shumopavi |

66 |

| 10. | Diagram showing growth of Mashongnavi | 67 |

| 11. | Diagram showing growth of Mashongnavi | 68 |

| 12. | Diagram showing growth of Mashongnavi | 69 |

| 13. | Topography of the site of Shupaulovi | 71 |

| 14. | Court kiva of Shumopavi | 75 |

| 15. | Hampassawan, plan | 84 |

| 16. | Pinawa, plan | 87 |

| 17. | Nutria, plan; small diagram, old wall | 94 |

| 18. | Pescado, plan, old wall diagram | 95 |

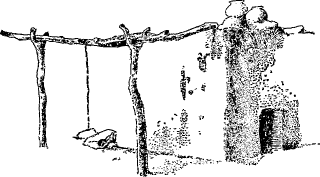

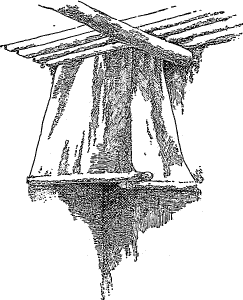

| 19. | A Tusayan wood-rack | 103 |

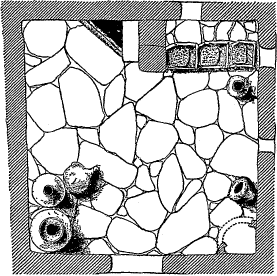

| 20. | Interior ground plan of a Tusayan room | 108 |

| 21. | North kivas of Shumopavi from the southwest |

114 |

| 22. | Ground plan of the chief-kiva of Shupaulovi |

122 |

| 23. | Ceiling-plan of the chief-kiva of Shupaulovi |

123 |

| 24. | Interior view of a Tusayan kiva | 124 |

| 25. | Ground-plan of a Shupaulovi kiva | 125 |

| 26. | Ceiling-plan of a Shupaulovi kiva | 125 |

| 27. | Ground-plan of the chief-kiva of Mashongnavi |

126 |

| 28. | Interior view of a kiva hatchway in Tusayan |

127 |

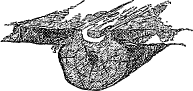

| 29. | Mat used in closing the entrance of Tusayan kivas |

128 |

| 30. | Rectangular sipapuh in a Mashongnavi kiva |

131 |

| 31. | Loom-post in kiva floor at Tusayan | 132 |

| 32. | A Zuñi chimney showing pottery fragments embedded in its adobe base |

139 |

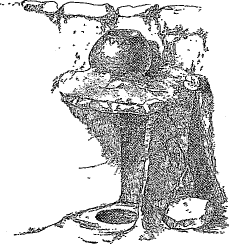

| 33. | A Zuñi oven with pottery scales embedded in its surface |

139 |

| 34. | Stone wedges of Zuñi masonry exposed in a rain-washed wall |

141 |

| 35. | An unplastered house wall in Ojo Caliente |

142 |

| 36. | Wall decorations in Mashongnavi, executed in pink on a white ground |

146 |

| 37. | Diagram of Zuñi roof construction | 149 |

| 38. | Showing abutment of smaller roof-beams over round girders |

151 |

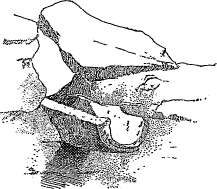

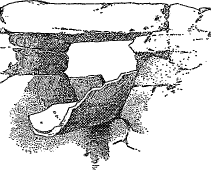

| 39. | Single stone roof-drains | 153 |

| 40. | Trough roof-drains of stone | 153 |

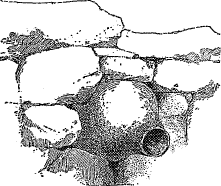

| 10 41. | Wooden roof-drains | 154 |

| 42. | Curved roof-drains of stone in Tusayan | 154 |

| 43. | Tusayan roof-drains; a discarded metate and a gourd |

155 |

| 44. | Zuñi roof-drain, with splash-stones on roof below |

156 |

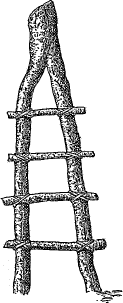

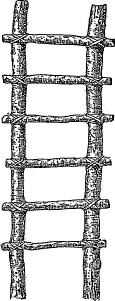

| 45. | A modern notched ladder in Oraibi | 157 |

| 46. | Tusayan notched ladders from Mashongnavi | 157 |

| 47. | Aboriginal American forms of ladder | 158 |

| 48. | Stone steps at Oraibi with platform at corner |

161 |

| 49. | Stone steps, with platform at chimney, in Oraibi |

161 |

| 50. | Stone steps in Shumopavi | 162 |

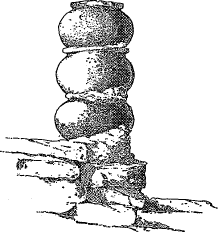

| 51. | A series of cooking pits in Mashongnavi | 163 |

| 52. | Pi-gummi ovens of Mashongnavi | 163 |

| 53. | Cross sections of pi-gummi ovens of Mashongnavi |

163 |

| 54. | Diagrams showing foundation stones of a Zuñi oven |

164 |

| 55. | Dome-shaped oven on a plinth of masonry | 165 |

| 56. | Oven in Pescado exposing stones of masonry |

166 |

| 57. | Oven in Pescado exposing stones of masonry |

166 |

| 58. | Shrines in Mashongnavi | 167 |

| 59. | A poultry house in Sichumovi resembling an oven |

167 |

| 60. | Ground-plan of an excavated room in Kin-tiel |

168 |

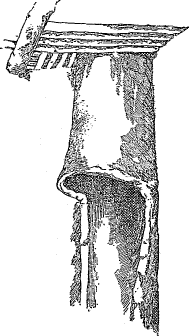

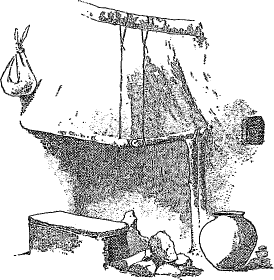

| 61. | A corner chimney-hood with two supporting poles, Tusayan |

170 |

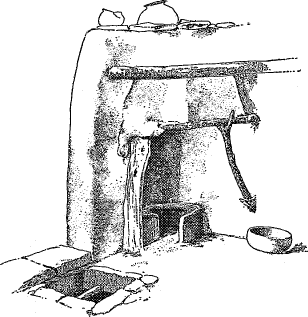

| 62. | A curved chimney-hood of Mashongnavi | 170 |

| 63. | A Mashongnavi chimney-hood and walled-up fireplace |

171 |

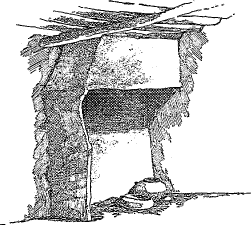

| 64. | A chimney-hood of Shupaulovi | 172 |

| 65. | A semi-detached square chimney-hood of Zuñi |

172 |

| 66. | Unplastered Zuñi chimney-hoods, illustrating construction |

173 |

| 67. | A fireplace and mantel in Sichumovi | 174 |

| 68. | A second-story fireplace in Mashongnavi | 174 |

| 69. | Piki stone and chimney-hood in Sichumovi | 175 |

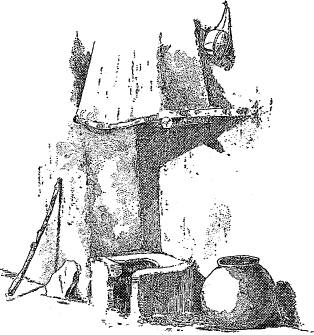

| 70. | Piki stone and primitive andiron in Shumopavi |

176 |

| 71. | A terrace fireplace and chimney of Shumopavi |

177 |

| 72. | A terrace cooking-pit and chimney of Walpi |

177 |

| 73. | A ground cooking-pit of Shumopavi covered with a chimney |

178 |

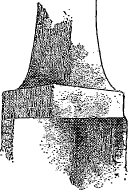

| 74. | Tusayan chimneys | 179 |

| 75. | A barred Zuñi door | 183 |

| 76. | Wooden pivot hinges of a Zuñi door | 184 |

| 77. | Paneled wooden doors in Hano | 185 |

| 78. | Framing of a Zuñi door panel | 186 |

| 79. | Rude transoms over Tusayan openings | 188 |

| 80. | A large Tusayan doorway, with small transom openings |

189 |

| 81. | A doorway and double transom in Walpi | 189 |

| 82. | An ancient doorway in a Canyon de Chelly cliff ruin |

190 |

| 83. | A symmetrical notched doorway in Mashongnavi |

190 |

| 84. | A Tusayan notched doorway | 191 |

| 85. | A large Tusayan doorway with one notched jamb |

192 |

| 86. | An ancient circular doorway, or “stone-close,” in Kin-tiel |

193 |

| 87. | Diagram illustrating symmetrical arrangement of small openings in Pueblo Bonito |

195 |

| 88. | Incised decoration on a rude window-sash in Zuñi |

196 |

| 89. | Sloping selenite window at base of Zuñi wall on upper terrace |

197 |

| 90. | A Zuñi window glazed with selenite | 197 |

| 91. | Small openings in the back wall of a Zuñi house cluster. |

198 |

| 92. | Sealed openings in Tusayan | 199 |

| 93. | A Zuñi doorway converted into a window | 201 |

| 94. | Zuñi roof-openings | 202 |

| 11 95. | A Zuñi roof-opening with raised coping | 203 |

| 96. | Zuñi roof-openings with one raised end | 203 |

| 97. | A Zuñi roof-hole with cover | 204 |

| 98. | Kiva trap-door in Zuñi | 205 |

| 99. | Halved and pinned trap-door frame of a Zuñi kiva |

206 |

| 100. | Typical sections of Zuñi oblique openings |

208 |

| 101. | Arrangement of mealing stones in a Tusayan house |

209 |

| 102. | A Tusayan grain bin | 210 |

| 103. | A Zuñi plume-box | 210 |

| 104. | A Zuñi plume-box | 210 |

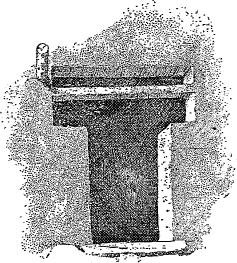

| 105. | A Tusayan mealing trough | 211 |

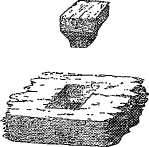

| 106. | An ancient pueblo form of metate | 211 |

| 107. | Zuñi stools | 213 |

| 108. | A Zuñi chair | 213 |

| 109. | Construction of a Zuñi corral | 215 |

| 110. | Gardens of Zuñi | 216 |

| 111. | “Kishoni,” or uncovered shade, of Tusayan | 218 |

| 112. | A Tusayan field shelter, from southwest | 219 |

| 113. | A Tusayan field shelter, from northeast | 219 |

| 114. | Diagram showing ideal section of terraces, with Tusayan names |

223 |

full size

Plate I.

General Map of the Pueblo Region

of Arizona and New Mexico,

Showing Relative Position of the Provinces

of Tusayan and Cibola.

by

Victor Mindeleff.

The remains of pueblo architecture are found scattered over thousands of square miles of the arid region of the southwestern plateaus. This vast area includes the drainage of the Rio Pecos on the east and that of the Colorado on the west, and extends from central Utah on the north beyond the limits of the United States southward, in which direction its boundaries are still undefined.

The descendants of those who at various times built these stone villages are few in number and inhabit about thirty pueblos distributed irregularly over parts of the region formerly occupied. Of these the greater number are scattered along the upper course of the Rio Grande and its tributaries in New Mexico; a few of them, comprised within the ancient provinces of Cibola and Tusayan, are located within the drainage of the Little Colorado. From the time of the earliest Spanish expeditions into the country to the present day, a period covering more than three centuries, the former province has been often visited by whites, but the remoteness of Tusayan and the arid and forbidding character of its surroundings have caused its more complete isolation. The architecture of this district exhibits a close adherence to aboriginal practices, still bears the marked impress of its development under the exacting conditions of an arid environment, and is but slowly yielding to the influence of foreign ideas.

The present study of the architecture of Tusayan and Cibola embraces all of the inhabited pueblos of those provinces, and includes a number of the ruins traditionally connected with them. It will be observed by reference to the map that the area embraced in these provinces comprises but a small portion of the vast region over which pueblo culture once extended.

This study is designed to be followed by a similar study of two typical groups of ruins, viz, that of Canyon de Chelly, in northeastern Arizona, and that of the Chaco Canyon, of New Mexico; but it has been necessary for the writer to make occasional reference to these ruins in the present 14 paper, both in the discussion of general arrangement and characteristic ground plans, embodied in Chapters II and III and in the comparison by constructional details treated in Chapter IV, in order to define clearly the relations of the various features of pueblo architecture. They belong to the same pueblo system illustrated by the villages of Tusayan and Cibola, and with the Canyon de Chelly group there is even some trace of traditional connection, as is set forth by Mr. Stephen in Chapter I. The more detailed studies of these ruins, to be published later, together with the material embodied in the present paper, will, it is thought, furnish a record of the principal characteristics of an important type of primitive architecture, which, under the influence of the arid environment of the southwestern plateaus, has developed from the rude lodge into the many-storied house of rectangular rooms. Indications of some of the steps of this development are traceable even in the architecture of the present day.

The pueblo of Zuñi was surveyed by the writer in the autumn of 1881 with a view to procuring the necessary data for the construction of a large-scale model of this pueblo. For this reason the work afforded a record of external features only.

The modern pueblos of Tusayan were similarly surveyed in the following season (1882-’83), the plans being supplemented by photographs, from which many of the illustrations accompanying this paper have been drawn. The ruin of Awatubi was also included in the work of this season.

In the autumn of 1885 many of the ruined pueblos of Tusayan were surveyed and examined. It was during this season’s work that the details of the kiva construction, embodied in the last chapter of this paper, were studied, together with interior details of the dwellings. It was in the latter part of this season that the farming pueblos of Cibola were surveyed and photographed.

The Tusayan farming pueblo of Moen-kopi and a number of the ruins in the province were surveyed and studied in the early part of the season of 1887-’88, the latter portion of which season was principally devoted to an examination of the Chaco ruins in New Mexico.

In the prosecution of the field work above outlined the author has been greatly indebted to the efficient assistance and hearty cooperation of Mr. Cosmos Mindeleff, by whom nearly all the pueblos illustrated, with the exception of Zuñi, have been surveyed and platted.

The plans obtained have involved much careful work with surveying instruments, and have all been so platted as faithfully to record the minute variations from geometric forms which are so characteristic of the pueblo work, but which have usually been ignored in the hastily prepared sketch plans that have at times appeared. In consequence of the necessary omission of just such information in hastily drawn plans, erroneous impressions have been given regarding the degree of skill to which the pueblo peoples had attained in the planning and building of 15 their villages. In the general distribution of the houses, and in the alignment and arrangement of their walls, as indicated in the plans shown in Chapters II and III, an absence of high architectural attainment is found, which is entirely in keeping with the lack of skill apparent in many of the constructional devices shown in Chapter IV.

Plate II. Old Mashongnavi, plan.

In preparing this paper for publication Mr. Cosmos Mindeleff has rendered much assistance in the revision of manuscript, and in the preparation of some of the final drawings of ground plans; on him has also fallen the compilation and arrangement of Mr. A. M. Stephen’s traditionary material from Tusayan, embraced in the first chapter of the paper.

This latter material is of special interest in a study of the pueblos as indicating some of the conditions under which this architectural type was developed, and it appropriately introduces the more purely architectural study by the author.

Such traditions must be used as history with the utmost caution, and only for events that are very recent. Time relations are often hopelessly confused and the narratives are greatly incumbered with mythologic details. But while so barren in definite information, these traditions are of the greatest value, often through their merely incidental allusions, in presenting to our minds a picture of the conditions under which the repeated migrations of the pueblo builders took place.

The development of architecture among the Pueblo Indians was comparatively rapid and is largely attributable to frequent changes, migrations, and movements of the people as described in Mr. Stephen’s account. These changes were due to a variety of causes, such as disease, death, the frequent warfare carried on between different tribes and branches of the builders, and the hostility of outside tribes; but a most potent factor was certainly the inhospitable character of their environment. The disappearance of some venerated spring during an unusually dry season would be taken as a sign of the disfavor of the gods, and, in spite of the massive character of the buildings, would lead to the migration of the people to a more favorable spot. The traditions of the Zuñis, as well as those of the Tusayan, frequently refer to such migrations. At times tribes split up and separate, and again phratries or distant groups meet and band together. It is remarkable that the substantial character of the architecture should persist through such long series of compulsory removals, but while the builders were held together by the necessity for defense against their wilder neighbors or against each other, this strong defensive motive would perpetuate the laborious type of construction. Such conditions would contribute to the rapid development of the building art.

16In this chapter1 is presented a summary of the traditions of the Tusayan, a number of which were collected from old men, from Walpi on the east to Moen-kopi on the west. A tradition varies much with the tribe and the individual; an authoritative statement of the current tradition on any point could be made only with a complete knowledge of all traditions extant. Such knowledge is not possessed by any one man, and the material included in this chapter is presented simply as a summary of the traditions secured.

The material was collected by Mr. A. M. Stephen, of Keam’s Canyon, Arizona, who has enjoyed unusual facilities for the work, having lived for a number of years past in Tusayan and possessed the confidence of the principal priests—a very necessary condition in work of this character. Though far from complete, this summary is a more comprehensive presentation of the traditionary history of these people than has heretofore been published.

The creation myths of the Tusayan differ widely, but none of them designate the region now occupied as the place of their genesis. These people are socially divided into family groups called wi´ngwu, the descendants of sisters, and groups of wi´ngwu tracing descent from the same female ancestor, and having a common totem called my´umu. Each of these totemic groups preserves a creation myth, carrying in its details special reference to themselves; but all of them claim a common origin in the interior of the earth, although the place of emergence to the surface is set in widely separated localities. They all agree in maintaining this to be the fourth plane on which mankind has existed. In the beginning all men lived together in the lowest depths, in a region of darkness and moisture; their bodies were misshaped and horrible, and they suffered great misery, moaning and bewailing continually. Through the intervention of Myúingwa (a vague conception known as the god of the interior) and of Baholikonga (a crested serpent of enormous size, the genius of water), the “old men” obtained a seed from which sprang a magic growth of cane. It penetrated through a crevice 17 in the roof overhead and mankind climbed to a higher plane. A dim light appeared in this stage and vegetation was produced. Another magic growth of cane afforded the means of rising to a still higher plane on which the light was brighter; vegetation was reproduced and the animal kingdom was created. The final ascent to this present, or fourth plane, was effected by similar magic growths and was led by mythic twins, according to some of the myths, by climbing a great pine tree, in others by climbing the cane, Phragmites communis, the alternate leaves of which afforded steps as of a ladder, and in still others it is said to have been a rush, through the interior of which the people passed up to the surface. The twins sang as they pulled the people out, and when their song was ended no more were allowed to come; and hence, many more were left below than were permitted to come above; but the outlet through which mankind came has never been closed, and Myu´ingwa sends through it the germs of all living things. It is still symbolized by the peculiar construction of the hatchway of the kiva and in the designs on the sand altars in these underground chambers, by the unconnected circle painted on pottery and by devices on basketry and other textile fabrics.

Plate III. General view of Awatubi.

All the people that were permitted to come to the surface were collected and the different families of men were arranged together. This was done under the direction of twins, who are called Pekónghoya, the younger one being distinguished by the term Balíngahoya, the Echo. They were assisted by their grandmother, Kóhkyang wúhti, the Spider woman, and these appear in varying guises in many of the myths and legends. They instructed the people in divers modes of life to dwell on mountain or on plain, to build lodges, or huts, or windbreaks. They distributed appropriate gifts among them and assigned each a pathway, and so the various families of mankind were dispersed over the earth’s surface.

The Hopituh,2 after being taught to build stone houses, were also divided, and the different divisions took separate paths. The legends indicate a long period of extensive migrations in separate communities; the groups came to Tusayan at different times and from different directions, but the people of all the villages concur in designating the Snake people as the first occupants of the region. The eldest member of that nyumu tells a curious legend of their migration from which the following is quoted:

At the general dispersal my people lived in snake skins, each family occupying a separate snake skin bag, and all were hung on the end of a rainbow, which swung around until the end touched Navajo Mountain, where the bags dropped from it; and wherever a bag dropped, there was their house. After they arranged their bags they came out from them as men and women, and they then, built a stone house which had five sides. [The story here relates the adventures of a mythic Snake Youth, who brought back a strange woman who gave birth to rattlesnakes; these bit the people and compelled them to migrate.] A brilliant star arose in the southeast, 18 which would shine for a while and then disappear. The old men said, “Beneath that star there must be people,” so they determined to travel toward it. They cut a staff and set it in the ground and watched till the star reached its top, then they started and traveled as long as the star shone; when it disappeared they halted. But the star did not shine every night, for sometimes many years elapsed before it appeared again. When this occurred, our people built houses during their halt; they built both round and square houses, and all the ruins between here and Navajo Mountain mark the places where our people lived. They waited till the star came to the top of the staff again, then they moved on, but many people were left in those houses and they followed afterward at various times. When our people reached Wipho (a spring a few miles north from Walpi) the star disappeared and has never been seen since. They built a house there and after a time Másauwu (the god of the face of the earth) came and compelled them to move farther down the valley, to a point about half way between the East and Middle Mesa, and there they stayed many plantings. One time the old men were assembled and Másauwu came among them, looking like a horrible skeleton, and his bones rattling dreadfully. He menaced them with awful gestures, and lifted off his fleshless head and thrust it into their faces; but he could not frighten them. So he said, “I have lost my wager; all that I have is yours; ask for anything you want and I will give it to you.” At that time our people’s house was beside the water course, and Másauwu said, “Why are you sitting here in the mud? Go up yonder where it is dry.” So they went across to the low, sandy terrace on the west side of the mesa, near the point, and built a house and lived there. Again the old men were assembled and two demons came among them and the old men took the great Baho and the nwelas and chased them away. When they were returning, and were not far north from their village, they met the Lenbaki (Cane-Flute, a religious society still maintained) of the Horn family. The old men would not allow them to come in until Másauwu appeared and declared them to be good Hopituh. So they built houses adjoining ours and that made a fine, large village. Then other Hopituh came in from time to time, and our people would say, “Build here, or build there,” and portioned the land among the new comers.

The site of the first Snake house in the valley, mentioned in the foregoing legend, is now barely to be discerned, and the people refuse to point out the exact spot. It is held as a place of votive offerings during the ceremony of the Snake dance, and, as its name, Bátni, implies, certain rain-fetiches are deposited there in small jars buried in the ground. The site of the village next occupied can be quite easily distinguished, and is now called Kwetcap tutwi, ash heap terrace, and this was the village to which the name Walpi was first applied—a term meaning the place at the notched mesa, in allusion to a broad gap in the stratum of sandstone on the summit of the mesa, and by which it can be distinguished from a great distance. The ground plan of this early Walpi can still be partly traced, indicating the former existence of an extensive village of clustering, little-roomed houses, with thick walls constructed of small stones.

The advent of the Lenbaki is still commemorated by a biennial ceremony, and is celebrated on the year alternating with their other biennial ceremony, the Snake dance.

The Horn people, to which the Lenbaki belonged, have a legend of coming from a mountain range in the east.

Its peaks were always snow covered, and the trees were always green. From the hillside the plains were seen, over which roamed the deer, the antelope, and the 19 bison, feeding on never-failing grasses. Twining through these plains were streams of bright water, beautiful to look upon. A place where none but those who were of our people ever gained access.

This description suggests some region of the head-waters of the Rio Grande. Like the Snake people, they tell of a protracted migration, not of continuous travel, for they remained for many seasons in one place, where they would plant and build permanent houses. One of these halting places is described as a canyon with high, steep walls, in which was a flowing stream; this, it is said, was the Tségi (the Navajo name for Canyon de Chelly). Here they built a large house in a cavernous recess, high up in the canyon wall. They tell of devoting two years3 to ladder making and cutting and pecking shallow holes up the steep rocky side by which to mount to the cavern, and three years more were employed in building the house. While this work was in progress part of the men were planting gardens, and the women and children were gathering stones. But no adequate reason is given for thus toiling to fit this impracticable site for occupation; the footprints of Másauwu, which they were following, led them there.

The legend goes on to tell that after they had lived there for a long time a stranger happened to stray in their vicinity, who proved to be a Hopituh, and said that he lived in the south. After some stay he left and was accompanied by a party of the “Horn,” who were to visit the land occupied by their kindred Hopituh and return with an account of them; but they never came back. After waiting a long time another band was sent, who returned and said that the first emissaries had found wives and had built houses on the brink of a beautiful canyon, not far from the other Hopituh dwellings. After this many of the Horns grew dissatisfied with their cavern home, dissensions arose, they left their home, and finally they reached Tusayan. They lived at first in one of the canyons east of the villages, in the vicinity of Keam’s Canyon, and some of the numerous ruins on its brink mark the sites of their early houses. There seems to be no legend distinctly attaching any particular ruin to the Horn people, although there is little doubt that the Snake and the Horn were the two first peoples who came to the neighborhood of the present villages. The Bear people were the next, but they arrived as separate branches, and from opposite directions, although of the same Hopituh stock. It has been impossible to obtain directly the legend of the Bears from the west. The story of the Bears from the east tells of encountering the Fire people, then living about 25 miles east from Walpi; but these are now extinct, and nearly all that is known of them is told in the Bear legend, the gist of which is as follows:

The Bears originally lived among the mountains of the east, not far distant from the Horns. Continual quarrels with neighboring villages 20 brought on actual fighting, and the Bears left that region and traveled westward. As with all the other people, they halted, built houses, and planted, remaining stationary for a long while; this occurred at different places along their route.

A portion of these people had wings, and they flew in advance to survey the land, and when the main body were traversing an arid region they found water for them. Another portion had claws with which they dug edible roots, and they could also use them for scratching hand and foot holes in the face of a steep cliff. Others had hoofs, and these carried the heaviest burdens; and some had balls of magic spider web, which they could use on occasion for ropes, and they could also spread the web and use it as a mantle, rendering the wearer invisible when he apprehended danger.

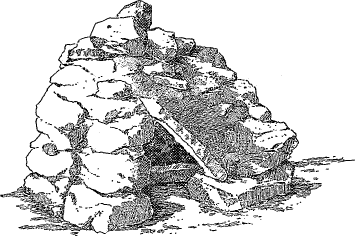

They too came to the Tségi (Canyon de Chelly), where they found houses but no people, and they also built houses there. While living there a rupture occurred, a portion of them separating and going far to the westward. These seceding bands are probably that branch of the Bears who claim their origin in the west. Some time after this, but how long after is not known, a plague visited the canyon, and the greater portion of the people moved away, but leaving numbers who chose to remain. They crossed the Chinli valley and halted for a short time at a place a short distance northeast from Great Willow water (“Eighteen Mile Spring”). They did not remain there long, however, but moved a few miles farther west, to a place occupied by the Fire people who lived in a large oval house. The ruin of this house still stands, the walls from 5 to 8 feet high, and remarkable from the large-sized blocks of stone used in their construction; it is still known to the Hopituh as Tebvwúki, the Fire-house. Here some fighting occurred, and the Bears moved westward again to the head of Antelope (Jeditoh) Canyon, about 4 miles from Keam’s Canyon and about 15 miles east from Walpi. They built there a rambling cluster of small-roomed houses, of which the ground plan has now become almost obliterated. This ruin is called by the Hopituh “the ruin at the place of wild gourds.” They seem to have occupied this neighborhood for a considerable period, as mention is made of two or three segregations, when groups of families moved a few miles away and built similar house clusters on the brink of that canyon.

The Fire-people, who, some say, were of the Horn people, must have abandoned their dwelling at the Oval House or must have been driven out at the time of their conflict with the Bears, and seem to have traveled directly to the neighborhood of Walpi. The Snakes allotted them a place to build in the valley on the east side of the mesa, and about two miles north from the gap. A ridge of rocky knolls and sand dunes lies at the foot of the mesa here, and close to the main cliff is a spring. There are two prominent knolls about 400 yards apart and the summits of these are covered with traces of house walls; also portions of walls can be discerned on all the intervening hummocks. The place is known as Sikyátki, 21 the yellow-house, from the color of the sandstone of which the houses were built. These and other fragmentary bits have walls not over a foot thick, built of small stones dressed by rubbing, and all laid in mud; the inside of the walls also show a smooth coating of mud plaster. The dimensions of the rooms are very small, the largest measuring 9½ feet long, by 4½ feet wide. It is improbable that any of these structures were over two stories high, and many of them were built in excavated places around the rocky summits of the knolls. In these instances no rear wall was built; the partition walls, radiating at irregular angles, abut against the rock itself. Still, the great numbers of these houses, small as they were, must have been far more than the Fire-people could have required, for the oval house which they abandoned measures not more than a hundred feet by fifty. Probably other incoming gentes, of whom no story has been preserved, had also the ill fate to build there, for the Walpi people afterward slew all its inhabitants.

There is little or no detail in the legends of the Bear people as to their life in Antelope Canyon; they can now distinguish only one ruin with certainty as having been occupied by their ancestors, while to all the other ruins fanciful names have been applied. Nor is there any special cause mentioned for abandoning their dwellings there; probably, however, a sufficient reason was the cessation of springs in their vicinity. Traces of former large springs are seen at all of them, but no water flows from them at the present time. Whatever their motive, the Bears left Antelope Canyon, and moved over to the village of Walpi, on the terrace below the point of the mesa. They were received kindly there, and were apparently placed on an equal footing with the Walpi, for it seems the Snake, Horn, and Bear have always been on terms of friendship. They built houses at that village, and lived there for some considerable time; then they moved a short distance and built again almost on the very point of the mesa. This change was not caused by any disagreement with their neighbors; they simply chose that point as a suitable place on which to build all their houses together. The site of this Bear house is called Kisákobi, the obliterated house, and the name is very appropriate, as there is merely the faintest trace here and there to show where a building stood, the stones having been used in the construction of the modern Walpi. These two villages were quite close together, and the subsequent construction of a few additional groups of rooms almost connected them, so that they were always considered and spoken of as one.

It was at this period, while Walpi was still on this lower site, that the Spaniards came into the country. They met with little or no opposition, and their entrance was marked by no great disturbances. No special tradition preserves any of the circumstances of this event; these first coming Spaniards being only spoken of as the “Kast´ilumuh who wore iron garments, and came from the south,” and this brief mention may be accounted for by the fleeting nature of these early visits.

The zeal of the Spanish priests carried them everywhere throughout 22 their newly acquired territory, and some time in the seventeenth century a band of missionary monks found their way to Tusayan. They were accompanied by a few troops to impress the people with a due regard for Spanish authority, but to display the milder side of their mission, they also brought herds of sheep and cattle for distribution. At first these were herded at various springs within a wide radius around the villages, and the names still attaching to these places memorize the introduction of sheep and cattle to this region. The Navajo are first definitely mentioned in tradition as occupants of this vicinity in connection with these flocks and herds, in the distribution of which they gave much undesirable assistance by driving off the larger portion to their own haunts.

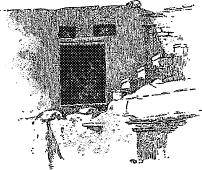

The missionaries selected Awatubi, Walpi, and Shumopavi as the sites for their mission buildings, and at once, it is said, began to introduce a system of enforced labor. The memory of the mission period is held in great detestation, and the onerous toil the priests imposed is still adverted to as the principal grievance. Heavy pine timbers, many of which are now pointed out in the kiva roofs, of from 15 to 20 feet in length and a foot or more in diameter, were cut at the San Francisco Mountain, and gangs of men were compelled to carry and drag them to the building sites, where they were used as house beams. This necessitated prodigious toil, for the distance by trail is a hundred miles, most of the way over a rough and difficult country. The Spaniards are said to have employed a few ox teams in this labor, but the heaviest share was performed by the impressed Hopituh, who were driven in gangs by the Spanish soldiers, and any who refused to work were confined in a prison house and starved into submission.

The “men with the long robes,” as the missionaries were called, are said to have lived among these people for a long time, but no trace of their individuality survives in tradition.

Possibly the Spanish missionaries may have striven to effect some social improvement among these people, and by the adoption of some harsh measures incurred the jealous anger of the chiefs. But the system of labor they enforced was regarded, perhaps justly, as the introduction of serfdom, such as then prevailed in the larger communities in the Rio Grande valleys. Perhaps tradition belies them; but there are many stories of their evil, sensual lives—assertions that they violated women, and held many of the young girls at their mission houses, not as pupils, but as concubines.

In any case, these hapless monks were engaged in a perilous mission in seeking to supplant the primitive faith of the Tusayan, for among the native priests they encountered prejudices even as violent as their own. With too great zeal they prohibited the sacred dances, the votive offerings to the nature-deities, and similar public observances, and strove to suppress the secret rites and abolish the religious orders and societies. But these were too closely incorporated with the system of gentes and 23 other family kinships to admit of their extinction. Traditionally, it is said that, following the discontinuance of the prescribed ceremonies, the favor of the gods was withdrawn, the clouds brought no rain, and the fields yielded no corn. Such a coincidence in this arid region is by no means improbable, and according to the legends, a succession of dry seasons resulting in famine has been of not infrequent occurrence. The superstitious fears of the people were thus aroused, and they cherished a mortal hatred of the monks.

In such mood were they in the summer of 1680, when the village Indians rose in revolt, drove out the Spaniards, and compelled them to retreat to Mexico. There are some dim traditions of that event still existing among the Tusayan, and they tell of one of their own race coming from the river region by the way of Zuñi to obtain their cooperation in the proposed revolt. To this they consented.

Only a few Spaniards being present at that time, the Tusayan found courage to vent their enmity in massacre, and every one of the hated invaders perished on the appointed day. The traditions of the massacre center on the doom of the monks, for they were regarded as the embodiment of all that was evil in Spanish rule, and their pursuit, as they tried to escape among the sand dunes, and the mode of their slaughter, is told with grim precision; they were all overtaken and hacked to pieces with stone tomahawks.

It is told that while the monks were still in authority some of the Snake women urged a withdrawal from Walpi, and, to incite the men to action, carried their mealing-stones and cooking vessels to the summit of the mesa, where they desired the men to build new houses, less accessible to the domineering priests. The men followed them, and two or three small house groups were built near the southwest end of the present village, one of them being still occupied by a Snake family, but the others have been demolished or remodeled. A little farther north, also on the west edge, the small house clusters there were next built by the families of two women called Tji-vwó-wati and Si-kya-tcí-wati. Shortly after the massacre the lower village was entirely abandoned, and the building material carried above to the point which the Snakes had chosen, and on which the modern Walpi was constructed. Several beams of the old mission houses are now pointed out in the roofs of the kivas.

There was a general apprehension that the Spaniards would send a force to punish them, and the Shumopavi also reconstructed their village in a stronger position, on a high mesa overlooking its former site. The other villages were already in secure positions, and all the smaller agricultural settlements were abandoned at this period, and excepting at one or two places on the Moen-kopi, the Tusayan have ever since confined themselves to the close vicinity of their main villages.

The house masses do not appear to bear any relation to division by phratries. It is surprising that even the social division of the phratries 24 is preserved. The Hopituh certainly marry within phratries, and occasionally with the same gens. There is no doubt, however, that in the earlier villages each gens, and where practicable, the whole of the phratry, built their houses together. To a certain extent the house of the priestess of a gens is still regarded as the home of the gens. She has to be consulted concerning proposed marriages, and has much to say in other social arrangements.

While the village of the Walpi was still upon the west side of the mesa point, some of them moved around and built houses beside a spring close to the east side of the mesa. Soon after this a dispute over planting ground arose between them and the Sikyátki, whose village was also on that side of the mesa and but a short distance above them. From this time forward bad blood lay between the Sikyátki and the Walpi, who took up the quarrel of their suburb. It also happened about that time, so tradition says, more of the Coyote people came from the north, and the Pikyás nyu-mu, the young cornstalk, who were the latest of the Water people, came in from the south. The Sikyátki, having acquired their friendship, induced them to build on two mounds, on the summit of the mesa overlooking their village. They had been greatly harrassed by the young slingers and archers of Walpi, who would come across to the edge of the high cliff and assail them with impunity, but the occupation of these two mounds by friends afforded effectual protection to their village. These knolls are about 40 yards apart, and about 40 feet above the level of the mesa which is something over 400 feet above Sikyátki. Their roughly leveled summits measure 20 by 10 feet and are covered with traces of house walls; and it is evident that groups of small-roomed houses were clustered also around the sloping sides. About a hundred yards south from their dwellings the people of the mounds built for their own protection a strong wall entirely across the mesa, which at that point is contracted to about 200 feet in width, with deep vertical cliffs on either side. The base of the wall is still quite distinct, and is about 3 feet thick.

But no reconciliation was ever effected between the Walpi and the Sikyátki and their allies, and in spite of their defensive wall frequent assaults were made upon the latter until they were forced to retreat. The greater number of them retired to Oraibi and the remainder to Sikyátki, and the feud was still maintained between them and the Walpi.

Some of the incidents as well as the disastrous termination of this feud are still narrated. A party of the Sikyátki went prowling through Walpi one day while the men were afield, and among other outrages, one of them shot an arrow through a window and killed a chief’s daughter while she was grinding corn. The chief’s son resolved to avenge the death of his sister, and some time after this went to Sikyátki, professedly to take part in a religious dance, in which he joined until just before the close of the ceremony. Having previously observed where the handsomest girl was seated among the spectators on the house terraces, 25 he ran up the ladder as if to offer her a prayer emblem, but instead he drew out a sharp flint knife from his girdle and cut her throat. He threw the body down where all could see it, and ran along the adjoining terraces till he cleared the village. A little way up the mesa was a large flat rock, upon which he sprang and took off his dancer’s mask so that all might recognize him; then turning again to the mesa he sped swiftly up the trail and escaped.

And so foray and slaughter continued to alternate between them until the planting season of some indefinite year came around. All the Sikyátki men were to begin the season by planting the fields of their chief on a certain day, which was announced from the housetop by the Second Chief as he made his customary evening proclamations, and the Walpi, becoming aware of this, planned a fatal onslaught. Every man and woman able to draw a bow or wield a weapon were got in readiness and at night they crossed the mesa and concealed themselves along its edge, overlooking the doomed village. When the day came they waited until the men had gone to the field and then rushed down upon the houses. The chief, who was too old to go afield, was the first one killed, and then followed the indiscriminate slaughter of women and children, and the destruction of the houses. The wild tumult in the village alarmed the Sikyátki and they came rushing back, but too late to defend their homes. Their struggles were hopeless, for they had only their planting sticks to use as weapons, which availed but little against the Walpi with their bows and arrows, spears, slings, and war clubs. Nearly all of the Sikyátki men were killed, but some of them escaped to Oraibi and some to Awatubi. A number of the girls and younger women were spared, and distributed among the different villages, where they became wives of their despoilers.

It is said to have been shortly after the destruction of Sikyátki that the first serious inroad of a hostile tribe occurred within this region, and all the stories aver that these early hostiles were from the north, the Ute being the first who are mentioned, and after them the Apache, who made an occasional foray.

While these families of Hopituh stock had been building their straggling dwellings along the canyon brinks, and grouping in villages around the base of the East Mesa, other migratory bands of Hopituh had begun to arrive on the Middle Mesa. As already said, it is admitted that the Snake were the first occupants of this region, but beyond that fact the traditions are contradictory and confused. It is probable, however, that not long after the arrival of the Horn, the Squash people came from the south and built a village on the Middle Mesa, the ruin of which is called Chukubi. It is on the edge of the cliff on the east side of the neck of that mesa, and a short distance south of the direct trail leading from Walpi to Oraibi. The Squash people say that they came from Palát Kwabi, the Red Land in the far South, and this vague term expresses nearly all their knowledge of that traditional land. They say they lived 26 for a long time in the valley of the Colorado Chiquito, on the south side of that stream and not far from the point where the railway crosses it. They still distinguish the ruin of their early village there, which was built as usual on the brink of a canyon, and call it Etípsíkya, after a shrub that grows there profusely. They crossed the river opposite that place, but built no permanent houses until they reached the vicinity of Chukubi, near which two smaller clusters of ruins, on knolls, mark the sites of dwellings which they claim to have been theirs. Three groups (nyumu) traveling together were the next to follow them; these were the Bear, the Bear-skin-rope, and the Blue Jay. They are said to have been very numerous, and to have come from the vicinity of San Francisco Mountain. They did not move up to Chukubi, but built a large village on the summit, at the south end of the mesa, close to the site of the present Mashongnavi. Soon afterward came the Burrowing Owl, and the Coyote, from the vicinity of Navajo Mountains in the north, but they were not very numerous. They also built upon the Mashongnavi summit.

After this the Squash people found that the water from their springs was decreasing, and began moving toward the end of the mesa, where the other people were. But as there was then no suitable place left on the summit, they built a village on the sandy terrace close below it, on the west side; and as the springs at Chukubi ultimately ceased entirely, the rest of the Squash people came to the terrace and were again united in one village. Straggling bands of several other groups, both wingwu and nyumu, are mentioned as coming from various directions. Some built on the terrace and some found house room in Mashongnavi. This name is derived as follows: On the south side of the terrace on which the Squash village was built is a high column of sandstone which is vertically split in two, and formerly there was a third pillar in line, which has long since fallen. These three columns were called Tútuwalha, the guardians, and both the Squash village and the one on the summit were so named. On the north side of the terrace, close to the present village, is another irregular massy pillar of sandstone called Mashóniniptu, meaning “the other which remains erect,” having reference to the one on the south side, which had fallen. When the Squash withdrew to the summit the village was then called Mashóniniptuovi, “at the place of the other which remains erect;” now that term is never used, but always its syncopated form, Mashongnavi.

The Squash village, on the south end of the Middle Mesa, was attacked by a fierce band that came from the north, some say the Ute, others say the Apache; but whoever the invaders were, they completely overpowered the people, and carried off great stores of food and other plunder. The village was then evacuated, the houses dismantled, and the material removed to the high summit, where they reconstructed their dwellings around the village which thenceforth bore its present name of Mashongnavi. Some of the Squash people moved over to Oraibi, and portions of the Katchina and Paroquet people came from 27 there to Mashongnavi about the same time, and a few of these two groups occupied some vacant houses also in Shupaulovi; for this village even at that early date had greatly diminished in population, having sustained a disastrous loss of men in the canyon affrays east of Walpi.

Shumopavi seems to have been built by portions of the same groups who went to the adjacent Mashongnavi, but the traditions of the two villages are conflicting. The old traditionists at Shumopavi hold that the first to come there were the Paroquet, the Bear, the Bear-skin-rope, and the Blue Jay. They came from the west—probably from San Francisco Mountain. They claim that ruins on a mesa bluff about 10 miles south from the present village are the remains of a village built by these groups before reaching Shumopavi, and the Paroquets arrived first, it is said, because they were perched on the heads of the Bears, and, when nearing the water, they flew in ahead of the others. These groups built a village on a broken terrace, on the east side of the cliff, and just below the present village. There is a spring close by called after the Shunóhu, a tall red grass, which grew abundantly there, and from which the town took its name. This spring was formerly very large, but two years ago a landslide completely buried it; lately, however, a small outflow is again apparent.

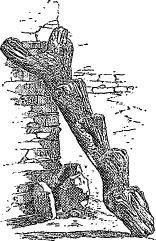

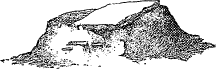

The ruins of the early village cover a hillocky area of about 800 by 250 feet, but it is impossible to trace much of the ground plan with accuracy. The corner of an old house still stands, some 6 or 8 feet high, extending about 15 feet on one face and about 10 feet on the other. The wall is over 3 feet in thickness, but of very clumsy masonry, no care having been exercised in dressing the stones, which are of varying sizes and laid in mud plaster. Interest attaches to this fragment, as it is one of the few tangible evidences left of the Spanish priests who engaged in the fatal mission to the Hopituh in the sixteenth century. This bit of wall, which now forms part of a sheep-fold, is pointed out as the remains of one of the mission buildings.

Other groups followed—the Mole, the Spider, and the “Wíksrun.” These latter took their name from a curious ornament worn by the men. A piece of the leg-bone of a bear, from which the marrow had been extracted and a stopper fixed in one end, was attached to the fillet binding the hair, and hung down in front of the forehead. This gens and the Mole are now extinct.

Shumopavi received no further accession of population, but lost to some extent by a portion of the Bear people moving across to Walpi. No important event seems to have occurred among them for a long period after the destruction of Sikyátki, in which they bore some part, and only cursory mention is made of the ingress of “enemies from the north;” but their village, apparently, was not assailed.

The Oraibi traditions tend to confirm those of Shumopavi, and tell that the first houses there were built by Bears, who came from the latter place. The following is from a curious legend of the early settlement:

28 The Bear people had two chiefs, who were brothers; the elder was called Vwen-ti-só-mo, and the younger Ma-tcí-to. They had a desperate quarrel at Shumopavi, and their people divided into two factions, according as they inclined to one or other of the contestants. After a long period of contention Ma-tcí-to and his followers withdrew to the mesa where Oraibi now stands, about 8 miles northwest from Shumopavi, and built houses a little to the southwest of the limits of the present town. These houses were afterwards destroyed by “enemies from the north,” and the older portion of the existing town, the southwest ends of the house rows, were built with stones from the demolished houses. Fragments of these early walls are still occasionally unearthed.

After Ma-tcí-to and his people were established there, whenever any of the Shumopavi people became dissatisfied with that place they built at Oraibi, Ma-tcí-to placed a little stone monument about halfway between these two villages to mark the boundary of the land. Vwenti-so´-mo objected to this, but it was ultimately accepted with the proviso that the village growing the fastest should have the privilege of moving it toward the other village. The monument still stands, and is on the direct Oraibi trail from Shumopavi, 3 miles from the latter. It is a well dressed, rectangular block of sandstone, projecting two feet above the ground, and measures 8½ by 7 inches. On the end is carved the rude semblance of a human head, or mask, the eyes and mouth being merely round shallow holes, with a black line painted around them. The stone is pecked on the side, but the head and front are rubbed quite smooth, and the block, tapering slightly to the base, suggests the ancient Roman Termini.

There are Eagle people living at Oraibi, Mashongnavi, and Walpi, and it would seem as if they had journeyed for some time with the later Snake people and others from the northwest. Vague traditions attach them to several of the ruins north of the Moen-kopi, although most of these are regarded as the remains of Snake dwellings.

The legend of the Eagle people introduces them from the west, coming in by way of the Moen-kopi water course. They found many people living in Tusayan, at Oraibi, the Middle Mesa, and near the East Mesa, but the Snake village was yet in the valley. Some of the Eagles remained at Oraibi, but the main body moved to a large mound just east of Mashongnavi, on the summit of which they built a village and called it Shi-tái-mu. Numerous traces of small-roomed houses can be seen on this mound and on some of the lower surroundings. The uneven summit is about 300 by 200 feet, and the village seems to have been built in the form of an irregular ellipse, but the ground plan is very obscure.

While the Eagles were living at Shi-tái-mu, they sent “Yellow Foot” to the mountain in the east (at the headwaters of the Rio Grande) to obtain a dog. After many perilous adventures in caverns guarded by bear, mountain lion, and rattlesnake, he got two dogs and returned. 29 They were wanted to keep the coyotes out of the corn and the gardens. The dogs grew numerous, and would go to Mashongnavi in search of food, and also to some of the people of that village, which led to serious quarrels between them and the Eagle people. Ultimately the Shi-tái-mu chief proclaimed a feast, and told the people to prepare to leave the village forever. On the feast day the women arranged the food basins on the ground in a long line leading out of the village. The people passed along this line, tasting a mouthful here or there, but without stopping, and when they reached the last basin they were beyond the limits of the village. Without turning around they continued on down into the valley until they were halted by the Snake people. An arrangement was effected with the latter, and the Eagles built their houses in the Snake village. A few of the Eagle families who had become attached to Mashongnavi chose to go to that village, where their descendants still reside, and are yet held as close relatives by the Eagles of Walpi. The land around the East Mesa was then portioned out, the Snakes, Horns, Bears, and Eagles each receiving separate lands, and these old allotments are still approximately maintained.

According to the Eagle traditions the early occupants of Tusayan came in the following succession: Snake, Horn, Bear, Middle Mesa, Oraibi, and Eagle, and finally from the south came the Water families. This sequence is also recognized in the general tenor of the legends of the other groups.

Shupaulovi, a small village quite close to Mashongnavi, would seem to have been established just before the coming of the Water people. Nor does there seem to have been any very long interval between the arrival of the earliest occupants of the Middle Mesa and this latest colony. These were the Sun people, and like the Squash folk, claim to have come from Palátkwabi, the Red Land, in the south. On their northward migration, when they came to the valley of the Colorado Chiquito, they found the Water people there, with whom they lived for some time. This combined village was built upon Homólobi, a round terraced mound near Sunset Crossing, where fragmentary ruins covering a wide area can yet be traced.

Incoming people from the east had built the large village of Awatubi, high rock, upon a steep mesa about nine miles southeast from Walpi. When the Sun people came into Tusayan they halted at that village and a few of them remained there permanently, but the others continued west to the Middle Mesa. At that time also they say Chukubi, Shitaimu, Mashongnavi, and the Squash village on the terrace were all occupied, and they built on the terrace close to the Squash village also. The Sun people were then very numerous and soon spread their dwellings over the summit where the ruin now stands, and many indistinct lines of house walls around this dilapidated village attest its former size. Like the neighboring village, it takes its name from a rock near by, 30 which is used as a place for the deposit of votive offerings, but the etymology of the term can not be traced.

Some of the Bear people also took up their abode at Shupaulovi, and later a nyumu of the Water family called Batni, moisture, built with them; and the diminished families of the existing village are still composed entirely of these three nyumu.

The next arrivals seem to have been the Asanyumu, who in early days lived in the region of the Chama, in New Mexico, at a village called Kaékibi, near the place now known as Abiquiu. When they left that region they moved slowly westward to a place called Túwii (Santo Domingo), where some of them are said to still reside. The next halt was at Kaiwáika (Laguna) where it is said some families still remain, and they staid also a short time at A´ikoka (Acoma); but none of them remained at that place. From the latter place they went to Sióki (Zuñi), where they remained a long time and left a number of their people there, who are now called Aiyáhokwi by the Zuñi. They finally reached Tusayan by way of Awatubi. They had been preceded from the same part of New Mexico by the Honan nyumu (the Badger people), whom they found living at the last-named village. The Magpie, the Pute Kóhu (Boomerang-shaped hunting stick), and the Field-mouse families of the Asa remained and built beside the Badger, but the rest of its groups continued across to the Walpi Mesa. They were not at first permitted to come up to Walpi, which then occupied its present site, but were allotted a place to build at Coyote Water, a small spring on the east side of the mesa, just under the gap. They had not lived there very long, however, when for some valuable services in defeating at one time a raid of the Ute (who used to be called the Tcingawúptuh) and of the Navajo at another, they were given for planting grounds all the space on the mesa summit from the gap to where Sichumovi now stands, and the same width, extending across the valley to the east. On the mesa summit they built the early portion of the house mass on the north side of the village, now known as Hano. But soon after this came a succession of dry seasons, which caused a great scarcity of food almost amounting to a famine, and many moved away to distant streams. The Asa people went to Túpkabi (Deep Canyon, the de Chelly), about 70 miles northeast from Walpi, where the Navajo received them kindly and supplied them with food. The Asa had preserved some seeds of the peach, which they planted in the canyon nooks, and numerous little orchards still flourish there. They also brought the Navajo new varieties of food plants, and their relations grew very cordial. They built houses along the base of the canyon walls, and dwelt there for two or three generations, during which time many of the Asa women were given to the Navajo, and the descendants of these now constitute a numerous clan among the Navajo, known as the Kiáini, the High-house people.

The Navajo and the Asa eventually quarreled and the latter returned to Walpi, but this was after the arrival of the Hano, by whom they 31 found their old houses occupied. The Asa were taken into the village of Walpi, being given a vacant strip on the east edge of the mesa, just where the main trail comes up to the village. The Navajo, Ute, and Apache had frequently gained entrance to the village by this trail, and to guard it the Asa built a house group along the edge of the cliff at that point, immediately overlooking the trail, where some of the people still live; and the kiva there, now used by the Snake order, belongs to them. There was a crevice in the rock, with a smooth bottom extending to the edge of the cliff and deep enough for a ki´koli. A wall was built to close the outer edge and it was at first intended to build a dwelling house there, but it was afterward excavated to its present size and made into a kiva, still called the wikwálhobi, the kiva of the Watchers of the High Place. The Walpi site becoming crowded, some of the Bear and Lizard people moved out and built houses on the site of the present Sichumovi; several Asa families followed them, and after them came some of the Badger people. The village grew to an extent considerably beyond its present size, when it was abandoned on account of a malignant plague. After the plague, and within the present generation, the village was rebuilt—the old houses being torn down to make the new ones.

After the Asa came the nest group to arrive was the Water family. Their chief begins the story of their migration in this way:

In the long ago the Snake, Horn, and Eagle people lived here (in Tusayan), but their corn grew only a span high, and when they sang for rain the cloud god sent only a thin mist. My people then lived in the distant Pa-lát Kwá-bi in the South. There was a very bad old man there, who, when he met any one, would spit in his face, blow his nose upon him, and rub ordure upon him. He ravished the girls and did all manner of evil. Baholikonga got angry at this and turned the world upside down, and water spouted up through the kivas and through the fireplaces in the houses. The earth was rent in great chasms, and water covered everything except one narrow ridge of mud; and across this the serpent deity told all the people to travel. As they journeyed across, the feet of the bad slipped and they fell into the dark water, but the good, after many days, reached dry land. While the water was rising around the village the old people got on the tops of the houses, for they thought they could not struggle across with the younger people; but Baholikonga clothed them with the skins of turkeys, and they spread their wings out and floated in the air just above the surface of the water, and in this way they got across. There were saved of our people Water, Corn, Lizard, Horned Toad, Sand, two families of Rabbit, and Tobacco. The turkey tail dragged in the water—hence the white on the turkey tail now. Wearing these turkey-skins is the reason why old people have dewlaps under the chin like a turkey; it is also the reason why old people use turkey-feathers at the religious ceremonies.

In the story of the wandering of the Water people, many vague references are made to various villages in the South, which they constructed or dwelt in, and to rocks where they carved their totems at temporary halting places. They dwelt for a long time at Homólobi, where the Sun people joined them; and probably not long after the latter left the Water people followed on after them. The largest number of this family seem 32 to have made their dwellings first at Mashongnavi and Shupaulovi; but like the Sun people they soon spread to all the villages.

The narrative of part of this journey is thus given by the chief before quoted:

It occupied 4 years to cross the disrupted country. The kwakwanti (a warrior order) went ahead of the people and carried seed of corn, beans, melons, squashes, and cotton. They would plant corn in the mud at early morning and by noon it was ripe and thus the people were fed. When they reached solid ground they rested, and then they built houses. The kwakwanti were always out exploring—sometimes they were gone as long as four years. Again we would follow them on long journeys, and halt and build houses and plant. While we were traveling if a woman became heavy with child we would build her a house and put plenty of food in it and leave her there, and from these women sprang the Pima, Maricopa, and other Indians in the South.

Away in the South, before we crossed the mountains (south of the Apache country) we built large houses and lived there a long while. Near these houses is a large rock on which was painted the rain-clouds of the Water phratry, also a man carrying corn in his arms; and the other phratries also painted the Lizard and the Rabbit upon it. While they were living there the kwakwanti made an expedition far to the north and came in conflict with a hostile people. They fought day after day, for days and days—they fought by day only and when night came they separated, each party retiring to its own ground to rest. One night the cranes came and each crane took a kwakwanti on his back and brought them back to their people in the South.

Again all the people traveled north until they came to the Little Colorado, near San Francisco Mountains, and there they built houses up and down the river. They also made long ditches to carry the water from the river to their gardens. After living there a long while they began to be plagued with swarms of a kind of gnat called the sand-fly, which bit the children, causing them to swell up and die. The place becoming unendurable, they were forced again to resume their travels. Before starting, one of the Rain-women, who was big with child, was made comfortable in one of the houses on the mountain. She told her people to leave her, because she knew this was the place where she was to remain forever. She also told them, that hereafter whenever they should return to the mountain to hunt she would provide them with plenty of game. Under her house is a spring and any sterile woman who drinks of its water will bear children. The people then began a long journey to reach the summit of the table land on the north. They camped for rest on one of the terraces, where there was no water, and they were very tired and thirsty. Here the women celebrated the rain-feast—they danced for three days, and on the fourth day the clouds brought heavy rain and refreshed the people. This event is still commemorated by a circle of stones at that place. They reached a spring southeast from Káibitho (Kumás Spring) and there they built a house and lived for some time. Our people had plenty of rain and cultivated much corn and some of the Walpi people came to visit us. They told ns that their rain only came here and there in fine misty sprays, and a basketful of corn was regarded as a large crop. So they asked us to come to their land and live with them and finally we consented. When we got there we found some Eagle people living near the Second Mesa; our people divided, and part went with the Eagle and have ever since remained there; but we camped near the First Mesa. It was planting time and the Walpi celebrated their rain-feast but they brought only a mere misty drizzle. Then we celebrated our rain-feast and planted. Great rains and thunder and lightning immediately followed and on the first day after planting our corn was half an arm’s length high; on the fourth day it was its full height, and in one moon it was ripe. When we were going up to the village (Walpi was then north of the gap, probably), we were met by a 33 Bear man who said that our thunder frightened the women and we must not go near the village. Then the kwakwanti said, “Let us leave these people and seek a land somewhere else,” but our women said they were tired of travel and insisted upon our remaining. Then “Fire-picker” came down from the village and told us to come up there and stay, but after we had got into the village the Walpi women screamed out against us—they feared our thunder—and so the Walpi turned us away. Then our people, except those who went to the Second Mesa, traveled to the northeast as far as the Tsegi (Canyon de Chelly), but I can not tell whether our people built the louses there. Then they came hack to this region again and built houses and had much trouble with the Walpi, but we have lived here ever since.

Groups of the Water people, as already stated, were distributed among all the villages, although the bulk of them remained at the Middle Mesa; but it seems that most of the remaining groups subsequently chose to build their permanent houses at Oraibi. There is no special tradition of this movement; it is only indicated by this circumstance, that in addition to the Water families common to every village, there are still in Oraibi several families of that people which have no representatives in any of the other villages. At a quite early day Oraibi became a place of importance, and they tell of being sufficiently populous to establish many outlying settlements. They still identify these with ruins on the detached mesas in the valley to the south and along the Moen-kopi (“place of flowing water”) and other intermittent streams in the west. These sites were occupied for the purpose of utilizing cultivable tracts of land in their vicinity, and the remotest settlement, about 45 miles west, was especially devoted to the cultivation of cotton, the place being still called by the Navajo and other neighboring tribes, the “cotton planting ground.” It is also said that several of the larger ruins along the course of the Moen-kopi were occupied by groups of the Snake, the Coyote, and the Eagle who dwelt in that region for a long period before they joined the people in Tusayan. The incursions of foreign bands from the north may have hastened that movement, and the Oraibi say they were compelled to withdraw all their outlying colonies. An episode is related of an attack upon the main village when a number of young girls were carried off, and 2 or 3 years afterward the same marauders returned and treated with the Oraibi, who paid a ransom in corn and received all their girls back again. After a quiet interval the pillaging bands renewed their attacks and the settlements on the Moen-kopi were vacated. They were again occupied after another peace was established, and this condition of alternate occupancy and abandonment seems to have existed until within quite recent time.