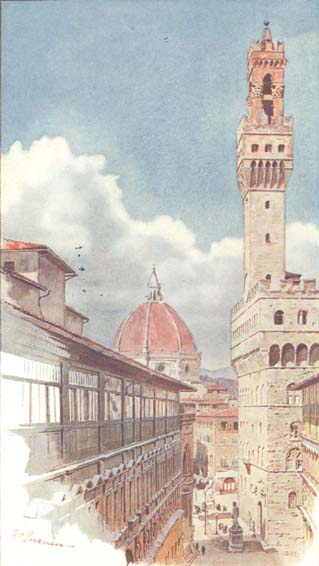

FROM THE UFFIZI

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Florence and Northern Tuscany with Genoa

by Edward Hutton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Florence and Northern Tuscany with Genoa

With Sixteen Illustrations In Colour By William Parkinson

And Sixteen Other Illustrations, Second Edition

Author: Edward Hutton

Release Date: August 8, 2005 [EBook #16477]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FLORENCE ***

Produced by Ted Garvin, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

TO MY FRIEND WILLIAM HEYWOOD

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The traveller who on his way to Italy passes along the Riviera di Ponente, through Marseilles, Nice, and Mentone to Ventimiglia, or crossing the Alps touches Italian soil, though scarcely Italy indeed, at Turin, on coming to Genoa finds himself really at last in the South, the true South, of which Genoa la Superba is the gate, her narrow streets, the various life of her port, her picturesque colour and dirt, her immense palaces of precious marbles, her oranges and pomegranates and lemons, her armsful of children, and above all the sun, which lends an eternal gladness to all these characteristic or delightful things, telling him at once that the North is far behind, that even Cisalpine Gaul is crossed and done with, and that here at last by the waves of that old and great sea is the true Italy, that beloved and ancient land to which we owe almost everything that is precious and valuable in our lives, and in which still, if we be young, we may find all our dreams. What to us are the weary miles of Eastern France if we come by road, the dreadful tunnels full of despair and filth if we come by rail, now that we have at last returned to her, or best of all, perhaps, found her for the first time in 2the spring at twenty-one or so, like a fair woman forlorn upon the mountains, the Ariadne of our race who placed in our hand the golden thread that led us out of the cavern of the savage to the sunlight and to her. But though, indeed, I think all this may be clearer to those who come to her in their first youth by the long white roads with a song on their lips and a dream in their hearts—for the song is drowned by the iron wheels that doubtless have their own music, and the dream is apt to escape in the horror of the night imprisoned with your fellows; still, as we are so quick to assure ourselves, there are other ways of coming to Italy than on foot: in a motor-car, for instance, our own modern way, ah! so much better than the train, and truly almost as good as walking. For there is the start in the early morning, the sweet fresh air of the fields and the hills, the long halt at midday at the old inn, or best of all by the roadside, the afternoon full of serenity, that gradually passes into excitement and eager expectancy as you approach some unknown town; and every night you sleep in a new place, and every morning the joy of the wanderer is yours. You never "find yourself" in any city, having won to it through many adventures, nor ever are you too far away from the place you lay at on the night before. And so, as you pass on and on and on, till the road which at first had entranced you, wearies you, terrifies you, relentlessly opening before you in a monstrous white vista, and you who began by thinking little of distance find, as I have done, that only the roads are endless, even for you too the endless way must stop when it comes to the sea; and there you have won at last to Italy, at Genoa.

If you come by Ventimiglia, starting early, all the afternoon that white vision will rise before you like some heavenly city, very pure and full of light, beckoning you even from a long way off across innumerable and lovely bays, splendid upon the sea. While if you come from Turin, it is only at sunset you will see her, suddenly in a cleft of the mountains, the sun just gilding the Pharos before night comes over the 3sea, opening like some great flower full of coolness and fragrance.

It was by sea that John Evelyn came to Genoa after many adventures; and though we must be content to forego much of the surprise and romance of an advent such as that, yet for us too there remain many wonderful things which we may share with him. The waking at dawn, for instance, for the first time in the South, with the noise in our ears of the bells of the mules carrying merchandise to and from the ships in the Porto; the sudden delight that we had not felt or realised, weary as we were on the night before, at finding ourselves really at last in the way of such things, the shouting of the muleteers, the songs of the sailors getting their ships in gear for the seas, the blaze of sunlight, the pleasant heat, the sense of everlasting summer. These things, and so much more than these, abide for ever; the splendour of that ancient sea, the gesture of the everlasting mountains, the calmness, joy, and serenity of the soft sky.

Something like this is what I always feel on coming to that proud city of palaces, a sort of assurance, a spirit of delight. And in spite of all Tennyson may have thought to say, for me it is not the North but the South that is bright "and true and tender." For in the North the sky is seldom seen and is full of clouds, while here it stretches up to God. And then, the South has been true to all her ancient faiths and works, to the Catholic religion, for instance, and to agriculture, the old labour of the corn and the wine and the oil, while we are gone after Luther and what he leads to, and, forsaking the fields, have taken to minding machines.

And so, in some dim way I cannot explain, to come to Italy is like coming home, as though after a long journey one were to come suddenly upon one's mistress at a corner of the lane in a shady place.

It is perhaps with some such joy in the heart as this that the fortunate traveller will come to Genoa the Proud, by the sea, lying on the bosom of the mountains, whiter than the foam of her waves, the beautiful gate of Italy.

The history of Genoa, its proud and adventurous story, is almost wholly a tale of the sea, full of mystery, cruelty, and beauty, a legend of sea power, a romance of ships. It is a narrative in which sailors, half merchants, half pirates, adventurers every one, put out from the city and return laden with all sorts of spoil,—gold from Africa, slaves from Tunis or Morocco, the booty of the Crusades; with here the vessel of the Holy Grail bought at a great price, there the stolen dust of a great Saint.

This spirit of adventure, which established the power of Genoa in the East, which crushed Pisa and almost overcame Venice, was held in check and controlled by the spirit of gain, the dream of the merchant, so that Columbus, the very genius of adventure almost without an after-thought, though a Genoese, was not encouraged, was indeed laughed at; and Genoa, splendid in adventure but working only for gain, unable on this account to establish any permanent colony, losing gradually all her possessions, threw to the Spaniard the dominion of the New World, just because she was not worthy of it. Men have called her Genoa the Proud, and indeed who, looking on her from the sea or the sea-shore, will ever question her title?—but the truth is, that she was not proud enough. She trusted in riches; for her, glory was of no account if gold were not added to it. If she entered the first Crusade as a Christian, it was really her one disinterested action; and all the world acknowledged her valour and her contrivance which won Jerusalem. But in the second Crusade, as in the next, she no longer thought of glory or of the Tomb of Jesus, she was intent on money; and since in that stony place but little booty could be hoped for, she set herself to spoil the Christian, to provide him at a price with ships, with provender, with the means of realising his dream, a dream at which she could afford to laugh, secure as she was in the possession of this world's goods. Then, when in the thirteenth century those vast multitudes of soldiers, monks, 5dreamers, beggars, and adventurers came to her, the port for Palestine, clamouring for transports, she was sceptical and even scornful of them, but willing to give them what they demanded, not for the love of God but for a price. Even that beautiful and mysterious army of children which came to her from France and Germany in 1212 seeking Jesus, she could hold in contempt till, weary at last of feeding them, she found the galleys they demanded, and in the loneliness of the sea betrayed them and sold them for gold as slaves to the Arabs, so that of the seven thousand boys and girls led by a lad of thirteen who came at the bidding of a voice to Genoa, not one ever returned, nor do we hear anything further concerning them but the rumour of their fate.

Thus Genoa appears to us of old and now, too, as a city of merchants. She crushed Pisa lest Pisa should become richer than herself; she went out against the Moors for Castile because of a whisper of the booty; she sought to overthrow Venice because she competed with her trade in the East; and to-day if she could she would fill up the harbour of Savona with stones, as she did in the sixteenth century, because Savona takes part of her trade from her. What Philip of Spain did for God's sake, what Visconti did for power, what Cesare Borgia did for glory, Genoa has done for gold. She is a merchant adventurer. Her true work was the Bank of St. George. One of the most glorious and splendid cities of Italy, she is, almost alone in that home of humanism, without a school of art or a poet or even a philosopher. Her heroes are the great admirals, and adventurers—Spinola, Doria, Grimaldi, Fieschi, men whose names linger in many a ruined castle along the coast who of old met piracy with piracy. Even to-day a Grimaldi spoils Europe at Monaco, as his ancestors did of old.

One saint certainly of her own stock she may claim, St. Catherine Adorni, born in 1447. But the Renaissance passed her by, giving her, it is true, by the hands of an alien, the streets of splendid palaces we know, but neither churches nor pictures; such paintings as she possesses being the sixteenth 6century work of foreigners, Rubens, Vandyck, Ribera, Sanchez Coello, and maybe Velasquez.

Yet barren though she is in art, at least Genoa has ever been fulfilled with life. If her aim was riches she attained it, and produced much that was worth having by the way. Without the appeal of Florence or Siena or Venice or Rome, she is to-day, when they are passed away into dreams or have become little more than museums, what she has ever been, a city of business, the greatest port in the Mediterranean, a city full of various life,—here a touch of the East, there a whisper of the West, a busy, brutal, picturesque city, beauty growing up as it does in London, suddenly for a moment out of the life of the place, not made or contrived as in Paris or Florence, but naturally, a living thing, shy and evanescent. Here poverty and riches jostle one another side by side as they do in life, and are antagonistic and hate one another. Yet Genoa, alone of all the cities of Italy proper is living to-day, living the life of to-day, and with all her glorious past she is as much a city of the twentieth century as of any other period of history. For, while others have gone after dreams and attained them and passed away, she has clung to life, and the god of this world was ever hers. She has made to herself friends of the mammon of unrighteousness, and they have remained faithful to her. Her ports grow and multiply, her trade increases, still she heaps up riches, and if she cannot tell who shall gather them, at least she is true to herself and is not dependent on the stranger or the tourist. The artist, it is said, is something of a daughter of joy, and in thinking of Florence or Venice, which live on the pleasure of the stranger, we may find the truth of a saying so obvious. Well, Genoa was never an artist. She was a leader, a merchant, with fleets, with argosies, with far-flung companies of adventure. Through her gates passed the silks and porcelains of the East, the gold of Africa, the slaves and fair women, the booty and loot of life, the trade of the world. This is her secret. She is living among the dead, who may or may not awaken.

7If you are surprised in her streets by the greatness of old things, it is only to find yourself face to face with the new. People, tourists do not linger in her ways—they pass on to Pisa. Genoa has too little to show them, and too much. She is not a museum, she is a city, a city of life and death and the business of the world. You will never love her as you will love Pisa or Siena or Rome or Florence, or almost any other city of Italy. We do not love the living as we love the dead. They press upon us and contend with us, and are beautiful and again ugly and mediocre and heroic, all between two heart beats; but the dead ask only our love. Genoa has never asked it, and never will. She is one of us, her future is hidden from her, and into her mystery none has dared to look. She is like a symphony of modern music, full of immense gradual crescendos, gradual diminuendos, unknown to the old masters. Only Rome, and that but seldom, breathes with her life. But through the music of her life, so modern, so full of a sort of whining and despair in which no great resolution or heroic notes ever come, there winds an old-world melody, softly, softly, full of the sun, full of the sea, that is always the same, mysterious, ambiguous, full of promises, at her feet.

The gate of Italy, I said in speaking of her, and indeed it is one of the derivations of her name Genoa,—Janua the gate, founded, as the fourteenth-century inscription in the Duomo asserts, by Janus, a Trojan prince skilled in astrology, who, while seeking a healthy and safe place for his dwelling, sailed by chance into this bay, where was a little city founded by Janus, King of Italy, a great-grandson of Noah, and finding the place such as he wished, he gave it his name and his power. Now, whether the great-grandson of Noah was truly the original founder of the city, or Janus the Trojan, or another, it is certainly older than the Christian religion, so that some have thought that Janus, that old god who once presided at 8the beginning of all noble things, was the divine originator of this city also. And remembering the sun that continually makes Genoa to seem all of precious stone, of moonstone or alabaster, it seems indeed likely enough, for Janus was worshipped of old as the sun, he opened the year too, and the first month bears his name; and while on earth he was the guardian deity of gates, in heaven he was porter, and his sign was a ship; therefore he may well have taken to himself the city of ships, the gateway of Italy, Genoa.

And through that gate what beautiful, terrible, and mysterious things have passed into oblivion; Saints who have perhaps seen the very face of Jesus; legions strong in the everlasting name of Caesar, that have lost themselves in the fastnesses of the North; sailors mad with the song of the sirens. On her quays burned the futile enthusiasm of the Middle Age, that coveted the Holy City and was overwhelmed in the desert. Through her streets surged Crusade after Crusade, companies of adventure, lonely hermits drunken with silence, immense armies of dreamers, the chivalry of Europe, a host of little children. On her ramparts Columbus dreamed, and in her seas he fought with the Tunisian galleys before he set sail westward for El Dorado. And here Andrea Doria beat the Turks and blockaded his own city and set her free; and S. Catherine Adorni, weary of the ways of the world, watched the galleons come out of the west, and prayed to God, and saw the wind over the sea. O beautiful and mysterious armies, O little children from afar, and thou whose adventurous name married our world, what cities have you taken, what new love have you found, what seas have your ships furrowed; whither have you fled away when Genoa was so fair?

It was about the year 50 when St. Nazarus and St. Celsus, fleeing from the terror of Nero, landed not far away to the east at Albaro, bringing with them the new religion. A lane leading down to the sea still bears the name of one of them, and, strangely as we may think, a ruined church marks the 9spot crowning the rock above the place, where a Temple of Venus once stood. Yet perhaps the earliest remnant of old Genoa is to be found in the Church of S. Sisto in the Via di Prè, standing as it does on the very stones of a church raised to the Pope and martyr of that name in 260. In the journey which Pope Sixtus made to Genoa he is said to have been accompanied by St. Laurence, and it is probable that a church was built not much later to him also on the site of the Duomo. However this may be, Genoa appears to have been passionately Christian, for the first authority we hear of is that of the Bishops, to whom she seems to have submitted herself enthusiastically, installing them in the old castello in that the most ancient part of the city around Piazza Sarzano and S. Maria di Castello. This castello, destroyed in the quarrels of Guelph and Ghibelline, as some have thought, may be found in the hall-mark of the silver vessels made here under the Republic. Very few are the remnants that have come down to us from the time of the Bishops. An inscription, however, on a house in Via S. Luca close to S. Siro remains, telling how in the year 580 S. Siro destroyed the serpent Basilisk. In the church itself a seventeenth-century fresco commemorates this monstrous deed.

Of the Lombard dominion something more is left to us; the story at least of the passing of the dust of St. Augustine. It seems that at the beginning of the sixth century these sacred ashes had been brought from Africa to Cagliari to save them from the Vandals. For more than two hundred years they remained at Cagliari, when, the Saracens taking the place, Luitprand, the Lombard king, remembering S. Ambrogio and Milan, ransomed them for a great price and had them brought in 725 to Genoa, where they were shown to the people for many days. Luitprand himself came to Genoa to meet them and placed them in a silver urn, discovered at Pavia in 1695, and carried them in state across the Apennines. Some of the beautiful Lombard towers, such as S. Stefano and S. Agostino, where the ashes are said to have been exposed, remind us perhaps more nearly of the Lombard 10dominion. Then came Charlemagne and his knights and the great quarrel. But though Genoa now belonged to the Holy Roman Empire, she was not strong enough to defend herself from the raids of the Saracens, who in the earlier part of the tenth century burnt the city and led half the population into captivity.

Perhaps it is to Otho that Genoa owes her first impulse towards greatness: he gave her a sort of freedom at any rate. And immediately after his day the Genoese began to make way against the Saracens on the seas. You may see a relic of some passing victory in the carved Turk's head on a house at the corner of Via di Prè and Vico dei Macellai. Nor was this all, for about this time Genoa seized Corsica, that fatal island which not only never gave her peace, but bred the immortal soldier who was finally to crush her and to end her life as a free power.

There follow the Crusades. These splendid follies have much to do with the wealth and greatness of Genoa. It was from her port that Godfrey de Bouillon set sail in the Pomella as a pilgrim in 1095. He appears to have been insulted at the very gate of Jerusalem, or, as some say, at the door of the Holy Sepulchre. At any rate he returned to Europe, where Urban II, urged by Peter the Hermit, was already half inclined to proclaim the First Crusade. Godfrey's story seems to have decided him; and, indeed, so moving was his tale, that the crowd who heard him cried out urging the Pope to act, Dieu le veult, the famous and fatal cry that was to lead uncounted thousands to death, and almost to widow Europe. In Genoa the war was preached furiously and with success by the Bishops of Gratz and Arles in S. Siro. An army of enthusiasts, monks, beggars, soldiers, adventurers, and thieves, moved partly by the love of Christ, partly by love of gain, gathered in Genoa. With them was Godfrey. They sailed in 1097: they besieged Antioch and took it. Content it might seem with this success, or fearful in that stony place of venturing too far from the sea, the Genoese returned, not empty. For on the way back, storm- 11bound perhaps in Myra, they sacked a Greek monastery there, carrying off for their city the dust of St. John Baptist, which to-day is still in their keeping.

Was it the hope of loot that caused Genoa in 1099 to send even a larger company to Judaea under the great Guglielmo Embriaco, whose tower to-day is all that is left of what must once have been a city of towers? Who knows? He landed with his Genoese at Joppa, burnt his ships as Caesar did, though doubtless he thought not of it, and marching on Jerusalem found the Christians still unsuccessful and the Tomb of Christ, as now, ringed by pagan spears. But the Genoese were not to be denied. If the valour of Europe was of no avail, the contrivance of the sea, the cunning of Genoa must bring down Saladin. So they set to work and made a tower of scaffolding with ropes, with timbers, with spars saved from their ships. When this was ready, slowly, not without difficulty, surely not without joy, they hauled and heaved and drove it over the burning dust, the immense wilderness of stones and refuse that surrounded Jerusalem. Then they swarmed up with songs, with shouting, and leapt on to the walls, and over the ramparts into the Holy City, covered with blood, filled with the fury of battle, wounded, dying, mad with hatred, to the Tomb of Jesus, the empty sepulchre of God.

Then eight days after came that strange election, when we offered the throne of Palestine to Godfrey of Bouillon; but he refused to wear a crown of gold where his Saviour had worn one of thorns, so we proclaimed him Defender of the Holy Sepulchre.

But the Genoese under Embriaco as before returned home, again not without spoil. And their captain for his portion claimed the Catino, the famous vessel, fashioned as was thought of a single emerald, truly, as was believed, the vessel of the Holy Grail, the cup of the Last Supper, the basin of the Precious Blood. To-day, if you are fortunate, as you look at it in the Treasury of S. Lorenzo, they tell you it is only green glass, and was broken by the French who carried 12it to Paris. But, indeed, what crime would be too great in order to possess oneself of such a thing? It was an emerald once, and into it the Prince of Life had dipped His fingers; Nicodemus had held it in his trembling hands to catch the very life of God; who knows what saint or angry angel in the heathen days of Napoleon, foreseeing the future, snatched it away into heaven, giving us in exchange what we deserved. Surely it was an emerald once? Is it possible that a Genoese gave up all his spoil for a green glass, a cracked pipkin, a heathen wash pot, empty, valueless, a fraud?—I'll not believe it.

Embriaco, however, returned once more to Palestine with his men, fighting under Godfrey at Cesarea; and again he came home in triumph, his galleys low with spoil. And indeed, though we hear no more of Embriaco, by the end of the first Crusade, Genoa had won possessions in the East,—streets in Jaffa, streets in Jerusalem, whole quarters in Antioch, Cesarea, Tyre, and Acre, not to speak of an inscription in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, "Prepotens Genuensium Presidium," which Godfrey had carved there, while the Pope gave them their cross of St. George as arms, which, as some say, we got from them.

Strangely as we may think, in the second Crusade, and even in the third, so disastrous for the Christian arms, Genoa bore no part; no part, that is, in the fighting, though in the matter of commissariat and shipping she was not slow to come forward and make a fortune. And indeed, she had enough to do at home; for Pisa, no less slow to join the Crusades, became her enemy, jealous of her growing power and of her possession of Corsica, so that in 1120 war broke out between them, which scarcely ceased till Pisa was finally beaten on the sea, and the chains of Porto Pisano were hanging on the Palazzo di S. Giorgio.

Soon, however, Genoa was engaged in a more profitable business, an affair after her own heart, in which valour was not its own reward,—I mean, in the expedition in 1147 against the Moors in Spain. Certainly the Pope, Eugenius III it was, 13urged them to it, but so they had been urged to fight against Saladin without arousing enthusiasm. Yet in this new cause all Genoa was at fever heat. Wherefore? Well, Granada was a great and wealthy city, whereas Jerusalem was a ruined village. So they sent thirty thousand men with sixty galleys and one hundred and sixty transports to Almeria, which after some hard fighting, for your Moor was never a coward, they took, with a huge booty. In the next year they took Tortosa, and returned home laden with spoil, silver lamps for the shrine of St. John Baptist, for instance, and women and slaves.

Still, Genoa had no peace, for we find her making a stout and successful defence shortly after against Frederic I, the whole city, men, women, and children, on his approach from Lombardy, building a great wall about the city in fifty-three days, of which feat Porta S. Andrea remains the monument. Then followed that pestilence of Guelph and Ghibelline; out of which rose the names of the great families, robbers, oppressors, tyrants,—Avvocato, Spinola, Doria, the Ghibellines, with the Guelphs, Castelli, Fieschi, Grimaldi. Nor was Genoa free of them till the great Admiral Andrea Doria crushed them for ever. Yet peace of a sort there was, now and again, in 1189 for instance, when Saladin won back Jerusalem, and the Guelph nobles volunteered in a body to serve against him, leaving Genoa to the Ghibellines, who established the foreign Podestà for the first time to rule the city. But this gave them no peace, for still the nobles fought together, and if one family became too powerful, confusion became worse confounded, for Guelph and Ghibelline joined together to bring it low. Thus in the thirteenth century you find Ghibelline Doria linked with the Guelph Grimaldi and Fieschi to break Ghibelline Spinola. The aspect of the city at that time was certainly very different from the city of to-day, which is mainly of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries where it is not quite modern. Then each family had its tower, from which it fought or out of which it issued, making the streets a shambles as it followed the enemy home or sought him out. The ordinary citizen must have had an 14anxious time of it with these bands of idle cut-throats at large. But by the close of the twelfth century the towers, at any rate, had been destroyed by order of the Consuls, the only one left being that which we see to-day, Torre degli Embriachi, left as a monument to a cunning valour. The thirteenth century saw the domination of the Spinola family, or rather of one branch of it, the Luccoli Spinola, which as opposed to the old S. Luca branch seems to have lived nearer the country and the woods, and was apparently most disastrous for the internal peace of the city; and indeed, until the Luccoli were beaten and exiled, as happened in the beginning of the fourteenth century, there could be no peace; truly the only peace Genoa knew in those days was that of a foreign war, when the great lords went out against Pisa or Venice.

The Venetian war, unlike that against Pisa, ended disastrously. Its origin was a question of trade in the East, where the Comneni had given certain rights to Genoa which on their fall the Venetians refused to respect. The quarrel came to a head in that cause of so many quarrels, the island of Crete, for the Marquis of Monferrat had sold it to the Venetians while he offered it to the Genoese, he himself having received it as spoil in the fourth Crusade. In this quarrel with Venice, Genoa certainly at first had the best of it. In 1261, or thereabout, she founded two colonies at Pera and Caffa, on the Bosphorus and in the Euxine, thus adding to her empire, which was rather a matter of business than of dominion. This is illustrated very effectually by the history of the Bank of St. George, which from this time till its dissolution at the end of the eighteenth century was, as it were, the heart of Genoa. It was Guglielmo Boccanegra, the grandfather of a more famous son, who built the palace which, as we now see it on the quay, is so sad and ruinous a monument to the independent greatness of the city. And since its stones were, as it is said, brought from Constantinople, where Michael Paleologus had given the Genoese the Venetian fortress of Pancratone, it is really a monument of the hatred of Genoa for Venice that we see there, the principal door 15being adorned with three lions' heads, part of the spoil of that Venetian fortress. This palace, on the death of Boccanegra, Captain of the People, was used by the city as an office for the registration of the compere or public loans, which dated from 1147 and the Moorish expedition. From the time of the foundation of the Bank the shares were, like our consols, to be bought and sold and were guaranteed by the city herself, though it was not till 1407 that the loans were consolidated and the Palazzo delle Compere, as it was called, became the Banco di S. Giorgio. Indeed, though its real power may be doubted, it administered, in name at any rate, the colonies of Genoa after the fall of Constantinople.

Of the building itself I speak elsewhere; it is rather to its place in the story of Genoa that I have wished here to draw attention.

And it was now, indeed, that Genoa reached, perhaps, the zenith of her power. For in 1284 comes the great victory of Meloria, which laid Pisa low. Enraged partly at the success of Genoa in the East, partly at her growing power and general wealth, Pisa, with that extraordinary flaming and ruthless energy so characteristic of her, determined to dispose of Genoa once and for all. Nor were the Genoese unwilling to meet her. Indeed, they urged her to it. The two fleets, bearing some sixty thousand men, that of Pisa commanded by a Venetian, Andrea Morosini, that of Genoa by Oberto Doria, met at Meloria, not far from Bocca d'Arno, when the Pisans were utterly defeated, partly owing to the treachery of the immortal Count Ugolino, who sailed away without striking a blow. [1] Yet in spite of her defeat Pisa carried on the war for four years, when she sued for peace, which, however, she could not keep, so that in 1290 we find Corrado Doria sailing into the Porto Pisano, breaking the chain which guarded it, and carrying it back to Genoa, where part of it hung as a trophy till our own time on the façade of the Palazzo di S. Giorgio.

Nor were the Genoese content, for soon after this victory 16we find them, led by Lamba Doria, utterly beating the Venetians at Curzola, in the Adriatic, where they took a famous prisoner, Messer Marco Polo, just returned from Asia. They brought him back to Genoa, where he remained in prison for nearly two years, and wrote his masterpiece. Whether it was the influence of so illustrious a captive, or merely the natural expression of their own splendid and adventurous spirit, about this time the Doria fitted out two galleys to explore the western seas, and to try to reach India by way of the sunset. Tedisio Doria and the brothers Vivaldi with some Franciscans set out on this adventure, and never returned.

With the fourteenth century Genoa for a time threw off the yoke of her great nobles, Spinola, Doria, Grimaldi, Fieschi. The wave of revolt that passed over Europe at this time certainly left Genoa freer than she had ever been. The people had claimed to name their own "Abbate," in opposition to the Captain of the People. They chose by acclamation Simone Boccanegra, who, however, seeing that he was to have no power, refused the office. "If he will not be Abbate," cried a voice in the crowd, "let him be Doge"; and seeing the enthusiasm of the people, this great man allowed himself to be borne to S. Siro, where he was crowned first Doge of Genoa for life. The nobles seem to have been afraid to interfere, so great was the eagerness of the people. And it was about this time that the Grimaldi, driven out of Genoa, seized Monaco, which by the sufferance of Europe they hold to-day. It is true, that for a time in 1344 the nobles gathered an army and returned to Genoa, Boccanegra resigning and exiling himself in Pisa; but twelve years later he was back again, ruling with temperance and wisdom that great city, which was now queen of the Mediterranean sea.

To follow the fortunes of the Republic one would need to write a book. It must be sufficient to say here that by the middle of the century war broke out with Venice, and was at first disastrous for Genoa. Then once more a Doria, Pagano it was, led her to victory at Sapienza, off the coast of Greece, 17where thirty-one Genoese galleys fought thirty-six of Venice and took them captive. But the nobles were never quiet, always they plotted the death of the Doge Giovanni da Morta, or Boccanegra. It was with the latter they were successful in 1363, when they poisoned him at a banquet in honour of the King of Cyprus—for they had possessed themselves of a city in that island. Thus the nobles came back into Genoa, Adorni, Fregosi, Guarchi, Montaldi, this time; lesser men, but not less disastrous for the liberty of Genoa than the older families. So they fought among themselves for mastery, till the Adorni, fearing to be beaten, sold the city to Charles VI of France, who made them his representative and gave them the government. And all this time the war with Venice continued. At first it promised success,—at Pola, for instance, where Luciano Doria was victorious, but at last beaten at Chioggia, and not knowing where to turn to make terms, the supremacy of the seas passed from Genoa to Venice, peace coming at last in 1381.

Then the Genoese turned their attention to the affairs of their city. In the first year of the fifteenth century they rose to throw off the French yoke. But France was not so easily disposed of. She sent Marshal Boucicault to rule in Genoa; and he built the Castelletto, which was destroyed only a few years ago in our father's time. In 1409, however, Boucicault thought to gain Milan, for Gian Galeazzo Visconti was dead. In his absence the Genoese rose and threw out the French, preferring their own tyrants. These, Adorni, Montaldi, Fregosi, fought together till Tommaso Fregosi, fearing that the others might prove too strong for him, sold the city to Filippo Maria Visconti, tyrant of Milan. So the Visconti came to rule in Genoa.

This period, full of the confusion of the petty wars of Italy, while Sforza was plotting for his dukedom and Malatesta was building his Rocca in Rimini; while the Pope was a fugitive, and the kingdom of Naples in a state of anarchy, is famous, so far as Genoa is concerned, for her victory at sea over King Alfonso of Aragon, pretender against 18René of Anjou to the throne of Naples. The Visconti sided with the House of Anjou, and Genoa, in their power for the moment, fought with them; so that Biagio Assereto, in command of the Genoese fleet, not only defeated the Aragonese, but took Alfonso prisoner, together with the King of Navarre and many nobles. That victory, strangely enough, made an end of the rule of the Visconti in Genoa. For, seeing his policy led that way, Filippo Maria Visconti ordered the Genoese to send their illustrious prisoners to Milan, where he made much of them, fearing now rather the French than the Spaniards, since the Genoese had disposed of the latter and so made the French all-powerful. This spoliation, however, enraged the Genoese, who joined the league of Florence and Venice, deserting Milan. At the word of Francesco Spinola they rose, in 1436, killed the Milanese governor outside the Church of S. Siro, and once more declared a Republic. To little purpose, as it proved, for the feuds betwixt the great families continued, so that by 1458 we find Pietro Fregosi, fearing the growing power of the Adorni, and hard pressed by King Alfonso, who never forgave an injury, handing over Genoa to Charles VIII of France.

Meantime, in 1453, Constantinople had fallen before Mahomet, and the colony of Galata was thus lost to Genoa. And though in this sorry business the Genoese seem to be less blameworthy than the rest of Christendom—for they with but four galleys defeated the whole Turkish fleet—Genoa suffered in the loss of Galata more than the rest, a fact certainly not lost upon Venice and Naples, who refused to move against the Turk, though the honour of Europe was pledged in that cause. But all Italy was in a state of confusion. Sforza, that fox who had possessed himself of the March of Ancona, and had never fought in any cause but his own, on the death of Visconti had with almost incredible guile seized Milan. He it was who helped the Genoese to throw out the French, only to take Genoa for himself. A man of splendid force and confidence, he ruled wisely, and alone of her rulers up to this time seems to have been 19regretted when, in 1466, he died, and was succeeded in the Duchy of Milan by his son Galeazzo. This man was a tyrant, and ruled like a barbarian, till his assassination in 1476. There followed a brief space of liberty in Genoa, liberty endangered every moment by the quarrels of the nobles, who at last proposed to divide the city among them, and would have thus destroyed their fatherland, had not Il Moro, Ludovico Sforza of Milan, intervened and possessed himself of Genoa, which he held till 1499, when Louis XII of France defeated him, Genoa placing herself under his protection.

Meanwhile Columbus, that mystical dreamer who might have restored to Genoa all and more than all she had lost in colonial dominion, was born and grew up in those narrow streets, and played on the lofty ramparts and learned the ways of ships. Genoa in her proud confusion heard him not, so he passed to Salamanca and the Dominicans, and set sail from Cadiz. Yet he never forgot Genoa, and indeed it is characteristic of those great men who are without honour in their own country, that they are ever mindful of her who has rejected them. The beautiful letter written to the Bank of St. George in 1498 from Seville, as he was about to set out on what proved to be his last voyage, is witness to this.

"Although my body," he writes, "is here, my heart is always with you. God has been more bountiful to me than to any one since David's time. The success of my enterprise is already clear, and would be still more clear if the Government did not cover it with a veil. I sail again for the Indies in the name of the Most Holy Trinity, and I return at once; but as I know I am but mortal, I charge my son Don Diego to pay you yearly and for ever the tenth part of all my revenue, in order to lighten the toll on wine and corn. If this tenth part is large you are welcome to it; if small, believe in my good wish. May the Most Holy Trinity guard your noble persons and increase the lustre of your distinguished office."

Such were the last words of Columbus to his native city. You may see his birthplace, the very house in which he was 20born, on your left in the Borgo dei Lanajoli, as you go down from the Porta S. Andrea.

It was in 1499 that Louis of France got possession of Genoa. He held the city, cowed as it was, till 1507, when, goaded into rebellion by insufferable wrongs, the people rose and threw out his Frenchmen with their own nobles, choosing as their Doge Paolo da Novi, a dyer of silk, one of themselves. Not for long, however, was Paolo to rule in Genoa, for Louis retook the city, and Paolo, who had fled to Pisa, was captured as he sailed for Rome, and put to death.

It was now that it came into the mind of Louis, who had learned nothing from experience, to build another fort like to the Castelletto, to wit the Briglia, to bridle the city. This he did, yet there lay the bridle on which he was to be ridden back to France. For the Genoese never forgave him his threat, which stood before them day by day, so that at the first opportunity, Julius II, Pope and warrior, helping them, they rose again, and again the French departed. And in 1515 Louis died, and Francis I ruled in his stead. Then, the nobles of Genoa quarrelling as ever among themselves, Fregoso agreed with the French king, who made him governor of the city. The Adorni, angry at this, made overtures to the Emperor, Charles V it was, who sent General Pescara and twenty thousand men to take the city. There followed that most bloody sack, to the cry of Spain and Adorni, which lives in history and in the hearts of the Genoese to this day. This happened in 1522, and thereafter Antoniotto Adorni became Doge as a reward for his treachery.

But already the deliverer was at hand, scarcely to be distinguished at first from an enemy. Five years were the length of Adorni's rule, and all that time the French attacked and strove for the city, and in their ranks fought he who was the deliverer, Andrea Doria, Lord Admiral of Genoa, the saviour of his country.

Then in 1527 the French got possession of Genoa. Now Filippino Doria, nephew to the Admiral, had won a victory in 21the Gulf of Palermo over the Spanish fleet. But Francis, that brilliant fool, thought nothing of this service, though he claimed the prisoners for himself, for he liked the ransom well. Then the Admiral, touched in his pride, threw over the French cause and joined the Emperor. In 1528 a common action between the fleet under Doria and the populace within the city once more threw out the French, and Doria entered Genoa amid the acclamation of the multitude, knight of the Golden Fleece and Prince of Melfi.

This extraordinary and heroic sailor, born at Oneglia in 1466 or 1468 of one of the princely houses of Genoa, before 1503 had served under many Italian lords. It was in 1513 that he first had the command of the fleet of Genoa, while three years later he defeated the Turks at Pianosa. He helped Francis into Genoa and he threw him out; while he lived he ruled the city he had twice subdued, and his glory was hers. Yet truly it might seem that all Doria did was but to transfer Genoa from the Spaniard to the Frenchman and back again. In reality, he won her for himself. He drove the French not only out of Genoa, but out of her dominion. He filled up the port of Savona with stones, because she had under French influence sought to rival Genoa. With him Genoa ruled the sea, and with his death her greatness departed. And he was as liberal as he was powerful. Charles V knew him, and let him alone. He himself as Lord of Genoa gave her back her liberties, set up the Senate again, opened the Golden Book, Il Libro d'Oro, and wrote in it the names of those who should rule; then he set up a parliament, the Grand Council of Four Hundred, and the old quarrels were forgotten, and there was peace.

But who could rule the Genoese, greedy as their sea, treacherous as their winds, proud as their sun, deep as their sky, cruel as their rocks! If the Admiral had brought the Adorni and the Fregosi low, there yet remained the Fieschi, old as the Doria, Guelph too, while they had been Ghibelline.

It is true that the old quarrels were done with, yet strangely enough it was on the Pope's behalf that the Fieschi 22plotted against the Doria. Now, Pope Paul III had been Doria's friend. In 1535 he had for a remembrance of his love given the Admiral that great sword which still hangs in S. Matteo. But now, when Andrea's brother, Abbate di San Fruttuoso came to die, and it was known that he had left the Admiral much property close to Naples, the Pope, swearing that the estates of an ecclesiastic necessarily returned to the Church, claimed Andrea's inheritance. But the Admiral thought differently. Ordering Giannettino, his nephew, to take the fleet to Civitavecchia, he seized the Pope's galleys and had them brought to Genoa. Now, when the Genoese saw this strange capture convoyed into Genoa—so the tale goes—they were afraid, and crowded round the old Admiral, demanding wherefore he made war on the Church, and some shouted sacrilege and others profanation, while others again besought him with tears what it meant. And he answered, so that all might hear, that it meant that his galleys were stronger than those of His Holiness.

Then the Pope, knowing his man, gave way, but forgot it not. So that he called Gian Luigi Fieschi to him, the head of that family, a Guelph of a Guelph stock, and put it into his mind to rise against the Admiral, and to hold Genoa himself under the protection of Francis I. The blow fell on 1st January 1547. Now, on the day before, the Admiral was unwell and lay a bed, so that Fieschi waited on him in the most friendly way, and, as it is said, kissed many times the two lads, grand-nephews of the Admiral, who played about the room. Not many hours later, the Fieschi were in the streets rousing the city. Giannettino, nephew to the Admiral, hearing the tumult, ran to the Porta S. Tommaso to hold it and enter the city, but that gate was already lost, and he himself soon dead. Truly, all seemed lost when Fieschi, going to seize the galleys, slipped from a plank into the water, and his armour drowned him. Then the House of Doria rallied, and their cry rang through the city; little by little they thrust back their enemies, they hemmed them in, 23they trod them under foot; before dawn all that were left of the Fieschi were flying to Montobbio, their castle in the mountains. Thus the Admiral gave peace to Genoa, nor was he content with the exile or death of his foes, for he destroyed also all their palaces, villas, and castles, spoiling thus half the city, and making way for the palaces which have named Genoa the City of Palaces, and which we know to-day. For thirteen years longer Andrea Doria reigned in Genoa, dying at last in 1560. And at his death all that might make Genoa so proud departed with him. In 1565 she lost Chios, the last of her possessions in the East, and before long she lay once more in the hands of foreigners, not to regain her liberty till in 1860 Italy rose up out of chaos and her sea bore the Thousand of Garibaldi to Sicily, to Marsala, to free the Kingdom.

As you stand under those strange arcades that run under the houses facing the port, all that most ancient story of Genoa seems actual, possible; it is as though in some extraordinarily vivid dream you had gone back to less uniform days, when the beauty and the ugliness of the world struggled for mastery, before the overwhelming victory of the machine had enthroned ugliness and threatened the dominion of the soul of man. In that shadowy place, where little shops like caverns open on either side, with here a woman grinding coffee, there a shoe-maker at his last, yonder a smith making copper pipkins, a sailor buying ropes, an old woman cheapening apples, everything seems to have stood still from century to century. There you will surely see the mantilla worn as in Spain, while the smell of ships, whose masts every now and then you may see, a whole forest of them, in the harbour, the bells of the mules, the splendour of the most ancient sun, remind you only of old things, the long ways of the great sea, the roads and the deserts and the mountains, the joy that cometh with the morning, so that there at any rate Genoa is 24as she ever was, a city of noisy shadowy ways, cool in the heat, full of life, movement, merchandise, and women.

And as it happens, this shadowy arcade, so close to the hotels (under which, indeed, you must make your way to reach one of the oldest of these hostelries, the Hôtel de la Ville), is a place to which the traveller returns again and again, weary of the garish modernity that has spoiled so much of the city, far at least from the tram lines that have made of so many Italian cities a pandemonium. It is from this characteristic pathway between the little shops that one should set out to explore Genoa.

Passing along this passage eastward, you soon come to the Bank of St. George, that black Dogana, built with Venetian stones from Constantinople, a monument of hatred and perhaps of love,—hatred of the Venetians, of the Pisans too, for here till our own time hung the iron chains of Porto Pisano that Corrado Doria took in 1290; and of love, since it was to preserve Genoa and her dominion that the Banca was founded. Over the door you may still see remnants of the device the Guelph Fieschi Pope, Innocent VII, gave to his native city when he came to see her, the griffin of Genoa strangling the imperial eagle and the fox of Pisa; while under is the motto, Griphus ut has agit, sic hostes Genua frangit.

It was Guglielmo Boccanegra who built the place, as the inscription reminds you,—it was his palace. But only the façade landward remains from his time, with the lions' heads, the great hall and the façade seaward dating from 1571, eleven years after Doria's death. In the tower is the old bell which used to summon the Grand Council; it is of seventeenth-century work, and was presented to the Bank by the Republic of Holland. [2]

Within, the palace is a ruin, only the Hall of Grand Council being in any way worth a visit. Here you may see statues of the chief benefactors of the city from the middle 25of the fourteenth century to the middle of the seventeenth. And by a curious device worthy of this city of merchants, each citizen got a statue according to his gifts. Those who save 100,000 lire were carved sitting there, while those who gave but half this were carved standing; less rich and less liberal benefactors got a bust or a mere commemorative stone, each according to his liberality, and this (strangely we may think), in a city so religious that it is dedicated to Madonna, might seem to leave nothing for the widow with her mite who gave more than they all.

One comes out of that dirty and ruined place, that was once so splendid, with a regret that modern Italy, which is so eager to build grandiose banks and every sort of public building, is yet so regardless of old things that one might fancy her history only began in 1860. Mr. Le Mesurier, in the interesting book already referred to, has suggested that this old palace, so full of memories of Genoa's greatness, should be used by the municipality as a museum for Genoese antiquities. I should like to raise my voice with his in this cause so worthy of the city we have loved. Is it still true of her, that though she is proud she is not proud enough? Is it to be said of her who sped Garibaldi on his first adventure, that all her old glory is forgotten, that she is content with mere wealth, a thing after all that she is compelled to share with the latest American encampment, in which competition she cannot hope to excel? But she who holds in her hands the dust of St. John Baptist, who has seen the cup of the Holy Grail, whose sons stormed Jerusalem and wept beside the Tomb of Jesus, through whose streets the bitter ashes of Augustine have passed, and in whose heart Columbus was conceived, and a great Admiral and a great Saint, is worthy of remembrance. Let her gather the beautiful or curious remnants of her great days about her now in the day of small things, that out of past splendour new glory may rise, for she also has ancestors, and, like the sun, which shall rise to-morrow, has known splendour of old.

As you leave the Banca di S. Giorgio, if you continue on 26your way you will come on to the great ramparts, where you may see the sea, and so you will leave Genoa behind you; but if, returning a little on your way, you turn into the Piazza Banchi, you will be really in the heart of the old city, in front of the sixteenth-century Exchange, Loggia dei Banchi, where Luca Pinelli was crucified for opposing a Fregoso Doge who wished to sell Livorno to Florence. Passing thence into the street of the jewellers, Strada degli Orefici, where every sort of silver filigree work may be found, with coral and amber, you come to Madonna of the Street Corner, a Virgin and Child, with S. Lo, the patron of all sorts of smiths, a seventeenth-century work of Piola. These narrow shadowy ways full of men and women and joyful with children are the delight of Genoa. There is but little to see, you may think,—little enough but just life. For Genoa is not a museum: she lives, and the laughter of her children is the greatest of all the joyful poems of Italy, maybe the only one that is immortal.

With this thought in your heart (as it is sure to be everywhere in Italy) you return (as one continually does) to the Arcades, and turning to the left you follow them till you come to Via S. Lorenzo, in which is the Duomo all of white and black marble, a jewel with mystery in its heart, hidden away among the houses of life.

It was built on the site of a church which commemorated the passing of S. Lorenzo through Genoa. Much of the present church is work of the twelfth century, such as the side doors and the walls, but the façade was built early in the fourteenth century, while the tower and the choir were not finished till 1617. The dome was made by Galeazzo Alessi, the Perugian who built so much in Genoa, as we shall see later. Possibly the bas-reliefs strewn on the north wall are work of the Roman period, but they are not of much interest save to an archeologist.

Within, the church is dark, and this I think is a disappointment, nor is it very rich or lovely. Some work of Matteo Civitali is still to be seen in a side chapel on the left, but the only remarkable thing in the church itself is the 27chapel of St. John Baptist, into which no woman may enter, because of the dancing of Salome, daughter of Herodias. There in a marble urn the ashes of the Messenger have lain for eight centuries, not without worship, for here have knelt Pope Alexander III, our own Richard Cordelion, Federigo Barbarossa, Henry IV after Canossa, Innocent IV, fugitive before Federigo II, Henry VII of Germany, St. Catherine of Siena, and often too, St. Catherine Adorni, Louis XII of France, Don John of Austria after Lepanto, and maybe, who knows, Velasquez of Spain, Vandyck from England, and behind them, all the misery of Genoa through the centuries, an immense and pitiful company of men and women crying in the silence to him who had cried in the wilderness.

Other curious, strange, and wonderful things, too, S. Lorenzo holds for us in her treasury: a piece of the True Cross set in a cruciform casket of gold crusted with precious stones, stolen, as most relics have been, this one from the Venetians in the fourth Crusade, when the Emperor Baldwin, whom Venice had crowned, sent it as gift to Pope Innocent III by a Venetian galley, which, caught in a storm, took shelter in Modone in Hellas, where two Genoese galleys found her and, having looted her, sent the relic to S. Lorenzo in Genoa magnanimously, as Giustiniani says. Here also beside this wonder you may see the cup of the Holy Grail, stolen by the French, who, forced to return it, sent this broken green glass in place of the perfect emerald they carried away; or maybe, who knows, it was but glass in the beginning. Yet, indeed, the Genoese paid a great price for it, thinking it truly the emerald of the Precious Blood, but they may have deceived themselves in the joy that followed the winning of the Holy City: though that is not like Genoa. However this may be, and with relics you are as like to be right as wrong whatever your opinion, there is but little else worth seeing in S. Lorenzo.

As you follow the Via S. Lorenzo upwards, you come presently on your left to the Piazza Umberto Primo, in which is the Palazzo Ducale, the ancient palace of the Doges, 28rebuilt finally in 1777; and at last, still ascending, you find yourself in the great shapeless Piazza Deferrari, with its statue to Garibaldi, while at the top of the Via S. Lorenzo on your right is the Church of S. Ambrogio, built by Pallavicini, with three pictures, a Guido Reni, the Assumption of the Virgin, and two Rubens, the Circumcision and S. Ignatius healing a madman. Not far away (for you turn into Piazza Deferrari and take the second street to the left, Strada S. Matteo) is the great Doria Church of S. Matteo, in black and white marble, a sort of mausoleum of the Doria family. Now, the family of Doria, one of the most ancient in Genoa, the Spinola clan alone being older, emerges really about 1100, and takes its rise, we are told, from Arduin, a knight of Narbonne, who, resting in Genoa on his way to Jerusalem, married Oria, a daughter of the Genoese house of della Volta. However this may be, in 1125 a certain Martino Doria founded the Church of S. Matteo, which has since remained the burial-place and monument of his race. Martino Doria is said to have become a monk, and to have died in the monastery of S. Fruttuoso at Portofino, where, too, lie many of the Doria family; but certainly as early as 1298 S. Matteo became the monument of the Doria greatness, for Lamba Doria, the victor of Curzola, where he beat the Venetian fleet, was laid here, as you may see from the inscription on the old sarcophagus at the foot of the façade of the church to the right. The façade itself is covered with inscriptions in honour of various members of the family: first, to Lamba, with an account of the battle. It reads as follows: "To the glory of God and the Blessed Virgin Mary, in the year 1298, on Sunday 7 September, this angel was taken in Venetian waters in the city of Curzola, and in that place was the battle of 76 Genoese galleys with 86 Venetian galleys, of which 84 were taken by the noble Lord Lamba Doria, then Captain and Admiral of the Commune and of the People of Genoa, with the men on them, of which he brought back to Genoa alive as prisoners 7400, along with 18 galleys, and the other 66 he caused to be burnt in the said Venetian waters,—he 29died at Savona in 1323." [3] It was in this engagement that Marco Polo was taken prisoner and brought to Genoa.

The second inscription on this façade refers to the battle of Sapienza, when in 1354 Pagano Doria beat the Venetians off the coast of Greece. It reads as follows: [4] "In honour of God and the Blessed Mary. In the fourth day of November 1354, the noble Lord Pagano Doria with 31 Genoese galleys, at the Island of Sapienza, fought and took 36 Venetian galleys and four ships, and led to Genoa 1400 men alive as captives with their captain."

The third inscription deals again with a defeat of the Venetian fleet, by Luciano Doria in 1379. It reads as follows: [5] "To the glory of God and the Blessed Mary. In the year 1379, on the 5th day of May, in the Gulf of the Venetians near Pola, there was a battle of 22 Genoese galleys with 22 galleys of the Venetians, in which were 4075 men-at-arms and many other men from Pola; of which galleys 16 were taken with all that was in them by the noble Lord Luciano Doria, Captain General of the Commune of Genoa, who in the said battle while fighting valiantly met his death. The sixteen galleys of the Venetians were conducted into Genoa with 2407 captive men."

The fourth inscription refers to the earlier victory of Oberto Doria over the Pisans. It is as follows: [6] "In the name of the Holy Trinity, in the year of Our Lord 1284, on the 6th day of August, the high and mighty Lord Oberto Doria, at that time Captain and Admiral of the Commune and of the Genoese people, triumphed in the Pisan waters over the Pisans, taking from them 33 galleys with 7 sunk and all the rest put to flight, and with many dead men left in the waters; and he returned to Genoa with a great multitude of captives, so that 7272 were placed in the prisons. There was taken 30Andrea Morosini of Venice, then Podestà and Captain General in war of the Commune of Pisa, with the standard of the Commune, captured by the galleys of Doria and brought to this church with the seal of the Commune, and there was also taken Loto, the son of Count Ugolino, and a great part of the Pisan nobility."

The fifth inscription refers to the victory of Filippino Doria, nephew to the great Admiral over the Spanish galleys in the Gulf of Salerno, which led Andrea, to the consternation of Genoa, to attack the Pope's galleys at Civitavecchia.

Within, the church was altered in 1530 by Montorsoli, the Florentine who was brought from Florence by the Admiral. And there above the high altar hangs his sword, given him by Pope Paul III, his friend and enemy. There, too, in the left aisle is the Doria chapel, with a picture of Andrea and his wife kneeling before our Lord. In the crypt, which was decorated in stucco by Montorsoli, you may see his tomb.

The beautiful cloister contains the statues of Andrea and Giovandrea, broken by the people in 1797. Close by is the Doria Palace, given by the Republic to Andrea when he refused the office of Doge. It is decorated with the privileged black and white marble, and bears the inscription, Senat. Cons. Andreae de Oria Patriae Liberatori Munus Publicium.

If you return from S. Matteo to the Piazza Deferrari and then follow the Via Carlo Felice (and without some sort of guidance such as this you are like to be lost in the maze of the city) on your way to the beautiful Piazza Fontane Marose, you pass on your left the Palazzo Pallavicini, empty now of all its treasures.

On your right as you enter this square of palaces is the Palazzo della Casa, once the Palazzo Spinola, decorated with the black and white marble, built in the early part of the fifteenth century, in the place where the old tower of that great family once stood. It is the palace of the oldest 31Genoese family, and the statues in the façade represent the most famous members of the clan, as Oberto, the son of the founder of this branch of the race, the Luccoli Spinola, Conrado, who ruled the city in 1206, and Opizino, who married his daughter to Theodore Paleologus, Emperor of Constantinople, and lived like a king and was banished in 1309. The palace itself is said to have been built with the remains of the Fieschi palace which the Senate destroyed in 1336. Beyond it rise the Palazzo Negrone and the Palazzo Pallavicini, while opposite the Negrone Palace the Via Nuova, now called Via Garibaldi (for the Italians have a bad habit of renaming their old streets), opens, a vista of palaces, where all the greatness and splendour of Genoa rise up before you in houses of marble, and courtyards musical with fountains, walls splendid with frescoes, and rooms full of pictures.

Before passing into this street of palaces, however, the traveller should follow the difficult Salita di S. Caterina, which climbs between Palazzo della Casa and Palazzo Negrone towards the Acqua Sola, that lovely garden, passing on his way the old Palazzo Spinola, where many an old and precious canvas still hangs on the walls, and the spoiled frescoes of the beautiful portico are fading in the sun.

It is perhaps in the Via Garibaldi, Via Cairoli, and Via Balbi, avenues of palaces narrow because of the summer sun, bordered on either side by triumphant slums, that the real Genoa splendid and living may best be surprised. Here, amid all the grave and yet homely magnificence of the princes of the State, life, with a brilliance and a misery all its own, ebbs and flows, and is not to be denied. Between two palaces of marble, silent, and full maybe of the masterpieces of dead painters, you may catch sight of the city of the people, a "truogolo" perhaps with a great fountain in the midst, where the girls and women are washing clothes, and the children, whole companies of them, play about the doorways, while above, the houses, and indeed the court itself, are bright with coloured cloths and linen drying in the wind and the sun. It is a city like London that you discover, 32living fiercely and with all its might, but without the brutality of our more terrible life, where as here wealth rises up in the midst of poverty, only here wealth is noble and without the blatancy and self-satisfaction you find in our squares, and poverty has not lost all its joyfulness, its air of simplicity and romance, as it has with us.

It is these palaces, so noble and, as one might think, so deserted, that Galeazzo Alessi built in the sixteenth century for the nobles of Genoa. And it is his work, whole streets of it, that has named the city the City of Palaces, as we say, and has given her something of that proud look which clings to her in her title, La Superba. Yet not altogether from the magnificence of her old streets has this name come to her, but in part from the character of her people, and in great measure, too, from her brave position there between the mountains and the sea, a city of precious stone in an amphitheatre of noble hills. Nothing that Genoa could build, steal, or win could even be so splendid as that birthright of hers, her place among the mountains on the shores of the great sea.

As one enters Via Garibaldi from Piazza Marose down the vistaed street where a precious strip of the blue sky seems more lovely for the shadowy way, the first house on the right is Palazzo Cambiaso, built by Alessi, while on the left, No. 2, is Palazzo Gambaro, which belonged to the Cambiaso family. No. 3 on the right is Palazzo Parodi, another of Alessi's works, built in 1567 for Franco Lercaro; No. 4 is Palazzo Carega; No. 5, Palazzo Spinola, again by Alessi; while Palazzo Giorgio Doria, No. 6, was also built by him. Here, beside frescoes by the Genoese Luca Cambiaso, you may find a Vandyck, a portrait of a lady and a Sussanah by Veronese. In the Palazzo Adorno too, No. 10, the work of Alessi, you may find several fine pictures, among them three trionfi in the manner of Botticelli, and a Rubens; while in Palazzo Serra, No. 12, but you may not enter, there is a fine hall. The Palazzo Municipale, built by Rocco Lurago at the end of the sixteenth century, has five frescoes 33of the life of the Doge Grimaldi, and Paganini's violin, a Guarnerius, on which Señor Sarasate played not long ago.

It is, however, in Palazzo Rosso, No. 18, possibly a work of Alessi's, that you may see what these Genoese palaces really are, for the Marchesa Maria Brignole-Sale, to whom it belonged, presented it to the city in 1874. It is into a vestibule, desolate enough certainly, that you pass out of the life of the street, and, ascending the great bare staircase, come at last on the third storey into the picture gallery. There is after all, but little to see; for, splendid though some of the pictures may once have been, they are now for the most part ruined. There remains, however, a Moretto, the portrait of a Physician, and the portrait of the Marchese Antonio Giulio Brignole-Sale on horseback, the beautiful work of Vandyck. Looking at this picture and its fellow, the portrait of the Marchesa, it is with sorrow we remember the fate that has befallen so many of Vandyck's masterpieces painted in this city. For either they have been carried away, like the magnificent group of the Lommellini family to Edinburgh, the Marchesa Brignole with her child to England, or they have been repainted and spoiled.

It was in 1621, on the 3rd October, that Vandyck, mounted on "the best horse in Rubens' stables," set out from Antwerp for Italy. After staying a short while in Brussels, he journeyed without further delay across France to Genoa. With him came Rubens' friend, Cavaliere Giambattista Nani. He reached Genoa on 20th November, where his friends of the de Wael family greeted him.

The city of Genoa, herself without a school of painting, had welcomed Rubens not long before very gladly, nor had Vandyck any cause to complain of her ingratitude. He appears to have set himself to paint in the style of Rubens, choosing similar subjects, at any rate, and thus to have won for himself, with such work as the Young Bacchantes, now in Lord Belper's collection, or the Drunken Silenus, now in Brussels, a reputation but little inferior to his master's. Certainly at this time his work is very Flemish in character, 34and apparently it was not till he had been to Venice, Mantua, and Rome that the influence of Italy and the Italian masters may be really found in his work. A disciple of Titian almost from his youth, it is the work of that master which gradually emancipates him from Flemish barbarism, from a too serious occupation with detail, the over-emphasis of northern work, the mere boisterousness, without any real distinction, that too often spoils Rubens for us, and yet is so easily excused and forgotten in the mere joy of life everywhere to be found in it. Well, with this shy and refined mind Italy is able to accomplish her mission; she humanises him, gives him the Latin sensibility and clarity of mind, the Latin refinement too, so that we are ready to forget he was Rubens' country-man, and think of him often enough as an Englishman, endowed as he was with much of the delicate and lovely genius of so many of our artists, full of a passionate yet shy strength, that some may think is the result of continual communion with Latin things, with Italy and Italian work, Italian verse, Italian painting, on the part of a race not Latin, but without the immobility, the want of versatility, common to the Germans, which has robbed them of any great painter since the early Renaissance, and in politics has left them to be the last people of Europe to win emancipation.

Much of this enlightening effect that Italy has upon the northerner may be found in the work of Vandyck on his return to Genoa, really a new thing in the world, as new as the poetry of Spenser had been, at any rate, and with much of his gravity and sweet melancholy or pensiveness, in those magnificent portraits of the Genoese nobility which time and fools have so sadly misused. And as though to confirm us in this thought of him, we may see, as it were, the story of his development during this journey to the south in the sketch-book in the possession of the Duke of Devonshire. Here, amid any number of sketches, thoughts as it were that Titian has suggested, or Giorgione evoked, we see the very dawn of all that we have come to consider as especially his own. We may understand how the pride and boisterous 35magnificence of Rubens came to seem a little insistent a little stupid too, beside Leonardo's Virgin and Child with St. Anne now in the Louvre, which he notes in Milan, or that Last Supper which is now but a shadow on the wall of S. Maria delle Grazie. And above all, we may see how the true splendour of Titian exposes the ostentation of Rubens, as the sun will make even the greatest fire look dingy and boastful. Gradually Vandyck, shy and of a quiet, serene spirit, becomes aware of this, and, led by the immeasurable glory of the Venetians, slowly escapes from that "Flemish manner" to be master of himself; so that, after he has painted in the manner of Titian at Palermo, he returns to Genoa to begin that wonderful series of masterpieces we all know, in which he has immortalised the tragedy of a king, the sorrowful beauty, frail and lovely as a violet, of Henrietta Maria, and the fate of the Princes of England. And though many of the pictures he painted in Genoa are dispersed, and many spoiled, some few remain to tell us of his passing. One, a Christ and the Pharisees, is in the Palazzo Bianco, not far from Palazzo Rosso, on the opposite side of the Via Garibaldi. But here there is a fine Rubens too; a Gerard David, very like the altar-piece at Rouen; a good Ruysdael, with some characteristic Spanish pictures by Zurbaran, Ribera, and Murillo; and while the Italian pictures are negligible, though some paintings and drawings of the Genoese school may interest us in passing, it is characteristic of Genoa that our interest in this collection should be with the foreign work there.

As you leave Via Garibaldi and pass down Via Cairoli, on your left you pass Via S. Siro. Turning down this little way, you come almost immediately to the Church of S. Siro. The present building dates from the seventeenth century, but the old church, then called Dei Dodici Apostoli, was the Cathedral of Genoa. It was close by that the blessed Sirus "drew out the dreadful serpent named Basilisk in the year 550." What this serpent may really have been no one knows, but Carlone has painted the scene in fresco in S. Siro.

Returning to Via Cairoli, at the bottom, in Piazza 36Zecca on your left, is one of the Balbi palaces; while in Piazza Annunziata, a little farther on, you come to the beautiful Church of Santissima Annunziata del Vastato, built by Della Porta in 1587.

Crossing this Piazza, you enter perhaps the most splendid street in Genoa, Via Balbi, which climbs up at last to the Piazza Acquaverde, the Statue of Columbus, and the Railway. The first palace on your right is Palazzo Durazzo-Pallavicini, with a fine picture gallery. Here you may see two fine Rubens, a portrait of Philip IV of Spain, and a Silenus with Bacchantes, a great picture of James I of England with his family, painted by some "imitator" of Vandyck, though who it was in Genoa that knew both Vandyck and England is not yet clear; a Ribera, a Reni, a Tintoretto, a Domenichino, and above all else Vandyck's Boy in White Satin, in the midst of these ruined pictures which certainly once would have given us joy. The Boy in White Satin is perhaps the loveliest picture Vandyck left behind him; though it is but partly his after all, the fruit, the parrot, and the monkey being the work of Snyders.

On the other side of the Via Balbi, almost opposite the Palazzo Durazzo-Pallavicini, is the Palazzo Balbi, which possesses the loveliest cortile in Genoa, with an orange garden, and in the Great Hall a fine gallery of pictures. Here is the Vandyck portrait of Philip II of Spain, which Velasquez not only used as a model, or at least remembered when he painted his equestrian Olivarez in the Prado, but which he changed, for originally it was a portrait of Francesco Maria Balbi, till, as is said, Velasquez came and painted there the face of Philip II. Certainly Velasquez may have sketched the picture and used it later, but it seems unlikely that he would have painted the face of Philip II, whom he had never seen, though the Genoese at that time might well have asked him to do so. [7]

As you continue on your way up Via Balbi, you have on your right the Palazzo dell' Università, with its magnificent 37staircase built in 1623 by Bartolommeo Bianco. Some statues by Giovanni da Bologna make it worth a visit, while of old the tomb of Simone Boccanegra, the great Doge, made such a visit pious and necessary.

Opposite the University is the Palazzo Reale, which once belonged to the Durazzo family. A crucifixion by Vandyck is perhaps not too spoiled to be still called his work.

So at last you will come to the Piazza Acquaverde and the Statue of Columbus, which is altogether dwarfed by the Railway Station. Not far away to the left, behind this last, you will find the great Palazzo Doria. It is almost nothing now, but in John Evelyn's day, when accompanied by that "most courteous marchand called Tornson," he went to see "the rarities," it was still full of its old splendour. "One of the greatest palaces here for circuit," he writes, "is that of the Prince d'Orias, which reaches from the sea to the summit of the mountaines. The house is most magnificently built without, nor less gloriously furnished within, having whole tables and bedsteads of massy silver, many of them sett with achates, onyxes, cornelians, lazulis, pearls, turquizes, and other precious stones. The pictures and statues are innumerable. To this palace belong three gardens, the first whereof is beautified with a terrace supported by pillars of marble; there is a fountaine of eagles, and one of Neptune, with other sea-gods, all of the purest white marble: they stand in a most ample basine of the same stone. At the side of this garden is such an aviary as S^r. Fra. Bacon describes in his Sermones Fidelium or Essays, wherein grow trees of more than two foote diameter, besides cypresse, myrtils, lentiscs, and other rare shrubs, which serve to nestle and pearch all sorts of birds, who have an ayre and place enough under their ayrie canopy, supported with huge iron worke stupendious for its fabrick and the charge. The other two gardens are full of orange trees, citrons, and pomegranates; fountaines, grotts, and statues; one of the latter is a colossal Jupiter, under which is a sepulchre of a beloved dog, for the care of which one of this family receiv'd of the K. of Spayne 500 crownes a yeare 38during the life of the faithful animal. The reservoir of water here is a most admirable piece of art; and so is the grotto over against it."

Close by Palazzo Doria is the Church of S. Giovanni di Prè, with its English tomb and Lombard tower, and memories of the two Urban popes Urban V and Urban VI, the first of whom stayed here on his way back to Rome from the Babylonian captivity, while the other murdered eight of his Cardinals close by, and threw their bodies into the sea. This is the quarter of booty, the booty of the Crusaders, and it is in such a place and in the older part of the town near Piazza Sarzano and in the narrow ways behind the Exchange that, as I think, Genoa seems most herself, the port of the Mediterranean, the gate of Italy. Yet what I prefer in Genoa are her triumphant slums, then the palaces and villas with their bigness, so impressive for us who came from the North, which seem to be a remnant of Roman greatness, a vision as it were of solidity and grandeur. Something of this, it is true, haunts almost every Italian city; only nowhere but in Genoa can you see so many palaces together, whole streets of them, huge, overwhelming, and yet beautiful houses, that often seem deserted, as though they belonged to a greater and more splendid age than ours.