The Project Gutenberg EBook of Some Account of the Life of Mr. William Shakespear (1709), by Nicholas Rowe This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Some Account of the Life of Mr. William Shakespear (1709) Author: Nicholas Rowe Commentator: Samuel H. Monk Release Date: July 12, 2005 [EBook #16275] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MR. WILLIAM SHAKESPEAR *** Produced by David Starner, Louise Pryor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

No. 1

With an Introduction by

Samuel H. Monk

The Augustan Reprint Society

November, 1948

Price. One Dollar

GENERAL EDITORS

Richard C. Boys, University of Michigan

Edward Niles Hooker, University of California, Los Angeles

H.t. Swedenberg, Jr., University of California, Los Angeles

ASSISTANT EDITOR

W. Earl Britton, University of Michigan

ADVISORY EDITORS

Emmett L. Avery, State College of Washington

Benjamin Boyce, University of Nebraska

Louis I. Bredvold, University of Michigan

Cleanth Brooks, Yale University

James L. Clifford, Columbia University

Arthur Friedman, University of Chicago

Samuel H. Monk, University of Minnesota

Ernest Mossner, University of Texas

James Sutherland, Queen Mary College, London

Lithoprinted from copy supplied by author

by

Edwards Brothers, Inc.

Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A.

1948

The Rowe-Tonson edition of Shakespeare's plays (1709) is an important event in the history of both Shakespeare studies and English literary criticism. Though based substantially on the Fourth Folio (1685), it is the first, "edited" edition: Rowe modernized spelling and punctuation and quietly made a number of sensible emendations. It is the first edition to include dramatis personae, the first to attempt a systematic division of all the plays into acts and scenes, and the first to give to scenes their distinct locations. It is the first of many illustrated editions. It is the first to abandon the clumsy folio format and to attempt to bring the plays within reach of the understanding and the pocketbooks of the average reader. Finally, it is the first to include an extended life and critique of the author.

Shakespeare scholars from Pope to the present have not been kind to Rowe either as editor or as critic; but all eighteenth-century editors accepted many of his emendations, and the biographical material that he and Betterton assembled remained the basis of all accounts of the dramatist until the scepticism and scholarship of Steevens and Malone proved most of it to be merely dubious tradition. Johnson, indeed, spoke generously of the edition. In the Life of Rowe he said that as an editor Howe "has done more than he promised; and that, without the pomp of notes or the boast of criticism, many passages are happily restored." The preface, in his opinion, "cannot be said to discover much profundity or penetration." But he acknowledged Rowe's influence on Shakespeare's reputation. In our own century, more justice has been done Rowe, at least as an editor.[1]

The years 1709-14 were of great importance in the growth of Shakespeare's reputation. As we shall see, the plays as well as the poems, both authentic and spurious, were frequently printed and bought. With the passing of the seventeenth-century folios and the occasional quartos of acting versions of single plays, Shakespeare could find a place in libraries and could be intimately known by hundreds who had hitherto known him only in the theater. Tonson's business acumen made Shakespeare available to the general reader in the reign of Anne; Rowe's editorial, biographical, and critical work helped to make him comprehensible within the framework of contemporary taste.

When Rowe's edition appeared twenty-four years had passed since the publication of the Fourth Folio. As Allardyce Nicoll has shown, Tonson owned certain rights in the publication of the plays, rights derived ultimately from the printers of the First Folio. Precisely when he decided to publish a revised octavo edition is not known, nor do we know when Rowe accepted the commission and began his work. McKerrow has plausibly suggested that Tonson may have been anxious to call attention to his rights in Shakespeare on the eve of the passage of the copyright law which went into effect in April, 1710.[2] Certainly Tonson must have felt that he was adding to the prestige which his publishing house had gained by the publication of Milton and Dryden's Virgil.

In March 1708/9 Tonson was advertising for materials "serviceable to [the] Design" of publishing an edition of Shakespeare's works in six volumes octavo, which would be ready "in a Month." There was a delay, however, and it was on 2 June that Tonson finally announced: "There is this day Publish'd ... the Works of Mr. William Shakespear, in six Vols. 8vo. adorn'd with Cuts, Revis'd and carefully Corrected: With an Account of the Life and Writings of the Author, by N. Rowe, Esq; Price 30s." Subscription copies on large paper, some few to be bound in nine volumes, were to be had at his shop.[3]

The success of the venture must have been immediately apparent. By 1710 a second edition, identical in title page and typography with the first, but differing in many details, had been printed,[4] followed in 1714 by a third in duodecimo. This so-called second edition exists in three issues, the first made up of eight volumes, the third of nine. In all three editions the spurious plays were collected in the last volume, except in the third issue of 1714, in which the ninth volume contains the poems.

That other publishers sensed the profits in Shakespeare is evident from the activities of Edmund Curll and Bernard Lintot. Curll acted with imagination and promptness: within three weeks of the publication of Tonson's edition, he advertised as Volume VII of the works of Shakespeare his forthcoming volume of the poems. This volume, misdated 1710 on the title page, seems to have been published in September 1709. A reprint with corrections and some emendations of the Cotes-Benson Poems Written By Wil. Shake-speare. Gent., 1640, it contains Charles Gildon's "Essay on the Art, Rise, and Progress of the Stage in Greece, Rome, and England," his "Remarks" on the separate plays, his "References to Classic Authors," and his glossary. With great shrewdness Curll produced a volume uniform in size and format with Rowe's edition and equipped with an essay which opens with an attack on Tonson for printing doubtful plays and for attempting to disparage the poems through envy of their publisher. This attack was certainly provoked by the curious final paragraph of Rowe's introduction, in which he refused to determine the genuineness of the 1640 poems. Obviously Tonson was perturbed when he learned that Curll was publishing the poems as an appendix to Rowe's edition.

Once again a Shakespearian publication was successful, and Tonson incorporated the Curll volume into the third issue of the 1714 edition, having apparently come to some agreement with Curll, since the title page of Volume IX states that it was "Printed for J. Tonson, E. Curll, J. Pemberton, and K. Sanger." In this edition Gildon omitted his offensive remarks about Tonson, as well as the "References to Classic Authors," in which he had suggested topics treated by both the ancients and Shakespeare. This volume was revised by George Sewell and appeared in appropriate format as an addition to Pope's Shakespeare, 1723-25.

Meanwhile, in July, 1709, Lintot had begun to advertise his edition of the poems, which was expanded in 1710/11 to include the sonnets in a second volume.[5] Thus within a year of the publication of Rowe's edition, all of Shakespeare, as well as some spurious works, was on the market. With the publication of these volumes, Shakespeare began to pass rapidly into the literary consciousness of the race. And formal criticism of his writings inevitably followed.

Rowe's "Some Account of the Life, &c. of Mr. William Shakespear," reprinted with a very few trifling typographical changes in 1714, survived in all the important eighteenth-century editions, but it was never reprinted in its original form. Pope re-arranged the material, giving it a more orderly structure and omitting passages that were obviously erroneous or that seemed outmoded.[6] It is odd that all later eighteenth-century editors seem to have believed that Pope's revision was actually Rowe's own re-writing of the Account for the 1714 edition. Theobald did not reprint the essay, but he used and amplified Rowe's material in his biography of Shakespeare; Warburton, of course, reprinted Pope's version, as did Johnson, Steevens, and Malone. Both Steevens and Malone identified the Pope revision as Rowe's.[7]

Thus it came about that Rowe's preface in its original form was lost from sight during the entire eighteenth century. Even in the twentieth, Pope's revision has been printed with the statement that it is taken "from the second edition (1714), slightly altered from the first edition of 1709."[8] Only D. Nichol Smith has republished the original essay in his Eighteenth Century Essays on Shakespeare, 1903.

The biographical part of Rowe's Account assembled the few facts and most of the traditions still current about Shakespeare a century after his death. It would be easy for any undergraduate to distinguish fact from legend in Rowe's preface; and scholarship since Steevens and Malone has demonstrated the unreliability of most of the local traditions that Betterton reported from Warwickshire. Antiquarian research has added a vast amount of detail about the world in which Shakespeare lived and has raised and answered questions that never occurred to Rowe; but it has recovered little more of the man himself than Rowe knew.

The critical portions of Rowe's account look backward and forward: backward to the Restoration, among whose critical controversies the eighteenth-century Shakespeare took shape; and forward to the long succession of critical writings that, by the end of the century, had secured for Shakespeare his position as the greatest of the English poets. Until Dryden and Rymer, criticism of Shakespeare in the seventeenth century had been occasional rather than systematic. Dryden, by his own acknowledgement, derived his enthusiasm for Shakespeare from Davenant, and thus, in a way, spoke for a man who had known the poet. Shakespeare was constantly in his mind, and the critical problems that the plays raised in the literary milieu of the Restoration constantly fascinated him. Rymer's attack served to solidify opinion and to force Shakespeare's admirers to examine the grounds of their faith. By 1700 a conventional manner of regarding Shakespeare and the plays had been achieved.

The growth of Shakespeare's reputation during the century after his death is a familiar episode in English criticism. Bentley has demonstrated the dominant position of Jonson up to the end of the century.[9] But Jonson's reputation and authority worked for Shakespeare and helped to shape, a critical attitude toward the plays. His official praise in the first Folio had declared Shakespeare at least the equal of the ancients and the very poet of nature. He had raised the issue of Shakespeare's learning, thus helping to emphasize the idea of Shakespeare as a natural genius; and in the Discoveries he had blamed his friend for too great facility and for bombast.

In his commendatory sonnet in the Second Folio (1632), Milton took the Jonsonian view of Shakespeare, whose "easy numbers" he contrasted with "slow-endeavouring Art," and readers of the poems of 1645 found in L'Allegro an early formulation of what was to become the stock comparison of the two great Jacobean dramatists in the lines about Jonson's "learned sock" and Shakespeare, "Fancy's child." This contrast became a constant theme in Restoration allusions to the two poets.

Two other early critical ideas were to be elaborated in the last four decades of the century. In the first Folio Leonard Digges had spoken of Shakespeare's "fire and fancy," and I.M.S. had written in the Second Folio of his ability to move the passions. Finally, throughout the last half of the century, as Bentley has shown, Shakespeare was admired above all English dramatists for his ability to create characters, of whom Falstaff was the most frequently mentioned.

All of these opinions were developed in Dryden's frequent critical remarks on his favorite dramatist. No one was more clearly aware than he of the faults of the "divine Shakespeare" as they appeared in the new era of letters that Dryden himself helped to shape. And no man ever praised Shakespeare more generously. For Dryden Shakespeare was the greatest of original geniuses, who, "taught by none," laid the foundations of English drama; he was a poet of bold imagination, especially gifted in "magick" or the supernatural, the poet of nature, who could dispense with "art," the poet of the passions, of varied characters and moods, the poet of large and comprehensive soul. To him, as to most of his contemporaries, the contrast between Jonson and Shakespeare was important: the one showed what poets ought to do; the other what untutored genius can do. When Dryden praised Shakespeare, his tone became warmer than when he judicially appraised Jonson.

Like most of his contemporaries Dryden did not heed Jonson's caveat that, despite his lack of learning, Shakespeare did have art. He was too obsessed with the idea that Shakespeare, ignorant of the health-giving art of the ancients, was infected with the faults of his age, faults that even Jonson did not always escape. Shakespeare was often incorrect in grammar; he frequently sank to flatness or soared into bombast; his wit could be coarse and low and too dependent on puns; his plot structure was at times faulty, and he lacked the sense for order and arrangement that the new taste valued. All this he could and did admit, and he was impressed by the learning and critical standards of Rymer's attack. But like Samuel Johnson he was not often prone to substitute theory for experience, and like most of his contemporaries he felt Shakespeare's power to move and to convince. Perhaps the most trenchant expression of his final stand in regard to Shakespeare and to the whole art of poetry is to be found in his letter to Dennis, dated 3 March, 1693/4. Shakespeare, he said, had genius, which is "alone a greater Virtue ... than all the other Qualifications put together." He admitted that all the faults pointed out by Rymer are real enough, but he added a question that removed the discussion from theory to immediate experience: "Yet who will read Mr. Rym[er] or not read Shakespear?" When Dryden died in 1700, the age of Jonson had passed and the age of Shakespeare was about to begin.

The Shakespeare of Rowe's Account is in most essentials the Shakespeare of Restoration criticism, minus the consideration of his faults. As Nichol Smith has observed, Dryden and Rymer were continually in Rowe's mind as he wrote. It is likely that Smith is correct in suspecting in the Account echoes of Dryden's conversation as well as of his published writings;[10] and the respect in which Rymer was then held is evident in Rowe's desire not to enter into controversy with that redoubtable critic and in his inability to refrain from doing so.

If one reads the Account in Pope's neat and tidy revision and then as Rowe published it, one is impressed with its Restoration quality. It seems almost deliberately modelled on Dryden's prefaces, for it is loosely organized, discursive, intimate, and it even has something of Dryden's contagious enthusiasm. Rowe presents to his reader the Restoration Shakespeare: the original genius, the antithesis of Jonson, the exception to the rule and the instance that diminishes the importance of the rules. Shakespeare "lived under a kind of mere light of nature," and knowing nothing of the rules should not be judged by them. Admitting the poor plot structure and the neglect of the unities, except in an occasional play, Rowe concentrates on Shakespeare's virtues: his images, "so lively, that the thing he would represent stands full before you, and you possess every part of it;" his command over the passions, especially terror; his magic; his characters and their "manners."

Bentley has demonstrated statistically that the Restoration had little appreciation of the romantic comedies. And yet Rowe, so thoroughly saturated with Restoration criticism, lists character after character from these plays as instances of Shakespeare's ability to depict the manners. Have we perhaps here a response to Shakespeare read as opposed to Shakespeare seen? Certainly the romantic comedies could not stand the test of the critical canons so well as did the Merry Wives or even Othello; and they were not much liked on the stage. But it seems probable that a generation which read French romances would not have felt especially hostile to the romantic comedies when read in the closet. Rowe's criticism is so little original, so far from idiosyncratic, that it is unnecessary to assume that his response to the characters in the comedies is unique.

Be that as it may, it was well that at the moment when the reading public began rapidly to expand in England, Tonson should have made Shakespeare available in an attractive and convenient format; and it was a happy choice that brought Rowe to the editorship of these six volumes. As poet, playwright, and man of taste, Rowe was admirably fitted to introduce Shakespeare to a multitude of new readers. Relatively innocent of the technical duties of an editor though he was, he none the less was capable of accomplishing what proved to be his historic mission: the easy re-statement of a view of Shakespeare which Dryden had earlier articulated and the demonstration that the plays could be read and admired despite the objections of formal dramatic criticism. He is more than a chronological predecessor of Pope, Johnson, and Morgann. The line is direct from Shakespeare to Davenant, to Dryden, to Rowe; and he is an organic link between this seventeenth-century tradition and the increasingly rich Shakespeare scholarship and criticism that flowed through the eighteenth century into the romantic era.

Notes

[1] Alfred Jackson, "Rowe's edition of Shakespeare," Library X (1930), 455-473; Allardyce Nicoll, "The editors of Shakespeare from first folio to Malone," Studies in the first Folio, London (1924), pp. 158-161; Ronald B. McKerrow, "The treatment of Shakespeare's text by his earlier editors, 1709-1768," Proceedings of the British Academy, XIX (1933), 89-122; Augustus Ralli, A history of Shakespearian criticism, London, 1932; Herbert S. Robinson, English Shakespearian criticism in the eighteenth century, New York, 1932.

[2] Nicoll, op. cit., pp. 158-161; McKerrow, op. cit., p. 93.

[3] London Gazette, From Monday March 14 to Thursday March 17, 1708, and From Monday May 30 to Thursday June 2, 1709. For descriptions and collations of this edition, see A. Jackson, op. cit.; H.L. Ford, Shakespeare 1700-1740, Oxford (1935), pp. 9, 10; TLS 16 May, 1929, p. 408; Edward Wagenknecht, "The first editor of Shakespeare," Colophon VIII, 1931. According to a writer in The Gentleman's Magazine (LVII, 1787, p. 76), Rowe was paid thirty-six pounds, ten shillings by Tonson.

[4] Identified and described by McKerrow, TLS 8 March, 1934, p. 168. See also Ford, op. cit., pp. 11, 12.

[5] The best discussion of the Curll and Lintot Poems is that of Hyder Rollins in A new variorum edition of Shakespeare: the poems, Philadelphia and London (1938) pp. 380-382, to which I am obviously indebted. See also Raymond M. Alden, "The 1710 and 1714 texts of Shakespeare's poems," MLN XXXI (1916), 268-274; and Ford, op. cit., pp. 37-40.

[6] For example, he dropped out Rowe's opinion that Shakespeare had little learning; the reference to Dryden's view as to the date of Pericles; the statement that Venus and Adonis is the only work that Shakespeare himself published; the identification of Spenser's "pleasant Willy" with Shakespeare; the account of Jonson's grudging attitude toward Shakespeare; the attack on Rymer and the defence of Othello; and the discussion of the Davenant-Dryden Tempest, together with the quotation from Dryden's prologue to that play.

[7] Edmond Malone, The plays and poems of William Shakespeare, London (1790), I, 154. Difficult as it is to believe that so careful a scholar as Malone could have made this error, it is none the less true that he observed the omission of the passage on "pleasant Willy" and stated that Rowe had obviously altered his opinion by 1714.

[8] Beverley Warner, Famous introductions to Shakespeare's plays, New York (1906), p. 6.

[9] Gerald E. Bentley, Shakespeare and Jonson, Chicago (1945). Vol. I.

[10] D. Nichol Smith, Eighteenth century essays on Shakespeare, Glasgow (1903), pp. xiv-xv.

The writer wishes to express his appreciation of a Research Grant from the University of Minnesota for the summer of 1948, during which this introduction was written.

—Samuel Holt Monk

University of Minnesota

WORKS

OF

Mr. William Shakespear;

IN

SIX VOLUMES.

ADORN'D with CUTS.

Revis'd and Corrected, with an Account of the Life and Writings of the Author.

By N. ROWE, Esq;

L O N D O N:

Printed for Jacob Tonson, within Grays-Inn Gate, next Grays-Inn Lane. MDCCIX.

ACCOUNT

OF THE

LIFE, &c.

OF

Mr. William Shakespear.

It seems to be a kind of Respect due to the Memory of Excellent Men, especially of those whom their Wit and Learning have made Famous, to deliver some Account of themselves, as well as their Works, to Posterity. For this Reason, how fond do we see some People of discovering any little Personal Story of the great Men of Antiquity, their Families, the common Accidents of their Lives, and even their Shape, Make and Features have been the Subject of critical Enquiries. How trifling soever this Curiosity may seem to be, it is certainly very Natural; and we are hardly satisfy'd with an Account of any remarkable Person, 'till we have heard him describ'd even to the very Cloaths he wears. As for what relates to Men of Letters, the knowledge of an Author may sometimes conduce to the better understanding his Book: And tho' the Works of Mr. Shakespear may seem to many not to want a Comment, yet I fancy some little Account of the Man himself may not be thought improper to go along with them.

He was the Son of Mr. John Shakespear, and was Born at Stratford upon Avon, in Warwickshire, in April 1564. His Family, as appears by the Register and Publick Writings relating to that Town, were of good Figure and Fashion there, and are mention'd as Gentlemen. His Father, who was a considerable Dealer in Wool, had so large a Family, ten Children in all, that tho' he was his eldest Son, he could give him no better Education than his own Employment. He had bred him, 'tis true, for some time at a Free-School, where 'tis probable he acquir'd that little Latin he was Master of: But the narrowness of his Circumstances, and the want of his assistance at Home, forc'd his Father to withdraw him from thence, and unhappily prevented his further Proficiency in that Language. It is without Controversie, that he had no knowledge of the Writings of the Antient Poets, not only from this Reason, but from his Works themselves, where we find no traces of any thing that looks like an Imitation of 'em; the Delicacy of his Taste, and the natural Bent of his own Great Genius, equal, if not superior to some of the best of theirs, would certainly have led him to Read and Study 'em with so much Pleasure, that some of their fine Images would naturally have insinuated themselves into, and been mix'd with his own Writings; so that his not copying at least something from them, may be an Argument of his never having read 'em. Whether his Ignorance of the Antients were a disadvantage to him or no, may admit of a Dispute: For tho' the knowledge of 'em might have made him more Correct, yet it is not improbable but that the Regularity and Deference for them, which would have attended that Correctness, might have restrain'd some of that Fire, Impetuosity, and even beautiful Extravagance which we admire in Shakespear: And I believe we are better pleas'd with those Thoughts, altogether New and Uncommon, which his own Imagination supply'd him so abundantly with, than if he had given us the most beautiful Passages out of the Greek and Latin Poets, and that in the most agreeable manner that it was possible for a Master of the English Language to deliver 'em. Some Latin without question he did know, and one may see up and down in his Plays how far his Reading that way went: In Love's Labour lost, the Pedant comes out with a Verse of Mantuan; and in Titus Andronicus, one of the Gothick Princes, upon reading

says, 'Tis a Verse in Horace, but he remembers it out of his Grammar: Which, I suppose, was the Author's Case. Whatever Latin he had, 'tis certain he understood French, as may be observ'd from many Words and Sentences scatter'd up and down his Plays in that Language; and especially from one Scene in Henry the Fifth written wholly in it. Upon his leaving School, he seems to have given intirely into that way of Living which his Father propos'd to him; and in order to settle in the World after a Family manner, he thought fit to marry while he was yet very Young. His Wife was the Daughter of one Hathaway, said to have been a substantial Yeoman in the Neighbourhood of Stratford. In this kind of Settlement he continu'd for some time, 'till an Extravagance that he was guilty of, forc'd him both out of his Country and that way of Living which he had taken up; and tho' it seem'd at first to be a Blemish upon his good Manners, and a Misfortune to him, yet it afterwards happily prov'd the occasion of exerting one of the greatest Genius's that ever was known in Dramatick Poetry. He had, by a Misfortune common enough to young Fellows, fallen into ill Company; and amongst them, some that made a frequent practice of Deer-stealing, engag'd him with them more than once in robbing a Park that belong'd to Sir Thomas Lucy of Cherlecot, near Stratford. For this he was prosecuted by that Gentleman, as he thought somewhat too severely; and in order to revenge that ill Usage, he made a Ballad upon him. And tho' this, probably the first Essay of his Poetry, be lost, yet it is said to have been so very bitter, that it redoubled the Prosecution against him to that degree, that he was oblig'd to leave his Business and Family in Warwickshire, for some time, and shelter himself in London.

It is at this Time, and upon this Accident, that he is said to have made his first Acquaintance in the Play-house. He was receiv'd into the Company then in being, at first in a very mean Rank; But his admirable Wit, and the natural Turn of it to the Stage, soon distinguish'd him, if not as an extraordinary Actor, yet as an excellent Writer. His Name is Printed, as the Custom was in those Times, amongst those of the other Players, before some old Plays, but without any particular Account of what sort of Parts he us'd to play; and tho' I have inquir'd, I could never meet with any further Account of him this way, than that the top of his Performance was the Ghost in his own Hamlet. I should have been much more pleas'd, to have learn'd from some certain Authority, which was the first Play he wrote; it would be without doubt a pleasure to any Man, curious in Things of this Kind, to see and know what was the first Essay of a Fancy like Shakespear's. Perhaps we are not to look for his Beginnings, like those of other Authors, among their least perfect Writings; Art had so little, and Nature so large a Share in what he did, that, for ought I know, the Performances of his Youth, as they were the most vigorous, and had the most fire and strength of Imagination in 'em, were the best. I would not be thought by this to mean, that his Fancy was so loose and extravagant, as to be Independent on the Rule and Government of Judgment; but that what he thought, was commonly so Great, so justly and rightly Conceiv'd in it self, that it wanted little or no Correction, and was immediately approv'd by an impartial Judgment at the first sight. Mr. Dryden seems to think that Pericles is one of his first Plays; but there is no judgment to be form'd on that, since there is good Reason to believe that the greatest part of that Play was not written by him; tho' it is own'd, some part of it certainly was, particularly the last Act. But tho' the order of Time in which the several Pieces were written be generally uncertain, yet there are Passages in some few of them which seem to fix their Dates. So the Chorus in the beginning of the fifth Act of Henry V. by a Compliment very handsomly turn'd to the Earl of Essex, shews the Play to have been written when that Lord was General for the Queen in Ireland: And his Elogy upon Q. Elizabeth, and her Successor K. James, in the latter end of his Henry VII, is a Proof of that Play's being written after the Accession of the latter of those two Princes to the Crown of England. Whatever the particular Times of his Writing were, the People of his Age, who began to grow wonderfully fond of Diversions of this kind, could not but be highly pleas'd to see a Genius arise amongst 'em of so pleasurable, so rich a Vein, and so plentifully capable of furnishing their favourite Entertainments. Besides the advantages of his Wit, he was in himself a good-natur'd Man, of great sweetness in his Manners, and a most agreeable Companion; so that it is no wonder if with so many good Qualities he made himself acquainted with the best Conversations of those Times. Queen Elizabeth had several of his Plays Acted before her, and without doubt gave him many gracious Marks of her Favour: It is that Maiden Princess plainly, whom he intends by

Midsummer Night's Dream,

Vol. 2. p. 480.

And that whole Passage is a Compliment very properly brought in, and very handsomly apply'd to her. She was so well pleas'd with that admirable Character of Falstaff, in the two Parts of Henry the Fourth, that she commanded him to continue it for one Play more, and to shew him in Love. This is said to be the Occasion of his Writing The Merry Wives of Windsor. How well she was obey'd, the Play it self is an admirable Proof. Upon this Occasion it may not be improper to observe, that this Part of Falstaff is said to have been written originally under the Name of Oldcastle; some of that Family being then remaining, the Queen was pleas'd to command him to alter it; upon which he made use of Falstaff. The present Offence was indeed avoided; but I don't know whether the Author may not have been somewhat to blame in his second Choice, since it is certain that Sir John Falstaff, who was a Knight of the Garter, and a Lieutenant-General, was a Name of distinguish'd Merit in the Wars in France in Henry the Fifth's and Henry the Sixth's Times. What Grace soever the Queen confer'd upon him, it was not to her only he ow'd the Fortune which the Reputation of his Wit made. He had the Honour to meet with many great and uncommon Marks of Favour and Friendship from the Earl of Southampton, famous in the Histories of that Time for his Friendship to the unfortunate Earl of Essex. It was to that Noble Lord that he Dedicated his Venus and Adonis, the only Piece of his Poetry which he ever publish'd himself, tho' many of his Plays were surrepticiously and lamely Printed in his Lifetime. There is one Instance so singular in the Magnificence of this Patron of Shakespear's, that if I had not been assur'd that the Story was handed down by Sir William D'Avenant, who was probably very well acquainted with his Affairs, I should not have ventur'd to have inserted, that my Lord Southampton, at one time, gave him a thousand Pounds, to enable him to go through with a Purchase which he heard he had a mind to. A Bounty very great, and very rare at any time, and almost equal to that profuse Generosity the present Age has shewn to French Dancers and Italian Eunuchs.

What particular Habitude or Friendships he contracted with private Men, I have not been able to learn, more than that every one who had a true Taste of Merit, and could distinguish Men, had generally a just Value and Esteem for him. His exceeding Candor and good Nature must certainly have inclin'd all the gentler Part of the World to love him, as the power of his Wit oblig'd the Men of the most delicate Knowledge and polite Learning to admire him. Amongst these was the incomparable Mr. Edmond Spencer, who speaks of him in his Tears of the Muses, not only with the Praises due to a good Poet, but even lamenting his Absence with the tenderness of a Friend. The Passage is in Thalia's Complaint for the Decay of Dramatick Poetry, and the Contempt the Stage then lay under, amongst his Miscellaneous Works, p. 147.

I know some People have been of Opinion, that Shakespear is not meant by Willy in the first Stanza of these Verses, because Spencer's Death happen'd twenty Years before Shakespear's. But, besides that the Character is not applicable to any Man of that time but himself, it is plain by the last Stanza that Mr. Spencer does not mean that he was then really Dead, but only that he had with-drawn himself from the Publick, or at least with-held his Hand from Writing, out of a disgust he had taken at the then ill taste of the Town, and the mean Condition of the Stage. Mr. Dryden was always of Opinion these Verses were meant of Shakespear; and 'tis highly probable they were so, since he was three and thirty Years old at Spencer's Death; and his Reputation in Poetry must have been great enough before that Time to have deserv'd what is here said of him. His Acquaintance with Ben Johnson began with a remarkable piece of Humanity and good Nature; Mr. Johnson, who was at that Time altogether unknown to the World, had offer'd one of his Plays to the Players, in order to have it Acted; and the Persons into whose Hands it was put, after having turn'd it carelessly and superciliously over, were just upon returning it to him with an ill-natur'd Answer, that it would be of no service to their Company, when Shakespear luckily cast his Eye upon it, and found something so well in it as to engage him first to read it through, and afterwards to recommend Mr. Johnson and his Writings to the Publick. After this they were profess'd Friends; tho' I don't know whether the other ever made him an equal return of Gentleness and Sincerity. Ben was naturally Proud and Insolent, and in the Days of his Reputation did so far take upon him the Supremacy in Wit, that he could not but look with an evil Eye upon any one that seem'd to stand in Competition with him. And if at times he has affected to commend him, it has always been with some Reserve, insinuating his Uncorrectness, a careless manner of Writing, and want of Judgment; the Praise of seldom altering or blotting out what he writ, which was given him by the Players who were the first Publishers of his Works after his Death, was what Johnson could not bear; he thought it impossible, perhaps, for another Man to strike out the greatest Thoughts in the finest Expression, and to reach those Excellencies of Poetry with the Ease of a first Imagination, which himself with infinite Labour and Study could but hardly attain to. Johnson was certainly a very good Scholar, and in that had the advantage of Shakespear; tho' at the same time I believe it must be allow'd, that what Nature gave the latter, was more than a Ballance for what Books had given the former; and the Judgment of a great Man upon this occasion was, I think, very just and proper. In a Conversation between Sir John Suckling, Sir William D'Avenant, Endymion Porter, Mr. Hales of Eaton, and Ben Johnson; Sir John Suckling, who was a profess'd Admirer of Shakespear, had undertaken his Defence against Ben Johnson with some warmth; Mr. Hales, who had sat still for some time, hearing Ben frequently reproaching him with the want of Learning, and Ignorance of the Antients, told him at last, That if Mr. Shakespear had not read the Antients, he had likewise not stollen any thing from 'em; (a Fault the other made no Confidence of) and that if he would produce any one Topick finely treated by any of them, he would undertake to shew something upon the same Subject at least as well written by Shakespear. Johnson did indeed take a large liberty, even to the transcribing and translating of whole Scenes together; and sometimes, with all Deference to so great a Name as his, not altogether for the advantage of the Authors of whom he borrow'd. And if Augustus and Virgil were really what he has made 'em in a Scene of his Poetaster, they are as odd an Emperor and a Poet as ever met. Shakespear, on the other Hand, was beholding to no body farther than the Foundation of the Tale, the Incidents were often his own, and the Writing intirely so. There is one Play of his, indeed, The Comedy of Errors, in a great measure taken from the Men[oe]chmi of Plautus. How that happen'd, I cannot easily Divine, since, as I hinted before, I do not take him to have been Master of Latin enough to read it in the Original, and I know of no Translation of Plautus so Old as his Time.

As I have not propos'd to my self to enter into a Large and Compleat Criticism upon Mr. Shakespear's Works, so I suppose it will neither be expected that I should take notice of the severe Remarks that have been formerly made upon him by Mr. Rhymer. I must confess, I can't very well see what could be the Reason of his animadverting with so much Sharpness, upon the Faults of a Man Excellent on most Occasions, and whom all the World ever was and will be inclin'd to have an Esteem and Veneration for. If it was to shew his own Knowledge in the Art of Poetry, besides that there is a Vanity in making that only his Design, I question if there be not many Imperfections as well in those Schemes and Precepts he has given for the Direction of others, as well as in that Sample of Tragedy which he has written to shew the Excellency of his own Genius. If he had a Pique against the Man, and wrote on purpose to ruin a Reputation so well establish'd, he has had the Mortification to fail altogether in his Attempt, and to see the World at least as fond of Shakespear as of his Critique. But I won't believe a Gentleman, and a good-natur'd Man, capable of the last Intention. Whatever may have been his Meaning, finding fault is certainly the easiest Task of Knowledge, and commonly those Men of good Judgment, who are likewise of good and gentle Dispositions, abandon this ungrateful Province to the Tyranny of Pedants. If one would enter into the Beauties of Shakespear, there is a much larger, as well as a more delightful Field; but as I won't prescribe to the Tastes of other People, so I will only take the liberty, with all due Submission to the Judgment of others, to observe some of those Things I have been pleas'd with in looking him over.

His Plays are properly to be distinguish'd only into Comedies and Tragedies. Those which are called Histories, and even some of his Comedies, are really Tragedies, with a run or mixture of Comedy amongst 'em. That way of Trage-Comedy was the common Mistake of that Age, and is indeed become so agreeable to the English Tast, that tho' the severer Critiques among us cannot bear it, yet the generality of our Audiences seem to be better pleas'd with it than with an exact Tragedy. The Merry Wives of Windsor, The Comedy of Errors, and The Taming of the Shrew, are all pure Comedy; the rest, however they are call'd, have something of both Kinds. 'Tis not very easie to determine which way of Writing he was most Excellent in. There is certainly a great deal of Entertainment in his Comical Humours; and tho' they did not then strike at all Ranks of People, as the Satyr of the present Age has taken the Liberty to do, yet there is a pleasing and a well-distinguish'd Variety in those Characters which he thought fit to meddle with. Falstaff is allow'd by every body to be a Master-piece; the Character is always well-sustain'd, tho' drawn out into the length of three Plays; and even the Account of his Death, given by his Old Landlady Mrs. Quickly, in the first Act of Henry V. tho' it be extremely Natural, is yet as diverting as any Part of his Life. If there be any Fault in the Draught he has made of this lewd old Fellow, it is, that tho' he has made him a Thief, Lying, Cowardly, Vain-glorious, and in short every way Vicious, yet he has given him so much Wit as to make him almost too agreeable; and I don't know whether some People have not, in remembrance of the Diversion he had formerly afforded 'em, been sorry to see his Friend Hal use him so scurvily, when he comes to the Crown in the End of the Second Part of Henry the Fourth. Amongst other Extravagances, in The Merry Wives of Windsor, he has made him a Dear-stealer, that he might at the same time remember his Warwickshire Prosecutor, under the Name of Justice Shallow; he has given him very near the same Coat of Arms which Dugdale, in his Antiquities of that County, describes for a Family there, and makes the Welsh Parson descant very pleasantly upon 'em. That whole Play is admirable; the Humours are various and well oppos'd; the main Design, which is to cure Ford his unreasonable Jealousie, is extremely well conducted. Falstaff's Billet-doux, and Master Slender's

are very good Expressions of Love in their Way. In Twelfth-Night there is something singularly Ridiculous and Pleasant in the fantastical Steward Malvolio. The Parasite and the Vain-glorious in Parolles, in All's Well that ends Well is as good as any thing of that Kind in Plautus or Terence. Petruchio, in The Taming of the Shrew, is an uncommon Piece of Humour. The Conversation of Benedick and Beatrice in Much ado about Nothing, and of Rosalind in As you like it, have much Wit and Sprightliness all along. His Clowns, without which Character there was hardly any Play writ in that Time, are all very entertaining: And, I believe, Thersites in Troilus and Cressida, and Apemantus in Timon, will be allow'd to be Master-Pieces of ill Nature, and satyrical Snarling. To these I might add, that incomparable Character of Shylock the Jew, in The Merchant of Venice; but tho' we have seen that Play Receiv'd and Acted as a Comedy, and the Part of the Jew perform'd by an Excellent Comedian, yet I cannot but think it was design'd Tragically by the Author. There appears in it such a deadly Spirit of Revenge, such a savage Fierceness and Fellness, and such a bloody designation of Cruelty and Mischief, as cannot agree either with the Stile or Characters of Comedy. The Play it self, take it all together, seems to me to be one of the most finish'd of any of Shakespear's. The Tale indeed, in that Part relating to the Caskets, and the extravagant and unusual kind of Bond given by Antonio, is a little too much remov'd from the Rules of Probability: But taking the Fact for granted, we must allow it to be very beautifully written. There is something in the Friendship of Antonio to Bassanio very Great, Generous and Tender. The whole fourth Act, supposing, as I said, the Fact to be probable, is extremely Fine. But there are two Passages that deserve a particular Notice. The first is, what Portia says in praise of Mercy, pag. 577; and the other on the Power of Musick, pag. 587. The Melancholy of Jacques, in As you like it, is as singular and odd as it is diverting. And if what Horace says

'Twill be a hard Task for any one to go beyond him in the Description of the several Degrees and Ages of Man's Life, tho' the Thought be old, and common enough.

p. 625.

His Images are indeed ev'ry where so lively, that the Thing he would represent stands full before you, and you possess ev'ry Part of it. I will venture to point out one more, which is, I think, as strong and as uncommon as any thing I ever saw; 'tis an Image of Patience. Speaking of a Maid in Love, he says,

What an Image is here given! and what a Task would it have been for the greatest Masters of Greece and Rome to have express'd the Passions design'd by this Sketch of Statuary? The Stile of his Comedy is, in general, Natural to the Characters, and easie in it self; and the Wit most commonly sprightly and pleasing, except in those places where he runs into Dogrel Rhymes, as in The Comedy of Errors, and a Passage or two in some other Plays. As for his Jingling sometimes, and playing upon Words, it was the common Vice of the Age he liv'd in: And if we find it in the Pulpit, made use of as an Ornament to the Sermons of some of the Gravest Divines of those Times; perhaps it may not be thought too light for the Stage.

But certainly the greatness of this Author's Genius do's no where so much appear, as where he gives his Imagination an entire Loose, and raises his Fancy to a flight above Mankind and the Limits of the visible World. Such are his Attempts in The Tempest, Midsummer-Night's Dream, Macbeth and Hamlet. Of these, The Tempest, however it comes to be plac'd the first by the former Publishers of his Works, can never have been the first written by him: It seems to me as perfect in its Kind, as almost any thing we have of his. One may observe, that the Unities are kept here with an Exactness uncommon to the Liberties of his Writing: Tho' that was what, I suppose, he valu'd himself least upon, since his Excellencies were all of another Kind. I am very sensible that he do's, in this Play, depart too much from that likeness to Truth which ought to be observ'd in these sort of Writings; yet he do's it so very finely, that one is easily drawn in to have more Faith for his sake, than Reason does well allow of. His Magick has something in it very Solemn and very Poetical: And that extravagant Character of Caliban is mighty well sustain'd, shews a wonderful Invention in the Author, who could strike out such a particular wild Image, and is certainly one of the finest and most uncommon Grotesques that was ever seen. The Observation, which I have been inform'd[A] three very great Men concurr'd in making upon this Part, was extremely just. That Shakespear had not only found out a new Character in his Caliban, but had also devis'd and adapted a new manner of Language for that Character. Among the particular Beauties of this Piece, I think one may be allow'd to point out the Tale of Prospero in the First Act; his Speech to Ferdinand in the Fourth, upon the breaking up the Masque of Juno and Ceres; and that in the Fifth, where he dissolves his Charms, and resolves to break his Magick Rod. This Play has been alter'd by Sir William D'Avenant and Mr. Dryden; and tho' I won't Arraign the Judgment of those two great Men, yet I think I may be allow'd to say, that there are some things left out by them, that might, and even ought to have been kept in. Mr. Dryden was an Admirer of our Author, and, indeed, he owed him a great deal, as those who have read them both may very easily observe. And, I think, in Justice to 'em both, I should not on this Occasion omit what Mr. Dryden has said of him.

Prologue to The Tempest, as it

is alter'd by Mr. Dryden.

It is the same Magick that raises the Fairies in Midsummer Night's Dream, the Witches in Macbeth, and the Ghost in Hamlet, with Thoughts and Language so proper to the Parts they sustain, and so peculiar to the Talent of this Writer. But of the two last of these Plays I shall have occasion to take notice, among the Tragedies of Mr. Shakespear. If one undertook to examine the greatest part of these by those Rules which are establish'd by Aristotle, and taken from the Model of the Grecian Stage, it would be no very hard Task to find a great many Faults: But as Shakespear liv'd under a kind of mere Light of Nature, and had never been made acquainted with the Regularity of those written Precepts, so it would be hard to judge him by a Law he knew nothing of. We are to consider him as a Man that liv'd in a State of almost universal License and Ignorance: There was no establish'd Judge, but every one took the liberty to Write according to the Dictates of his own Fancy. When one considers, that there is not one Play before him of a Reputation good enough to entitle it to an Appearance on the present Stage, it cannot but be a Matter of great Wonder that he should advance Dramatick Poetry so far as he did. The Fable is what is generally plac'd the first, among those that are reckon'd the constituent Parts of a Tragick or Heroick Poem; not, perhaps, as it is the most Difficult or Beautiful, but as it is the first properly to be thought of in the Contrivance and Course of the whole; and with the Fable ought to be consider'd, the fit Disposition, Order and Conduct of its several Parts. As it is not in this Province of the Drama that the Strength and Mastery of Shakespear lay, so I shall not undertake the tedious and ill-natur'd Trouble to point out the several Faults he was guilty of in it. His Tales were seldom invented, but rather taken either from true History, or Novels and Romances: And he commonly made use of 'em in that Order, with those Incidents, and that extent of Time in which he found 'em in the Authors from whence he borrow'd them. So The Winter's Tale, which is taken from an old Book, call'd, The Delectable History of Dorastus and Faunia, contains the space of sixteen or seventeen Years, and the Scene is sometimes laid in Bohemia, and sometimes in Sicily, according to the original Order of the Story. Almost all his Historical Plays comprehend a great length of Time, and very different and distinct Places: And in his Antony and Cleopatra, the Scene travels over the greatest Part of the Roman Empire. But in Recompence for his Carelessness in this Point, when he comes to another Part of the Drama, The Manners of his Characters, in Acting or Speaking what is proper for them, and fit to be shown by the Poet, he may be generally justify'd, and in very many places greatly commended. For those Plays which he has taken from the English or Roman History, let any Man compare 'em, and he will find the Character as exact in the Poet as the Historian. He seems indeed so far from proposing to himself any one Action for a Subject, that the Title very often tells you, 'tis The Life of King John, King Richard, &c. What can be more agreeable to the Idea our Historians give of Henry the Sixth, than the Picture Shakespear has drawn of him! His Manners are every where exactly the same with the Story; one finds him still describ'd with Simplicity, passive Sanctity, want of Courage, weakness of Mind, and easie Submission to the Governance of an imperious Wife, or prevailing Faction: Tho' at the same time the Poet do's Justice to his good Qualities, and moves the Pity of his Audience for him, by showing him Pious, Disinterested, a Contemner of the Things of this World, and wholly resign'd to the severest Dispensations of God's Providence. There is a short Scene in the Second Part of Henry VI. Vol. III. pag. 1504. which I cannot but think admirable in its Kind. Cardinal Beaufort, who had murder'd the Duke of Gloucester, is shewn in the last Agonies on his Death-Bed, with the good King praying over him. There is so much Terror in one, so much Tenderness and moving Piety in the other, as must touch any one who is capable either of Fear or Pity. In his Henry VIII. that Prince is drawn with that Greatness of Mind, and all those good Qualities which are attributed to him in any Account of his Reign. If his Faults are not shewn in an equal degree, and the Shades in this Picture do not bear a just Proportion to the Lights, it is not that the Artist wanted either Colours or Skill in the Disposition of 'em; but the truth, I believe, might be, that he forbore doing it out of regard to Queen Elizabeth, since it could have been no very great Respect to the Memory of his Mistress, to have expos'd some certain Parts of her Father's Life upon the Stage. He has dealt much more freely with the Minister of that Great King, and certainly nothing was ever more justly written, than the Character of Cardinal Wolsey. He has shewn him Tyrannical, Cruel, and Insolent in his Prosperity; and yet, by a wonderful Address, he makes his Fall and Ruin the Subject of general Compassion. The whole Man, with his Vices and Virtues, is finely and exactly describ'd in the second Scene of the fourth Act. The Distresses likewise of Queen Katherine, in this Play, are very movingly touch'd: and tho' the Art of the Poet has skreen'd King Henry from any gross Imputation of Injustice, yet one is inclin'd to wish, the Queen had met with a Fortune more worthy of her Birth and Virtue. Nor are the Manners, proper to the Persons represented, less justly observ'd, in those Characters taken from the Roman History; and of this, the Fierceness and Impatience of Coriolanus, his Courage and Disdain of the common People, the Virtue and Philosophical Temper of Brutus, and the irregular Greatness of Mind in M. Antony, are beautiful Proofs. For the two last especially, you find 'em exactly as they are describ'd by Plutarch, from whom certainly Shakespear copy'd 'em. He has indeed follow'd his Original pretty close, and taken in several little Incidents that might have been spar'd in a Play. But, as I hinted before, his Design seems most commonly rather to describe those great Men in the several Fortunes and Accidents of their Lives, than to take any single great Action, and form his Work simply upon that. However, there are some of his Pieces, where the Fable is founded upon one Action only. Such are more especially, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and Othello. The Design in Romeo and Juliet, is plainly the Punishment of their two Families, for the unreasonable Feuds and Animosities that had been so long kept up between 'em, and occasion'd the Effusion of so much Blood. In the management of this Story, he has shewn something wonderfully Tender and Passionate in the Love-part, and vary Pitiful in the Distress. Hamlet is founded on much the same Tale with the Electra of Sophocles. In each of 'em a young Prince is engag'd to Revenge the Death of his Father, their Mothers are equally Guilty, are both concern'd in the Murder of their Husbands, and are afterwards married to the Murderers. There is in the first Part of the Greek Trajedy, something very moving in the Grief of Electra; but as Mr. D'Acier has observ'd, there is something very unnatural and shocking in the Manners he has given that Princess and Orestes in the latter Part. Orestes embrues his Hands in the Blood of his own Mother; and that barbarous Action is perform'd, tho' not immediately upon the Stage, yet so near, that the Audience hear Clytemnestra crying out to Æghystus for Help, and to her Son for Mercy: While Electra, her Daughter, and a Princess, both of them Characters that ought to have appear'd with more Decency, stands upon the Stage and encourages her Brother in the Parricide. What Horror does this not raise! Clytemnestra was a wicked Woman, and had deserv'd to Die; nay, in the truth of the Story, she was kill'd by her own Son; but to represent an Action of this Kind on the Stage, is certainly an Offence against those Rules of Manners proper to the Persons that ought to be observ'd there. On the contrary, let us only look a little on the Conduct of Shakespear. Hamlet is represented with the same Piety towards his Father, and Resolution to Revenge his Death, as Orestes; he has the same Abhorrence for his Mother's Guilt, which, to provoke him the more, is heighten'd by Incest: But 'tis with wonderful Art and Justness of Judgment, that the Poet restrains him from doing Violence to his Mother. To prevent any thing of that Kind, he makes his Father's Ghost forbid that part of his Vengeance.

This is to distinguish rightly between Horror and Terror. The latter is a proper Passion of Tragedy, but the former ought always to be carefully avoided. And certainly no Dramatick Writer ever succeeded better in raising Terror in the Minds of an Audience than Shakespear has done. The whole Tragedy of Macbeth, but more especially the Scene where the King is murder'd, in the second Act, as well as this Play, is a noble Proof of that manly Spirit with which he writ; and both shew how powerful he was, in giving the strongest Motions to our Souls that they are capable of. I cannot leave Hamlet, without taking notice of the Advantage with which we have seen this Master-piece of Shakespear distinguish it self upon the Stage, by Mr. Betterton's fine Performance of that Part. A Man, who tho' he had no other good Qualities, as he has a great many, must have made his way into the Esteem of all Men of Letters, by this only Excellency. No Man is better acquainted with Shakespear's manner of Expression, and indeed he has study'd him so well, and is so much a Master of him, that whatever Part of his he performs he does it as if it had been written on purpose for him, and that the Author had exactly conceiv'd it as he plays it. I must own a particular Obligation to him, for the most considerable part of the Passages relating to his Life, which I have here transmitted to the Publick; his Veneration for the Memory of Shakespear having engag'd him to make a Journey into Warwickshire, on purpose to gather up what Remains he could of a Name for which he had so great a Value. Since I had at first resolv'd not to enter into any Critical Controversie, I won't pretend to enquire into the Justness of Mr. Rhymer's Remarks on Othello; he has certainly pointed out some Faults very judiciously; and indeed they are such as most People will agree, with him, to be Faults: But I wish he would likewise have observ'd some of the Beauties too; as I think it became an Exact and Equal Critique to do. It seems strange that he should allow nothing Good in the whole: If the Fable and Incidents are not to his Taste, yet the Thoughts are almost every where very Noble, and the Diction manly and proper. These last, indeed, are Parts of Shakespear's Praise, which it would be very hard to Dispute with him. His Sentiments and Images of Things are Great and Natural; and his Expression (tho' perhaps in some Instances a little Irregular) just, and rais'd in Proportion to his Subject and Occasion. It would be even endless to mention the particular Instances that might be given of this Kind: But his Book is in the Possession of the Publick, and 'twill be hard to dip into any Part of it, without finding what I have said of him made good.

The latter Part of his Life was spent, as all Men of good Sense will wish theirs may be, in Ease, Retirement, and the Conversation of his Friends. He had the good Fortune to gather an Estate equal to his Occasion, and, in that, to his Wish; and is said to have spent some Years before his Death at his native Stratford. His pleasurable Wit, and good Nature, engag'd him in the Acquaintance, and entitled him to the Friendship of the Gentlemen of the Neighbourhood. Amongst them, it is a Story almost still remember'd in that Country, that he had a particular Intimacy with Mr. Combe, an old Gentleman noted thereabouts for his Wealth and Usury: It happen'd, that in a pleasant Conversation amongst their common Friends, Mr. Combe told Shakespear in a laughing manner, that he fancy'd, he intended to write his Epitaph, if he happen'd to out-live him; and since he could not know what might be said of him when he was dead, he desir'd it might be done immediately: Upon which Shakespear gave him these four Verses.

But the Sharpness of the Satyr is said to have stung the Man so severely, that he never forgave it.

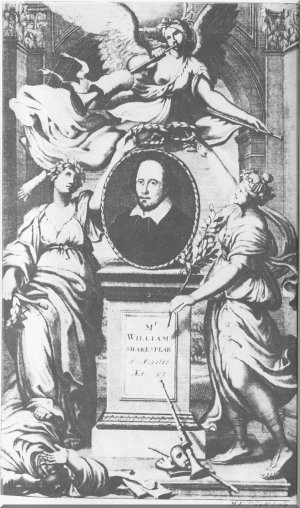

He Dy'd in the 53d Year of his Age, and was bury'd on the North side of the Chancel, in the Great Church at Stratford, where a Monument, as engrav'd in the Plate, is plac'd in the Wall. On his Grave-Stone underneath is,

He had three Daughters, of which two liv'd to be marry'd; Judith, the Elder, to one Mr. Thomas Quiney, by whom she had three Sons, who all dy'd without Children; and Susannah, who was his Favourite, to Dr. John Hall, a Physician of good Reputation in that Country. She left one Child only, a Daughter, who was marry'd first to Thomas Nash, Esq; and afterwards to Sir John Bernard of Abbington, but dy'd likewise without Issue.

This is what I could learn of any Note, either relating to himself or Family: The Character of the Man is best seen in his Writings. But since Ben Johnson has made a sort of an Essay towards it in his Discoveries, tho', as I have before hinted, he was not very Cordial in his Friendship, I will venture to give it in his Words.

"I remember the Players have often mention'd it as an Honour to Shakespear, that in Writing (whatsoever he penn'd) he never blotted out a Line. My Answer hath been, Would he had blotted a thousand, which they thought a malevolent Speech. I had not told Posterity this, but for their Ignorance, who chose that Circumstance to commend their Friend by, wherein he most faulted. And to justifie mine own Candor, (for I lov'd the Man, and do honour his Memory, on this side Idolatry, as much as any.) He was, indeed, Honest, and of an open and free Nature, had an Excellent Fancy, brave Notions, and gentle Expressions, wherein he flow'd with that Facility, that sometimes it was necessary he should be stopp'd: Sufflaminandus erat, as Augustus said of Haterius. His Wit was in his own Power, would the Rule of it had been so too. Many times he fell into those things could not escape Laughter; as when he said in the Person of Cæsar, one speaking to him,

"He reply'd:

and such like, which were ridiculous. But he redeem'd his Vices with his Virtues: There was ever more in him to be Prais'd than to be Pardon'd."

As for the Passage which he mentions out of Shakespear, there is somewhat like it Julius Cæsar, Vol. V. p. 2260. but without the Absurdity; nor did I ever meet with it in any Edition that I have seen, as quoted by Mr. Johnson. Besides his Plays in this Edition, there are two or three ascrib'd to him by Mr. Langbain, which I have never seen, and know nothing of. He writ likewise, Venus and Adonis, and Tarquin and Lucrece, in Stanza's, which have been printed in a late Collection of Poems. As to the Character given of him by Ben Johnson, there is a good deal true in it: But I believe it may be as well express'd by what Horace says of the first Romans, who wrote Tragedy upon the Greek Models, (or indeed translated 'em) in his Epistle to Augustus.

There is a Book of Poems, publish'd in 1640, under the Name of Mr. William Shakespear, but as I have but very lately seen it, without an Opportunity of making any Judgment upon it, I won't pretend to determine, whether it be his or no.

[A] Ld. Falkland, Ld. C.J. Vaughan, and Mr. Selden.

[B] Alluding to the Sea-Voyage of Fletcher.

ANNOUNCES ITS

Publications for the Third Year (1948-1949)

At least two items will be printed from each of the three following groups.

| Series IV: | Men, Manners, and Critics |

| Sir John Falstaff (pseud.), The Theatre (1720). | |

| Aaron Hill, Preface to The Creation, and Thomas Brereton, Preface to Esther. | |

| Ned Ward, Selected Tracts. | |

| Series V: | Drama |

| Edward Moore, The Gamester (1753). | |

| Nevil Payne, Fatal Jealousy (1673). | |

| Mrs. Centlivre, The Busie Body (1709). | |

| Charles Macklin, Man of the World (1781). | |

| Series VI: | Poetry and Language |

| John Oldmixon, Reflections on Dr. Swift's Letter to Harley (1712); and Arthur Mainwaring, The British Academy (1712). | |

| Pierre Nicole, De Epigrammate. | |

| Andre Dacier, Essay on Lyric Poetry. |

Issues will appear, as usual, in May, July, September, November, January, and March. In spite of rising costs, membership fees will be kept at the present annual rate of $2.50 in the United States and Canada, $2.75 in Great Britain and the continent. British and continental subscriptions should be sent to B.H. Blackwell, Broad Street, Oxford, England. American and Canadian subscriptions may be sent to any one of the General Editors.

TO THE AUGUSTAN REPRINT SOCIETY:

} the third year

I enclose the membership fee for } the second and third year

} the first, second, and third year

NAME

ADDRESS

NOTE: All income received by the Society is devoted to defraying cost of printing and mailing

MAKES AVAILABLE

Inexpensive Reprints of Rare Materials

FROM

ENGLISH LITERATURE OF THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES

Students, scholars, and bibliographers of literature, history, and philology will find the publications valuable. The Johnsonian News Letter has said of them: "Excellent facsimiles, and cheap in price, these represent the triumph of modern scientific reproduction. Be sure to become a subscriber; and take it upon yourself to see that your college library is on the mailing list."

The Augustan Reprint Society is a non-profit, scholarly organization, run without overhead expense. By careful management it is able to offer at least six publications each year at the unusually low membership fee of $2.50 per year in the United States and Canada, and $2.75 in Great Britain and the continent

Libraries as well as individuals are eligible for membership. Since the publications are issued without profit, however, no discount can be allowed to libraries, agents, or booksellers.

New members may still obtain a complete run of the first year's publications for $2.50, the annual membership fee.

During the first two years the publications are issued in three series: I. Essays on Wit; II. Essays on Poetry and Language; and III. Essays on the Stage.

| MAY, 1946: | Series I, No. 1—Richard Blackmore's Essay upon Wit (1716), and Addison's Freeholder No. 45 (1716). |

| JULY, 1946: | Series II, No. 1—Samuel Cobb's Of Poetry and Discourse on Criticism (1707). |

| SEPT., 1946: | Series III, No. 1—Anon., Letter to A.H. Esq.; concerning the Stage (1698), and Richard Willis' Occasional Paper No. IX (1698). |

| NOV., 1946: | Series I, No. 2—Anon., Essay on Wit (1748), together with Characters by Flecknoe, and Joseph Warton's Adventurer Nos. 127 and 133. |

| JAN., 1947: | Series II, No. 2—Samuel Wesley's Epistle to a Friend Concerning Poetry (1700) and Essay on Heroic Poetry (1693). |

| MARCH, 1947: | Series III, No. 2—Anon., Representation of the Impiety and Immorality of the Stage (1704) and anon., Some Thoughts Concerning the Stage (1704). |

PUBLICATIONS FOR THE SECOND YEAR (1947-1948)

| MAY, 1947: | Series I, No. 3—John Gay's The Present State of Wit; and a section on Wit from The English Theophrastus. With an Introduction by Donald Bond. |

| JULY, 1947: | Series II, No. 3—Rapin's De Carmine Pastorali, translated by Creech. With an Introduction by J.E. Congleton. |

| SEPT., 1947: | Series III, No. 3—T. Hanmer's (?) Some Remarks on the Tragedy of Hamlet. With an Introduction by Clarence D. Thorpe. |

| NOV., 1947: | Series I, No. 4—Corbyn Morris' Essay towards Fixing the True Standards of Wit, etc. With an Introduction by James L. Clifford. |

| JAN., 1948: | Series II, No. 4—Thomas Purney's Discourse on the Pastoral. With an Introduction by Earl Wasserman. |

| MARCH, 1948: | Series III, No. 4—Essays on the Stage, selected, with an Introduction by Joseph Wood Krutch. |

The list of publications is subject to modification in response to requests by members. From time to time Bibliographical Notes will be included in the issues. Each issue contains an Introduction by a scholar of special competence in the field represented.

The Augustan Reprints are available only to members. They will never be offered at "remainder" prices.

GENERAL EDITORS

Richard C. Boys, University of Michigan

Edward Niles Hooker, University of California, Los Angeles

H.t. Swedenberg, Jr., University of California, Los Angeles

ADVISORY EDITORS

Emmett L. Avery, State College of Washington

Louis I. Bredvold, University of Michigan

Benjamin Boyce, University of Nebraska

Cleanth Brooks, Louisiana State University

James L. Clifford, Columbia University

Arthur Friedman, University of Chicago

Samuel H. Monk, University of Minnesota

James Sutherland, Queen Mary College, London

Address communications to any of the General Editors. Applications for membership, together with membership fee, should be sent to

The Augustan Reprint Society

310 Royce Hall, University Of California

Los Angeles 24, California

or

Care of Professor Richard C. Boys

Angell Hall, University Of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan

Please enroll me as a member of the Augustan Reprint Society.

I enclose {$2.50 } as the membership fee for } the second year.

{ 5.00 }

} the first and second year.

NAME

Address

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Some Account of the Life of Mr.

William Shakespear (1709), by Nicholas Rowe

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MR. WILLIAM SHAKESPEAR ***

***** This file should be named 16275-h.htm or 16275-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/1/6/2/7/16275/

Produced by David Starner, Louise Pryor and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.net),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he