The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Militants, by Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Militants

Stories of Some Parsons, Soldiers, and Other Fighters in the World

Author: Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews

Release Date: March 29, 2005 [EBook #15496]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MILITANTS ***

Produced by Kentuckiana Digital Library, David Garcia, Martin Pettit

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

"The sword of the Lord and of Gideon."

PUBLISHED BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

| The Militants. Illustrated | $1.50 |

| Bob and the Guides. Illustrated | $1.50 |

| The Perfect Tribute. With Frontispiece | $0.50 |

| Vive L'Empereur. Illustrated | $1.00 |

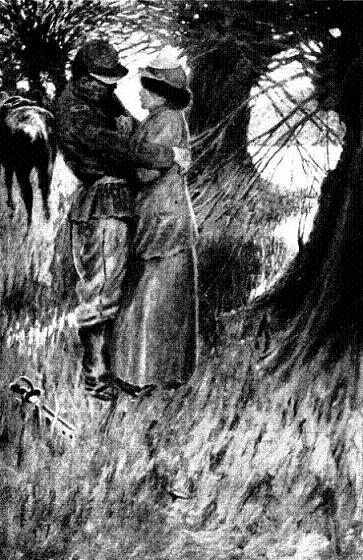

"I took her in my arms and held her."

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1907

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF A MAN WHO WAS WITH HIS WHOLE HEART A PRIEST AND WITH HIS WHOLE STRENGTH A SOLDIER OF THE CHURCH MILITANT.

JACOB SHAW SHIPMAN

The Bishop was walking across the fields to afternoon service. It was a hot July day, and he walked slowly—for there was plenty of time—with his eyes fixed on the far-off, shimmering sea. That minstrel of heat, the locust, hidden somewhere in the shade of burning herbage, pulled a long, clear, vibrating bow across his violin, and the sound fell lazily on the still air—the only sound on earth except a soft crackle under the Bishop's feet. Suddenly the erect, iron-gray head plunged madly forward, and then, with a frantic effort and a parabola or two, recovered itself, while from the tall grass by the side of the path gurgled up a high, soft, ecstatic squeal. The Bishop, his face flushed with the stumble and the heat and a touch of indignation besides, straightened himself with dignity and felt for his hat, while his eyes followed a wriggling cord that lay on the ground, up to a small brown fist. A burnished head, gleaming in the sunshine like the gilded ball on a church steeple, rose suddenly out of the waves of dry grass, and a pink-ginghamed figure, radiant with joy and good-will, confronted him. The Bishop's temper, roughly waked up by the unwilling and unepiscopal war-dance just executed, fell back into its chains.

"Did you tie that string across the path?"

"Yes," The shining head nodded. "Too bad you didn't fell 'way down. I'm sorry. But you kicked awf'ly."

"Oh! I did, did I?" asked the Bishop. "You're an unrepentant young sinner. Suppose I'd broken my leg?"

The head nodded again. "Oh, we'd have patzed you up," she said cheerfully. "Don't worry. Trust in God."

The Bishop jumped. "My child," he said, "who says that to you?"

"Aunt Basha." The innocent eyes faced him without a sign of embarrassment. "Aunt Basha's my old black mammy. Do you know her? All her name's longer'n that. I can say it." Then with careful, slow enunciation, "Bathsheba Salina Mosina Angelica Preston."

"Is that your little bit of name too?" the Bishop asked, "Are you a Preston?"

"Why, of course." The child opened her gray eyes wide. "Don't you know my name? I'm Eleanor. Eleanor Gray Preston."

For a moment again the locust had it all to himself. High and insistent, his steady note sounded across the hot, still world. The Bishop looked down at the gray eyes gazing upward wonderingly, and through a mist of years other eyes smiled at him. Eleanor Gray—the world is small, the life of it persistent; generations repeat themselves, and each is young but once. He put his hand under the child's chin and turned up the baby face.

"Ah!" said he—if that may stand for the sound that stood for the Bishop's reverie. "Ah! Whom were you named for, Eleanor Gray?"

"For my own muvver." Eleanor wriggled her chin from the big hand and looked at him with dignity. She did not like to be touched by strangers. Again the voices stopped and the locust sang two notes and stopped also, as if suddenly awed.

"Your mother," repeated the Bishop, "your mother! I hope you are worthy of the name."

"Yes, I am," said Eleanor heartily. "Bug's on your shoulder, Bishop! For de Lawd's sake!" she squealed excitedly, in delicious high notes that a prima donna might envy; then caught the fat grasshopper from the black clerical coat, and stood holding it, lips compressed and the joy of adventure dancing in her eyes. The Bishop took out his watch and looked at it, as Eleanor, her soul on the grasshopper, opened her fist and flung its squirming contents, with delicious horror, yards away. Half an hour yet to service and only five minutes' walk to the little church of Saint Peter's-by-the-Sea.

"Will you sit down and talk to me, Eleanor Gray?" he asked, gravely.

"Oh, yes, if there's time," assented Eleanor, "but you mustn't be late to church, Bishop. That's naughty."

"I think there's time. How do you know who I am, Eleanor?"

"Dick told me."

The Bishop had walked away from the throbbing sunshine into the green-black shadows of a tree, and seated himself with a boyish lightness in piquant contrast with his gray-haired dignity—a lightness that meant athletic years. Eleanor bent down the branch of a great bush that faced him and sat on it as if a bird had poised there. She smiled as their eyes met, and began to hum an air softly. The startled Bishop slowly made out a likeness to the words of the old hymn that begins

Sweetly and reverently she sang it, over and over, with a difference.

sang Eleanor.

The Bishop exploded into a great laugh that drowned the music.

"Aunt Basha taught you that, too, didn't she?" he asked, and off he went into another deep-toned peal.

"I thought you'd like that, 'cause it's a hymn and you're a Bishop," said Eleanor, approvingly. Her effort was evidently meeting with appreciation. "You can talk to me now, I'm here." She settled herself like a Brownie, elbows on knees, her chin in the hollows of small, lean hands, and gazed at him unflinchingly.

"Thank you," said the Bishop, sobering at once, but laughter still in his eyes. "Will you be kind enough to tell me then, Eleanor, who is Dick?"

Eleanor looked astonished, "You don't know anybody much, do you?" and there was gentle pity in her voice. "Why, Dick, he's—why, he's—why, you see, he's my friend. I don't know his uvver names, but Mr. Fielding, he's Dick's favver."

"Oh!" said the Bishop with comprehension. "Dick Fielding. Then Dick is my friend, too. And people that are friends to the same people should be friends to each other—that's geometry, Eleanor, though it's possibly not life."

"Huh?" Eleanor stared, puzzled.

"Will you be friends with me, Eleanor Gray? I knew your mother a long time ago, when she was Eleanor Gray." Eleanor yawned frankly. That might be true, but it did not appear to her remarkable or interesting. The deep voice went on, with a moment's interval. "Where is your mother? Is she here?"

Eleanor laughed. "Oh, no," she said. "Don't you know? What a funny man you are—you know such a few things. My muvver's up in heaven. She went when I was a baby, long, long ago. I reckon she must have flewed," she added, reflectively, raising clear eyes to the pale, heat-worn sky that gleamed through the branches.

The Bishop's big hands went up to his face suddenly, and the strong fingers clasped tensely above his forehead. Between his wrists one could see that his mouth was set in a hard line. "Dead!" he said. "And I never knew it."

Eleanor dug a small russet heel unconcernedly into the ground. "Naughty, naughty, naughty little grasshopper," she began to chant, addressing an unconscious insect near the heel. "Don't you go and crawl up on the Bishop. No, just don't you. 'Cause if you do, oh, naughty grasshopper, I'll scrunch you!" with a vicious snap on the "scrunch."

The Bishop lowered his hands and looked at her. "I'm not being very interesting, Eleanor, am I?"

"Not very," Eleanor admitted. "Couldn't you be some more int'rstin'?"

"I'll try," said the Bishop. "But be careful not to hurt the poor grasshopper. Because, you know, some people say that if he is a good grasshopper for a long time, then when he dies his little soul will go into a better body—perhaps a butterfly's body next time."

Eleanor caught the thought instantly. "And if he's a good butterfly, then what'll he be? A hummin'-bird? Let's kill him quick, and see him turn into a butterfly."

"Oh, no, Eleanor, you can't force the situation. He has to live out his little grasshopper life the best that he can, before he's good enough to be a butterfly. If you kill him now you might send him backward. He might turn into what he was before—a poor little blind worm perhaps."

"Oh, my Lawd!" said Eleanor.

The Bishop was still a moment, and then repeated, quietly:

"Oughtn't to talk to yourself," Eleanor shook her head disapprovingly. "'Tisn't so very polite. Is that true about the grasshopper, Bishop, or is it a whopper?"

The Bishop thought for a moment. "I don't know, Eleanor," he answered, gently.

"You don't know so very much, do you?" inquired Eleanor, not as despising but as wondering, sympathizing with ignorance.

"Very little," the Bishop agreed. "And I've tried to learn, all my life"—his gaze wandered off reflectively.

"Too bad," said Eleanor. "Maybe you'll learn some time."

"Maybe," said the Bishop and smiled, and suddenly she sprang to her feet, and shook her finger at him.

"I'm afraid," she said, "I'm very much afraid you're a naughty boy."

The Bishop looked up at the small, motherly face, bewildered. "Wh—why?" he stammered.

"Do you know what you're bein'? You're bein' late to church!"

The Bishop sprang up too, at that, and looked at his watch quickly. "Not late yet, but I'll walk along. Where are you going, waif? Aren't you in charge of anybody?"

"Huh?" inquired Eleanor, her head cocked sideways.

"Whom did you come out with?"

"Madge and Dick, but they're off there," nodding toward the wood behind them. "Madge is cryin'. She wouldn't let me pound Dick for makin' her, so I went away."

"Who is Madge?"

Eleanor, drifting beside him through the sunshine like a rose-leaf on the wind, stopped short. "Why, Bishop, don't you know even Madge? Funny Bishop! Madge is my sister—she's grown up. Dick made her cry, but I think he wasn't much naughty, 'cause she would not let me pound him. She put her arms right around him."

"Oh!" said the Bishop, and there was silence for a moment. "You mustn't tell me any more about Madge and Dick, I think, Eleanor."

"All right, my lamb!" Eleanor assented, cheerfully, and conversation flagged.

"How old are you, Eleanor Gray?"

"Six, praise de Lawd!"

The Bishop considered deeply for a moment, then his face cleared.

"'Their angels do always behold the face of my Father,'" and he smiled. "I say it too, praise the Lord that she is six."

"Madge is lots more'n that," the soft little voice, with its gay, courageous inflection, went on. "She's twenty. Isn't that old? You aren't much different of that, are you?" and the heavy, cropped, straight gold mass of her hair swung sideways as she turned her face up to scrutinize the tall Bishop.

He smiled down at her. "Only thirty years different. I'm fifty, Eleanor."

"Oh!" said Eleanor, trying to grasp the problem. Then with a sigh she gave it up, and threw herself on the strength of maturity. "Is fifty older'n twenty?" she asked.

More than once as they went side by side on the narrow foot-path across the field the Bishop put out his hand to hold the little brown one near it, but each time the child floated from his touch, and he smiled at the unconscious dignity, the womanly reserve of the frank and friendly little lady. "Thus far and no farther," he thought, with the quick perception of character that was part of his power. But the Bishop was as unconscious as the child of his own charm, of the magnetism in him that drew hearts his way. Only once had it ever failed, and that was the only time he had cared. But this time it was working fast as they walked and talked together quietly, and when they reached the open door that led from the fields into the little robing-room of Saint Peter's, Eleanor had met her Waterloo. Being six, it was easy to say so, and she did it with directness, yet without at all losing the dignity that was breeding, that had come to her from generations, and that she knew of as little as she knew the names of her bones. Three steps led to the robing-room, and Eleanor flew to the top and turned, the childish figure in its worn pink cotton dress facing the tall powerful one in sober black broadcloth.

"I love you," she said. "I'll kiss you," and the long, strong little arms were around his neck, and it seemed to the Bishop as if a kiss that had never been given came to him now from the lips of the child of the woman he had loved. As he put her down gently, from the belfry above tolled suddenly a sweet, rolling note for service.

When the Bishop came out from church the "peace that passeth understanding" was over him. The beautiful old words that to churchmen are dear as their mothers' faces, haunting as the voices that make home, held him yet in the last echo of their music. Peace seemed, too, to lie across the world, worn with the day's heat, where the shadows were stretching in lengthening, cooling lines. And there at the vestry step, where Eleanor had stood an hour before, was Dick Fielding, waiting for him, with as unhappy a face as an eldest scion, the heir to millions, well loved, and well brought up, and wonderfully unspoiled, ever carried about a country-side. The Bishop was staying at the Fieldings'. He nodded and swung past Dick, with a look from the tail of his eye that said: "Come along." Dick came, and silently the two turned into the path of the fields. The scowl on Dick's dark face deepened as they walked, and that was all there was by way of conversation for some time. Finally:

"You don't know about it, do you, Bishop?" he asked.

"A very little, my boy," the Bishop answered.

Dick was on the defensive in a moment. "My father told you—you agree with him?"

"Your father has told me nothing. I only came last night, remember. I know that you made Madge cry, and that Eleanor wasn't allowed to punish you."

The boyish face cleared a little, and he laughed. "That little rat! Has she been talking? It's all right if it's only to you, but Madge will have to cork her up." Then anxiety and unhappiness seized Dick's buoyant soul again. "Bishop, let me talk to you, will you please? I'm knocked up about this, for there's never been trouble between my father and me before, and I can't give in. I know I'm right—I'd be a cad to give in, and I wouldn't if I could. If you would only see your way to talking to the governor, Bishop! He'll listen to you when he'd throw any other chap out of the house."

"Tell me the whole story if you can, Dick, I don't understand, you see."

"I suppose it will sound rather commonplace to you," said Dick, humbly, "but it means everything to me. I—I'm engaged to Madge Preston. I've known her for a year, and been engaged half of it, and I ought to know my own mind by now. But father has simply set his forefeet and won't hear of it. Won't even let me talk to him about it."

Dick's hands went into his pockets and his head drooped, and his big figure lagged pathetically. The Bishop put his hand on the young man's shoulder, and left it there as they walked slowly on, but he said nothing.

"It's her father, you know," Dick went on. "Such rot, to hold a girl responsible for her ancestors! Isn't it rot, now? Father says they're a bad stock, dissipated and arrogant and spendthrift and shiftless and weak—oh, and a lot more! He's not stingy with his adjectives, bless you! Picture to yourself Madge being dissipated and arrogant and—have you seen Madge?" he interrupted himself.

The Bishop shook his head. "Eleanor made an attempt on my life with a string across the path, to-day. We were friends over that."

"She's a winning little rat," said Dick, smiling absent-mindedly, "but nothing to Madge. You'll understand when you see Madge how I couldn't give her up. And it isn't so much that—my feeling for her—though that's enough in all conscience, but picture to yourself, if you please, a man going to a girl and saying: 'I'm obliged to give you up, because my father threatens to disinherit me and kick me out of the business. He objects because your father's a poor lot.' That's a nice line of conduct to map out for your only son. Yet that's practically what my father wishes me to do. But he's brought me up a gentleman, by George," said Dick straightening himself, "and it's too late to ask me to be a beastly cad. Besides that," and voice and figure drooped to despondency again, "I just can't give her up."

The Bishop's keen eyes were on the troubled face, and in their depths lurked a kindly shade of amusement. He could see stubborn old Dick Fielding in stubborn young Dick Fielding so plainly. Dick the elder had been his friend for forty years. But he said nothing. It was better to let the boy talk himself out a bit. In a moment Dick began again.

"Can't see why the governor's so keen against Colonel Preston, anyway. He's lost his money and made a mess of his life, and I rather fancy he drinks too much. But he's the sort of man you can't help being proud of—bad clothes and vices and all—handsome and charming and thorough-bred—and father must know it. His children love him—he can't be such a brute as the governor says. Anyway, I don't want to marry the Colonel—what's the use of rowing about the Colonel?" inquired Dick, desperately.

The Bishop asked a question now: "How many children are there?"

"Only Madge and Eleanor. They're here with their cousins, the Vails, summers. Two or three died between those two, I believe. Lucky, perhaps, for the family has been awfully hard up. Lived on in their big old place, in Maryland, with no money at all. I've an idea Madge's mother wasn't so sorry to die—had a hard life of it with the fascinating Colonel." The Bishop's hand dropped from the boy's shoulder, and shut tightly. "But that has nothing to do with my marrying Madge," Dick went on.

"No," said the Bishop, shortly.

"And you see," said Dick, slipping to another tangent, "it's not the money I'm keenest about, though of course I want that too, but it's father. You believe I think more of my father than of his money, don't you? We've been good friends all my life, and he's such a crackerjack old fellow. I'd hate to get along without him." Dick sighed, from his boots up—almost six feet. "Couldn't you give him a dressing down, Bishop? Make him see reason?" He looked anxiously up the three inches that the Bishop towered above him.

At ten o'clock the next morning Richard Fielding, owner of the great Fielding Foundries, strolled out on his wide piazza, which, luxurious in deep wicker chairs and Japanese rugs and light, cool furniture, looked under scarlet and white awnings, across long boxes of geraniums and vines, out to the sparkling Atlantic. The Bishop, a friendly light coming into his thoughtful eyes, took his cigar from his lips and glanced up at his friend. Mr. Fielding kicked a hassock aside, moved a table between them, and settled himself in another chair, and with the scratch of a match, but without a word spoken, they entered into the companionship which had been a life-long joy to both.

"Father and the Bishop are having a song and dance without words," Dick was pleased sometimes to say, and felt that he hit it off. The breeze carried the scent of the tobacco in intermittent waves of fragrance, and on the air floated delicately that subtle message of peace, prosperity, and leisure which is part of the mission of a good cigar. The pleasantness of the wide, cool piazza, with its flowers and vines and gay awnings; the charm of the summer morning, not yet dulled by wear and tear of the day; the steady, deliberate dash of the waves on the beach below; the play and shimmer of the big, quiet water, stretching out to the edge of the world; all this filled their minds, rested their souls. There was no need for words. The Bishop sighed comfortably as he pushed his great shoulders back against the cool wicker of the chair and swung one long leg across the other. Fielding, chin up and lips rounded to let out a cloud of smoke, rested his hand, cigar between the fingers, on the table, and gazed at him satisfied. This was the man, after Dick, dearest to him in the world. Into which peaceful Eden stole at this point the serpent, and, as is usual, in the shape of woman. Little Eleanor, long-legged, slim, fresh as a flower in her crisp, faded pink dress, came around the corner. In one hot hand she carried, by their heads, a bunch of lilac and pink and white sweet peas. It cost her no trouble at all, and about half a minute of time, to charge the atmosphere, so full of sweet peace and rest, with a saturated solution of bitterness and disquiet. Her presence alone was a bombshell, and with a sentence or two in her clear, innocent voice, the fell deed was done. Fielding stopped smoking, his cigar in mid-air, and stared with a scowl at the child; but Eleanor, delighted to have found the Bishop, saw only him. A shower of crushed blossoms fell over his knees.

"I ran away from Aunt Basha. I brought you a posy for 'Good-mornin','" she said. The Bishop, collecting the plunder, expressed gratitude. "Dick picked a whole lot for Madge, and then they went walkin' and forgot 'em. Isn't Dick funny?" she went on.

Mr. Fielding looked as if Dick's drollness did not appeal to him, but the Bishop laughed, and put his arm around her.

"Will you give me a kiss, too, for 'Good-morning,'" he said; and then, "That's better than the flowers. You had better run back to Aunt Basha now, Eleanor—she'll be frightened."

Eleanor looked disappointed, "I wanted to ask you 'bout what dead chickens gets to be, if they're good. Pups? Do you reckon it's pups?"

The theory of transmigration of souls had taken strong hold. Mr. Fielding lost his scowl in a look of bewilderment, and the Bishop frankly shouted out a big laugh.

"Listen, Eleanor. This afternoon I'll come for you to walk, and we'll talk that all over. Go home now, my lamb." And Eleanor, like a pale-pink over-sized butterfly, went.

"Do you know that child, Jim?" Mr. Fielding asked, grimly.

"Yes," answered the Bishop, with a serene pull at his cigar.

"Do you know she's the child of that good-for-nothing Fairfax Preston, who married Eleanor Gray against her people's will and took her South to—to—starve, practically?"

The Bishop drew a long breath, and then he turned and looked at his old friend with a clear, wide gaze. "She's Eleanor Gray's child, too, Dick," he said.

Mr. Fielding was silent a moment. "Has the boy talked to you?" he asked. The Bishop nodded. "It's the worst trouble I've ever had. It would kill me to see him marry that man's daughter. I can't and won't resign myself to it. Why should I? Why should Dick choose, out of all the world, the one girl in it who would be insufferable to me. I can't give in about this. Much as Dick is to me I'll let him go sooner. I hope you'll see I'm right, Jim, but right or wrong, I've made up my mind."

The Bishop stretched a large, bony hand across the little table that stood between them. Fielding's fell on it. Both men smoked silently for a minute.

"Have you anything against the girl, Dick?" asked the Bishop, presently.

"That she's her father's daughter—it's enough. The bad blood of generations is in her. I don't like the South—I don't like Southerners. And I detest beyond words Fairfax Preston. But the girl is certainly beautiful, and they say she is a good girl, too," he acknowledged, gloomily.

"Then I think you're wrong," said the Bishop.

"You don't understand, Jim," Fielding took it up passionately. "That man has been the bête noir of my life. He has gotten in my way half-a-dozen times deliberately, in business affairs, little as he amounts to himself. Only two years ago—but that isn't the point after all." He stopped gloomily. "You'll wonder at me, but it's an older feud than that. I've never told anyone, but I want you to understand, Jim, how impossible this affair is." He bit off the end of a fresh cigar, lighted it and then threw it across the geraniums into the grass. "I wanted to marry her mother," he said, brusquely. "That man got her. Of course, I could have forgiven that, but it was the way he did it. He lied to her—he threw it in my teeth that I had failed. Can't you see how I shall never forgive him—never, while I live!" The intensity of a life-long, silent hatred trembled in his voice.

"It's the very thing it's your business to do, Dick," said the Bishop, quietly. "'Love your enemies, bless them that curse you'—what do you think that means? It's your very case. It may be the hardest thing in the world, but it's the simplest, most obvious." He drew a long puff at his cigar, and looked over the flowers to the ocean.

"Simple! Obvious!" Fielding's voice was full of bitterness. "That's the way with you churchmen! You live outside passions and temptations, and then preach against them, with no faintest notion of their force. It sounds easy, doesn't it? Simple and obvious, as you say. You never loved Eleanor Gray, Jim; you never had to give her up to a man you knew beneath her; you never had to shut murder out of your heart when you heard that he'd given her a hard life and a glad death. Eleanor Gray! Do you remember how lovely she was, how high-spirited and full of the joy of life?" The Bishop's great figure was still as if the breath in it had stopped, but Fielding, carried on the flood of his own rushing feeling, did not notice. "Do you remember, Jim?" he repeated.

"I remember," the Bishop said, and his voice sounded very quiet.

"Jove! How calm you are!" exploded the other.

"You're a churchman; you live behind a wall, you hear voices through it, but you can't be in the fight—it's easy for you."

"Life isn't easy for anyone, Dick," said the Bishop, slowly. "You know that. I'm fighting the current as well as you. You are a churchman as well as I. If it's my métier to preach against human passion, it's yours to resist it. You're letting this man you hate mould your character; you're letting him burn the kindness out of your soul. He's making you bitter and hard and unjust—and you're letting him. I thought you had more will—more poise. It isn't your affair what he is, even what he does, Dick—it's your affair to keep your own judgment unwarped, your own heart gentle, your own soul untainted by the poison of hatred. We are both churchmen, as you put it—loyalty is for us both. You live your sermon—I say mine. I have said it. Now live yours. Put this wormwood away from you. Forgive Preston, as you need forgiveness at higher hands. Don't break the girl's heart, and spoil your boy's life—it may spoil it—the leaven of bitterness works long. You're at a parting of the ways—take the right turn. Do good and not evil with your strength; all the rest is nothing. After all the years there is just one thing that counts, and that our mothers told us when we were little chaps together—be good, Dick."

The magnetic voice, that had swayed thousands, the indescribable trick of inflection that caught the heart-strings, the pure, high personality that shone through look and tone, had never, in all his brilliant career, been more full of power than for this audience of one. Fielding got up, trembling, and stood before him.

"Jim," he said, "whatever else is so, you are that—you are a good man. The trouble is you want me to be as good as you are; and I can't. If you had had temptations like mine, trials like mine, I might try to follow you—I would try. But you haven't—you're an impossible model for me. You want me to be an angel of light, and I'm only—a man." He turned and went into the house.

The oldest inhabitant had not seen a devotion like the Bishop's and Eleanor's. There was in it no condescension on one side, no strain on the other. The soul that through fulness of life and sorrow and happiness and effort had reached at last a child's peace met as its like the little child's soul, that had known neither life nor sorrow nor conscious happiness, and was without effort as a lily of the field. It may be that the wisdom of babyhood and the wisdom of age will look very alike to us when we have the wisdom of eternity. And as all the colors of the spectrum make sunlight, so all his splendid powers that patient years had made perfect shone through the Bishop's character in the white light of simplicity. No one knew what they talked about, the child and the man, on the long walks that they took together almost every day, except from Eleanor's conversation after. Transmigration, done into the vernacular, and applied with startling directness, was evidently a fascinating subject from the first. She brought back as well a vivid and epigrammatic version of the nebular hypothesis.

"Did you hear 'bout what the world did?" she demanded, casually, at the lunch-table. "We were all hot, nasty steam, just like a tea-kettle, and we cooled off into water, sailin' around so much, and then we got crusts on us, bless de Lawd, and then, sir, we kept on gettin' solid, and circus animals grewed all over us, and then they died, and thank God for that, and Adam and Evenin' camed, and Madge can't I have some more gingerbread? I'd just as soon be a little sick if you'll let me have it."

The "fairyland of science and the long results of time," passing from the Bishop's hands into the child's, were turned into such graphic tales, for Eleanor, with all her airy charm, struck straight from the shoulder. Never was there a sense of superiority on the Bishop's side, or of being lectured on Eleanor's.

"Why do you like to walk with the Bishop?" Mrs. Vail asked, curiously.

"Because he hasn't any morals," said the little girl, fresh from a Sunday-school lesson.

Saturday night Mr. Fielding stayed late in the city, and Dick was with his lady-love at the Vails; so the Bishop, after dining alone, went down on the wide beach below the house and walked, as he smoked his cigar. Through the week he had been restless under the constant prick of a duty undone, which he could not make up his mind to do. Over and over he heard his friend's agitated voice. "If you had had temptations like mine, trials like mine, I would try to follow you," it said. He knew that the man would be good as his word. He could perhaps win Dick's happiness for him if he would pick up the gauntlet of that speech. If he could bring himself to tell Fielding the whole story that he had shut so long ago into silence—that he, too, had cared for Eleanor Gray, and had given her up in a harder way than the other, for the Bishop had made it possible that the Southerner should marry her. But it was like tearing his soul to do it. No one but his mother, who was dead, had known this one secret of a life like crystal. The Bishop's reticence was the intense sort, that often goes with a frank exterior, and he had never cared for another woman. Some men's hearts are open pleasure-grounds, where all the world may come and go, and the earth is dusty with many feet; and some are like theatres, shut perhaps to the world in general, but which a passport of beauty or charm may always open; and with many, of finer clay, there are but two or three ways into a guarded temple, and only the touchstone of quality may let pass the lightest foot upon the carefully tended sod. But now and then a heart is Holy of Holies. Long ago the Bishop, lifting a young face from the books that absorbed him, had seen a girl's figure filling the narrow doorway, and dazzled by the radiance of it, had placed that image on the lonely altar, where the flame waited, before unconsecrated. Then the girl had gone, and he had quietly shut the door and lived his life outside. But the sealed place was there, and the fire burned before the old picture. Why should he, for Dick Fielding, for any one, let the light of day upon that stillness? The one thing in life that was his own, and all these years he had kept it sacred—why should he? Fiercely, with the old animal jealousy of ownership, he guarded for himself that memory—what was there on earth that could make him share it? And in answer there rose before him the vision of Madge Preston, with a haunting air of her mother about her; of young Dick Fielding, almost his own child from babyhood, his honest soul torn between two duties; of old Dick Fielding, loyal and kind and obstinate, his stubborn feet, the feet that had walked near his for forty years, needing only a touch to turn them into the right path.

Back and forth the thoughts buffeted each other, and the Bishop sighed, and threw away his cigar, and then stopped and stared out at the darkening, great ocean. The steady rush and pause and low wash of retreat did not calm him to-night.

"I'd like to turn it off for five minutes. It's so eternally right," he said aloud and began to walk restlessly again.

Behind him came light steps, but he did not hear them on the soft sand, in the noise of a breaking wave. A small, firm hand slipped into his was the first that he knew of another presence, and he did not need to look down at the bright head to know it was Eleanor, and the touch thrilled him in his loneliness. Neither spoke, but swung on across the sand, side by side, the child springing easily to keep pace with his great step. Beside the gift of English, Eleanor had its comrade gift of excellent silence. Those who are born to know rightly the charm and the power and the value of words, know as well the value of the rests in the music. Little Eleanor, her nervous fingers clutched around the Bishop's big thumb, was pouring strength and comfort into him, and such an instinct kept her quiet.

So they walked for a long half-hour, the Bishop fighting out his battle, sometimes stopping, sometimes talking aloud to himself, but Eleanor, through it all, not speaking. Once or twice he felt her face laid against his hand, and her hair that brushed his wrist, and the savage selfishness of reserve slowly dissolved in the warmth of that light touch and the steady current of gentleness it diffused through him. Clearly and more clearly he saw his way and, as always happens, as he came near to the mountain, the mountain grew lower. "Over the Alps lies Italy." Why should he count the height when the Italy of Dick's happiness and Fielding's duty done lay beyond? The clean-handed, light-hearted disregard of self that had been his habit of mind always came flooding back like sunshine as he felt his decision made. After all, doing a duty lies almost entirely in deciding to do it. He stooped and picked Eleanor up in his arms.

"Isn't the baby sleepy? We've settled it together—it's all right now, Eleanor. I'll carry you back to Aunt Basha."

"Is it all right now?" asked Eleanor, drowsily. "No, I'll walk," kicking herself downward. "But you come wiv me." And the Bishop escorted his lady-love to her castle, where the warden, Aunt Basha, was for this half hour making night vocal with lamentations for the runaway.

"Po' lil lamb!" said Aunt Basha, with an undisguised scowl at the Bishop. "Seems like some folks dunno nuff to know a baby's bedtime. Seems like de Lawd's anointed wuz in po' business, ti'in' out chillens!"

"I'm sorry, Aunt Basha," said the Bishop, humbly. "I'll bring her back earlier again. I forgot all about the time."

"Huh!" was all the response that Aunt Basha vouchsafed, and the Bishop, feeling himself hopelessly in the wrong, withdrew in discreet silence.

Luncheon was over the next day and the two men were quietly smoking together in the hot, drowsy quiet of the July mid-afternoon before the Bishop found a chance to speak to Fielding alone. There was an hour and a half before service, and this was the time to say his say, and he gathered himself for it, when suddenly the tongue of the ready speaker, the savoir faire of the finished man of the world, the mastery of situations which had always come as easily as his breath, all failed him at once.

"Dick," he stammered, "there is something I want to tell you," and he turned on his friend a face which astounded him.

"What on earth is it? You look as if you'd been caught stealing a hat," he responded, encouragingly.

The Bishop felt his heart thumping as that healthy organ had not thumped for years. "I feel a bit that way," he gasped. "You remember what we were talking of the other day?"

"The other day—talking—" Fielding looked bewildered. Then his face darkened. "You mean Dick—the affair with that girl." His voice was at once hard and unresponsive. "What about it?"

"Not at all," said the Bishop, complainingly. "Don't misunderstand like that, Dick—it's so much harder."

"Oh!" and Fielding's look cleared. "Well, what is it then, old man? Out with it—want a check for a mission? Surely you don't hesitate to tell me that! Whatever I have is yours, too—you know it."

The Bishop looked deeply disgusted. "Muddlehead!" was his unexpected answer, and Fielding, serene in the consciousness of generosity and good feeling, looked as if a hose had been turned on him.

"What the devil!" he said. "Excuse me, Jim, but just tell me what you're after. I can't make you out."

"It's most difficult." The Bishop seemed to articulate with trouble. "It was so long ago, and I've never spoken of it." Fielding, mouth and eyes wide, watched him as he stumbled on. "There were three of us, you see—though, of course, you didn't know. Nobody knew. She told my mother, that was all.—Oh, I'd no idea how difficult this would be," and the Bishop pushed back his damp hair and gasped again. Suddenly a wave of color rushed over his face.

"No one could help it, Dick," he said. "She was so lovely, so exquisite, so—"

Fielding rose quickly and put his hand on his friend's forehead, "Jim, my dear boy," he said gravely, "this heat has been too much for you. Sit there quietly, while I get some ice. Here, let me loosen your collar," and he put his fingers on the white clerical tie.

Then the Bishop rose up in his wrath and shook him off, and his deep blue eyes flashed fire.

"Let me alone," he said. "It is inexplicable to me how a man can be so dense. Haven't I explained to you in the plainest way what I have never told another soul? Is this the reward I am to have for making the greatest effort I have made for years?" And after a moment's steady, indignant glare at the speechless Fielding he turned and strode in angry majesty through the wide hall doorway.

When he walked out of the same doorway an hour later, on his way to service, Fielding sat back in a shadowy corner and let him pass without a word. He watched critically the broad shoulders and athletic figure as his friend moved down the narrow walk—a body carefully trained to hold well and easily the trained mind within. But the careless energy that was used to radiate from the great elastic muscles seemed lacking to-day, and the erect head drooped. Fielding shook his own head as the Bishop turned the corner and went out of his view.

"'Mens sana in corpore sano,'" he said aloud, and sighed. "He has worked too hard this summer. I never saw him like that. If he should—" and he stopped; then he rose, and looked at his watch and slowly followed the Bishop's steps.

The little church of Saint Peter's-by-the-Sea was filled even on this hot July afternoon, to hear the famous Bishop, and in the half-light that fell through painted windows and lay like a dim violet veil against the gray walls, the congregation with summer gowns and flowery hats, had a billowy effect as of a wave tipped everywhere with foam. Fielding, sitting far back, saw only the white-robed Bishop, and hardly heard the words he said, through listening for the modulations of his voice. He was anxious for the man who was dear to him, and the service and its minister were secondary to-day. But gradually the calm, reverent, well-known tones reassured him, and he yielded to the pleasure of letting his thoughts be led, by the voice that stood to him for goodness, into the spirit of the words that are filled with the beauty of holiness. At last it was time for the sermon, and the Bishop towered in the low stone pulpit and turned half away from them all as he raised one arm high with a quick, sweeping gesture.

"In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost, Amen!" he said, and was still.

A shaft of yellow light fell through a memorial window and struck a golden bar against the white lawn of his surplice, and Fielding, staring at him with eyes of almost passionate devotion, thought suddenly of Sir Galahad, and of that "long beam" down which had "slid the Holy Grail." Surely the flame of that old vigorous Christianity had never burned higher or steadier. A marvellous life for this day, kept, like the flower of Knighthood, strong and beautiful and "unspotted from the world." Fielding sighed as he thought of his own life, full of good impulses, but crowded with mistakes, with worldliness, with lowered ideals, with yieldings to temptation. Then, with a pang, he thought about Dick, about the crisis for him that the next week must bring, and he heard again the Bishop's steady, uncompromising words as they talked on the piazza. And on a wave of selfish feeling rushed back the old excuses. "It is different. It is easy for him to be good. Dick is not his son. He has never been tempted like other men. He never hated Fairfax Preston—he never loved Eleanor Gray." And back somewhere in the dark places of his consciousness began to work a dim thought of his friend's puzzling words of that day: "No one could help loving her—she was so lovely—so exquisite!"

The congregation rustled softly everywhere as the people settled themselves to listen—they listened always to him. And across the hush that followed came the Bishop's voice again, tranquilly breaking, not jarring, the silence. "Not disobedient to the heavenly vision," were the words he was saying, and Fielding dropped at once the thread of his own thought to listen.

He spoke quickly, clearly, in short Anglo-Saxon words—the words that carry their message straightest to hearts red with Saxon blood—of the complex nature of every man—how the angel and the demon live in each and vary through all the shades of good and bad. How yet in each there is always the possibility of a highest and best that can be true for that personality only—a dream to be realized of the lovely life, blooming into its own flower of beauty, that God means each life to be. In his own rushing words he clothed the simple thought of the charge that each one has to keep his angel strong, the white wings free for higher flights that come with growth.

"The vision," he said, "is born with each of us, and though we lose it again and again, yet again and again it comes back and beckons, calls, and the voice thrills us always. And we must follow, or lose the way. Through ice and flame we must follow. And no one may look across where another soul moves on a quick, straight path and think that the way is easier for the other. No one can see if the rocks are not cutting his friend's feet; no one can know what burning lands he has crossed to follow, to be so close to his angel, his messenger. Believe always that every other life has been more tempted, more tried than your own; believe that the lives higher and better than your own are so not through more ease, but more effort; that the lives lower than yours are so through less opportunity, more trial. Believe that your friend with peace in his heart has won it, not happened on it—that he has fought your very fight. So the mist will melt from your eyes and you will see clearer the vision of your life and the way it leads you; selfishness will fall from your shoulders and you will follow lightly. And at the end, and along the way you will have the glory of effort, the joy of fighting and winning, the beauty of the heights where only an ideal can take you."

What more he said Fielding did not hear—for him one sentence had been the final word. The unlaid ghost of the Bishop's puzzling talk an hour before rose up and from its lips came, as if in full explanation, "He has fought your very fight." He sat in his shadowy, dark corner of the cool, little stone church, and while the congregation rose and knelt and sang and prayed, he was still. Piece by piece he fitted the mosaic of past and present, and each bit slipped faultlessly into place. There was no question in his mind now as to the fact, and his manliness and honor rushed to meet the situation. He had said that where his friend had gone he would go. If it was down the road of renunciation of a life-long enmity, he would not break his word. Complex problems resolve themselves at the point of action into such simple axioms. Dick should have a blessing and his sweetheart; he would do his best for Fairfax Preston; with his might he would keep his word. A great sigh and a wrench at his heart as if a physical growth of years were tearing away, and the decision was made. Then, in a mist of pain and effort, and a surprised new freedom from the accustomed pang of hatred, he heard the rustle and movement of a kneeling congregation, and, as he looked, the Bishop raised his arms. Fielding bent his gray head quickly in his hands, and over it, laden with "peace" and "the blessing of God Almighty," as if a general commended his soldier on the field of battle, swept the solemn words of the benediction.

Peace touched the earth on the blue and white September day when Madge and Dick were married. Pearly piled-up clouds, white "herded elephants," lay still against a sparkling sky, and the air was alive like cool wine, and breathing warm breaths of sunlight. No wedding was ever gayer or prettier, from the moment when the smiling holiday crowd in little Saint Peter's caught their breath at the first notes of "Lohengrin" and turned to see Eleanor, white-clad and solemn, and impressed with responsibility, lead the procession slowly up the aisle, her eyes raised to the Bishop's calm face in the chancel, to the moment when, in showers of rice and laughter and slippers, the Fielding carriage dashed down the driveway, and Dick, leaning out, caught for a last picture of his wedding-day, standing apart from the bright colors grouped on the lawn, the black and white of the Bishop and Eleanor, gazing after them, hand in hand.

Bit by bit the brilliant kaleidoscopic effect fell apart and resolved itself into light groups against the dark foliage or flashing masses of carriages and people and horses, and then even the blurs on the distance were gone, and the place was still and the wedding was over. The long afternoon was before them, with its restless emptiness, as if the bride and groom had taken all the reason for life with them.

There were bridesmaids and ushers staying at the Fieldings'. The graceful girl who poured out the Bishop's tea on the piazza, some hours later, and brought it to him with her own hands, stared a little at his face for a moment.

"You look tired, Bishop. Is it hard work marrying people? But you must be used to it after all these years," and her blue eyes fell gently on his gray hair. "So many love-stories you have finished—so many, many!" she went on, and then quite softly, "and yet never to have a love-story of your own!"

At this instant Eleanor, lolling on the arm of his chair, slipped over on his knee and burrowed against his coat a big pink bow that tied her hair. The Bishop's arm tightened around the warm, alive lump of white muslin, and he lifted his face, where lines showed plainly to-day, with a smile like sunshine.

"You are wrong, my daughter. They never finish—they only begin here. And my love-story"—he hesitated and his big fingers spread over the child's head, "It is all written in Eleanor's eyes."

"I hope when mine comes I shall have the luck to hear anything half as pretty as that. I envy Eleanor," said the graceful bridesmaid as she took the tea-cup again, but the Bishop did not hear her.

He had turned toward the sea and his eyes wandered out across the geraniums where the shadow of a sun-filled cloud lay over uncounted acres of unhurried waves. His face was against the little girl's bright head, and he said something softly to himself, and the child turned her face quickly and smiled at him and repeated the words:

"Many waters shall not wash out love," said Eleanor.

"Many waters shall not wash out love," said Eleanor.

The old clergyman sighed and closed the volume of "Browne on The Thirty-nine Articles," and pushed it from him on the table. He could not tell what the words meant; he could not keep his mind tense enough to follow an argument of three sentences. It must be that he was very tired. He looked into the fire, which was burning badly, and about the bare, little, dusty study, and realized suddenly that he was tired all the way through, body and soul. And swiftly, by way of the leak which that admission made in the sea-wall of his courage, rushed in an ocean of depression. It had been a hard, bad day. Two people had given up their pews in the little church which needed so urgently every ounce of support that held it. And the junior warden, the one rich man of the parish, had come in before service in the afternoon to complain of the music. If that knife-edged soprano did not go, he said, he was afraid he should have to go himself; it was impossible to have his nerves scraped to the raw every Sunday.

The old clergyman knew very little about music, but he remembered that his ear had been uncomfortably jarred by sounds from the choir, and that he had turned once and looked at them, and wondered if some one had made a mistake, and who it was. It must be, then, that dear Miss Barlow, who had sung so faithfully in St. John's for twenty-five years, was perhaps growing old. But how could he tell her so; how could he deal such a blow to her kind heart, her simple pride and interest in her work? He was growing old, too.

His sensitive mouth carved downward as he stared into the smoldering fire, and let himself, for this one time out of many times he had resisted, face the facts. It was not Miss Barlow and the poor music; it was not that the church was badly heated, as one of the ex-pewholders had said, nor that it was badly situated, as another had claimed; it was something of deeper, wider significance, a broken foundation, that made the ugly, widening crack all through the height of the tower. It was his own inefficiency. The church was going steadily down, and he was powerless to lift it. His old enthusiasm, devotion, confidence—what had become of them? They seemed to have slipped by slow degrees, through the unsuccessful years, out of his soul, and in their place was a dull distrust of himself; almost—God forgive him—distrust in God's kindness. He had worked with his might all the years of his life, and what he had to show for it was a poor, lukewarm parish, a diminished congregation, debt—to put it in one dreadful word, failure!

He stared into the smoldering fire.

By the pitiless searchlight of hopelessness, he saw himself for the first time as he was—surely devoted and sincere, but narrow, limited, a man lacking outward expression of inward and spiritual grace. He had never had the gift to win hearts. That had not troubled him much, earlier, but lately he had longed for a little appreciation, a little human love, some sign that he had not worked always in vain. He remembered the few times that people had stopped after service to praise his sermons, and to-night he remembered not so much the glow at his heart that the kind words had brought, as the fact that those times had been very few. He did not preach good sermons; he faced that now, unflinchingly. He was not broad minded; new thoughts were unattractive, hard for him to assimilate; he had championed always theories that were going out of fashion, and the half-consciousness of it put him ever on the defensive; when most he wished to be gentle, there was something in his manner which antagonized. As he looked back over his colorless, conscientious past, it seemed to him that his life was a failure. The souls he had reached, the work he had done with such infinite effort—it might all have been done better and easily by another man. He would not begrudge his strength and his years burned freely in the sacred fire, if he might know that the flame had shone even faintly in dark places, that the heat had warmed but a little the hearts of men. But—he smiled grimly at the logs in front of him, in the small, cheap, black marble fireplace—his influence was much like that, he thought, cold, dull, ugly with uncertain smoke. He, who was not worthy, had dared to consecrate himself to a high service, and it was his reasonable punishment that his life had been useless.

Like a stab came back the thought of the junior warden, of the two more empty pews, and then the thought, in irresistible self-pity, of how hard he had tried, how well he had meant, how much he had given up, and he felt his eyes filling with a man's painful, bitter tears. There had been so little beauty, reward, in his whole past. Once, thirty years before, he had gone abroad for six weeks, and he remembered the trip with a thrill of wonder that anything so lovely could have come into his sombre life—the voyage, the bit of travel, the new countries, the old cities, the expansion, broadening of mind he had felt for a time as its result. More than all, the delight of the people whom he had met, the unused experience of being understood at once, of light touch and easy flexibility, possible, as he had not known before, with good and serious qualities. One man, above all, he had never forgotten. It had been a pleasant memory always to have known him, to have been friends with him even, for he had felt to his own surprise and joy that something in him attracted this man of men. He had followed the other's career, a career full of success unabused, of power grandly used, of responsibility lifted with a will. He stood over thousands and ruled rightly—a true prince among men. Somewhat too broad, too free in his thinking—the old clergyman deplored that fault—yet a man might not be perfect. It was pleasant to know that this strong and good soul was in the world and was happy; he had seen him once with his son, and the boy's fine, sensitive face, his honest eyes, and pretty deference of manner, his pride, too, in his distinguished father, were surely a guaranty of happiness. The old man felt a sudden generous gladness that if some lives must be wasted, yet some might be, like this man's whom he had once known, full of beauty and service. It would be good if he might add a drop to the cup of happiness which meant happiness to so many—and then he smiled at his foolish thought. That he should think of helping that other—a man of so little importance to help a man of so much! And suddenly again he felt tears that welled up hotly.

He put his gray head, with its scanty, carefully brushed hair, back against the support of the worn armchair, and shut his eyes to keep them back. He would try not to be cowardly. Then, with the closing of the soul-windows, mental and physical fatigue brought their own gentle healing, and in the cold, little study, bare, even, of many books, with the fire smoldering cheerlessly before him, he fell asleep.

A few miles away, in a suburb of the same great city, in a large library peopled with books, luxurious with pictures and soft-toned rugs and carved dark furniture, a man sat staring into the fire. The six-foot logs crackled and roared up the chimney, and the blaze lighted the wide, dignified room. From the high chimney-piece, that had been the feature of a great hall in Florence two centuries before, grotesque heads of black oak looked down with a gaze which seemed weighted with age-old wisdom and cynicism, at the man's sad face. The glow of the lamp, shining like a huge gray-green jewel, lighted unobtrusively the generous sweep of table at his right hand, and on it were books whose presence meant the thought of a scholar and the broad interests of a man of affairs. Each detail of the great room, if there had been an observer of its quiet perfection, had an importance of its own, yet each exquisite belonging fell swiftly into the dimness of the background of a picture when one saw the man who was the master. Among a thousand picked men, his face and figure would have been distinguished. People did not call him old, for the alertness and force of youth radiated from him, and his gray eyes were clear and his color fresh, yet the face was lined heavily, and the thick thatch of hair shone in the firelight silvery white. Face and figure were full of character and breeding, of life lived to its utmost, of will, responsibility, success. Yet to-night the spring of the mechanism seemed broken, and the noble head lay back against the brown leather of his deep chair as listlessly as a tired girl's. He watched the dry wood of the fire as it blazed and fell apart and blazed up brightly again, yet his eyes did not seem to see it—their absorbed gaze was inward.

The distant door of the room swung open, but the man did not hear, and, his head and face clear cut like a cameo against the dark leather, hands stretched nervelessly along the arms of the chair, eyes gazing gloomily into the heart of the flame, he was still. A young man, brilliant with strength, yet with a worn air about him, and deep circles under his eyes, stood inside the room and looked at him a long minute—those two in the silence. The fire crackled cheerfully and the old man sighed.

"Father!" said the young man by the door.

In a second the whole pose changed, and he sat intense, staring, while the son came toward him and stood across the rug, against the dark wood of the Florentine fireplace, a picture of young manhood which any father would he proud to own.

"Of course, I don't know if you want me, father," he said, "but I've come to tell you that I'll be a good boy, if you do."

The gentle, half-joking manner was very winning, and the play of his words was trembling with earnest. The older man's face shone as if lamps were lighted behind his eyes.

"If I want you, Ted!" he said, and held out his hand.

With a quick step forward the lad caught it, and then, with quick impulsiveness, as if his childhood came back to him on the flood of feeling unashamed, bent down and kissed him. As he stood erect again he laughed a little, but the muscles of his face were working, and there were tears in his eyes. With a swift movement he had drawn a chair, and the two sat quiet a moment, looking at each other in deep and silent content to be there so, together.

"Yesterday I thought I'd never see you again this way," said the boy; and his father only smiled at him, satisfied as yet without words. The son went on, his eager, stirred feelings crowding to his lips. "There isn't any question great enough, there isn't any quarrel big enough, to keep us apart, I think, father. I found that out this afternoon. When a chap has a father like you, who has given him a childhood and a youth like mine—" The young voice stopped, trembling. In a moment he had mastered himself. "I'll probably never be able to talk to you like this again, so I want to say it all now. I want to say that I know, beyond doubt, that you would never decide anything, as I would, on impulse, or prejudice, or from any motives but the highest. I know how well-balanced you are, and how firmly your reason holds your feelings. So it's a question between your judgment and mine—and I'm going to trust yours. You may know me better than I know myself, and anyway you're more to me than any career, though I did think—but we won't discuss it again. It would have been a tremendous risk, of course, and it shall be as you say. I found out this afternoon how much of my life you were," he repeated.

The older man kept his eyes fixed on the dark, sensitive, glowing young face, as if they were thirsty for the sight. "What do you mean by finding it out this afternoon, Ted? Did anything happen to you?"

The young fellow turned his eyes, that were still a bit wet with the tears, to his father's face, and they shone like brown stars. "It was a queer thing," he said, earnestly, "It was the sort of thing you read in stories—almost like," he hesitated, "like Providence, you know. I'll tell you about it; see if you don't think so. Two days ago, when I—when I left you, father—I caught a train to the city and went straight to the club, from habit, I suppose, and because I was too dazed and wretched to think. Of course, I found a grist of men there, and they wouldn't let me go. I told them I was ill, but they laughed at me. I don't remember just what I did, for I was in a bad dream, but I was about with them, and more men I knew kept turning up—I couldn't seem to escape my friends. Even if I stayed in my room, they hunted me up. So this morning I shifted to the Oriental, and shut myself up in my room there, and tried to think and plan. But I felt pretty rotten, and I couldn't see daylight, so I went down to lunch, and who should be at the next table but the Dangerfields, the whole outfit, just back from England and bursting with cheerfulness! They made me lunch with them, and it was ghastly to rattle along feeling as I did, but I got away as soon us I decently could—rather sooner, I think—and went for a walk, hoping the air would clear my head. I tramped miles—oh, a long time, but it seemed not to do any good; I felt deadlier and more hopeless than ever—I haven't been very comfortable fighting you," he stopped a minute, and his tired face turned to his father's with a smile of very winning gentleness.

The father tried to speak, but, his voice caught harshly. Then, "We'll make it up, Ted," he said, and laid his hand on the boy's shoulder.

The young fellow, as if that touch had silenced him, gazed into the fire thoughtfully, and the big room was very still for a long minute. Then he looked up brightly.

"I want to tell you the rest. I came back from my tramp by the river drive, and suddenly I saw Griswold on his horse trotting up the bridle-path toward me. I drew the line at seeing any more men, and Griswold is the worst of the lot for wanting to do things, so I turned into a side-street and ran. I had an idea he had seen me, so when I came to a little church with the doors open, in the first half-block, I shot in. Being Lent, you know, there was service going on, and I dropped quietly into a seat at the back, and it came to me in a minute, that I was in fit shape to say my prayers, so—I said 'em. It quieted me a bit, the old words of the service. They're fine English, of course, and I think words get a hold on you when they're associated with every turn of your life. So I felt a little less like a wild beast, by the time the clergyman began his sermon. He was a pathetic old fellow, thin and ascetic and sad, with a narrow forehead and a little white hair, and an underfed look about him. The whole place seemed poor and badly kept. As he walked across the chancel, he stumbled on a hole in the carpet. I stared at him, and suddenly it struck me that he must be about your age, and it was like a knife in me, father, to see him trip. No two men were ever more of a contrast, but through that very fact he seemed to be standing there as a living message from you. So when he opened his mouth to give out his text I fell back as if he had struck me, for the words he said were, 'I will arise and go to my father.'"

The boy's tones, in the press and rush of his little story, were dramatic, swift, and when he brought out its climax, the older man, though his tense muscles were still, drew a sudden breath, as if he, too, had felt a blow. But he said nothing, and the eager young voice went on.

"The skies might have opened and the Lord's finger pointed at me, and I couldn't have felt more shocked. The sermon was mostly tommy-rot, you know—platitudes. You could see that the man wasn't clever—had no grasp—old-fashioned ideas—didn't seem to have read at all. There was really nothing in it, and after a few sentences I didn't listen particularly. But there were two things about it I shall never forget, never, if I live to a hundred. First, all through, at every tone of his voice, there was the thought that the brokenhearted look in the eyes of this man, such a contrast to you in every way possible, might be the very look in your eyes after a while, if I left you. I think I'm not vain to know I make a lot of difference to you, father—considering we two are all alone." There was a questioning inflection, but he smiled, as if he knew.

"You make all the difference. You are the foundation of my life. All the rest counts for nothing beside you." The father's voice was slow and very quiet.

"That thought haunted me," went on the young man, a bit unsteadily, "and the contrast of the old clergyman and you made it seem as if you were there beside me. It sounds unreasonable, but it was so. I looked at him, old, poor, unsuccessful, narrow-minded, with hardly even the dignity of age, and I couldn't help seeing a vision of you, every year of your life a glory to you, with your splendid mind, and splendid body, and all the power and honor and luxury that seem a natural background to you. Proud as I am of you, it seemed cruel, and then it came to my mind like a stab that perhaps without me, your only son, all of that would—well, what you said just now. Would count for nothing—that you would be practically, some day, just a lonely and pathetic old man like that other."

The hand on the boy's shoulder stirred a little. "You thought right, Ted."

"That was one impression the clergyman's sermon made, and the other was simply his beautiful goodness. It shone from him at every syllable, uninspired and uninteresting as they were. You couldn't help knowing that his soul was white as an angel's. Such sincerity, devotion, purity as his couldn't be mistaken. As I realized it, it transfigured the whole place. It made me feel that if that quality—just goodness—could so glorify all the defects of his look and mind and manner, it must be worth while, and I would like to have it. So I knew what was right in my heart—I think you can always know what's right if you want to know—and I just chucked my pride and my stubbornness into the street, and—and I caught the 7:35 train."

The light of renunciation, the exhaustion of wrenching effort, the trembling triumph of hard-won victory, were in the boy's face, and the thought, as he looked at it, dear and familiar in every shadow, that he had never seen spirit shine through clay more transparently. Never in their lives had the two been as close, never had the son so unveiled his soul before. And, as he had said, in all probability never would it be again. To the depth where they stood words could not reach, and again for minutes, only the friendly undertone of the crackling fire stirred the silence of the great room. The sound brought steadiness to the two who sat there, the old hand on the young shoulder yet. After a time, the older man's low and strong tones, a little uneven, a little hard with the effort to be commonplace, which is the first readjustment from deep feeling, seemed to catch the music of the homely accompaniment of the fire.

"It is a queer thing, Ted," he said, "but once, when I was not much older than you, just such an unexpected chance influence made a crisis in my life. I was crossing to England with the deliberate intention of doing something which I knew was wrong. I thought it meant happiness, but I know now it would have meant misery. On the boat was a young clergyman of about my own age making his first, very likely his only, trip abroad. I was thrown with him—we sat next each other at table, and our cabins faced—and something in the man attracted me, a quality such as you speak of in this other, of pure and uncommon goodness. He was much the same sort as your old man, I fancy, not particularly winning, rather narrow, rather limited in brains and in advantages, with a natural distrust of progress and breadth. We talked together often, and one day, I saw, by accident, into the depths of his soul, and knew what he had sacrificed to become a clergyman—it was what meant to him happiness and advancement in life. It had been a desperate effort, that was plain, but it was plain, too, that from the moment he saw what he thought was the right, there had been no hesitation in his mind. And I, with all my wider mental training, my greater breadth—as I looked at it—was going, with my eyes open, to do a wrong because I wished to do it. You and I must be built something alike, Ted, for a touch in the right spot seems to penetrate to the core of us—the one and the other. This man's simple and intense flame of right living, right doing, all unconsciously to himself, burned into me, and all that I had planned to do seemed scorched in that fire—turned to ashes and bitterness. Of course it was not so simple as it sounds. I went through a great deal. But the steady influence for good was beside me through that long passage—we were two weeks—the stronger because it was unconscious, the stronger, I think, too, that it rested on no intellectual basis, but was wholly and purely spiritual—as the confidence of a child might hold a man to his duty where the arguments of a sophist would have no effect. As I say, I went through a great deal. My mind was a battle-field for the powers of good and evil during those two weeks, but the man who was leading the forces of the right never knew it. The outcome was that as soon as I landed I took my passage back on the next boat, which sailed at once. Within a year, within a month almost, I knew that the decision I made then was a turning-point, that to have done otherwise would have meant ruin in more than one way. I tremble now to think how close I was to shipwreck. All that I am, all that I have, I owe more or less directly to that man's unknown influence. The measure of a life is its service. Much opportunity for that, much power has been in my hands, and I have tried to hold it humbly and reverently, remembering that time. I have thought of myself many times us merely the instrument, fitted to its special use, of that consecrated soul."

The voice stopped, and the boy, his wide, shining eyes fixed on his father's face, drew a long breath. In a moment he spoke, and the father knew, as well as if he had said it, how little of his feeling he could put into words.

"It makes you shiver, doesn't it," he said, "to think what effect you may be having on people, and never know it? Both you and I, father—our lives changed, saved—by the influence of two strangers, who hadn't the least idea what they were doing. It frightens you."

"I think it makes you know," said the older man, slowly, "that not your least thought is unimportant; that the radiance of your character shines for good or evil where you go. Our thoughts, our influences, are like birds that fly from us as we walk along the road; one by one, we open our hands and loose them, and they are gone and forgotten, but surely there will be a day when they will come back on white wings or dark like a cloud of witnesses—"

The man stopped, his voice died away softly, and he stared into the blaze with solemn eyes, as if he saw a vision. The boy, suddenly aware again of the strong hand on his shoulder, leaned against it lovingly, and the fire, talking unconcernedly on, was for a long time the only sound in the warmth and stillness and luxury of the great room which held two souls at peace.

At that hour, with the volume of Browne under his outstretched hand, his thin gray hair resting against the worn cloth of the chair, in the bare little study, the old clergyman slept. And as he slept, a wonderful dream came to him. He thought that he had gone from this familiar, hard world, and stood, in his old clothes, with his old discouraged soul, in the light of the infinitely glorious Presence, where he must surely stand at last. And the question was asked him, wordlessly, solemnly:

"Child of mine, what have you made of the life given you?" And he looked down humbly at his shabby self, and answered:

"Lord, nothing. My life is a failure. I worked all day in God's garden, and my plants were twisted and my roses never bloomed. For all my fighting, the weeds grew thicker. I could not learn to make the good things grow, I tried to work rightly, Lord, my Master, but I must have done it all wrong."

And as he stood sorrowful, with no harvest sheaves to offer as witnesses for his toiling, suddenly back of him he heard a marvellous, many-toned, soft whirring, as of innumerable light wings, and over his head flew a countless crowd of silver-white birds, and floated in the air beyond. And as he gazed, surprised, at their loveliness, without speech again it was said to him:

"My child, these are your witnesses. These are the thoughts and the influences which have gone from your mind to other minds through the years of your life." And they were all pure white.

And it was borne in upon him, as if a bandage had been lifted from his eyes, that character was what mattered in the great end; that success, riches, environment, intellect, even, were but the tools the master gave into his servants' hands, and that the honesty of the work was all they must answer for. And again he lifted his eyes to the hovering white birds, and with a great thrill of joy it came to him that he had his offering, too, he had this lovely multitude for a gift to the Master; and, as if the thought had clothed him with glory, he saw his poor black clothes suddenly transfigured to shining garments, and, with a shock, he felt the rush of a long-forgotten feeling, the feeling of youth and strength, beating in a warm glow through his veins. With a sigh of deep happiness, the old man awoke.

A log had fallen, and turning as it fell, the new surface had caught life from the half-dead ashes, and had blazed up brightly, and the warmth was penetrating gratefully through him. The old clergyman smiled, and held his thin hands to the flame as he gazed into the fire, but the wonder and awe of his dream were in his eyes.

"My beautiful white birds!" he said, aloud, but softly. "Mine! They were out of sight, but they were there all the time. Surely the dream was sent from Heaven—surely the Lord means me to believe that my life has been of service after all." And as he still gazed, with rapt face, into his study fire, he whispered: "Angels came and ministered unto him."

The room was filled with signs of breeding and cultivation; it was bare of the things which mean money. Books were everywhere; family portraits, gone brown with time, hung on the walls; a tall silver candlestick gleamed from a corner; there was the tarnished gold of carved Florentine frames, such as people bring still from Italy. But the furniture-covering was faded, the carpet had been turned, the place itself was the small parlor of a cheap apartment, and the wall-paper was atrocious. The least thoughtful, listening for a moment to that language which a room speaks of those who live in it, would have known this at once as the home of well-bred people who were very poor.

So quiet it was that it seemed empty. If an observer had stood in the doorway, it might have been a minute before he saw that a man sat in front of the fireless hearth with his arms stretched before him on the table and his head fallen into them. For many minutes there was no sound, no stir of the man's nerveless pose; it might have been that he was asleep. Suddenly the characterless silence of the place was flooded with tragedy, for the man groaned, and a child would have known that the sound came from a torn soul. He lifted his face—a handsome, high-bred face, clever, a bit weak,—and tears were wet on his cheeks. He glanced about as if fearing to be seen as he wiped them away, and at the moment there was a light bustle, low voices down the hall. The young man sprang to his feet and stood alert as a step came toward him. He caught a sharp breath as another man, iron-gray, professional, stood in the doorway.

"Doctor! You have made the examination—you think—" he flung at the newcomer, and the other answered with the cool incisive manner of one whose words weigh.

"Mr. Newbold," he said, "when you came to my office this morning I told you my conjectures and my fear. I need not, therefore, go into details again. I am very sorry to have to say to you—" he stopped, and looked at the younger man kindly. "I wish I might make it easier, but it is better that I should tell you that your mother's condition is as I expected."

Newbold gave way a step as if under a blow, and his color went gray. The doctor had seen souls laid bare before, yet he turned his eyes to the floor as the muscles pulled and strained in this young face. It seemed minutes that the two faced each other in the loaded silence, the doctor gazing gravely at the worn carpet, the other struggling for self-control. At last Newbold spoke, in the harsh tone which often comes first after great emotion.

"You mean that there is—no hope?"

And the doctor, relieved at the loosening of the tension, answered readily, glad to merge his humanity in his professional capacity: "No, Mr. Newbold; I do not mean just that. It is this bleak climate, the raw winds from the lake, which make it impossible for your mother to take the first step which might lead to recovery. There is, in fact—" he hesitated. "I may say that there is no hope for her cure while here. But if she is taken to a warm climate at once—at once—within two weeks—and kept there until summer, then, although I have not the gift of prophecy, yet I believe she would be in time a well woman. No medicine, can do it, but out-of-doors and warmth would do it—probably."

He put out his hand with a smile. "I am indeed glad that I may temper judgment with mercy," he said. "Try the south, Mr. Newbold,—try Bermuda, for instance. The sea air and the warmth there might set your mother up marvellously." And as the young man stared at him unresponsively he gave a grasp to the hand he held, and turning, found his way out alone. He stumbled down the dark steps of the third-rate apartment-house and into his brougham, and as the rubber tires bowled him over the asphalt he communed with himself: