CURRENT HISTORY

A MONTHLY MAGAZINE

THE EUROPEAN WAR

VOLUME II.

From the Beginning to March, 1915

With Index

Number 1, April, 1915

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: New York Times Current History: The European War, Vol 2, No. 1, April, 1915

April-September, 1915

Author: Various

Release Date: March 27, 2005 [eBook #15478]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NEW YORK TIMES CURRENT HISTORY: THE EUROPEAN WAR, VOL 2, NO. 1, APRIL, 1915***

H.M. Hussein Kemal—The New Sultan of Egypt,

Which Was Recently Declared a British Protectorate

The Russian Royal Family—The Children of the Czar Have Inherited the Regal Beauty of Their Mother—(Photo from Paul Thompson)

A Monthly Magazine

April, 1915 - September, 1915

BERLIN, Feb. 4, (by wireless to Sayville, L.I.)—The German Admiralty today issued the following communication:

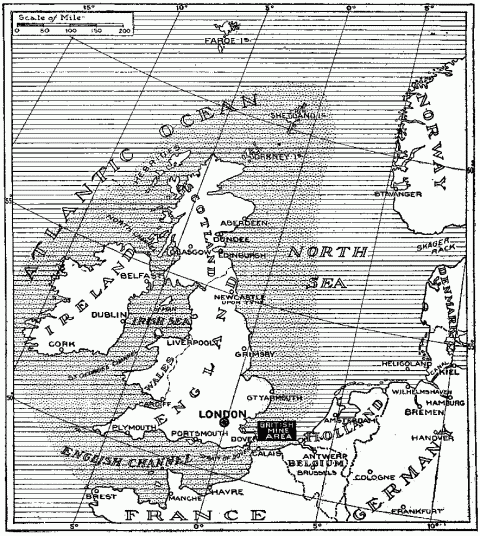

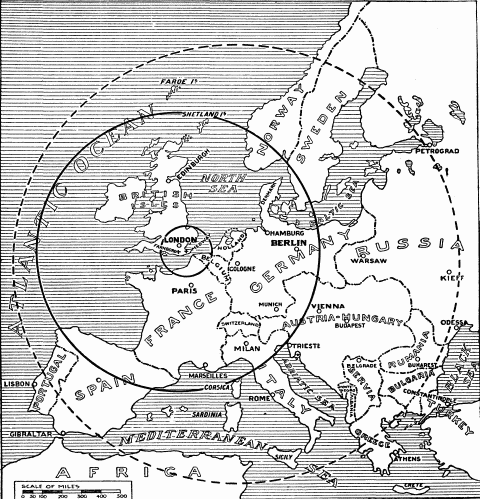

The waters around Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole English Channel, are declared a war zone on and after Feb. 18, 1915.

Every enemy merchant ship found in this war zone will be destroyed, even if it is impossible to avert dangers which threaten the crew and passengers.

Also neutral ships in the war zone are in danger, as in consequence of the misuse of neutral flags ordered by the British Government on Jan. 31, and in view of the hazards of naval warfare, it cannot always be avoided that attacks meant for enemy ships endanger neutral ships.

Shipping northward, around the Shetland Islands, in the eastern basin of the North Sea, and a strip of at least thirty nautical miles in breadth along the Dutch coast, is endangered in the same way.

Feb. 10, 1915.

The Secretary of State has instructed Ambassador Gerard at Berlin to present to the German Government a note to the following effect:

The Government of the United States, having had its attention directed to the proclamation of the German Admiralty, issued on the 4th of February, that the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, are to be considered as comprised within the seat of war; that all enemy merchant vessels found in those waters after the 18th inst. will be destroyed, although it may not always be possible to save crews and passengers; and that neutral vessels expose themselves to danger within this zone of war because, in view of the misuse of neutral flags said to have been ordered by the British Government on the 31st of January and of the contingencies of maritime warfare, it may not be possible always to exempt neutral vessels from attacks intended to strike enemy ships, feels it to be its duty to call the attention of the Imperial German Government, with sincere respect and the most friendly sentiments, but very candidly and earnestly, to the very serious possibilities of the course of action apparently contemplated under that proclamation.

The Government of the United States views those possibilities with such grave concern that it feels it to be its privilege, and, indeed, its duty, in the circumstances to request the Imperial German Government to consider before action is taken the critical situation in respect of the relation between this country and Germany which might arise were the German naval forces, in carrying out the policy foreshadowed in the Admiralty's proclamation, to destroy any merchant vessel of the United States or cause the death of American citizens.

It is, of course, not necessary to remind the German Government that the sole right of a belligerent in dealing with neutral vessels on the high seas is limited to visit and search, unless a blockade is proclaimed and effectively maintained, which this Government does not understand to be proposed in this case. To declare or exercise a right to attack and destroy any vessel entering a prescribed area of the high seas without first certainly determining its belligerent nationality and the contraband character of its cargo would be an act so unprecedented in naval warfare that this Government is reluctant to believe that the Imperial Government of Germany in this case contemplates it as possible.

The suspicion that enemy ships are using neutral flags improperly can create no just presumption that all ships traversing a prescribed area are subject to the same suspicion. It is to determine exactly such questions that this Government understands the right of visit and search to have been recognized.

This Government has carefully noted the explanatory statement issued by the Imperial German Government at the same time with the proclamation of the German Admiralty, and takes this occasion to remind the Imperial German Government very respectfully that the Government of the United States is open to none of the criticisms for unneutral action to which the German Government believes the Governments of certain other neutral nations have laid themselves open; that the Government of the United States has not consented to or acquiesced in any measures which may have been taken by the other belligerent nations in the present war which operate to restrain neutral trade, but has, on the contrary, taken in all such matters a position which warrants it in holding those Governments responsible in the proper way for any untoward effects on American shipping which the accepted principles of international law do not justify; and that it, therefore, regards itself as free in the present instance to take with a clear conscience and upon accepted principles the position indicated in this note.

If the commanders of German vessels of war should act upon the presumption that the flag of the United States was not being used in good faith and should destroy on the high seas an American vessel or the lives of American citizens, it would be difficult for the Government of the United States to view the act in any other light than as an indefensible violation of neutral rights, which it would be very hard, indeed, to reconcile with the friendly relations now happily subsisting between the two Governments.

If such a deplorable situation should arise, the Imperial German Government can readily appreciate that the Government of the United States would be constrained to hold the Imperial Government of Germany to a strict accountability for such acts of their naval authorities, and to take any steps it might be necessary to take to safeguard American lives and property and to secure to American citizens the full enjoyment of their acknowledged rights on the high seas.

The Government of the United States, in view of these considerations, which it urges with the greatest respect and with the sincere purpose of making sure that no misunderstandings may arise, and no circumstances occur, that might even cloud the intercourse of the two Governments, expresses the confident hope and expectation that the Imperial German Government can and will give assurance that American citizens and their vessels will not be molested by the naval forces of Germany otherwise than by visit and search, though their vessels may be traversing the sea area delimited in the proclamation of the German Admiralty. It is stated for the information of the Imperial Government that representations have been made to his Britannic Majesty's Government in respect to the unwarranted use of the American flag for the protection of British ships.

Feb. 10, 1915.

The Secretary of State has instructed Ambassador Page at London to present to the British Government a note to the following effect:

The department has been advised of the declaration of the German Admiralty on Feb. 4, indicating that the British Government had on Jan. 31 explicitly authorized the use of neutral flags on British merchant vessels, presumably for the purpose of avoiding recognition by German naval forces. The department's attention has also been directed to reports in the press that the Captain of the Lusitania, acting upon orders or information received from the British authorities, raised the American flag as his vessel approached the British coasts, in order to escape anticipated attacks by German submarines. Today's press reports also contain an alleged official statement of the Foreign Office defending the use of the flag of a neutral country by a belligerent vessel in order to escape capture or attack by an enemy.

Assuming that the foregoing reports are true, the Government of the United States, reserving for future consideration the legality and propriety of the deceptive use of the flag of a neutral power in any case for the purpose of avoiding capture, desires very respectfully to point out to his Britannic Majesty's Government the serious consequences which may result to American vessels and American citizens if this practice is continued.

The occasional use of the flag of a neutral or an enemy under the stress of immediate pursuit and to deceive an approaching enemy, which appears by the press reports to be represented as the precedent and justification used to support this action, seems to this Government a very different thing from an explicit sanction by a belligerent Government for its merchant ships generally to fly the flag of a neutral power within certain portions of the high seas which are presumed to be frequented with hostile warships. The formal declaration of such a policy of general misuse of a neutral's flag jeopardizes the vessels of the neutral visiting those waters in a peculiar degree by raising the presumption that they are of belligerent nationality regardless of the flag which they may carry.

In view of the announced purpose of the German Admiralty to engage in active naval operations in certain delimited sea areas adjacent to the coasts of Great Britain and Ireland, the Government of the United States would view with anxious solicitude any general use of the flag of the United States by British vessels traversing those waters. A policy such as the one which his Majesty's Government is said to intend to adopt would, if the declaration of the German Admiralty be put in force, it seems clear, afford no protection to British vessels, while it would be a serious and constant menace to the lives and vessels of American citizens.

The Government of the United States, therefore, trusts that his Majesty's Government will do all in their power to restrain vessels of British nationality in the deceptive use of the United States flag in the sea area defined by the German declaration, since such practice would greatly endanger the vessels of a friendly power navigating those waters and would even seem to impose upon the Government of Great Britain a measure of responsibility for the loss of American lives and vessels in case of an attack by a German naval force.

You will impress upon his Majesty's Government the grave concern which this Government feels in the circumstances in regard to the safety of American vessels and lives in the war zone declared by the German Admiralty.

You may add that this Government is making earnest representations to the German Government in regard to the danger to American vessels and citizens if the declaration of the German Admiralty is put into effect.

BERLIN, (via London,) Feb. 18.—German Government's reply to the American note follows:

The Imperial Government has examined the communication from the United States Government in the same spirit of good-will and friendship by which the communication appears to have been dictated. The Imperial Government is in accord with the United States Government that for both parties it is in a high degree desirable to avoid misunderstandings which might arise from measures announced by the German Admiralty and to provide against the occurrence of incidents which might trouble the friendly relations which so far happily exist between the two Governments.

With regard to the assuring of these friendly relations, the German Government believes that it may all the more reckon on a full understanding with the United States, as the procedure announced by the German Admiralty, which was fully explained in the note of the 4th inst., is in no way directed against legitimate commerce and legitimate shipping of neutrals, but represents solely a measure of self-defense, imposed on Germany by her vital interests, against England's method of warfare, which is contrary to international law, and which so far no protest by neutrals has succeeded in bringing back to the generally recognized principles of law as existing before the outbreak of war.

In order to exclude all doubt regarding these cardinal points, the German Government once more begs leave to state how things stand. Until now Germany has scrupulously observed valid international rules regarding naval warfare. At the very beginning of the war Germany immediately agreed to the proposal of the American Government to ratify the new Declaration of London, and took over its contents unaltered, and without formal obligation, into her prize law.

The German Government has obeyed these rules, even when they were diametrically opposed to her military interests. For instance, Germany allowed the transportation of provisions to England from Denmark until today, though she was well able, by her sea forces, to prevent it. In contradistinction to this attitude, England has not even hesitated at a second infringement of international law, if by such means she could paralyze the peaceful commerce of Germany with neutrals. The German Government will be the less obliged to enter into details, as these are put down sufficiently, though not exhaustively, in the American note to the British Government dated Dec. 29, as a result of five months' experience.

All these encroachments have been made, as has been admitted, in order to cut off all supplies from Germany and thereby starve her peaceful civil population—a procedure contrary to all humanitarian principles. Neutrals have been unable to prevent the interruption of their commerce with Germany, which is contrary to international laws.

The American Government, as Germany readily acknowledges, has protested against the British procedure. In spite of these protests and protests from other neutral States, Great Britain could not be induced to depart from the course of action she had decided upon. Thus, for instance, the American ship Wilhelmina recently was stopped by the British, although her cargo was destined solely for the German civil population, and, according to the express declaration of the German Government, was to be employed only for this purpose.

Germany is as good as cut off from her overseas supply by the silent or protesting toleration of neutrals, not only in regard to such goods as are absolute contraband, but also in regard to such as, according to acknowledged law before the war, are only conditional contraband or not contraband at all. Great Britain, on the other hand, is, with the toleration of neutral Governments, not only supplied with such goods as are not contraband or only conditional contraband, but with goods which are regarded by Great Britain, if sent to Germany, as absolute contraband, namely, provisions, industrial raw materials, &c., and even with goods which have always indubitably been regarded as absolute contraband.

The German Government feels itself obliged to point out with the greatest emphasis that a traffic in arms, estimated at many hundreds of millions, is being carried on between American firms and Germany's enemies. Germany fully comprehends that the practice of right and the toleration of wrong on the part of neutrals are matters absolutely at the discretion of neutrals, and involve no formal violation of neutrality. Germany, therefore, did not complain of any formal violation of neutrality, but the German Government, in view of complete evidence before it, cannot help pointing out that it, together with the entire public opinion of Germany, feels itself to be severely prejudiced by the fact that neutrals, in safeguarding their rights in legitimate commerce with Germany according to international law, have up to the present achieved no, or only insignificant, results, while they are making unlimited use of their right by carrying on contraband traffic with Great Britain and our other enemies.

If it is a formal right of neutrals to take no steps to protect their legitimate trade with Germany, and even to allow themselves to be influenced in the direction of the conscious and willful restriction of their trade, on the other hand, they have the perfect right, which they unfortunately do not exercise, to cease contraband trade, especially in arms, with Germany's enemies.

In view of this situation, Germany, after six months of patient waiting, sees herself obliged to answer Great Britain's murderous method of naval warfare with sharp counter-measures. If Great Britain in her fight against Germany summons hunger as an ally, for the purpose of imposing upon a civilized people of 70,000,000 the choice between destitution and starvation or submission to Great Britain's commercial will, then Germany today is determined to take up the gauntlet and appeal to similar allies.

Germany trusts that the neutrals, who so far have submitted to the disadvantageous consequences of Great Britain's hunger war in silence, or merely in registering a protest, will display toward Germany no smaller measure of toleration, even if German measures, like those of Great Britain, present new terrors of naval warfare.

Moreover, the German Government is resolved to suppress with all the means at its disposal the importation of war material to Great Britain and her allies, and she takes it for granted that neutral Governments, which so far have taken no steps against the traffic in arms with Germany's enemies, will not oppose forcible suppression by Germany of this trade.

Acting from this point of view, the German Admiralty proclaimed a naval war zone, whose limits it exactly defined. Germany, so far as possible, will seek to close this war zone with mines, and will also endeavor to destroy hostile merchant vessels in every other way. While the German Government, in taking action based upon this overpowering point of view, keeps itself far removed from all intentional destruction of neutral lives and property, on the other hand, it does not fail to recognize that from the action to be taken against Great Britain dangers arise which threaten all trade within the war zone, without distinction. This a natural result of mine warfare, which, even under the strictest observance of the limits of international law, endangers every ship approaching the mine area. The German Government considers itself entitled to hope that all neutrals will acquiesce in these measures, as they have done in the case of the grievous damages inflicted upon them by British measures, all the more so as Germany is resolved, for the protection of neutral shipping even in the naval war zone, to do everything which is at all compatible with the attainment of this object.

In view of the fact that Germany gave the first proof of her good-will in fixing a time limit of not less than fourteen days before the execution of said measures, so that neutral shipping might have an opportunity of making arrangements to avoid threatening danger, this can most surely be achieved by remaining away from the naval war zone. Neutral vessels which, despite this ample notice, which greatly affects the achievement of our aims in our war against Great Britain, enter these closed waters will themselves bear the responsibility for any unfortunate accidents that may occur. Germany disclaims all responsibility for such accidents and their consequences.

Germany has further expressly announced the destruction of all enemy merchant vessels found within the war zone, but not the destruction of all merchant vessels, as the United States seems erroneously to have understood. This restriction which Germany imposes upon itself is prejudicial to the aim of our warfare, especially as in the application of the conception of contraband practiced by Great Britain toward Germany—which conception will now also be similarly interpreted by Germany—the presumption will be that neutral ships have contraband aboard. Germany naturally is unwilling to renounce its rights to ascertain the presence of contraband in neutral vessels, and in certain cases to draw conclusions therefrom.

Germany is ready, finally, to deliberate with the United States concerning any measures which might secure the safety of legitimate shipping of neutrals in the war zone. Germany cannot, however, forbear to point out that all its efforts in this direction may be rendered very difficult by two circumstances: First, the misuse of neutral flags by British merchant vessels, which is indubitably known to the United States; second, the contraband trade already mentioned, especially in war materials, on neutral vessels.

Regarding the latter point, Germany would fain hope that the United States, after further consideration, will come to a conclusion corresponding to the spirit of real neutrality. Regarding the first point, the secret order of the British Admiralty, recommending to British merchant ships the use of neutral flags, has been communicated by Germany to the United States and confirmed by communication with the British Foreign Office, which designates this procedure as entirely unobjectionable and in accordance with British law. British merchant shipping immediately followed this advice, as doubtless is known to the American Government from the incidents of the Lusitania and the Laertes.

Moreover, the British Government has supplied arms to British merchant ships and instructed them forcibly to resist German submarines. In these circumstances, it would be very difficult for submarines to recognize neutral merchant ships, for search in most cases cannot be undertaken, seeing that in the case of a disguised British ship from which an attack may be expected the searching party and the submarine would be exposed to destruction.

Great Britain, then, was in a position to make the German measures illusory if the British merchant fleet persisted in the misuse of neutral flags and neutral ships could not otherwise be recognized beyond doubt. Germany, however, being in a state of necessity, wherein she was placed by violation of law, must render effective her measures in all circumstances, in order thereby to compel her adversary to adopt methods of warfare corresponding with international law, and so to restore the freedom of the seas, of which Germany at all times is the defender and for which she today is fighting.

Germany therefore rejoices that the United States has made representations to Great Britain concerning the illegal use of their flag, and expresses the expectation that this procedure will force Great Britain to respect the American flag in the future. In this expectation, commanders of German submarines have been instructed, as already mentioned in the note of Feb. 4, to refrain from violent action against American merchant vessels, so far as these can be recognized.

In order to prevent in the surest manner the consequences of confusion—though naturally not so far as mines are concerned—Germany recommends that the United States make its ships which are conveying peaceful cargoes through the British war zone discernible by means of convoys.

Germany believes it may act on the supposition that only such ships would be convoyed as carried goods not regarded as contraband according to the British interpretation made in the case of Germany.

How this method of convoy can be carried out is a question concerning which Germany is ready to open negotiations with the United States as soon as possible. Germany would be particularly grateful, however, if the United States would urgently recommend to its merchant vessels to avoid the British naval war zone, in any case until the settlement of the flag question. Germany is inclined to the confident hope that the United States will be able to appreciate in its entire significance the heavy battle which Germany is waging for existence, and that from the foregoing explanations and promises it will acquire full understanding of the motives and the aims of the measures announced by Germany.

Germany repeats that it has now resolved upon the projected measures only under the strongest necessity of national self-defense, such measures having been deferred out of consideration for neutrals.

If the United States, in view of the weight which it is justified in throwing and able to throw into the scales of the fate of peoples, should succeed at the last moment in removing the grounds which make that procedure an obligatory duty for Germany, and if the American Government, in particular, should find a way to make the Declaration of London respected—on behalf, also, of those powers which are fighting on Germany's side—and there by make possible for Germany legitimate importation of the necessaries of life and industrial raw material, then the German Government could not too highly appreciate such a service, rendered in the interests of humane methods of warfare, and would gladly draw conclusions from the new situation.

LONDON, Feb. 19.—The full text of Great Britain's note regarding the flag, as handed to the American Ambassador, follows:

The memorandum communicated on the 11th of February calls attention in courteous and friendly terms to the action of the Captain of the British steamer Lusitania in raising the flag of the United States of America when approaching British waters, and says that the Government of the United States feels certain anxiety in considering the possibility of any general use of the flag of the United States by British vessels traversing those waters, since the effect of such a policy might be to bring about a menace to the lives and vessels of United States citizens.

It was understood that the German Government announced their intention of sinking British merchant vessels at sight by torpedoes, without giving any opportunity of making any provision for the saving of the lives of non-combatant crews and passengers. It was in consequence of this threat that the Lusitania raised the United States flag on her inward voyage.

On her subsequent outward voyage a request was made by United States passengers, who were embarking on board of her, that the United States flag should be hoisted presumably to insure their safety. Meanwhile, the memorandum from your Excellency had been received. His Majesty's Government did not give any advice to the company as to how to meet this request, and it understood that the Lusitania left Liverpool under the British flag.

It seems unnecessary to say more as regards the Lusitania in particular.

In regard to the use of foreign flags by merchant vessels, the British Merchant Shipping act makes it clear that the use of the British flag by foreign merchant vessels is permitted in time of war for the purpose of escaping capture. It is believed that in the case of some other nations there is similar recognition of the same practice with regard to their flag, and that none of them has forbidden it.

It would, therefore, be unreasonable to expect his Majesty's Government to pass legislation forbidding the use of foreign flags by British merchant vessels to avoid capture by the enemy, now that the German Government have announced their intention to sink merchant vessels at sight with their non-combatant crews, cargoes, and papers, a proceeding hitherto regarded by the opinion of the world not as war, but piracy.

It is felt that the United States Government could not fairly ask the British Government to order British merchant vessels to forgo a means, always hitherto permitted, of escaping not only capture but the much worse fate of sinking and destruction.

Great Britain always has, when a neutral, accorded to vessels of other States at war the liberty to use the British flag as a means of protection against capture, and instances are on record when United States vessels availed themselves of this facility during the American civil war. It would be contrary to fair expectation if now, when conditions are reversed, the United States and neutral nations were to grudge to British ships the liberty to take similar action.

The British Government have no intention of advising their merchant shipping to use foreign flags as a general practice or to resort to them otherwise than for escaping capture or destruction. The obligation upon a belligerent warship to ascertain definitely for itself the nationality and character of a merchant vessel before capturing it, and a fortiori before sinking and destroying it, has been universally recognized.

If that obligation is fulfilled, the hoisting of a neutral flag on board a British vessel cannot possibly endanger neutral shipping, and the British Government holds that if loss to neutrals is caused by disregard of this obligation it is upon the enemy vessel disregarding it and upon the Government giving the orders that it should be disregarded that the sole responsibility for injury to neutrals ought to rest.

LONDON, March 1.—Following is the text of the statement read by Premier Asquith in the House of Commons today and communicated at the same time to the neutral powers in their capitals as an outline of the Allies' policy of retaliation against Germany for her "war zone" decree:

Germany has declared the English Channel, the north and west coasts of France, and the waters around the British Isles a war area, and has officially given notice that all enemy ships found in that area will be destroyed, and that neutral vessels may be exposed to danger.

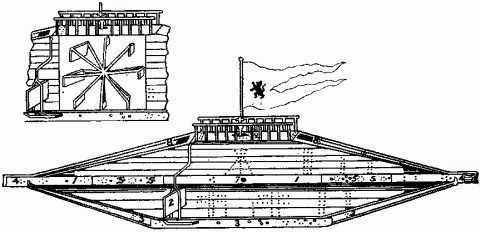

This is, in effect, a claim to torpedo at sight, without regard to the safety of the crew or passengers, any merchant vessel under any flag. As it is not in the power of the German Admiralty to maintain any surface craft in these waters, the attack can only be delivered by submarine agency.

The law and customs of nations in regard to attacks on commerce have always presumed that the first duty of the captor of a merchant vessel is bringing it before a prize court, where it may be tried and where regularities of the capture may be challenged, and where neutrals may recover their cargo.

The sinking of prizes is, in itself, a questionable act, to be resorted to only in extraordinary circumstances, and after provision has been made for the safety of all crews and passengers.

The responsibility of discriminating between neutral and enemy vessels and between neutral and enemy cargoes obviously rests with the attacking ship, whose duty it is to verify the status and character of the vessel and cargo, and to preserve all papers before sinking or capturing the ship. So, also, the humane duty to provide for the safety of crews of merchant vessels, whether neutral or enemy, is an obligation on every belligerent.

It is upon this basis that all previous discussions of law for regulating warfare have proceeded. The German submarine fulfills none of these obligations. She enjoys no local command of the waters wherein she operates. She does not take her captures within the jurisdiction of a prize court. She carries no prize crew which can be put aboard prizes which she seizes. She uses no effective means of discriminating between neutral and enemy vessels. She does not receive on board for safety the crew of the vessel she sinks. Her methods of warfare, therefore, are entirely outside the scope of any international instruments regulating operations against commerce in time of war.

The German declaration substitutes indiscriminate destruction for regulated captures. Germany has adopted this method against the peaceful trader and the non-combatant, with the avowed object of preventing commodities of all kinds, including food for the civilian population, from reaching or leaving the British Isles or Northern France.

Her opponents are, therefore, driven to frame retaliatory measures in order in their turn to prevent commodities of any kind from reaching or leaving Germany.

These measures will, however, be enforced by the British and French Governments without risk to neutral ships or neutral or non-combatant lives, and in strict observation of the dictates of humanity. The British and French Governments will, therefore, hold themselves free to detain and take into port ships carrying goods of presumed enemy destination, ownership, or origin.

It is not intended to confiscate such vessels or cargoes unless they would otherwise be liable to confiscation. Vessels with cargoes which sailed before this date will not be affected.

The first definite statement of the real character of the measures adopted by Great Britain and her allies for restricting the trade of Germany was obtained at Washington on March 17, 1915, when Secretary Bryan made public the text of all the recent notes exchanged between the United States Government and Germany and the Allies regarding the freedom of legitimate American commerce in the war zones. These notes, six in all, show that Great Britain and France stand firm in their announced intention to cut off all trade with Germany. The communications revealed that the United States Government, realizing the difficulties of maintaining an effective blockade by a close guard of an enemy coast on account of the newly developed activity of submarines, asked that "a radius of activity" be defined. Great Britain and France replied with the announcement that the operations of blockade would not be conducted "outside of European waters, including the Mediterranean."

The definition of a "radius of activity" for the allied fleet in European waters, including the Mediterranean, is the first intimation of the geographical limits of the reprisal order. Its limits were not given more exactly, the Allies contend, because Germany was equally indefinite in proclaiming all the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland a "war zone." The measures adopted are those of a blockade against all trade to and from Germany—not the historical kind of blockade recognized in international law, but a new and original form.

The several notes between the United States and the belligerent Governments follow. The stars in the German note mean that as it came to the State Department in cipher certain words were omitted, probably through telegraphic error. In the official text of the note the State Department calls attention to the stars by an asterisk and a footnote saying "apparent omission." In the French note the same thing occurs, and is indicated by the footnote "undecipherable group," meaning that the cipher symbols into which the French note was put by our Embassy in Paris could not be translated back into plain language by the State Department cipher experts. From the context it is apparent that the omitted words in the German note are "insist upon," or words to that effect.

The following identic note was sent by the Secretary of State to the American Ambassadors at London and Berlin:

WASHINGTON, Feb. 20, 1915.

You will please deliver to Sir Edward Grey the following identic note, which we are sending England and Germany:

In view of the correspondence which has passed between this Government and Great Britain and Germany, respectively, relative to the declaration of a war zone by the German Admiralty, and the use of neutral flags by the British merchant vessels, this Government ventures to express the hope that the two belligerent Governments may, through reciprocal concessions, find a basis for agreement which will relieve neutral ships engaged in peaceful commerce from the great dangers which they will incur in the high seas adjacent to the coasts of the belligerents.

The Government of the United States respectfully suggests that an agreement in terms like the following might be entered into. This suggestion is not to be regarded as in any sense a proposal made by this Government, for it of course fully recognizes that it is not its privilege to propose terms of agreement between Great Britain and Germany, even though the matter be one in which it and the people of the United States are directly and deeply interested. It is merely venturing to take the liberty, which it hopes may be accorded a sincere friend desirous of embarrassing neither nation involved, and of serving, if it may, the common interests of humanity. The course outlined is offered in the hope that it may draw forth the views and elicit the suggestions of the British and German Governments on a matter of capital interest to the whole world.

Germany and Great Britain to agree:

First—That neither will sow any floating mines, whether upon the high seas or in territorial waters; that neither will plant on the high seas anchored mines, except within cannon range of harbors for defensive purposes only; and that all mines shall bear the stamp of the Government planting them, and be so constructed as to become harmless if separated from their moorings.

Second—That neither will use submarines to attack merchant vessels of any nationality, except to enforce the right of visit and search.

Third—-That each will require their respective merchant vessels not to use neutral flags for the purpose of disguise or ruse de guerre.

Germany to agree: That all importations of food or foodstuffs from the United States (and from such other neutral countries as may ask it) into Germany shall be consigned to agencies to be designated by the United States Government; that these American agencies shall have entire charge and control without interference on the part of German Government of the receipt and distribution of such importations, and shall distribute them solely to retail dealers bearing licenses from the German Government entitling them to receive and furnish such food and foodstuffs to non-combatants only; that any violation of the terms of the retailers' licenses shall work a forfeiture of their rights to receive such food and foodstuffs for this purpose, and that such food and foodstuffs will not be requisitioned by the German Government for any purpose whatsoever, or be diverted to the use of the armed forces of Germany.

Great Britain to agree: That food and foodstuffs will not be placed upon the absolute contraband list, and that shipments of such commodities will not be interfered with or detained by British authorities, if consigned to agencies designated by the United States Government in Germany for the receipt and distribution of such cargoes to licensed German retailers for distribution solely to the non-combatant population.

In submitting this proposed basis of agreement this Government does not wish to be understood as admitting or denying any belligerent or neutral right established by the principles of international law, but would consider the agreement, if acceptable to the interested powers, a modus vivendi based upon expediency rather than legal right, and as not binding upon the United States either in its present form or in a modified form until accepted by this Government.

BRYAN.

The German reply, handed to the American Ambassador at Berlin, follows:

BERLIN, March 1, 1915.

The undersigned has the honor to inform his Excellency, Mr. James W. Gerard, Ambassador of the United States of America, in reply to the note of the 22d inst., that the Imperial German Government have taken note with great interest of the suggestion of the American Government that certain principles for the conduct of maritime war on the part of Germany and England be agreed upon for the protection of neutral shipping. They see therein new evidence of the friendly feelings of the American Government toward the German Government, which are fully reciprocated by Germany.

It is in accordance with Germany's wishes also to have maritime war conducted according to rules, which, without discriminatingly restricting one or the other of the belligerent powers in the use of their means of warfare, are equally considerate of the interests of neutrals and the dictates of humanity. Consequently it was intimated in the German note of the 16th inst. that observation of the Declaration of London on the part of Germany's adversaries would create a new situation from which the German Government would gladly draw the proper conclusions.

Proceeding from this view, the German Government have carefully examined the suggestion of the American Government and believe that they can actually see in it a suitable basis for the practical solution of the questions which have arisen.

With regard to the various points of the American note, they beg to make the following remarks:

First—With regard to the sowing of mines, the German Government would be willing to agree, as suggested, not to use floating mines and to have anchored mines constructed as indicated. Moreover, they agree to put the stamp of the Government on all mines to be planted. On the other hand, it does not appear to them to be feasible for the belligerents wholly to for ego the use of anchored mines for offensive purposes.

Second—The German Government would undertake not to use their submarines to attack mercantile of any flag except when necessary to enforce the right of visit and search. Should the enemy nationality of the vessel or the presence of contraband be ascertained, submarines would proceed in accordance with the general rules of international law.

Third—As provided in the American note, this restriction of the use of the submarines is contingent on the fact that enemy mercantile abstain from the use of the neutral flag and other neutral distinctive marks. It would appear to be a matter of course that such mercantile vessels also abstain from arming themselves and from all resistance by force, since such procedure contrary to international law would render impossible any action of the submarines in accordance with international law.

Fourth—The regulation of legitimate importations of food into Germany suggested by the American Government appears to be in general acceptable. Such regulation would, of course, be confined to importations by sea, but that would, on the other hand, include indirect importations by way of neutral ports. The German Government would, therefore, be willing to make the declarations of the nature provided in the American note so that the use of the imported food and foodstuffs solely by the non-combatant population would be guaranteed. The Imperial Government must, however, in addition (* * * * *)1 having the importation of other raw material used by the economic system of non-combatants, including forage, permitted. To that end the enemy Governments would have to permit the free entry into Germany of the raw material mentioned in the free list of the Declaration of London, and to treat materials included in the list of conditional contraband according to the same principles as food and foodstuffs.

The German Government venture to hope that the agreement for which the American Government have paved the way may be reached after due consideration of the remarks made above, and that in this way peaceable neutral shipping and trade will not have to suffer any more than is absolutely necessary from the unavoidable effects of maritime war. These effects could be still further reduced if, as was pointed out in the German note of the 16th inst., some way could be found to exclude the shipping of munitions of war from neutral countries to belligerents on ships of any nationality.

The German Government must, of course, reserve a definite statement of their position until such time as they may receive further information from the American Government enabling them to see what obligations the British Government are, on their part, willing to assume.

The undersigned avails himself of this occasion, &c.

VON JAGOW.

Dated, Foreign Office, Berlin, Feb. 28, 1915.

GERARD.

The reply of Great Britain to the American note of Feb. 20, handed to the American Ambassador at London, was as follows:

LONDON, March 15, 1915.

Following is the full text of a memorandum dated March 13, which Grey handed me today:

"On the 22d of February last I received a communication from your Excellency of the identic note addressed to his Majesty's Government and to Germany respecting an agreement on certain points as to the conduct of the war at sea. The reply of the German Government to this note has been published and it is not understood from the reply that the German Government are prepared to abandon the practice of sinking British merchant vessels by submarines, and it is evident from their reply that they will not abandon the use of mines for offensive purposes on the high seas as contrasted with the use of mines for defensive purposes only within cannon range of their own harbors, as suggested by the Government of the United States. This being so, it might appear unnecessary for the British Government to make any further reply than to take note of the German answer.

"We desire, however, to take the opportunity of making a fuller statement of the whole position and of our feeling with regard to it. We recognize with sympathy the desire of the Government of the United States to see the European war conducted in accordance with the previously recognized rules of international law and the dictates of humanity. It is thus that the British forces have conducted the war, and we are not aware that these forces, either naval or military, can have laid to their charge any improper proceedings, either in the conduct of hostilities or in the treatment of prisoners or wounded. On the German side it has been very different.

"1. The treatment of civilian inhabitants in Belgium and the North of France has been made public by the Belgian and French Governments and by those who have had experience of it at first hand. Modern history affords no precedent for the sufferings that have been inflicted on the defenseless and non-combatant population in the territory that has been in German military occupation. Even the food of the population was confiscated until in Belgium an international commission, largely influenced by American generosity and conducted under American auspices, came to the relief of the population and secured from the German Government a promise to spare what food was still left in the country, though the Germans still continue to make levies in money upon the defenseless population for the support of the German Army.

"2. We have from time to time received most terrible accounts of the barbarous treatment to which British officers and soldiers have been exposed after they have been taken prisoner, while being conveyed to German prison camps. One or two instances have already been given to the United States Government founded upon authentic and first-hand evidence which is beyond doubt. Some evidence has been received of the hardships to which British prisoners of war are subjected in the prison camps, contrasting, we believe, most unfavorably with the treatment of German prisoners in this country. We have proposed, with the consent of the United States Government, that a commission of United States officers should be permitted in each country to inspect the treatment of prisoners of war. The United States Government have been unable to obtain any reply from the German Government to this proposal, and we remain in continuing anxiety and apprehension as to the treatment of British prisoners of war in Germany.

"3. At the very outset of the war a German mine layer was discovered laying a mine field on the high seas. Further mine fields have been laid from time to time without warning, and, so far as we know, are still being laid on the high seas, and many neutral as well as British vessels have been sunk by them.

"4. At various times during the war German submarines have stopped and sunk British merchant vessels, thus making the sinking of merchant vessels a general practice, though it was admitted previously, if at all, only as an exception, the general rule to which the British Government have adhered being that merchant vessels, if captured, must be taken before a prize court. In one case already quoted in a note to the United States Government a neutral vessel carrying foodstuffs to an unfortified town in Great Britain has been sunk. Another case is now reported in which a German armed cruiser has sunk an American vessel, the William P. Frye, carrying a cargo of wheat from Seattle to Queenstown. In both cases the cargoes were presumably destined for the civil population. Even the cargoes in such circumstances should not have been condemned without the decision of a prize court, much less should the vessels have been sunk. It is to be noted that both these cases occurred before the detention by the British authorities of the Wilhelmina and her cargo of foodstuffs, which the German Government allege is the justification for their own action.

"The Germans have announced their intention of sinking British merchant vessels by torpedo without notice and without any provision for the safety of the crews. They have already carried out this intention in the case of neutral as well as of British vessels, and a number of non-combatant and innocent lives on British vessels, unarmed and defenseless, have been destroyed in this way.

"5. Unfortified, open, and defenseless towns, such as Scarborough, Yarmouth, and Whitby, have been deliberately and wantonly bombarded by German ships of war, causing in some cases considerable loss of civilian life, including women and children.

"6. German aircraft have dropped bombs on the east coast of England, where there were no military or strategic points to be attacked. On the other hand, I am aware of but two criticisms that have been made on British action in all these respects:

"1. It is said that the British naval authorities also have laid some anchored mines on the high seas. They have done so, but the mines were anchored and so constructed that they would be harmless if they went adrift, and no mines whatever were laid by the British naval authorities till many weeks after the Germans had made a regular practice of laying mines on the high seas.

"2. It is said that the British Government have departed from the view of international law which they had previously maintained, that foodstuffs destined for the civil population should never be interfered with, this charge being founded on the submission to a prize court of the cargo of the Wilhelmina. The special considerations affecting this cargo have already been presented in a memorandum to the United States Government, and I need not repeat them here.

"Inasmuch as the blockade of all foodstuffs is an admitted consequence of blockade, it is obvious that there can be no universal rule based on considerations of morality and humanity which is contrary to this practice. The right to stop foodstuffs destined for the civil population must therefore in any case be admitted if an effective 'cordon' controlling intercourse with the enemy is drawn, announced, and maintained. Moreover, independently of rights arising from belligerent action in the nature of blockade, some other nations, differing from the opinion of the Governments of the United States and Great Britain, have held that to stop the food of the civil population is a natural and legitimate method of bringing pressure to bear on an enemy country as it is upon the defense of a besieged town. It is also upheld on the authority of both Prince Bismarck and Count Caprivi, and therefore presumably is not repugnant to German morality.

"The following are the quotations from Prince Bismarck and Count Caprivi on this point. Prince Bismarck in answering, in 1885, an application from the Kiel Chamber of Commerce for a statement of the view of the German Government on the question of the right to declare as contraband foodstuffs that were not intended for military forces said: 'I reply to the Chamber of Commerce that any disadvantage our commercial and carrying interests may suffer by the treatment of rice as contraband of war does not justify our opposing a measure which it has been thought fit to take in carrying on a foreign war. Every war is a calamity which entails evil consequences not only on the combatants but also on neutrals. These evils may easily be increased by the interference of a neutral power with the way in which a third carries on the war to the disadvantage of the subjects of the interfering power, and by this means German commerce might be weighted with far heavier losses than a transitory prohibition of the rice trade in Chinese waters. The measure in question has for its object the shortening of the war by increasing the difficulties of the enemy and is a justifiable step in war if impartially enforced against all neutral ships.'

"Count Caprivi, during a discussion in the German Reichstag on the 4th of March, 1892, on the subject of the importance of international protection for private property at sea, made the following statements: 'A country may be dependent for her food or for her raw products upon her trade. In fact, it may be absolutely necessary to destroy the enemy's trade.' 'The private introduction of provisions into Paris was prohibited during the siege, and in the same way a nation would be justified in preventing the import of food and raw produce.'

"The Government of Great Britain have frankly declared, in concert with the Government of France, their intention to meet the German attempt to stop all supplies of every kind from leaving or entering British or French ports by themselves stopping supplies going to or from Germany. For this end, the British fleet has instituted a blockade effectively controlling by cruiser 'cordon' all passage to and from Germany by sea. The difference between the two policies is, however, that, while our object is the same as that of Germany, we propose to attain it without sacrificing neutral ships or non-combatant lives, or inflicting upon neutrals the damage that must be entailed when a vessel and its cargo are sunk without notice, examination, or trial.

"I must emphasize again that this measure is a natural and necessary consequence of the unprecedented methods repugnant to all law and morality which have been described above which Germany began to adopt at the very outset of the war and the effects of which have been constantly accumulating."

American Ambassador, London.

The American Government on March 5 transmitted identic messages of inquiry to the Ambassadors at London and Paris inquiring from both England and France how the declarations in the Anglo-French note proclaiming an embargo on all commerce between Germany and neutral countries were to be carried into effect. The message to London was as follows:

WASHINGTON, March 5, 1915.

In regard to the recent communications received from the British and French Governments concerning restraints upon commerce with Germany, please communicate with the British Foreign Office in the sense following:

The difficulty of determining action upon the British and French declarations of intended retaliation upon commerce with Germany lies in the nature of the proposed measures in their relation to commerce by neutrals.

While it appears that the intention is to interfere with and take into custody all ships, both outgoing and incoming, trading with Germany, which is in effect a blockade of German ports, the rule of blockade that a ship attempting to enter or leave a German port, regardless of the character of its cargo, may be condemned is not asserted.

The language of the declaration is "the British and French Governments will, therefore, hold themselves free to detain and take into port ships carrying goods of presumed enemy destination, ownership, or origin. It is not intended to confiscate such vessels or cargoes unless they would otherwise be liable to condemnation."

The first sentence claims a right pertaining only to a state of blockade. The last sentence proposes a treatment of ships and cargoes as if no blockade existed. The two together present a proposed course of action previously unknown to international law.

As a consequence neutrals have no standard by which to measure their rights or to avoid danger to their ships and cargoes. The paradoxical situation thus created should be changed and the declaring powers ought to assert whether they rely upon the rules governing a blockade or the rules applicable when no blockade exists.

The declaration presents other perplexities. The last sentence quoted indicates that the rules of contraband are to be applied to cargoes detained. The rules covering non-contraband articles carried in neutral bottoms is that the cargoes shall be released and the ships allowed to proceed.

This rule cannot, under the first sentence quoted, be applied as to destination. What, then, is to be done with a cargo of non-contraband goods detained under the declaration? The same question may be asked as to conditional contraband cargoes.

The foregoing comments apply to cargoes destined for Germany. Cargoes coming out of German forts present another problem under the terms of the declaration. Under the rules governing enemy exports only goods owned by enemy subjects in enemy bottoms are subject to seizure and condemnation. Yet by the declaration it is purposed to seize and take into port all goods of enemy "ownership and origin." The word "origin" is particularly significant. The origin of goods destined to neutral territory on neutral ships is not, and never has been, a ground for forfeiture, except in case a blockade is declared and maintained. What, then, would the seizure amount to in the present case except to delay the delivery of the goods? The declaration does not indicate what disposition would be made of such cargoes if owned by a neutral or if owned by an enemy subject. Would a different rule be applied according to ownership? If so, upon what principles of international law would it rest? And upon what rule, if no blockade is declared and maintained, could the cargo of a neutral ship sailing out of a German port be condemned? If it is not condemned, what other legal course is there but to release it?

While this Government is fully alive to the possibility that the methods of modern naval warfare, particularly in the use of submarines for both defensive and offensive operations, may make the former means of maintaining a blockade a physical impossibility, it feels that it can be urged with great force that there should be also some limit to "the radius of activity," and especially so if this action by the belligerents can be construed to be a blockade. It would certainly create a serious state of affairs if, for example, an American vessel laden with a cargo of German origin should escape the British patrol in European waters only to be held up by a cruiser off New York and taken into Halifax.

Similar cablegrams sent to Paris.

BRYAN.

The reply from the British Government transmitted by the American Ambassador at London to the Secretary of State concerning the method of enforcing the reprisal order follows:

LONDON, March 15, 1915.

Following is the full text of a note dated today and an Order in Council I have just received from Grey:

"1. His Majesty's Government have had under careful consideration the inquiries which, under instructions from your Government, your Excellency addressed to me on the 8th inst., regarding the scope and mode of application of the measures foreshadowed in the British and French declarations of the 1st of March, for restricting the trade of Germany. Your Excellency explained and illustrated by reference to certain contingencies the difficulty of the United States Government in adopting a definite attitude toward these measures by reason of uncertainty regarding their bearing upon the commerce of neutral countries.

"2. I can at once assure your Excellency that subject to the paramount necessity of restricting German trade his Majesty's Government have made it their first aim to minimize inconvenience to neutral commerce. From the accompanying copy of the Order in Council, which is to be published today, you will observe that a wide discretion is afforded to the prize court in dealing with the trade of neutrals in such manner as may, in the circumstances, be deemed just, and that full provision is made to facilitate claims by persons interested in any goods placed in the custody of the Marshal of the prize court under the order. I apprehend that the perplexities to which your Excellency refers will for the most part be dissipated by the perusal of this document, and that it is only necessary for me to add certain explanatory observations.

"3. The effect of the Order in Council is to confer certain powers upon the executive officers of his Majesty's Government. The extent to which those powers will be actually exercised and the degree of severity with which the measures of blockade authorized will be put into operation are matters which will depend on the administrative orders issued by the Government and the decisions of the authorities specially charged with the duty of dealing with individual ships and cargoes, according to the merits of each case. The United States Government may rest assured that the instructions to be issued by his Majesty's Government to the fleet and customs officials and Executive Committees concerned will impress upon them the duty of acting with the utmost dispatch consistent with the object in view, and of showing in every case such consideration for neutrals as may be compatible with that object, which is, succinctly stated, to establish a blockade to prevent vessels from carrying goods for or coming from Germany."

HERR VON JAGOW—

German Secretary for Foreign Affairs—(Photo from Rogers)

MAXIMILIAN HARDEN—Editor

of Die Zukunft,

Germany's Most Brilliant Journalist, Who Has Been Severe

in His Strictures Upon the United States—(Photo from Brown Bros.)

"4. His Majesty's Government has felt most reluctant, at the moment of initiating a policy of blockade, to exact from neutral ships all the penalties attaching to a breach of blockade. In their desire to alleviate the burden which the existence of a state of war at sea must inevitably impose on neutral sea-borne commerce, they declare their intention to refrain altogether from the exercise of the right to confiscate ships or cargoes which belligerents have always claimed in respect of breaches of blockade. They restrict their claim to the stopping of cargoes destined for or coming from the enemy's territory.

"5. As regards cotton, full particulars of the arrangements contemplated have already been explained. It will be admitted that every possible regard has been had to the legitimate interests of the American cotton trade.

"6. Finally, in reply to the penultimate paragraph of your Excellency's note, I have the honor to state that it is not intended to interfere with neutral vessels carrying enemy cargo of non-contraband nature outside European waters, including the Mediterranean."

(Here follows the text of the Order in Council, which already has been printed.)

American Ambassador, London.

The French Government transmitted the following message:

PARIS, March 14, 1915.

French Government replies as follows:

"In a letter dated March 7 your Excellency was good enough to draw my attention to the views of the Government of the United States regarding the recent communications from the French and British Governments concerning a restriction to be laid upon commerce with Germany. According to your Excellency's letter, the declaration made by the allied Governments presents some uncertainty as regards its application, concerning which the Government of the United States desires to be enlightened in order to determine what attitude it should take.

"At the same time your Excellency notified me that, while granting the possibility of using new methods of retaliation against the new use to which submarines have been put, the Government of the United States was somewhat apprehensive that the allied belligerents might (if their action is to be construed as constituting a blockade) capture in waters near America any ships which might have escaped the cruisers patrolling European waters. In acknowledging receipt of your Excellency's communication I have the honor to inform you that the Government of the republic has not failed to consider this point as presented by the Government of the United States, and I beg to specify clearly the conditions of application, as far as my Government is concerned of the declaration of the allied Governments. As well set forth by the Federal Government, the old methods of blockade cannot be entirely adhered to in view of the use Germany has made of her submarines, and also by reason of the geographical situation of that country. In answer to the challenge to the neutrals as well as to its own adversaries contained in the declaration, by which the German Imperial Government stated that it considered the seas surrounding Great Britain and the French coast on the Channel as a military zone, and warned neutral vessels not to enter the same on account of the danger they would run, the allied Governments have been obliged to examine what measures they could adopt to interrupt all maritime communication with the German Empire and thus keep it blockaded by the naval power of the two allies, at the same time, however, safeguarding as much as possible the legitimate interests of neutral powers and respecting the laws of humanity which no crime of their enemy will induce them to violate.

"The Government of the republic, therefore, reserves to itself the right of bringing into a French or allied port any ship carrying a cargo presumed to be of German origin, destination, or ownership, but it will not go to the length of seizing any neutral ship except in case of contraband. The discharged cargo shall not be confiscated. In the event of a neutral proving his lawful ownership of merchandise destined to Germany, he shall be entirely free to dispose of same, subject to certain conditions. In case the owner of the goods is a German, they shall simply be sequestrated during the war.

"Merchandise of enemy origin shall only be sequestrated when it is at the same time the property of an enemy. Merchandise belonging to neutrals shall be held at the disposal of its owner to be returned to the port of departure.

"As your Excellency will observe, these measures, while depriving the enemy of important resources, respect the rights of neutrals and will not in any way jeopardize private property, as even the enemy owner will only suffer from the suspension of the enjoyment of his rights during the term of hostilities.

"The Government of the republic, being desirous of allowing neutrals every facility to enforce their claims, (here occurred an undecipherable group of words,) give the prize court, an independent tribunal, cognizance of these questions, and in order to give the neutrals as little trouble as possible it has specified that the prize court shall give sentence within eight days, counting from the date on which the case shall have been brought before it.

"I do not doubt, Mr. Ambassador, that the Federal Government, comparing on the one hand the unspeakable violence with which the German Military Government threatens neutrals, the criminal actions unknown in maritime annals already perpetrated against neutral property and ships, and even against the lives of neutral subjects or citizens, and on the other hand the measures adopted by the allied Governments of France and Great Britain, respecting the laws of humanity and the rights of individuals, will readily perceive that the latter have not overstepped their strict rights as belligerents.

"Finally, I am anxious to assure you that it is not and it has never been the intention of the Government of the republic to extend the action of its cruisers against enemy merchandise beyond the European seas, the Mediterranean included."

SHARP.

LONDON, March 15.—The British Order in Council decreeing retaliatory measures on the part of the Government to meet the declaration of the Germans that the waters surrounding the United Kingdom are a military area, was made public today. The text of the order follows:

Whereas, the German Government has issued certain orders which, in violation of the usages of war, purport to declare that the waters surrounding the United Kingdom are a military area in which all British and allied merchant vessels will be destroyed irrespective of the safety and the lives of the passengers and the crews, and in which neutral shipping will be exposed to similar danger in view of the uncertainties of naval warfare, and

Whereas, in the memorandum accompanying the said orders, neutrals are warned against intrusting crews, passengers, or goods to British or allied ships, and

Whereas, such attempts on the part of the enemy give to his Majesty an unquestionable right of retaliation; and

Whereas, his Majesty has therefore decided to adopt further measures in order to prevent commodities of any kind from reaching or leaving Germany, although such measures will be enforced without risk to neutral ships or to neutral or non-combatant life and in strict observance of the dictates of humanity; and

Whereas, the allies of his Majesty are associated with him in the steps now to be announced for restricting further the commerce of Germany, his Majesty is therefore pleased by and with the advice of his Privy Council to order, and it is hereby ordered, as follows:

First—No merchant vessel which sailed from her port of departure after March 1, 1915, shall be allowed to proceed on her voyage to any German port. Unless this vessel receives a pass enabling her to proceed to some neutral or allied port to be named in the pass, the goods on board any such vessel must be discharged in a British port and placed in custody of the Marshal of the prize court. Goods so discharged, if not contraband of war, shall, if not requisitioned for the use of his Majesty, be restored by order of the court and upon such terms as the court may in the circumstances deem to be just to the person entitled thereto.

Second—No merchant vessel which sailed from any German port after March 1, 1915, shall be allowed to proceed on her voyage with any goods on board laden at such port. All goods laden at such port must be discharged in a British or allied port. Goods so discharged in a British port shall be placed in the custody of the Marshal of the prize court, and if not requisitioned for the use of his Majesty shall be detained or sold under the direction of the prize court.

The proceeds of the goods so sold shall be paid into the court and dealt with in such a manner as the court may in the circumstances deem to be just, provided that no proceeds of the sale of such goods shall be paid out of the court until the conclusion of peace, except on the application of a proper officer of the Crown, unless it be shown that the goods had become neutral property before the issue of this order, and provided also that nothing herein shall prevent the release of neutral property, laden at such enemy port, on the application of the proper officer of the Crown.

Third—Every merchant vessel which sailed from her port of departure after March 1, 1915, on her way to a port other than a German port and carrying goods with an enemy destination, or which are enemy property, may be required to discharge such goods in a British or allied port. Any goods so discharged in a British port shall be placed in the custody of the Marshal of the prize court, and unless they are contraband of war shall, if not requisitioned for the use of his Majesty, be restored by an order of the court upon such terms as the court may in the circumstances deem to be just to the person entitled thereto, and provided that this article shall not apply in any case falling within Article 2 or 4 of this order.

Fourth—Every merchant vessel which sailed from a port other than a German port after March 1, 1915, and having on board goods which are of enemy origin, or are enemy property, may be required to discharge such goods in a British or allied port. Goods so discharged in a British port shall be placed in the custody of the Marshal of the prize court, and, if not requisitioned for the use of his Majesty, shall be detained or sold under the direction of the prize court. The proceeds of the goods so sold shall be paid into the court and be dealt with in such a manner as the court may in the circumstances deem to be just, provided that no proceeds of the sale of such goods shall be paid out of the court until the conclusion of peace except on the application of a proper officer of the Crown, unless it be shown that the goods had become neutral property before the issue of this order, and provided also that nothing herein shall prevent the release of neutral property of enemy origin on application of the proper officer of the Crown.

Fifth—Any person claiming to be interested in or to have any claim in respect of any goods not being contraband of war placed in the custody of the Marshal of the prize court under this order, or in the proceeds of such goods, may forthwith issue a writ in the prize court against the proper officer of the Crown and apply for an order that the goods should be restored to him, or that their proceeds should be paid to him, or for such other order as the circumstances of the case may require.

The practice and procedure of the prize court shall, so far as applicable, be followed mutatis mutandis in any proceedings consequential upon this order.

Sixth—A merchant vessel which has cleared for a neutral port from a British or allied port, or which has been allowed to pass as having an ostensible destination to a neutral port and proceeds to an enemy port, shall, if captured on any subsequent voyage be liable to condemnation.

Seventh—Nothing in this order shall be deemed to affect the liability of any vessel or goods to capture or condemnation independently of this order.

Eighth—Nothing in this order shall prevent the relaxation of the provisions of this order in respect of the merchant vessels of any country which declares that no commerce intended for or originating in Germany, or belonging to German subjects, shall enjoy the protection of its flag.

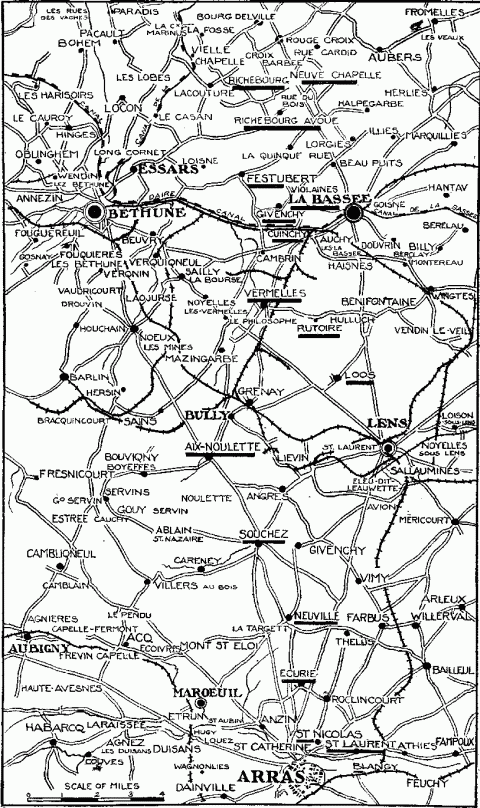

LONDON, March 13.—The Admiralty announced tonight that the British collier Invergyle was torpedoed today off Cresswell, England, and sunk. All aboard were saved.

This brings the total British losses of merchantmen and fishing vessels, either sunk or captured during the war, up to 137. Of these ninety were merchant ships and forty-seven were fishing craft.

A further submarine casualty today was the torpedoing of the Swedish steamer Halma off Scarborough, and the loss of the lives of six of her crew.

The Admiralty announces that since March 10 seven British merchant steamers have been torpedoed by submarines. Two of them, it is stated, were sunk, and of two others it is said that "the sinking is not confirmed." Three were not sunk.

The two steamers officially reported sunk were the Invergyle and the Indian City, which was torpedoed off the Scilly Islands on March 12. The crew of the Indian City was reported rescued.

The two steamers whose reported sinking is not yet officially confirmed are the Florazan, which was torpedoed at the mouth of the Bristol Channel on March 11, all of her crew being landed at Milford Haven, with the exception of one fireman, and the Andalusian, which was attacked off the Scilly Islands on March 12. The crew of the Andalusian is reported to have been rescued.

The Adenwen was torpedoed in the English Channel on March 11, and has since been towed into Cherbourg. Her crew was landed at Brisham.

The steamer Headlands was torpedoed on March 12 off the Scilly Islands. It is reported that her crew was saved. The steamer Hartdale was torpedoed on March 13 off South Rock, in the Irish Channel. Twenty-one of her crew were picked up and two were lost.

Supplementary to the foregoing the Admiralty tonight issued a report giving the total number of British merchant and fishing vessels lost through hostile action from the outbreak of the war to March 10. The statement says that during that period eighty-eight merchant vessels were sunk or captured. Of these fifty-four were victims of hostile cruisers, twelve were destroyed by mines, and twenty-two by submarines. Their gross tonnage totaled 309,945.

In the same period the total arrivals and sailings of overseas steamers of all nationalities of more than 300 tons net were 4,745.

Forty-seven fishing vessels were sunk or captured during this time. Nineteen of these were blown up by mines and twenty-eight were captured by hostile craft. Twenty-four of those captured were caught on Aug. 26, when the Germans raided a fishing fleet.

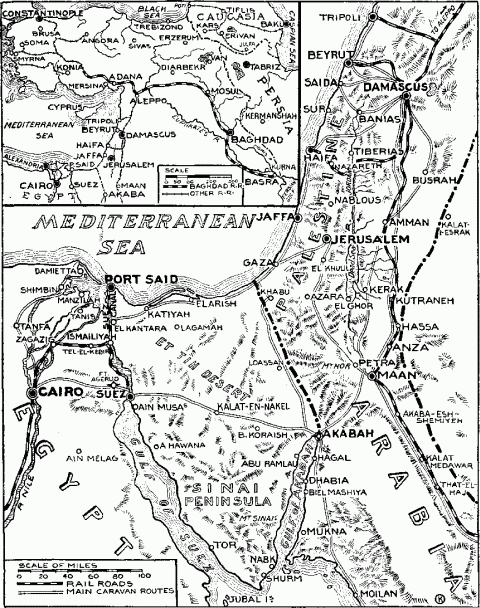

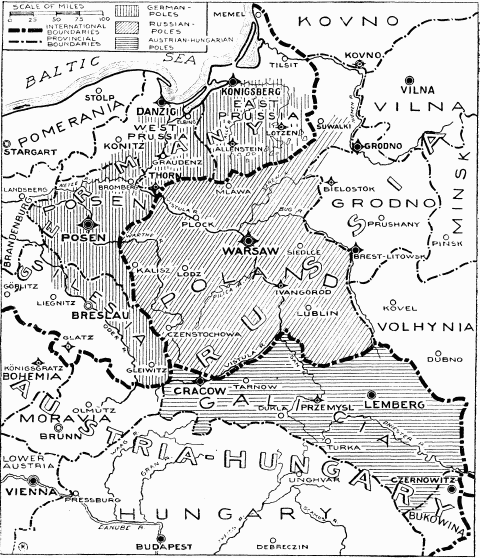

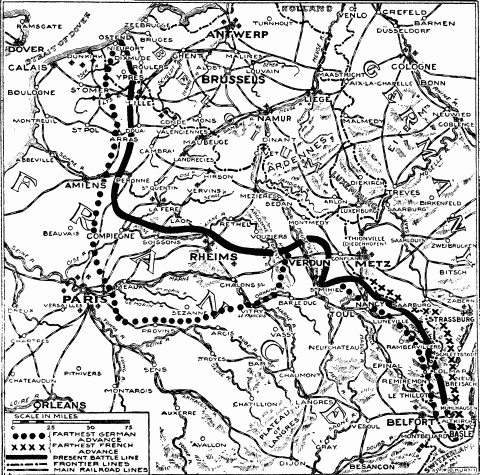

Dotted portion indicates the limits of "War Zone" defined in the German order which became effective Feb. 18, 1915.

By Karl Lamprecht

[Published in New York by the German Information Service, Feb. 3, 1915.]

Denying flatly that the German people were swept blindly and ignorantly into the war by the headlong ambitions of their rulers—the view advanced by Dr. Charles W. Eliot, President Emeritus of Harvard University, and Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler, President of Columbia—Dr. Karl Lamprecht, Professor of History in the University of Leipsic and world-famous German historian, has addressed the open letter which appears below to the two distinguished American scholars. Dr. Lamprecht asserts that under the laws which govern the German Empire the people as citizens have a deciding will in affairs of state and that Germany is engaged in the present conflict because the sober judgment of the German people led them to resort to arms.

Dr. C.W. Eliot, President Emeritus of Harvard University; Dr. N.M. Butler, President of Columbia University.

Gentlemen: I feel confident that you are not in ignorance of my regard and esteem for the great American Republic and its citizens. They have been freely expressed on many occasions and have taken definite form in the journal of my travels through the United States, published in the booklet "Americana," 1905.