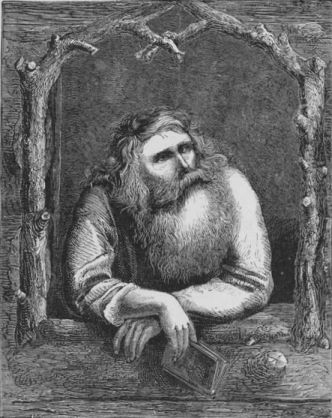

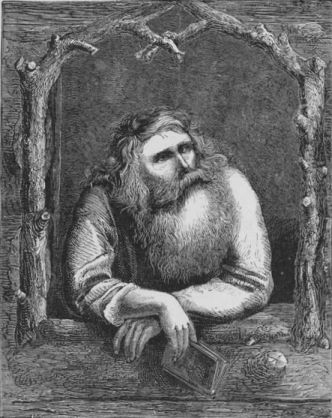

THE BACKWOODS PHILOSOPHER.

(Frontispiece. See page 40.)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The End Of The World, by Edward Eggleston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The End Of The World

A Love Story

Author: Edward Eggleston

Release Date: November 15, 2004 [EBook #14051]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE END OF THE WORLD ***

Produced by Rick Niles, John Hagerson, Charlie Kirschner and the PG

Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

THE BACKWOODS PHILOSOPHER.

(Frontispiece. See page 40.)

It is the pretty unanimous conclusion of book-writers that prefaces are most unnecessary and useless prependages, since nobody reads them. And it is the pretty unanimous practice of book-writers to continue to write them with such pains and elaborateness as would indicate a belief that the success of a book depends upon the favorable prejudice begotten of u graceful preface. My principal embarrassment is that it is not customary for a book to have more than one. How then shall I choose between the half-dozen letters of introduction I might give my story, each better and worse on many accounts than either of the others? I am rather inclined to adopt the following, which might for some reasons be styled the

Perhaps no writer not infatuated with conceit, can send out a book full of thought and feeling which, whatever they may be worth, are his own, without a parental anxiety in regard to the fate of his offspring. And there are few prefaces which do not in some way betray this nervousness. I confess to a respect for even the prefatory doggerel of good Tinker Bunyan--a respect for his paternal tenderness toward his book, not at all for his villainous rhyming. When I saw, the other day, the white handkerchiefs of my children waving an adieu as they sailed away from me, a profound anxiety seized me. So now, as I part company with August and Julia, with my beloved Jonas and my much-respected Cynthy Ann, with the mud-clerk on the Iatan, and the shaggy lord of Shady-Hollow Castle, and the rest, that have watched with me of nights and crossed the ferry with me twice a day for half a year--even now, as I see them waving me adieu with their red silk and "yaller" cotton "hand-kerchers," I know how many rocks of misunderstanding and criticism and how many shoals of damning faint praise are before them, and my heart is full of misgiving.

--But it will never do to have misgivings in a preface. How often have publishers told me this! Ah! if I could write with half the heart and hope my publishers evince in their advertisements, where they talk about "front rank" and "great American story" and all that, it would doubtless be better for the book, provided anybody would read the preface or believe it when they had read it. But at any rate let us not have a preface in the minor key.

A philosophical friend of mine, who is addicted to Carlyle, has recommended that I try the following, which he calls

Why should I try to forestall the Verdict? Is it not foreordained in the very nature of a Book and the Constitution of the Reader that a certain very Definite Number of Readers will misunderstand and dislike a given Book? And that another very Definite Number will understand it and dislike it none the less? And that still a third class, also definitely fixed in the Eternal Nature of Things, will misunderstand and like it, and, what is more, like it only because of their misunderstanding? And in relation to a true Book, there can not fail to be an Elect Few who understand admiringly and understandingly admire. Why, then, make bows, write prefaces, attempt to prejudice the Case? Can I change the Reader? Will I change the Book? No? Then away with Preface! The destiny of the Book is fixed. I can not foretell it, for I am no prophet. But let us not hope to change the Fates by our prefatory bowing and scraping.

--I was forced to confess to my friend who was so kind as to offer to lend me this preface, that there was much truth in it and that truth is nowhere more rare than in prefaces, but it was not possible to adopt it for two reasons: one, that my proof-reader can not abide so many capitals, maintaining that they disfigure the page, and what is a preface of the high philosophical sort worth without a profusion of capitals? Even Carlyle's columns would lose their greatest ornament if their capitals were gone. The second reason for declining to use this preface was that my publishers are not philosophers and would never be content with an "Elect Few," and for my own part the pecuniary interest I have in the copyright renders it quite desirable that as many as possible should be elected to like it, or at least to buy it.

After all it seems a pity that I can not bring myself to use a straightforward

In view of the favor bestowed upon the author's previous story, both by the Public who Criticise and the Public who Buy, it seems a little ungracious to present so soon, another, the scene of which is also laid in the valley of the Ohio. But the picture of Western country life in "The Hoosier School-Master" would not have been complete without this companion-piece, which presents a different phase of it. And indeed there is no provincial life richer in material if only one knew how to get at it.

Nothing is more reverent than a wholesome hatred of hypocrisy. If any man think I have offended against his religion, I must believe that his religion is not what it should be. If anybody shall imagine that this is a work of religious controversy leveled at the Adventists, he will have wholly mistaken my meaning. Literalism and fanaticism are not vices confined to any one sect. They are, unfortunately, pretty widely distributed. However, if--

--And so on.

But why multiply examples of the half-dozen or more that I might, could, would, or should have written? Since everybody is agreed that, nobody reads a preface, I have concluded to let the book go without any.

BROOKLYN, September, 1872.

"And as he [Wordsworth] mingled freely with all kinds of men, he found a pith of sense and a solidity of judgment here and there among the unlearned which he had failed to find in the most lettered; from obscure men he heard high truths.... And love, true love and pure, he found was no flower reared only in what was called refined society, and requiring leisure and polished manners for its growth.... He believed that in country people, what is permanent in human nature, the essential feelings and passions of mankind, exist in greater simplicity and strength."--PRINCIPAL SHAIRP.

It would hardly be in character for me to dedicate this book in good, stiff, old-fashioned tomb-stone style, but I could not have put in the background of scenery without being reminded of the two boys, inseparable as the Siamese twins, who gathered mussel-shells in the river marge, played hide-and-seek in the hollow sycamores, and led a happy life in the shadow of just such hills as those among which the events of this story took place. And all the more that the generous boy who was my playmate then is the generous man who has relieved me of many burdens while I wrote this story, do I feel impelled to dedicate it to GEORGE CARY EGGLESTON, a manly man and a brotherly brother.

"I don't believe that you'd care a cent if she did marry a Dutchman! She might as well as to marry some white folks I know."

Samuel Anderson made no reply. It would be of no use to reply. Shrews are tamed only by silence. Anderson had long since learned that the little shred of influence which remained to him in his own house would disappear whenever his teeth were no longer able to shut his tongue securely in. So now, when his wife poured out this hot lava of argumentum ad hominem, he closed the teeth down in a dead-lock way over the tongue, and compressed the lips tightly over the teeth, and shut his finger-nails into his work-hardened palms. And then, distrusting all these precautions, fearing lest he should be unable to hold on to his temper even with this grip, the little man strode out of the house with his wife's shrill voice in his ears.

Mrs. Anderson had good reason to fear that her daughter was in love with a "Dutchman," as she phrased it in her contempt. The few Germans who had penetrated to the West at that time were looked upon with hardly more favor than the Californians feel for the almond-eyed Chinaman. They were foreigners, who would talk gibberish instead of the plain English which everybody could understand, and they were not yet civilized enough to like the yellow saleratus-biscuit and the "salt-rising" bread of which their neighbors were so fond. Reason enough to hate them!

Only half an hour before this outburst of Mrs. Anderson's, she had set a trap for her daughter Julia, and had fairly caught her.

"Jule! Jule! O Jul-y-e-ee!" she had called.

And Julia, who was down in the garden hoeing a bed in which she meant to plant some "Johnny-Jump-ups," came quickly toward the house, though she know it would be of no use to come quickly. Let her come quickly, or let her come slowly, the rebuke was sure to greet her all the name.

"Why don't you come when you're called, I'd like to know! You're never in reach when you're wanted, and you're good for nothing when you are here!"

Julia Anderson's earliest lesson from her mother's lips had been that she was good for nothing. And every day and almost every hour since had brought her repeated assurances that she was good for nothing. If she had not been good for a great deal, she would long since have been good for nothing as the result of such teaching. But though this was not the first, nor the thousandth, nor the ten thousandth time that she had been told that she was good for nothing, the accustomed insult seemed to sting her now more than ever. Was it that, being almost eighteen, she was beginning to feel the woman blossoming in her nature? Or, was it that the tender words of August Wehle had made her sure that she was good for something, that now her heart felt her mother's insult to be a stale, selfish, ill-natured lie?

"Take this cup of tea over to Mrs. Malcolm's, and tell her that it a'n't quite as good as what I borried of her last week. And tell her that they'll be a new-fangled preacher at the school-house a Sunday, a Millerite or somethin', a preachin' about the end of the world."

Julia did not say "Yes, ma'am," in her usually meek style. She smarted a little yet from the harsh words, and so went away in silence.

Why did she walk fast? Had she noticed that August Wehle, who was "breaking up" her father's north field, was just plowing down the west side of his land? If she hastened, she might reach the cross-fence as he came round to it, and while he was yet hidden from the sight of the house by the turn of the hill. And would not a few words from August Wehle be pleasant to her ears after her mother's sharp depreciation? It is at least safe to conjecture that some such feeling made her hurry through the long, waving timothy of the meadow, and made her cross the log that spanned the brook without ever so much as stopping to look at the minnows glancing about in the water flecked with the sunlight that struggled through the boughs of the water-willows. For, in her thorough loneliness, Julia Anderson had come to love the birds, the squirrels, and the fishes as companions, and in all her life she had never before crossed the meadow brook without stooping to look at the minnows.

All this haste Mrs. Anderson noticed. Having often scolded

Julia for "talking to the fishes like a fool," she noticed the omission. And now she only waited until Julia was over the hill to take the path round the fence under shelter of the blackberry thicket until she came to the clump of alders, from the midst of which she could plainly see if any conversation should take place between her Julia and the comely young Dutchman.

In fact, Julia need not have hurried so much. For August Wehle had kept one eye on his horses and the other on the house all that day. It was the quick look of intelligence between the two at dinner that had aroused the mother's suspicions. And Wehle had noticed the work on the garden-bed, the call to the house, and the starting of Julia on the path toward Mrs. Malcolm's. His face had grown hot, and his hand had trembled. For once he had failed to see the stone in his way, until the plow was thrown clean from the furrow. And when he came to the shade of the butternut-tree by which she must pass, it had seemed to him imperative that the horses should rest. Besides, the hames-string wanted tightening on the bay, and old Dick's throat-latch must need a little fixing. He was not sure that the clevis-pin had not been loosened by the collision with the stone just now. And so, upon one pretext and another, he managed to delay starting his plow until Julia came by, and then, though his heart had counted all her steps from the door-stone to the tree, then he looked up surprised. Nothing could be so astonishing to him as to see her there! For love is needlessly crafty, it has always an instinct of concealment, of indirection about it. The boy, and especially the girl, who will tell the truth frankly in regard to a love affair is a miracle of veracity. But there are such, and they are to be reverenced--with the reverence paid to martyrs.

On her part, Julia Anderson had walked on as though she meant to pass the young plowman by, until he spoke, and then she started, and blushed, and stopped, and nervously broke off the top of a last year's iron-weed and began to break it into bits while he talked, looking down most of the time, but lifting her eyes to his now and then. And to the sun-browned but delicate-faced young German it seemed, a vision of Paradise--every glimpse of that fresh girl's face in the deep shade of the sun-bonnet. For girls' faces can never look so sweet in this generation as they did to the boys who caught sight of them, hidden away, precious things, in the obscurity of a tunnel of pasteboard and calico!

This was not their first love-talk. Were they engaged? Yes, and no. By all the speech their eyes were capable of in school, and of late by words, they were engaged in loving one another, and in telling one another of it. But they were young, and separated by circumstances, and they had hardly begun to think of marriage yet. It was enough for the present to love and be loved. The most delightful stage of a love affair is that in which the present is sufficient and there is no past or future. And so August hung his elbow around the top of the bay horse's hames, and talked to Julia.

It is the highest praise of the German heart that it loves flowers and little children; and like a German and like a lover that he was, August began to speak of the anemones and the violets that were already blooming in the corners of the fence. Girls in love are not apt to say any thing very fresh. And Julia only said she thought the flowers seemed happy in the sunlight In answer to this speech, which seemed to the lover a bit of inspiration, he quoted from Schiller the lines:

"Yet weep, soft children of the Spring;

The feelings Love alone can bring

Have been denied to you!"

With the quick and crafty modesty of her sex, Julia evaded this very pleasant shaft by saying: "How much you know, August! How do you learn it?"

And August was pleased, partly because of the compliment, but chiefly because in saying it Julia had brought the sun-bonnet in such a range that he could see the bright eyes and blushing face at the bottom of this camera-oscura. He did not hasten to reply. While the vision lasted he enjoyed the vision. Not until the sun-bonnet dropped did he take up the answer to her question.

"I don't know much, but what I do know I have learned out of your Uncle Andrew's books."

"Do you know my Uncle Andrew? What a strange man he is! He never comes here, and we never go there, and my mother never speaks to him, and my father doesn't often have anything to say to him. And so you have been at his house. They say he has all up-stairs full of books, and ever so many cats and dogs and birds and squirrels about. But I thought he never let anybody go up-stairs."

"He lets me," said August, when she had ended her speech and dropped her sun-bonnet again out of the range of his eyes, which, in truth, were too steadfast in their gaze. "I spend many evenings up-stairs." August had just a trace of German in his idiom.

"What makes Uncle Andrew so curious, I wonder?"

"I don't exactly know. Some say he was treated not just right by a woman when he was a young man. I don't know. He seems happy. I don't wonder a man should be curious though when a woman that he loves treats him not just right. Any way, if he loves her with all his heart, as I love Jule Anderson!"

These last words came with an effort. And Julia just then remembered her errand, and said, "I must hurry," and, with a country girl's agility, she climbed over the fence before August could help her, and gave him another look through her bonnet-telescope from the other Hide, and then hastened on to return the tea, und to tell Mrs. Malcolm that there was to be a Millerite preacher at the school-house on Sunday night. And August found that his horses were quite cool, while he was quite hot. He cleaned his mold board, and swung his plow round, and then, with a "Whoa! haw!" and a pull upon the single line which Western plowmen use to guide their horses, he drew the team into their place, and set himself to watching the turning of the rich, fragrant black earth. And even as he set his plowshare, so he set his purpose to overcome all obstacles, and to marry Julia Anderson. With the same steady, irresistible, onward course would he overcome all that lay between him and the soul that shone out of the face that dwelt in the bottom of the sun-bonnet.

From her covert in the elder-bushes Mrs. Anderson had seen the parley, and her cheeks had also grown hot, but from a very different emotion. She had not heard the words. She had seen the loitering girl and the loitering plowboy, and she went back to the house vowing that she'd "teach Jule Anderson how to spend her time talking to a Dutchman." And yet the more she thought of it, the more she was satisfied that it wasn't best to "make a fuss" just yet. She might hasten what she wanted to prevent. For though Julia was obedient and mild in word, she was none the less a little stubborn, and in a matter of this sort might take the bit in her teeth.

And so Mrs. Anderson had recourse, as usual, to her husband. She knew she could browbeat him. She demanded that August Wehle should be paid off and discharged. And when Anderson had hesitated, because he feared he could not get another so good a hand, and for other reasons, she burst out into the declaration:

"I don't believe that you'd care a cent if she did marry a Dutchman! She might as well as to marry some white folks I know."

It was settled that August was to be quietly discharged at the end of his month, which was Saturday night. Neither he nor Julia must suspect any opposition to their attachment, nor any discovery of it, indeed. This was settled by Mrs. Anderson. She usually settled things. First, she settled upon the course to be pursued. Then she settled her husband. He always made a show of resistance. His dignity required a show of resistance. But it was only a show. He always meant to surrender in the end. Whenever his wife ceased her fire of small-arms and herself hung out the flag of truce, he instantly capitulated. As in every other dispute, so in this one about the discharge of the "miserable, impudent Dutchman," Mrs. Anderson attacked her husband at all his weak points, and she had learned by heart a catalogue of his weak points. Then, when he was sufficiently galled to be entirely miserable; when she had expressed her regret that she hadn't married somebody with some heart, and that she had ever left her father's house, for her father was always good to her; and when she had sufficiently reminded him of the lover she had given up for him, and of how much he had loved her, and how miserable she had made him by loving Samuel Anderson--when she had conducted the quarrel through all the preliminary stages, she always carried her point in the end by a coup de partie somewhat in this fashion:

"That's just the way! Always the way with you men! I suppose I must give up to you as usual. You've lorded it over me from the start. I can't even have the management of my own daughter. But I do think that after I've let you have your way in so many things, you might turn off that fellow. You might let me have my way in one little thing, and you would if you cared for me. You know how liable I am to die at any moment of heart-disease, and yet you will prolong this excitement in this way."

Now, there is nothing a weak man likes so much as to be considered strong, nothing a henpecked man likes so much as to be regarded a tyrant. If you ever hear a man boast of his determination to rule his own house, you may feel sure that he is subdued. And a henpecked husband always makes a great show of opposing everything that looks toward the enlargement of the work or privileges of women. Such a man insists on the shadow of authority because he can not have the substance. It is a great satisfaction to him that his wife can never be president, and that she can not make speeches in prayer-meeting. While he retains these badges of superiority, he is still in some sense head of the family.

So when Mrs. Anderson loyally reminded her husband that she had always let him have his own way, he believed her because he wanted to, though he could not just at the moment recall the particular instances. And knowing that he must yield, he rather liked to yield as an act of sovereign grace to the poor oppressed wife who begged it.

"Well, if you insist on it, of course, I will not refuse you," he said; "and perhaps you are right." He had yielded in this way almost every day of his married life, and in this way he yielded to the demand that August should he discharged. But he agreed with his wife that Julia should not know anything about it, and that there must be no leave-taking allowed.

The very next day Julia sat sewing on the long porch in front of the house. Cynthy Ann was getting dinner in the kitchen at the other end of the hall, and Mrs. Anderson was busy in her usual battle with dirt. She kept the house clean, because it gratified her combativeness and her domineering disposition to have the house clean in spite of the ever-encroaching dirt. And so she scrubbed and scolded, and scolded and scrubbed, the scrubbing and scolding agreeing in time and rhythm. The scolding was the vocal music, the scrubbing an accompaniment. The concordant discord was perfect. Just at the moment I speak of there was a lull in her scolding. The symphonious scrubbing went on as usual. Julia, wishing to divert the next thunder-storm from herself, erected what she imagined might prove a conversational lightning-rod, by asking a question on a topic foreign to the theme of the last march her mother had played and sung so sweetly with brush and voice.

"Mother, what makes Uncle Andrew so queer?"

"I don't know. He was always queer." This was spoken in a staccato, snapping-turtle way. But when one has lived all one's life with a snapping-turtle, one doesn't mind. Julia did not mind. She was curious to know what was the matter with her uncle, Andrew Anderson. So she said:

"I've heard that some false woman treated him cruelly; is that so?"

Julia did not see how red her mother's face was, for she was not regarding her.

"Who told you that?" Julia was so used to hearing her mother speak in an excited way that she hardly noticed the strange tremor in this question.

"August."

The symphony ceased in a moment. The scrubbing-brush dropped in the pail of soapsuds. But the vocal storm burst forth with a violence that startled even Julia. "August said that, did he? And you listened, did you? You listened to that? You listened to that? You listened to that? Hey? He slandered your mother. You listened to him slander your mother!" By this time Mrs. Anderson was at white heat. Julia was speechless. "I saw you yesterday flirting with that Dutchman, and listening to his abuse of your mother! And now you insult me! Well, to-morrow will be the last day that that Dutchman will hold a plow on this place. And you'd better look out for yourself, miss! You--"

Here followed a volley of epithets which Julia received standing. But when her mother's voice grew to a scream, Julia took the word.

"Mother, hush!"

It was the first word of resistance she had ever uttered. The agony within must have been terrible to have wrung it from her. The mother was stunned with anger and astonishment. She could not recover herself enough to speak until Jule had fled half-way up the stairs. Then her mother covered her defeat by screaming after her, "Go to your own room, you impudent hussy! You know I am liable to die of heart-disease any minute, and you want to kill me!"

Mrs. Anderson felt that she had made a mistake. She had not meant to tell Julia that August was to leave. But now that this stormy scene had taken place, she thought she could make a good use of it. She knew that her husband co-operated with her in her opposition to "the Dutchman," only because he was afraid of his wife. In his heart, Samuel Anderson could not refuse anything to his daughter. Denied any of the happiness which most men find in loving their wives, he found consolation in the love of his daughter. Secretly, as though his paternal affection were a crime, he caressed Julia, and his wife was not long in discovering that the father cared more for a loving daughter than for a shrewish wife. She watched him jealously, and had come to regard her daughter as one who had supplanted her in her husband's affections, and her husband as robbing her of the love of her daughter. In truth, Mrs. Samuel Anderson had come to stand so perpetually on guard against imaginary encroachments on her rights, that she saw enemies everywhere. She hated Wehle because he was a Dutchman; she would have hated him on a dozen other scores if he had been an American. It was offense enough that Julia loved him.

So now she resolved to gain her husband to her side by her version of the story, and before dinner she had told him how August had charged her with being false and cruel to Andrew many years ago, and how Jule had thrown it up to her, and how near she had come to dropping down with palpitation of the heart. And Samuel Anderson reddened, and declared that he would protect his wife from such insults. The notion that he protected his wife was a pleasant fiction of the little man's, which received a generous encouragement at the hands of his wife. It was a favorite trick of hers to throw herself, in a metaphorical way, at his feet, a helpless woman, and in her feebleness implore his protection. And Samuel felt all the courage of knighthood in defending his inoffensive wife. Under cover of this fiction, so flattering to the vanity of an overawed husband, she had managed at one time or another to embroil him with almost all the neighbors, and his refusal to join fences had resulted in that crooked arrangement known as a "devil's lane" on three sides of his farm.

Julia dared not stay away from dinner, which was miserable enough. She did not venture so much as to look at August, who sat opposite her, and who was the most unhappy person at the table, because he did not know what all the unhappiness was about. Mr. Anderson's brow foreboded a storm, Mrs. Anderson's face was full of an earthquake, Cynthy Ann was sitting in shadow, and Julia's countenance perplexed him. Whether she was angry with him or not, he could not be sure. Of one thing he was certain: she was suffering a great deal, and that was enough to make him exceedingly unhappy.

Sitting through his hurried meal in this atmosphere surcharged with domestic electricity, he got the notion--he could hardly tell how--that all this lowering of the sky had something to do with him. What had he done? Nothing. His closest self-examination told him that he had done no wrong. But his spirits were depressed, and his sensitive conscience condemned him for some unknown crime that had brought about all this disturbance of the elements. The ham did not seem very good, the cabbage he could not eat, the corn-dodger choked him, he had no desire to wait for the pie. He abridged his meal, and went out to the barn to keep company with his horses and his misery until it should be time to return to his plow.

Julia sat and sewed in that tedious afternoon. She would have liked one more interview with August before his departure. Looking through the open hall, she saw him leave the barn and go toward his plowing. Not that she looked up. Hawk never watched chicken more closely than Mrs. Anderson watched poor Jule. But out of the corners of her eyes Julia saw him drive his horses before him from the stable. At the field in which he worked was on the other side of the house from where she sat she could not so much as catch a glimpse of him as he held his plow on its steady course. She wished she might have helped Cynthy Ann in the kitchen, for then she could have seen him, but there was no chance for such a transfer.

Thus the tedious afternoon wore away, and just as the sun was settling down so that the shadow of the elm in the front-yard stretched across the road into the cow pasture, the dead silence was broken. Julia had been wishing that somebody would speak. Her mother's sulky speechlessness was worse than her scolding, and Julia had even wished her to resume her storming. But the silence was broken by Cynthy Ann, who came into the hall and called, "Jule, I wish you would go to the barn and gether the eggs; I want to make some cake."

Every evening of her life Julia gathered the eggs, and there was nothing uncommon in Cynthy Ann's making cake, so that nothing could be more innocent than this request. Julia sat opposite the front-door, her mother sat farther along. Julia could see the face of Cynthy Ann. Her mother could only hear the voice, which was dry and commonplace enough. Julia thought she detected something peculiar in Cynthy's manner. She would as soon have thought of the big oak gate-posts with their round ball-like heads telegraphing her in a sly way, as to have suspected any such craft on the part of Cynthy Ann, who was a good, pious, simple-hearted, Methodist old maid, strict with herself, and censorious toward others. But there stood Cynthy making some sort of gesture, which Julia took to mean that she was to go quick. She did not dare to show any eagerness. She laid down her work, and moved away listlessly. And evidently she had been too slow. For if August had been in sight when Cynthy Ann called her, he had now disappeared on the other side of the hill. She loitered along, hoping that he would come in sight, but he did not, and then she almost smiled to think how foolish she had been in imagining that Cynthy Ann had any interest in her love affair. Doubtless Cynthy sided with her mother.

And so she climbed from mow to mow gathering the eggs. No place is sweeter than a mow, no occupation can be more delightful than gathering the fresh eggs--great glorious pearls, more beautiful than any that men dive for, despised only because they are so common and so useful! But Julia, gliding about noiselessly, did not think much of the eggs, did not give much attention to the hens scratching for wheat kernels amongst the straw, nor to the barn swallows chattering over the adobe dwellings which they were building among the rafters above her. She had often listened to the love-talk of these last, but now her heart was too heavy to hear. She slid down to the edge of one of the mows, and sat there a few feet above the threshing-floor with her bonnet in her hand, looking off sadly and vacantly. It was pleasant to sit here alone and think, without the feeling that her mother was penetrating her thoughts.

A little rustle brought her to consciousness. Her face was fiery red in a minute. There, in one corner of the threshing-floor, stood August, gazing at her. He had come into the barn to find a single-tree in place of one which had broken. While he was looking for it, Julia had come, and he had stood and looked, unable to decide whether to speak or not, uncertain how deeply she might be offended, since she had never once let her eyes rest on him at dinner. And when she had come to the edge of the mow and stopped there in a reverie, August had been utterly spell-bound.

A minute she blushed. Then, perceiving her opportunity, she dropped herself to the floor and walked up to August.

"August, you are to be turned off to-morrow night."

"What have I done? Anything wrong?"

"No."

"Why do they send me away?"

"Because--because--" Julia stopped.

But silence is often better than speech. A sudden intelligence came into the blue eyes of August. "They turn me off because I love Jule Anderson."

A LITTLE RUSTLE BROUGHT HER TO CONSCIOUSNESS.

Julia blushed just a little.

"I will love her all the same when I am gone. I will always love her."

Julia did not know what to say to this passionate speech, so she contented herself with looking a little grateful and very foolish.

"But I am only a poor boy, and a Dutchman at that"--he said this bitterly--"but if you will wait, Jule, I will show them I am of some account. Not good enough for you, but good enough for them. You will--"

"I will wait--forever--for you, Gus." Her head was down, and her voice could hardly be heard. "Good-by." She stretched out her hand, and he took it trembling.

"Wait a minute." He dropped the hand, and taking a pencil wrote on a beam:

"March 18th, 1843."

"There, that's to remember the Dutchman by."

"Don't call yourself a Dutchman, August. One day in school, when I was sitting opposite to you, I learned this definition, 'August: grand, magnificent,' and I looked at you and said, Yes, that he is. August is grand and magnificent, and that's what you are. You're just grand!"

I do not think he was to blame. I am sure he was not responsible. It was done so quickly. He kissed her forehead and then her lips, and said good-by and was gone. And she, with her apron full of eggs and her cheeks very red--it makes one warm to climb--went back to the house, resolved in some way to thank Cynthy Ann for sending her; but Cynthy Ann's face was so serious and austere in its look that Julia concluded she must have been mistaken, Cynthy Ann couldn't have known that August was in the barn. For all she said was:

"You got a right smart lot of eggs, didn't you? The hens is beginnin' to lay more peart since the warm spell sot in."

"Vot you kits doornt off vor? Hey?"

Gottlieb Wehle always spoke English, or what he called English, when he was angry.

"Vot for? Hey?"

All the way home from Anderson's on that Saturday night, August had been, in imagination, listening to the rough voice of his honest father asking this question, and he had been trying to find a satisfactory answer to it. He might say that Mr. Anderson did not want to keep a hand any longer. But that would not be true. And a young man with August's clear blue eyes was not likely to lie.

"Vot vor ton't you not shpeak? Can't you virshta blain Eenglish ven you hears it? Hey? You a'n't no teef vot shteels I shposes, unt you ton't kit no troonks mit vishky? Vot you too tat you pe shamt of? Pin lazin' rount? Kon you nicht Eenglish shprachen? Oot mit id do vonst!"

"I did not do anything to be ashamed of," said August. And yet he looked ashamed.

"You tidn't pe no shamt, hey? You tidn't! Vot vor you loogs so leig a teef in der bentenshry? Vot for you sprachen not mit me ven ich sprachs der blainest zort ov Eenglish mit you? You kooms sneaggin heim Zaturtay nocht leig a tog vots kot kigt, unt's got his dail dween his leks; and ven I aks you in blain Eenglish vot's der madder, you loogs zheepish leig, und says you a'n't tun nodin. I zay you tun sompin. If you a'n't tun nodin den, vy don't you dell me vot it is dat you has tun? Hey?"

All this time August found that it was getting harder and harder to tell his father the real state of the case. But the old man, seeing that he prevailed nothing, took a cajoling tone.

"Koom, August, mine knabe, ton't shtand dare leig a vool. Vot tit Anterson zay ven he shent you avay?"

"He said that I'd been seen a-talking to his daughter, Jule Anderson."

"Vell, you nebber said no hoorm doo Shule, tid you? If I dought you said vot you zhoodn't zay doo Shule, I vood shust drash you on der shpot! Tid you gwarl mit Shule, already?"

"Quarrel with Jule! She's the last person in the world I'd think of quarreling with. She's as good as--"

"Oh! you pe in lieb mit Shule! You vool, you! Is dat all dat I raise you vor? I dells you, unt dells you, unt dells you to sprach nodin put Deutsche, unt to marry a kood Deutsche vrau vot kood sprach mit you, unt now you koes right shtraight off unt kits knee-teep in lieb mit a vool of a Yangee kirl! You doo ant pe doornt off!"

August's countenance brightened. All the way home he had felt that it was somehow an unpardonable sin to be a Dutchman. Anderson had spoken hardly to him in dismissing him, and now it was a great comfort to find that his father returned the contempt of the Yankees at its full value. All the conceit was not on the side of the Yankees. It was at least an open question which was the most disgraced, he or Julia, by their little love affair.

But more comforting still was the quiet look of his sweet-faced mother, who, moving about among her throng of children like a hen with more chickens than she can hover[1], never forgot to be patient and affectionate. If there had been a look of reproach on the face of the mother, it would have been the hardest trial of all. But there was that in her eyes--the dear Moravian mother--that gave courage to August. The mother was an outside conscience, and now as Gottlieb, who had lapsed into German for his wife's benefit, rattled on his denunciation of this Cannanitish Yankee, with whom his son was in love, the son looked every now and then into the eyes, the still German eyes of the mother, and rejoiced that he saw there no reflection of his father's rebuke. The older Wehle presently resumed his English, such as it was, as better adapted to scolding. Whether he thought to make his children love German by abusing them in English, I do not know, but it was his habit.

[1] Not until my attention was called to this word in the proof did I know that in this sense it is a provincialism. It is so used, at least in half the country, and yet neither of our American dictionaries has it.

"I dells you tese Yangees is Yangees. Dere neber voz put shust von cood vor zompin. Antrew Antershon is von. He shtaid mit us ven ve vos all zick, unt he is zhust so cood as if he was porn in Deutschland. Put all de rest is Yangees. Marry a Deutsche vrau vot's kot cood sense to ede kraut unt shleep unter vedder peds ven it's kalt. Put shust led de Yangees pe Yangees."

Seeing August put on his hat and go to the door, he called out testily:

"Vare you koes, already?"

"Over to the castle."

"Veil, das is koot. Ko doo de gassel. Antrew vlll dell you vat sorts do Yangee kirls pe!"

By the time August reached Andrew Anderson's castle it was dark. The castle was built in a hollow, looking out toward the Ohio River, a river that has this peculiarity, that it is all beautiful, from Pittsburgh to Cairo. Through the trees, on which the buds were just bursting, August looked out on the golden roadway made by the moonbeams on the river. And into the tumult of his feelings there came the sweet benediction of Nature. And what is Nature but the voice of God?

Anderson's castle was a large log building of strange construction. Everything about it had been built by the hands of Andrew, at once its lord and its architect. Evidently a whimsical fancy had pleased itself in the construction. It was an attempt to realize something of medieval form in logs. There were buttresses and antique windows, and by an ingenious transformation the chimney, usually such a disfigurement to a log-house, was made to look like a round donjon keep. But it was strangely composite, and I am afraid Mr. Ruskin would have considered it somewhat confused; for while it looked like a rude castle to those who approached it from the hills, it looked like something very different to those who approached the front, for upon that side was a portico with massive Doric columns, which were nothing more nor less than maple logs. Andrew maintained that the natural form of the trunk of a tree was the ideal and perfect form of a pillar.

To this picturesque structure, half castle, half cabin, with hints of church and temple, came August Wehle on Saturday evening. He did not go round to the portico and knock at the front-door as a stranger would have done, but in behind the donjon chimney he pulled an alarm-cord. Immediately the head of Andrew Anderson was thrust out of a Gothic hole--you could not call it a window. His uncut hair, rather darker than auburn, fell down to his waist, and his shaggy red beard lay upon his bosom. Instead of a coat he wore that unique garment of linsey-woolsey known in the West as wa'mus (warm us?), a sort of over-shirt. He was forty-five, but there were streaks of gray in his hair and board, and he looked older by ten years.

"What ho, good friend? Is that you?" he cried. "Come up, and right welcome!" For his language was as archaic and perhaps as incongruous as his architecture. And then throwing out of the window a rope-ladder, he called out again, "Ascend! ascend! my brave young friend!"

And young Wehle climbed up the ladder into the large upper room. For it was one peculiarity of the castle that the upper part had no visible communication with the lower. Except August, and now and then a literary stranger, no one but the owner was ever admitted to the upper story of the house, and the neighbors, who always had access to the lower rooms, regarded the upper part of the castle with mysterious awe. August was often plied with questions about it, but he always answered simply that he didn't think Mr. Anderson would like to have it talked about. For the owner there must have been some inside mode of access to the second story, but he did not choose to let even August know of any other way than that by the rope-ladder, and the few strangers who came to see his books were taken in by the same drawbridge.

The room was filled with books arranged after whimsical associations. One set of cases, for instance, was called the Academy, and into these he only admitted the masters, following the guidance of his own eccentric judgment quite as much as he followed traditional estimate. Homer, Virgil, Dante, and Milton of course had undisputed possession of the department devoted to the "Kings of Epic," as he styled them. Sophocles, Calderon, Corneille, and Shakespeare were all that he admitted to his list of "Kings of Tragedy." Lope he rejected on literary grounds, and Goethe because he thought his moral tendency bad. He rejected Rabelais from his chief humorists, but accepted Cervantes, Le Sage, Molière, Swift, Hood, and the then fresh Pickwick of Boz. To these he added the Georgia Scenes of Mr. Longstreet, insisting that they were quite equal to Don Quixote. I can only stop to mention one other department in his Academy. One case was devoted to the "Best Stories," and an admirable set they were! I wish that anything of mine were worthy to go into such company. His purity of feeling, almost ascetic, led him to reject Boccaccio, but he admitted Chaucer and some of Balzac's, and Smollett, Goldsmith, and De Foe, and Walter Scott's best, Irving's Rip Van Winkle, Bernardin St. Pierre's "Paul and Virginia," and "Three Months under the Snow," and Charles Lamb's generally overlooked "Rosamund Gray." There were eases for "Socrates and his Friends," and for other classes. He had amused himself for years in deciding what books should be "crowned," as he called it, and what not. And then he had another case, called "The Inferno." I wish there was space to give a list of this department. Some were damned for dullness and some for coarseness. Miss Edgeworth's Moral Tales, Darwin's Botanic Garden, Rollin's Ancient History, and a hideously illustrated copy of the Book of Martyrs were in the First-class, Don Juan and some French novels in the second. Tupper, Swinburne, and Walt Whitman he did not know.

In the corner next the donjon chimney was a little room with a small fireplace. Thus the hermit economized wood, for wood meant time, and time meant communion with his books. All of his domestic arrangements were carried on after this frugal fashion. In the little room was a writing-desk, covered with manuscripts and commonplace books.

"Well, my young friend, you're thrice welcome," said Andrew, who never dropped his book language. "What will you have? Will you resume your apprenticeship under Goethe, or shall we canter to Canterbury with Chaucer? Grand old Dan Chaucer! Or, shall we study magical philosophy with Roger Bacon--the Friar, the Admirable Doctor? or read good Sir Thomas More? What would Sir Thomas have said if he could have thought that he would be admired by two such people as you and I, in the woods of America, in the nineteenth century? But you do not want books! Ah! my brave friend, you are not well. Come into my cell and let us talk. What grieves you?"

And Andrew took him by the hand with the courtesy of a knight, with the tenderness of a woman, and with the air of an astrologer, and led him into the apartment of a monk.

"See!" he said, "I have made a new chair. It is the highest evidence of my love for my Teutonic friend. You have now a right to this castle. You shall be perpetually welcome. I said to myself, German scholarship shall sit there, and the Backwoods Philosopher will sit here. So sit down on my sedilium, and let us hear how this uncivil and inconstant world treats you. It can not deal worse with you than it has with me. But I have had my revenge on it! I have been revenged! I have done as I pleased, and defied the world and all its hollow conventionalities." These last words were spoken in a tone of misanthropic bitterness common to Andrew. His love for August was the more intense that it stood upon a background of general dislike, if not for the world, at least for that portion of it which most immediately surrounded him.

August took the chair, ingeniously woven and built of rye straw and hickory splints. He knew that all this formality and apparent pedantry was superficial. He and Andrew were bosom friends, and as he had often opened his heart to the master of the castle before, so now he had no difficulty in telling him his troubles, scarcely heeding the appropriate quotations which Andrew made from time to time by way of embellishment.

One reason for Andrew's love of August Wehle was that he was a German. Far from sharing in the prejudices of his neighbors against foreigners, Andrew had so thorough a contempt for his neighbors, that he liked anybody who did not belong to his own people. If a Turk had emigrated to Clark township, Andrew would have fallen in love with him, and built a divan for his special accommodation. But he loved August also for the sake of his gentle temper and his genuine love for books. And only August or August's mother, upon whom Andrew sometimes called, could exorcise his demon of misanthropy, which he had nursed so long that it was now hard to dismiss it.

Andrew Anderson belonged to a class noticed, I doubt not, by every acute observer of provincial life in this country. In backwoods and out-of-the-way communities literary culture produces marked eccentricities in the life. Your bookish man at the West has never learned to mark the distinction between the world of ideas and the world of practical life. Instead of writing poems or romances, he falls to living them, or at least trying to. Add a disappointment in love, and you will surely throw him into the class of which Anderson was the representative. For the education one gets from books is sadly one-sided, unless it be balanced by a knowledge of the world.

Andrew Anderson had always been regarded as an oddity. A man with a good share of ideality and literary taste, placed against the dull background of the society of a Western neighborhood in the former half of the century, would necessarily appear odd. Had he drifted into communities of more culture, his eccentricity, begotten of a sense of superiority to his surroundings, would have worn away. Had he been happily married, his oddities would have been softened; but neither of these things happened. He told August a very different history. For the confidence of his "Teutonic friend" had awakened in the solitary man a desire to uncover that story which he had kept under lock and key for so many years.

"Ah! my friend," said he with excitement, "don't trust the faith of a woman." And then rising from his seat he said, "The Backwoods Philosopher warns you. I pray you give good heed. I do not know Julia. She is my niece. It ill becomes me to doubt her sincerity. But I know whose daughter she is. I pray you give good heed, my Teutonic friend. I know whose daughter she is!

"I do not talk much. But you have arrived at a critical point--a point of turning. Out of his own life, out of his own sorrow, the Backwoods Philosopher warns you. I am at peace now. But look at me. Do you not see the marks of the ravages of a great storm? A sort of a qualified happiness I have in philosophy. But what I might have been if the storm had not torn me to pieces in my youth--what I might have been, that I am not. I pray you never trust in a woman's keeping the happiness of your life!"

Here Andrew slipped his arm through Wehle's, and began to promenade with him in the large apartment up and down an alley, dimly lighted by a candle, between solid phalanxes of books.

"I pray you give good heed," he said, resuming. "I was always eccentric. People thought I was either a genius or fool. Perhaps I was much of both. But this is a digression. I did not pay any attention to women. I shunned them. I said that to be a great author and a philosophical thinker, one must not be a man of society. I never went to a wood-chopping, to an apple-peeling, to a corn-shucking, to a barn-raising, nor indeed to any of our rustic feasts. I suppose this piqued the vanity of the girls, and they set themselves to catch me. I suppose they thought that I would be a trophy worth boasting. I have noticed that hunters estimate game according to the difficulty of getting it. But this is a digression. Let us return.

"There came among us, at that time, Abigail Norman. She was pretty. I swear by all the sacred cats of Egypt, that she was beautiful. She was industrious. The best housekeeper in the state! She was high-strung. I liked her all the more for that. You see a man of imagination is apt to fall in love with a tragedy queen. But this is a digression. Let us return.

"She spread her toils in my path. While I was wandering through the woods writing poetry to birds and squirrels, Abby Norman was ambitious enough to hope to make me her slave, and she did. She read books that she thought I liked. She planned in various ways to seem to like what I liked, and yet she had sense enough to differ a little from me, and so make herself the more interesting. I think a man of real intellect never likes to have a man or woman agree with him entirely. But let us return.

"I loved Abigail desperately. No, I did not love Abigail Norman at all. I did not love her as she was, but I loved her as she seemed to my imagination to be. I think most lovers love an ideal that hovers in the air a little above the real recipient of their love. And I think we men of genius and imagination are apt to love something very different from the real person, which is unfortunate.

"But I am digressing again. To return: I wrote poetry to Abby. I courted her. I cut off my long hair for a woman, like Samson. I tried to dress more decently, and made myself ridiculous no doubt, for a man can not dress well unless he has a talent for it. And I never had a genius for beau-knots.

"But pardon the digression. Let us return. I was to have married her. The day was set. Then I found accidentally that she was engaged to my brother Samuel, a young man with better manners than mind. She made him believe that she was only making a butt of me. But I think she really loved me more than she knew. When I had discovered her treachery, I shipped on the first flat-boat. I came near committing suicide, and should have jumped into the river one night, only that I thought it might flatter her vanity. I came back here and ignored her. She broke with Samuel and tried to regain my affections. I scorned her. I trod on her heart! I stamped her pride into the dust! I was cruel. I was contemptuous. I was well-nigh insane. Then she went back to Samuel, and made him marry her. Then she forced my imbecile old father, on his death-bed, to will all the property to Samuel, except this piece of rough hill-land and one thousand dollars. But here I built this castle. My thousand dollars I put in books. I learned how, to weave the coverlets of which our country people are so fond, and by this means, and by selling wood to the steamboats, I have made a living and bought my library without having to work half of my time. I was determined never to leave. I swore by all the arms of Vishnu she should never say that she had driven me away. I don't know anything about Julia. But I know whose daughter she is. My young friend, beware! I pray you take good heed! The Backwoods Philosopher warns you!"

If the gentleman is not born in a man, it can not be bred in him. If it is born in him, it can not be bred out of him. August Wehle had inherited from his mother the instinct of true gentlemanliness. And now, when Andrew relapsed into silence and abstraction, he did not attempt to rouse him, but bidding him goodnight, with his own hands threw the rope-ladder out the window and started up the hollow toward home. The air was sultry and oppressive, the moon had been engulfed, and the first thunder-cloud of the spring was pushing itself up toward the zenith, while the boughs of the trees were quivering with a premonitory shudder. But August did not hasten. The real storm was within. Andrew's story had raised doubts. When he went down the ravine the love of Julia Anderson shone upon his heart as benignly as the moon upon the waters. Now the light was gone, and the black cloud of a doubt had shut out his peace. Jule Anderson's father was rich. He had not thought of it before! But now he remembered how much woodland he owned and how he had two large farms. Jule Anderson would not marry a poor boy. And a Dutchman! She was not sincere. She was trifling with him and teasing her parents. Or, if she were sincere now, she would not be faithful to him against every tempting offer. And he would have to drive on the rocks, too, as Andrew had. At any rate, he would not marry her until he stood upon some sort of equality with her.

The wind was swaying him about in its fitful gusts, and he rather liked it. In his anguish of spirit it was a pleasure to contend with the storm. The wind, the lightning, the sudden sharp claps of thunder were on his own key. He felt in the temper of old Lear. The winds might blow and crack their cheeks.

But it was not alone the suggestions of Andrew that aroused his suspicions. He now recalled a strange statement that Samuel Anderson made in discharging him. "You said what you had no right to say about my wife, in talking to Julia." What had he said? Only that some woman had not treated Andrew "just right." Who the woman might be he had not known until his present interview with Andrew. Had Julia been making mischief herself by repeating his words and giving them a direction he had not intended? He could not have dreamed of her acting such a part but for the strange influence of Andrew's strange story. And so he staggered on, wet to the skin, defying in his heart the lightning and the wind, until he came to the cabin of his father. Climbing the fence, for there was no gate, he pulled the latch-string and entered. They were all asleep; the hard-working family went to bed early. But chubby-faced Wilhelmina, the favorite sister, had set up to wait for August, and he now found her fast asleep in the chair.

"Wilhelmina! wake up!" he said.

"O August!" she said, opening the corner of one eye and yawning, "I wasn't asleep. I only--uh--shut my eyes a minute. How wet you are! Did you go to see the pretty girl up at Mr. Anderson's?"

"No," said August.

"O August! she is pretty, and she is good and sweet," and Wilhelmina took his wet checks between her chubby hands and gave him a sleepy kiss, and then crept off to bed.

And, somehow, the faith of the child Wilhelmina counteracted the skepticism of the and Andrew, and August felt the storm subsiding.

When he looked out of the window of the loft in which he slept the shower had ceased as suddenly as it had come, the thunder had retreated behind the hills, the clouds were already breaking, and the white face of the moon was peering through the ragged rifts.

"Figgers won't lie," said Elder Hankins, the Millerite preacher. "I say figgers won't lie. When a Methodis' talks about fallin' from grace he has to argy the pint. And argyments can't be depended 'pon. And when a Prisbyterian talks about parseverance he haint got the absolute sartainty on his side. But figgers won't lie noways, and it's figgers that shows this yer to be the last yer of the world, and that the final eend of all things is approachin'. I don't ask you to listen to no 'mpressions of me own, to no reasonin' of nobody; all I ask is that you should listen to the voice of the man in the linen-coat what spoke to Dan'el, and then listen to the voice of the 'rithmetic, and to a sum in simple addition, the simplest sort of addition."

All the Millerite preachers of that day were not quite so illiterate as Elder Hankins, and it is but fair to say that the Adventists of to-day are a very respectable denomination, doing a work which deserves more recognition from others than it receives. And for the delusion which expects the world to come to an end immediately, the Adventist leaders are not responsible in the first place. From Gnosticism to Mormonism, every religious delusion has grown from some fundamental error in the previous religious teaching of the people. By the narrowly verbal method of reading the Scripture, so much in vogue in the polemical discussions of the past generation, and still so fervently adhered to by many people, the ground was prepared for Millerism. And to-day in many regions the soil in made fallow for the next fanaticism. It is only a question of who shall first sow and reap. To people educated as those who gathered in Sugar Grove school-house had been to destroy the spirit of the Scripture by distorting the letter in proving their own sect right, nothing could be so overwhelming as Elder Hankins's "figgers."

For he had clearly studied figgers to the neglect of the other branches of a liberal education. His demonstration was printed on a large chart. He began with the seventy weeks of Daniel, he added in the "time and times and a half," and what Daniel declared that he "understood not when he heard," was plain sailing to the enlightened and mathematical mind of Elder Hankins. When he came to the thousand two hundred and ninety days, he waxed more exultant than Kepler in his supreme moment, and on the thousand three hundred and five and thirty days he did what Jonas Harrison called "the blamedest tallest cipherin' he'd ever seed in all his born days."

Jonas was the new hired man, who had stopped into the shoes of August at Samuel Anderson's. He sat by August and kept up a running commentary, in a loud whisper, on the sermon, "My feller-citizen," said Jonas, squeezing August's arm at a climax of the elder's discourse, "My feller-citizen, looky thar, won't you? He'll cipher the world into nothin' in no time. He's like the feller that tried to find out the valoo of a fat shoat when wood was two dollars a cord. 'Ef I can't do it by substraction I'll do it by long-division,' says he. And ef this 'rithmetic preacher can't make a finishment of this sublunary speer by addition, he'll do it by multiplyin'. They's only one answer in his book. Gin him any sum you please, and it all comes out 1843!"

Now in all the region round about Sugar Grove school-house there was a great dearth of sensation. The people liked the prospect of the end of the world because it would be a spectacle, something to relieve the fearful monotony of their lives. Funerals and weddings were commonplace, and nothing could have been so interesting to them as the coming of the end of the world, as described by Elder Hankins, unless it had been a first-class circus (with two camels and a cage of monkeys attached, so that scrupulous people might attend from a laudable desire to see the menagerie!) A murder would have been delightful to the people of Clark township. It would have given them something to think and talk about. Into this still pool Elder Hankins threw the vials, the trumpets, the thunders, the beast with ten horns, the he-goat, and all the other apocalyptic symbols understood in an absurdly literal way. The world was to come to an end in the following August. Here was an excitement, something worth living for.

All the way to their homes the people disputed learnedly about the "time and times and a half," about "the seven heads and ten horns," and the seventh vial. The fierce polemical discussions and the bold sectarian dogmatism of the day had taught them anything but "the modesty of true science," and now the unsolvable problems of the centuries were taken out of the hands of puzzled scholars and settled as summarily and positively as the relative merits of "gourd-seed" and "flint" corn. Samuel Anderson had always planted his corn in the "light" of the moon and his potatoes in the "dark" of that orb, had always killed his hogs when the moon was on the increase lest the meat should all go to gravy, and he and his wife had carefully guarded against the carrying of a hoe through the house, for fear "somebody might die." Now, the preaching of the elder impressed him powerfully. His life had always been not so much a bad one as a cowardly one, and to get into heaven by a six months' repentance, seemed to him a good transaction. Besides he remembered that there men were never married, and that there, at last, Abigail would no longer have any peculiar right to torture him. Hankins could not have ciphered him into Millerism if his wife had not driven him into it as the easiest means of getting a divorce. No doom in the next world could have alarmed him much, unless it had been the prospect of continuing lord and master of Mrs. Abigail. And as for that oppressed woman, she was simply scared. She was quite unwilling to admit the coming of the world's end so soon. Having some ugly accounts to settle, she would fain have postponed the payday. Mrs. Anderson might truly have been called a woman who feared God--she had reason to.

And as for August, he would not have cared much if the world had come to an end, if only he could have secured one glance of recognition from the eyes of Julia. But Julia dared not look. The process of cowing her had gone on from childhood, and now she was under a reign of terror. She did not yet know that she could resist her mother. And then she lived in mortal fear of her mother's heart-disease. By irritating her she might kill her. This dread of matricide her mother held always over her. In vain she watched for a chance. It did not come. Once, when her mother's head was turned, she glanced at August. But he was at that moment listening or trying to listen to one of Jonas Harrison's remarks. And August, who did not understand the circumstances, was only able to account for her apparent coldness on the theory suggested by Andrew's universal unbelief in women, or by supposing that when she understood his innocent remark about Andrew's disappointment to refer to her mother, she had taken offense at it. And so, while the rest were debating whether the world would come to an end or not, August had a disconsolate feeling that the end of the world had already come. And it did not make him feel better to have Wilhelmina whisper, "Oh! but she is pretty, that Anderson girl--a'n't she, August?"

"He sings like an owlingale!"

Jonas Harrison was leaning against the well-curb, talking to Cynthy Ann. He'd been down to the store at Brayville, he said, a listenin' to 'em discuss Millerism, and seed a new singing-master there. "Could he sing good?" Cynthy asked, rather to prolong the talk than to get information.

"Sings like an owlingale, I reckon. He's got more seals to his ministry a-hanging onto his watch-chain than I ever seed. Got a mustache onto the top story of his mouth, somethin' like a tuft of grass on the roof of a ole shed kitchen. Peart? He's the peartest-lookin' chap I ever seed. But he a'n't no singin'-master--not of I'm any jedge of turnips. He warn't born to sarve his day and generation with a tunin'-fork. I think he's a-goin' to reckon-water a little in these parts and that he's only a-playin' singin'-master. He kin play more fiddles'n one, you bet a hoss! Says he come up here fer his wholesome, and I guess he did. Think ef he'd a-staid where he was, he mout a-suffered a leetle from confinement to his room, and that room p'raps not more nor five foot by nine, and ruther dim-lighted and poor-provisioned, an' not much chance fer takin' exercise in the fresh air!"

"DON'T BE ONCHARITABLE, JONAS."

"Don't be oncharitable, Jonas, don't. We're all mis'able sinners, I s'pose; and you know charity don't think no evil. The man may be all right, ef he does wear hair on his lip. Charity kivers lots a sins."

"Ya-as, but charity don't kiver no wolves with wool. An' ef he a'n't a woolly wolf they's no snakes in Jarsey, as little Ridin' Hood said when her granny tried to bite her head off. I'm dead sot in favor of charity, and mean to gin her my vote at every election, but I a'n't a-goin' to have her put a blind-bridle on to me. And when a man comes to Clark township a-wearing straps to his breechaloons to keep hisself from leaving terry-firmy altogether, and a weightin' hisself down with pewter watch-seals, gold-washed, and a cultivating a crap of red-top hay onto his upper lip, and a-lettin' on to be a singin'-master, I suspicions him. They's too much in the git-up fer the come-out. Well, here's yer health, Cynthy!"

And having made this oracular speech and quaffed the hard limestone water, Jonas hung the clean white gourd from which he had been drinking, in its place against the well-curb, and started back to the field, while Cynthy Ann carried her bucket of water into the kitchen, blaming herself for standing so long talking to Jonas. To Cynthy everything pleasant had a flavor of sinfulness.

The pail of water was hardly set down in the sink when there came a knock at the door, and Cynthy found standing by it the strapped pantaloons, the "red-top" mustache, the watch-seals, and all the rest that went to make up the new singing-master. He smiled when he saw her, one of those smiles which are strictly limited to the lower half of the face, and are wholly mechanical, as though certain strings inside were pulled with malice aforethought and the mouth jerked out into a square grin, such as an ingeniously-made automaton might display.

"Is Mr. Anderson in?"

"No, sir; he's gone to town."

"Is Mrs. Anderson in?"

And so he entered, and soon got into conversation with the lady of the house, and despite the prejudice which she entertained for mustaches, she soon came to like him. He smiled so artistically. He talked so fluently. He humored all her whims, pitied all her complaints, and staid to dinner, eating her best preserves with a graciousness that made Mrs. Anderson feel how great was his condescension. For Mr. Humphreys, the singing-master, had looked at the comely face of Julia, and looked over Julia's shoulders at the broad acres beyond; and he thought that in Clark township he had not met with so fine a landscape, so nice a figure-piece. And with the quick eye of a man of the world, he had measured Mrs. Anderson, and calculated on the ease with which he might complete the picture to suit his taste.

He staid to supper. He smiled that same fascinating square smile on Samuel Anderson, treated him as head of the house, talked glibly of farming, and listened better than he talked. He gave no account of himself, except by way of allusion. He would begin a sentence thus, "When I was traveling in France with my poor dear mother," etc., from which Mrs. Anderson gathered that he had been a devoted son, and then he would relate how he had seen something curious "when he was dining at the house of the American minister at Berlin." "This hazy air reminds me of my native mountains in Northern New York." And then he would allude to his study of music in the Conservatory in Leipsic. To plain country people in an out-of-the-way Western neighborhood, in 1843, such a man was better than a lyceum full of lectures. He brought them the odor of foreign travel, the flavor of city, the "otherness" that everybody craves.

He staid to dinner, as I have said, and to supper. He staid over night. He took up his board at the house of Samuel Anderson. Who could resist his entreaty? Did he not assure them that he felt the need of a home in a cultivated family? And was it not the one golden opportunity to have the daughter of the house taught music by a private master, and thus give a special eclat to her education? How Mrs. Anderson hoped that this superior advantage would provoke jealous remarks on the part of her neighbors! It was only necessary to the completion of her triumph that they should say she was "stuck up." Then, too, to have so brilliant a beau for Julia! A beau with watch-seals and a mustache, a beau who had been to Paris with his mother, studied music in the Conservatory at Leipsic, dined with the American minister in Berlin, and done ever so many more wonderful things, was a prospect to delight the ambitious heart of Mrs. Anderson, especially as he flattered the mother instead of the daughter.

"He's a independent citizen of this Federal Union," said Jonas to Cynthy, "carries his head like he was intimately 'quainted with the 'merican eagle hisself. He's playin' this game sharp. He deals all the trumps to hisself, and most everything besides. He'll carry off the gal if something don't arrest him in his headlong career. Jist let me git a chance at him when he's soarin' loftiest into the amber blue above, and I'll cut his kite-string for him, and let him fall like fork-ed lightnin' into a mud-puddle."

Cynthy said she did see one great sin that he had committed for sure. That was the puttin' on of gold and costly apparel. It was sot down in the Bible and in the Methodist Discipline that it was a sin to wear gold, and she should think the poor man hadn't no sort o' regard for his soul, weighing it down with them things.

But Jonas only remarked that he guessed his jewelry warn't no sin. He didn't remember nothing agin wearin' pewter.

The singing-master, Mr. Humphreys, went to singing-school and church with Julia in a matter-of-course way, treating her with attention, but taking care not to make himself too attentive. Except that Julia could not endure his smile--which was, like some joint stock companies, strictly limited--she liked him well enough. It was something to her, in her monotonous life under the eye of her mother, who almost never left her alone, and who cut off all chance for communication with August--it was something to have the unobtrusive attentions of Mr. Humphreys, who always interested her with his adventures. For indeed it really seemed that he had had more adventures than any dozen other men. How should a simple-hearted girl understand him? How should she read the riddle of a life so full of duplicity--of multiplicity--as the life of Joshua Humphreys, the music-teacher? Humphreys intended to make love to her, but during the first two weeks he only aimed to gain her esteem. He felt that there was a clue which he had not got. But at last the key dropped into his hands, and he felt sure that the unsophisticated girl was in his power.

Among the girls that attended Humphreys's singing-school was Betsey Malcolm, the near neighbor of the Andersons. The singing-master often saw her at Mr. Anderson's, and he often wished that Julia were as easy to win as he felt Betsey to be. The sensuous mouth, the giddy eyes of Betsey, showed quickly her appreciation of every flattering attention he paid her, and though in Julia's presence he was careful how he treated her, yet when he, walking down the road one day, alone, met her, he courted her assiduously. He had not to observe any caution in her case. She greedily absorbed all the flattery he could give, only pettishly responding after a while: "O dear! that's the way you talk to me, and that's the way you talk to Jule sometimes, I s'pose. I guess she don't mind keeping two of you as strings to her bow."

"Two! What do you mean, my fair friend? I havn't seen one, yet."

"Oh, no! You mean you haven't seen two. You see one whenever you look in the glass. The other is a Dutchman, and she's dying after him. She may flirt with you, but her mother watches her night and day, to keep her from running off with Gus Wehle."

Like many another crafty person, Betsey Malcolm had fairly overshot the mark. In seeking to separate Humphreys from Julia, she had given him the clue he desired, and he was not slow to use it, for he was almost the only person that Mrs. Anderson trusted alone with Julia.

In the dusk of the evening of the very day of his talk with Betsey, he sat on the long front-porch with Julia. Julia liked him better, or rather did not dislike him so much in the dark as she did in the light. For when it was light she could see him smile, and though she had not learned to connect a cold-blooded face with a villainous character, she had that childish instinct which made her shrink from Humphreys's square smile. It always seemed to her that the real Humphreys gazed at her out of the cold, glittering eyes, and that the smile was something with which he had nothing to do.

Sitting thus in the dusk of the evening, and looking out over the green pasture to where the nigher hills ceased and the distant seemed to come immediately after, their distance only indicated by color, though the whole Ohio "bottom" was between, she forgot the Mephistopheles who sat not far away, and dreamed of August, the "grand," as she fancifully called him. And he let her sit and dream undisturbed for a long time, until the darkness settled down upon the hills. Then he spoke.

"I--I thought," began Humphreys, with well-feigned hesitancy, "I thought, I should venture to offer you my assistance as a true and gallant man, in a matter--a matter of supreme delicacy--a matter that I have no right to meddle with. I think I have heard that your mother is not friendly to the suit of a young man who--who--well, let us say who is not wholly disagreeable to you. I beg your pardon, don't tell me anything that you prefer to keep locked in the privacy of your own bosom. But if I can render any assistance, you know. I have some little influence with your parents, maybe. If I could be the happy bearer of any communications, command me as your obedient servant."

Julia did not know what to say. To get a word to August was what she most desired. But the thought of using Humphreys was repulsive to her. She could not see his face in the gathering darkness, but she could feel him smile that same soulless, geometrical smile. She could not do it. She did not know what to say. So she said nothing. Humphreys saw that he must begin farther back.

"I hear the young man spoken of as a praiseworthy person. German, I believe? I have always noticed a peculiar manliness about Germans. A peculiar refinement, indeed, and a courtesy that is often wanting in Americans. I noticed this when I was in Leipsic. I don't think the German girls are quite so refined. German gentlemen in this country seem to prefer American girls oftentimes."

All this might have sounded hollow enough to a disinterested listener. To Julia the words were as sweet as the first rain after a tedious drouth. She had heard complaint, censure, innuendo, and downright abuse of poor Gus. These were the first generous words. They confirmed her judgment, they comforted her heart, they made her feel grateful, even affectionate toward the fop, in spite of his watch-seals, his curled mustache, his straps, his cold eyes, and his artificial smile. Poor fool you will call her, and poor fool she was. For she could have thrown herself at the feet of Humphreys, and thanked him for his words. Thank him she did in a stammering way, and he did not hesitate to repeat his favorable impressions of Germans, after that. What he wanted was, not to break the hold of August until he had placed himself in a position to be next heir to her regard.