The Project Gutenberg eBook, Study of Child Life, by Marion Foster

Washburne

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Study of Child Life

Author: Marion Foster Washburne

Release Date: September 15, 2004 [eBook #13467]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STUDY OF CHILD LIFE***

E-text prepared by Stan Goodman, Leah Moser,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

THE LIBRARY

OF

HOME ECONOMICS

A COMPLETE HOME-STUDY COURSE

ON THE NEW PROFESSION OF HOME-MAKING AND ART OF RIGHT LIVING;

THE PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE MOST RECENT ADVANCES

IN THE ARTS AND SCIENCES TO HOME AND HEALTH

PREPARED BY TEACHERS OF

RECOGNIZED AUTHORITY

FOR HOME-MAKERS, MOTHERS, TEACHERS, PHYSICIANS, NURSES, DIETITIANS,

PROFESSIONAL HOUSE MANAGERS, AND ALL INTERESTED

IN HOME, HEALTH, ECONOMY AND CHILDREN

TWELVE VOLUMES

NEARLY THREE THOUSAND PAGES, ONE THOUSAND ILLUSTRATIONS

TESTED BY USE IN CORRESPONDENCE INSTRUCTION

REVISED AND SUPPLEMENTED

CHICAGO

AMERICAN SCHOOL OF HOME ECONOMICS

1907

AUTHORS

ISABEL BEVIER, Ph.M.

Professor of Household Science, University of Illinois.

Author U.S. Government Bulletins, "Development of the Home Economics Movement

in America," etc.

ALICE PELOUBET NORTON, M.A.

Assistant Professor of Home Economics, School of

Education, University of Chicago; Director of the Chautauqua School of Domestic

Science.

S. MARIA ELLIOTT

Instructor in Home Economics, Simmons College; Formerly

Instructor School of Housekeeping, Boston.

ANNA BARROWS

Director Chautauqua School of Cookery; Lecturer Teachers'

College, Columbia University, and Simmons College; formerly Editor "American

Kitchen Magazine;" Author "Home Science Cook Book."

ALFRED CLEVELAND COTTON, A.M., M.D.

Professor Diseases of Children, Rush Medical College,

University of Chicago; Visiting Physician Presbyterian Hospital, Chicago;

Author of "Diseases of Children."

BERTHA M. TERRILL, A.B.

Professor in Home Economics in Hartford School of

Pedagogy; Author of U.S. Government Bulletins.

KATE HEINTZ WATSON

Formerly Instructor in Domestic Economy, Lewis Institute;

Lecturer University of Chicago.

MARION FOSTER WASHBURNE

Editor "The Mothers' Magazine;" Lecturer Chicago Froebel

Association; Author "Everyday Essays", "Family Secrets," etc.

MARGARET E. DODD

Graduate Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Teacher of

Science, Woodward Institute.

AMY ELIZABETH POPE

With the Panama Canal Commission; Formerly Instructor in

Practical and Theoretical Nursing, Training School for Nurses, Presbyterian

Hospital, New York City.

MAURICE LE BOSQUET, S.B.

Director American School of Home Economics; Member

American Public Health Association and American Chemical Society.

CONTRIBUTORS AND EDITORS

ELLEN H. RICHARDS

Author "Cost of Food," "Cost of Living," "Cost of

Shelter," "Food Materials and Their Adulteration," etc., etc.; Chairman Lake

Placid Conference on Home Economics.

MARY HINMAN ABEL

Author of U.S. Government Bulletins, "Practical Sanitary

and Economic Cooking," "Safe Food," etc.

THOMAS D. WOOD, M.D.

Professor of Physical Education, Columbia

University.

H.M. LUFKIN, M.D.

Professor of Physical Diagnosis and Clinical Medicine,

University of Minnesota.

OTTO FOLIN, Ph.D.

Special Investigator, McLean Hospital, Waverly,

Mass.

T. MITCHELL PRUDDEN, M.D., LL.D.

Author "Dust and Its Dangers," "The Story of the

Bacteria," "Drinking Water and Ice Supplies," etc.

FRANK CHOUTEAU BROWN

Architect, Boston, Mass.; Author of "The Five Orders of

Architecture," "Letters and Lettering."

MRS. MELVIL DEWEY

Secretary Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics.

HELEN LOUISE JOHNSON

Professor of Home Economics, James Millikan University,

Decatur.

FRANK W. ALLEN, M.D.

Instructor Rush Medical College, University of

Chicago.

MANAGING EDITOR

MAURICE LE BOSQUET, S.B.

Director American School of Home Economics.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

OF THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF HOME ECONOMICS

MRS. ARTHUR COURTENAY NEVILLE

President of the Board.

MISS MARIA PARLOA

Founder of the first Cooking School in Boston; Author of

"Home Economics," "Young Housekeeper," U.S. Government Bulletins, etc.

MRS. MARY HINMAN ABEL

Co-worker in the "New England Kitchen," and the "Rumford

Food Laboratory;" Author of U.S. Government Bulletins, "Practical Sanitary and

Economic Cooking," etc.

MISS ALICE RAVENHILL

Special Commissioner sent by the British Government to

report on the Schools of Home Economics in the United States; Fellow of the

Royal Sanitary Institute, London.

MRS. ELLEN M. HENROTIN

Honorary President General Federation of Woman's

Clubs.

MRS. FREDERIC W. SCHOFF

President National Congress of Mothers.

MRS. LINDA HULL LARNED

Past President National Household Economics Association;

Author of "Hostess of To-day."

MRS. WALTER McNAB MILLER

Chairman of the Pure Food Committee of the General

Federation of Woman's Clubs.

MRS. J.A. KIMBERLY

Vice President of the National Household Economics

Association.

MRS. JOHN HOODLESS

Government Superintendent of Domestic Science for the

province of Ontario; Founder Ontario Normal School of Domestic Science, now the

MacDonald Institute.

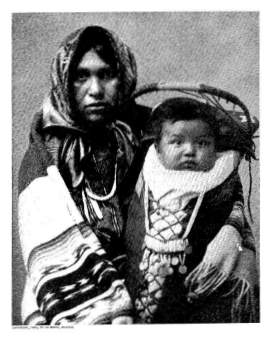

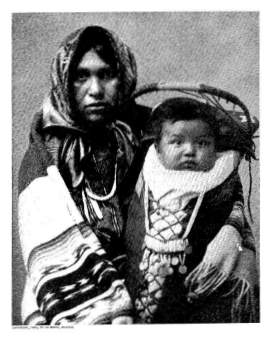

A MADONNA OF THE WILD.

A MADONNA OF THE WILD.

A Takima mother with papoose

STUDY OF CHILD LIFE

BY

MARION FOSTER WASHBURNE

ASSOCIATE EDITOR MOTHER'S MAGAZINE

AUTHOR "EVERYDAY ESSAYS"

"FAMILY SECRETS" ETC.

LECTURER TO CHICAGO FROEBEL ASSOCIATION

CHICAGO

AMERICAN SCHOOL OF HOME ECONOMICS

1907

CONTENTS

AN OPEN LETTER

DEVELOPMENT OF THE CHILD

FAULTS AND THEIR REMEDIES

CHARACTER BUILDING

PLAY

OCCUPATIONS

ART AND LITERATURE IN CHILD LIFE

STUDIES AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS

FINANCIAL TRAINING

RELIGIOUS TRAINING

APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES

OTHER PEOPLE'S CHILDREN

THE SEX QUESTION

FATHERS

THE UNCONSCIOUS INFLUENCE

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUPPLEMENTAL STUDY PROGRAM

INDEX

AMERICAN SCHOOL OF HOME ECONOMICS

CHICAGO

January 1, 1907.

My dear Madam:

In beginning this subject of the "Study of Child Life" there may

be lurking doubts in your mind as to whether any reliable rules can

really be laid down. They seem to arise mostly from the perception of

the great difference between children. What will do for one child will

not do for another. Some children are easily persuaded and gentle,

others willful, still others sullen unresponsive. How, then, is

it possible that a system of education and training can be devised

suitable for their various dispositions?

We must remember that children are much more alike than they are

different. One may have blue eyes, another gray, another black, but

they all have two. We are, therefore, in a position to make rules for

creatures having two eyes and these rules apply to eyes of all colors.

Children may be nervous, sanguine, bilious, or plethoric, but they all

have the same kind of internal organs end the same general rules of

health apply to them all.

In this series of lessons I have endeavored to set forth principles

briefly and to confirm them by instances within the experience of

every observer of childhood. The rules given are such as are held at

present by the best educators to be based upon sound philosophy, not

at variance with the slight array or scientific facts at our command.

Perhaps you yourself may be able to add to the number of reliable

facts intelligently reported that must be collected before much

greater scientific advance is possible.

There is, to be sure, an art of application of these rules both in

matters of health of body and of health of mind and this art must be

worked out by each mother for each individual child.

We all recognize that it is a long endeavor before we can apply to our

own lives such principles of conduct as we heartily acknowledge to be

right. Why, then, expect to be able to apply principles instantly

and unerringly to a little child? If a rule fails when you attempt

to apply it, before questioning the principle, may it not be well to

question your own tact and skill?

So far as I can advise with you in special instances of difficulty, I

shall be very glad to do so; not that I shall always know what to do

myself, but that we can get a little more light upon the problems by

conferring together. I know well how difficult a matter this of child

training is, for every day, in the management of my own family of

children, I find each philosophy, science and art as I can command

very much put to the test.

Sincerely yours,

Instructor

STUDY OF CHILD LIFE

PART I.

The young of the human species is less able to care for itself than the

young of any other species. Most other creatures are able to walk, or at any

rate stand, within a few hours of birth. But the human baby is absolutely

dependent and helpless, unable even to manufacture all the animal heat that he

requires. The study of his condition at birth at once suggests a number of

practical procedures, some of them quite at variance with the traditional

procedures.

HOW THE CHILD DEVELOPS

Condition at Birth

Let us see, then, exactly what his condition is. In the first place, he is,

as Virchow, an authority on physiological subjects declares, merely a spinal

animal. Some of the higher brain centers do not yet exist at all, while others

are in too incomplete a state for service. The various

sensations which the baby experiences—heat, light, contact, motion,

etc.—are so many stimuli to the development of these centers. If the

stimulus is too great, the development is sometimes unduly hastened, with

serious results, which show themselves chiefly in later life. The child who is

brought up a noisy room, is constantly talked to and fondled, is likely to

develop prematurely, to talk and walk at an early age;

also to fall into nervous decay at an early age. And even if by reason of an

unusually good heredity he escapes these dangers, it is almost certain that his

intellectual power is not so great in adult life as it would have been under

more favorable conditions. A new baby, like a young plant, requires darkness

and quiet for the most part. As he grows older, and shows a spontaneous

interest in his surroundings, he may fittingly have more light, more

companionship, and experience more sensations.

Weight at Birth

The average boy baby weighs about seven pounds at birth; the average girl,

about six and a half pounds. The head is larger in proportion to the body than

in after life; the nose is incomplete, the legs short and bowed, with a

tendency to fall back upon the body with the knees flexed. This natural

tendency should be allowed full play, for the flexed position is said to be

favorable to the growth of the bones, permitting the cartilaginous ends of the

bones to lie free from pressure at the joints.

The plates of the skull are not complete and do not fit together at the

edges. Great care needs to be taken of the soft spot

thus left exposed on the top of the head—the undeveloped place where the

edges of these bones come together. Any injury here in early life is liable to

affect the mind.

State of Development

The bony enclosures of the middle ear are unfinished and the eyes also are

unfinished. It is a question yet to be settled, whether a new-born baby is

blind and deaf or not. At a rate, he soon acquires a sensitiveness to both

light and sound, although it is three years or more before he has amassed

sufficient experience to estimate with accuracy the distance of objects seen or

herd. He can cry, suck, sneeze, cough, kick, and hold on to a finger. All of

these acts, though they do not yet imply personality, or even mind, give

evidence of a wonderful organism. They require the co-operation of many

delicate nerves and muscles—a co-operation that has as yet baffled the

power of scientists to explain.

Although the young baby is in almost constant motion while he is awake, he

is altogether too weak to turn himself in bed or to escape from an

uncomfortable position, and he remains so for many weeks. This constant motion

is necessary to his muscular development, his control of

his own muscles, his circulation, and, very probably, to the free transmission

of nervous energy. Therefore, it is of the first importance that he has freedom

to move, and he should be given time every day to move and stretch before the

fire, without clothes on. It is well to rub his back and legs at the same time,

thus supplementing his gymnastics with a gentle massage.

Educational Beginnings.

By the time he is four or five weeks old it is safe to play with him, a

little every day, and Froebel has made his "Play with

the Limbs" one of his first educational exercises. In this play the mother lays

the baby, undressed, upon a pillow and catches the little ankles in her hands.

Sometimes she prevents the baby from kicking, so that he has to struggle to get

his legs free; sometimes she helps him, so that he kicks more freely and

regularly; sometimes she lets him push hard against her breast. All the time

she laughs and sings to him, and Froebel has made a little song for this

purposes. Since consciousness is roused and

deepened by sensations, remembered, experienced, and compared, it is evident

that this is more than a fanciful play; that it is what Froebel claimed for

it—a real educational exercise. By means, of it the child may gain some

consciousness of companionship, and thus, by contrast, a deeper

self-consciousness.

First Efforts

The baby is at first unable to hold up its head, and in this he is just like

all other animals, for no animal, except man, holds up its head constantly. The

human baby apparently makes the effort, because he desires to see more

clearly—he could doubtless see clearly enough for all physical purposes

with his head hung down, but not enough to satisfy his awakening mentality. The

effort to hold the head up and to look around is therefore regarded by most

psychologists as one of the first tokens of an awakening intellectual life. And

this is true, although the first effort seems to arise from an overplus of

nervous energy which makes the neck muscles contract, just as it makes other

muscles contract. The first slight raisings of the head are like the first

kicking movements, merely impulsive; but the child soon sees the advantage of

this apparently accidental movement and tries to master it. Preyer

[A] considers that

the efforts to balance the head among the first indications that the child's

will is taking possession of his muscles. His own boy arrived at this point

when he was between three and four months old.

Reflex Grasping

The grasp of the new-born baby's hand has a surprising power, but the baby

himself has little to do with it. The muscles act because of a stimulus

presented by the touch of the fingers, very much as the muscles of a

decapitated frog contract when the current of electricity passes over them.

This is called reflex grasping, and Dr. Louis Robinson,

[B] thinking that

this early strength of gasp was an important illustration of and evidence for

evolution, tried experiments on some sixty new-born babies. He found that they

could sustain their whole weight by the arms alone when their hands were

clasped about a slender rod. They grasped the rod at once and could be lifted

from the bed by it and kept in this position about half a minute. He argued

that this early strength of arm, which soon begins to disappear, was survival

from the remote period when the baby's ancestors were monkeys or monkey-like

people who lived in trees.

Beginnings Of Will Power

However this may be, during the first week the baby's hands are much about

his face. By accident they reach, the mouth, they are sucked; the child feels

himself suck its own fist; he feels his fist being sucked. Some day it will

occur to him that that fist belongs to the same being who owns the sucking

mouth. But at this point, Miss Shinn[C]

has observed, the baby is often surprised

and indignant that he cannot move his arms around and at the same time suck his

fist. This discomfort helps him to make an effort to get his fist into his

mouth and keep it there, and this effort shows his will, beginning to take

possession of his hands and arms.

Growth of Will

Since any faculty grows by its own exercise, just as muscles grow by

exercise, every time the baby succeeds in getting his hands to his mouth as a

result of desire, every time that he succeeds in grasping an object as result

of desire, his will power grows. Action of this nature brings in new

sensations, and the brain centers used for recording such sensations grow.

As the sensations multiply, he compares them, and an idea is born. For the

beginnings of mental development no other mechanism is actually needed than a

brain and a hand and the nerves connecting them. Laura Bridgeman and Helen

Keller, both of them deaf and blind, received their education almost entirely

through their hands, and yet they were unusually capable of thinking. The

child's hands, then, from the beginning, are the servants of his

brain-instruments by means of which he carries impressions from the outer world

to the seat of consciousness, and by which in turn he imprints his

consciousness upon the outer world.

Intentional Grasping

The average baby does not begin to grasp objects with intention before the

fourth month. The first grasping seems to be done by feeling, without the aid

of the eye, and is done with the fingers with no attempt to oppose the thumb to

them. So closely does the use of the thumbs set opposite the fingers in

grasping coincide with the first grasping with the aid of sight, that some

observers have been led to believe that as soon as the baby learns to use its

thumb in this way he proves that he is beginning to grasp with intention.

Order of Development

The order of development seems to be, first, automatism, the muscles

contracting of themselves in response to nervous stimuli; second,

instinct, the inherited wisdom of the race, which

discovered ages ago that the hand could be used to greater advantage when the

thumb was separated from the fingers; and thirdly, the child's own

intelligence and will making use of this natural and inherited machinery. This

order holds true of the development, not only of the hand, but of the whole

organism.

Looking

A little earlier than this, during the third month, the baby first looks

upon his own hands and notices them. Darwin tells us that

his boy looked at his own hands and seemed to study them until his eyes

crossed. About the same then the child notices his foot and uses his hand to

carry it to its mouth. It is some time later that he discovers that he can move

his feet without his hands.

Tearing

About this time, three or four months old, the child begins to tear paper

into pieces, and may be easily taught to let the piece, that have found their

way into his mouth be taken out again. Now, too, he begins to throw things, or

to drop them; then he wants to get them back again, and the patient mother must

pick them up and give them back many times. Sometimes a baby is punished for

this proclivity, but it is really a part of his development, and at least once

a day he should be allowed to play in this manner to his heart's content. It is

tact, not discipline, that is needed, and the more he is helped the sooner he

will live through this stage and come to the next point where he begins to

throw things.

Throwing

In this stage, of course, he must be given the proper things to

throw—small, bright-colored worsted balls, bean-bags, and other harmless

objects. If he is allowed to discover the pleasure there is in smashing glass

and china, he will certainly be, for a time, a very destructive little person.

When later he is able to creep throw his ball and creep after it—he will

amuse himself for hours at a time, and so relieve those who have patiently

attended him up to this time. In general we may lay down the rule, that the

more time and attention of the right sort is to a young child, the less will

need to be given as he grows older. It is poor economy to neglect a young

child, and try to make it up on the growing boy or girl. This is to substitute

a complicated and difficult problem for a simple one.

The Grasping Instinct

It is some time before a child's will can so overcome his newly-acquired

tendency to grasp every possible object that he can keep his hand off of

anything that invites him. The many battles between mothers and children it the

subject of not touching forbidden things are at this

stage a genuine wrong and injustice to the child. So young a child is scarcely

more responsible for touching whatever he can reach that is a piece of steel

for being drawn toward a powerful magnet. Preyer says

that it is years before voluntary inhibitions of grasping become possible. The

child has not the necessary brain machinery. Commands

and sparring of the hands create bewilderment and tend to build up a barrier

between mother and child. Instead of doing such thing, simply put high out of

reach and sight whatever the child must not touch.

Another way in which young children are often made to suffer because of the

ignorance of parents is the leaving of undesired

food on the child's plate. Every child, when he does not want his food, pushes

the plate away from him, and many mothers push it back and scold. The real

truth is that the motor suggestion of the food upon the plate is so strong that

the child feels as if he were being forced to eat it every time he looks at the

plate; to escape from eating it he is obliged to push it out of sight.

The Three Months' Baby

But this difficulty comes later. Now we are concerned with a

three-months-old baby. At this stage the child is usually able to balance his

head, to sit up against pillows, to seize and grasp objects, and to hold out

his arm, when he wishes to be taken. Although he may have made number of

efforts to sit erect, and may have succeeded for a few minutes at a time, he

still is far from being able to sit alone, unsupported. This he does not

accomplish until the fifth or the month.

Danger of Forcing

There is nothing to be gained by trying to make him sit alone sooner;

indeed, there is danger in it—danger in forcing young bones and muscles

to do work beyond their strength, and danger also to the nerves. It is safe to

say that a normal child always exercises all its

faculties to the utmost without need of urging, and any exercise beyond the

point of natural fatigue, if persisted in, is sure to bring about abnormal

results.

Creeping

The first efforts toward creeping often appear in the bath when the child

turns over and raise, himself upon his hands and knees. This is sign that he

might creep sooner, if he were not impeded by clothing. He should be allowed to

spread himself upon a blanket every day for an hour or two, and to get on his

knees as frequently as he pleases. Often he needs a little help to make him

creep forward, for most babies creep backward at first, their arms being

stronger than their legs. Here the mother may safely interfere, pushing the

legs as they ought to go and showing the child how to manage himself; for very

often he becomes much excited over his inability to creep forward.

The climbing instinct begins to appear by this time—the seventh

month—and here the stair-case has its great advantages. It ought not to

be shut from him by a gate, but he should be taught how to climb up and down it

in safety. To do this, start him at the head of the stairs, and, you yourself

being below him, draw first one knee and then the other over the step, thus

showing him how to creep backward. Two lessons of about twenty minutes each

will be sufficient. The only danger is creeping down head foremost, but if he

once learns thoroughly to go backward, and has not been allowed the other way

at all, he will never dream of trying it. In going down backward, if he should

slip, he can easily save himself by catching the stairs with his hands as he

slips past.

The child who creeps is often later in his attempts to walk than the child

who does not; and, therefore, when he is ready to walk, his legs will be all

the stronger, and the danger of bow-legs will be past. As long as the child

remains satisfied with creeping, he is not yet ready either mentally or

physically for walking.

Standing

If the child has been allowed to creep about freely, he will soon be

standing. He will pull himself to his feet by means of any chair, table, or

indeed anything that he may get hold of. To avoid injuring him, no flimsy

chairs or spindle-legged tables should be allowed in his nursery. He will next

begin to sidle around a chair, shuffling his feet in a vague fashion, and

sometimes, needing both of his hands to seize some coveted object, he will

stand without clinging, leaning on his stomach. An unhurried child may remain

at this stage for weeks.

Walking

Let alone, as he should be, he will walk without knowing how he does it, and

will be the stronger for having overcome his difficulties himself. He should

not be coaxed to stand or walk. The things in his room actually urge him to

come and get them. Any further persuasion is forced, and may urge him beyond

his strength.

Walking-chairs and baby-jumpers are injurious in this respect. They keep the

child from his native freedom of sprawling, climbing, and pulling himself up.

The activity they do permit is less varied and helpful than the normal

activity, and the child, restricted from the preparatory motions, begins to

walk too soon.

Alternate Growth

A curious fact in the growth of children is that they seem to grow heavier

for a certain period, and then to grow taller for a similar period. That is, a

very young baby, say, two months old, will grow fatter for about six weeks, and

then for the next six weeks will grow longer, while the child of six years

changes his manner of growth every three or four months. These periods are

variable, or at least their law has not yet been

established, but the observant mother can soon make the period out for herself

in the case of her own child. For two or three days, when the manner of growth

seems to be changing from breadth to length, and vice versa, the children are

likely to be unusually nervous and irritable, and these aberrations must, of

course, be patiently borne with.

Precocity

Early Ripening

In all these things some children develop earlier than others, but too early

development is to be regretted. Precocious children are always of a delicate

nervous organization. Fiske

[D] has proved to us

that the reason why the human young is so far more helpless and dependent than

the young of any other species is because the activities of the human race have

become so many, so widely varied, and so complex, that they could not fix

themselves in the nervous structure before birth. There a only a few things

that the chick needs to know in order to lead a successful chicken life; as a

consequence these few things are well impressed upon the small brain before

ever he chips the shell; but the baby needs to learn a great many

things—so many that there is no time or room to implant them before

birth, or indeed, in the few years immediately succeeding birth. To hurry the

development, therefore, of certain few of these faculties, like the faculties

of talking, and walking, of imitation or response, is to crowd out many other

faculties perhaps just beginning to grow. Such forcing will limit the child's

future development to the few faculties whose growth is thus early stimulated.

Precocity in a child, therefore, is a thing to be deplored. His early ripening

foretells a early decay and a wise mother is she who gives her child ample

opportunity for growing, but no urging.

Ample Opportunity for Growth

Ample opportunity for growth includes (1) Wholesome surroundings, (2)

Sufficient sleep, (3) Proper clothing, (4) Nourishing food. We will take up

these topics in order.

[A]

W. Preyer. Professor of Physiology, of Jena, author of "The Mind of the

Child." D. Appleton & Co.

[B]

Dr. Robinson. Physician and Evolutionist, paper in The Eclectic, Vol.

29.

[C]

Miss Millicent Shinn, American Psychologist, author of "Biography of a

Baby."

[D]

John Fiske, writer on Evolutionary Philosophy. His theory of infancy is

perhaps his most important contribution to science.

WHOLESOME SURROUNDINGS

The whole house in which the child lives ought to be well warmed and equally

well aired. Sunlight also is necessary to his

well-being. If it is impossible to have this in every room, as sometimes

happens in city homes, at least the nursery must have it. In the central States

of the Union plants and trees exposed to the southern sun put forth their

leaves two weeks sooner than those exposed to the north. The infant cannot fail

to profit by the same condition, for the young child may be said to lead in

part a vegetative as well as an animal life, and to need air and sunshine and

warmth as much as plants do. The very best room in the house is not too good

for the nursery, for in no other room is such important and delicate work being

done.

Temperature

The temperature is a matter of importance. It should not be decided by

guess-work, but a thermometer should be hung upon a

wall at a place equally removed from draft and from the source of heat. The

temperature for children during the first year should be about 70 degrees

Fahrenheit during the day and not lower than 50 degrees at night. Children who

sleep with the mother will not be injured by a temperature 5 to 20 degrees

lower at night.

Fresh Air

It is important to provide means for the ingress of fresh air. It is not

sufficient to air the room from another room unless that other room has in it

an open window. Even then the nursery windows should be opened wide from

fifteen minutes to half an hour night and morning, while the child is in

another room; and this even when the weather is at zero or below. It does not

take long to warm up room that has been aired. Perhaps the best means of

obtaining the ingress of fresh air without creating a draft upon the floor,

where the baby spends so much of his time, is to raise the window six inches at

the top or bottom and insert a board cut to fit the aperture.

Daily Outing

But no matter how well ventilated the nursery may be, all children more than

six weeks old need unmodified outside air, and need it every day, no matter

what the weather, unless they are sick.

The daily outing secures them better appetites, quiet sleep, and calmer

nerves. Let them be properly clothed and protected in their carriages, and all

weathers are good for them.

Children who take their naps in their baby-carriages may with advantage be

wheeled into a sheltered spot, covered warmly, and left to sleep in the outer

air. They are likely to sleep longer than in the house, and find more

refreshment in their sleep.

SUFFICIENT SLEEP.

Few children in America get as much sleep as they really need.

Preyer gives the record of his own child, and the hours which

this child found necessary for his sleep and growth may be taken for a

standard. In the first month, sixteen, in full, out of twenty-four hours were

spent in sleep. The sleep rarely lasted beyond two hours at a time. In the

second month about the same amount was spent in sleep, which lasted from three

to six hours at a time. In the sixth month, it lasted from six to eight hours

at a time, and began to diminish to fifteen hours in the twenty-four. In the

thirteenth month, fourteen hours' sleep daily; it the seventeenth, prolonged

sleep began, ten hours without interruption; in the twentieth, prolonged sleep

became habitual, and sleep in the day-time was reduced to two hours. In the

third year, the night sleep lasted regularly from eleven to twelve hours, and

sleep in the daytime was no longer required.

Naps

Preyer's record stops here. But it may be added that children from three to

eight years still require eleven hours' sleep; and, although the child of three

nay not need a daily nap, it is well for him, until he is six years old, to lie

still for an hour in the middle of the day, amusing himself with a picture book

or paper and pencil, but not played with or talked to by any other person. Such

a rest in the middle of the day favors the relaxation of muscles and nerves and

breaks the strain of a long day of intense activity.

PROPER CLOTHING.

Proper clothing for a child includes three things: (a) Equal distribution of

warmth, (b) Freedom from restraint, (c) Light weight.

Equal distribution of warmth is of great importance, and is seldom

attained. The ordinary dress for a young baby, for example, leaves the arms and

the upper part of the chest unprotected by more than one thickness of flannel

and one of cotton—the shirt and the dress. About the child's middle, on

the contrary, there are two thicknesses of flannel—a shirt and

band—and five of cotton, i.e., the double bands of the white and flannel

petticoats, and the dress. Over the legs, again, are two thicknesses of flannel

and two of cotton, i.e., the pinning blanket, flannel skirt, white skirt, and

dress. The child in a comfortably warm house needs two thicknesses of flannel

and one of cotton all over it, and no more.

The Gertrude Suit

The practice of putting extra wrappings about the abdomen is responsible for

undue tenderness of those organs. Dr. Grosvenor, of Chicago, who designed a

model costume for a baby, which he called the Gertrude suit,

says that many cases of rupture are due to bandaging

of the abdomen. When the child cries the abdominal walls normally expand; if

they are tightly bound, they cannot do this, and the pressure upon one single

part, which the bandages may not hold quite firmly, becomes overwhelming, and

results in rupture. Dr. Grosvenor also thinks that many cases of

weak lungs, and even of consumption in later life, are due to

the tight bands of the skirts pressing upon the soft ribs of the young child,

and narrowing the lung space.

Objection to the Pinning Blanket

Freedom from restraint.. Not only should the clothes not bind the

child's body in any way, but they should not be so long as to prevent free

exercise of the legs. The pinning-blanket is objectionable on this account. It

is difficult for the child to kick in it; and as we have seen before, kicking

is necessary to the proper development of the legs. Undue length of skirt

operates in the same way—the weight of cloth is a check upon activity.

The first garment of a young baby should not be more than a yard in length from

the neck to the bottom of the hem, and three-quarters of a yard is enough for

the inner garment.

The sleeves, too, should be large and loose, and the arm-size should be

roomy, so as to prevent chafing. The sleeves may be tied in at the wrist with a

ribbon to insure warmth.

Lightness of weight. The underclothing

should be made of pure wool, so as to gain the greatest amount of warmth from

the least weight. In the few cases where wool would cause irritation, a silk

and wool fixture makes a softer but more expensive garment. Under the best

conditions, clothes restrict and impede free development somewhat, and the

heavier they are the more they impede it. Therefore, the effort should be to

get the greatest amount of warmth with the least possible weight.

Knit garments attain this most perfectly, but the next best

thing is all-wool flannel of a fine grade. The weave known as stockinet is best

of all, because goods thus made cling to the body and yet restrict its activity

very little.

The best garments for a baby are made according to the accompanying

diagram.

Princess Garment

They consist of three garments, to be worn one over the other, each one an

inch longer in every way than the underlying one. The first is a princess

garment, made of white stockinet, which takes the place of shirt,

pinning-blanket, and band. Before cutting this out, a box-pleat an inch and a

half wide should be laid down the middle of the front, and a side pleat

three-fourths of an inch wide on either side of the placket in the back. The

sleeve should have a tuck an inch wide. These tucks and pleats are better run

in be hand, so that they may be easily ripped. As the baby grows and the

flannel shrinks, these tucks and pleats can be let out.

The next garment, which goes over this, is made in the same way, only an

inch larger in every measurement. It is made of baby flannel, and takes the

place of the flannel petticoat with its cotton band. Over these two garments

any ordinary dress may be worn. Dressed in this suit, the child is evenly

covered with too thicknesses of flannel and one of cotton. As the skirts are

rather short, however, and he is expected to move his legs about freely, he may

well wear long white wool stockings.

As the child grows older, the principles underlying this method of clothing

should be borne in mind, and clothes should be designed and adapted so as to

meet these three requirements.

FOOD.

Natural Food

Bottle-fed Babies

The natural food of a young baby is his mother's milk, and no satisfactory

substitute for it has yet been found. Some manufactured baby foods do well for

certain children; to others they are almost poison; and for none of them are

they sufficient. The milk of the cow is not designed for the human infant. It

contains too much casein, and is too difficult of digestion. Various

preparations of milk and grains are recommended by nurses and physicians, but

no conscientious nurse or physician pretends that any of them begins to equal

the nutritive value of human milk. More women can nurse their babies than now

think they can; the advertisements of patent foods lead them to think the

rather of little importance, and they do not make the necessary effort to

preserve and increase the natural supply of milk. The family physician can

almost always better the condition of the mother who really desires to nurse

her own child, and he should be consulted and his directions obeyed. The

importance of a really great effort to this direction is shown by the fact that

the physical culture records, now so carefully

kept in many of our schools and colleges, prove that

bottle-fed babies are more likely to be of small stature, and to

have deficient bones, teeth and hair, than children who have been fed on

mother's milk.

Simple Diet

The food question is undoubtedly the most important problem to the physical

welfare of the child, and has, as well, a most profound effect upon his

disposition and character. Indiscriminate feeding is

the cause of much of the trouble and worry of mothers. This subject is taken up

at length in other papers of this course, and it will suffice to say here that

the table of the family with young children should be regulated largely by the

needs of the growing sons and daughters. The simplified diet necessary may well

be of benefit to other members of the family.

FAULTS AND THEIR REMEDIES.

The child born of perfect parents, brought up perfectly, in a perfect

environment, would probably have no faults. Even such a child, however, would

be at times inconvenient, and would do and say things at

variance with the order of the adult world. Therefore he might seem to a hasty,

prejudiced observer to be naughty. And, indeed, imperfectly born, imperfectly

trained as children now are, many of their so-called faults are no more than

such inconvenient crossings of an immature will with an adult will.

The Child's World and the Adult's World

No grown person, for instance, likes to be interrupted, and is likely to

regard the child who interrupts him wilfully naughty. No young child, on the

contrary, objects to being interrupted in his speech, though he may object to

being interrupted in his play; and he cannot understand why an adult should set

so much store on the quiet listening which is so infrequent in his own

experience. Grown persons object to noise; children delight in it. Grown

persons like to have things kept in their places; to a child, one place as good

as another. Grown persons have a prejudice in favor of cleanliness; children

like to swim, but hate to wash, and have no objections whatever to grimy hands

and faces. None of these things imply the least degree of obliquity on the

child's part; and yet it is safe to say that nine-tenths of the children who

are punished are punished for some of these things. The remedy for these

inconveniences is time and patience. The child, if left to himself, without a

word of admonishment, would probably change his conduct in these respects,

merely by the force of imitation, provided that the adults around him set him,

a persistent example of courtesy, gentleness, and cleanliness.

Real Faults

The faults that are real faults, as Richter[A] says, are those faults which increase

with age. These it is that need attention rather than those that disappear of

themselves as the child grows older. This rule ought to be put in large

letters, that every one who has to train children may be daily reminded by it;

and not exercise his soul and spend his force in trying to overcome little

things which may perhaps be objectionable, but which will vanish to-morrow.

Concentrate your energies on the overcoming of such tendencies as may in time

develop into permanent evils.

Training the Will

To accomplish this, you most, of course, train the child's own will, because

no one can force another person into virtue against his will. The chief object

of all training is, as we shall see in the next section, to lead the child to

love righteousness, to prefer right doing to wrong doing; to make

right doing a permanent desire. Therefore, in all the

procedures about to be suggested, an effort is made to convince the child of

the ugliness and painfulness of wrong doing.

Natural Punishment

Punishment, as Herbert Spencer

[B] agrees with

Froebel[C] in

pointing out, should be as nearly as possible a representation of the natural

result of the child's action; that is, the fault should be made to punish

itself as much as possible without the interference of any outside person; for

the object is not to make the child bend his will to the will of another, but

make him see the fault itself as an undesirable thing.

Breaking the Will

The effort to break the child's will has long been recognized as disastrous

by all educators. A broken will is worse misfortune than a broken back. In the

latter case the man is physically crippled; in the former, he is morally

crippled. It is only a strong, unbroken, persistent will that is adequate to

achieve self-mastery, and mastery of the difficulties of

life. The child who is too yielding and obedient in his early days is only too

likely to be weak and incompetent in his later days. The habit of submission to

a more mature judgment is a bad habit to insist upon. The child should be

encouraged to think out things for himself; to experiment and discover for

himself why his ideas do not work; and to refuse to give them up until he is

genuinely convinced of their impracticability.

Emergencies

It is true that there are emergencies in which his

immature judgment and undisciplined

will must yield to wiser judgment and steadier will; but such yielding should

not be suffered to become habitual. It is a safety valve merely, to be employed

only when the pressure of circumstances threatens to become dangerous. An

engine whose safety valve should be always in operation could never generate

much power. Nor is there much difficulty in leading even a very strong-willed

and obstinate child to give up his own way under extraordinary circumstances.

If he is not in the habit of setting up his own will against that of his mother

or teacher, he will not set it up when the quick, unfamiliar word of command

seems to fit in the with the unusual circumstances. Many parents practice

crying "Wolf! wolf!" to their children, and call the practice a drill of

self-control; but they meet inevitably with the familiar consequences: when the

real wolf comes the hackneyed cry, often proved false, is disregarded.

Disobedience

When the will is rightly trained, disobedience is a fault that rarely

appears, because, of course, where obedience is seldom required, it is seldom

refused. The child needs to obey—that is true; but so does his mother

need to obey, and all other persons about him. They all need to obey God, to

obey the laws of nature, the impulses of kindness, and to follow after the ways

of wisdom. Where such obedience is a settled habit of the entire household, it

easily, and, as it were, unconsciously, becomes the habit of the child. Where

such obedience is not the habit of the household, it is only with great

difficulty that it can become the habit of the child. His will must set itself

against its instinct of imitativeness, and his small

house, not yet quite built, must be divided against itself. Probably no cold

even rendered entire obedience to any adult who did not himself hold his own

wishes in subjection. As Emerson says, "In dealing with my child, my Latin and

my Greek, my accomplishments and my money, stead me nothing, but as much soul

as I have avails. If I a willful, he sets his will against mine, one for one,

and leaves me, if I please, the degradation of beating him by my superiority of

strength. But, if I renounce my will and act for the soul, setting that up as

an umpire between us two, out of his young eyes looks the same soul; he reveres

and loves with me."

Negative Goodness

Suppose the child to be brought to such a stage that he is willing to do

anything his father or mother says; suppose, even, that they never tell him to

do anything that he does not afterwards discover to be reasonable and just;

still, what has he gained? For twenty years he has not had the responsibility

for a single action, for a single decision, right or wrong. What is permitted

is right to him; what is forbidden is wrong. When he goes out into the world

without his parents, what will happen? At the best he will not lie, or steal,

or commit murder. That is, he will do none of these things in their bald and

simple form.

But in their beginnings these are hidden under a mask of virtue and he has

never been trained to look beneath that mask; as happened to Richard Feveril,

[D] sin may

spring upon him unaware. Some one else, all his life, has labeled things for

him; he is not in the habit of judging for himself. He is blind, deaf, and

helpless—a plaything of circumstances. It is a chance whether he falls

into sin or remains blameless.

Real Disobedience

Disobedience, then, in a true sense, does not mean failure to do as he is

told to do. It means failure to do the things that he knows to be right. He

must be taught to listen and obey the voice of his own conscience; and if that

voice should ever speak, as it sometimes does, differently from the voice of

the conscience of his parents or teachers, its dictates must still be respected

by these older and wiser persons, and he must be permitted to do this thing

which in itself may be foolish, but which is not foolish, to him.

Liberty

And, on the other hand, the child who will have his own way even when he

knows it to be wrong should be allowed to have it within reasonable limits.

Richter says, leave to him the sorry victory, only exercising sufficient

ingenuity to make sure that it is a sorry one. What he must be taught is that

it is not at all a pleasure to have his own way, unless his own way happens to

be right; and this he can only be taught by having his own way when the results

are plainly disastrous. Every time that a willful

child does what he wants to do, and suffers sharply for it, he learns a lesson

that nothing but this experience can teach him.

Self-Punishment

But his suffering must be plainly seen to be the result of his deed, and not

the result of his mother's anger. For example, a very young child who is

determined to play with fire may be allowed to touch the hot lamp or a stove,

whenever affairs can be so arranged that he is not likely to burn himself too

severely. One such lesson is worth all the hand-spattings and cries of "No,

no!" ever resorted to by anxious parents. If he pulls down the blocks that you

have built up for him, they should stay down, while you get out of the room, if

possible, in order to evade all responsibility for that unpleasant result.

Prohibitions are almost useless. In order to convince yourself of this, get

some one to command you not to move your right arm or to wink your eye. You

will find it almost impossible to obey for even a few moments. The desire to

move your arm, which was not at all conscious before, will become overpowering.

The prohibition acts like a suggestion, and is an implication that you would do

the negative act unless you were commanded not to. Miss Alcott, in "Little

Men," well illustrates this fact in the story of the children who were told not

to put beans up their noses and who straightway filled their noses with

beans.

Positive Commands

As we shall see in the next section, Froebel meets this difficulty by

substituting positive commands for prohibitions; that is, he tells the child to

do instead of telling him not to do. Tiedemann

[E] says that example

is the first great evolutionary teacher, and liberty is the second. In the

overcoming of disobedience, no other teachers are needed. The method may be

tedious; it may be many years before the erratic will is finally led to work in

orderly channels; but there is no possibility of abridging the process. There

is no short and sudden cure for disobedience, and the only hope for final cure

is the steady working of these two great forces, example and

liberty.

To illustrate the principles already indicated, we will consider some

specific problems together with suggestive treatment for each.

[Footnote A: Jean Paul Richter, "Der einsige." German writer and philosopher.

His rather whimsical and fragmentary book on education, called "Levana,"

contains some rare scraps of wisdom much used by later writers on educational

topics.] [Footnote B: Herbert Spencer, English Philosopher and Scientist. His

book on "Education" is sound and practical.] [Footnote C: Freidrich Froebel,

German Philosopher and Educator, founder of the Kindergarten system, and

inaugurator of the new education. His two great books are "The Education of

Man" and "The Mother Play."] [Footnote D: "The Ordeal of Richard Feveril," by

George Meredith.] [Footnote E: Tiedemann, German Psychologist.]

[A]

Jean Paul Richter, "Der einsige." German writer and philosopher. His rather

whimsical and fragmentary book on education, called "Levana," contains some

rare scraps of wisdom much used by later writers on educational topics.

[B]

Herbert Spencer, English Philosopher and Scientist. His book on "Education"

is sound and practical.

[C]

Freidrich Froebel, German Philosopher and Educator, founder of the

Kindergarten system, and inaugurator of the new education. His two great books

are "The Education of Man" and "The Mother Play."

[D]

"The Ordeal of Richard Feveril," by George Meredith.

[E]

Tiedemann, German Psychologist.

QUICK TEMPER.

This, as well as irritability and nervousness, very often springs from a

wrong physical condition. The digestion may be bad, or the child may be

overstimulated. He may not be sleeping enough, or may not get enough outdoor

air and exercise. In some cases the fault appears because the child lacks the

discipline of young companionship. Even the most exemplary adult cannot make up

to the child for the influence of other children. He perceives the difference

between himself and these giants about him, and the perception sometimes makes

him furious. His struggling individuality finds it difficult to maintain itself

under the pressure of so many stronger personalities. He makes, therefore,

spasmodic and violent attempts of self-assertion, and these attempts go under

the name of fits of temper.

The child who is not ordinarily strong enough to assert himself effectively

will work himself up into a passion in order to gain strength, much as men

sometimes stimulate their courage by liquor. In fact, passion is a sort of

moral intoxication.

Remedy—Solitude and Quiet

But whether the fits of passion are physical or moral, the immediate remedy

is the same—his environment must be promptly changed and his audience

removed. He needs solitude and quiet. This does not mean shutting him into a

closet, but leaving him alone in a quiet room, with plenty of pleasant things

about. This gives an opportunity for the disturbed organism to right itself,

and for the will to recover its normal tone. Some occupation should be at

hand—blocks or other toys, if he is too young to read; a good book or

two, such as Miss Alcott's "Little Men" and "Little Women," when he is old

enough to read.

If he is destructive in his passion, he must be put in a room where there

are very few breakables to tempt him. If he does break anything he must be

required to help mend it again. To shout a threat to this effect through the

door when the storm of temper is still on, is only to goad him into fresh acts

of rebellion. Let him alone while he is in this temporarily insane state, and

later, when he is sorry and wants to be good, help him to repair the mischief

he has wrought. It is as foolish to argue with or to threaten the child in this

state as it would be were he a patient in a lunatic asylum.

It is sometimes impossible to get an older child to go into retreat. Then,

since he cannot be carried, and he is not open to remonstrance or commands, go

out of the room yourself and leave him alone there. At any cost, loneliness and

quiet must be brought to bear upon him.

Such outbursts are exceedingly exhausting, using up in a few minutes as much

energy as would suffice for many days of ordinary activity. After the attack

the child needs rest, even sleep, and usually seeks it himself. The desire

should be encouraged.

Precautions to be Taken

Every reasonable precaution should be taken against the recurrence of the

attacks, for every lapse into this excited state makes him more certain the

next lapse and weakens the nervous control. This does not mean that you should

give up any necessary or right regulations for fear of the child's temper. If

the child sees that you do this, he will on occasion deliberately work himself

up into a passion in order to get his own way. But while you do not relax any

just regulations, you may safely help him to meet them. Give him warning. For

instance, do not spring any disagreeable commands

upon him. Have his duties as systematized as possible so that he may know what

to expect; and do not under any circumstances nag him nor allow other children

to tease him.

SULLENNESS.

This fault likewise often has a physical cause, seated very frequently in

the liver. See that the child's food is not too heavy. Give him much fruit, and

insist upon vigorous exercise out of doors. Or he may perhaps not have enough

childish pleasures. For while most children are overstimulated, there still

remain some children whose lives are unduly colorless and eventless. A sullen

child is below the normal level of responsiveness.

He needs to be roused, wakened, lifted out of himself, and made to take an

active interest in other persons and in the outside world.

Inheritance and Example

In many cases sullenness is an inherited

disposition intensified by example. It is unchildlike and morbid to an unusual

degree and very difficult to cure. The mother of a sullen child may well look

to her own conduct and examine with a searching eye the peculiarities of her

own family and of her husband's. She may then find the cause of the evil, and

by removing the child from the bad example and seeing to it that every day

contains a number of childish pleasures, she may win him away from a fault that

will otherwise cloud his whole life.

LYING.

All lies are not bad, nor all liars immoral. A young child who cannot yet

understand the obligations of truthfulness cannot

be held morally accountable for his departure from truth. Lying is of three

kinds.

(1.) The imaginative lie. (2.) The evasive lie. (3.) The

politic lie.

Imaginative "Lying"

(1.) It is rather hard to call the imaginative lie a lie at all. It is so

closely related to the creative instinct which makes the poet and novelist and

which, common among the peasantry of a nation, is responsible for folk-lore and

mythology, that it is rather an intellectual activity misdirected than a moral

obliquity. Very imaginative children often do not know the difference between

what they imagine and what they actually see. Their minds eye sees as vividly

as their bodily eye; and therefore they even believe their own statements.

Every attempt at contradiction only brings about a fresh assertion of the

impossible, which to the child becomes more and more certain as he hears

himself affirming its existence.

Punishment is of no use at all in the attempt to regulate this exuberance.

The child's large statements should be smiled at and passed over. In the

meantime, he should be encouraged in every possible way to get a firm, grasp of

the actual world about him. Manual training, if it can be obtained, is of the

greatest advantage, and for a very young child, the performance every day of

some little act, which demands accuracy and close attention, is necessary. For

the rest, wait; this is one of the faults that disappear with age.

The Lie of Evasion

(2.) The lie of evasion is a form of lying which seldom appears when the

relations between child and parents are absolutely friendly and open. However,

the child who is very desirous of approval may find it difficult to own up to a

fault, even when he is certain that the consequence of his offense will not be

at all terrible. This is the more difficult, because the more subtle condition.

It is obvious that the child who lies merely to avoid punishment can be cured

of that fault by removing from him the fear of punishment. To this end, he

should be informed that there will be no punishment whatever for any fault that

he freely confesses. For the chief object of punishment

being to make him face his own fault and to see it as something ugly and

disagreeable, that object is obviously accomplished by a free and open

confession, and no further punishment is required.

But when the child in spite of such reassurance still continues to lie, both

because he cannot bear to have you think him capable of wrong-doing, and

because he is not willing to acknowledge to himself that he is capable of

wrong-doing, the situation becomes more complex. All you can do is to urge upon

him the superior beauty of frankness; to praise him and love him, especially

when he does acknowledge a fault, thus leading him to see that the way to win

your approval—that approval which he desires so intensely—is to

face his own shortcomings with a steady eye and confess them to you

unshrinkingly.

The Politic Lie

(3.) The politic lie is of course the worst form of lying, partly because it

is so unchildlike. This is the kind of fault that will grow with age; and grow

with such rapidity that the mother must set herself against it with all the

force at her command. The child who lies for policy's sake, in order to achieve

some end which is most easily achieved by lying, is a child led into

wrong-doing by his ardent desire to get something or do something. Discover

what this something is, and help him to get it by more legitimate means. If you

point out the straight path, and show the goal well in view, at the end of it,

he may be persuaded not to take the crooked path.

Inherited Crookedness

But there are occasionally natures that delight in crookedness and that even

in early childhood. They would rather go about getting their heart's desire in

some crooked, intricate, underhanded way than by the direct route. Such a fault

is almost certain to be an inherited one; and here again, a close study of the

child's relatives will often help the mother to make a good diagnosis, and even

suggest to her the line of treatment.

Extreme Cases

In an extreme case, the family may unite in disbelieving the child who lies,

not merely disbelieving him, when he is lying, but disbelieving him all the

time, no matter what he says. He must be made to see, and, that without room

for any further doubt, that the crooked paths that he loves do not lead to the

goal his heart desires, but away from it. His words, not being true to the

facts, have lost their value, and no one around him listens to them. He is, as

it were, rendered speechless, and his favorite means of getting his own way is

thus made utterly valueless. Such a remedy is in truth a terrible one. While it

is being administered, the child suffers to the limit of his endurance; and it

is only justified in an extreme case, and after the failure of all gentler

means.

JEALOUSY.

Justice and Love

Too often this deadly evil is encouraged in infancy, instead of being

promptly uprooted as it ought to be. It is very amusing, if one does not

consider the consequences, to sec a little child slap and push away the father

or the older brother, who attempts to kiss the mother; but this is another

fault that grows with years, and a fault so deadly that once firmly rooted it

can utterly destroy the beauty and happiness of an otherwise lovely nature. The

first step toward overcoming it must be to make the reign of strict justice in

the home so obvious as to remove all excuse for the evil. The second step is to

encourage the child's love for those very persons of whom he is most likely to

be jealous. If he is jealous of the baby, give him special care of the baby.

Jealousy indicates a temperament overbalanced

emotionally; therefore, put your force upon the upbuilding of the child's

intellect. Give him responsibilities, make him think out things for himself.

Call upon him to assist in the family conclaves. In every way cultivate his

power of judgment. The whole object of the treatment should be to strengthen

his intellect and to accustom his emotions to find outlet in wholesome, helpful

activity.

One wise mother made it a rule to pet the next to the baby. The baby, she

said, was bound to be petted a good deal because of its helplessness and

sweetness, therefore she made a conscious effort to pet the next to the

youngest, the one who had just been crowded out of the warm nest of mother's

lap by the advent of the newcomer. Such a rule would go far to prevent the

beginnings of jealousy.

SELFISHNESS.

This is a fault to which strong-willed children are especially liable. The

first exercise of will-power after it has passed the stage of taking possession

of the child's own organism usually brings him into conflict with those about

him. To succeed in getting hold of a thing against the wish of someone else,

and to hold on to it when someone else wants it, is to win a victory. The

coveted object becomes dear, not so much for its own sake, as because it is a

trophy. Such a child knows not the joy of sharing; he knows only the joys of

wresting victory against odds. This is indeed an evil that grows with the

years. The child who holds onto his apple, his Candy, or toy, fights tooth and

nail everyone who wants to take it from him, and resists all coaxing, is liable

to become a hard, sordid, grasping man, who stops at no obstacle to accomplish

his purpose.

Yet in the beginning, this fault often hides itself and escapes attention.

The selfish child may be quiet, clean, and under ordinary circumstances,

obedient. He may not even be quarrelsome; and may therefore come under a much

less degree of discipline than his obstreperous, impulsive, rebellious little

brother. Yet, in reality, his condition calls for much more careful attention

than does the condition of the younger brother.

The Only Child

However, the child who has no brother at all, either older or younger, nor

any sister, is almost invited by the fact of his isolation to fall into this

sin. Only children may be—indeed, often are—precocious, bright,

capable, and well-mannered, but they are seldom spontaneously generous. Their

own small selves occupy an undue proportion of the family horizon, and

therefore of their own.

Kindergarten a Remedy

This is where the Kindergarten has its great value. In the true Kindergarten

the children live under a dispensation of loving justice, and selfishness

betrays itself instantly there, because it is alien to the whole spirit of the

place. Showing itself, it is promptly condemned, and the child stands convicted

by the only tribunal whose verdict really moves him—a jury of his peers.

Normal children hate selfishness and condemn it, and the selfish child himself,

following the strong, childish impulse of imitation, learns to hate his own

fault; and so quick is the forgiveness of children that he needs only to begin

to repent before the circle of his mates receives him again.

This is one reason why the Kindergarten takes children at such an early age.

Aiming, as it does, to lay the foundations for right thinking and feeling, it

must begin before wrong foundations are too deeply laid. Its gentle, searching

methods straighten the strong will that is growing crooked, and strengthen the

enfeebled one.

Intimate Association a Help

But if the selfish child is too old for the Kindergarten, he should

belong to a club. Consistent selfishness will not long be tolerated

here. The tacit or outspoken rebuke of his mates has many times the force of a

domestic rebuke; because thereby he sees himself, at least for a time, as his

comrades see him, and never thereafter entirely loses his suspicion that they

may be right. Their individual judgment he may defy, but their collective

judgment has in it an almost magical power, and convinces him in spite of

himself.

Cultivate Affections

Whatever strong affections the selfish boy shows most be carefully

cultivated. Love for another is the only sure cure for selfishness. If he loves

animals, let him have pets, and give into his hands the whole responsibility

for the care of them. It is better to let the poor animals suffer some neglect,

than to take away from the boy the responsibility for their condition. They

serve him only so far as he can be induced to serve them. The chief rule for

the cure of selfishness is, then, to watch every affection, small and large,

encourage it, give it room to grow, and see to it that the child does not

merely get delight out of it, but that he works for it, that he sacrifices

himself for those whom he loves.

LAZINESS.

The Physical Cause

This condition is often normal, especially during adolescence. The

developing boy or girl wants to lop and to lounge, to lie sprawled over the

floor or the sofa. Quick movement is distasteful to him, and often has an undue

effect upon the heart's action. He is normally dreamy, languid, indifferent,

and subject to various moods. These things are merely tokens of the tremendous

change that is going on within his organism, and which heavily drains his

vitality. Certain duties may, of course, be required of him at this stage, but

they should be light and steady. He should not be expected to fill up chinks

and run errands with joyful alacrity. The six- or eight-year-old may be called

upon for these things, and not he harmed, but this is not true of the child

between twelve and seventeen. He has absorbing business on hand and should not

be too often called away from it.

Laziness and Rapid Growth

Laziness ordinarily accompanies rapid growth of any kind. The unusually

large child, even if he has not yet reached the period of adolescence, is

likely to be lazy. His nervous energies are deflected to keep up his growth,

and his intelligence is often temporarily dulled by the rapidity of his

increase in size.

Hurry Not Natural

Moreover, it is not natural for any child to hurry. Hurry is in itself both

a result of nervous strain and a cause of it; and grown people whose nerves

have been permanently wrenched away from normal quietude and steadiness, often

form a habit of hurry which makes them both unfriendly toward children and very

bad for children. These young creatures ought to go along through their days

rather dreamily and altogether serenely. Every turn of the screw to tighten

their nerves makes more certain some form of early nervous breakdown. They

ought to have work to do, of course,—enough of it to occupy both mind and

body—but it should be quiet, systematic, regular work, much of it

performed automatically. Only occasionally should they be required to do things

with a conscious effort to attain speed.

Abnormal Laziness

However, there is a degree of laziness difficult of definition which is

abnormal; the child fails to perform any work with regularity, and falls behind

both at school and at home. This may be the result of (1) poor

assimilation, (2) of anaemia, or it may be (3) the first symptom

of some disease.

(1.) Poor assimilation may show itself either by (a) thinness and lack of

appetite; (b) fat and abnormal appetite; (c) retarded growth; or (d) irregular

and poorly made teeth and weak bones.

Anaemia

(2.) Anaemia betrays itself most characteristically by the color of the lips

and gums. These, instead of being red, are a pale yellowish pink, and the whole

complexion has a sort of waxy pallor. In extreme cases this pallor even becomes

greenish. As the disease is accompanied with little pain, and few if any marked

symptoms, beyond sleepiness and weakness, it often exists for some time without

being suspected by the parents.

(3.) The advent of many other diseases is announced by a languid

indifference to surroundings, and a slow response to the customary stimuli. The

child's brain seems clouded, and a light form of torpor invades the whole body.

The child, who is usually active and interested in things about him, but who

loses his activity and becomes dull and irresponsive, should be carefully

watched. It may be that he is merely changing his form of

growth—i.e., is beginning to grow tall after completion of his

period of laying on flesh, or vice versa. Or he may be entering upon the period

of adolescence. But if it is neither of these things, a physician should be

consulted.

Monotony

A milder degree of laziness may be induced by a too monotonous round of

duties. Try changing them. Make them as attractive as possible. For, of course,

you do not require him to perform these duties for your sake, whatever you

allow him to suppose about it, but chiefly for the sake of their influence on

his character. Therefore, if the influence of any work is bad, you will change

it, although the new work may not be nearly so much what you prefer to have him

do. Whatever the work is, if it is only emptying waste-baskets, don't nag him,

merely expect him to do it, and expect it steadily.

Helping

In their earlier years all children love to help mother. They like any piece

of real work even better than play. If this love of activity was properly

encouraged, if the mother permitted the child to help, even when he succeeded

only in hindering, he might well become one those fortunate persons who love to

work. This is the real time for preventing laziness. But if this early period

has been missed, the next best thing is to take advantage of every spontaneous

interest as it arises; to hitch the impulse, as it were, to some task that must

be steadily performed. For example, if the child wants to play with tools, help

him to make a small water-wheel, or any other interesting contrivance, and keep

him at it by various devices until he has brought it to a fair degree of

completion Your aim is to stretch his will each time he attempts to do

something a little further than it tends to go of itself; to let him work a

little past his first impulse, so that he may learn by degrees to work when

work is needed, and not only when he feels like it.

UNTIDINESS.

Neatness Not Natural

Essentially a fault of immaturity as this is, we must beware how we measure

it by a too severe adult standard. It is not natural for any young creature to

take an interest in cleanliness. Even the young animals are cared for in this

respect by their parents; the cow licks her calf; the cat, her kittens; and

neither calf nor kittens seem to take much interest in the process. The

conscious love of cleanliness and order grows with years, and seems to be

largely a matter of custom. The child who has always lived in decent

surroundings by-and-by finds them necessary to his comfort, and is willing to

make a degree of effort to secure them. On the contrary, the street boy who

sleeps in his clothes, does not know what it is to desire a well-made bed, and

an orderly room.

Remedies

Example

Habit