This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

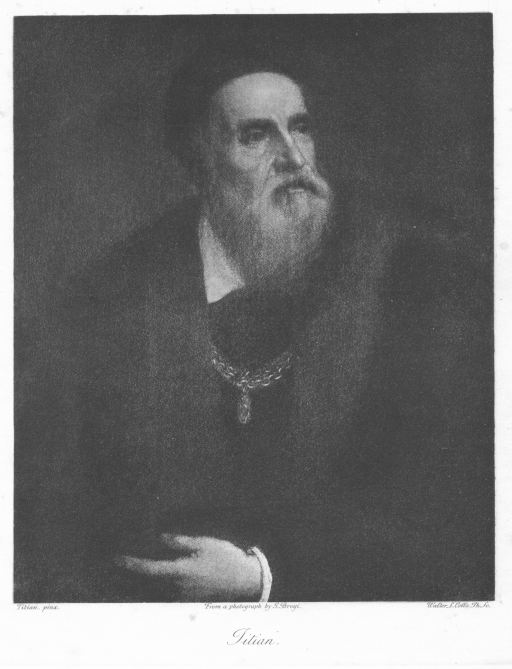

Title: The Later works of Titian

Author: Claude Phillips

Release Date: June 19, 2004 [eBook #12657]

Language: English

Character set encoding: iso-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LATER WORKS OF TITIAN***

COPPER PLATES

ILLUSTRATIONS PRINTED IN SEPIA

ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

Having followed Titian as far as the year 1530, rendered memorable by that sensational, and, of its kind, triumphant achievement, The Martyrdom of St. Peter the Dominican, we must retrace our steps some three years in order to dwell a little upon an incident which must appear of vital importance to those who seek to understand Titian's life, and, above all, to follow the development of his art during the middle period of splendid maturity reaching to the confines of old age. This incident is the meeting with Pietro Aretino at Venice in 1527, and the gradual strengthening by mutual service and mutual inclination of the bonds of a friendship which is to endure without break until the life of the Aretine comes, many years later, to a sudden and violent end. Titian was at that time fifty years of age, and he might thus be deemed to have over-passed the age of sensuous delights. Yet it must be remembered that he was in the fullest vigour of manhood, and had only then arrived at the middle point of a career which, in its untroubled serenity, was to endure for a full half-century more, less a single year. Three years later on, that is to say in the middle of August 1530, the death of his wife Cecilia, who had borne to him Pomponio, Orazio, and Lavinia, left him all disconsolate, and so embarrassed with the cares of his young family that he was compelled to appeal to his sister Orsa, who thereupon came from Cadore to preside over his household. The highest point of celebrity, of favour with princes and magnates, having been attained, and a certain royalty in Venetian art being already conceded to him, there was no longer any obstacle to the organising of a life in which all the refinements of culture and all the delights of sense were to form the most agreeable relief to days of continuous and magnificently fruitful labour. It is just because Titian's art of this great period of some twenty years so entirely accords with what we know, and may legitimately infer, to have been his life at this time, that it becomes important to consider the friendship with Aretino and the rise of the so-called Triumvirate, which was a kind of Council of Three, having as its raison d'être the mutual furtherance of material interests, and the pursuit of art, love, and pleasure. The third member of the Triumvirate was Jacopo Tatti or del Sansovino, the Florentine sculptor, whose fame and fortune were so far above his deserts as an artist. Coming to Venice after the sack of Rome, which so entirely for the moment disorganised art and artists in the pontifical city, he elected to remain there notwithstanding the pressing invitations sent to him by Francis the First to take service with him. In 1529 he was appointed architect of San Marco, and he then by his adhesion completed the Triumvirate which was to endure for more than a quarter of a century.

It has always excited a certain sense of distrust in Titian, and caused the world to form a lower estimate of his character than it would otherwise have done, that he should have been capable of thus living in the closest and most fraternal intimacy with a man so spotted and in many ways so infamous as Aretino. Without precisely calling Titian to account in set terms, his biographers Crowe and Cavalcaselle, and above all M. Georges Lafenestre in La Vie et L'Oeuvre du Titien, have relentlessly raked up Aretino's past before he came together with the Cadorine, and as pitilessly laid bare that organised system of professional sycophancy, adulation, scurrilous libel, and blackmail, which was the foundation and the backbone of his life of outward pomp and luxurious ease at Venice. By them, as by his other biographers, he has been judged, not indeed unjustly, yet perhaps too much from the standard of our own time, too little from that of his own. With all his infamies, Aretino was a man whom sovereigns and princes, nay even pontiffs, delighted to honour, or rather to distinguish by honours. The Marquess Federigo Gonzaga of Mantua, the Duke Guidobaldo II. of Urbino, among many others, showed themselves ready to propitiate him; and such a man as Titian the worldly-wise, the lover of splendid living to whom ample means and the fruitful favour of the great were a necessity; who was grasping yet not avaricious, who loved wealth chiefly because it secured material consideration and a life of serene enjoyment; such a man could not be expected to rise superior to the temptations presented by a friendship with Aretino, or to despise the immense advantages which it included. As he is revealed by his biographers, and above all by himself, Aretino was essentially "good company." He could pass off his most flagrant misdeeds, his worst sallies, with a certain large and Rabelaisian gaiety; if he made money his chief god, it was to spend it in magnificent clothes and high living, but also at times with an intelligent and even a beneficent liberality. He was a fine though not an unerring connoisseur of art, he had a passionate love of music, and an unusually exquisite perception of the beauties of Nature.

To hint that the lower nature of the man corrupted that of Titian, and exercised a disintegrating influence over his art, would be to go far beyond the requirements of the case. The great Venetian, though he might at this stage be much nearer to earth than in those early days when he was enveloped in the golden glow of Giorgione's overmastering influence, could never have lowered himself to the level of those too famous Sonetti Lussuriosi which brought down the vengeance of even a Medici Pope (Clement VII.) upon Aretino the writer, Giulio Romano the illustrator, and Marcantonio Raimondi the engraver. Gracious and dignified in sensuousness he always remained even when, as at this middle stage of his career, the vivifying shafts of poetry no longer pierced through, and transmuted with their vibration of true passion, the fair realities of life. He could never have been guilty of the frigid and calculated indecency of a Giulio Romano; he could not have cast aside all conventional restraints, of taste as well as of propriety, as Rubens and even Rembrandt did on occasion; but as Van Dyck, the child of Titian almost as much as he was the child of Rubens, ever shrank from doing. Still the ease and splendour of the life at Biri Grande—that pleasant abode with its fair gardens overlooking Murano, the Lagoons, and the Friulan Alps, to which Titian migrated in 1531—the Epicureanism which saturated the atmosphere, the necessity for keeping constantly in view the material side of life, all these things operated to colour the creations which mark this period of Titian's practice, at which he has reached the apex of pictorial achievement, but shows himself too serene in sensuousness, too unruffled in the masterly practice of his profession to give to the heart the absolute satisfaction that he affords to the eyes. This is the greatest test of genius of the first order—to preserve undimmed in mature manhood and old age the gift of imaginative interpretation which youth and love give, or lend, to so many who, buoyed up by momentary inspiration, are yet not to remain permanently in the first rank. With Titian at this time supreme ability is not invariably illumined from within by the lamp of genius; the light flashes forth nevertheless, now and again, and most often in those portraits of men of which the sublime Charles V. at Mühlberg is the greatest. Towards the end the flame will rise once more and steadily burn, with something on occasion of the old heat, but with a hue paler and more mysterious, such as may naturally be the outward symbol of genius on the confines of eternity.

The second period, following upon the completion of the St. Peter Martyr, is one less of great altar-pieces and poesie such as the miscalled Sacred and Profane Love (Medea and Venus), the Bacchanals, and the Bacchus and Ariadne, than it is of splendid nudities and great portraits. In the former, however mythological be the subject, it is generally chosen but to afford a decent pretext for the generous display of beauty unveiled. The portraits are at this stage less often intimate and soul-searching in their summing up of a human personality than they are official presentments of great personages and noble dames; showing them, no doubt, without false adulation or cheap idealisation, yet much as they desire to appear to their allies, their friends, and their subjects, sovereign in natural dignity and aristocratic grace, yet essentially in a moment of representation. Farther on the great altar-pieces reappear more sombre, more agitated in passion, as befits the period of the sixteenth century in which Titian's latest years are passed, and the patrons for whom he paints. Of the poesie there is then a new upspringing, a new efflorescence, and we get by the side of the Venus and Adonis, the Diana and Actæon, the Diana and Calisto, the Rape of Europa, such pieces of a more exquisite and penetrating poetry as the Venere del Pardo of Paris, and the Nymph and Shepherd of Vienna.

This appears to be the right place to say a word about the magnificent engraving by Van Dalen of a portrait, no longer known to exist, but which has, upon the evidence apparently of the print, been put down as that of Titian by himself. It represents a bearded man of some thirty-five years, dressed in a rich but sombre habit, and holding a book. The portrait is evidently not that of a painter by himself, nor does it represent Titian at any age; but it finely suggests, even in black and white, a noble original by the master. Now, a comparison with the best authenticated portrait of Aretino, the superb three-quarter length painted in 1545, and actually at the Pitti Palace, reveals certain marked similarities of feature and type, notwithstanding the very considerable difference of age between the personages represented. Very striking is the agreement of eye and nose in either case, while in the younger as in the older man we note an idiosyncrasy in which vigorous intellect as well as strong sensuality has full play. Van Dalen's engraving very probably reproduces one of the lost portraits of Aretino by Titian. In Crowe and Cavalcaselle's Biography (vol. i. pp. 317-319) we learn from correspondence interchanged in the summer of 1527 between Federigo Gonzaga, Titian, and Aretino, that the painter, in order to propitiate the Mantuan ruler, sent to him with a letter, the exaggerated flattery of which savours of Aretino's precept and example, portraits of the latter and of Signor Hieronimo Adorno, another "faithful servant" of the Marquess. Now Aretino was born in 1492, so that in 1527 he would be thirty-five, which appears to be just about the age of the vigorous and splendid personage in Van Dalen's print.

Some reasons were given in the former section of this monograph[1] for the assertion that the Madonna with St. Catherine, mentioned in a letter from Giacomo Malatesta to the Marchese Federigo Gonzaga, dated February 1530, was not, as is assumed by Crowe and Cavalcaselle, the Madonna del Coniglio of the Louvre, but the Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist and St. Catherine, which is No. 635 at the National Gallery.[2] Few pictures of the master have been more frequently copied and adapted than this radiantly beautiful piece, in which the dominant chord of the scheme of colour is composed by the cerulean blues of the heavens and the Virgin's entire dress, the deep luscious greens of the landscape, and the peculiar, pale, citron hue, relieved with a crimson girdle, of the robe worn by the St. Catherine, a splendid Venetian beauty of no very refined type or emotional intensity. Perfect repose and serenity are the keynote of the conception, which in its luxuriant beauty has little of the power to touch that must be conceded to the more naïve and equally splendid Madonna del Coniglio.[3] It is above all in the wonderful Venetian landscape—a mountain-bordered vale, along which flocks and herds are being driven, under a sky of the most intense blue—that the master shows himself supreme. Nature is therein not so much detailed as synthesised with a sweeping breadth which makes of the scene not the reflection of one beautiful spot in the Venetian territory, but without loss of essential truth or character a very type of Venetian landscape of the sixteenth century. These herdsmen and their flocks, and also the note of warning in the sky of supernatural splendour, recall the beautiful Venetian storm-landscape in the royal collection at Buckingham Palace. This has been very generally attributed to Titian himself,[4] and described as the only canvas still extant in which he has made landscape his one and only theme. It has, indeed, a rare and mysterious power to move, a true poetry of interpretation. A fleeting moment, full of portent as well as of beauty, has been seized; the smile traversed by a frown of the stormy sky, half overshadowing half revealing the wooded slopes, the rich plain, and the distant mountains, is rendered with a rare felicity. The beauty is, all the same, in the conception and in the thing actually seen—much less in the actual painting. It is hardly possible to convince oneself, comparing the work with such landscape backgrounds as those in this picture at the National Gallery in the somewhat earlier Madonna del Coniglio, and the gigantic St. Peter Martyr, or, indeed, in a score of other genuine productions, that the depth, the vigour, the authority of Titian himself are here to be recognised. The weak treatment of the great Titianesque tree in the foreground, with its too summarily indicated foliage—to select only one detail that comes naturally to hand—would in itself suffice to bring such an attribution into question.

Vasari states, speaking confessedly from hearsay, that in 1530, the Emperor Charles V. being at Bologna, Titian was summoned thither by Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici, using Aretino as an intermediary, and that he on that occasion executed a most admirable portrait of His Majesty, all in arms, which had so much success that the artist received as a present a thousand scudi. Crowe and Cavalcaselle, however, adduce strong evidence to prove that Titian was busy in Venice for Federigo Gonzaga at the time of the Emperor's first visit, and that he only proceeded to Bologna in July to paint for the Marquess of Mantua the portrait of a Bolognese beauty, La Cornelia, the lady-in-waiting of the Countess Pepoli, whom Covas, the all-powerful political secretary of Charles the Fifth, had seen and admired at the splendid entertainments given by the Pepoli to the Emperor. Vasari has in all probability confounded this journey of Charles in 1530 with that subsequent one undertaken in 1532 when Titian not only portrayed the Emperor, but also painted an admirable likeness of Ippolito de' Medici presently to be described. He had the bad luck on this occasion to miss the lady Cornelia, who had retired to Nuvolara, indisposed and not in good face. The letter written by our painter to the Marquess in connection with this incident[5] is chiefly remarkable as affording evidence of his too great anxiety to portray the lady without approaching her, relying merely on the portrait, "che fece quel altro pittore della detta Cornelia"; of his unwillingness to proceed to Nuvolara, unless the picture thus done at second hand should require alteration. In truth we have lighted here upon one of Titian's most besetting sins, this willingness, this eagerness, when occasion offers, to paint portraits without direct reference to the model. In this connection we are reminded that he never saw Francis the First, whose likeness he notwithstanding painted with so showy and superficial a magnificence as to make up to the casual observer for the absence of true vitality;[6] that the Empress Isabella, Charles V.'s consort, when at the behest of the monarch he produced her sumptuous but lifeless and empty portrait, now in the great gallery of the Prado, was long since dead. He consented, basing his picture upon a likeness of much earlier date, to paint Isabella d'Este Gonzaga as a young woman when she was already an old one, thereby flattering an amiable and natural weakness in this great princess and unrivalled dilettante, but impairing his own position as an artist of supreme rank.[7] It is not necessary to include in this category the popular Caterina Cornaro of the Uffizi, since it is confessedly nothing but a fancy portrait, making no reference to the true aspect at any period of the long-since deceased queen of Cyprus, and, what is more, no original Titian, but at the utmost an atelier piece from his entourage. Take, however, as an instance the Francis the First, which was painted some few years later than the time at which we have now arrived, and at about the same period as the Isabella d'Este. Though as a portrait d'apparat it makes its effect, and reveals the sovereign accomplishment of the master, does it not shrink into the merest insignificance when compared with such renderings from life as the successive portraits of Charles the Fifth, the Ippolito de' Medici, the Francesco Maria della Rovere? This is as it must and should be, and Titian is not the less great, but the greater, because he cannot convincingly evolve at second hand the true human individuality, physical and mental, of man or woman.

It was in the earlier part of 1531 that Titian painted for Federigo Gonzaga a St. Jerome and a St. Mary Magdalene, destined for the famous Vittoria Colonna, Marchioness of Pescara, who had expressed to the ruler of Mantua the desire to possess such a picture. Gonzaga writes to the Marchioness on March 11, 1831[8]:—"Ho subito mandate a Venezia e scritto a Titiano, quale è forse il piu eccellente in quell' arte che a nostri tempi si ritrovi, ed è tutto mio, ricercandolo con grande instantia a volerne fare una bella lagrimosa piu che si so puo, e farmela haver presto." The passage is worth quoting as showing the estimation in which Titian was held at a court which had known and still knew the greatest Italian masters of the art.

It is not possible at present to identify with any extant painting the St. Jerome, of which we know that it hung in the private apartments of the Marchioness Isabella at Mantua. The writer is unable to accept Crowe and Cavalcaselle's suggestion that it may be the fine moonlight landscape with St. Jerome in prayer which is now in the Long Gallery of the Louvre. This piece, if indeed it be by Titian, which is by no means certain, must belong to his late time. The landscape, which is marked by a beautiful and wholly unconventional treatment of moonlight, for which it would not be easy to find a parallel in the painting of the time, is worthy of the Cadorine, and agrees well, especially in the broad treatment of foliage, with, for instance, the background in the late Venus and Cupid of the Tribuna.[9] The figure of St. Jerome, on the other hand, does not in the peculiar tightness of the modelling, or in the flesh-tints, recall Titian's masterly synthetic way of going to work in works of this late period. The noble St. Jerome of the Brera, which indubitably belongs to a well-advanced stage in the late time, will be dealt with in its right place. Though it does not appear probable that we have, in the much-admired Magdalen of the Pitti, the picture here referred to—this last having belonged to Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, and representing, to judge by style, a somewhat more advanced period in the painter's career—it may be convenient to mention it here. As an example of accomplished brush-work, of handling careful and yet splendid in breadth, it is indeed worthy of all admiration. The colours of the fair human body, the marvellous wealth of golden blond hair, the youthful flesh glowing semi-transparent, and suggesting the rush of the blood beneath; these are also the colours of the picture, aided only by the indefinite landscape and the deep blue sky of the background. If this were to be accepted as the Magdalen painted for Federigo Gonzaga, we must hold, nevertheless, that Titian with his masterpiece of painting only half satisfied the requirements of his patron. Bellissima this Magdalen undoubtedly is, but hardly lagrimosa pin che si puo. She is a belle pécheresse whose repentance sits all too lightly upon her, whose consciousness of a physical charm not easily to be withstood is hardly disguised. Somehow, although the picture in no way oversteps the bounds of decency, and cannot be objected to even by the most over-scrupulous, there is latent in it a jarring note of unrefinement in the presentment of exuberant youth and beauty which we do not find in the more avowedly sensuous Venus of the Tribuna. This last is an avowed act of worship by the artist of the naked human body, and as such, in its noble frankness, free from all offence, except to those whose scruples in matters of art we are not here called upon to consider. From this Magdalen to that much later one of the Hermitage, which will be described farther on, is a great step upwards, and it is a step which, in passing from the middle to the last period, we shall more than once find ourselves taking.

It is impossible to give even in outline here an account of Titian's correspondence and business relations with his noble and royal patrons, instructive as it is to follow these out, and to see how, under the influence of Aretino, his natural eagerness to grasp in every direction at material advantages is sharpened; how he becomes at once more humble and more pressing, covering with the manner and the tone appropriate to courts the reiterated demands of the keen and indefatigable man of business. It is the less necessary to attempt any such account in these pages—dealing as we are chiefly with the work and not primarily with the life of Titian—seeing that in Crowe and Cavalcaselle's admirable biography this side of the subject, among many others, is most patiently and exhaustively dealt with.

In 1531 we read of a Boy Baptist by Titian sent by Aretino to Maximian Stampa, an imperialist partisan in command of the castle of Milan. The donor particularly dwells upon "the beautiful curl of the Baptist's hair, the fairness of his skin, etc.," a description which recalls to us, in striking fashion, the little St. John in the Virgin and Child with St. Catherine of the National Gallery, which belongs, as has been shown, to the same time.

It was on the occasion of the second visit of the Emperor and his court to Bologna at the close of 1532 that Titian first came in personal contact with Charles V., and obtained from that monarch his first sitting. In the course of an inspection, with Federigo Gonzaga himself as cicerone, of the art treasures preserved in the palace at Mantua, the Emperor saw the portrait by Titian of Federigo, and was so much struck with it, so intent upon obtaining a portrait of himself from the same brush, that the Marquess wrote off at once pressing our master to join him without delay in his capital. Titian preferred, however, to go direct to Bologna in the train of his earlier patron Alfonso d'Este. It was on this occasion that Charles's all-powerful secretary, the greedy, overbearing Covos, exacted as a gift from the agents of the Duke of Ferrara, among other things, a portrait of Alfonso himself by Titian; and in all probability obtained also a portrait from the same hand of Ercole d'Este, the heir-apparent. There is evidence to show that the portrait of Alfonso was at once handed over to, or appropriated by, the Emperor.

Whether this was the picture described by Vasari as representing the prince with his arm resting on a great piece of artillery, does not appear. Of this last a copy exists in the Pitti Gallery which Crowe and Cavalcaselle have ascribed to Dosso Dossi, but the original is nowhere to be traced. The Ferrarese ruler is, in this last canvas, depicted as a man of forty or upwards, of resolute and somewhat careworn aspect. It has already been demonstrated, on evidence furnished by Herr Carl Justi, that the supposed portrait of Alfonso, in the gallery of the Prado at Madrid, cannot possibly represent Titian's patron at any stage of his career, but in all probability, like the so-called Giorgio Cornaro of Castle Howard, is a likeness of his son and successor, Ercole II.

Titian's first portrait of the Emperor, a full-length in which he appeared in armour with a generalissimo's baton of command, was taken in 1556 from Brussels to Madrid, after the formal ceremony of abdication, and perished, it would appear, in one of the too numerous fires which have devastated from time to time the royal palaces of the Spanish capital and its neighbourhood. To the same period belongs, no doubt, the noble full-length of Charles in gala court costume which now hangs in the Sala de la Reina Isabel in the Prado Gallery, as a pendant to Titian's portrait of Philip II. in youth. Crowe and Cavalcaselle assume that not this picture, but a replica, was the one which found its way into Charles I.'s collection, and was there catalogued by Van der Doort as "the Emperor Charles the Fifth, brought by the king from Spain, being done at length with a big white Irish dog"—going afterwards, at the dispersal of the king's effects, to Sir Balthasar Gerbier for £150. There is, however, no valid reason for doubting that this is the very picture owned for a time by Charles I., and which busy intriguing Gerbier afterwards bought, only to part with it to Cardenas the Spanish ambassador.[10] Other famous originals by Titian were among the choicest gifts made by Philip IV. to Prince Charles at the time of his runaway expedition to Madrid with the Duke of Buckingham, and this was no doubt among them. Confirmation is supplied by the fact that the references to the existence of this picture in the royal palaces of Madrid are for the reigns of Philip II., Charles II., and Charles III., thus leaving a large gap unaccounted for. Dimmed as the great portrait is, robbed of its glow and its chastened splendour in a variety of ways, it is still a rare example of the master's unequalled power in rendering race, the unaffected consciousness of exalted rank, natural as distinguished from assumed dignity. There is here no demonstrative assertion of grandeza, no menacing display of truculent authority, but an absolutely serene and simple attitude such as can only be the outcome of a consciousness of supreme rank and responsibility which it can never have occurred to any one to call into question. To see and perpetuate these subtle qualities, which go so far to redeem the physical drawbacks of the House of Hapsburg, the painter must have had a peculiar instinct for what is aristocratic in the higher sense of the word—that is, both outwardly and inwardly distinguished. This was indeed one of the leading characteristics of Titian's great art, more especially in portraiture. Giorgione went deeper, knowing the secret of the soul's refinement, the aristocracy of poetry and passion; Lotto sympathetically laid bare the heart's secrets and showed the pathetic helplessness of humanity. Tintoretto communicated his own savage grandeur, his own unrest, to those whom he depicted; Paolo Veronese charmed without arrière-pensée by the intensity of vitality which with perfect simplicity he preserved in his sitters. Yet to Titian must be conceded absolute supremacy in the rendering not only of the outward but of the essential dignity, the refinement of type and bearing, which without doubt come unconsciously to those who can boast a noble and illustrious ancestry.

Again the writer hesitates to agree with Crowe and Cavalcaselle when they place at this period, that is to say about 1533, the superb Allegory of the Louvre (No. 1589), which is very generally believed to represent the famous commander Alfonso d'Avalos, Marqués del Vasto, with his family. The eminent biographers of Titian connect the picture with the return of d'Avalos from the campaign against the Turks, undertaken by him in the autumn of 1532, under the leadership of Croy, at the behest of his imperial master. They hazard the surmise that the picture, though painted after Alfonso's return, symbolises his departure for the wars, "consoled by Victory, Love, and Hymen." A more natural conclusion would surely be that what Titian has sought to suggest is the return of the commander to enjoy the hard-earned fruits of victory.

The Italo-Spanish grandee was born at Naples in 1502, so that at this date he would have been but thirty-one years of age, whereas the mailed warrior of the Allegory is at least forty, perhaps older. Moreover, and this is the essential point, the technical qualities of the picture, the wonderful easy mastery of the handling, the peculiarities of the colouring and the general tone, surely point to a rather later date, to a period, indeed, some ten years ahead of the time at which we have arrived. If we are to accept the tradition that this Allegory, or quasi-allegorical portrait-piece, giving a fanciful embodiment to the pleasures of martial domination, of conjugal love, of well-earned peace and plenty, represents d'Avalos, his consort Mary of Arragon, and their family—and a comparison with the well-authenticated portrait of Del Vasto in the Allocution of Madrid does not carry with it entire conviction—we must perforce place the Louvre picture some ten years later than do Crowe and Cavalcaselle. Apart from the question of identification, it appears to the writer that the technical execution of the piece would lead to a similar conclusion.[11]

To this year, 1533, belongs one of the masterpieces in portraiture of our painter, the wonderful Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici in a Hungarian habit of the Pitti. This youthful Prince of the Church, the natural son of Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours, was born in 1511, so that when Titian so incomparably portrayed him, he was, for all the perfect maturity of his virile beauty, for all the perfect self-possession of his aspect, but twenty-two years of age. He was the passionate worshipper of the divine Giulia Gonzaga, whose portrait he caused to be painted by Sebastiano del Piombo. His part in the war undertaken by Charles V. in 1532, against the Turks, had been a strange one. Clement VII., his relative, had appointed him Legate and sent him to Vienna at the head of three hundred musketeers. But when Charles withdrew from the army to return to Italy, the Italian contingent, instead of going in pursuit of the Sultan into Hungary, opportunely mutinied, thus affording to their pleasure-loving leader the desired pretext for riding back with them through the Austrian provinces, with eyes wilfully closed the while to their acts of depredation. It was in the rich and fantastic habit of a Hungarian captain that the handsome young Medici was now painted by Titian at Bologna, the result being a portrait unique of its kind even in his life-work. The sombre glow of the supple, youthful flesh, the red-brown of the rich velvet habit which defines the perfect shape of Ippolito, the red of the fantastic plumed head-dress worn by him with such sovereign ease, make up a deep harmony, warm, yet not in the technical sense hot, and of indescribable effect. And this effect is centralised in the uncanny glance, the mysterious aspect of the man whom, as we see him here, a woman might love for his beauty, but a man would do well to distrust. The smaller portrait painted by Titian about the same time of the young Cardinal fully armed—the one which, with the Pitti picture, Vasari saw in the closet (guardaroba) of Cosimo, Duke of Tuscany—is not now known to exist.[12]

It may be convenient to mention here one of the most magnificent among the male portraits of Titian, the Young Nobleman in the Sala di Marte of the Pitti Gallery, although its exact place in the middle time of the artist it is, failing all data on the point, not easy to determine. At Florence there has somehow been attached to it the curious name Howard duca di Norfolk,[13] but upon what grounds, if any, the writer is unable to state. The master of Cadore never painted a head more finely or with a more exquisite finesse, never more happily characterised a face, than that of this resolute, self-contained young patrician with the curly chestnut hair and the short, fine beard and moustache—a personage high of rank, doubtless, notwithstanding the studied simplicity of his dress. Because we know nothing of the sitter, and there is in his pose and general aspect nothing sensational, this masterpiece is, if not precisely not less celebrated among connoisseurs, at any rate less popular with the larger public, than it deserves to be.[14]

The noble altar-piece in the church of S. Giovanni Elemosinario at Venice showing the saint of that name enthroned, and giving alms to a beggar, belongs to the close of 1533 or thereabouts, since the high-altar was finished in the month of October of that year. According to Vasari, it must be regarded as having served above all to assert once for all the supremacy of Titian over Pordenone, whose friends had obtained for him the commission to paint in competition with the Cadorine an altar-piece for one of the apsidal chapels of the church, where, indeed, his work is still to be seen.[15] Titian's canvas, like most of the great altar-pieces of the middle time, was originally arched at the top; but the vandalism of a subsequent epoch has, as in the case of the Madonna di S. Niccola, now in the Vatican, made of this arch a square, thereby greatly impairing the majesty of the general effect. Titian here solves the problem of combining the strong and simple decorative aspect demanded by the position of the work as the central feature of a small church, with the utmost pathos and dignity, thus doing incomparably in his own way—the way of the colourist and the warm, the essentially human realist—what Michelangelo had, soaring high above earth, accomplished with unapproachable sublimity in the Prophets and Sibyls of the Sixtine Chapel.

The colour is appropriately sober, yet a general tone is produced of great strength and astonishing effectiveness. The illumination is that of the open air, tempered and modified by an overhanging canopy of green; the great effect is obtained by the brilliant grayish white of the saint's alb, dominating and keeping in due balance the red of the rochet and the under-robes, the cloud-veiled sky, the marble throne or podium, the dark green hanging. This picture must have had in the years to follow a strong and lasting influence on Paolo Veronese, the keynote to whose audaciously brilliant yet never over-dazzling colour is this use of white and gray in large dominating masses. The noble figure of S. Giovanni gave him a prototype for many of his imposing figures of bearded old men. There is a strong reminiscence, too, of the saint's attitude in one of the most wonderful of extant Veroneses—that sumptuous altar-piece SS. Anthony, Cornelius, and Cyprian with a Page, in the Brera, for which he invented a harmony as delicious as it is daring, composed wholly of violet-purple, green, and gold.

Within the years 1532 and 1538, or thereabouts, would appear to fall Titian's relations with another princely patron, Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, the nephew of the redoubtable Pope Julius II., whose qualities of martial ardour and unbridled passion he reproduced in an exaggerated form. By his mother, Giovanna da Montefeltro, he descended also from the rightful dynasty of Urbino, to which he succeeded in virtue of adoption. His life of perpetual strife, of warfare in defence of his more than once lost and reconquered duchy, and as the captain first of the army of the Church, afterwards of the Venetian forces, came to an abrupt end in 1538. With his own hand he had, in the ardent days of his youth, slain in the open streets of Ravenna the handsome, sinister Cardinal Alidosi, thereby bringing down upon himself the anathemas of his uncle, Julius II., and furnishing to his successor, the Medici pope Leo X., the best possible excuse for the sequestration of the duchy of Urbino in favour of his own house. He himself died by poison, suspicion resting upon the infamous Pier Luigi Farnese, the son of Paul III.

Francesco Maria had espoused Eleonora Gonzaga, the sister of Titian's protector, Federigo, and it is probably through the latter that the relations with our master sprang up to which we owe a small group of his very finest works, including the so-called Venus of Urbino of the Tribuna, the Girl in a Fur Cloak of the Vienna Gallery, and the companion portraits of Francesco Maria and Eleonora which are now in the Venetian Gallery at the Uffizi. The fiery leader of armies had, it should be remembered, been brought up by Guidobaldo of Montefeltro, one of the most amiable and enlightened princes of his time, and, moreover, his consort Eleonora was the daughter of Isabella d'Este Gonzaga, than whom the Renaissance knew no more enthusiastic or more discriminating patron of art.

A curious problem meets us at the outset. We may assume with some degree of certainty that the portraits of the duke and duchess belong to the year 1537. Stylistic characteristics point to the conclusion that the great Venus of the Tribuna, the so-called Bella di Tiziano, and the Girl in the Fur Cloak—to take only undoubted originals—belong to much the same stage of Titian's practice as the companion portraits at the Uffizi. Eleonora Gonzaga, a princess of the highest culture, the daughter of an admirable mother, the friend of Pietro Bembo, Sadolet, and Baldassarre Castiglione, was at this time a matron of some twenty years' standing; at the date when her avowed portrait was painted she must have been at the very least forty. By what magic did Titian manage to suggest her type and physiognomy in the famous pictures just now mentioned, and yet to plunge the duchess into a kind of Fontaine de Jouvence, realising in the divine freshness of youth and beauty beings who nevertheless appear to have with her some kind of mystic and unsolved connection? If this was what he really intended—and the results attained may lead us without temerity to assume as much—no subtler or more exquisite form of flattery could be conceived. It is curious to note that at the same time he signally failed with the portrait of her mother, Isabella d'Este, painted in 1534, but showing the Marchioness of Mantua as a young woman of some twenty-five years, though she was then sixty. Here youth and a semblance of beauty are called up by the magic of the artist, but the personality, both physical and mental, is lost in the effort. But then in this last case Titian was working from an early portrait, and without the living original to refer to.

But, before approaching the discussion of the Venus of Urbino, it is necessary to say a word about another Venus which must have been painted some years before this time, revealing, as it does, a completely different and, it must be owned, a higher ideal. This is the terribly ruined, yet still beautiful, Venus Anadyomene, or Venus of the Shell, of the Bridgewater Gallery, painted perhaps at the instigation of some humanist, to realise a description of the world-famous painting of Apelles. It is not at present possible to place this picture with anything approaching to chronological exactitude. It must have been painted some years after the Bacchus and Ariadne of the National Gallery, some years before the Venus of the Tribuna, and that is about as near as surmise can get. The type of the goddess in the Ellesmere picture recalls somewhat the Ariadne in our masterpiece at the National Gallery, but also, albeit in a less material form, the Magdalens of a later time. Titian's conception of perfect womanhood is here midway between his earlier Giorgionesque ideal and the frankly sensuous yet grand luxuriance of his maturity and old age. He never, even in the days of youth and Giorgionesque enchantment, penetrated so far below the surface as did his master and friend Barbarelli. He could not equal him in giving, with the undisguised physical allurement which belongs to the true woman, as distinguished from the ideal conception compounded of womanhood's finest attributes, that sovereignty of amorous yet of spiritual charm which is its complement and its corrective.[16] Still with Titian, too, in the earlier years, woman, as presented in the perfection of mature youth, had, accompanying and elevating her bodily loveliness, a measure of that higher and nobler feminine attractiveness which would enable her to meet man on equal terms, nay, actively to exercise a dominating influence of fascination. In illustration of this assertion it is only necessary to refer to the draped and the undraped figure in the Medea and Venus (Sacred and Profane Love) of the Borghese Gallery, to the Herodias of the Doria Gallery, to the Flora of the Uffizi. Here, even when the beautiful Venetian courtesan is represented or suggested, what the master gives is less the mere votary than the priestess of love. Of this power of domination, this feminine royalty, the Venus Anadyomene still retains a measure, but the Venus of Urbino and the splendid succession of Venuses and Danaës, goddesses, nymphs, and heroines belonging to the period of the fullest maturity, show woman in the phase in which, renouncing her power to enslave, she is herself reduced to slavery.

These glowing presentments of physical attractiveness embody a lower ideal—that of woman as the plaything of man, his precious possession, his delight in the lower sense. And yet Titian expresses this by no means exalted conception with a grand candour, an absence of arrière-pensée such as almost purges it of offence. It is Giovanni Morelli who, in tracing the gradual descent from his recovered treasure, the Venus of Giorgione in the Dresden Gallery,[17] through the various Venuses of Titian down to those of the latest manner, so finely expresses the essential difference between Giorgione's divinity and her sister in the Tribuna. The former sleeping, and protected only by her sovereign loveliness, is safer from offence than the waking goddess—or shall we not rather say woman?—who in Titian's canvas passively waits in her rich Venetian bower, tended by her handmaidens. It is again Morelli[18] who points out that, as compared with Correggio, even Giorgione—to say nothing of Titian—is when he renders the beauty of woman or goddess a realist. And this is true in a sense, yet not altogether. Correggio's Danaë, his Io, his Leda, his Venus, are in their exquisite grace of form and movement farther removed from the mere fleshly beauty of the undraped model than are the goddesses and women of Giorgione. The passion and throb of humanity are replaced by a subtler and less easily explicable charm; beauty becomes a perfectly balanced and finely modulated harmony. Still the allurement is there, and it is more consciously and more provocatively exercised than with Giorgione, though the fascination of Correggio's divinities asserts itself less directly, less candidly. Showing through the frankly human loveliness of Giorgione's women there is after all a higher spirituality, a deeper intimation of that true, that clear-burning passion, enveloping body and soul, which transcends all exterior grace and harmony, however exquisite it may be in refinement of voluptuousness.[19]

It is not, indeed, by any means certain that we are justified in seriously criticising as a Venus the great picture of the Tribuna. Titian himself has given no indication that the beautiful Venetian woman who lies undraped after the bath, while in a sumptuous chamber, furnished according to the mode of the time, her handmaidens are seeking for the robes with which she will adorn herself, is intended to present the love-goddess, or even a beauty masquerading with her attributes. Vasari, who saw it in the picture-closet of the Duke of Urbino, describes it, no doubt, as "une Venere giovanetta a giacere, con fieri e certi panni sottili attorno." It is manifestly borrowed, too—as is now universally acknowledged—from Giorgione's Venus in the Dresden Gallery, with the significant alteration, however, that Titian's fair one voluptuously dreams awake, while Giorgione's goddess more divinely reposes, and sleeping dreams loftier dreams. The motive is in the borrowing robbed of much of its dignity and beauty, and individualised in a fashion which, were any other master than Titian in question, would have brought it to the verge of triviality. Still as an example of his unrivalled mastery in rendering the glow and semi-transparency of flesh, enhanced by the contrast with white linen—itself slightly golden in tinge; in suggesting the appropriate atmospheric environment; in giving the full splendour of Venetian colour, duly subordinated nevertheless to the main motive, which is the glorification of a beautiful human body as it is; in all these respects the picture is of superlative excellence, a representative example of the master and of Venetian art, a piece which it would not be easy to match even among his own works.

More and more, as the supreme artist matures, do we find him disdaining the showier and more evident forms of virtuosity. His colour is more and more marked in its luminous beauty by reticence and concentration, by the search after such a main colour-chord as shall not only be beautiful and satisfying in itself, but expressive of the motive which is at the root of the picture. Play of light over the surfaces and round the contours of the human form; the breaking-up and modulation of masses of colour by that play of light; strength, and beauty of general tone—these are now Titian's main preoccupations. To this point his perfected technical art has legitimately developed itself from the Giorgionesque ideal of colour and tone-harmony, which was essentially the same in principle, though necessarily in a less advanced stage, and more diversified by exceptions. Our master became, as time went on, less and less interested in the mere dexterous juxtaposition of brilliantly harmonising and brilliantly contrasting tints, in piquancy, gaiety, and sparkle of colour, to be achieved for its own sake. Indeed this phase of Venetian sixteenth-century colour belongs rather to those artists who issued from Verona—to the Bonifazi, and to Paolo Veronese—who in this respect, as generally in artistic temperament, proved themselves the natural successors of Domenico and Francesco Morone, of Girolamo dai Libri, of Cavazzola.

Yet when Titian takes colour itself as his chief motive, he can vie with the most sumptuous of them in splendour, and eclipse them all by the sureness of his taste. A good example of this is the celebrated Bella di Tiziano of the Pitti Gallery, another work which, like the Venus of Urbino, recalls the features without giving the precise personality of Eleonora Gonzaga. The beautiful but somewhat expressionless head with its crowning glory of bright hair, a waving mass of Venetian gold, has been so much injured by rubbing down and restoration that we regret what has been lost even more than we enjoy what is left. But the surfaces of the fair and exquisitely modelled neck and bosom have been less cruelly treated; the superb costume retains much of its pristine splendour. With its combination of brownish-purple velvet, peacock-blue brocade, and white lawn, its delicate trimmings of gold, and its further adornment with small knots, having in them, now at any rate, but an effaced note of red, the gown of La Bella has remained the type of what is most beautiful in Venetian costume as it was in the earlier half of the sixteenth century. In richness and ingenious elaboration, chastened by taste, it far transcends the over-splendid and ponderous dresses in which later on the patrician dames portrayed by Veronese and his school loved to array themselves. A bright note of red in the upper jewel of one earring, now, no doubt, cruder than was originally intended, gives a fillip to the whole, after a fashion peculiar to Titian.

The Girl in the Fur Cloak, No 197 in the Imperial Gallery at Vienna, shows once more in a youthful and blooming woman the features of Eleonora. The model is nude under a mantle of black satin lined with fur, which leaves uncovered the right breast and both arms. The picture is undoubtedly Titian's own, and fine in quality, but it reveals less than his usual graciousness and charm. It is probably identical with the canvas described in the often-quoted catalogue of Charles I.'s pictures as "A naked woman putting on her smock, which the king changed with the Duchess of Buckingham for one of His Majesty's Mantua pieces." It may well have suggested to Rubens, who must have seen it among the King's possessions on the occasion of his visit to London, his superb, yet singularly unrefined, Hélène Fourment in a Fur Mantle, now also in the Vienna Gallery.

The great portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino in the Uffizi belong, as has already been noted, to 1537. Francesco Maria, here represented in the penultimate year of his stormy life, assumes deliberately the truculent warrior, and has beyond reasonable doubt made his own pose in a portrait destined to show the leader of armies, and not the amorous spouse or the patron of art and artists. Praise enthusiastic, but not excessive, has ever been and ever will be lavished on the breadth and splendid decision of the painting; on the magnificent rendering of the suit of plain but finely fashioned steel armour, with its wonderful reflections; on the energy of the virile countenance, and the appropriate concentration and simplicity of the whole. The superb head has, it must be confessed, more grandeur and energy than true individuality or life. The companion picture represents Eleonora Gonzaga seated near an open window, wearing a sombre but magnificent costume, and, completing it, one of those turbans with which the patrician ladies of North Italy, other than those of Venice, habitually crowned their locks. It has suffered in loss of freshness and touch more than its companion. Fine and accurate as the portrait is, much as it surpasses its pendant in subtle truth of characterisation, it has in the opinion of the writer been somewhat overpraised. For once, Titian approaches very nearly to the northern ideal in portraiture, underlining the truth with singular accuracy, yet with some sacrifice of graciousness and charm. The daughter of the learned and brilliant Isabella looks here as if, in the decline of her beauty, she had become something of a précieuse and a prude, though it would be imprudent to assert that she was either the one or the other. Perhaps the most attractive feature of the whole composition is the beautiful landscape so characteristically stretching away into the far blue distance, suggested rather than revealed through the open window. This is such a picture as might have inspired the Netherlander Antonio Moro, just because it is Italian art of the Cinquecento with a difference, that is, with a certain admixture of northern downrightness and literalness of statement.

About this same time Titian received from the brother of this princess, his patron and admirer Federigo Gonzaga, the commission for the famous series of the Twelve Cæsars, now only known to the world by stray copies here and there, and by the grotesquely exaggerated engravings of Ægidius Sadeler. Giulio Romano having in 1536[20] completed the Sala di Troja in the Castello of Mantua, and made considerable progress with the apartments round about it, Federigo Gonzaga conceived the idea of devoting one whole room to the painted effigies of the Twelve Cæsars to be undertaken by Titian. The exact date when the Cæsars were delivered is not known, but it may legitimately be inferred that this was in the course of 1537 or the earlier half of 1538. Our master's pictures were, according to Vasari, placed in an anticamera of the Mantuan Palace, below them being hung twelve storie a olio—histories in oils—by Giulio Romano.[21] The Cæsars were all half-lengths, eleven out of the twelve being done by the Venetian master and the twelfth by Giulio Romano himself.[22] Brought to England with the rest of the Mantua pieces purchased by Daniel Nys for Charles I., they suffered injury, and Van Dyck is said to have repainted the Vitellius, which was one of several canvases irretrievably ruined by the quicksilver of the frames during the transit from Italy.[23] On the disposal of the royal collection after Charles Stuart's execution the Twelve Cæsars were sold by the State—not presented, as is usually asserted—to the Spanish Ambassador Cardenas, who gave £1200 for them. On their arrival in Spain with the other treasures secured on behalf of Philip IV., they were placed in the Alcazar of Madrid, where in one of the numerous fires which successively devastated the royal palace they must have perished, since no trace of them is to be found after the end of the seventeenth century. The popularity of Titian's decorative canvases is proved by the fact that Bernardino Campi of Cremona made five successive sets of copies from them—for Charles V., d'Avalos, the Duke of Alva, Rangone, and another Spanish grandee. Agostino Caracci subsequently copied them for the palace of Parma, and traces of yet other copies exist. Numerous versions are shown in private collections, both in England and abroad, purporting to be from the hand of Titian, but of these none—at any rate none of those seen by the writer—are originals or even Venetian copies. Among the best are the examples in the collection of Earl Brownlow and at the royal palace of Munich respectively, and these may possibly be from the hand of Campi. Although we are expressly told in Dolce's Dialogo that Titian "painted the Twelve Cæsars, taking them in part from medals, in part from antique marbles," it is perfectly clear that of the exact copying of antiques—such as is to be noted, for instance, in those marble medallions by Donatello which adorn the courtyard of the Medici Palace at Florence—there can have been no question. The attitudes of the Cæsars, as shown in the engravings and the extant copies, exclude any such supposition. Those who have judged them from those copies and the hideous grotesques of Sadeler have wondered at the popularity of the originals, somewhat hastily deeming Titian to have been here inferior to himself. Strange to say, a better idea of what he intended, and what he may have realised in the originals, is to be obtained from a series of small copies now in the Provincial Museum of Hanover, than from anything else that has survived.[24] The little pictures in question, being on copper, cannot well be anterior to the first part of the seventeenth century, and they are not in themselves wonders. All the same they have a unique interest as proving that, while adopting the pompous attitudes and the purely decorative standpoint which the position of the pictures in the Castello may have rendered obligatory, Titian managed to make of his Emperors creatures of flesh and blood; the splendid Venetian warrior and patrician appearing in all the glory of manhood behind the conventional dignity, the self-consciousness of the Roman type and attitude.

These last years had been to Titian as fruitful in material gain as in honour. He had, as has been seen, established permanent and intimate relations not only with the art-loving rulers of the North Italian principalities, but now with Charles V. himself, mightiest of European sovereigns, and, as a natural consequence, with the all-powerful captains and grandees of the Hispano-Austrian court. Meanwhile a serious danger to his supremacy had arisen. At home in Venice his unique position was threatened by Pordenone, that masterly and wonderfully facile frescante and painter of monumental decorations, who had on more than one occasion in the past been found in competition with him.

The Friulan, after many wanderings and much labour in North Italy, had settled in Venice in 1535, and there acquired an immense reputation by the grandeur and consummate ease with which he had carried out great mural decorations, such as the façade of Martin d'Anna's house on the Grand Canal, comprising in its scheme of decoration a Curtius on horse-back and a flying Mercury which according to Vasari became the talk of the town.[25] Here, at any rate, was a field in which even Titian himself, seeing that he had only at long intervals practised in fresco painting, could not hope to rival Pordenone. The Friulan, indeed, in this his special branch, stood entirely alone among the painters of North Italy.

The Council of Ten in June 1537 issued a decree recording that Titian had since 1516 been in possession of his senseria, or broker's patent, and its accompanying salary, on condition that he should paint "the canvas of the land fight on the side of the Hall of the Great Council looking out on the Grand Canal," but that he had drawn his salary without performing his promise. He was therefore called upon to refund all that he had received for the time during which he had done no work. This sharp reminder operated as it was intended to do. We see from Aretino's correspondence that in November 1537 Titian was busily engaged on the great canvas for the Doges' Palace. This tardy recognition of an old obligation did not prevent the Council from issuing an order in November 1538 directing Pordenone to paint a picture for the Sala del Gran Consiglio, to occupy the space next to that reserved for Titian's long-delayed battle-piece.

That this can never have been executed is clear, since Pordenone, on receipt of an urgent summons from Ercole II., Duke of Ferrara, departed from Venice in the month of December of the same year, and falling sick at Ferrara, died so suddenly as to give rise to the suspicion of foul play, which too easily sprang up in those days when ambition or private vengeance found ready to hand weapons so many and so convenient. Crowe and Cavalcaselle give good grounds for the assumption that, in order to save appearances, Titian was supposed—replacing and covering the battle-piece which already existed in the Great Hall—to be presenting the Battle of Spoleto in Umbria, whereas it was clear to all Venetians, from the costumes, the banners, and the landscape, that he meant to depict the Battle of Cadore fought in 1508. The latter was a Venetian victory and an Imperial defeat, the former a Papal defeat and an Imperial victory. The all-devouring fire of 1577 annihilated the Battle of Cadore with too many other works of capital importance in the history both of the primitive and the mature Venetian schools. We have nothing now to show what it may have been, save the print of Fontana, and the oil painting in the Venetian Gallery of the Uffizi, reproducing on a reduced scale part only of the big canvas. This last is of Venetian origin, and more or less contemporary, but it need hardly be pointed out that it is a copy from, not a sketch for, the picture.

To us who know the vast battle-piece only in the feeble echo of the print and the picture just now mentioned, it is a little difficult to account for the enthusiasm that it excited, and the prominent place accorded to it among the most famous of the Cadorine's works. Though the whole has abundant movement and passion, and the mise-en-scène is undoubtedly imposing, the combat is not raised above reality into the region of the higher and more representative truth by any element of tragic vastness and significance. Even though the Imperialists are armed more or less in the antique Roman fashion, to distinguish them from the Venetians, who appear in the accoutrements of their own day, it is still that minor and local combat the Battle of Cadore that we have before us, and not, above and beyond this battle, War, as some masters of the century, gifted with a higher power of evocation, might have shown it. Even as the fragment of Leonardo da Vinci's Battle of Anghiari survives in the free translation of Rubens's well-known drawing in the Louvre, we see how he has made out of the unimportant cavalry combat, yet without conventionality or undue transposition, a representation unequalled in art of the frenzy generated in man and beast by the clash of arms and the scent of blood. And Rubens, too, how incomparably in the Battle of the Amazons of the Pinakothek at Munich, he evokes the terrors, not only of one mortal encounter, but of War—the hideous din, the horror of man let loose and become beast once more, the pitiless yell of the victors, the despairing cry of the vanquished, the irremediable overthrow! It would, however, be foolhardy in those who can only guess at what the picture may have been to arrogate to themselves the right of sitting in judgment on Vasari and those contemporaries who, actually seeing, enthusiastically admired it. What excited their delight must surely have been Titian's magic power of brush as displayed in individual figures and episodes, such as that famous one of the knight armed by his page in the immediate foreground.

Into this period of our master's career there fit very well the two portraits in which he appears, painted by himself, on the confines of old age, vigorous and ardent still, fully conscious, moreover, though without affectation, of pre-eminent genius and supreme artistic rank. The portraits referred to are those very similar ones, both of them undoubtedly originals, which are respectively in the Berlin Gallery and the Painters' Gallery of the Uffizi. It is strange that there should exist no certain likeness of the master of Cadore done in youth or earlier manhood, if there be excepted the injured and more than doubtful production in the Imperial Gallery of Vienna, which has pretty generally been supposed to be an original auto-portrait belonging to this period. In the Uffizi and Berlin pictures Titian looks about sixty years old, but may be a little more or a little less. The latter is a half-length, showing him seated and gazing obliquely out of the picture with a majestic air, but also with something of combativeness and disquietude, an element, this last, which is traceable even in some of the earlier portraits, but not in the mythological poesie or any sacred work. More and more as we advance through the final period of old age do we find this element of disquietude and misgiving asserting itself in male portraiture, as, for instance, in the Maltese Knight of the Prado, the Dominican Monk of the Borghese, the Portrait of a Man with a Palm Branch of the Dresden Gallery. The atmosphere of sadness and foreboding enveloping man is traceable back to Giorgione; but with him it comes from the plenitude of inner life, from the gaze turned inwards upon the mystery of the human individuality rather than outwards upon the inevitable tragedies of the exterior life common to all. This same atmosphere of passionate contemplativeness enwraps, indeed, all that Giorgione did, and is the cause that he sees the world and himself lyrically, not dramatically; the flame of aspiration burning steadily at the heart's core and leaving the surface not indeed unruffled, but outwardly calm in its glow. Titian's is the more dramatic temperament in outward things, but also the more superficial. It must be remembered, too, that arriving rapidly at the maturity of his art, and painting all through the period of the full Renaissance, he was able with far less hindrance from technical limitations to express his conceptions to the full. His portraiture, however, especially his male portraiture, was and remained in its essence a splendid and full-blown development of the Giorgionesque ideal. It was grander, more accomplished, and for obvious reasons more satisfying, yet far less penetrating, less expressive of the inner fibre, whether of the painter or of his subject.

But to return to the portrait of Berlin. It is in parts unfinished, and therefore the more interesting as revealing something of the methods employed by the master in this period of absolute mastery, when his palette was as sober in its strength as it was rich and harmonious; when, as ever, execution was a way to an end, and therefore not to be vain-gloriously displayed merely for its own sake. The picture came, with very many other masterpieces of the Italian and Netherlandish schools, from the Solly collection, which formed the nucleus of the Berlin Gallery. The Uffizi portrait emerges noble still, in its semi-ruined state, from a haze of restoration and injury, which has not succeeded in destroying the exceptional fineness and sensitiveness of the modelling. Although the pose and treatment of the head are practically identical with that in the Berlin picture, the conception seems a less dramatic one. It includes, unless the writer has misread it, an element of greater mansuetude and a less perturbed reflectiveness.

The double portrait in the collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, styled Titian and Franceschini[26] has no pretensions whatever to be even discussed as a Titian. The figure of the Venetian senator designated as Franceschini is the better performance of the two; the lifeless head of Titian, which looks very like an afterthought, has been copied, without reference to the relation of the two figures the one to the other, from the Uffizi picture, or some portrait identical with it in character. A far finer likeness of Titian than any of these is the much later one, now in the Prado Gallery; but this it will be best to deal with in its proper chronological order.

We come now to one of the most popular of all Titian's great canvases based on a sacred subject, the Presentation in the Temple in the Accademia delle Belle Arti at Venice. This, as Vasari expressly states, was painted for the Scuola di S. Maria della Carità, that is, for the confraternity which owned the very building where now the Accademia displays its treasures. It is the magnificent scenic rendering of a subject lending itself easily to exterior pomp and display, not so easily to a more mystic and less obvious mode of conception. At the root of Titian's design lies in all probability the very similar picture on a comparatively small scale by Cima da Conegliano, now No. 63 in the Dresden Gallery, and this last may well have been inspired by Carpaccio's Presentation of the Virgin, now in the Brera at Milan.[27] The imposing canvases belonging to this particular period of Titian's activity, and this one in particular, with its splendid architectural framing, its wealth of life and movement, its richness and variety in type and costume, its fair prospect of Venetian landscape in the distance, must have largely contributed to form the transcendent decorative talent of Paolo Veronese. Only in the exquisitely fresh and beautiful figure of the childlike Virgin, who ascends the mighty flight of stone steps, clad all in shimmering blue, her head crowned with a halo of yellow light, does the artist prove that he has penetrated to the innermost significance of his subject. Here, at any rate, he touches the heart as well as feasts the eye. The thoughts of all who are familiar with Venetian art will involuntarily turn to Tintoretto's rendering of the same moving, yet in its symbolical character not naturally ultra-dramatic, scene. The younger master lends to it a significance so vast that he may be said to go as far beyond and above the requirements of the theme as Titian, with all his legitimate splendour and serene dignity, remains below it. With Tintoretto as interpreter we are made to see the beautiful episode as an event of the most tremendous import—one that must shake the earth to its centre. The reason of the onlooker may rebel against this portentous version, yet he is dominated all the same, is overwhelmed with something of the indefinable awe that has seized upon the bystanders who are witnesses of the scene.

But now to discuss a very curious point in connection with the actual state of Titian's important canvas. It has been very generally assumed—and Crowe and Cavalcaselle have set their seal on the assumption—that Titian painted his picture for a special place in the Albergo (now Accademia), and that this place is now architecturally as it was in Titian's time. Let them speak for themselves. "In this room (in the Albergo), which is contiguous to the modern hall in which Titian's Assunta is displayed, there were two doors for which allowance was made in Titian's canvas; twenty-five feet—the length of the wall—is now the length of the picture. When this vast canvas was removed from its place, the gaps of the doors were filled in with new linen, and painted up to the tone of the original...."

That the pieces of canvas to which reference is here made were new, and not Titian's original work from the brush, was of course well known to those who saw the work as it used to hang in the Accademia. Crowe and Cavalcaselle give indeed the name of a painter of this century who is responsible for them. Within the last three years the new and enterprising director of the Venice Academy, as part of a comprehensive scheme of rearrangement of the whole collection, caused these pieces of new canvas to be removed and then proceeded to replace the picture in the room for which it is believed to have been executed, fitting it into the space above the two doors just referred to. Many people have declared themselves delighted with the alteration, looking upon it as a tardy act of justice done to Titian, whose work, it is assumed, is now again seen just as he designed it for the Albergo. The writer must own that he has, from an examination of the canvas where it is now placed, or replaced, derived an absolutely contrary impression. First, is it conceivable that Titian in the heyday of his glory should have been asked to paint such a picture—not a mere mural decoration—for such a place? There is no instance of anything of the kind having been done with the canvases painted by Gentile Bellini, Carpaccio, Mansueti, and others for the various Scuole of Venice. There is no instance of a great decorative canvas by a sixteenth century master of the first rank,[28] other than a ceiling decoration, being degraded in the first instance to such a use. And then Vasari, who saw the picture in Venice, and correctly characterises it, would surely have noticed such an extraordinary peculiarity as the abnormal shape necessitated by the two doors. It is incredible that Titian, if so unpalatable a task had indeed been originally imposed upon him, should not have designed his canvas otherwise. The hole for the right door coming in the midst of the monumental steps is just possible, though not very probable. Not so that for the left door, which, according to the present arrangement, cuts the very vitals out of one of the main groups in the foreground. Is it not to insult one of the greatest masters of all time thus to assume that he would have designed what we now see? It is much more likely that Titian executed his Presentation in the first place in the normal shape, and that vandals of a later time, deciding to pierce the room in the Scuola in which the picture is now once more placed with one, or probably two, additional doors, partially sacrificed it to the structural requirements of the moment. Monstrous as such barbarism may appear, we have already seen, and shall again see later on, that it was by no means uncommon in those great ages of painting, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

When the untimely death of Pordenone, at the close of 1538, had extinguished the hopes of the Council that the grandiose facility of this master of monumental decoration might be made available for the purposes of the State, Titian having, as has been seen, made good his gravest default, was reinstated in his lucrative and by no means onerous office. He regained the senseria by decree of August 28, 1539. The potent d'Avalos, Marqués del Vasto, had in 1539 conferred upon Titian's eldest son Pomponio, the scapegrace and spendthrift that was to be, a canonry. Both to father and son the gift was in the future to be productive of more evil than good. At or about the same time he had commissioned of Titian a picture of himself haranguing his soldiers in the pompous Roman fashion; this was not, however, completed until 1541. Exhibited by d'Avalos to admiring crowds at Milan, it made a sensation for which there is absolutely nothing in the picture, as we now see it in the gallery of the Prado, to account; but then it would appear that it was irreparably injured in a fire which devastated the Alcazar of Madrid in 1621, and was afterwards extensively repainted. The Marquis and his son Francesco, both of them full-length figures, are placed on a low plinth, to the left, and from this point of vantage the Spanish leader addresses a company of foot-soldiers who with fine effect raise their halberds high into the air.[29] Among these last tradition places a portrait of Aretino, which is not now to be recognised with any certainty. Were the pedigree of the canvas a less well-authenticated one, one might be tempted to deny Titian's authorship altogether, so extraordinary are, apart from other considerations, the disproportions in the figure of the youth Francesco. Restoration must in this instance have amounted to entire repainting. Del Vasto appears more robust, more martial, and slightly younger than the armed leader in the Allegory of the Louvre. If this last picture is to be accepted as a semi-idealised presentment of the Spanish captain, it must, as has already been pointed out, have been painted nearer to the time of his death, which took place in 1546. The often-cited biographers of our master are clearly in error in their conclusion that the painting described in the collection of Charles I. as "done by Titian, the picture of the Marquis Guasto, containing five half-figures so big as the life, which the king bought out of an Almonedo," is identical with the large sketch made by Titian as a preparation for the Allocution of Madrid. This description, on the contrary, applies perfectly to the Allegory of the Louvre, which was, as we know, included in the collection of Charles, and subsequently found its way into that of Louis Quatorze.

It was in 1542 that Vasari, summoned to Venice at the suggestion of Aretino, paid his first visit to the city of the Lagoons in order to paint the scenery and apparato in connection with a carnival performance, which included the representation of his fellow-townsman's Talanta.[30] It was on this occasion, no doubt, that Sansovino, in agreement with Titian, obtained for the Florentine the commission to paint the ceilings of Santo Spirito in Isola—a commission which was afterwards, as a consequence of his departure, undertaken and performed by Titian himself, with whose grandiose canvases we shall have to deal a little later on. In weighing the value of Vasari's testimony with reference to the works of Vecellio and other Venetian painters more or less of his own time, it should be borne in mind that he paid two successive visits to Venice, enjoying there the company of the great painter and the most eminent artists of the day, and that on the occasion of Titian's memorable visit to Rome he was his close friend, cicerone, and companion. Allowing for the Aretine biographer's well-known inaccuracies in matters of detail and for his royal disregard of chronological order—faults for which it is manifestly absurd to blame him over-severely—it would be unwise lightly to disregard or overrule his testimony with regard to matters which he may have learned from the lips of Titian himself and his immediate entourage.

To the year 1542 belongs, as the authentic signature and date on the picture affirm, that celebrated portrait, The Daughter of Roberto Strozzi, once in the splendid palace of the family at Florence, but now, with some other priceless treasures having the same origin, in the Berlin Museum. Technically, the picture is one of the most brilliant, one of the most subtly exquisite, among the works of the great Cadorine's maturity. It well serves to show what Titian's ideal of colour was at this time. The canvas is all silvery gleam, all splendour and sober strength of colour—yet not of colours. These in all their plentitude and richness, as in the crimson drapery and the distant landscape, are duly subordinated to the main effect; they but set off discreetly the figure of the child, dressed all in white satin with hair of reddish gold, and contribute without fanfare to the fine and harmonious balance of the whole. Here, as elsewhere, more particularly in the work of Titian's maturity, one does not in the first place pause to pick out this or the other tint, this or the other combination of colours as particularly exquisite; and that is what one is so easily led to do in the contemplation of the Bonifazi and of Paolo Veronese.

As the portrait of a child, though in conception it reveals a marked progress towards the intimité of later times, the Berlin picture lacks something of charm and that quality which, for want of a better word, must be called loveableness. Or is it perhaps that the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries have spoilt us in this respect? For it is only in these latter days that to the child, in deliberate and avowed portraiture, is allowed that freakishness, that natural espièglerie and freedom from artificial control which has its climax in the unapproached portraits of Sir Joshua Reynolds. This is the more curious when it is remembered how tenderly, with what observant and sympathetic truth the relation of child to mother, of child to child, was noted in the innumerable "Madonnas" and "Holy Families" of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; how both the Italians, and following them the Netherlanders, relieved the severity of their sacred works by the delightful roguishness, the romping impudence of their little angels, their putti.